Abstract

Many of the cognitive deficits of normal aging (forgetfulness, distractibility, inflexibility, and impaired executive functions) involve prefrontal cortical (PFC) dysfunction1–4. The PFC guides behavior and thought using working memory5, essential functions in the Information Age. Many PFC neurons hold information in working memory through excitatory networks that can maintain persistent neuronal firing in the absence of external stimulation6. This fragile process is highly dependent on the neurochemical environment7. For example, elevated cAMP signaling reduces persistent firing by opening HCN and KCNQ potassium channels8,9. It is not known if molecular changes associated with normal aging alter the physiological properties of PFC neurons during working memory, as there have been no in vivo recordings from PFC neurons of aged monkeys. Here we characterize the first recordings of this kind, revealing a marked loss of PFC persistent firing with advancing age that can be rescued by restoring an optimal neurochemical environment. Recordings showed an age-related decline in the firing rate of DELAY neurons, while the firing of CUE neurons remained unchanged with age. The memory-related firing of aged DELAY neurons was partially restored to more youthful levels by inhibiting cAMP signaling, or by blocking HCN or KCNQ channels. These findings reveal the cellular basis of age-related cognitive decline in dorsolateral PFC, and demonstrate that physiological integrity can be rescued by addressing the molecular needs of PFC circuits.

Keywords: prefrontal cortex, working memory, aging, cAMP signaling, HCN channels, KCNQ channels, α2A adrenoceptors

Our society is rapidly aging, with the number of seniors expected to double by 2050 (US Census: http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/elderpop.html). At the same time, the Information Age requires increasing organizational skills to deal with even basic needs such as medical care and paying bills. However, executive and working memory functions decline early in the normal aging process10–13, beginning in middle age14,15. Thus, cognitive changes with advancing age may be costly, forcing retirement from demanding careers and jeopardizing the ability to live independently in an increasingly complex society. Aging monkeys provide an ideal model to reveal the neurobiology of normal aging, as they have a highly developed PFC, but are not subject to age-related dementias16. Thus, one can be certain that cognitive changes are the result of normal aging and not incipient Alzheimer’s Disease. Like humans, monkeys begin to develop deficits in executive function as early as middle age17. Both aged monkeys18,19 and humans3,20 are impaired on working memory tasks that require constant updating of the contents of memory (Supplementary Information), bringing to mind information from longer-term stores (e.g. where did I leave my car keys this time?), or keeping in mind a recent event (e.g. remembering a new phone number).

