Abstract

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease. Epidemiological and treatment studies suggest that fungi play a part in the pathogenesis. The aim of this work was to study the effect of fungal cell wall agents (FCWA) on the in vitro secretion of cytokines from peripheral blood monocytes from subjects with sarcoidosis and relate the results to fungal exposure at home and clinical findings. Subjects with sarcoidosis (n = 22) and controls (n = 20) participated. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with soluble or particulate β-glucan (S-glucan, P-glucan), chitin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), whereafter tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10 and IL-12 were measured. The severity of sarcoidosis was determined using a chest X-ray-based score. Serum cytokines (IL-2R, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12) were determined. To measure domestic fungal exposure, air in the bedrooms was sampled on filters. N-acetylhexosaminidase (NAHA) on the filters was measured as a marker of fungal cell biomass. The induced secretion of cytokines was higher from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from subjects with sarcoidosis. P-glucan was more potent than S-glucan inducing a secretion. Chitin had a small effect. Among subjects with sarcoidosis there was a significant relation between the spontaneous PBMC production of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 and the NAHA levels at home. The P-glucan induced secretion of IL-12 was related to the duration of symptoms at the time of diagnosis. Their X-ray scores were related to an increased secretion of cytokines after stimulation with LPS or P-glucan. Subjects with sarcoidosis have a higher reactivity to FCWA in vitro and to home exposure. The influence of FCWA on inflammatory cells and their interference with the inflammatory defense mechanisms in terms of cytokine secretion could be important factors for the development of sarcoidosis.

Keywords: chitin, endotoxin, fungi, sarcoidosis, β-glucan

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease, often leading to granuloma formation. The cytokine inflammatory response is characterized by a T helper type 1 (Th1)-directed inflammation with alterations in cytokine secretion and abnormal lymphocyte characteristics [1–3]. Th1 and Th2 chemokines are involved and the amounts of interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-12 are elevated in serum and in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) [4–7]. In advanced stages fibrosis may develop.

Although there is no general agreement on the causative agent, data from recent studies suggest that moulds (fungi) may be important. Data from epidemiological studies demonstrate an increased risk for those who have occupations with fungal exposure or stay in buildings with mould problems [8,9]. High levels of fungal exposure have been found in homes of subjects with sarcoidosis, particularly among those with recurrent disease [10]. In studies where sarcoidosis was treated with anti-fungal medication, the effect was found to be better than after corticosteroid treatment in most patients [11,12].

It is has been suggested that the mechanism behind the development of sarcoidosis after fungal exposure in not an infection but an immunological reaction to some agent(s) in the fungi [13]. If this were so, one would expect that fungi would induce an inflammation with a secretion of cytokines similar to the one found in sarcoidosis. Previous studies have demonstrated that a major agent in the fungal cell wall –β-glucan – can induce different changes in the immune system and granulomas, depending on dose and means of administration (review in [14]). Chitin is another fungal cell wall agent (FCWA) that can induce immune changes, dependent upon its size [15,16]. In an in vitro study on the reactivity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy subjects, particulate β-glucan was found to induce the secretion of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 [17].

The purpose of the present investigation was to evaluate if the FCWA-induced secretion of some cytokines known previously to be related to sarcoidosis (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12) was different between subjects with sarcoidosis and controls, and if the secretion was related to the domestic exposure to fungi and to clinical findings among subjects with sarcoidosis.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study comprises newly diagnosed cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis (n = 22, average age 44·7 years, 12 females) recruited at the Clinic of Respiratory Diseases and Allergy at the University Medical Centre, Ljubljana, Slovenia and diagnosed using the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society (ERS/ATS) criteria [18]. Stage II was present in 15 and stage III in seven of the subjects. The average duration of symptoms until final diagnosis and treatment was 5·5 months [median 4·5, standard deviation (s.d.) 3–6]. Extra-pulmonary manifestations were present in seven patients. BAL index mean was 7·5 (s.d. 3·0), spirometry vital capacity (VC) 93·8 (s.d. 11) and carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) 87% (s.d. 12). There were no differences in immunoglobulin (Ig0A, IgM and IgG antibodies against Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans between controls and sarcoidosis patients. Subjects without pulmonary disease or any respiratory symptoms (n = 20, age 39·9, ±1·8, 13 females) served as controls. All subjects were non-smokers.

