Abstract

Background

A large body of research has documented the prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms, especially vasomotor symptoms, in breast cancer survivors and their impact on quality of life. Urinary symptoms as part of the constellation of menopausal symptoms, however, have received relatively little attention. Thus, less is known about the prevalence and severity of urinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of studies published between 1990 and 2010 to describe the prevalence and severity of urinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors.

Results

We identified 16 eligible studies involving more than 2,500 women. Studies varied with respect to purpose, design, and nature of samples included; the majority used the same definition and assessment approach for urinary symptoms. Prevalence rates for symptoms ranged from 12% of women reporting burning or pain on micturition to 58% reporting difficulty with bladder control. Although in many studies the largest percentage of women rated symptoms as mild, as many as 23% reported severe symptoms.

Conclusions

Mild to moderate urinary symptoms are common in breast cancer survivors and some women report severe symptoms. Symptoms appear to adversely affect women’s quality of life. There is a need for additional research assessing the natural history of urinary symptoms using consensus definitions and validated measures in diverse populations. Nevertheless, this review suggests that clinicians should screen for urinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors and offer treatment recommendations or make referrals as appropriate.

Keywords: breast cancer, menopause, urogenital system, survivorship

Introduction

Women with a history of breast cancer currently account for approximately 22% of cancer survivors in the United States, making them the largest group of cancer survivors today.1 With ongoing advances in early detection and treatment, this trend is likely to continue. Nearly 90% of women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer are expected to survive five years or more following diagnosis.2, 3 As a result, interest has shifted increasingly to include the prevention and treatment of long-term and late effects of breast cancer and its treatment. As well, national cancer research goals include a focus on survivorship issues to improve health-related outcomes and enhance quality of life in survivorship.4 Consistent with this, the loss of menses due to chemotherapy and the menopausal transition have received considerable attention in breast cancer survivorship research.

Symptoms of menopause in women with breast cancer are typically the result of ovarian suppression and failure secondary to chemotherapy in premenopausal women and the use endocrine therapy in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women.5, 6 These symptoms are often more severe than those experienced with natural menopause.7-9 To date, a relatively large body of research has documented the prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms, especially vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats and genital symptoms such as vaginal dryness, in breast cancer survivors, and their impact on quality of life in survivorship. Urinary symptoms are also commonly associated with menopause9-12 and include urgency, urgency incontinence, stress incontinence, dysuria or burning, pelvic pressure and frequency, recurrent urinary tract infections and dryness.6 Estrogen receptors have been identified in the structures of the lower urinary and genital tracts, including the uterus, vagina, ovaries, bladder, urethra, external genitalia and pelvic floor muscles. Thus, researchers have postulated that the development of urinary symptoms in menopause may be the result of lower urinary tract atrophy secondary to estrogen deficiency.10, 12-15 Urinary symptoms may occur after other menopausal symptoms such as vasomotor symptom have abated.6 And unlike menopausal vasomotor symptoms, if left untreated, urinary symptoms continue throughout life and may even worsen over time.16, 17

Research in women in the general population has consistently demonstrated that urinary symptoms adversely affect women’s quality of life18-20 and that the impact of these symptoms is determined by type and severity of symptoms.21, 22 Treatment options for urinary symptoms associated with menopause depend on the symptom and its severity.17 There are a number of non-invasive, behavioral interventions available to treat mild to moderate symptoms.17, 23-26 Many women with urinary symptoms, however, do not seek treatment because of embarrassment, a misconception that symptoms are a normal part of aging, uncertainty about available treatment options, or the belief that they can cope on their own.19, 27-30

Despite the attention to menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors, urinary symptoms as part of the constellation of menopausal symptoms appear to have received little attention. As a result, less is known about the prevalence and severity of urinary symptoms and their impact on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. We conducted a systematic literature review to identify studies that assessed urinary symptoms as part of the constellation of menopausal symptoms in women with a diagnosis of breast cancer. The aims of this paper are to review and characterize the available scientific literature with respect to urinary symptoms and breast cancer and to describe the prevalence and severity of urinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Search and Selection Strategy

The identification of relevant studies began with electronic searches of English language journal articles in Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL from 1990 through June 2010. The MeSH search terms used were “breast neoplasms” and “menopause.” The first two authors (K.A.D. and A.R.B.) separately screened study abstracts based on two eligibility criteria. The first was that each study must have been published in a peer-reviewed English language journal. The second was that each study had to report on the quantitative assessment of any urinary symptom in the context of menopausal symptoms and breast cancer. Articles that reported menopausal symptoms but that did not include urinary symptoms as part of the constellation of symptoms were excluded. Similarly, articles involving qualitative assessments of menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer and reviews of existing research that summarized results of published studies on menopause in women with breast cancer were excluded. Reference lists from studies retrieved also were reviewed to ensure all possible studies were identified.

Review and Data Extraction

The first two authors (K.A.D. and A.R.B.) separately reviewed the retrieved studies and extracted data from all of the studies that met eligibility criteria using a standardized form. Data extracted included basic descriptive information from each study about participants, including demographic and clinical characteristics, the purpose and design of the study, and the manner in which menopausal symptoms, including urinary symptoms were assessed. Extraction of results focused on published findings that provided information about urinary symptoms in women with a diagnosis of breast cancer. Any discrepancies in study eligibility criteria and data extraction were discussed and consensus was reached. Bias was reduced by conducting a comprehensive search of published studies in several electronic databases and searching reference lists of published reviews.

