Abstract

Alcohol consumption and its attendant problems are prevalent among adolescents and young adult college students. Harm reduction has been found efficacious with heavy drinking adolescents and college students. These harm reduction approaches do not demand abstinence and are designed to meet the individual where he or she is in the change process. The authors present a case illustration of a harm reduction intervention, the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS), with a heavy-drinking female college student experiencing significant problems as a result of her drinking. BASICS is conducted in a motivational interviewing style and includes cognitive-behavioral skills training and personalized feedback.

Keywords: harm reduction, alcohol, adolescents, college students, motivational interviewing

Alcohol consumption is a risky behavior prevalent among adolescents and young adult college students. The majority of teenagers and college students consume alcohol at least occasionally; the prevalence of heavy drinking occasions (defined as consumption of five or more drinks in a row at least once in a 2-week period) is estimated at 10% for 8th graders and monotonically increases to 41% for college students (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2009). Heavy drinking can result in a multitude of negative consequences ranging from disruptions in schoolwork, relationship problems, legal troubles, physical injuries, sexual assaults, and death (Perkins, 2002).

As such, numerous prevention and intervention approaches have been implemented with young people to curb heavy drinking and reduce its consequences. Although the majority of college campuses and high schools have alcohol policies and programs, they vary in content and may not be empirically supported. Information and education-only approaches, which often emphasize abstinence, are typically ineffective with young people (DeJong, Larimer, Wood, & Hartman, 2009; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2002), Thus, it is important for clinical practitioners and school personnel to be familiar with the programs achieving documented success.

Harm Reduction

Multiple scholarly reviews have demonstrated the efficacy of harm reduction with adolescents and college students (e.g., Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Larimer & Cronce, 2007; White, 2006). Harm reduction strategies meet students where they are in the change process and do not require abstinence or utilize scare-tactics that focus on the most severe (versus most likely) negative consequences (Marlatt, 1998; Neighbors, Larimer, Lostutter, & Woods, 2006). Harm reduction approaches can reach young people who may not perceive much harm in their current level of drinking. For example, some students may view the traditional negative effects of alcohol (e.g., impulsive sexual behavior, missing classes) as neutral or positive. In addition, young people may view drinking as normative and may experiment with alcohol to gain acceptance from peers. Using harm reduction strategies that focus on an individual’s personal experiences with alcohol (both negative and positive) serves to lessen resistance and increase openness to considering change. For young drinkers, any movement toward reduced drinking and consequences may be viewed as a success.

The most successful alcohol interventions with young adults utilize both psychoeducation and personalized feedback in the context of motivational interviewing (MI)—a nonjudgmental and nonconfrontational therapeutic approach designed to build intrinsic motivation to change problematic behavior (Arkowitz & Westra, 2009; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MI has long been associated with a transtheoretical model that posits individuals cycle through stages of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance) when modifying behavior (Prochaska & DiClemente, 2005). Although individuals in the action stage typically benefit most from cognitive-behavioral techniques, individuals in the precontemplation stage (not considering change) or contemplation stage (beginning to think about change) tend to benefit most from strategies that enhance awareness, build motivation, and move them into preparation. Most young people who drink heavily can be categorized as precontemplative or contemplative, and harm reduction strategies based in MI appear to be most effective when working with this population.

Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students

The Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) is one of the most successful empirically supported prevention and intervention programs for college students and adolescents (Baer, Kivlahan, Blume, McKnight, & Marlatt, 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998). BASICS comprises a two-session intervention (50-minute assessment session followed by a 50-minute feedback session) that combines MI strategies, cognitive-behavioral skills training, and personalized feedback. Several adaptations of BASICS have utilized paper- or Web-based assessment rather than an in-person assessment interview (see Larimer & Cronce, 2007).

Components of the BASICS assessment session are, generally, as follows: (a) building rapport; (b) assessment of typical and peak drinking occasions, perceived normative drinking behavior of other students on campus, alcohol dependence symptoms, reasons for using alcohol, expectancies regarding alcohol’s effects, protective strategies used before or during drinking, and family history; and (c) reviewing the United States’ definition of a standard drink (i.e., a drink containing 0.6 ounces of pure [100% by volume or 200 proof] alcohol). Students are provided with monitoring cards and asked to document their drinking behavior between sessions (1 to 2 weeks). A personalized feedback report is generated following the assessment session.