The study was approved by the Governmental Medical Ethics Committee, Ljubljana (198/05/04) and written, informed consent was obtained.

Clinical assessments

The clinical stage of the disease was determined using chest X-rays of the lung of subjects with sarcoidosis. A grading scheme for the presence of granulomas was used as described previously [11,12,19]. The X-rays were read by two experienced radiologists, unaware of the status of the patient, grading granulomas according to a numerical score (0–4), judging size and extension of the infiltrates (0 = normal, 1 = c. 25% of the lung field involved, 2 = up to 50%, 3 = up to 75% and 4 = virtually the whole lung field involved). Repeat evaluations on two successive occasions showed only minor deviations in the classification. Among the subjects with sarcoidosis there were five with X-ray score 1, 13 with score 2 and four with score 3. For ethical reasons, chest X-rays were not performed on controls but were given the value 0. Serum samples were taken and the amounts of TNF-α, IL-2R, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 were determined using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Milenyi Biotec, Heidelberg, Germany and Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA).

In vitro cell assays

For the in vitro assay PBMC were incubated with different FCWA or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), as reported previously [17]. Briefly, PBMC were isolated from venous blood samples by density gradient centrifugation and incubated in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mm l-glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated human serum. The cells (1 × 106) were plated in 24-well culture plates with medium alone, with soluble or particulate β-glucan (S-glucan, P-glucan), chitin (all 200 µg/ml) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 ng/ml). The cytokines were measured in the cell culture supernatants; TNF-α after 4 h incubation at 37°C and IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 after 18 h incubation at 37°C using commercial ELISA kits (Milenyi Biotec Thermo Scientific). The cytokine responses were measured without (spontaneous) and after stimulation and the values of the spontaneous secretion were deducted from the challenge values to allow for comparison with other, similar studies (e.g. [20]). Counting of white blood cells showed only minor differences in the monocyte/lymphocyte ratio between controls and subjects with sarcoidosis.

Exposure determination

The participants were supplied with a pump and filter holders preloaded with cellulose acetate filters (Mixed Cellulose Esters, 25 mm PCM Casettes, 0·8 µm pore size; Zeflon International Inc., Ocala, FL, USA). The subjects turned on the pump and sampling was performed for about 4 h. The exact volume sampled was read from a volume meter attached to the pump and was usually about 2·5 m3.

The filters were analysed for their content of N-acetylhexosaminidase (NAHA) using an enzyme technique [10,21]. One ml of a fluorogenic enzyme substrate (4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide; Mycometer A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) was added to the filter, followed by 2 ml of a developer after an incubation period of around 30 min, determined by the room temperature. The liquid was sucked out through the filter and placed in a cuvette. The fluorescence in the cuvette was read in a fluorometer (Picofluor; Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). To decrease the variance induced by methodological variations in the analysis technique, the fluorescence values were divided by 10 and rounded off to the nearest whole number to express NAHA activity in units (NAHA U/m3).

Statistical analysis

Values in the different groups were calculated using spss version 17–W7 and expressed as mean and standard error of the mean. Differences between groups were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney test and the intercorrelations assessed using Spearman's-test. A P-value of < 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Spontaneous cytokine secretion

The spontaneous secretion of different cytokines from PBMC is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Spontaneous secretion of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10 and IL-12 (pg/ml) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells

| n | TNF-α | IL-6 | IL-10 | IL-12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 20 | 2·5 (0·5) | 79 (19) | 0·4 (0·1) | 2 (1) |

| Sarcoidosis | 22 | 12 (0·2) | 208 (52) | 1 (0·3) | 5 (1) |

| p C/S | 0·002 | n.s. | n.s. | 0·026 |

Mean ± standard error of the mean. C: control subjects; S: subjects with sarcoidosis; n.s.: not significant.

