Abstract

Background

Unlike Asian non-human primates, chronically SIV-infected African non-human primates (NHP) display a non-pathogenic disease course. The different outcomes may be related to the development of an SIV-mediated breach of the intestinal mucosa in the Asian species that is absent in the African animals.

Methods

To examine possible mechanisms that could lead to the gut breach, we determined whether the colonic lamina propria (LP) of SIV-naïve Asian monkeys contained more granzyme B (GrB) producing CD4 T-cells than did that of the African species. GrB is a serine protease that may disrupt mucosal integrity by damaging tight junction proteins.

Results

We found that the colonic LP of Asian NHP contain more CD4+/GrB+ cells than African NHP. We also observed reduced CD4 expression on LP T-cells in African green monkeys.

Conclusion

Both phenotypic differences could protect against SIV-mediated damage to the intestinal mucosa and could lead to future therapies in HIV+ humans.

Keywords: Immune activation, microbial translocation, colon, tight junctions, mucosal epithelium

INTRODUCTION

Experimental SIV infection of non-natural Asian hosts including rhesus macaques (RM; Macaca mulatta) and pigtail macaques (PM; Macaca nemestrina) results in severe depletion of CD4 T cells, chronic immune activation, and eventual collapse of the immune system (simian AIDS) [2, 4, 10, 16, 26, 27]. In sharp contrast, SIV infection of natural (non-pathogenic) African hosts such as African green monkeys (AGM; Chlorocebus sabeus) and sooty mangabeys (SM; Cercocebus atys) rarely progresses to simian AIDS [6, 13, 20, 26, 27]. Unlike RM and PM, immune responses mounted by non-pathogenic species against SIV are more controlled and transient, lasting a few weeks before returning to baseline levels [8, 10, 26, 27]. While the precise mechanisms responsible for the differences in the magnitude and duration of immune activation between non-pathogenic and pathogenic SIV hosts is not completely understood, a role for intestinal breach that contributes to bacterial translocation and chronic immune activation has received considerable attention [3, 9, 10, 12, 14, 20, 22]. This phenomenon does not occur following SIV infection of either AGM or SM [3, 10, 17, 20]. It has been observed that mRNA levels of occludin, a tight junction (TJ) protein, isolated from rectal biopsies were significantly reduced during both acute and chronic SIV infection in RM, but not SM [17]. Further support of the link between microbial translocation and chronic immune activation in the context of long-term SIV infection can be found in a recent study demonstrating that chronically SIV-infected AGM injected with exogenous LPS showed significant increases in immune activation, viral replication, and CD4 T cell depletion [19]. Why neither AGM nor SM experiences this “gut breach” following SIV infection is one of the issues that is fundamental to understanding SIV pathogenesis.

One possible mechanism of the gut breach is that infection of memory CD4 T cells in the intestinal LP induces activation and subsequent release of mediators into the microenvironment that may disrupt gap junction proteins between mucosal epithelial cells. Activated memory CD4 T cells, which are selectively infected by SIV in the LP, can secrete cytotoxic products including granzyme B (GrB), a serine protease typically associated with CD8 and NK cell directed apoptosis of target cells [24, 30, 31]. A recent study using an in vitro model of cancer metastasis observed that GrB secreted from human urothelial carcinoma cells could disrupt the extracellular matrix (ECM) protein vitronectin in healthy tissue, thereby promoting carcinoma invasion [7]. Furthermore, GrB has been implicated in the disruption of the TJ proteins, Occludin and Zona Occludin-1, in spinal cord homogenates from mice suffering experimental autoimmune encephomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of multiple sclerosis [11]. Thus, we hypothesized that if GrB is an important mediator of the gut breach observed during SIV-primary infection in RM and PM, these two species that develop SIV pathogenesis may have more GrB producing intestinal CD4 T cells in the uninfected state than would AGM and SM, two species that do not develop SIV pathogenesis. In the study described here, we observed that the colonic LP of uninfected RM and PM contain significantly higher proportions of CD4+/GrB+ cells than do the non-pathogenic species, AGM and SM.

METHODS

Collection of healthy tissue

Non-human primate tissue samples were obtained from the Washington National Primate Research Center (five PM), the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (five SM), and the New England Regional Primate Research Center (four AGM and four RM). All applicable guidelines for the care and use of animals from the respective facilities were followed. All animals were SIV-naïve and without history of induced inflammatory bowel disorders. All colon sections were fixed with 10% formalin before being imbedded in paraffin wax.

Collection of SIV-infected RM tissue

Fixed tissue blocks of colon from animals in a previously published study were examined [29]. Briefly, RM were intravaginally inoculated with SIVmac239 (105 TCID50) and randomly placed into one of three groups; those to be sacrificed at either days three (N = three), seven (N = three), or 14 (N = three) post-infection. Samples from these animals were compared with uninfected controls (N = three) for the expression of GrB in the intestinal LP by immunohistochemistry. Comparable samples from AGM or SM during acute SIV infection were not available.

Assessment of plasma LPS concentrations

Plasma samples from the aforementioned animals was assessed for LPS concentration using a limulus amoebacyte assay (Lonza, Walkersville, MD).