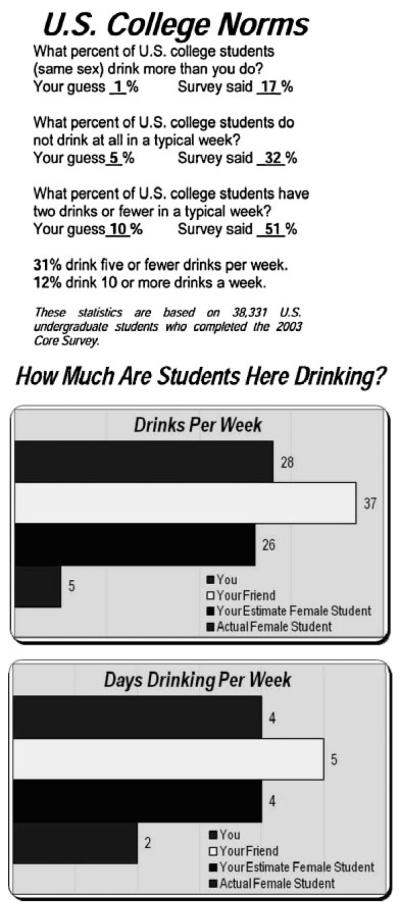

The BASICS feedback session, conducted in MI style, includes both presentation of selected alcohol information and review of the personalized feedback report. The alcohol information discussed typically includes alcohol metabolism and the factors associated with rates of absorption and elimination (e.g., stomach content, body weight, sex differences), personal risk based on family history and other substance dependence issues, factors affecting tolerance, and negative consequences pertinent to the individual’s experience (e.g., academic or relationship problems, sleep disturbances, hangovers). Students are provided with personalized blood alcohol level (BAL) cards detailing their estimated level of intoxication based on the number of drinks consumed per hour spent drinking. Personalized feedback regarding social norms for drinking allows students to see the discrepancies between how they think other students on campus drink and how students on campus actually drink (see Figs. 1 and 2). In nearly all occasions, heavy-drinking students overestimate the drinking behavior of their peers at both distal (e.g., typical student at the university) and proximal levels (e.g., typical fraternity member). Providing students with accurate normative data to correct these misperceptions is an essential component of BASICS, and this type of social-norms approach has been effective in stand-alone in-person, group, mailed, and computer-based interventions (Larimer & Cronce, 2007; Walters & Neighbors, 2005). BASICS facilitators also discuss students’ specific reasons for drinking, including their expectations regarding alcohol’s effects and provide information regarding alcohol expectancy challenge research (i.e., “placebo” studies where expectancy effects such as increased sociability emerge when individuals believe they are consuming alcohol in bar-like settings).

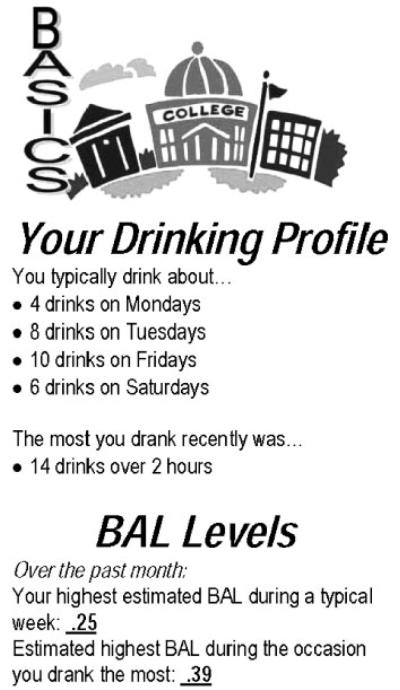

Figure 1.

Example of drinking feedback.

Figure 2.

Example of normative feedback.