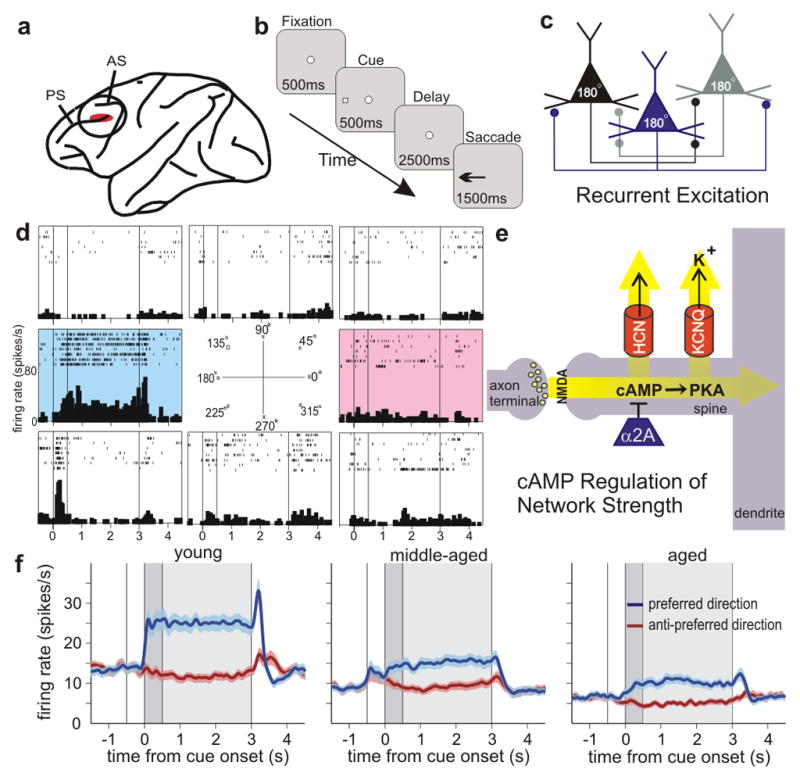

In primates, spatial working memory depends upon the highly evolved dorsolateral PFC6 (Fig. 1a). Spatial working memory performance (Fig. 1b) relies on networks of pyramidal neurons that interconnect at dendritic spines (Fig. 1c), and excite each other to keep information “in mind”, i.e. generating persistent spiking activity over a delay period in a working memory task6 (Fig. 1d). This ability to maintain information that is no longer in the environment is a fundamental process needed for abstract thought and flexible responding6. Intracellular signaling pathways modulate the physiological strength of these recurrent, excitatory PFC network connections9. Recent data show that increased cAMP signaling weakens network connectivity by opening potassium channels, while inhibiting cAMP signaling and/or closing these channels strengthens connectivity and cognitive ability9 (Fig. 1e). Specifically, cAMP signaling appears to weaken persistent firing and impair working memory by increasing the open state of HCN (Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide gated) channels that are localized on spines where networks interconnect8. Recent data suggest that HCN channels may also gate synaptic inputs through interactions with KCNQ channels, whose open state is increased by cAMP activating protein kinase A (PKA)21. studies suggest that cAMP signaling is disinhibited in the aged PFC22. Noradrenergic α2A receptor inhibition of cAMP may be reduced from loss of α2A receptors in the aged PFC23, and decreased excitation of noradrenergic neurons24.

Figure 1.

Age-related changes in the PFC networks that subserve working memory. a, The region of the DLPFC most needed for spatial working memory and the site of recordings. PS=principal sulcus; AS=arcuate sulcus. b, The oculomotor delayed response (ODR) spatial working memory task. The monkey fixates on the central stimulus and maintains fixation for the duration of the trial. A cue is briefly presented in one of eight locations, followed by a delay period (2.5s) in which no spatial information is present. At the end of the delay period, the fixation spot disappears, and the monkey makes an eye movement (saccade) to the remembered location for juice reward. The cue position randomly changes on subsequent trials. c, A diagram of the recurrent excitatory networks subserving working memory. Pyramidal cells with similar spatial tuning excite each other to maintain persistent firing across the delay period6. These networks are concentrated in deep layer III 6. Spatial tuning is enhanced by GABAergic lateral inhibition (not shown). d, An example of a DLPFC DELAY neuron with spatially-tuned, persistent firing during the delay period. This neuron shows increased firing for the cue, delay and response for the neuron’s preferred direction (highlighted in blue), but not for nonpreferred directions (white backgrounds). The anti-preferred direction opposite to the neuron’s preferred direction is shown in red; note that subsequent figures show only the preferred and anti-preferred directions for the sake of brevity. e, Pyramidal cells synapse on spines where cAMP-PKA signaling regulates the open state of HCN and KCNQ channels, and thus modulates the strength of network connections9.. f, Population average activity for the DLPFC DELAY neurons recorded in each age group (102, 101, and 70 neurons for young, middle-aged and old monkeys, respectively). Colors indicate the activity during the trials in which the cue was presented in the neuron’s preferred (blue) and anti-preferred (red) directions; the darker gray background refers to the cue period; the lighter gray background to the delay period.

There have been few electrophysiological recordings from aged PFC neurons due to the demanding nature of this procedure. Recordings from rat orbital PFC found reduced flexibility in aged neurons25. However, there have been no in vivo recordings from the aged dorsolateral PFC, even though behavioral data suggest that this region is particularly vulnerable to normal aging. In vitro recordings from dorsolateral PFC neurons found relatively subtle changes in excitability with advancing age26, but their consequence to executive function must be observed in a cognitively-engaged circuit. The current study performed the very first physiological characterization of PFC neuronal response during a working memory task in young adult, middle-aged, and aged monkeys.