The spontaneous secretion of all cytokines was higher from PBMC from subjects with sarcoidosis with significant differences for TNF-α and IL-12.

Cytokine secretion after FCWA challenge

Table 2 reports the secretion of cytokines after incubation with different FCWA and LPS.

Table 2.

Secretion of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10 and IL-12 (pg/ml) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells after incubation with S-glucan, P-glucan, chitin and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

| S-glucan | P-glucan | Chitin | LPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | ||||

| C | 104 (19) | 1897 (112) | 16 (2) | 902 (77) |

| S | 255 (41) | 3173 (293) | 7 (4) | 1584 (178) |

| pC/S | 0·010 | 0·001 | n.s. | 0·004 |

| IL-6 | ||||

| C | 672 (214) | 6505 (958) | 435 (91) | 6758 (1031) |

| S | 1065 (314) | 10730 (768) | 504 (101) | 9837 (948) |

| pC/S | n.s. | 0·001 | n.s. | 0·013 |

| IL-10 | ||||

| C | 12 (4) | 235 (34) | 5 (1) | 170 (22) |

| S | 13 (5) | 413 (32) | 8 (1) | 333 (36) |

| pC/S | n.s. | 0·001 | n.s. | < 0·001 |

| IL-12 | ||||

| C | 17 (5) | 925 (150) | 1 (1) | 307 (41) |

| S | 27 (7) | 2304 (309) | 1 (2) | 1024 (155) |

| pC/S | n.s. | 0·002 | n.s. | < 0·001 |

Mean ± standard error of the mean. C: control subjects (n = 20); S: subjects with sarcodosis (n = 22); n.s.: not significant.

After stimulation with S-glucan the secretion of TNF-α was significantly higher among subjects with sarcoidosis, but there were no differences for the other cytokines. Stimulation with P-glucan caused a high secretion of all cytokines, which was significantly higher among subjects with sarcoidosis. Chitin was a comparatively weak inducer of cytokines in both groups except for IL-6, and no differences were found between controls and sarcoidosis. After stimulation with LPS there was an increase in the secretion of all cytokines with significantly higher levels from PBMC from subjects with sarcoidosis.

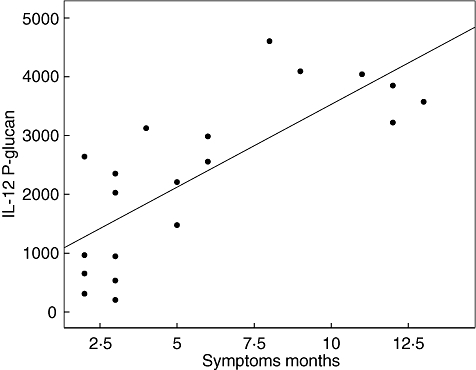

The secretion of cytokines after PBMC challenge was related to the number of months that the patient had experienced symptoms before performing the PBCM challenge. There were significant relationships between the IL-12 secretion induced by P-glucan, chitin and LPS (correlation coefficient 0·783, P < 0·001, 0·656, P = 0·002 and 0·835, P < 0·001, respectively) but not for S-glucan. There was also a relation between the duration of the symptoms and the spontaneous secretion of TNF-α (0·323, P = 0·015) and the LPS-induced secretion of TNF-α (0·490, P = 0·020). The relationship between duration of symptoms and the P-glucan-induced secretion of IL-12 is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Relation between P-glucan-induced secretion of interleukin-12 from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and duration of symptoms. Corrected coefficient 0·783, P < 0·001.

Cytokine secretion and serum cytokines

The serum values of cytokines were higher among subjects with sarcoidosis (data not shown) with significant differences for IL-6 and IL-12 (P < 0·001 and 0·003, respectively).