BASICS and related approaches implemented in the context of brief motivational enhancement sessions have been effective in preventing heavy drinking and in intervening with established drinkers in both voluntary and mandated young adult populations (see Carey et al., 2007; Larimer & Cronce, 2007), and they have been shown to reduce both heavy alcohol use and related harmful consequences of drinking (Baer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998). BASICS has been designated as a Tier I intervention for college student drinking prevention/intervention by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Task Force (NIAAA, 2002) and as a model program by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA, 2008). The following case illustration demonstrates the use of BASICS to reduce harm associated with heavy drinking in a university student participating voluntarily in a randomized clinical trial.

Case Illustration

Client Description

Tiffany, an 18-year-old single Caucasian, had recently begun spring quarter of her college freshman year. Several weeks into the quarter she was recruited for a study involving brief alcohol interventions for college students and randomized to receive a single-session BASICS intervention. Tiffany completed a screening survey in which she reported 15 episodes of heavy episodic drinking (i.e., for females, consuming four or more drinks over the course of 2 hours) in the past month. One week later, she completed a web-based baseline survey regarding her drinking behavior and related constructs. At baseline, she endorsed experiencing nine types of alcohol-related consequences in the past 3 months: not being able to do her homework or study for a test; getting into fights, acting bad, or doing mean things; going to school drunk (i.e., still being drunk from the night before); neglecting her responsibilities; having a fight with a friend; having a bad time; missing school; continuing to drink when she had promised herself she would not; and feeling that she had a problem with alcohol. These problems were precipitated by episodes of heavy drinking. Tiffany estimated that she consumed 28 drinks per week, typically consuming 4 drinks on Mondays, 8 drinks on Tuesdays, 10 drinks on Fridays, and 6 drinks on Saturdays. The most Tiffany had consumed on a single occasion in the month prior to her BASICS intervention was 14 drinks in 2 hours, reaching an estimated peak BAL of .39.

Tiffany reported that neither of her parents were problem drinkers (her father was a nondrinker and her mother was an occasional drinker), but she reported that one or more of her parents’ siblings had an alcohol problem. Tiffany tried alcohol and became intoxicated for the first time at age 15. She indicated that she had not received any previous treatment for drinking. Tiffany endorsed some symptoms of anxiety but no other current psychiatric symptoms. Tiffany and Tiffany’s family psychiatric history, including psychotherapy or psychotropic medication treatment, were not assessed.

When Tiffany was surveyed regarding recent significant life events that might impact her functioning, she reported a major (unspecified) disappointment in school, an increase in arguments with her close friends, her close friends moving away, and her own move into the campus residence halls as stressors. She reported doing well in school, indicating that her most recent GPA was between 3.0–3.5 on a 4.0 scale (a B average). Tiffany did not practice a formal religion, was not romantically involved at the time of the assessment, and reported never having a romantic relationship for longer than 3 months.

Case Formulation

In conceptualizing this case, we considered Tiffany’s primary motives for drinking, how she thought about her drinking in comparison to her peers, and her current readiness to change her drinking behavior.

Socially motivated to drink

Tiffany’s self-reported motives for alcohol consumption were primarily social in nature. Tiffany noted that she used alcohol as a social lubricant and because it made her feel less self-conscious by shifting the focus of her attention to external factors. She discussed having had a large group of friends in high school and that she had found the process of making new friends as a freshman at the university difficult. Tiffany identified alcohol as a primary ingredient in the development of these new friendships. She reported drinking less during her first quarter of college, but noted recently becoming closer with a group of women who drank heavily. Tiffany said that she was not particularly fond of drinking and disliked the taste of most alcohol, but indicated that her friends frequently drank and that she did not like to be around her friends when they were drinking and she was not.

Perceives own drinking as typical

Tiffany estimated that the average female student drinks about 26 drinks per week, usually over the course of four drinking days. As is often the case, her estimation far exceeded the actual average for females from the same university: five drinks per week over the course of two drinking days. Tiffany’s biased perception of a typical female student was likely influenced by the pattern of heavy drinking evidenced by her immediate peer group. At baseline, Tiffany reported that her closest female friend drank a total of 37 drinks across five drinking days in a typical week. Tiffany agreed that she used her friends as a gauge for her own drinking. In the context of these relationships, she experienced her level of drinking as normal—not something she had thought, nor needed to think, a lot about.