Monkeys (macaca mulatta, n=6) were trained to perform a spatial working memory task in which they must remember a spatial location over a brief delay period; the spatial location changes randomly on each trial (Fig. 1A). Two animals were young adults (7 and 9 year old males), two were middle-aged (12 and 13 year old males), and two were aged (17 year old male, 21 year old female). Short delays (2.5s) were used in all age groups to ensure similar performance (>85% percent correct) across age groups. Neurons (n=301) were recorded from area 46, the dorsolateral PFC subregion most needed for visuospatial working memory (Fig. 1a). Neurons were characterized based on task-related firing as responsive during a) the visuospatial cue period, b) the delay period when the spatial position was being remembered, and/or c) the motor response period. Some neurons fired only during cue presentation (CUE cells, n=28), while most neurons fired during the delay period as well as to the cue and/or response periods (DELAY cells, n=273). Persistent firing during the delay period is of particular interest, as it is required for working memory6. Many PFC DELAY neurons elevated their activity during the memory of one spatial location (its preferred direction, shown in blue), but not other locations (the “anti-preferred” direction 180° away from the preferred direction is shown in red; Fig. 1d).

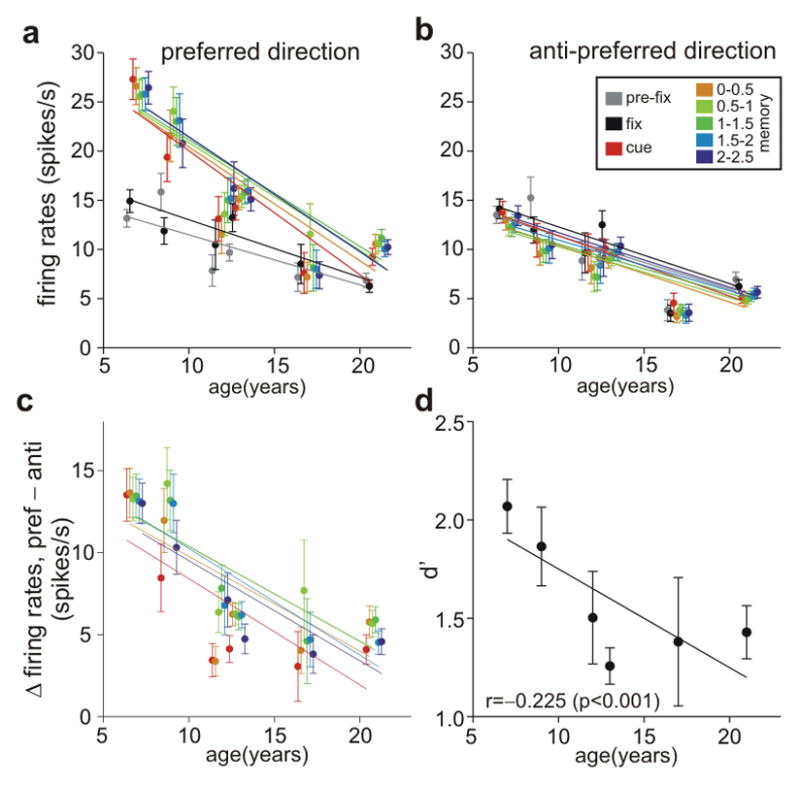

The firing of DELAY cells was markedly reduced with advancing age (Fig. 1f, Fig. 2). Figure 1f portrays the differences in firing rates across the population of DELAY neurons in young, middle-aged and aged animals (individual examples of DELAY neurons in young, middle-aged and aged monkeys are in Supplementary Fig. 1). There was a significant decline in the spontaneous firing rate of DELAY cells, as well as a marked decline in task-related firing. Figure 2 shows a steep decline in the firing rates of DELAY cells across the age span (t-test on age variable in regression analysis, p<10−4 for all epochs), with older animals showing a restricted range of lower firing rates (Supplementary Fig. 2). This age-related activity decline persisted throughout the 2.5-s delay period (without main effect of epoch (0.5 s) or age × epoch interaction in repeated measures ANOVA, p>0.25). Additional control analyses showed that age-related decline in the firing rate of DELAY cells is not likely due to a sampling bias during the recording experiment (see Supplementary Information). The age-related decline in firing rate was particularly prominent during the cue and delay periods for the neuron’s preferred direction (Fig. 2a); the decline in firing for the anti-preferred direction (Fig. 2b) or before target onset (Fig. 2a) was less pronounced. Consequently, the difference in delay-related firing for the neuron’s preferred direction vs. its anti-preferred direction eroded with increasing age (t-test, p<10−5, for cue period and every 0.5s epoch in the delay period; Fig. 2c), largely due to reduced firing for the neuron’s preferred direction (Fig. 2a). This led to a reduction in d′ with advancing age (t-test on age vs. d′ correlation coefficient, p<0.0001), i.e. a reduced ability to distinguish the preferred from anti-preferred directions during the delay period when spatial information was held in working memory (Fig. 2d). These results are consistent with studies showing impairment in spatial working memory in aged monkeys at relatively short (e.g. 5s) delays18, and single-unit data as well as neural circuit modeling suggest that inadequate PFC recurrent network firing underlies the deficits in PFC cognitive function observed in aging monkeys and humans (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4; Supplementary Information).