Results

Search Results and Nature of Selected Studies

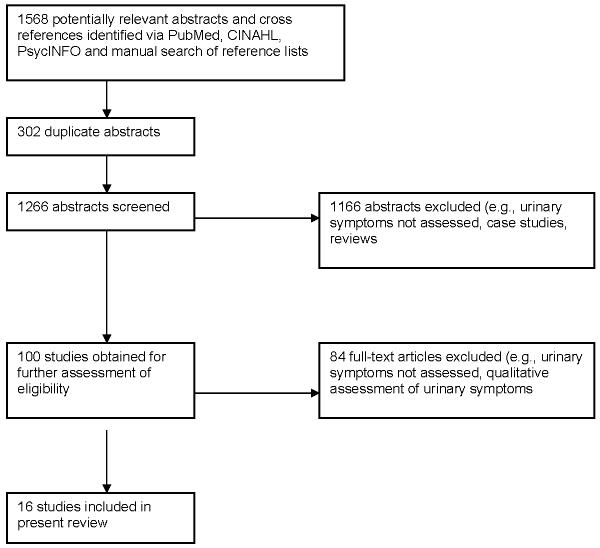

Of 1266 abstracts screened, 1166 did not meet eligibility criteria (Figure 1). The complete texts of 100 published studies were retrieved and an additional 84 were excluded based on eligibility criteria. As a result, 16 publications were included in this review (Table 1).31-46 Thirteen of the identified studies were conducted in the United States while the remaining three studies were conducted in Belgium,38 Canada,46 and the United Kingdom.43 The nature and purpose of each study varied widely. Five studies focused specifically on the prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer;31, 32, 43-45 two of these five studies tested an intervention focused, at least in part, on relieving menopausal symptoms.32, 45 Four studies focused on treatments for breast cancer and their relationship to menopausal symptoms.35, 37, 38, 46 Two studies41, 42 evaluated the psychometric properties of a modified version of the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) Symptom Checklist, a 43-item checklist from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project, a multi-center chemoprevention trial evaluating the efficacy of tamoxifen.47 Another study used an early version of the BCPT Symptom Checklist to identify particular “problem areas” women experienced after breast cancer.36 Three studies described quality of life,33, 34, 40 including sexual function, after breast cancer, and included the assessment of menopausal symptoms in their assessment battery. Finally, one study assessed factors associated with hospitalization after breast cancer.39 With respect to study design, the 16 studies identified included 10 cross-sectional studies, 4 longitudinal studies, and 2 randomized controlled intervention trials.

Figure 1.

Study identification.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

| Authors | Study Design | Sample Size |

Age in Years (Mean and SD, Range) |

Race/Ethnicity | Disease Characteristics |

Treatment Characteristics | Menopausal Status | Position in Disease / Treatment Trajectory |

Time Since Diagnosis / Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfano et al., 200642 |

Longitudinal | 803 | 56 (10), range = 29 to 86 |

White 60.4%, Black 24.8%, Hispanic 11.8% |

Localized 56.4%, Regional 21.4%, In situ 22.2% |

Surgery only 32.3%; surgery/radiotherapy 36.9%; surgery/chemotherapy 9.2%; surgery/radiation/chemotherapy 21.7% |

24 mo. Assessment: premenopausal 18.3%; postmenopausal 75.9%; unclassifiable 5.8%; taking tamoxifen 45% |

Post-treatment when checklist administered |

Mean of 40.5 (6.5) months |

| Avis et al., 200436 |

Cross-sectional | 204 | 43.5 (6.2) | Caucasian 96%, African American 2%, Other 2% |

Stage I, II, or III | No mastectomy 56.5%; mastectomy, no reconstruction 20.0%; mastectomy, reconstruction 23.5%; initial chemotherapy 74.9%; initial radiation 69.3% |

Not reported | No current treatment 70.30%; initial treatment ongoing 11.88%; initial treatment ended 17.82%; currently undergoing treatment |

23.32 (9.8) range = 4 to 42 months |

| Avis et al., 200540 |

Cross-sectional | 202 | 43.5 (6.2) | White 96% | Stage I, II, III, or recurrent disease |

No mastectomy 56.6%; mastectomy, no reconstruction 19.7%; mastectomy, reconstruction 23.7%; initial chemotherapy 75.1%; initial radiation 69.6% |

Not reported | No current treatment 70.5%; initial treatment ongoing 12%; initial treatment ended 17.5%; currently undergoing treatment |

23.32 (9.8) range = 4 to 42 months |

| Chin et al., 200946 |

Cross-sectional | 251 | 60.5 (10.79), range = 32 - 91 |

Not reported | Early stage 84%, Metastatic 16% |

Endocrine therapy for early stage 84%; being treated for metastatic disease 16%; on tamoxifen 31%; on aromatase inhibitor 69% |

Postmenopausal 100% | Not reported | Not Reported / Mean duration of endocrine treatment = 23 months (range = 1 - 84 months) |

| Couzi et al., 199531 |

Cross-sectional | 190 | 54.9 (6.1), range = 41 to 65 |

White 83%, Black 14%, Other 3% |

In situ BC 15%, Invasive locoregional 85% |

Surgery only with or without radiation 37%; adjuvant therapy in form of chemotherapy, tamoxifen or both 63%; Tamoxifen at time of survey 35% ; ERT at some time before diagnosis 29% |

Postmenopausal | Post-treatment, 35% taking tamoxifen |

Not reported / Not reported |

| Ganz et al., 200032 |

Randomized controlled trial |

72 | 54.5 (5.9) | Asian (n=1) 1.4%, Black (n=5) 7%, Hispanic (n=1) 1.4%, White (n=65) 90% |

Stage I or II | Lumpectomy 67% (n=48); mastectomy 33% (n=24); tamoxifen 56% (n=40); prior radiation 69% (n=50); prior chemotherapy 47% (n=34) |

Mean of 6.9 (7.3) years postmenopausal |

Between 8 months and 5 years after diagnosis; completed treatment at least 4 months prior |