Ambivalent about change

At baseline, Tiffany indicated that she felt she was not drinking too much and there was no need to change her drinking. At the same time, she also agreed with statements suggesting she should consider drinking less alcohol and that she might have a problem with alcohol. When a student is ambivalent about changing her drinking, practitioners are advised to remain focused on the fact that the student did not come to the session asking for help in changing her behavior. Rather, the goal of the session is to assist the student to think more deeply about her drinking habits and foster motivation for changing her habits.

Course of Treatment

After completing the baseline assessment, Tiffany met with a therapist to discuss personalized feedback regarding her survey responses. We have broken the intervention session into primary components: opening and closing the session, discussing motivations and social perceptions of drinking, identifying and working with ambivalence and change talk, and introducing ways to utilize harm reduction strategies. Consistent with an MI style, therapists are taught to listen actively to what the student is saying without jumping to conclusions or making assumptions about the student’s lifestyle. Reflective statements are used to demonstrate and confirm understanding of the student’s perspective, thus building rapport and highlighting ambivalence or conflicting information. Excerpts from the session are provided to illustrate specific elements of the case and BASICS.

Personalized feedback report

A personalized feedback report is prepared for the student prior to the feedback session. This multicolor report is generally one to two pages in with text and graphics presented in an engaging and easily readable manner. Figures 1 and 2 present portions of Tiffany’s feedback report.

A portion of the feedback is usually devoted to motivations for and beliefs about drinking, and another portion is designated for negative consequences resulting from drinking. These portions commonly follow one another and are introduced by the therapist as “Tell me a little bit about what you like about drinking?” “What motivates you to drink?” and correspondingly “What do you like less about drinking?” and “We’ve talked about the things that motivate you to drink—are there things that motivate you to not drink?” This balanced approach allows for a richer examination of drinking and reduces the likelihood that the student will experience the alcohol intervention as inappropriate for her circumstances, or feel like she is being lectured. It is also typical for the feedback report to include a section on risks, providing information about what puts one at increased risk for long-term alcohol problems such as drinking and driving, increased tolerance, and familial risk.

Opening the session

Tiffany’s BASICS intervention was provided by a peer facilitator, a college senior who had received extensive training and supervision in conducting these interventions. The facilitator was trained to interact with students in a warm and genuine style, while also refraining from reinforcing less effective behaviors (e.g., not laughing when the student made jokes about the impact of alcohol on her life). The facilitator began the session by engaging in nonspecific rapport building (e.g., “How is your quarter going so far?” “How was the survey?”). Then she provided an overview of what the student could expect (e.g., “We’ll be working together for about an hour,” “This is sort of like a check-up,” “I’m not here to tell you what you should or shouldn’t do.”).

Typical drinking context and motivations for and beliefs about drinking

The facilitator asked the student to describe a typical drinking occasion, including the setting (e.g., place/event, people present), alcohol consumption (i.e., how many drinks over what period of time, what type of drinks), and any concomitant activities (e.g., playing drinking games, talking with friends).

Facilitator: So, first off, can you just give me an idea about how alcohol fits into your life?

Student: It’s mostly a partying thing. When I go out partying, that’s when I drink.

Facilitator: So, it’s a social thing…

Student: Yeah, social. Yeah. Sure.

Facilitator: So, if I was a fly on the wall somewhere in a place where you were partying or drinking, what would I see?

Student: Like going out? Usually, I don’t know. It’s with my… a lot of my friends, my girlfriends, we go out, and just have a good time. We like to dance and just drink. I don’t know … (laughs). I don’t know exactly what we do all the time … it changes.

Facilitator: How much do you usually drink on a typical occasion?

Student: Um, probably 6, maybe 7.

Facilitator: Okay. Over how long?

Student: Like, 2 to 3 hours.

Facilitator: Two to 3 hours. Okay. What do you usually experience when drinking?

Student: Experience? What do you mean experience? (laughs)

Facilitator: What is it about drinking that you like?

