Abstract

When engaged in a skilled behaviour such as occurs in sports, people's perceptions relate optical information to their performance. In current research we demonstrate the effects of performance on size perception in golfers. We found golfers who played better judged the hole to be bigger than golfers who did not play as well (Study 1). In follow-up laboratory experiments, participants putted on a golf mat from a location near or far from the hole then judged the size of the hole. Participants who putted from the near location perceived the hole to be bigger than participants who putted from the far location. Our results demonstrate that perception is influenced by the perceiver's current ability to act effectively in the environment.

Performance affects the perceived size of an action's target. For example, softball players who are hitting well judge the ball to be bigger than players who have more difficulty hitting (Witt & Proffitt, 2005). The notion that action-related information such as performance levels affects perception challenges many past and current theories of perception (e.g. Fodor, 1999; Pylsyln, 2005). Most theories consider perception to be an encapsulated process that is informed solely by optical information and oculo-motor adjustments. However, a growing body of research demonstrates that action abilities affect perceived size (Wesp, Cichello, Gracia, & Davis, 2004; Witt & Proffitt, 2005), distance (Proffitt, Stefanucci, Banton, & Epstein, 2003; Witt, Proffitt, & Epstein, 2004, 2005), and geographical slant (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999).

In a study on softball players (Witt & Proffitt, 2005), we found a significant correlation between batting average for the game or games played on that night and judged ball size. Players who had hit well recalled the size of the softball to be bigger than those who hit less well, thereby suggesting a relationship between perception and performance. However, a question remains as to who really sees the ball as bigger. It could be the people who are just better players, or it could be the people who played better than usual on that night. This question addresses the nature of the effects of performance on perception. These effects might be time dependent, in which case only players who are playing well at the moment will see the ball as bigger, or the effect might be quite general, in which case better players will always see the ball as bigger, independent of how they are playing at any given time.

In order to better understand the effects of performance on perception, we conducted a similar experiment with golfers. Golfers often comment on how their perception of the hole varies with performance. Anecdotal and highly exaggerated comments found in the sport's press suggest that on good days, the hole can look as big as a bucket or a basketball hoop. On bad days, the hole can look as small as a dime, an aspirin, or the inside of a Krispy Kreme donut. The optical information received by the eye is obviously the same regardless of how well golfers are playing, so do golfers really see the hole differently depending on their performance? And if so, is the effect due to their performance on that day or to their general abilities to play golf? Either way, the results would suggest that the perceived capacity to successfully perform a goal-oriented action can influence how big the target looks.

Study 1

We recruited golfers after they played a round of golf and asked them to estimate the size of the hole. We also collected information on how well they played that day, and found correlations between performance and apparent hole size.

Method

Participants

Forty-six golfers (1 female; age range 26–66, mean age = 45.9) at the Providence Golf Club in Richmond, VA agreed to participate. All gave informed consent.

Stimuli

Nine black paper circles were glued on to a piece of white poster board that was 76 cm wide and 51 cm tall with the smaller circles in the top left corner and the larger circles on the bottom right corner. The circles ranged unsystematically in size from 9 cm to 13 cm in diameter. The actual size of a golf hole is 10.8 cm.

Procedure

After playing a full round of golf, players were recruited to participate in the experiment. They signed an informed consent agreement. Then they were shown the poster board with the various circles and asked to pick the circle that they thought best corresponded to the size of the hole. Then, we collected information on their score for the course that day, their handicap, how many putts they took on the 18th green, and how many strokes they took on the 18th hole. For each of these measures, a lower score indicates better performance or ability. Handicap is a number computed in golf that is an assessment of a golfer's ability. It is calculated as the mean difference between a player's score minus the par score for the course. For example, a player who typically gets a 74 on courses with pars of 72 will have a handicap of 2. Thus, lower handicaps signify better players.

We also obtained three subjective reports on their performance. Participants rated their putting abilities compared to others with their handicap, putting on that day relative to their regular putting abilities, and play on that day relative to their regular playing abilities on a scale from 1 to 7, where a 1 meant that they had their best day and a 7 meant they had their worst day.