Figure 2.

Age-dependent decline in the spatially-tuned, persistent firing of DLPFC DELAY neurons. a, Marked reduction of DLPFC DELAY activity for the neurons’ preferred direction with advancing age. Activity of individual neurons of each animal was averaged separately for the last 0.5 s during the intertrial interval (pre-fix, gray), the fixation period (fix, black), the cue period (cue, red), and the delay period for the neuron’s preferred direction. Firing during the delay period is represented in a successive series of 0.5-s intervals (color-coded yellow through blue). Lines were obtained using linear regression. b, Firing rates during the delay period for the anti-preferred direction of the same neurons shown in A. There was a significant age-related decline in all epochs, but it was less prominent than the decline in firing for the preferred direction during the delay period. Color-coding for each 0.5s interval as in Fig. A. c, Age-related decline in spatial tuning, whereby the difference between firing for the preferred vs. anti-preferred directions during the delay period declines with advancing age. Color-coding as in Fig. a. d, Age-related decline in d′, i.e. the ability to distinguish preferred from anti-preferred spatial directions based on firing rate patterns during the entire delay period.

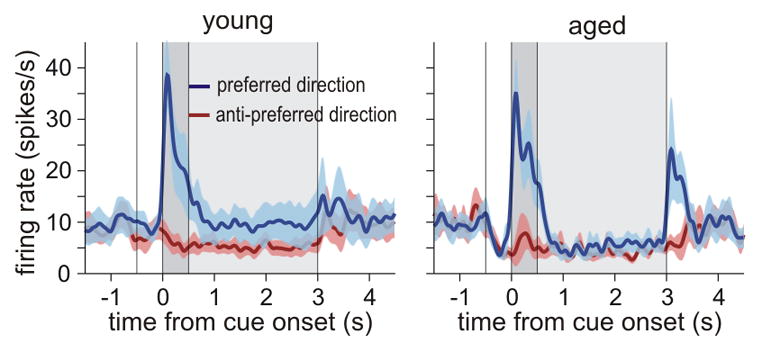

In contrast to DELAY neurons that showed prominent decline in firing with advancing age, there were no age-related changes in firing rates of PFC CUE cells that responded specifically to the spatial cue (Fig. 3). The average firing rate of these neurons for the preferred direction during the cue period was 26.7±4.4 spikes/s in young monkeys (n=12 neurons), and 25.3±3.7 spikes/s in old monkeys (11 neurons; t-test, p>0.8; significant age × cell type interaction in 2-way ANOVA, p<0.05). These data suggest that reductions in memory-related firing rate do not arise from generalized changes with advancing age affecting all neurons, but rather, are especially evident in recurrent circuits that must maintain firing in the absence of “bottom-up” sensory stimulation.

Figure 3.

Firing rates of DLPFC CUE cells remain stable in aged monkeys. The average firing rates of CUE cells in young monkeys (left graph; 10 neurons from a 7-y old and 2 neurons from a 9-y old monkey), did not differ from the firing rate in the oldest monkey (right graph; 11 neurons from a 21-y old monkey), or from the firing rate averaged for both middle-aged (5 neurons from 13-y old monkey, not shown separately) and old monkeys (t-test, p>0.7). CUE cells may receive direct, “bottom-up” excitation from parietal association cortex6, which may be less vulnerable to subtle molecular changes with advancing age. A subset of CUE cells recorded in the aged monkey displayed high firing rates during the Response period.

What changes in the aging brain contribute to reduced firing during the delay period? There are many brain alterations associated with advancing age27, including decreased PFC gray matter volume28, focal changes in white matter29, and dendritic spine loss30, all of which correlate with cognitive decline. Importantly, spine loss is especially prominent in layer III- the layer where the recurrent excitatory networks reside- and thin-type spines are the most vulnerable in the aged PFC30. Immunoelectron microscopy indicates that thin spines have the greatest concentration of cAMP-HCN channel signaling proteins, suggesting that disinhibition of cAMP signaling with advancing age may weaken thin spines in particular9. Thus, we tested whether inhibition of cAMP signaling in the PFC could partially restore the working memory-related firing of aged neurons, or whether reductions in firing were irreversible due to immutable architectural changes in the aged brain. Drugs were applied near the recorded neurons using iontophoresis, whereby a small electrical current was applied to extrude charged molecules from glass pipettes attached to the recording electrode. Only a minute amount of drug was released, sufficient to alter the firing of nearby neurons, without altering behavioral performance.

