Abstract

Experimental Cryptococcus neoformans infection in rats has been shown to have similarities with human cryptococcosis, because as in healthy humans, rats can effectively contain cryptococcal infection. Moreover, it has been shown that eosinophils are components of the immune response to C. neoformans infections. In a previous in vitro study, we demonstrated that rat peritoneal eosinophils phagocytose opsonized live yeasts of C. neoformans, thereby triggering their activation, as indicated by the up-regulation of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules and the increase in interleukin-12, tumour necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ production. Furthermore, this work demonstrated that C. neoformans-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes cultured with these activated C. neoformans-pulsed eosinophils proliferated, and produced important amounts of T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokines in the absence of Th2 cytokine synthesis. In the present in vivo study, we have shown that C. neoformans-pulsed eosinophils are also able to migrate into lymphoid organs to present C. neoformans antigens, thereby priming naive and re-stimulating infected rats to induce T-cell and B-cell responses against infection with the fungus. Furthermore, the antigen-specific immune response induced by C. neoformans-pulsed eosinophils, which is characterized by the development of a Th1 microenvironment with increased levels of NO synthesis and C. neoformans-specific immunoglobulin production, was demonstrated to be able to protect rats against subsequent infection with fungus. In summary, the present work demonstrates that eosinophils act as antigen-presenting cells for the fungal antigen, hence initiating and modulating a C. neoformans-specific immune response. Finally, we suggest that C. neoformans-loaded eosinophils might participate in the protective immune response against these fungi.

Keywords: antigen presentation, Cryptococcus neoformans, eosinophils, T helper type 1 profile

Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans is a pathogenic yeast considered to be a relatively frequent cause of life-threatening meningoencephalitis or disseminated mycosis, especially in immunocompromised individuals.1,2 As in healthy humans, rats can effectively contain the cryptococcal infection, which can persist for prolonged periods.3 Infection caused by C. neoformans primarily induces a granulomatous reaction in the lung, which is the portal of entry for the fungus.4 T helper type 1 (Th1) cells are known to activate cell-mediated immunity whereas Th2 cells induce humoral immunity. However, in granulomatous inflammation as well as in other forms of inflammation, both type 1 and type 2 cytokine participation is recognized.5–7 It is well known that T-cell-mediated immunity is the critical component of protective immunity against infection with C. neoformans, which is consistent with the suggestion that this organism is a facultative intracellular pathogen.2 Furthermore, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are required for effective immune pulmonary clearance and the prevention of extrapulmonary dissemination.8

The cells recruited during the inflammatory response to C. neoformans include neutrophils, eosinophils (Eo), monocyte/macrophages, dendritic cells and lymphocytes (CD4+ T, CD8+ T cells, B cells and natural killer cells). Of these cells, activated macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes are all capable of in vitro killing or growth inhibition of C. neoformans.9

In animal models, C. neoformans is remarkable for its ability to evoke Th2-type polarized immune responses. Moreover, the enhanced virulence among C. neoformans strains is associated with this capacity of being able to elicit a Th2 immune response.10 In addition, susceptibility to experimental cryptococcal infection in certain mouse strains (i.e. BALB/c and C57BL/6) has been linked to increased Th2 and decreased Th1 cytokine production.11,12 It is only generally accepted that Th1 responses afford protection against C. neoformans;13 with the role of Th2 cells in immunity against the organism still not being fully understood.

Eosinophils, on the other hand, are multifunctional leucocytes that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous inflammatory processes, including helminth infections and allergic diseases.14 Although Eo are considered to be terminally differentiated cells that mainly act as the first-line defence against parasites in the tissues in which they reside,15 it has been suggested that these cells are recruited to inflammatory foci, where they can then modulate immune responses to diverse stimuli.16 In addition, several lines of investigation have indicated that Eo may also exhibit characteristics seen in antigen-presenting cells in certain states.17–22 In this regard, previous studies in our laboratory have shown that opsonized live yeasts of C. neoformans can activate Eo, inducing the expression of MHC I, MHC II and co-stimulatory molecules. These fungally activated Eo were then able to stimulate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to proliferate and produce a C. neoformans-specific Th1 immune response.23