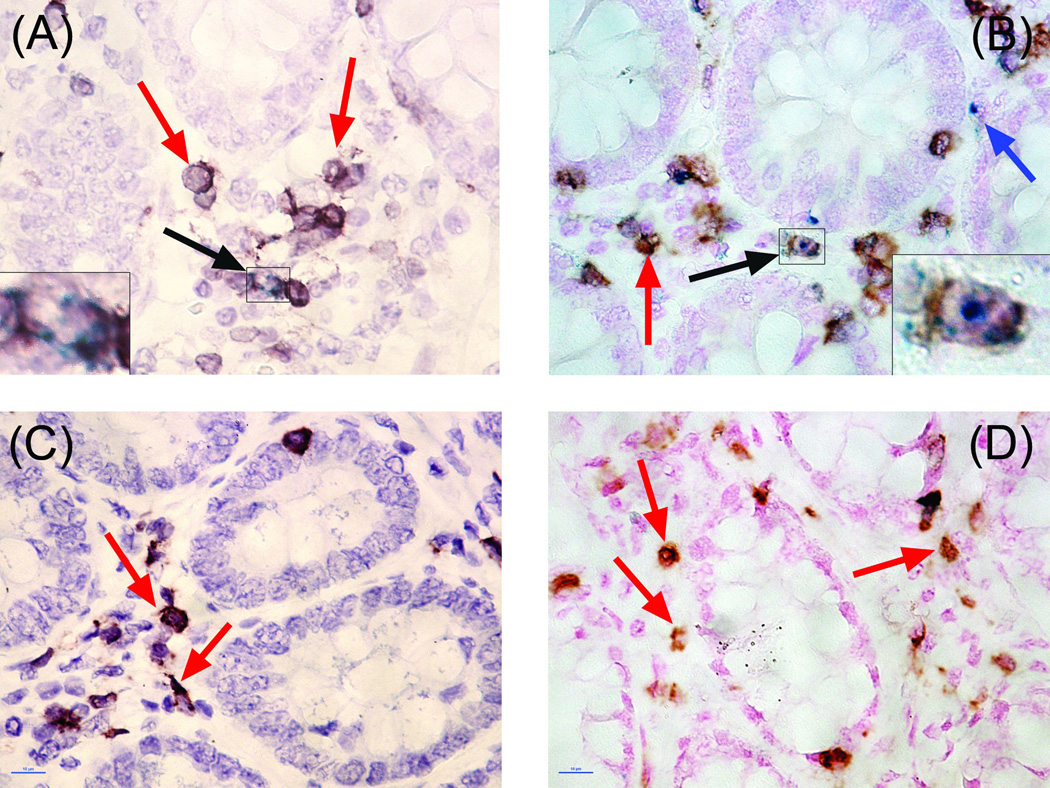

Detection of CD4, CD3, CD20, and GrB by immunohistochemistry

Paraffin embedded blocks of colon, duodenum, tonsil, spleen, and peripheral lymph node were sectioned at four µm. Slides were de-paraffinized and rehydrated by running them through xylene and graded alcohol. The sections were then subjected to high-temperature (~120°C in a pressure cooker) antigen retrieval for 25-min in an EDTA based solution (Borg Decloaker, pH 10.0, BioCare Medical, Concord, CA). Following antigen retrieval, slides were placed into Shandon Coverplates (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and blocked with 10% normal goat serum in a diluent buffer (Ventana, Tuscon, AZ) for 30-min. Sections were incubated with the first primary antibody (anti-CD4 clone 1F6, Novocastra; rabbit polyclonal anti-CD3, Dako; or anti-CD20 clone L26, Dako) overnight at four degrees Celsius. The sections were then washed three times with TBST and incubated with a goat, anti-mouse/anti-rabbit secondary polymer (Dako Envision Dual Link System-HRP, Dako, Carpenteria, CA) for 30-min at room temperature. Following a second wash in distilled water, sections were developed in either DAB (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) or Bajoran Purple (BioCare Medical). For double labeling of CD4 or CD3 with granzyme B, slides were placed into new Shandon Coverplates, re-blocked in 10% goat serum and incubated with the second primary antibody (anti-GrB clone GrB-7, Dako) overnight at four degrees Celsius. After incubation with the secondary polymer, slides were developed in TrueBlue (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Sections were counterstained in either nuclear fast red (Vector, Burlington, CA) or hemotoxylin (BioCare Medical) and coverslipped in a xylene based organic mounting medium (Krystalon, EMD, Darmstadt, Germany).

Light microscopy

Enumeration of CD4+, CD3+, and GrB+ cells was performed with a Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope equipped with NIS Elements AR software (Melville, NY). Only one technician, who was blinded to the species and the infection status of the slides, counted the cells. For the intestinal sections, ten non-overlapping images of the LP were taken from each slide. Using the Cell Counter function in ImageJ software (NIH), the total number of CD4+, CD3+, GrB+, and double positive cells (i.e. CD4+/GrB+ or CD3+/GrB+) were counted and normalized to total number of nuclei present in the LP, and presented as a percentage of positive cells per image. The values from each image were then averaged. For peripheral lymphoid tissues, single 10× images were taken and evaluated for the expression of CD3, CD4, and CD20.

Statistical methodology

Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS v18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Significance for all tests was set at P<0.05. Separate dependant samples t-Tests were used to compare the percentages of CD4+ and CD3+ cells in the intestinal LP within each species. Simple, one-way ANOVAs were used to compare the mean percentages of single and double positive cells present in the intestinal LP between species. A separate one-way ANOVA was used to analyze the differences in GrB expression in the intestinal LP of RM at days zero, three, seven, and 14 following infection with SIV. When significance was observed, a Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used to determine the location of significance. All values are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

The colonic LP of SIV-naive AGM and SM contain fewer CD4+/CD3+/GrB+ cells than do SIV-naive RM or PM