Results and Discussion

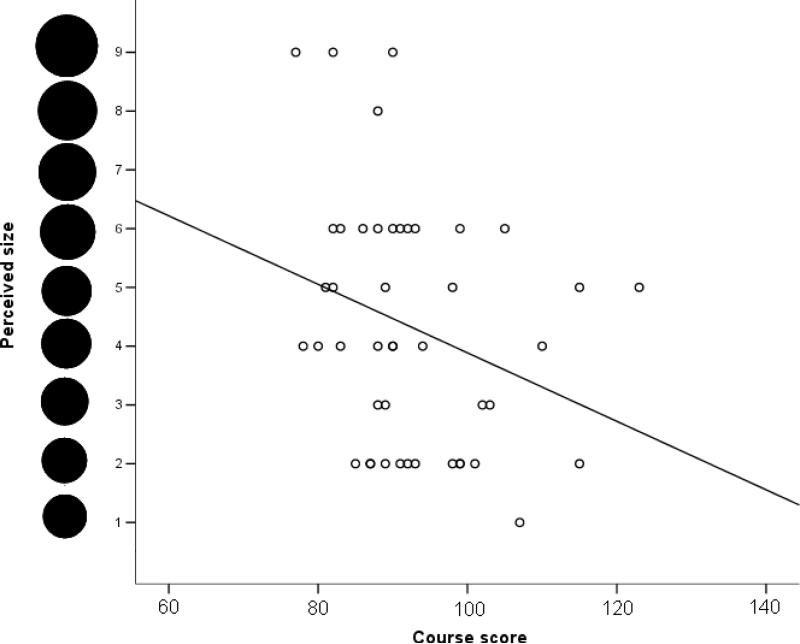

As shown in Figure 1, players who played better, thus having lower scores on the course that day, judged the size of the hole to be bigger than players who played worse, and thus, had higher scores (r = -.30, N = 46, p = .02, one-tail, Spearman rank-order correlation). In contrast, handicap, which is a measure of longer-term playing ability, was not significantly correlated with judged hole size (r = -.19, N = 381, p = .12, one-tail, Spearman rank-order correlation). Recall that a lower handicap signifies a better player. Combined, these results suggest that better players did not see the hole as being bigger, but players that were playing better on that given day did see the hole as bigger.

Figure 1.

Apparent size of a golf hole as a function of score on the course that day. Each circle represents 1 or more participants’ data. The circles on the y-axis are drawn to preserve relative size of the stimuli. The solid line is the correlation between course score and the circle selected as best matching the size of the hole.

Furthermore, players who took fewer putts to get the ball in the hole on the 18th green judged it to be bigger than players who took more putts (r = -.26, p = .043, one-tail Spearman rank-order correlation). The correlation between total strokes on the 18th hole and its judged size was not significant (p = .14), implying that this effect was specific to putting performance, for which hole size is relevant. There were no significant correlations with any of our subjective measures of performance (ps > .2), so self-assessed performance did not relate to apparent hole size, whereas actual performance did.

Our results expand on earlier research with softball players where we showed that batters who were hitting better on that day recalled the softball to be bigger (Witt & Proffitt, 2005). In this experiment, golfers who were playing better judged the size of the hole to be bigger, thus demonstrating another link between perception and performance. While we found a significant correlation between perception of hole size and golf performance on that day (as assessed by course score), we did not find a significant correlation between perception of hole size and how good a player is (as assessed by handicap). This result implies that a highly skilled player such as Tiger Woods does not always see the hole as bigger just because he is a terrific player, but rather, any person can see the hole as being bigger on those days in which he or she is playing well. However, a non-significant correlation is difficult to interpret, and perhaps a significant correlation would have been found with more participants or a wider range of handicaps. In our experiment, handicap ranged from 7 to 36 (range = 29) whereas course score ranged from 77 to 123 (range = 46). Since we only measured day-of performance in the softball study as well (Witt & Proffitt, 2005), the current study raises an interesting question: what aspects of performance and performance capacity relate to perception? Future research should include a longitudinal study to see if perceived size changes for a player of a given handicap as performance levels rise and fall.

We also found that apparent hole size was correlated with putting performance on the last hole but not with overall performance on the last hole suggesting that these effects are specific to the relevant task. Finally, apparent size is not related to subjective measures of performance. Players who think they are playing better do not necessarily recall the hole as appearing bigger.

Study 2

As with the softball study (Witt & Proffitt, 2005), we cannot be sure whether performance influenced perceived hole size or remembered hole size. The next two studies addressed this question. In Study 2, we sought to replicate the effect of performance on remembered hole size in a laboratory context. Study 3 was similar in design to Study 2 except that apparent size judgments were made while the putting hole was in view.

We used a standard practice putting mat, which was placed in the laboratory. Putting performance was manipulated by having some participants putt from very close to the hole while others putted from farther away. We tested if participants in the Easy (close) condition judged the hole to be bigger than participants in the Hard (far) condition.