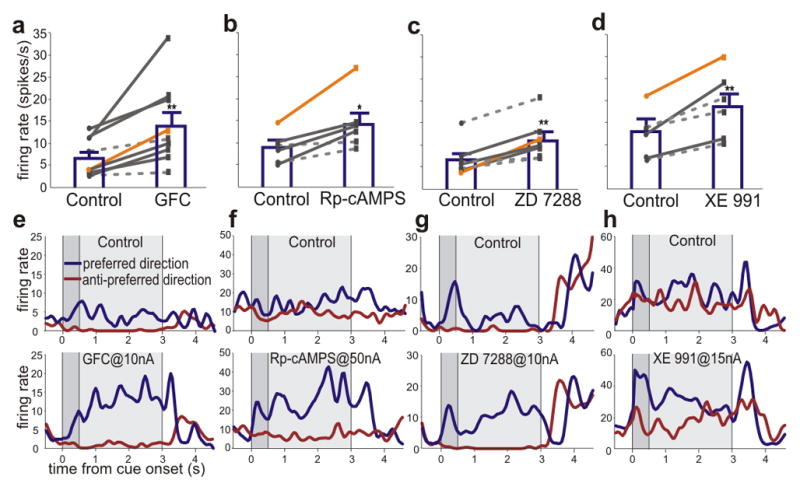

Agents that inhibit cAMP signaling or block HCN or KCNQ channels restored persistent firing during the delay period of the working memory task (Fig. 4). For example, iontophoresis of the α2A agonist, guanfacine (Fig. 4a, e), or the cAMP-PKA inhibitor, Rp-cAMPS (Fig. 4b, f), significantly increased firing during the delay period on trials when the cue had appeared at the neuron’s preferred direction. In contrast, the PDE4 inhibitor, etazolate- which increases cAMP signaling- further decreased neuronal firing in aged neurons (p<0.001; Supplementary Fig. 5). We also tested whether blockade of HCN or KCNQ channels could restore firing, given that cAMP-PKA signaling increases the open state of these ion channels. As shown in Figures 4c and g, a low dose of the HCN channel blocker, ZD7288 significantly enhanced the delay-related firing rates of neurons in aged monkeys. KCNQ channels were also of interest, as in vitro physiological characterizations of PFC neurons in aged primate have found increases in the slow afterhyperpolarization (sAHP), which is mediated in part by KCNQ channels26. As shown in Figures 4d and h, blockade of KCNQ channels with XE991 increased delay-related firing in aged PFC neurons. Thus, agents that reduced cAMP opening of HCN or KCNQ channels all restored firing rates to levels resembling those observed in younger monkeys. These findings are consistent with behavioral data showing that guanfacine and Rp-cAMPS can enhance working memory performance in aged animals when administered systemically (guanfacine) or directly into the rat PFC (guanfacine or Rp-cAMPS)22 (see Supplementary Information). Based on these data, guanfacine is currently being tested in elderly humans with PFC cognitive deficits (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00935493).

Figure 4.

Iontophoresis of compounds that inhibit cAMP-PKA signaling, or block HCN or KCNQ channel signaling, strengthens delay-related firing in aged PFC DELAY neurons. a–d,. A summary of the results showing a significant increase in population-average firing rate for the neuron’s preferred direction compared to control conditions (paired t-test, p<0.01 for a, c and d, and p<0.05 for b) following iontophoresis of: the α2A adrenergic agonist guanfacine applied at 10nA (GFC; a, significant effects in 7 out of 9 neurons, t-test, p<0.05, indicated by solid lines); the cAMP inhibitor Rp-cAMPS at 50 nA (b, significant in 4 out of 6 neurons); the HCN channel blocker, ZD7288 at 15 nA (c, significant in 4 out of 7 neurons); and the KCNQ channel blocker XE991 at 15 nA (d, significant in 3 out of 6 neurons). In all cases, significant effects were found more frequently than expected by chance (binomial test, p<0.005). The orange lines represent the individual neurons shown in e-h. e–h, Individual examples of neurons under control conditions (top) firing to their preferred (blue trace) or anti-preferred (red trace) directions, compared to their firing patterns following iontophoresis of guanfacine (e), Rp-cAMPS (f), ZD7288 (g) or XE991 (h). The orange lines in a-d indicate the individual neurons shown in e-h. Error bars are s.e.m. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 significant difference between drug vs. control for the neuron’s preferred direction.