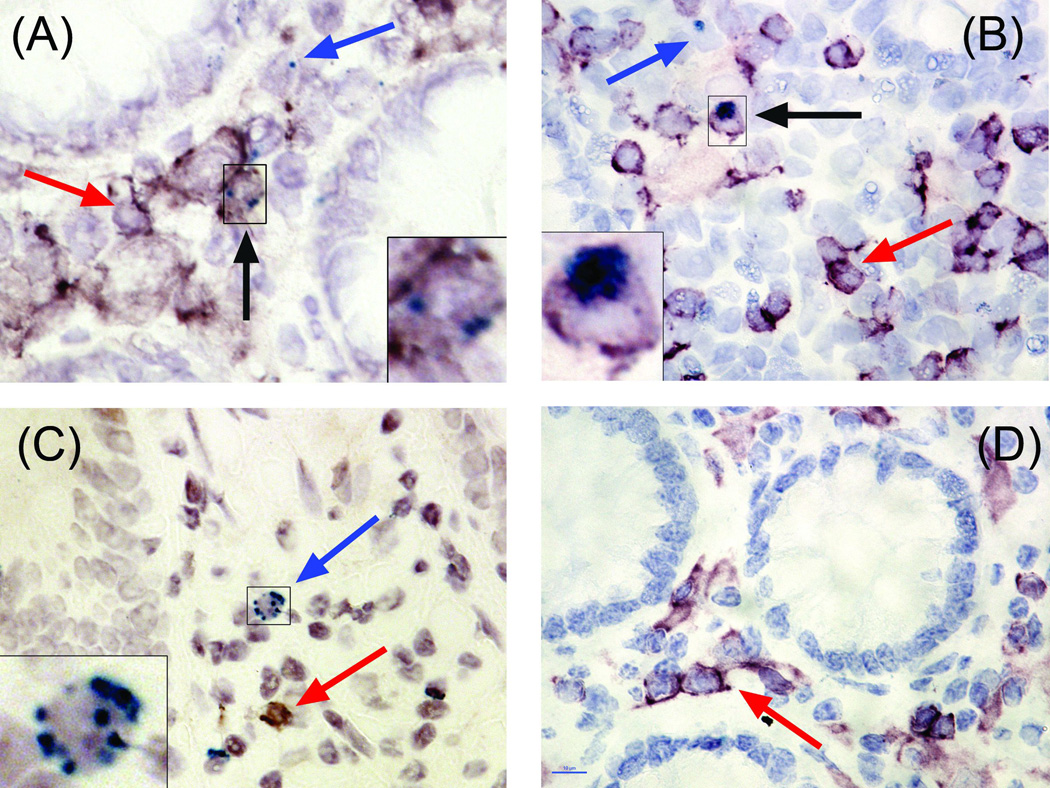

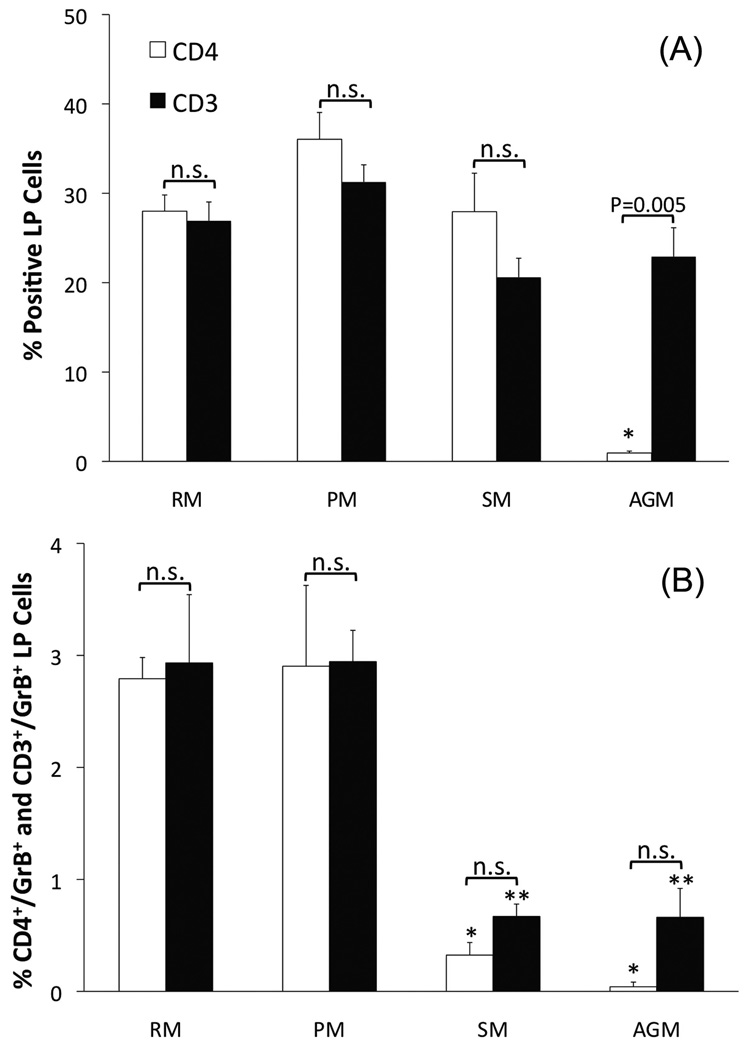

Rhesus macaques (2.79 ± 0.19%) and PM (2.90 ± 0.72%) have significantly larger proportion of CD4+/GrB+ cells in the LP of the colon than do SM (0.32 ± 0.11%, P < 0.01, Figures 1 and 3D). Unexpectedly, we found that there were very few cells that expressed CD4 in the colonic LP of SIV-naïve AGM. This was not due to technical issues since readily detectable CD4 expressing cells were visualized in the colonic isolated lymphoid follicle (ILF) of the same animals. Although most T cells in the LP are typically CD4+, it is possible that the GrB+ cells in the AGM LP are CD8+ T cells or NK cells. We detected CD8 in the RM LP and ILF (data not shown). However, after using four different antibodies (three monoclonal and one rabbit polyclonal) from three different vendors, we did not detect CD8 in either the LP or ILF of AGM. Other labs reported the same phenomenon with fixed intestinal tissues from several non-human primate species. It appears that the fixation process alters the CD8 epitope such that antibody binding is inhibited. We therefore measured the percentage of CD3+ cells in the LP of all four species and compared these values to the values found for CD4 expression in SM, RM, and PM. This strategy allowed for the elimination of confounding NK cells (i.e. CD3− cells) and an estimation of the number of CD8+ cells (i.e. %CD3+ cells - %CD4+ - %CD8+ cells). In the RM, PM, and SM colonic LP the percentage of CD4+ and CD3+ cells were similar and not statistically different, ranging from 20–36% (Figure 3A). This indicates, as expected, that most of the T cells resident in the LP are CD4+ T cells. Using the percentage of CD3+ cells in the AGM LP as a proxy measure of the percentage of CD4+ cells, similar to the SM, the AGM LP contains significantly fewer GrB+ T cells than found in the RM and PM (Figure 3B). Although we did not have the statistical power to test for the effects of gender or age, the low variability in GrB expression within each species, combined with equal numbers of both genders and a large spread in ages (2.1–20.2 yrs), suggest that neither of these variables played a role in our findings (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Table 1.

Animal demographics

| SIV naïve animals used to determine the frequency of GrB+/CD4+ T cells in the colonic LP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Animal ID | Gender | Age (yrs) |

| RM | A0354 | M | 2.3 |

| RM | A0655 | M | 2.1 |

| RM | A0710 | F | 19.6 |

| RM | A0737 | F | 19.1 |

| RM | A0353 | F | 2.5 |

| PM | 4085 | M | 9.0 |

| PM | A09160 | M | 1.8 |

| PM | K99329 | F | 11.0 |

| PM | M96164 | F | 14.0 |

| PM | T0039 | F | 10.6 |

| AGM | A07104 | F | 19.5 |

| AGM | A07107 | F | 19.6 |

| AGM | A09229 | M | 5.7 |

| AGM | A06133 | M | 20.2 |

| SM | FFZ | M | 10.5 |

| SM | FMZ | M | 10.4 |

| SM | FGA1 | M | 6.8 |

| SM | FUR | F | 16.7 |

| SM | FZZ | M | 9.5 |

| RM used to assess alterations in the number of GRB+ cells in the colonic LP following intravaginal SIV infection | |||

| Species | Animal ID | Gender | Group (Days post-infection) |

| RM | 27083 | F | Day 0 (SIV naïve) |

| RM | 31811 | F | Day 0 (SIV naïve) |

| RM | 33578 | F | Day 0 (SIV naïve) |

| RM | 28167 | F | Day 3 |

| RM | 28257 | F | Day 3 |

| RM | 29599 | F | Day 3 |

| RM | 28726 | F | Day 7 |

| RM | 27769 | F | Day 7 |

| RM | 30678 | F | Day 7 |

| RM | 28366 | F | Day 14 |

| RM | 26984 | F | Day 14 |

| RM | 32604 | F | Day 14 |

Acute SIV-infection or RM results in an increased expression of granzyme B in the intestinal LP