Student: I don’t know. I feel like it makes me more social, even though I’m really social anyways … but, it just makes … I don’t know. Cause when everyone else is doing it, you know, you don’t have as much fun if you’re sober with everybody else … when they’re all drunk. Drunk and annoying… (laughs). But, I don’t know. It just makes me more open I guess.

As the facilitator continued to probe for information about Tiffany’s motivations and expectations for drinking, Tiffany indicated that she and her friends typically drank at events hosted by fraternity houses, during which she was provided alcohol at no cost. Tiffany repeatedly stated that her friends usually consumed alcohol at these events and she felt uncomfortable abstaining from drinking when her friends drank.

In this next excerpt, the facilitator attempts to explore Tiffany’s experience on occasions when she did not drink.

Facilitator: Can you think of a specific time [when your friends were drinking] … that you felt you wish you had been drinking?

Student: I don’t ever really. If I don’t drink, it’s for a certain reason. So, I don’t really wish that I had been drinking.

Facilitator: Okay. What are usually the reasons you don’t drink?

Student: If I have an early class, or a test, or if I’m doing something really important the next day, I don’t want to be high the next day.

Facilitator: So, sometimes you have other priorities.

Student: Yeah… drinking’s not a number one priority for me.

Exploring perceptions of typical drinking

Tiffany was 5′8″ and weighed 150 pounds at baseline. Based on her sex and weight, it takes about 2 hours for one standard drink to clear her system. In this next interview excerpt, the facilitator reviews a portion of the feedback that compares Tiffany’s estimate of how much other students drink in comparison to her. Tiffany estimated that 30% of college students drank more than she did. Based on the rates reported by 33,000 college students, only 1% of college students drink more than she does. This information is provided in a factual, nonjudgmental fashion, and the facilitator allows the student to sit with and reflect on this information.

Facilitator: So, what are you thinking when you look at that?

Student: That’s kinda … uh … I don’t know. Does that take into account people that don’t live on campus?

Facilitator describes how normative data was obtained.

Student: Yeah. So that’s … I feel (nervous laugh) … bad (more nervous laughter).

Facilitator: Doesn’t really fit in with what you thought.

Student: No … (nervous laugh). Not at all.

Facilitator: Yeah, because you thought it was more like 30%.

Student: Yeah.

At this point, a facilitator might ask the student to reflect further on why she thinks her estimates were inaccurate. This will often lead to a discussion of what is considered normal drinking in the student’s specific peer group. Facilitators might present a double-sided reflection, “On one hand you’ve got this group of friends with whom you are drinking about the same as or more than you, and on the other hand, I’m presenting this evidence that the rates at which you are drinking are above the average student. How do you reconcile these two things?” The development of discrepancy builds her motivation to reduce her drinking.

Addressing ambivalence

BASICS interventions are designed to meet students where they are in terms of readiness to change and to work with and resolve their ambivalence. This contemplative process is often initiated as students recount their behaviors during baseline assessment and can be bolstered during the session as demonstrated in this excerpt.

Facilitator: You mentioned that you felt you had a problem with alcohol.

Student: Mostly, when I was taking this survey, ‘cause I didn’t realize how much I drank until I actually thought about it.

The facilitator acknowledges statement without interrupting the student.

Student: I didn’t think I drank that much, and then I started counting it, but it’s been more this quarter. I didn’t drink half as much as this last quarter. Well, I did kind of towards the end of winter quarter, but, it wasn’t … I probably went out once, maybe twice a week, if that.

The facilitator explores what Tiffany feels has changed from last quarter to the current quarter, then returns to discuss how thinking about her recognition that she is drinking more recently has impacted her intended behavior.

Facilitator: So, after you filled out the survey, did you feel like you wanted to drink less, or was it [more] like “I didn’t know I drank that much?”

Student: Uh … I wanted to drink a little less, but it didn’t, like, really affect me that much.

Facilitator: Mm hmm.

Student: Like, cause, I don’t feel I have a problem yet … and I hope it doesn’t get to the point where I do have a problem.

Facilitator: What do you think would be the signs that you were developing a problem? How would you know?

Student: Um … If I wanted to drink in the morning, like, when they asked those questions, I was, “uh-uh.” To open a beer in the morning and drink it, I would throw up.