Method

Participants

Forty (15 male, 25 female) University of Virginia students, ranging in age from 18 to 34, participated in this experiment for either a snack or to fulfil a research requirement for course credit. All participants indicated that they would play golf right-handed and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. All gave informed consent.

Stimuli and Materials

By their choice, participants used one of two right-handed golf putters. One was .93 m long and the other was .89 m long. They putted on an indoor, practice putting mat that was 2.15 m long and .34 m wide. The mat sloped upwards at a 10° angle .42 m before the hole. The hole was 9.52 cm in diameter. Estimated hole size was collected in Microsoft Paint using a standard computer mouse and keyboard.

Procedure

Participants were assigned to either the Easy or the Hard condition in alternating order. For the Hard condition, participants stood 2.15 m away from the front of the putting hole, and for the Easy condition, participants stood .4 m away from the hole. Participants were instructed that after some practice putting, they would have to putt the ball 10 times. We asked participants to predict how many of their 10 putts they thought they would make. We then told the participants that if they could make the number of putts that they predicted, they would receive a reward of their choice of candy, soda, chips, or Gatorade. They were then given 2 minutes alone to practice putting before attempting their 10 putts. After practicing, the experimenter instructed the participant to take 10 putts. Upon completion of their putts, all participants were given their choice of snacks, regardless of whether they made their predicted number of putts.

Participants were then directed into another room to perform a visual matching task. They were instructed to sit in front of a Dell laptop, which already had the drawing program, Microsoft Paint, opened. MS Paint is a simple drawing program that consists of a sketching area and several types of drawing tools such as a paintbrush or shape tools. The sketching area was always blank to start. Participants used the ellipse tool by holding down the shift key and dragging the mouse in order to draw a filled-in black circle. They were instructed to draw the circle to match the physical size of the actual size of the putting hole. If they were unsatisfied with their drawing, they were allowed and encouraged to redraw until they were satisfied that the circle drawn on the screen matched the size of the hole.

Results and Discussion

Not surprisingly, participants in the Easy condition (M = 60.0%, SE = 5.13%) predicted making more putts than the Hard condition (M = 38.3%, SE = 3.44%), t(38) = 3.52, p < 0.01 (one-tailed), d = .55. Also, a higher percentage of putts were made in the Easy condition (M = 73.5%, SE = 4.06%) compared with the Hard condition (M = 24.5%, SE = 4.38%), t(38) = 8.206, p < 0.01 (one-tailed), d = 1.30.

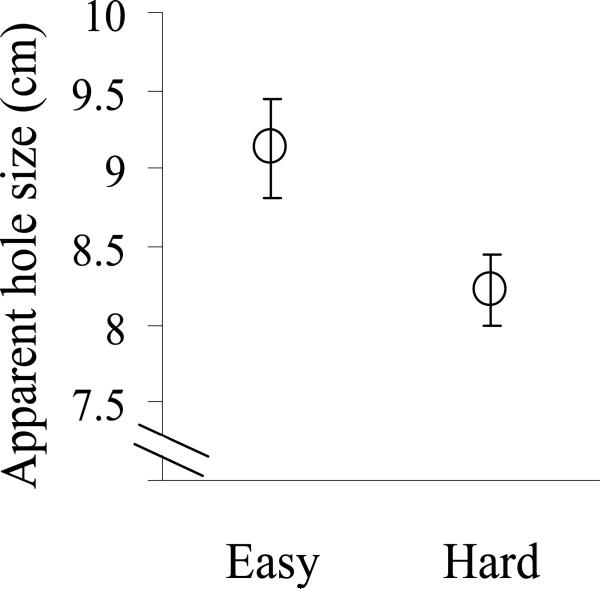

More interestingly, participants in the Easy condition drew the circle bigger than participants in the Hard condition (see Figure 2), t(38) = 1.69, p = 0.05 (one-tailed), d = 0.27. This result suggests that participants in the Easy condition perceived the hole to be bigger than participants in the Hard condition, so they drew larger circles as matching the size of the hole. Since putting is more difficult from a farther distance and performance was markedly worse in the Hard condition relative to the Easy condition, these findings suggest that putting performance influences apparent hole size.

Figure 2.

Apparent size of the golf hole in the putting mat by condition in Study 2 as measured by drawing circles in Microsoft Paint. Actual size of the hole was 9.52 cm in diameter. Participants did not have vision of the hole when making their estimates. Error bars represent one standard error of the mean.