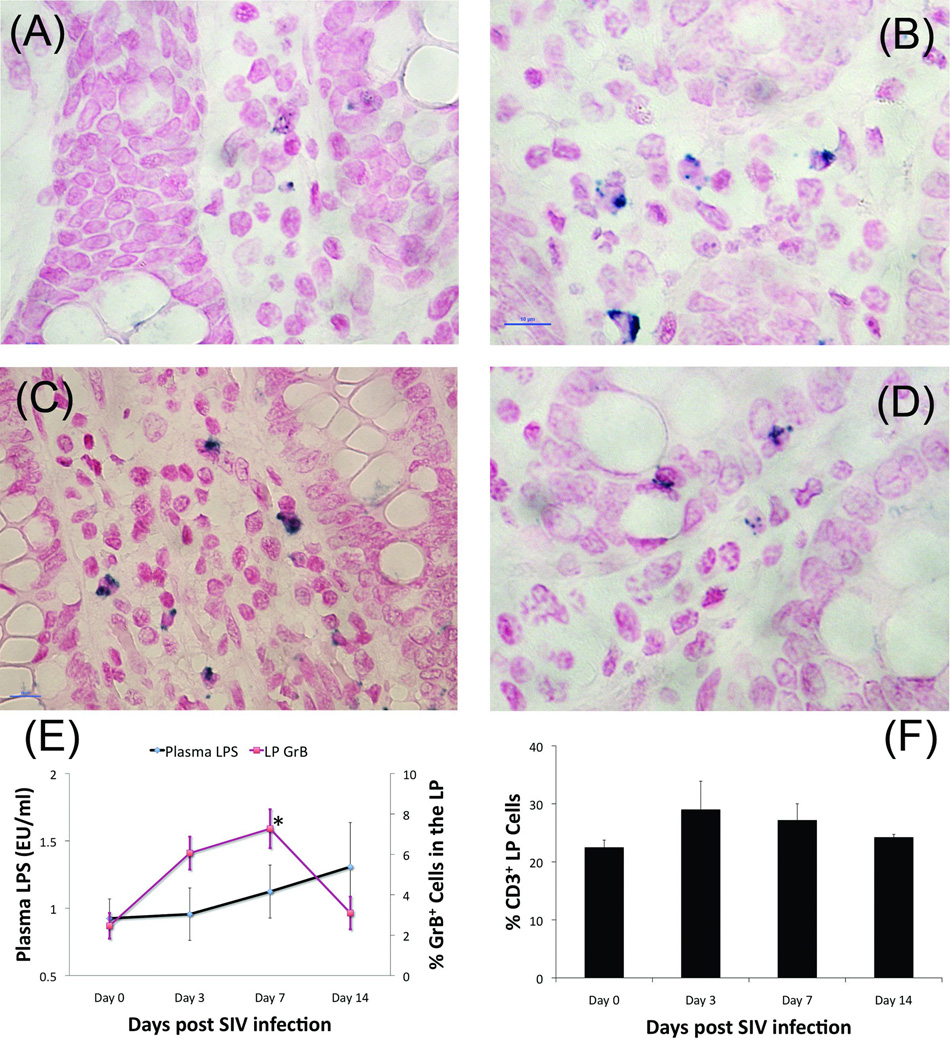

Within three days of SIV-inoculation of the RM, the number of cells staining positive for CD4 was dramatically reduced, likely as a result CD4 down-regulation resulting from SIV-mediated T cell activation (picture not shown). Using CD3 expression to approximate the percentage of CD4+ T cells in the LP, we observed no statistically significant changes in the percentage of T cells at any time point (22.5–28.9%) (Figure 4F). However, the percentage of cells expressing GrB trended towards an increase at day three post-infection (Figure 4B and 4E, P=0.084) and was significantly higher by day seven (Figure 4C and 4E, P=0.018). By day 14, the percentage of GrB positive cells had returned to baseline levels (Figure 4D and 4E). Levels of viremia measured in the serum, colon, and mesenteric lymph nodes were undetectable until day 14, at which point they increased to significant levels at each site, a dynamic typical for intravaginal infection (Table 2). Although not statistically significant, there was a trend towards increased plasma LPS concentration at each time point when contrasted with healthy controls (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Table 2.

SIV viral loads as a function of time post-infection

| Group (Days post-infection) |

Plasma SIVgag vRNA (log10 copies/ml) |

Colon SIVgag vRNA (log10 copiesµg tissue RNA) |

Mes. LN SIVgag vRNA (log10 copies/µg tissue RNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 (SIV naïve) |

< 1.70 ± 0.0 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 |

| Day 3 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 |

| Day 7 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 | < 1.70 ± 0.0 |

| Day 14 | 7.10 ± 0.20* | 5.73 ± 0.35* | 6.9 ± 0.24* |

SIV RNA was detected in the plasma, colon, and mesenteric lymph nodes of RM by 14-days post-intravaginal inoculation.

means significantly different than Day 0, 3, and 7, P<0.001.

Values represent means ± SEM.