2.5 years (1.3) |

| Ganz et al., 200234 |

Longitudinal | 763 | 55.6 initial survey; 58.5 at follow-up |

White 83.5%, Black 8.9%, Other 7.6% |

Stage I or II | Lumpectomy 52.6%; mastectomy 28.5%; mastectomy with reconstruction 18.9%; received chemotherapy 42.2%; on tamoxifen 48.4% |

Not reported | Between 1 and 5 years post diagnosis at first assessment. Between 5 and 10 years post diagnosis at follow-up |

Mean 6.3 years (range = 5.0 to 9.5) |

| Ganz et al., 200335 |

Cross-sectional | 577 | 49.5, range = 30 - 61.6 |

White 70.2%, African American 11.6%, Hispanic 7.3%, Asian 8.5%, Other 2.4% |

Stage 0, I, or II | Lumpectomy 55.8%; mastectomy 44.2%; reconstruction 23.3%; received adjuvant therapy 62.0%; ever use tamoxifen 37.4%; current tamoxifen 18.0%; adjuvant therapy: none 27.5%, tamoxifen only 10.4%, chemotherapy only 35.0%, tamoxifen and chemotherapy 27.0% |

Premenopausal 16%, perimenopausal 13%, postmenopausal 60%, unclassifiable 11% |

Disease free between 2 and 10 years without recurrence / post treatment |

5.9 (1.5) years |

| Greendale et al., 200133 |

Cross-sectional | 61 | 54.5, range = 43.1 - 70.3 |

White 92%, Non-White 8% |

Stage I - II | Mastectomy 38%; lumpectomy 62%; current tamoxifen 61%; past chemotherapy 46% |

Postmenopausal | At least 8 months but not more than 5 years post diagnosis; completed chemotherapy or radiotherapy at least 4 months before enrollment |

2.4 years, range = .8 - 5.6 |

| Gupta et al., 200643 |

Cross-sectional | 200 | 53.9 (8.21), range = 29 to 65 |

Caucasian 95.2%, Afro-Caribbean 1.1%, Asian 3.7% |

Not reported | Chemotherapy 42%; radiotherapy to lower abdomen or pelvis 2.5%; bilateral oophorectomy 2.5%; GnRH analog 3.0%; tamoxifen 56.0%; anastrozole 7.5% |

Premenopausal 6.1%, perimenopausal 9.1%, postmenopausal 65.5%, hysterectomy 19.3% |

Received treatment within last 5 years |

> 5 years = 8%, 3 - 5 years = 20%, 1 - 3 years = 56%, < 1 year = 16% |

| Land et al., 200437 |

Longitudinal | 160 | ≤ 49 = 50.6%; 50 - 59 = 32.5%; ≥ 60 = 16.9% |

White 74.4%, Black 18.8%, Other 3.7%, Unknown 3.1% |

Axillary node- negative estrogen receptor-negative |

Surgery: lumpectomy + AD = 58.1%; modified radical = 41.9%; receiving AC or CMF |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Leining et al., 200644 |

Cross-sectional | 371 | 36.2 | Caucasian 89%, African American 2%, Other 9%, Missing 1% |

Stage 0 - III | Radiation 65%; mastectomy 58%; no systemic treatment 6%; chemotherapy 89%; tamoxifen 49%; ovarian suppression 15%; aromatase inhibitors 4%. At time of survey: Tamoxifen only 36%, ovarian suppression 9%, & aromatase inhibitors only 3% |

Not reported | At least one year post diagnosis |

1 - 2 years 53%, 3 - 5 years 33%, equal to or greater than 6 years 14% |

| Morales et al., 200438 |

Longitudinal | 164 | 62 | Not reported | Not reported | Adjuvant hormonal treatment 80% (n = 132); palliative treatments 20% (n = 32) |

Mean of 10 years postmenopausal |

Scheduled to start endocrine treatment |

Not reported |

| Oleske et al., 200439 |

Cross-sectional | 123 | 58.3 (4.0) | White 93% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | At least one year from therapy |

3.6 (2.6) years |

| Schover et al., 200645 |

Randomized controlled trial |

48 | 49.29 (8.3), range = 30 to 77 |

African American 100% |

Stage 0 to IIIA | Mastectomy without reconstruction 33% (n=16); mastectomy with reconstruction 19% (n=9); breast conservation 48% (n=23); past chemotherapy 74% (n=34); tamoxifen only in past 17% (n=8); tamoxifen currently 25% (n=12); currently taking other hormonal therapy 4% (n=2) |

Currently having menstrual cycles 19% (n=9) |

At least one year from diagnosis; had completed treatment except hormonal therapy, not undergoing breast reconstruction |

4.52 (3.8) years |

| Stanton et al., 200541 |

Cross-sectional | Sample 1: 863; Sample 2: 577; Sample 3: 560; Sample 4: 208 |

Sample 1: 56 (11.5), range = 31- 88; Sample 2: 50 (5.6), range = 30- 62; Sample 3: 57 (11.4), range = 27- 87; Sample 4: 47 (7.3), range = 20- 66 |

Sample 1: White 77%, Black 14%, Other 9%; Sample 2: White 70%, Black 12%, Other 16%; Sample 3: White 86%, Black 7%, Other 7%; Sample 4: White 96%, Black 3%, Other 1% |

Sample 1: 0 - II; Sample 2: 0 - II; Sample 3: I - II; Sample 4: High risk |

Chemotherapy: Sample 1: 38%; Sample 2: 62%; Sample 3: 50%; Sample 4: NA. Surgery (lumpectomy) Sample 1: 51%; Sample 2: 56%; Sample 3: 67%; Sample 4: NA. Tamoxifen (current) Sample 1: 47%; Sample 2: 18%; Sample 3: 54%; Sample 4: 0 |