However, there are two concerns with this experiment. First, participants had different views of the hole while putting. Participants in the Easy condition were closer to the hole, so the hole subtended a larger visual angle and exhibited less projected compression in its aspect ratio. It is possible that these different viewpoints accounted for differences in apparent hole size.

The second concern is that participants did not have vision of the hole when they estimated its size. Thus, the differences in apparent hole size may be due to an effect of performance on memory rather than on perception. This critique applies to Study 1 and to the finding that batting performance influences apparent ball size (Witt & Proffitt, 2005). Thus, in the last experiment, we ran the same procedure as in Study 2 except that participants viewed the hole while making their size judgments.

Study 3

As in Study 2, participants putted from either a near distance or a far distance. However, when these participants made size judgments, they had full vision of the hole. Moreover, all participants judged hole size from the same location, and thus, had the same viewpoint of the hole while making judgments of its size.

Method

Participants

Fifty (21 male, 29 female) University of Virginia students, ranging in age from 17 to 34, participated in this experiment for either a snack or to fulfil a research requirement for course credit. All participants golfed right-handed and had normal or corrected to normal vision. All gave informed consent.

Stimuli and Material

The same golf putters and putting matt was used as in Study 2. Estimated hole size was collected in Microsoft Paint using a standard computer mouse and keyboard.

Procedure

Participant completed the same procedure as completed in Study 2 except participants drew the size of the putting hole while the looking at it. After participants finished putting, they were instructed to sit in front of a Dell desktop computer, which was situated beside the golf mat, approximately 1 m to the right of the putting hole. Participants were instructed to use the ellipse tool in Microsoft Paint to draw a circle that was the same physical size as the actual size of the putting hole. Participants were allowed to look back and forth between their drawing and the hole as much as they liked, and they were allowed and encouraged to redraw the circle until they were satisfied that the circle on the screen matched the size of the hole.

Results and Discussion

As in Study 2, participants predicted making more putts in the Easy condition (M = 60.00%, SE = 3.92%) than the Hard condition (M = 36.80%, SE = 3.25%), t(48) = 4.56, p < 0.01 (one-tailed), d = .65. A higher percentage of putts were made in the Easy condition (M = 68.8%, SE = 4.45%) compared to the Hard condition (M = 28.00%, SE = 3.32%), t(48) = 7.36, p < 0.01 (one-tailed), d = 1.04.

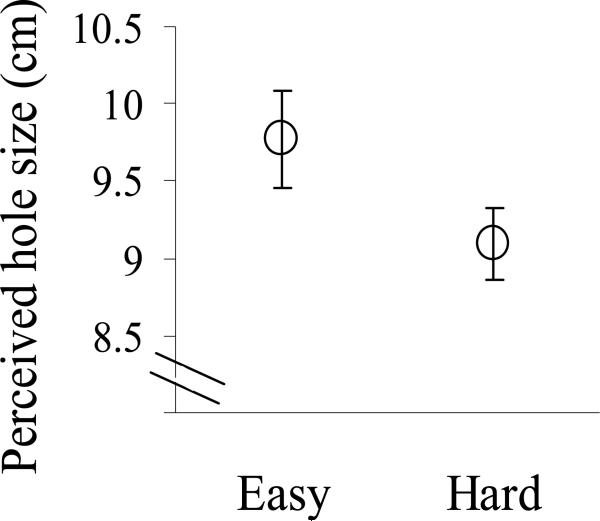

As predicted, participants in the Easy condition drew the circle bigger than the participants in the hard condition, t(48) = 1.73, p = 0.05 (one-tailed), d = 0.24 (see Figure 3). Even when participants had full vision of the hole, they perceived its size differently. Thus, putting performance influences perceived hole size and not just remembered hole size.

Figure 3.

Perceived size of the golf hole in the putting mat by condition in Study 3 as measured by drawing circles in Microsoft Paint. Actual size of the hole was 9.52 cm in diameter. Participants had vision of the hole when making their estimates. Error bars represent one standard error of the mean.

Participants in the two groups viewed the hole from different distances while putting. However, both groups viewed the hole from the same distance when making their judgments. Thus, we think it is unlikely that viewing distance alone can account for our results. Furthermore, an effect solely due to viewing condition would likely produce results contrary to the findings of Study 1 since better golfers can typically make putts from farther away.

General Discussion

In three experiments, we demonstrated that golfers perceive the size of the hole relative to their golfing performance. In the first experiment, we solicited golfers after they played a full round of golf and asked them to judge the size of the golf hole. We found that judged hole size was negatively correlated with the players’ performance that day. Players who played better judged the hole to be bigger. This finding is consistent with our early finding that softball players who are batting better judge the ball as being bigger (Witt & Proffitt, 2005).