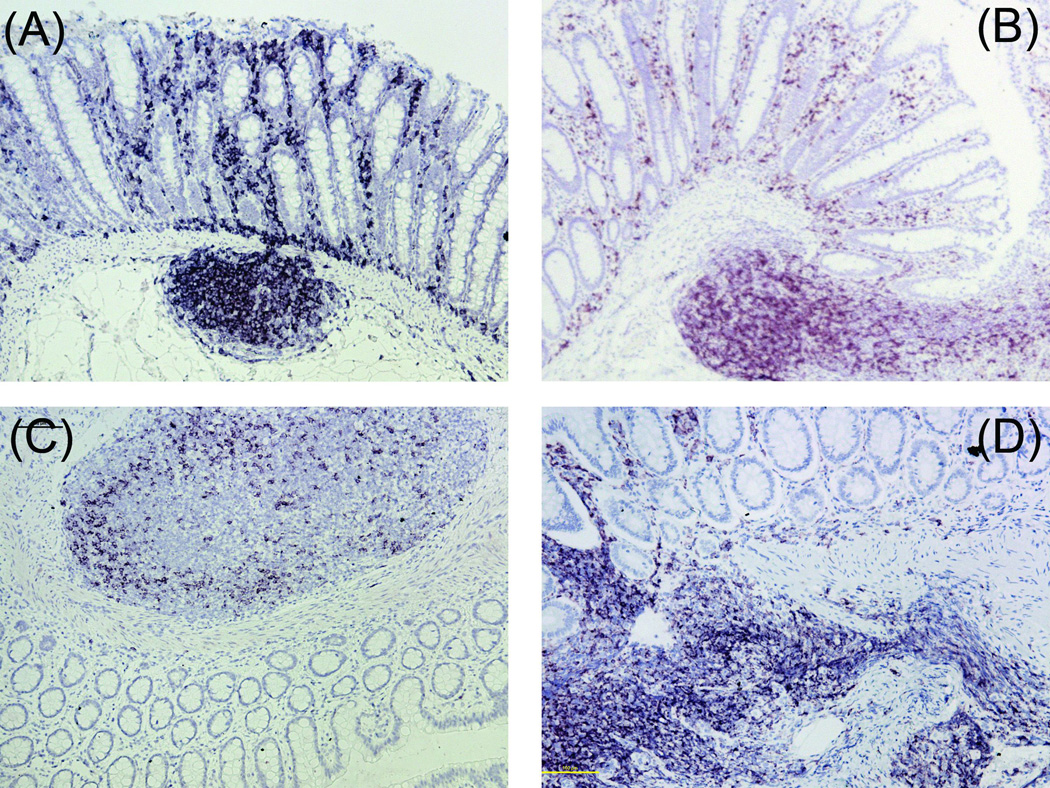

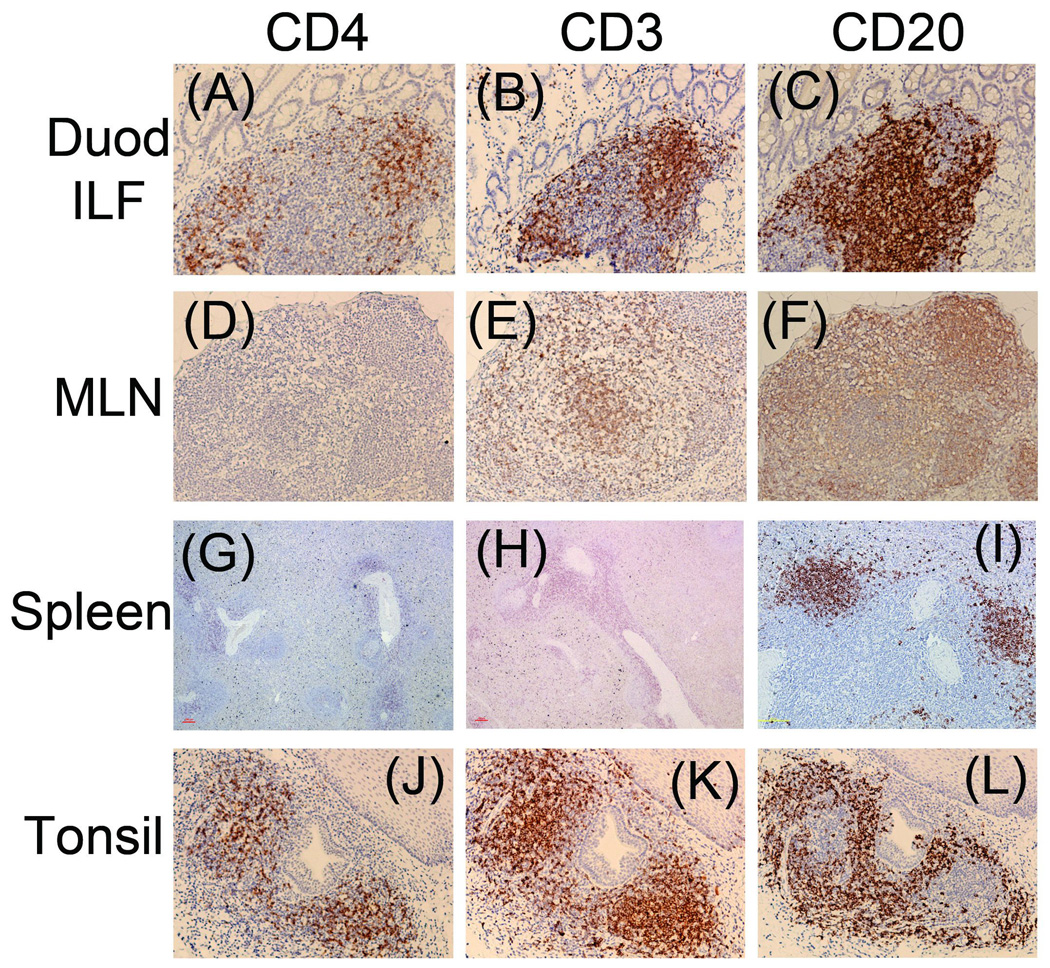

The colonic LP of SIV-naive AGM lacks CD4 expression

As stated previously, an unexpected result was the paucity in CD4 expressing cells in the LP of AGM (Figure 5C). This is in contrast to the readily detectable frequencies of CD4 expressing cells in the AGM colonic ILF from the same animals, eliminating poor antibody binding to AGM CD4 as the culprit. The presence of CD3 expressing cells in the AGM LP (Figure 2C) suggests that the reduction in CD4 expression in this compartment is not the result of reduced T cell numbers but more likely a down-regulation of the expression of CD4 on these particular T cells. However, since we could not detect CD8 expressing cells in these animals, we cannot discount the possibility that many of these cells are actually CD8+ T cells. For this reason, future prospective studies will utilize frozen intestinal samples, a method of preservation that allows for CD8 detection via IHC (personal communication from JE Schmitz, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center).

Figure 5.

Figure 2.

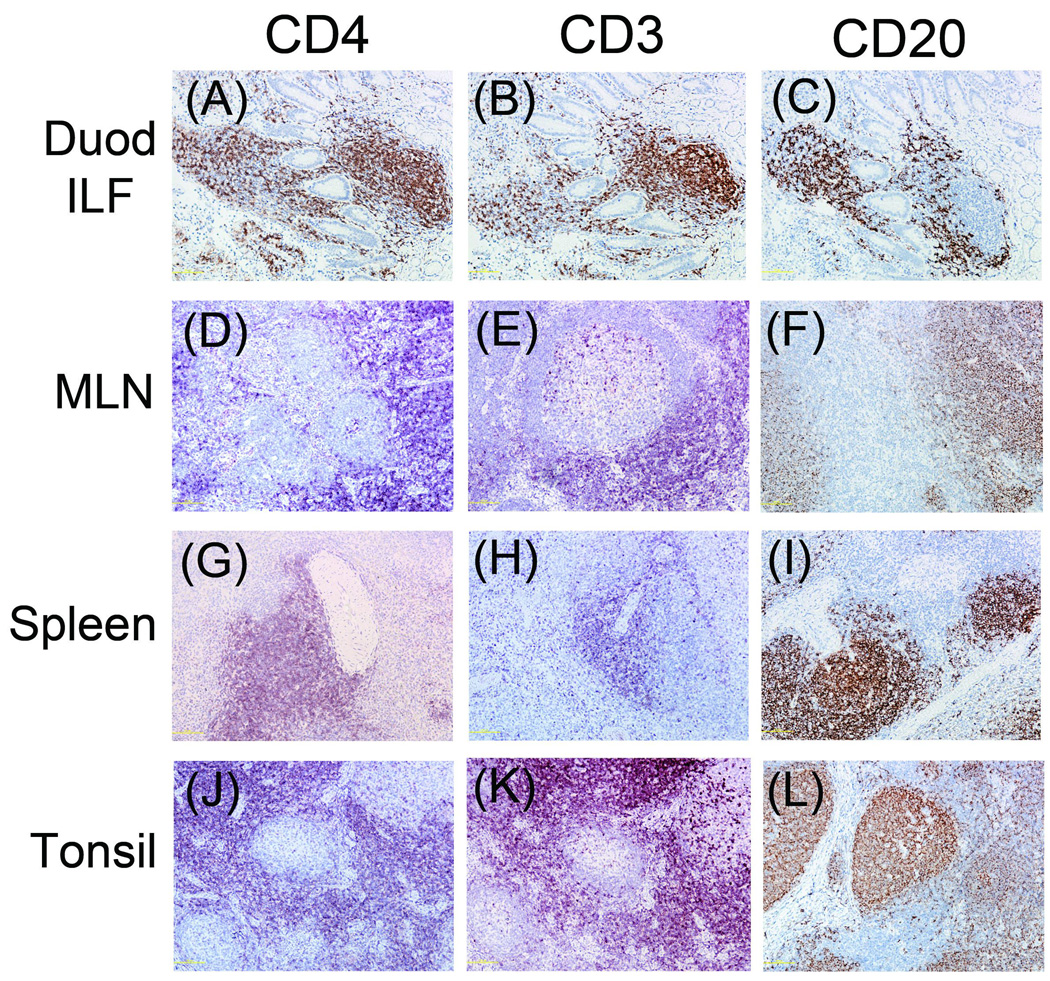

The expression of CD4 is undetectable in other key sites in SIV-naive AGM

Similar to what was observed in colonic tissue, CD4 expressing cells were nearly undetectable in AGM duodenal LP and mesenteric lymph node (Figures 6A and 6D), but were readily detectable in the duodenal ILF (Figure 6A). CD4 expression was moderately intense in AGM tonsil, but was marginal in the spleen (Figures 6G and 6J). In the AGM, both CD3 and CD20 (B cell marker) were detectable in all locations (Figures 6B, E, H, K, C, F, I, and L). By contrast, CD4, CD3, and CD20 stained strongly in the same tissues of RM (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