Not reported | Sample 1: diagnosed 1 - 5 years earlier; Sample 2: disease free for 2 - 10 years; Sample 3: recently completed treatment; Sample 4: NA |

Sample 1: 36 mos, range = 10 - 78; Sample 2: 71 mos, range = 18 - 140; Sample 3: 7 mos, range = 1 - 19; Sample 4: NA |

BCPT = Breast Cancer Prevention Trial Symptom Checklist from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project

QOL = quality of life

BCS = breast cancer survivors

BC indicates breast cancer

CMF chemotherapy regimen = cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil

AC chemotherapy regimen = doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide

AD = axillary node dissection

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

All but one of the studies reported mean age of the sample which ranged from 36 to 62 years. Eight of these studies also reported age range; women as young as 27 years35, 36, 40, 41, 46 and as old as 91 years were included. Three studies included only women who were 50 years of age or younger at diagnosis and one study44 included only women who were 40 years of age or younger at diagnosis. Fourteen studies provided race and/or ethnicity information for participants. Across these studies, a mean of 84% of women were classified as white (range = 60% to 96%) and a mean of 17% were classified as black or African American (range = 1% to 100%).

With respect to disease characteristics, 13 studies provided information about disease stage. Across studies, the majority of patients had stage I – III disease; some patients had stage 0 disease and some had recurrent disease. Ten studies reported mean time since diagnosis; this ranged from 7 months to 6.3 years. Five of these studies also reported the range of time since diagnosis; the shortest time since diagnosis was 1 month41 while the longest was 11.7 years.41 With respect to position in the treatment trajectory, one study37 included only women in active treatment. Twelve studies included only women who had completed adjuvant therapy. Of these, 10 studies specified whether the women were receiving endocrine therapy after having completed adjuvant therapy. Two studies were exclusive to women receiving endocrine therapy for early stage or advanced breast cancer.38, 46 And finally, two studies,36, 40 drawn from the same sample of women, included both women who were post-treatment or in active treatment.

Thirteen studies provided detail about adjuvant therapies received by study participants. Each of these studies included women who had received some combination of surgery and chemotherapy; most studies also included women who had received radiotherapy. No samples were comprised exclusively of women who had undergone surgical resection and chemotherapy, with or without radiotherapy. For example, in the study by Alfano et al.,42 32.3% had undergone surgery only, 36.9% surgery plus radiotherapy, 9.2% surgery plus chemotherapy, and 21.7% surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy; 45% were on tamoxifen. As noted previously, one study37 involved women in active treatment with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) with standard cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) and tamoxifen or placebo after surgical resection. As also noted previously, most studies included information about whether the women were currently receiving endocrine therapy. Of those studies that provided no detail about adjuvant therapy with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, two studies38, 46 limited participation to those women who were currently receiving endocrine therapy.

Assessment of Menopausal Symptoms

The assessment of menopausal symptoms varied minimally across studies (Table 2).31-46 Twelve studies utilized a modified version of the 43-item BCPT Symptom Checklist. The checklist is a measure of common physical and psychological symptoms as well as symptoms associated with menopause and tamoxifen use. Respondents are asked to rate how bothered they were by each symptom during the past four weeks, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “not at all,” 1 = “slightly,” 2 = “moderately,” 3 =“quite a bit,” to 4 = “extremely.” The versions used in the 12 studies included an early 50-item version that was later modified for use in the BCPT,39 42-item versions35 16-item versions,42, 44 15-item versions,36, 40 and an “abbreviated” version with the number of items not specified.34 One study37 used a symptom checklist constructed from existing instruments including the BCPT Symptom Checklist. Four used the 7-item Menopausal Symptom Scale adapted from the 43-item BCPT checklist.32, 33, 41, 45 The study by Stanton et al.41 used both the 42-item version of the checklist and the 7-item Menopausal Symptom Scale.

Table 2.

Assessment of menopausal and urinary symptoms by studies included in the systematic review

| Authors | Assessment of Menopausal Symptoms |

Assessment of Urinary Symptoms | Prevalence/Severity of Urinary Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alfano et al., 200642 |

16 items from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past year, difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying and difficulty with bladder control at other times; bother: 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely |

Difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying = 46% (mean severity = 1.8 (0.9)); difficulty with bladder control at other times = 58.2% (mean severity = 1.8 (1.0)) |

| Avis et al., 200436 |

15 items from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, how bothered have you been by difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying / at other times (1 = not at all to 5 = very much) |

Bladder control - laughing: not at all 74.8%, a little 9.9%, somewhat 8.9%, quite a bit 4.0%, very much 2.5%; bladder control - other: not at all 73.9%, a little 14.3%, somewhat 6.4%, quite a bit 3.5%, very much 2.0%; difficulty with bladder control reported as bothersome by less than 30% |

| Avis et al., 200540 |

15 items from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, how bothered have you been by difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying / at other times (1 = not at all to 5 = very much) |

Difficulty with bladder control (age categories): 25-34 (n=25), 16%; 35-39 (n=41), 22.0%; 40-44 (n=54), 30.2%; 45-50 (n=82), 51.2%; Total N = 202, 35.3%; p = .0007 - problems increased with age |

| Chin et al., 200946 |

FACT-ES | In past 7 days, 4 questions about urinary tract symptoms since endocrine therapy; asked to indicate how true a statement was for them: 0 = not at all to 4 = very much |