In summary, the current study revealed a physiological basis for age-related working memory decline in the primate brain, with reduction of memory-related firing beginning in middle age and worsening with advancing age. This marked change in network physiology may render higher cortical circuits especially vulnerable to neurodegenerative processes such as Alzheimer’s Disease. However, these studies also uncovered more hopeful data showing that restitution of the proper neurochemical environment can partially restore physiological integrity. These data establish that cognitive changes with advancing age are malleable, and that there is potential to restore at least some cognitive abilities in the elderly. Maintaining strong PFC physiology into advanced age will be an important advantage in an increasingly complex, aging society.

Methods summary

All experiments were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Yale IACUC.

Behavioral training

Monkeys were trained on the oculomotor delayed response (ODR) task (Fig. 1b) as reported elsewhere8, with special care to minimize all stress. The aged monkeys took longer to learn the task, rested more frequently than young monkeys during the testing sessions, and performed fewer trials each day than younger animals. A brief delay period (2.5s) was chosen to ensure that all monkeys in the study performed above 85% correct during training, and could maintain high levels of performance during the study (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Physiology and iontophoresis

Single unit recordings were made from the dorsolateral PFC surrounding the caudal portion of the principal sulcus (Fig. 1a). Details of the recording procedures and iontophoresis methods can be found in Wang et al, 20078. Single neuron activity was readily isolated (Supplementary Fig 7). Denoting the average activity during the 0.5-s cue period and that during the 2.5-s delay period during the trials in preferred directions as C and D, neurons were classified as CUE cells, when the ratio D/C was >0.5, and as DELAY cells otherwise. Statistical analyses, including ANOVA and regression analyses were performed using Matlab (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). The effect of age on firing rate during a series of 0.5-s epoch was tested using a regression model, and its statistical significance with a t-test.

Methods

Oculomotor Delayed Response Task

Studies were performed on four adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) trained on the spatial oculomotor delayed response (ODR) task as previously described (Williams et al., 2002). This task requires the monkey to make a memory-guided saccade to a remembered visuo-spatial target. Each trial began when the subject fixated at the central spot for 0.5 sec (fixation period). Subsequently, a cue was illuminated for 0.5 sec at one of eight peripheral targets (cue period). After the cue was extinguished, a 2.5-sec delay period followed. During the cue and delay periods, the monkey was required to maintain central fixation. At the end of the delay, the fixation spot was extinguished, instructing the monkey to make a memory-guided saccade to the previously cued location (saccade period). The monkey was rewarded with fruit juice immediately after every successful response. The position of the stimulus was randomized over trials such that it had to be remembered on a trial-by-trial basis. The subject’s eye position was monitored with the ISCAN Eye Movement Monitoring System (ISCAN, Burlington, MA), and the ODR task was generated by the TEMPO real-time system (Reflective Computing, St. Louis, MO).

Recording Locus

Prior to recording, the animal underwent a magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan to obtain exact anatomical co-ordinates of brain structures, which guided placement of the chronic recording chambers. MRI-compatible materials were used for the implant so that the position of the recording chambers could be confirmed by MRI after implantation. The site of recordings in the present study were located in an area ranging from 0–5 mm anterior to the caudal end of the principal sulcus and −2-2mm medial to the principal sulcus.

Pharmacology, physiology and data acquisition

Guanfacine, XE991 and ZD7288 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO) and etazolate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were dissolved at 0.01M in triple-distilled water (adjusted with HCl to pH 3.5–4.0). Rp-cAMP (Sigma) was dissolved at 0.01M in triple-distilled water (adjusted with NaOH to pH 9).