However, while course score correlated with apparent hole size, handicap did not. Thus, perception may not be a function of how good a player is but rather how good that player is playing at that specific moment. Our sample of golfers was somewhat limited to relatively unskilled golfers, so we are not sure if this statement would generalize over a wider range of abilities that include very skilled or professional golfers. In Experiment 1, the mean handicap was 18.2, and in Studies 2 and 3, only 38% of all subjects had experience with golf. It would be interesting to see how golfer's perception of the hole changes from day to day and whether the variation in perception differs across levels of expertise.

Apparent cup size correlated with putting performance on the last hole but not with overall performance on the last hole suggesting that these effects are specific to the relevant task. Based on data from the last hole, the apparent size of the hole is only influenced by performance on tasks that directly involve the hole. In this case, the only relevant task involving the hole's size was putting, not driving or hitting. Except for those seemingly miraculous shots in which the ball happens to go into the cup from outside of the putting green, hole size becomes relevant only when putting. Consequently, performance on strokes other than putting ought not to contribute to the apparent size of the golf cup.

Finally, in these studies, apparent size was not related to subjective measures of performance. Players who thought they were playing better did not necessarily report the hole as appearing bigger. Only actual performance affected the recalled size of the golf cup. As a result, the apparent size of the cup may be independent of several traits of the player including perhaps their confidence, optimism, or general attitude towards themselves. Since these traits can affect performance (Stone, Lynch, Sjomeling, & Darley, 1999), one might think they would have also affected perception. However, more detailed experiments would be needed before making any definite claims about the relationship between attitude and perception.

In the last two experiments, university students putted golf balls on a turf putting mat from a location close to the hole or one that was far from it. Then they judged the size of the hole either from memory (Study 2) or while still viewing the hole (Study 3). In both experiments, participants who putted from the closer location drew the matching circle to be bigger than participants who putted from the far location. The results of Study 3 demonstrate that people's putting performance can affect their perception of the hole's size, as opposed to just inducing a memory bias.

Although these results suggest that a relationship exists between performance and perception, the causal direction of this finding is unclear. For example, do golfers putt better, and therefore, see the hole as bigger, or do they see the hole as bigger, and therefore, putt better? The current experiments do not speak to this question; however, we speculate that the relationship is reciprocal such that perception and performance likely influence each other.

Our findings are consistent with other research showing effects of action potential on perception. Targets that are placed just beyond arm's reach look closer when a perceiver intends to reach with a tool than when the perceiver intends to reach without the tool (Witt, Proffitt, & Epstein, 2005). Hills look steeper (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999) and distances look farther (Proffitt, Stefanucci, Banton, & Epstein, 2003) when the perceiver wears a heavy backpack, and thus, would have to exert more energy to walk. Similarly, targets look farther away when people have to throw a heavy ball compared with a light ball to them (Witt, Proffitt, & Epstein, 2004). In all of these experiments, the optical information was held constant, yet perception varied depending on the perceiver's ability to perform the intended action.

In summary, our results demonstrate that people's perceptions of target size are scaled by their current abilities to act effectively on the target. In turn, golfers who are playing better see the hole as bigger relative to golfers who are not playing as well.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIH RO1MH075781-01A2 grant to Dennis Proffitt . The authors wish to thank Ray Ryan and the Providence Golf Club for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Eight participants did not have or did not report their handicap.

References

- Bhalla M, Proffitt DR. Visual-Motor recalibration in geographical slant perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1999;25:1076–1096. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.25.4.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR, Stefanucci J, Banton T, Epstein W. The role of effort in distance perception. Psychological Science. 2003;14:106–112. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J, Lynch CI, Sjomeling M, Darley JM. Stereotype threat effects on black and white athletic performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1213–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Wesp R, Cichello P, Gracia EB, Davis K. Observing and engaging in purposeful actions with objects influences estimates of their size. Perception & Psychophysics. 2004;66:1261–1267. doi: 10.3758/bf03194996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Proffitt DR. See the ball, hit the ball: Apparent ball size is correlated with batting average. Psychological Science. 2005;16:937–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Proffitt DR, Epstein W. Perceiving distance: A role of effort and intent. Perception. 2004;33:577–590. doi: 10.1068/p5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Proffitt DR, Epstein W. Tool use affects perceived distance but only when you intend to use it. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2005;31:880–888. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.31.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]