Dysuria, none = 87%, mild (1/2) = 10%, moderate/severe (3/4) = 2%; urinary incontinence, none = 63%, mild (1/2) = 30%, moderate/severe (3/4) = 3%; urinary urgency, none = 57%, mild (1/2) = 27%, moderate/severe (3/4) = 14%; increased urinary tract infections, none = 88%, mild (1/2) = 8%, moderate/severe (3/4) = 4% |

| Couzi et al., 199531 |

Investigator-developed questionnaire |

In last 4 weeks, difficulty with bladder control |

Reported symptom 36% (n = 66 / 183) ; 55% of those reported symptom severity as mild, 22% as moderate, 23% as severe |

| Ganz et al., 200032 |

7 items adapted from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, how bothered have you been by difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying / at other times (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) |

Reported “stress urinary incontinence” at baseline = 51% ; 1 reported urinary incontinence only, 8 reported urinary incontinence and hot flashes, 27 reported urinary incontinence, hot flashes, and vaginal dryness; 1 reported urinary incontinence and vaginal dryness; at baseline urinary scale score for all women = 0.59 (0.82); effect of intervention on urinary incontinence not reported separately from menopausal symptoms |

| Ganz et al., 200234 |

Items from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, how bothered have you been by difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying / at other times (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) |

Frequency of bladder problems when laughing or crying (P = .003) and at other times (P = .007) increased significantly over time |

| Ganz et al., 200335 |

42 items from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, how bothered have you been by difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying / at other times (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) |

Approximations from graph: 25 - 34 years = 21%, 35 - 39 years = 20%, 40 - 44 years = 35%, 45 - 51 years = 38% |

| Greendale et al., 200133 |

Items from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying, difficulty with bladder control at other times; bother: 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely |

Urinary incontinence score mean = 14.8 (20.2), range = 0 to 100 |

| Gupta et al., 200643 |

Menopausal Rating Scale with 2xyxweek recall | Urinary problems (difficulty urinating, increased need to urinate, bladder incontinence); severity: 0 = mild to 4 = severe |

Reported urinary problems = 55%; reported moderate to severe symptoms = 39% |

| Land et al., 200437 |

17 items from existing instruments including the BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 7 days, bladder problems | CMF versus AC: ratio of the odds of reporting being at least’a little bit bothered by bladder problems = 4.2, 99.8 CI = 1.262, 13.767, p = .0002 |

| Leining et al., 200644 |

16 items from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, how bothered have you been by difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying / at other times (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) |

Reported loss of bladder control “slightly bothersome or more severe symptoms:” laughter 26%, other 25% |

| Morales et al., 200438 |

Leuven Menopause Form | In past 7 days, did you have frequent urination (even at night) and urgency, urine loss when coughing, sneezing and laughing: not at all; yes, with minor inconvenience; yes, with moderate inconvenience; yes, with severe inconvenience; yes, intolerable |

Endocrine therapy naive patients (n = 144) prevalence of urinary problems at baseline = 28% (n = 41);urinary problems at baseline (n = 164): tamoxifen first line patients: mild to moderate = 23%; randomized trial of tamoxifen or letrozole patients: mild to moderate = 23%; NSAI first-line patients: mild to moderate = 39%; (N)SAI previous tamoxifen patients: mild to moderate = 25%; urinary problems at 1 month (n = 163): tamoxifen first line patients: mild to moderate = 35%; randomized trial of tamoxifen or letrozole patients: mild to moderate = 28%; NSAI first-line patients: mild to moderate = 43%; (N)SAI previous tamoxifen patients: mild to moderate = 37%; urinary problems at 3 months (n = 162): tamoxifen first line patients: mild to moderate = 36%; randomized trial of tamoxifen or letrozole patients: mild to moderate = 32%; NSAI first-line patients: mild to moderate = 35%; (N)SAI previous tamoxifen patients: mild to moderate = 15%* |

| Oleske et al., 200439 |

Symptom Rating Scale (later modified for use in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project) |

In past 7 days, difficulty in bladder control |

Reported symptoms = 39%: mild 25%, moderate 16%, severe 4% |

| Schover et al., 200645 |

7 items adapted from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, how bothered have you been by difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying / at other times (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) |

Mean = .67 (1.2) at baseline |

| Stanton et al., 200541 |

42 item from BCPT Symptom Checklist |

In past 4 weeks, difficulty with bladder control (when laughing or crying); difficulty with bladder control (at other times); presence / absence = 1/0; bother: 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely |

Sample 1: 0.52 (.47 to .58); Sample 2: 0.38 (.33 to .43); Sample 3: 0.32 (.28 to .38); Sample 4: 0.40 (.31 to .50) |

Data also presented for no symptoms and severe to intolerable symptoms

BCPT = Breast Cancer Prevention Trial Symptom Checklist from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project

QOL = quality of life

BCS = breast cancer survivors

BC indicates breast cancer

CMF chemotherapy regimen = cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil

AC chemotherapy regimen = doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide

CI = confidence interval

PCS = Physical Component Summary Score; MCS indicates Mental Component Summary Score

NSAI = non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors

(N)SAI = non-steroidal and steroidal aromatase inhibitors

Among the four studies that did not use the BCPT Symptom Checklist, the approach to assessing menopausal symptoms included a study-specific 66-item survey that included vasomotor and gynecologic symptoms,31 the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endocrine Symptoms scale supplemented by study-specific questions about urinary symptoms,46 the 10-item Menopause Rating Scale,43 and the 20-item Leuven menopause form.38