Iontophoretic electrodes were constructed with a 20 μm pitch carbon fiber (ELSI, San Diego, CA) inserted in the central barrel of a seven-barrel non-filamented capillary glass (Friedrich and Dimmock, Millville, NJ). The assembly was pulled using a multipipette electrode puller (MicroData Instrument, Inc, NJ) and the tip was beveled to obtain the finished electrode. Finished electrodes had impedances of 0.3–1.0 MΩ (at 1kHz) and tip sizes of 30–40 μm. The outer barrels of the electrode were then filled with 3 drug solutions (two consecutive barrels each) and the solutions were pushed to the tip of the electrode using compressed air. A Neurophore BH2 iontophoretic system (Medical Systems Corp., Greenvale, NY) was used to control of the delivery of the drugs. The drug was ejected at currents that varied from 5–50 nA. Retaining currents of −3 to −5 nA were used in a cycled manner (1sec on, 1 sec off) when not applying drugs. Drug ejection did not create noise in the recording, and there was no systematic change in either spike amplitude or time course at any ejection current.

The electrode was mounted on a MO-95 micromanipulator (Narishige, East Meadow, NY) in a 25-gauge stainless steel guide tube. The dura was punctured using the guide tube to facilitate access of the electrode to cortex. Extra-cellular voltage was amplified using a AC/DC differential amplifier (A–M systems; Model 3000) and band-pass filtered (180Hz–6Khz, 20dB gain, 4-pole Butterworth; Kron-Hite, Avon, MA). Signals were digitized (20.83kHz, micro 1401, Cambridge Electronics Design, Cambridge, UK) and acquired using the Spike2 software (CED, Cambridge, UK). Neural activity was analyzed using waveform sorting by a template-matching algorithm, which made it possible to isolate more than one unit at the same recording site. Post-stimulus time histograms and rastergrams were constructed online to determine the relationship of unit activity to the task. Unit activity was measured in spikes per second. If the rastergrams displayed task-related activity, the units were recorded further and pharmacological testing was performed.

Data were first collected from the cell under a control condition in which at least eight trials at each of 8 cue locations were obtained. Upon establishing the stability of the cells’ activity, this control condition was followed by the drug application. Dose-dependent effects of the drug were tested in two or more consecutive conditions. Drugs were continuously applied at a relevant current throughout a given condition. Each condition had ~ 8 (typically 10 or more) trials at each location for statistical analyses of effects.

Data analysis

For purposes of data analysis, each trial in the ODR task was divided into four epochs – Fixation, Cue, Delay and Response (Saccade). The Fixation epoch lasted for 0.5 sec. The Cue epoch lasted for 0.5 sec and corresponds to the stimulus presentation phase of the task. Delay lasted for 2.5 sec and reflects the mnemonic component of the task. The Response phase started immediately after the Delay epoch and lasted ~1.5 sec.

Two-way analysis of variance, ANOVA, was used to examine the spatial tuned task-related activity with regard to: (1) different periods of the task (cue, delay, response vs. fixation) and (2) different cue locations. One-way ANOVAs were employed to assess the effect of the drug application on cells displaying delay-related activity. Statistical analyses, including ANOVA and regression analyses were performed using Matlab (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). The effect of age on firing rate during a series of 0.5-s epoch was tested using a regression model, and its statistical significance with a t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by PHS grant PO1AG030004 from the National Institute on Aging. The authors would like to thank Jessica Thomas, Lisa Ciavarella, Sam Johnson, Benny Brunson and Marianne Horn for their invaluable assistance in making this work possible.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information: A single pdf file that contains: 7 Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Data, Supplementary Discussion, and Supplementary References (cited in the Supplementary Discussion)

Author contributions- Drs. M. and X.-J. Wang, Mazer, Lee and Arnsten designed the experiments. Dr. M. Wang carried out all the physiology experiments, with the help of Dr. Yang, Ms. Gamo, Ms. Jin and Dr. Mazer. Data analyses were performed by Drs. M. Wang, Lee, Mazer and Laubach. Computational modeling was performed by Dr. X.-J. Wang. All authors participated in the writing of the paper.

Financial disclosure- Dr. Arnsten and Yale University receive royalties from Shire Pharmaceuticals from the sales of extended release guanfacine (Intuniv™) for the treatment of pediatric ADHD and related disorders (royalties are not received for sales of immediate release guanfacine which is approved for use in adults). Dr. Arnsten consults and engages in teaching for Shire, and receives research funding from Shire for the study of catecholamine mechanisms in prefrontal cortex.