DISCUSSION

SIV infection of non-natural, Asian host species including RM and PM results in a specific series of downstream events, culminating in immune system collapse and simian AIDS. Regardless of the point of entry, SIV homes to the gut within a matter of days and by both direct (infection/activation) and indirect means (bystander killing) causes severe depletion of memory CD4 T cells in the intestinal LP [5]. During the same time frame, the integrity of the mucosal barrier may be compromised and luminal microbial products (e.g. LPS) traverse the epithelium and enter the peripheral circulation, providing a secondary stimulus that drives chronic, systemic immune activation [3, 9, 14, 21]. The degree of immune activation is the best predictor of the rate of disease progression in both SIV and HIV infection [15]. Although the natural hosts of SIV including AGM and SM experience some of these SIV-mediated effects, (e.g. high rates of viral replication, and depletion of intestinal and circulating CD4 T cells), they rarely experience microbial translocation, chronic immune activation, or simian AIDS [26, 27]. These differences in the etiology of SIV infection between pathogenic and non-pathogenic species suggest that the breach of the intestinal mucosal barrier is key to the different outcomes. There is published data supporting this idea. Chronically SIV-infected AGM, injected with exogenous LPS, experienced increased rates of viral replication, depletion of circulating CD4 T cells, and systemic immune activation, all of which diminished once the LPS was cleared from the circulation. These data also suggest that the lack of SIV pathogenesis in AGM is not the result of an intrinsic inability to respond to antigens such as LPS. Thus, the overriding question is whether or not there are inherent differences between the two animal models that protect AGM and SM from SIV-induced intestinal barrier damage while leaving RM and PM vulnerable.

Depletion of intestinal CD4 T cells in AGM and SM is not sufficient to induce microbial translocation in these species. We wondered whether injurious products could be released from infected/activated CD4 T cells and lead to disruption of ECM or TJ proteins between epithelial cells. Granzyme B was a candidate because of published data reporting that CD4 T cells activated in vitro release significant amounts of GrB into the supernatant [31]. Data from two other studies reported a role for GrB in the disruption of ECM and TJ proteins of urothelial and neuronal tissue respectively [7, 11]. We hypothesized that AGM and SM would inherently have significantly fewer intestinal CD4 T cells expressing GrB than RM and PM.

In support of our primary hypothesis, the findings of the current study demonstrate that the SIV-pathogenic species, RM and PM, have significantly more CD4 T cells that express GrB in the colonic LP than do SM, a natural, non-pathogenic, host of SIV. Although CD4 expression was not found in the AGM LP (a point to be discussed later), using the number of CD3+ cells as a proxy measure for CD4 expression, we observed a similar relationship between AGM and RM/PM. The reduced expression of GrB in CD4 T cells by AGM and SM may serve as an inherent protective mechanism against the harmful, down-stream effects of SIV infection, i.e. breach of the intestinal epithelial barrier, microbial translocation, chronic immune activation, and simian AIDS.

This contention is further supported by the fact that within seven days of SIV infection, expression of GrB in the intestinal LP of RM was significantly increased when contrasted with uninfected controls. Similarly, it has been reported that GrB expression is significantly elevated in peripheral lymph nodes of RM by 14-days after SIV infection [8]. In sharp contrast, SM had less GrB expression than RM at baseline and at each time point post-infection.

In the current study, by three days after infection, expression of CD4 was undetectable by IHC (data not shown). The proportion of CD3+ cells in the LP did not change over the course of the 14 days (Figure 4E), suggesting that the absence of CD4+ cells was not due to SIV-mediated depletion, but rather down-regulation following CD4-SIV interaction. Down-regulation of CD4 expression in RM following SIV infection has been reported [18]. The absence of detectable levels of SIV RNA until 14 days post-inoculation suggests that although the virus was likely present in the LP, replication had not reached levels that would trigger recruitment of either CD8 T cells or NK cells, (i.e. other possible sources of GrB). Rather, it is possible that resident CD4 T cells activated either by interaction with SIV or alterations in the cytokine milieu, up-regulated production and release of GrB into the microenvironment. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend towards increased plasma LPS levels at each subsequent time point after infection (Figure 4E). By 14 days post-inoculation, the number of GrB+ cells in the intestinal LP returned to baseline levels, likely indicating an overall depletion of these specific GrB+/CD4+ T cells. By this time, the damage to the mucosal barrier required to sustain a steady flow of microbial products may have already occurred [10].

Two studies in HIV+ humans reported increased GrB expression in the duodenal and colonic LP respectively [23, 28]. The first study found that 22 of the 29 HIV+ patients had between 5–10 GrB+ cells per high-powered field (hpf) in the duodenal LP. By contrast, duodenal samples from 13 of the 15 healthy controls contained zero to one GrB+ cell/hpf in the LP [28]. Similarly, another lab found that the percentage of GrB+ cells in the colonic LP was significantly higher in AIDS patients compared to healthy controls (2.2% and 0.2% respectively). When colon samples from AIDS patients co-infected with Cryptosporidiosis were examined, the proportion of GrB+ cells increased to 8.7% [23]. These findings suggest that interaction of LP lymphocytes with microbial products may amplify the release of GrB in a positive feedback loop whereby microbial translocation results in more GrB release that further damages the epithelium, thus allowing even more microbial translocation. In both instances, the GrB+ cells were assumed to be CD8 T cells. However, neither study confirmed this by double staining for CD8 and GrB. Future studies must show a causal link between interaction of SIV with CD4+ T cells resulting in GrB release and epithelial barrier dysfunction. Comparison of our current results from RM with acutely SIV-infected AGM and SM is also needed.