Assessment of Urinary Symptoms

All of the studies assessed urinary symptoms as part of a constellation of menopausal or hormone-related symptoms. As noted, 12 studies utilized some version of the BCPT Symptom Checklist to assess the relevant symptoms. In 10 of these 12 studies, urinary symptoms were assessed with two items: “difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying” and “difficulty with bladder control at other times.” Respondents were asked to rate how bothered they were by each symptom during the past four weeks, using the 5-point Likert scale described above. The four-week time frame was used in each of the 10 studies with one exception; the study by Alfano et al.42 used the past year as the time period of interest. The two (out of 12) remaining studies that used some version of the BCPT Symptom Checklist apparently did not include both bladder control items but reportedly used “difficulty in bladder control”39 and “bladder problems”37 to assess urinary symptoms, although this is not completely clear. Difficulty in bladder control was rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not present to 3 = serious problem39 in the past seven days while “bladder problems” was rated with respect to bother associated with the symptom on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = very much in the past seven days and since the beginning of the last chemotherapy cycle.37

Urinary symptoms were assessed in various ways in the remainder of the studies. For example, Morales et al.38 defined “urinary problems” as “frequent urination (even at night) and urgency, urine loss when coughing, sneezing and laughing” and then asked respondents in a single question to rate the degree of inconvenience associated with these urinary problems during the past seven days. Chin et al.46 used four questions specific to dysuria, urinary incontinence, urgency, and increased frequency of urinary tract infections. Respondents rated how true a statement about each of these symptoms had been for them in the past 7 days on a 5-point Likert scale.

Prevalence and Severity of Urinary Symptoms

Ten of the 16 studies reported data related to the prevalence of urinary symptoms. In general, the rate of women reporting any type of urinary symptom ranged from a low of 12% reporting burning or pain on micturition in a study of women receiving endocrine therapy for early stage or metastatic breast cancer46 to a high of 58% reporting difficulty with bladder control at other times in a study of the psychometric properties of a BCPT-derived checklist for measuring hormone-related symptoms in breast cancer survivors.42 Across those studies assessing bladder control using items from the BCPT Symptom Checklist,31, 32, 36, 39, 40, 42, 44 a mean of 37% reported difficulty with bladder control either in general, when laughing or crying or at other times. In two studies,38, 43 a mean of 34% reported “urinary problems.”

Nine studies reported data related to the perceived severity of urinary symptoms. The method of reporting these data, and therefore, the information provided with respect to symptom severity was quite variable. In three of these studies41, 42, 45 data were reported as mean scores on the BCPT 5-point Likert scale of bother associated with symptoms. For example, in the study by Alfano et al.,42 that was designed to evaluate the psychometric properties of a 16-item version of the BCPT Symptom Checklist, the mean severity score for women reporting difficulty with bladder control while laughing or crying was 1.8 + 0.9. This score corresponds most closely to “somewhat” bothersome on the BCPT 5-point Likert scale of bother. In a study to identify particular problem areas for women with breast cancer, Avis et al.36 reported the percent of women in every category of bother on the 5-point Likert scales for each bladder control question; 15.4% rated difficulty with bladder control while laughing or crying as at least somewhat bothersome while 11.9% rated difficulty with bladder control at other times as at least somewhat bothersome. In five studies,31, 38, 39, 43, 46 perceived severity was reported as the percent of patients reporting some combination of no symptoms, mild, moderate, andsevere symptoms. For example, in the study by Chin et al.,46 to assess the prevalence and severity of symptoms of urogenital atrophy, 57% reported no urinary urgency, 27% reported mild urinary urgency, and 14% reported moderate/severe symptoms. In a similar study by Couzi et al.,31 among those reporting difficulty with bladder control, 55% reported symptom severity as mild, 22% as moderate, and 23% as severe.

Relationship of Urinary Symptoms to Treatment and Quality of Life

Two studies examined the effects of adjuvant therapy with surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy on urinary symptoms. In the study by Land et al.37women who received CMF were approximately four times more likely to be bothered by bladder problems during and immediately after treatment than women who received AC. Conversely, Alfano et al.42 reported that neither receipt of chemotherapy nor type of surgery were predictive of bladder control problems in the post-treatment period. As noted previously, the primary aim of two studies38, 46 was to examine the effects of endocrine therapy for breast cancer. In a longitudinal study of women with breast cancer about to start endocrine therapy, Morales et al.38 found no significant changes in urinary problems from baseline to one and three months of therapy with first-line tamoxifen or non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors. The Chin et al.46 study likewise included only women currently on endocrine therapy so no comparisons with a control group were possible, nor were comparisons made between types of endocrine therapy used. Four other studies41-44 included an examination of the effect of endocrine treatment on urinary symptoms in their analyses with mixed results. In the study by Stanton et al.,41 women currently taking tamoxifen reported significantly more bladder control problems than nonusers of tamoxifen. Conversely, three studies42-44 found no difference in urinary symptoms between current tamoxifen users and nonusers. Taken together, these results suggest the effects of endocrine therapy on urinary symptoms are not yet known.

Finally, four studies32, 33, 41, 43 examined the relationship of urinary symptoms to quality of life, including sexuality,33, 43 after a breast cancer diagnosis. Less vitality, worse physical quality of life,41, 43 worse social life,43 and worse overall quality of life43 were significantly associated with more urinary symptoms in the post-treatment period. With respect to sexuality, more urinary incontinence33 and worse urinary problems43 were significantly associated with adverse effects on sexuality in the post-treatment period.