The significant relationships between the in vitro production of cytokines and serum levels of IL-2R and IL-12 in the whole material are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationships between glucan-induced secretion of cytokines from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and serum levels of interleukin (IL)-2R and IL-12

| Serum cytokines | IL-2R | IL-12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine and stimulant | P | Corr. coeff. | P | Corr. coeff. |

| TNF-α | ||||

| S-glucan | 0·001 | 0·525 | 0·039 | 0·327 |

| P-glucan | < 0·001 | 0·608 | 0·015 | 0·383 |

| IL-6 | ||||

| P-glucan | 0·049 | 0·354 | 0·003 | 0·478 |

| IL-10 | ||||

| P-glucan | n.s. | 0·276 | 0·036 | 0·350 |

| IL-12 | ||||

| P-glucan | < 0·001 | 0·552 | 0·027 | 0·359 |

TNF: tumour necrosis factor; n.s.: not significant.

The serum level of IL-12 was related consistently to the secretion of different cytokines induced by P-glucan. The relationship to IL-2R was less marked. There was also a relation between the P-glucan-stimulated release of IL-12 and the serum level of TNF-α. There were no significant relationships for the chitin-induced secretions and serum cytokines.

Fungal exposure at home

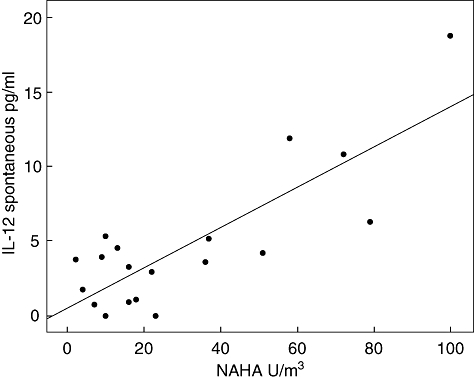

The average level of NAHA in the homes of controls was 12·9 (1·5) U/m3 and among subjects with sarcoidosis 30·9 (6·1) (P = 0·046). Among controls there were no relations between NAHA levels at home and the in vitro secretion of different cytokines. In subjects with sarcoidosis there were significant relationships between NAHA levels and the spontaneous secretion of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 (correlation coefficient 0·507, P = 0·027, correlation coefficient 0·725, P < 0·001 and correlation coefficient 0·567, P = 0·011, respectively). There was also an inverse relationship between the chitin-induced secretion of IL-12 and the NAHA levels in the homes and between NAHA and the LPS induced secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 (correlation coefficient 0·621, P = 0·005 and correlation coefficient 0·457, P = 0·049, respectively). Figure 2 illustrates the relation between the amount of NAHA in the homes of subjects with sarcoidosis and the spontaneous secretion of IL-12.

Fig. 2.

Relation between NAHA levels in homes of subjects with sarcoidosis and spontaneous secretion of interleukin-12 from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Corrected coefficient 0·567, P = 0·011.

Subjects with a high fungal exposure at home also had a higher spontaneous secretion of IL-12 from their PBMC.

PBMC secretion in relation to chest X-ray score

The relations between chest X-ray scores and the secretion of all cytokines after stimulation with P-glucan and LPS for the whole material are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Relationships between chest X-ray scores and secretion of different cytokines from peripheral blood mononuclear cells after stimulation with P-glucan or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

| Cytokine and stimulant | P | Corr. coeff. |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | ||

| LPS | 0·019 | 0·361 |

| P-glucan | 0·004 | 0·410 |

| IL-6 | ||

| LPS | 0·019 | 0·369 |

| P-glucan | < 0·001 | 0·586 |

| IL-10 | ||

| LPS | 0·002 | 0·483 |

| P-glucan | < 0·001 | 0·542 |

| IL-12 | ||

| LPS | 0·003 | 0·455 |

| P-glucan | 0·002 | 0·470 |

IL: interleukin; TNF: tumour necrosis factor.

There were significant relationships between chest X-ray scores and the secretion of all cytokines after stimulation with LPS or P-glucan.