The observation that Eo are capable of stimulating a primary response to C. neoformans in vitro23 suggests that they may function as antigen-presenting cells in the stimulation of immunity in vivo. In this sense, it has been demonstrated that Eo migrate and accumulate in the draining lymph nodes of the lungs after an intranasal antigen challenge in sensitized mice.24 Furthermore, it was also seen that antigen-loaded Eo migrate into the local lymph nodes and localize in the T-cell-rich paracortical zones, where they then stimulate the expansion of CD4+ T cells.19

With regard to Eo chemotaxis, CCL11–CCR3 is the most selective Eo chemoattractant axis identified so far.25,26 The molecular mechanisms underlying the migration of Eo to lymph nodes, however, are not fully understood, and lymphoid chemokines could be the source of trafficking for these cells. Related to this, it was observed that interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-3 (IL-3) and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) stimulated dEoL-1 cells (an Eo cells line) and that peripheral blood Eo were capable of responding to the lymphoid chemokines CCL21 and CCL25, which recruit naive T cells and dendritic cells to the lymph nodes.14

The aim of the present study was to explore in vivo the antigen-presenting ability of the peritoneal Eo both before and during C. neoformans infection in rats. Purified Eo exposed to live yeasts of C. neoformans (CnEo) were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) into naive and C. neoformans-infected rats, and then the lymphoid-organ-specific T-cell and B-cell immune responses against C. neoformans were measured. These experiments demonstrated that Eo migrated to the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) to present fungal antigens. This in turn resulted in an increased lymphoid organ cell proliferation, Th1 cytokine up-regulation, Th2 cytokine down-regulation and stronger antigen-specific antibody response. Finally, this study demonstrated that Eo are capable of inducing a protective immunity against C. neoformans infection.

Materials and methods

Reagents and media

For cell cultures, RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mm glutamine and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO) was used. Mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) anti-rat OX-62, CD11c, MBP, CD3, CD45, CD8a and CD4 were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), with the glucuronoxylomannan-specific mAb 3C2 (mouse IgG1) being a generous gift from Thomas R. Kozel (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA) Recombinant rat GM-CSF was obtained from Biosource (Camarillo, CA), 5-(and -6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) was purchased from Molecular Probes™ (Eugene, OR) and [3H]thymidine was obtained from Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica (CNEA, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Animals

Male Wistar rats (7–8 weeks old), weighing 250 g, were housed and cared for in the animal resource facilities of the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Chemical Sciences, National University of Cordoba, following institutional guidelines. These animal resource facilities are accredited as an entity that follows the international norms of the Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals regulation published by the Canadian Council on Animal Care (assurance number A5802-01). All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee, Faculty of Chemical Sciences, National University of Cordoba (resolution number 1135/09).

Microorganism

Serotype A C. neoformans strain 102/85 (National University of Cordoba stock culture collection) was used. This strain is a clinical isolate with a large capsule typified by PCR multiplex and PCR fingerprinting (Centro de Biotecnologia da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil) as C. neoformans var. grubii, which has been used in previous studies.23,27–31 For the i.p. infection of rats, living yeasts of C. neoformans were expanded in Sabouraud media for 72 hr at 30°. Then, these were washed three times with PBS and resuspended in the same buffer at 107 cells/ml before being inoculated into the rats. To perform the experiments, living yeasts of C. neoformans were expanded in liquid Sabouraud media for 24 hr in a gyratory shaker at 30°. Then, these were washed three times with PBS, resuspended at 107 cells/ml and opsonized with 5 μg/ml of mAb 3C2 for 30 min at 37°. Finally, yeasts were washed with PBS and resuspended in supplemented RPMI-1640 for subsequent cultures with Eo.

Isolation and culture of Eo

Eosinophils were purified from the peritoneal cavity of normal rats by washing the cavity with cold PBS, pH 7·3, 0·1% FBS. Cells were centrifuged at 400 g for 10 min and resuspended in 2 ml HBSS 1×. Then, the cells were separated on a discontinuous Percoll gradient (2 ml of a solution of Percoll with a density of 1·090 g/ml and another 2 ml with a density of 1·080 g/ml, carefully overlaid). Tubes were centrifuged at 400 g for 25 min, and the Eo were collected from the middle interface between the Percoll layers.32 The percentage of Eo was > 90%, as assessed by May–Grünwald–Giemsa staining. This population was further purified by negative selection through incubation with anti-CD11c and anti-OX-62 FITC-labelled antibodies for 30 min (to deplete contaminating dendritic cells and macrophages), and then for a further 15 min with anti-FITC MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The resulting Eo population contained < 1% of OX-62 positive cells and < 2% of CD11c-positive cells,23 and the percentage of Eo viability was > 95% as determined by Trypan blue exclusion.