Facilitator: Yeah.

Student: That’s gross.

Facilitator: That doesn’t sound very good.

Student: Yeah. Or, if, like … I couldn’t say “no” to going out.

The facilitator continues to explore what indicators the student feels would signal a problem with alcohol. Tiffany paraphrased additional DSM-IV symptoms of substance dependence (spending excessive time in alcohol-related activities, failure to fulfill role obligations). The student consistently, yet indirectly, states her perception that the negative consequences are minor, have not had lasting effects, and are not wholly attributable to her alcohol use. This provides an indication of Tiffany’s ambivalence—she does recognize she is drinking more than she thought and that her drinking has increased, but the consequences she has experienced are less severe than those that she would see as an alcohol problem.

In response to this indirect resistance, and given that this exchange occurred early in the session, the facilitator elected to affirm and reflect back on Tiffany’s statement of concern (“I hope it doesn’t get to the point where I do have a problem”) before shifting focus to other feedback.

Facilitator: I know that you mentioned that you don’t really feel like alcohol is not like this big thing in your life.

Student: Yeah … (nervous laugh).

Facilitator: I guess it would just be something to keep an eye on, so you don’t worry about it.

Student: Yeah.

Although this response reduced evident resistance, the facilitator could have alternatively elected to make an amplified reflection of Tiffany’s perception that her drinking did not result in significant negative consequences. For example, the facilitator could have said “So drinking doesn’t get in the way of anything for you.” This overstatement (or amplification) of Tiffany’s perception could have led her to recall and discuss times when drinking did result in unwanted consequences.

Change talk

As is common in BASICS sessions, the facilitator noticed that the student was saying two, almost opposite things during this early part of the session. On the one hand, Tiffany repeatedly reported that alcohol was not causing any serious problems in her life, while on the other hand, she reported concern about her drinking habits. It was the facilitator’s goal to hold both of these perspectives in mind and to reflect this disparity. In this excerpt, Tiffany and the facilitator are reviewing the student’s peak BAL in the past month, an episode where the student drank 14 drinks in 2 hours and had an estimated BAL of .39.

Facilitator: So, what do you make of that?

Student: I don’t know. That’s kind of scary, but I don’t know.

Facilitator: It’s a little bit surprising.

Student: Yeah. I didn’t think it would be that high.

Facilitator: ‘Cause, like you said, you felt like you were safe [even though] you experienced a blackout.

Student: Yeah. I would never drink that much again though.

This last statement is a clear example of what is called change talk in MI. The presence of change talk is associated with reductions in alcohol use and improved outcomes. Tiffany offered several other examples of change talk: “I wanted to drink a little less,” “drinking’s not a number one priority for me,” and “I hope it doesn’t get to the point where I do have a problem.” It is important that facilitators identify and reinforce change talk as it occurs in session. This may be as simple as repeating what the student said in a more definitive tone or may launch the facilitator into an examination of what that change might look like.

In Tiffany’s case, the facilitator followed her change talk by exploring what she wanted to avoid about this experience in the future. The facilitator subsequently provided education on the biphasic effects of alcohol, juxtaposing the myth that continued drinking results in perpetual maintenance of stimulation effects with facts regarding the point of diminishing returns (i.e., when continued drinking results in more negative/undesired effects than positive/desired effects). This level of drinking, typically corresponding to a BAL of .05–.06%, becomes a focus of subsequent discussion regarding risk reduction for Tiffany.

Harm reduction targets

As Tiffany became more aware of the ways in which her drinking was negatively impacting her, the facilitator discussed possible harm reduction strategies. Because Tiffany was not sure she was ready to change her drinking, these strategies were explored in an open fashion as possible strategies. One target could be a reduction in the total number of group drinking occasions per week.

Facilitator: What do you think your friends would say if you said “Let’s not drink tonight?”

Student: They would say “Oh, come on” and they would probably try to get me do it a couple times, but then after I said “No, enough,” they would say, “Okay, whatever, that’s fine.”

Facilitator: So they would be okay with you not drinking. But they would still drink?

Student: Yeah. They would still drink.