Discussion

The major findings from the study stem from the relation between reactions induced by FCWA in vitro, in vivo and the environment. The FCWA and LPS induced a secretion of different cytokines from PBMC in vitro that was stronger among subjects with sarcoidosis. There was a relation between fungal exposure at home and the spontaneous PBMC secretion of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 among subjects with sarcoidosis. A significant relationship was observed between disease severity, measured as chest X-ray scores indicating granuloma infiltration, and the P-glucan- and LPS-induced secretion of all cytokines. There was also a positive relation between the P-glucan-induced secretion of IL-12 and the duration of symptoms.

There are some limitations to the study. The FCWA and LPS preparations used in the study were chemically well-defined compounds of bacterial and fungal origins but these are not wholly representative of the agents as present in the environment [15]. S-glucan and P-glucan were purified from Alcaligenes faecalis, but in nature β-glucan is present together with capsular materials and chitin. The chitin preparation used was a de-acetylated form of chitin. LPS is a chemically purified lipopolysaccharide from Gram-negative bacteria, whereas the endotoxin present in nature also comprises proteins and sugars from the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria [22]. In view of these differences between the substances used in the PBMC stimulation experiments and natural agents, caution should be applied in the interpretation of the in vitro findings and their relevance for clinical conditions. If, on the other hand, observations from exposures and cytokines in vivo parallel the in vitro results, the validity of the latter is supported.

The in vitro method used also has some limits in terms of interpretation. A potential shortcoming is the lack of definition of different cell types. Due to the chronic inflammation subjects with sarcoidosis might have a different cell population particularly regarding lymphocytes, both in numbers and subtypes. Thus differences in cytokine production between patients with sarcoidosis and controls could be due to different proportions of responsive cells in the PBMC isolates. PBMC consist, however, mainly of monocytes and lymphocytes and the proportion reflects the monocyte/lymphocyte proportion in white blood cells. These were counted in all our sarcoidosis patients and only minor changes were present in the mono/lymph ratio compared to controls. From a clinical viewpoint, the presence of an inflammation is the most important issue for the patient. Whether or not this is due to a different distribution of cells is interesting from a mechanistic point of view, but not for the patient. The conclusion that subjects with sarcoidosis react more to FCWA and to the fungal exposure at home is thus a relevant finding, irrespective of the underlying mechanism.

The results confirm findings from many previous investigations where FCWA were found to have important immunomodulating characteristics [14]. The FCWA used here had different effects on the secretion of cytokines from PBMC. P-glucan induced a high secretion of all cytokines. This agrees with the results from an experimental model where rats were exposed by intratracheal instillations to particulate β-glucan (around 2 mg/kg body weight) [23]. There were dose-related increases in a variety of indicators of pulmonary inflammation, such as number of polymorphonuclear leucocytes, amounts of albumin and lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) in the bronchi and nitric oxide production of alveolar macrophages. Contradictory results were reported from an acute inhalation exposure in guinea-pigs to non-soluble curdlan, schizophyllan and zymosan (300 µg/m3 for 40 min) [24]. There was no effect on the number of neutrophils in the airways, but a tendency to a decreased number of macrophages and lymphocytes. The discrepancy between the studies is related probably to the differences in dose levels, where P-glucan in low levels does not induce an inflammatory response. Another reason might be interspecies differences in lung macrophage function [25]. In the present in vitro experiments with PBMC, the dose level per cell was very high compared to environmental exposures.

P-glucan caused a large increase in the secretion of IL-6, which was higher among subjects with sarcoidosis. This cytokine is a potent inducer of a general inflammatory response, involving several cytokines such as IL-17 which has been related to granuloma formation. Secretion of the anti-inflammatory IL-10, as seen after the stimulation with P-glucan and LPS, will inhibit macrophages and the differentiation of Th2 cells into Th1 effector cells [26]. The secretion was higher among subjects with sarcoidosis, which is in agreement with previous studies where the secretion of IL-10 from alveolar macrophages was higher among subjects with sarcoidosis compared to controls [27,28]. IL-10 has important anti-inflammatory properties and also supresses granuloma formation [29].