Purified Eo were incubated in supplemented RPMI-1640, with or without opsonized live yeasts of C. neoformans, at 37° in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and in the presence of GM-CSF (5 ng/ml). Twenty-four hours after this culture, Eo were removed from the plates, washed twice with RPMI-1640 and twice with PBS to remove free yeasts, and finally resuspended in PBS before being inoculated.

Migration of CFSE-labelled Eo to lymphoid organs

The CnEo were labelled with CFSE, as described elsewhere33 with minor modifications. Eosinophils were incubated with CFSE at a final concentration of 2·5 μm. Then, labelling was terminated by adding PBS supplemented with 5% FBS, and after three washes a total of 5 × 106 labelled cells resuspended in PBS were inoculated i.p. into naive rats. Spleens and MLN were recovered 24–96 hr later and evaluated for the presence of CFSE-labelled Eo using a FACS Canto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San José, CA). The presence of CFSE-labelled cells was determined using logarithmic-scale histograms and autofluorescence was assessed using spleen and MLN from rats inoculated with unlabelled Eo.

To assess if the CFSE-labelled cells found in the lymphoid organs were definitely Eo, 5 × 105 spleen and MLN cells were plated on a 96-well U-shaped plate. The cells were then blocked with anti-rat FcγRII (CD32) for 15 min at room temperature and stained with phycoerythrin-labelled anti-rat CD3, CD45, CD11c, OX-62 and MBP (intracellular stain for Eo granules) for 30 min under the same conditions. After incubation, the cells were collected by centrifugation, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, washed three times with flow wash, and 200 000 events were analysed using a Becton Dickinson FACS Canto II flow cytometer. The percentage of double-positive labelled cells was determined using dot-plot graphs and autofluorescence was assessed using untreated cells and control isotypes.

Experimental design

Four different protocols to demonstrate in vivo Eo antigen presentation were studied: re-stimulation of antigen-specific cells (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1a), stimulation of antigen-specific memory cells (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1b), priming of naive cells (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1c) and specific-immune response induction before C. neoformans-infection (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1d). For the re-stimulation of antigen-specific cells, eight rats/group were i.p. infected with 107 yeasts of C. neoformans for 5 days before i.p. inoculation for 5 more days of 2 × 106CnEo, unpulsed Eo, or PBS as controls. To perform the stimulation of antigen-specific memory cells, eight rats/group were i.p. infected with 107 yeasts of C. neoformans for 30 days before i.p. inoculation of 2 × 106CnEo, unpulsed Eo or PBS, for 5 further days. For the priming of naive cells, eight rats/group were i.p. inoculated for 15 days with 2 × 106CnEo, unpulsed Eo, or PBS. To perform a specific-immune response induction before C. neoformans-infection, eight rats/group were i.p. inoculated with 2 × 106CnEo, unpulsed Eo, or PBS for 10 days before i.p. infection with 107 yeasts of C. neoformans for 5 more days (this inoculum was chosen on the basis of our previous experience of establishing infection with this strain). Finally, the effects of these experimental designs on spleen and MLN responsiveness were studied.

In vivo eosinophil antigen presentation to spleen and MLN cells

Total spleen and MLN cells were obtained from treated rats, and spleens and MLN were pressed through wire-mesh screens to separate the cells. The erythrocytes were then lysed with a lysis buffer, pH 7·3. For some experiments, purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were obtained by incubating total lymph node cells for 30 min with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8a FITC-labelled antibodies, and then for 15 min more with anti-FITC MicroBeads. By positive selection (Miltenyi Biotec MACS, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) > 97% pure T cells were obtained with a viability of 98%.

The total spleen and MLN cells were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 antibodies, for 4 days at 37° and 5% CO2. After adding 1 μCi [3H]thymidine per well, the lymphocyte [3H]thymidine incorporation was determined 16–18 hr later, using a cell harvester and liquid scintillation counter.

Purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from spleen and MLN were labelled with CFSE, as described above for the Eo CFSE stain, and cultured with anti-CD3 antibodies. After 4 days at 37° and 5% CO2, cells were collected and 100 000 events were analysed using a Becton Dickinson FACS Canto II flow cytometer. The percentage of positive CFSE labelled cells was determined using logarithmic-scale histograms and dot-plot graphs.