Tiffany went on to restate her preference to drink if her friends were drinking. As such, an alternative harm reduction goal could be to support a reduction in the total number of drinks consumed per occasion or the spacing of these drinks over a longer period of time. The facilitator explored with Tiffany the idea of drinking within a zone that would achieve her desired effects while minimizing the likelihood of negative effects associated with higher BALs.

Facilitator: So, 4 drinks in 2 to 3 hours would put you at a .088. So, that’s just past the point of diminishing returns. If you had three drinks in 2 to 3 hours, that would put you at a .058; basically .06. How would you feel about drinking in that zone?

Student: I think I would be a little bit more loose, but I’m not, like, out of it and all.

Facilitator: Mm hmm. You’d kind of feel more relaxed.

Student: Yeah.

Facilitator: Maybe a little buzzed.

Student: Yeah.

Facilitator: But you’re not, like … you’re still completely yourself, and, obviously, not blacking out.

Student: No. Not at all.

Facilitator: That’s kind of like your extreme level [referring to blacking out].

Student: Yeah.

At this point in the session, the facilitator asks the student to imagine the social consequences of not drinking.

Facilitator: Okay. Do you think your friends would be okay with you just having that many drinks [referring to the target of three drinks in 2 hours]?

Student: Oh, yeah. They wouldn’t care.

Facilitator: They wouldn’t care.

Student: Yeah. No, not at all (laughs).

Facilitator: How would it be for you? How would you feel?

Student: I think I’d be okay.

Closing the session

At the end of the BASICS session, the facilitator provides a summary of the session, reviews any plans the client has made to reduce harmful drinking, and often asks the student to engage in forward thinking. Tiffany was asked to predict what her drinking would be like approximately 5 years in the future, to which she responded with significant change talk.

Student: I probably won’t drink very much.

Facilitator: Mm hmm.

Student: Cause, I don’t like the taste of alcohol all that much. Like, I like some drinks.

Facilitator: Mm hmm.

Student: But, I probably will rarely drink.

Facilitator: Yeah.

Student: Just, ‘cause, it’s not that important for me. I think it’s more of a young … it’s the college experience.

The facilitator provided an extended reflection of the change talk Tiffany had provided and affirmed her goal to avoid developing problems with her drinking. The facilitator also affirmed the support Tiffany had from her family, especially her sisters, in avoiding alcohol problems. The facilitator thanked Tiffany for participating in the discussion of her feedback, and provided a packet of resources if Tiffany wanted more information about her drinking. A copy of the personalized feedback was provided for Tiffany to take home. The facilitator also encouraged Tiffany to call if there were any further things she wanted to discuss.

Outcome and Prognosis

Following the session, Tiffany completed a questionnaire about her experience during the session and what impact she expected the session to have on her behavior. Tiffany was positive about the session, indicating that she would recommend the session to a friend and that she found the interviewer highly organized, warm, and competent. She reported the most helpful piece of the session for her was “the statistics that were given. I thought that I was pretty close to being the typical student, but I’m not even close.” She was neutral about whether she was leaving the session with a specific goal in mind for changing her alcohol use. Although Tiffany did not endorse specific plans to change, the goal of the session was achieved—Tiffany evidenced behaviors suggesting that she had begun to contemplate her drinking.

Tiffany’s drinking decreased in the months following the BASICS intervention. Approximately 1 and 3 months following participation in the BASICS intervention, Tiffany completed follow-up questionnaires. Compared to her baseline consumption of 28 drinks per week, 1 month later she was averaging 22 drinks per week, and 3 months after she was averaging 11 drinks per week. Additionally, the frequency of engaging in heavy episodic drinking had reduced from eight times per month at baseline to seven times at 1 month and 3 times per month at 3 months follow-up. Correspondingly, she was drinking less often (4 days a week at baseline and 2 days per week at 3-months follow-up). Although the number of drinks Tiffany reported consuming on her peak occasion was still high, she modified her drinking behavior. She increased the amount of time over which her drinks were consumed, resulting in lower BALs (from .39 to .28 and to .23) and reduced risk for harm. The number and types of problems Tiffany experienced as a result of her alcohol consumption also decreased. She reported 9 different types of problems at baseline and five types of problems 3 months later. She no longer had problems getting into fights, acting bad, doing mean things, not studying or doing homework, missing school, drinking when she had planned not to, or feeling she had a problem with alcohol. Though she had not missed school due to drinking, she did report alcohol had led her to neglect some responsibilities.