S-glucan was a moderate inducer of cytokines from PBMC. In previous experiments an intratracheal instillation of a soluble β-glucan from C. albicans (25–100 ug/animal) was found to induce neutrophil and eosinophil inflammation with increased local expression of a variety of inflammatory cytokines [IL-1β, IL-6, macrophage proteins and regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES)][30]. This suggests that S-glucan and P-glucan trigger different mechanisms for cytokine secretion from PBMC.

The relation between the P-glucan-induced release of all the cytokines measured and serum levels of IL-2R and IL-12 connects the PBMC reactivity with two major inflammatory markers of sarcoidosis [6]. The ability of PBMC to secrete IL-12 after stimulation with P-glucan also related to the duration of the disease, reflecting the increasing inflammatory changes developing in sarcoidosis and paralleling the relation between domestic exposure to NAHA and spontaneous secretion of IL-12. This suggests that IL-12 plays an important role in the inflammatory reactions involved in sarcoidosis, as suggested previously [6], and that it is related to the level and duration of fungal exposure.

Among subjects with sarcoidosis, those living in homes with higher NAHA values had a higher spontaneous as well as LPS-induced secretion of IL-6 and IL-10. This agrees in principle with findings from a study on farmers, where the blood cell secretion of IL-10 was related to their occupational endotoxin exposure [20]. The chest X-ray score was related to the LPS- and P-glucan-induced secretion of all cytokines. This probably reflects the chronic inflammatory condition present in sarcoidosis. It could be of interest to explore the usefulness of this kind of in vitro challenge for monitoring sarcoidosis and the effects of treatment.

A synthesis of the different findings regarding effects of FCWA and the mechanisms known to be involved in sarcoidosis demonstrates several similarities. FCWA are known to induce an inflammatory response, chiefly through the Dectin-1 receptor. There was an induction of TNF-α secretion as well as IL-10, which is similar to the findings in sarcoidosis. The relationships between home exposure and cytokine secretion reflect a more intensive inflammation when exposed to the causative agent. The inverse relationship between the FCWA exposure at home and the capacity to secrete cytokines reflects the exhaustion of the system, as evidenced by the higher spontaneous secretion at higher exposure levels. The emphasis towards Th1-derived reactions, particularly TNF-α, relates to the lower incidence of atopy among subjects with sarcoidosis [31].

Conclusions

The results demonstrate that cellular and systemic reactions related to fungal or FCWA exposure are stronger among subjects with sarcoidosis. The augmented inflammatory response to FCWA among subjects with sarcoidosis and the relation to domestic fungal exposure relate to the inflammatory nature of the disease. The FCWA-induced effects on the cytokine secretion suggest an influence on anti-inflammatory defence mechanisms that might be important in the development of sarcoidosis. Further research on the interaction between FCWA and cell reactivity is warranted, with emphasis on clinical and preventive aspects.

Disclosure

None of the authors have any disclosures to make.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from the Slovenian research agency, programme number P3-0083-0381, a grant from the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology of the Republic of Slovenia (doctoral fellowship), and the University Medical Center Ljubljana, Terciar Research programme number 70199.