Discussion

We identified 16 studies published between 1990 and June 2010 that examined urinary symptoms as part of the constellation of menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer. Studies varied widely with respect to study purpose, design, and the nature and size of the samples included. There was less variation in terms of how urinary symptoms were defined and assessed. In general, this reflects the state of the science related to urinary symptom research in women in the general population wherein such variability makes evaluating existing findings and estimating prevalence more difficult.48, 49 Nevertheless, most, but not all of the studies we identified report data on the prevalence of urinary symptoms. A high of 58% of women reported difficulty with bladder control. On average, using items from the BCPT Symptom Checklist,47 a mean of 37% reported difficulty with bladder control when laughing or crying or other times. Similarly, 34% reported “urinary problems.” More than half of the studies report data related to severity. All points along a continuum of mild, moderate and severe were represented. Although in many studies the largest percentage of women rated their symptoms as mild, as many as 23% of women rated their symptoms as severe. Treatments commonly associated with menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer include chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. In our review, relatively few studies examined the relationship of specific cancer treatments to urinary symptoms. Among these studies results are mixed. The relationship of urinary symptoms to quality of life was relatively clearer, with results suggesting that symptoms adversely affect the quality of life of women with a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Limitations of Existing Research

Several limitations of the existing literature should be acknowledged. As noted, relatively few studies have explored the relationship of various treatments for breast cancer to urinary symptoms as part of the constellation of menopausal symptoms. To our knowledge, no studies have made comparisons to a healthy, non-cancer control group of women; thus, it is not known whether urinary symptoms are more closely associated with breast cancer treatment. Further, only two studies have explored whether urinary symptoms may be more strongly associated with other factors such as age, obesity and race or ethnicity in women with breast cancer. Ganz et al.35 found that among breast cancer survivors, urine loss with sneezing or coughing increased in frequency with age while Morales et al.38 found that among women receiving endocrine therapy for early stage or advanced breast cancer, women with higher body mass index were more likely to report urinary problems. No studies have included a pre-treatment assessment of menopausal symptoms so it is not possible to know whether reported urinary symptoms predate a breast cancer diagnosis. There are limited data available about the course of symptoms and whether symptoms resolve or worsen over time. Only two studies34, 42 of the 16 studies we identified are longitudinal in design and the results are mixed. Studies have been limited by either a single focus on a symptom of stress urinary incontinence or a lack of specificity. To date, no study has examined the full range of urinary symptoms, including urgency, urgency incontinence, stress incontinence, dysuria or burning, pelvic pressure and frequency, recurrent urinary tract infections and dryness. This is particularly significant because the appropriate course of treatment for urinary symptoms is determined by the type and severity of symptoms.21, 22 The vast majority of studies used two questions related to bladder control from the BCPT Symptom Checklist47 to assess the prevalence and severity of urinary symptoms. In the remainder of the studies, individual questions about select urinary symptoms were used or women were asked to reflect on a short list of urinary symptoms and respond to a single question related to severity or inconvenience. To date, no studies have used validated measures specifically designed to assess urinary symptoms or urologic condition-specific quality of life measures as recommended by the International Consultation on Incontinence.50 Finally, although research in women in the general population has consistently demonstrated that urinary symptoms adversely affect women’s quality of life,18-20 there are limited data available about the effect of urinary symptoms on quality of life after breast cancer; existing data suggest that symptoms do have a negative effect on women’s quality of life after breast cancer, however.

Conclusions

Our systematic review of the literature suggests that urinary symptoms are prevalent among women diagnosed and treated for breast cancer and that these symptoms tend to be mild to moderate in severity. In women in the general population, conservative first-line treatment of mild to moderate urinary symptoms includes behavioral strategies such as self-monitoring, lifestyle changes,24, 51 and pelvic floor muscle exercises.52 Such treatment typically results in significant improvement and minimal adverse outcomes. More severe symptoms may require more invasive interventions and pharmacologic management. Our findings support the notion that clinicians should screen for urinary symptoms in women with breast cancer and offer treatment recommendations or make referrals as appropriate. Our review also highlights the need for additional research assessing the natural history of urinary symptoms using consensus definitions,53 their relation to breast cancer treatments and their impact on women’s quality of life using validated, recommended assessment approaches in diverse populations. Results of such studies would serve to inform the development of interventions to ameliorate the effects of urinary symptoms in survivorship.

Condensed Abstract.

A systematic review of studies published between 1990 and 2010 was conducted to describe the prevalence and severity of urinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Results show that urinary symptoms are prevalent among women diagnosed and treated for breast cancer and tend to be mild to moderate in severity.