An unexpected result of our investigation was the reduction in CD4 expressing cells in the LP of the AGM colon and duodenum. By contrast, CD4 expressing cells were readily apparent in the RM colonic and duodenal LP and ILF. This was not the result of poor antibody cross reactivity as there was robust staining of CD4 in the ILF. The presence of CD3+ cells in the AGM LP in proportions similar to those observed in the other non-human primate species suggests that the absence of CD4 expression is not the result of reduced T cell numbers in this compartment. Rather, it is likely the CD4+ T cells are present but express a markedly reduced level of CD4 per cell that is below the threshold of detection by IHC techniques. Since we could not stain CD8, this contention remains unproven. However, even if these CD3+/CD4− T cells are actually CD8+ T cells, they do not express GrB, thus eliminating them as active participants in our model of a GrB mediated gut breach. The CD4+ T cells in the ILF are mainly naïve lymphocytes initially exposed to antigens delivered from the luminal surface, whereas those in the LP have a memory phenotype [25]. Since SIV preferentially infects memory CD4 T cells, down-regulation of CD4 expression may be a protective mechanism to reduce SIV binding and subsequent infection/activation in the LP, which is adjacent to the epithelium and thus a likely reservoir of substances that can cause a gut breach.

Based on this evidence, our current model is that CD4 protein expression in the AGM is reduced during the transit between the ILF and the LP. After encountering cognate antigen in the ILF, new memory CD4 T cells exit the ILF, entering the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) where they acquire the capacity to home to the gut. Once in the intestinal circulation, the CD4 T cells extravasate into the LP as effector memory cells. Although we did not observe CD4 staining in the MLN, another lab has reported that AGM express CD4 in this tissue, albeit at a much lower intensity than observed in RM MLN [20]. This suggests that downregulation of CD4 on T cells begins during transit between the ILF and the MLN. Again, the presence of CD3+ cells in the MLN means that normal levels of T cells are present. CD4 staining of AGM spleen and tonsil supports the hypothesis that reduced CD4 expression on T cells in the intestinal LP and MLN is an adaptive measure to avoid SIV-mediated damage to the intestinal mucosa and is not a generalized systemic phenomenon.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that reduction of CD4 expression occurs in the intestinal LP of AGM. However, a search of the relevant literature found both supporting and refuting evidence for the idea of CD4 down-regulation in AGM. An in vivo study in AGM observed that some naive CD4 T cells in the peripheral circulation shifted from a CD4bright phenotype to a CD4−/CD8dim phenotype as they entered the memory pool. These cells maintained functions classically attributed to CD4+ T cells, including production of IL-2 and IL-17, and expression of both FoxP3 and CD40 ligand [1]. The authors speculated that these alterations in CD4 expression in the memory pool were adaptive measures to avoid SIV infection.

Contrary to our findings, another lab published IHC images of CD4+ cells in the LP of AGM colon [20]. At first glance, the nuclear density of these areas is higher than we found in LP and closer to what was observed in the ILF. Because the three dimensional structure of intestinal tissue is complex, containing numerous twists, kinks, and folds on the macro- and micro-anatomical scale, a single four µm section often contains vertical, horizontal, and tangential cross sections of villi and the underlying LP. The areas of CD4 expression presented were horizontal cross sections with the villi appearing as circular areas embedded inside the LP. The depth of the sections is not known. It is therefore possible that the CD4+ cells observed in the previous publications are in the underlying ILF and not the LP. This possibility is shown in Figures 6a–c where a series of three vertical cross sections stained for CD4, CD3, and CD20 respectively (i.e. villi above an ILF) show how the boundary between the LP and ILF is not discrete but rather a heterogeneous mixture of compartments.

Others have reported CD4+ T cells in AGM intestine. It has been reported that by 14 days post SIV infection, both PM and AGM lose a significant number of CD4+ T cells from the colon [10]. However, the method of detection was flow cytometry. The specific procedure utilized by Favre et al. resulted in a single cell suspension that likely included all of the compartments of the colonic tissue (i.e. epithelium, LP, and ILF). It is thus impossible to know the origin of the CD4+ cells. Our data would suggest that these CD4+ cells were actually from the ILF and not the LP. In support of this idea is the fact that the healthy PM had a significantly higher percentage of colonic CD4+ cells than did the AGM (nearly two to one). A lack of CD4 expression in the LP of AGM could account for the difference in the percentage of colonic CD4+ cells between the two species. It is also possible that the difference in the number of CD4+ T cells between the PM and AGM is an inherent species difference, however, our data does not support this conclusion. We did not observe a difference in the percentage of LP T cells (i.e. CD3+) between PM and AGM (Figure 3A).

In the current study we observed that; 1. there are fewer GrB+ CD4 T cells in the LP of AGM and SM relative to the amount found in RM and PM, and 2. there is little CD4 expression in the AGM intestinal LP. A possible explanation for these two important observations is that millions of years of interaction between SIV and AGM/SM has generated evolutionary pressure on these natural hosts to develop mechanisms that reduce SIV pathogenesis. By contrast, the introduction of SIV into the RM, PM, and human species is a relatively recent event, occurring within the last few decades. Without the protective adaptations possessed by AGM and SM, the pathogenic species may be more susceptible to intestinal mucosal damage via GrB release into the LP. This rapidly leads to microbial translocation, chronic immune activation, and eventual collapse of the immune system. Clearly, further evidence is required to fully support this hypothesis. Future studies must focus on establishing a causal link between SIV infection of the intestinal LP, GrB release from infected/activated memory CD4 T cells, and damage to the mucosal epithelium. These differences between pathogenic and non-pathogenic species may provide valuable targets for future therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the NIAID and the Center for AIDS Research (CFAR). DE Lewis is supported by the Baylor/UTHealth CFAR (AI36628) and an NIH R37 merit award (AI36211). AT Hutchison is a recipient of an NIH T32 training grant (AI007456). JE Schmitz is supported by an NIH RO1 grant (AI065335).