References

- 1.Hill TA, Lightman S, Pantelidis P, Abdallah A, Spagnolo P, du Bois RM. Intracellular cytokine profiles and T cell activation in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Cytokine. 2008;42:289–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zissel G, Prasse A, Müller-Querheim J. Immunologic response of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:390–403. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerke A, Hunnunghake G. The immunology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:379–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.S-i N, Miyazaki E, Ando M, et al. Circulating levels of both Th1 and Th2 chemokines are elevated in patients with sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2008;102:239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mroz RM, Korniluk M, Stasiak-Barmuta A, Chyczewska E. Increased levels of interleukin-12 and interleukin-18 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl 6):507–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hata M, Sugisaki K, Miyazaki E, Kumamoto T, Tsuda T. Circulating IL-12p40 is increased in patients with sarcoidosis; correlation with clinical markers. Intern Med. 2007;46:1387–93. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moller DR, Forman JD, Liu MC, et al. Enhanced expression of IL-12 associated with Th1 cytokine profiles in active pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Immunol. 1996;156:4952–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, the ACCESS Research Group A case–control etiological study of sarcoidosis – environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-249OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laney AS, Cragin LA, Blevins LZ, et al. Sarcoidosis, asthma, and asthma-like symptoms among occupants of a historically water-damaged office building. Indoor Air. 2009;19:83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2008.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terčelj M, Salobir B, Rylander R. Airborne enzyme in homes of patients with sarcoidosis. Env Health. 2011;10:8–13. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terčelj M, Rott T, Rylander R. Antifungal treatment in sarcoidosis – a pilot intervention trial. Resp Med. 2007;101:774–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terčelj M, Salobir B, Rylander R. Antifungal medication is efficient in treatment of sarcoidosis. Ther Adv Resp Dis. 2011;5:157–62. doi: 10.1177/1753465811401648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terčelj M, Salobir B, Rylander R. Microbial antigen treatment in sarcoidosis – a new paradigm? Med Hypotheses. 2008;70:831–4. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rylander R. Organic dust induced pulmonary disease – the role of mould derived β-glucan. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2010;17:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzarelli RAA. Chitins and chitosans as immunoadjuvants and non-allergic drug carriers. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:292–312. doi: 10.3390/md8020292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon HJ, Moon ME, Park HS, Im SY, Kim YH. Chitosan oligosaccharide (COS) inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory effects in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:954–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stopinšek S, Ihan A, Wraber B, et al. Fungal cell wall agents suppress the innate inflammatory cytokine responses of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells challenged with lipopolysaccharide in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;8:939–47. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736–55. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terčelj M, Salobir B, Wraber B, Simcic S, Rylander R. Chitotriosidase activity in sarcoidosis and some other pulmonary diseases. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2009;69:575–8. doi: 10.1080/00365510902829362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smit LAM, Heederik D, Doekes G, Krop EJM, Rijkers GT, Wouters IM. Ex vivo cytokine release reflects sensitivity to occupational endotoxin exposure. Eur J Respir Dis. 2009;34:795–802. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00161908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rylander R, Reeslev M, Hulander T. Airborne enzyme measurements to detect indoor mould exposure. J Environ Monit. 2010;12:2161–4. doi: 10.1039/c0em00336k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rylander R, Jacobs RR. Endotoxins in the environment: a criteria document. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1997;3:S1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young S-H, Robinson VA, Barger M, et al. Exposure to particulate 1-3-β-glucans induces greater pulmonary toxicity than soluble 1-3-β-glucans in rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2003;66:25–38. doi: 10.1080/15287390306462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rylander R, Fogelmark B, Ewaldsson B. Mouldy environments and toxic pneumonitis. J Toxicol Ind Health. 2008;24:177–80. doi: 10.1177/0748233708093356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holt PG, Batty JE. Alveolar macrophages V: comparative studies on the antigen presentation activity of guinea pig and rat alveolar macrophages. Immunology. 1980;14:361–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saraiva M, O'Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:170–81. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oltmanns O, Schmidt B, Hoerning S, Witt C, John M. Increased spontaneous interleukin-10 release from alveolar macrophages in active pulmonary sarcoidosis. Exp Lung Res. 2003;29:315–28. doi: 10.1080/01902140303786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bingisser R, Peich R, Zollinger A, Russi E, Frei K. Interleukin-10 secretion by alveolar macrophages and monocytes in sarcoidosis. Respiration. 2000;67:280–6. doi: 10.1159/000029511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herfarht HH, Mohanty SP, Rath HC, Tonkonogy S, Sartor RB. Interleukin 10 suppresses experimental chronic, granulomatous inflammation induced by bacterial cell wall polymers. Gut. 1996;39:836–45. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.6.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue K, Takano H, Oda T, et al. Candida soluble cell wall β-D-glucan induces lung inflammation in mice. Int J Immunopath Pharmacol. 2007;20:499–508. doi: 10.1177/039463200702000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kokturk N, Han ER, Turktas H. Atopic status in patients with sarcoidosis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]