Acknowledgments

Supported by American Cancer Society Grant MRSG-06-082-01-CPPB and National Cancer Institute Grant 1R03CA142061-01.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2007-2008. American Cancer Society; Altanta, GA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2008. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine and National Research . From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. National Academy of Sciences; Washington, D.C.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganz PA. Menopause and breast cancer: Symptoms, late effects, and their management. Seminars in Oncology. 2001;28:274–83. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lester JL, Bernhard LA. Urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(6):693–8. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.693-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PF, Remington PL, Trentham-Dietz A, Allen CI, Newcomb PA. Prevalence and treatment of menopausal symptoms among breast cancer survivors. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2002;23:501–09. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith IE, Dosett M. Aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:2431–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trinkaus M, Chin A, Wolfman W, Simmons C, Clemons M. Should urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors be treated with topical estrogens? The Oncologist. 2008;13:222–31. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iosif CS, Bekassy Z. Prevalence of genito-urinary symptoms in the late menopause. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63:257–60. doi: 10.3109/00016348409155509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaffer J, Fantl JA. Urogenital effects of the menopause. Baillieres Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;10:401–17. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(96)80022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Voorhis BJ. Genitourinary symptoms in the menopausal transition. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12B):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iosif CS, Batra S, Edk A, Astedt B. Estrogen receptors in the human female lower urinary tract. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;141:817–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saez S, Martin PM. Evidence of estrogen receptors in the trigone area of human urinary bladder. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;15:317–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(81)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batra SC, Iosif CS. Progesterone receptors in the female lower urinary tract. Journal of Urology. 1984;138:1301–04. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dew JE, Wren BG, Eden JA. A cohort study of topical vaginal estrogen therapy in women previously treated for breast cancer. Climacteric. 2003;6:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Tannenbaum C, Thorpe KE, Straus SE. What type of urinary incontinence does this woman have? JAMA. 2008;299:1446–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.12.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyman JF, Harkins SW, Choi SC, Taylor JR, Fantl JA. Psychosocial impact of urinary incontinence in women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;70:378–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margalith I, Gillon G, Gordon D. Urinary incontinence in women under 65: quality of life, stress related to incontinence and patterns of seeking health care. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(8):1381–90. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000040794.77438.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ragins AI, Shan J, Thom DH, Subak LL, Brown JS, Van Den Eeden SK. Effects of urinary incontinence, comorbidity and race on quality of life outcomes in women. The Journal of Urology. 2008;179:651–55. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Vaart CH, de Leeuw JRJ, Roovers JWR, Heintz APM. Measuring health-related quality of life in women with urogenital dysfunction: The Urogenital Distress Inventory and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Revisited. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2003;22:97–104. doi: 10.1002/nau.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paick J, Kim SW, Oh S, Ku JH. A generic health-related quality of life instrument, the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36, in women with urinary incontinence. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;130:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dougherty MC, Dwyer JW, Pendergast JF, Boyington AR, Tomlinson BU, Coward RT, et al. A randomized trial of behavioral management for continence with older rural women. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(1):3–13. doi: 10.1002/nur.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyman JF. Treatment of urinary incontinence in men and older women: The evidence shows the efficacy of a variety of techniques. American Journal of Nursing. 2003;(Suppl):26–35. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200303001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyington AR, Dougherty MC, Phetrasuwan S. Effectiveness of a computer-based system to deliver a continence health promotion intervention. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 2005;32:246–54. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, Wyman J, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: randomized, controlled trials of nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in women. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:459–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dugan E, Roberts C, Cohen S, et al. Why older community-dwelling adults do not discuss urinary incontinence with their primary care physicians. American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49:462–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagglund D, Walker-Engstrom ML, Larsson G, Leppert J. Quality of life and seeking help in women with urinary incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(11):1051–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch LH. Help-seeking behaviors of women with urinary incontinence: an integrative literature review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2006;51(6):e39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melville JL, Wagner LE, Fan M, Katon WJ, Newton KM. Women’s perceptions about the etiology of urinary incontinence. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17:1093–98. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Couzi RJ, Helzlsouer KJ, Fetting JH. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms among women with a history of breast cancer and attitudes toward estrogen replacement therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(11):2737–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.11.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Zibecchi L, Kahn B, Belin TR. Managing menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(13):1054–64. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greendale GA, Petersen L, Zibecchi L, Ganz PA. Factors related to sexual function in postmenopausal women with a history of breast cancer. Menopause. 2001;8(2):111–9. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(1):39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4184–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Psychosocial problems among younger women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(5):295–308. doi: 10.1002/pon.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Land SR, Kopec JA, Yothers G, Anderson S, Day R, Tang G, et al. Health-related quality of life in axillary node-negative, estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer patients undergoing AC versus CMF chemotherapy: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-23. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;86(2):153–64. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000032983.87966.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morales L, Neven P, Timmerman D, Christiaens MR, Vergote I, Van Limbergen E, et al. Acute effects of tamoxifen and third-generation aromatase inhibitors on menopausal symptoms of breast cancer patients. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15(8):753–60. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oleske DM, Cobleigh MA, Phillips M, Nachman KL. Determination of factors associated with hospitalization in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(6):1081–8. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.1081-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3322–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanton AL, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA. The BCPT symptom scales: A measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with or at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(6):448–56. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, Reeve BB, Bowen DJ, Baumgartner KB, et al. Psychometric properties of a tool for measuring hormone-related symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(11):985–1000. doi: 10.1002/pon.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta P, Sturdee DW, Palin SL, Majumder K, Fear R, Marshall T, et al. Menopausal symptoms in women treated for breast cancer: the prevalence and severity of symptoms and their perceived effects on quality of life. Climacteric. 2006;9(1):49–58. doi: 10.1080/13697130500487224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leining MG, Gelber S, Rosenberg R, Przypyszny M, Winer EP, Partridge AH. Menopausal-type symptoms in young breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(12):1777–82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schover LR, Jenkins R, Sui D, Adams JH, Marion MS, Jackson KE. Randomized trial of peer counseling on reproductive health in African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(10):1620–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chin SN, Trinkaus M, Simmons C, Flynn C, Dranitsaris G, Bolivar R, et al. Prevalence and severity of urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women receiving endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(2):108–17. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2009.n.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganz PA, Day R, Wre JE, Jr, Redmond C, Fisher B. Baseline quality of life assessment in the National Surgical Adjuvant Brest and Bowel Project Brest Cancer Prevention Trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87:1372–82. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.18.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landefeld CS, Bowers BJ, Feld AD, Hartmann KE, Hoffman E, Ingber MJ, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: prevention of fecal and urinary incontinence in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(6):449–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altman D, Lapitan MC, Nelson R, Sillen U, Thom D. Epidemiology of urinary (UI) and faecal (FI) incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) In: Abrams PC, L., Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence: Proceedings from the 4th International Consultation on Incontinence. Health Publication Ltd; Plymouth, MA: 2009. pp. 35–111. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staskin D, Kelleher C, Bosch R, Coyne K, Cotterill N, Emmanuel A, et al. Patient-oriented assessment. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence: Proceedings from the 4th International Consultation on Incontinence. Health Publications Ltd.; Paris, France: 2009. pp. 363–412. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kincade JE, Dougherty MC, Carlson JR, Hunter GS, Busby-Whitehead J. Randomized clinical trial of efficacy of self-monitoring techniques to treat urinary incontinence in women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26(4):507–11. doi: 10.1002/nau.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub2. Art No: CD005654. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA/International Incontinence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2009;29:4–20. doi: 10.1002/nau.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]