We would also like to thank Dr. Cristian Apetrei (University of Pittsburgh), and Dr. Margaret Conner (Baylor College of Medicine) for their editorial reviews. Finally, we must thank the Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Bastrop, TX for providing us with colon samples used in preliminary data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beaumier CM, Harris LD, Goldstein S, Klatt NR, Whitted S, McGinty J, Apetrei C, Pandrea I, Hirsch VM, Brenchley JM. CD4 downregulation by memory CD4+ T cells in vivo renders African green monkeys resistant to progressive SIVagm infection. Nat Med. 2009;15:879–885. doi: 10.1038/nm.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenchley JM, Paiardini M, Knox KS, Asher AI, Cervasi B, Asher TE, Scheinberg P, Price DA, Hage CA, Kholi LM, Khoruts A, Frank I, Else J, Schacker T, Silvestri G, Douek DC. Differential Th17 CD4 T-cell depletion in pathogenic and nonpathogenic lentiviral infections. Blood. 2008;112:2826–2835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, Price DA, Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, Nguyen PL, Khoruts A, Larson M, Haase AT, Douek DC. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200:749–759. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummins NW, Badley AD. Mechanisms of HIV-assocated lumphocyte apoptosis: 2010. Celll Death and Disease. 2010;1:1–9. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cumont MC, Diop O, Vaslin B, Elbim C, Viollet L, Monceaux V, Lay S, Silvestri G, Le Grand R, Muller-Trutwin M, Hurtrel B, Estaquier J. Early divergence in lymphoid tissue apoptosis between pathogenic and nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infections of nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2008;82:1175–1184. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00450-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Eliseo D, Pisu P, Romano C, Tubaro A, De Nunzio C, Morrone S, Santoni A, Stoppacciaro A, Velotti F. Granzyme B is expressed in urothelial carcinoma and promotes cancer cell invasion. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:1283–1294. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estes JD, Gordon SN, Zeng M, Chahroudi AM, Dunham RM, Staprans SI, Reilly CS, Silvestri G, Haase AT. Early resolution of acute immune activation and induction of PD-1 in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys distinguishes nonpathogenic from pathogenic infection in rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2008;180:6798–6807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estes JD, Harris LD, Klatt NR, Tabb B, Pittaluga S, Paiardini M, Barclay GR, Smedley J, Pung R, Oliveira KM, Hirsch VM, Silvestri G, Douek DC, Miller CJ, Haase AT, Lifson J, Brenchley JM. Damaged Intestinal Epithelial Integrity Linked to Microbial Translocation in Pathogenic Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infections. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001052. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Favre D, Lederer S, Kanwar B, Ma ZM, Proll S, Kasakow Z, Mold J, Swainson L, Barbour JD, Baskin CR, Palermo R, Pandrea I, Miller CJ, Katze MG, McCune JM. Critical loss of the balance between Th17 and T regulatory cell populations in pathogenic SIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kebir H, Kreymborg K, Ifergan I, Dodelet-Devillers A, Cayrol R, Bernard M, Giuliani F, Arbour N, Becher B, Prat A. Human TH17 lymphocytes promote blood-brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nat Med. 2007;13:1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/nm1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klatt NR, Harris LD, Vinton CL, Sung H, Briant JA, Tabb B, Morcock D, McGinty JW, Lifson JD, Lafont BA, Martin MA, Levine AD, Estes JD, Brenchley JM. Compromised gastrointestinal integrity in pigtail macaques is associated with increased microbial translocation, immune activation, and IL-17 production in the absence of SIV infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhmann SE, Madani N, Diop OM, Platt EJ, Morvan J, Muller-Trutwin MC, Barre-Sinoussi F, Kabat D. Frequent substitution polymorphisms in African green monkey CCR5 cluster at critical sites for infections by simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm, implying ancient virus-host coevolution. J Virol. 2001;75:8449–8460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8449-8460.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leinert C, Stahl-Hennig C, Ecker A, Schneider T, Fuchs D, Sauermann U, Sopper S. Microbial translocation in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Journal of Medical Primatology. 2010;39:243–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z, Cumberland WG, Hultin LE, Prince HE, Detels R, Giorgi JV. Elevated CD38 antigen expression on CD8+ T cells is a stronger marker for the risk of chronic HIV disease progression to AIDS and death in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study than CD4+ cell count, soluble immune activation markers, or combinations of HLA-DR and CD38 expression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;16:83–92. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199710010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Horowitz A, Hurley A, Hogan C, Boden D, Racz P, Markowitz M. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200:761–770. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milush JM, Mir KD, Sundaravaradan V, Gordon SN, Engram J, Cano CA, Reeves JD, Anton E, O'Neill E, Butler E, Hancock K, Cole KS, Brenchley JM, Else JG, Silvestri G, Sodora DL. Lack of clinical AIDS in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys with significant CD4+ T cell loss is associated with double-negative T cells. J Clin Invest. 2011 doi: 10.1172/JCI44876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minang JT, Trivett MT, Barsov EV, Del Prete GQ, Trubey CM, Thomas JA, Gorelick RJ, Piatak M, Jr, Ott DE, Ohlen C. TCR triggering transcriptionally downregulates CCR5 expression on rhesus macaque CD4(+) T-cells with no measurable effect on susceptibility to SIV infection. Virology. 2011;409:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandrea I, Gaufin T, Brenchley JM, Gautam R, Monjure C, Gautam A, Coleman C, Lackner AA, Ribeiro RM, Douek DC, Apetrei C. Cutting edge: Experimentally induced immune activation in natural hosts of simian immunodeficiency virus induces significant increases in viral replication and CD4+ T cell depletion. J Immunol. 2008;181:6687–6691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandrea IV, Gautam R, Ribeiro RM, Brenchley JM, Butler IF, Pattison M, Rasmussen T, Marx PA, Silvestri G, Lackner AA, Perelson AS, Douek DC, Veazey RS, Apetrei C. Acute loss of intestinal CD4+ T cells is not predictive of simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J Immunol. 2007;179:3035–3046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piche T, Barbara G, Aubert P, Bruley des Varannes S, Dainese R, Nano JL, Cremon C, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, Galmiche JP, Neunlist M. Impaired intestinal barrier integrity in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: involvement of soluble mediators. Gut. 2009;58:196–201. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.140806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raffatellu M, Santos RL, Verhoeven DE, George MD, Wilson RP, Winter SE, Godinez I, Sankaran S, Paixao TA, Gordon MA, Kolls JK, Dandekar S, Baumler AJ. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat Med. 2008;14:421–428. doi: 10.1038/nm1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reijasse D, Patey-Mariaud de Serre N, Canioni D, Huerre M, Haddad E, Leborgne M, Blanche S, Brousse N. Cytotoxic T cells in AIDS colonic cryptosporidiosis. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:298–303. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.4.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarin A, Williams MS, Alexander-Miller MA, Berzofsky JA, Zacharchuk CM, Henkart PA. Target cell lysis by CTL granule exocytosis is independent of ICE/Ced-3 family proteases. Immunity. 1997;6:209–215. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigmundsdottir H, Butcher EC. Environmental cues, dendritic cells and the programming of tissue-selective lymphocyte trafficking. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:981–987. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silvestri G. AIDS pathogenesis: a tale of two monkeys. J Med Primatol. 2008;37 Suppl 2:6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2008.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silvestri G, Paiardini M, Pandrea I, Lederman MM, Sodora DL. Understanding the benign nature of SIV infection in natural hosts. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:3148–3154. doi: 10.1172/JCI33034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snijders F, Wever PC, Danner SA, Hack CE, ten Kate FJ, ten Berge IJ. Increased numbers of granzyme-B-expressing cytotoxic T-lymphocytes in the small intestine of HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;12:276–281. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stone M, Ma ZM, Genesca M, Fritts L, Blozois S, McChesney MB, Miller CJ. Limited dissemination of pathogenic SIV after vaginal challenge of rhesus monkeys immunized with a live, attenuated lentivirus. Virology. 2009;392:260–270. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trapani JA, Jans DA, Jans PJ, Smyth MJ, Browne KA, Sutton VR. Efficient nuclear targeting of granzyme B and the nuclear consequences of apoptosis induced by granzyme B and perforin are caspase-dependent, but cell death is caspase-independent. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27934–27938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang T, Allie R, Conant K, Haughey N, Turchan-Chelowo J, Hahn K, Rosen A, Steiner J, Keswani S, Jones M, Calabresi PA, Nath A. Granzyme B mediates neurotoxicity through a G-protein-coupled receptor. FASEB J. 2006;20:1209–1211. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5022fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]