References

- 1.West RL. An application of prefrontal cortex function theory to cognitive aging. Psychol Bull. 1996;120:272–292. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabeza R, Anderson ND, Houle S, Mangels JA, Nyberg L. Age-related differences in neural activity during item and temporal-order memory retrieval: a positron emission tomography study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:197–206. doi: 10.1162/089892900561832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gazzaley A, Cooney JW, Rissman J, D’Esposito M. Top-down suppression deficit underlies working memory impairment in normal aging. Nat Neurosci. 2005:1298–1300. doi: 10.1038/nn1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prakash RS, et al. Age-related differences in the involvement of the prefrontal cortex in attentional control. Brain Cogn. 2009;71:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman-Rakic PS. In: Handbook of Physiology, The Nervous System, Higher Functions of the Brain. Plum F, editor. V. American Physiological Society; 1987. pp. 373–417. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman-Rakic PS. Cellular basis of working memory. Neuron. 1995;14:477–485. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins TW, Arnsten AF. The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: monoaminergic modulation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:267–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, et al. α2A-adrenoceptor stimulation strengthens working memory networks by inhibiting cAMP-HCN channel signaling in prefrontal cortex. Cell. 2007;129:397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnsten AFT, Paspalas CD, Gamo NJYY, Wang M. Dynamic Network Connectivity: A new form of neuroplasticity. Trends Cog Sci. 2010;14:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowles RP, Salthouse TA. Assessing the age-related effects of proactive interference on working memory tasks using the Rasch model. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:608–615. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royall DR, Palmer R, Chiodo LK, Polk MJ. Normal rates of cognitive change in successful aging: the freedom house study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11:899–909. doi: 10.1017/s135561770505109x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke SN, Barnes CA. Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:30–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappell KA, Gmeindl L, Reuter-Lorenz PA. Age differences in prefontal recruitment during verbal working memory maintenance depend on memory load. Cortex. 2010;46:462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis HP, et al. Lexical priming deficits as a function of age. Behav Neurosci. 1990;104:286–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bucur B, Madden DJ. Effects of adult age and blood pressure on executive function and speed of processing. Exp Aging Res. 2010;36:153–168. doi: 10.1080/03610731003613482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sisodia SS, Martin LJ, Walker LC, Borchelt DR, Price DL. Cellular and molecular biology of Alzheimer’s disease and animal models. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 1995;5:59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore TL, Killiany RJ, Herndon JG, Rosene DL, Moss MB. Executive system dysfunction occurs as early as middle-age in the rhesus monkey. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1484–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rapp PR, Amaral DG. Evidence for task-dependent memory dysfunction in the aged monkey. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3568–3576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03568.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herndon JG, Moss MB, Rosene DL, Killiany RJ. Patterns of cognitive decline in aged rhesus monkeys. Behavioural Brain Research. 1997;87:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rypma B, D’Esposito M. Isolating the neural mechanisms of age-related changes in human working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2000:509–515. doi: 10.1038/74889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George MS, Abbott LF, Siegelbaum SA. Hyperpolarization-activated HCN channels inhibit subthreshold EPSPs through voltage-dependent interacations with M-type K+ channels. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nn.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramos B, et al. Dysregulation of protein kinase A signaling in the aged prefrontal cortex: New strategy for treating age-related cognitive decline. Neuron. 2003;40:835–845. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00694-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore TL, et al. Cognitive impairment in aged rhesus monkeys associated with monoamine receptors in the prefrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 2005;160:208–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downs JL, et al. Orexin neuronal changes in the locus coeruleus of the aging rhesus macaque. Neurobiol Aging. 2006 Jul 24; doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.025. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenbaum G, Setlow B, Saddoris MP, Gallagher M. Encoding changes in orbitofrontal cortex in reversal-impaired aged rats. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1509–1517. doi: 10.1152/jn.01052.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luebke JI, Chang YM. Effects of aging on the electrophysiological properties of layer 5 pyramidal cells in the monkey prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2007;150:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luebke J, Barbas H, Peters A. Effects of normal aging on prefrontal area 46 in the rhesus monkey. Brain Res Rev. 2010;62:212–232. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander GE, et al. Age-related regional network of magnetic resonance imaging gray matter in the rhesus macaque. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2710–2718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1852-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters A, et al. Neurobiological bases of age-related cognitive decline in the rhesus monkey. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:861–874. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumitriu D, et al. Selective changes in thin spine density and morphology in monkey prefrontal cortex correlate with aging-related cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7507–7515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6410-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.