Clinical Issues and Summary

The case demonstrates how BASICS can reduce excessive drinking and related harmful consequences in a nontreatment-seeking young adult college student. As demonstrated in the excerpts above, the impact of this session began in the assessment, during which Tiffany became aware that she was drinking more than she realized and that her drinking had recently increased. Probable mechanisms of change included the assessment alone, the feedback about how Tiffany’s drinking compared to the norms for college women, information about her peak BAL and the fact that she had consumed a near-lethal dose of alcohol and the facilitator’s reflective, nonjudgmental stance, and exploration of potential harm-reduction goals and strategies (without pressing Tiffany to accept a particular goal). In combination, these strategies were associated with a substantial reduction in drinking and in alcohol-related harmful consequences for this student.

Although Tiffany’s drinking decreased, at 3-month follow-up Tiffany continued to engage in some heavy-drinking episodes, and her heaviest drinking occasion remained above the norm. At this point, a booster session focusing on consolidation of motivation to change and providing cognitive-behavioral skills training tips to continue the progress may be beneficial. Alternatively, many students continue to reduce their drinking on their own following BASICS; BASICS and related brief interventions have been related to continued declines in drinking for periods of 6–12 months after intervention, and these changes have been shown to maintain for periods up to 4 years (Baer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998). Thus, Tiffany’s progress by the 3-month point may only represent the beginning.

The BASICS intervention has been successfully implemented by peer facilitators as well as psychotherapists of more training. Adherence to motivational interviewing spirit and techniques as well as therapist competence are generally judged to be higher among professional therapists; however, research has shown trained peers produce similar outcomes. In the current case, an experienced therapist may have focused more on increasing Tiffany’s commitment to change through exploring her change talk and resolving barriers to using harm reduction strategies. However, such attempts may also have created resistance or resulted in lowered autonomy on Tiffany’s part. The peer facilitator established a strong rapport with Tiffany, likely increasing the effectiveness of the feedback. Psychotherapists at all levels of training can strive for a blend of relational presence and technical strategy, with the goal of clients exploring the impact of their behavior from their unique perspective as a necessary step toward change.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was partially supported by a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant (F31 AA016038-01A2) awarded to Ursula Whiteside.

Selected References and Recommended Readings

- Arkowitz H, Westra H, editors. Motivational interviewing in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session. 2009;65(11) doi: 10.1002/jclp.20640. entire issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Blume AW, McKnight P, Marlatt GA. Brief intervention for heavy drinking college students: 4-year follow-up and natural history. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1310–1316. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Larimer ME, Wood MD, Hartman R. NIAAA’s rapid response to college drinking problems initiative: Reinforcing the use of evidence-based approaches in college alcohol prevention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;16(Suppl):5–11. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2009. p. 73pp. (NIH Publication No. 09-7401) [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies: 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, editor. Harm reduction: Pragmatic strategies for managing high-risk behaviors. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a two-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Kilmer JR, Kim EL, Weingardt KR, Marlatt GA. Alcohol skills training for college students. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, alcohol and substance abuse: Reaching teens through brief intervention. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. pp. 183–215. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64:527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Task Force of the National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2002. A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U.S. colleges. Available at: http://www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/Reports/TaskForce/TaskForce_TOC.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lostutter TW, Woods BA. Harm reduction and individually focused prevention. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The transtheoretical approach. In: Norcross JC, Goldfried MR, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy integration. 2nd ed Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Practices and Programs: Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS) 2008 Retrieved from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/programfulldetails.asp?PROGRAM_ID5156.

- Walters ST, Baer JS. Talking with college students about alcohol: Motivational strategies for reducing abuse. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR. Reduction of alcohol-related harm on United States college campuses: The use of personal normative feedback interventions. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:310–319. [Google Scholar]