Cytokine levels

The cytokine production by total spleen and MLN cells was measured in supernatants from 72-hr cultures. These cultures were performed in the presence or absence of heat-killed C. neoformans (HKC), as a specific stimulus (at a 1 : 1 ratio). The supernatants were collected and frozen to −70° until analysed. Interlukin-12p40, IFN-γ, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10 were measured using the ELISA sandwich CytoSets according to the manufacturer's protocol (Biosource). Dilutions of recombinant rat IL-12p40, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10 were used as standards. After washing, the plates were reacted with horseradish peroxidase streptavidin (Biosource), followed by the addition of tetramethylbenzidine for 5–20 min (Biosource), and the reaction was stopped with sulphuric acid. Measurements were obtained using a Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and results are expressed as pg/ml.

Nitrite measurement

Spleen and MLN cell NO production was measured. Cells were plated at a density of 106/ml in media on a 24-well plate with or without 106 HKC/ml. Then, nitrite accumulations, an indicator of NO production, were determined using Griess reagent.27 Briefly, 100-μl aliquots of 72-hr culture supernatants were mixed with an equal amount of Griess reagent and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The absorbance at 540 nm was measured using an automated microplate reader (Bio-Rad), and the concentration of nitrite was calculated from an NaNO2 standard curve.

Total specific-immunoglobulin ELISA

To determine the total C. neoformans-specific immunoglobulin levels, a sandwich ELISA was performed. Specific immunoglobulins were captured using glucuronoxylomannan (a C. neoformans-capsule polysaccharide) for adherence to the plates. Serial dilutions of 72-hr culture supernatants were carried out, followed by applications of peroxidase-A Protein (294 U/mg; Sigma), tetramethylbenzidine (Biosource) and sulphuric acid. The reaction was read at 450 nm on a Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad), and the results are expressed as optical density (OD).

Fungal burden

Evolution of cryptococcosis in the spleen and MLN was analysed by determining the colony-forming units (CFU) of C. neoformans per organ. The spleen and MLN of animals in the Protocol 4 group were removed under sterile conditions and homogenized in physiological solution with 50 mg/ml gentamicin. An aliquot of the homogenates from each animal was then inoculated onto Sabouraud glucose agar to determine the CFU after 3 days of incubation at 30°.34

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean + standard errors of the mean (SEM) and analysed statistically using the Student's t-test. Statistical significance was taken to be a P-value of < 0·05. All experiments were repeated and equivalent results were obtained.

Results

Intraperitoneally inoculated eosinophils migrate to the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes

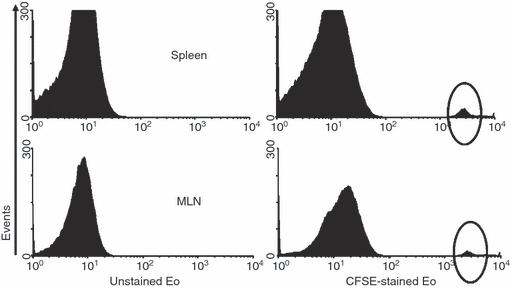

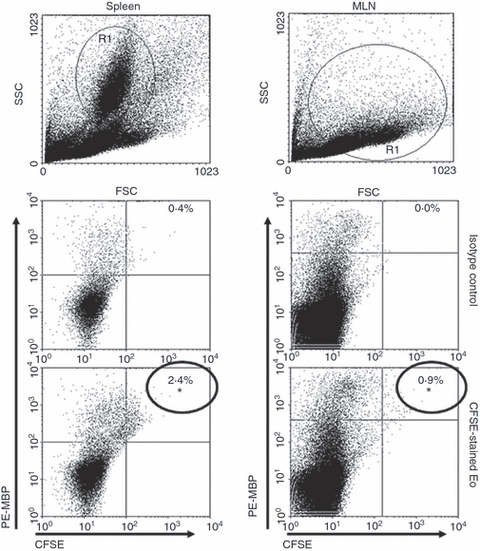

Five million CnEo, after being labelled with CFSE and resuspended in PBS, were inoculated i.p. into naive rats to assess their potential to migrate to the lymphoid organs. Spleens and MLN recovered from these rats, after 24–96 hr of inoculation, were made into single-cell suspensions and examined by flow cytometry for the presence of CFSE-labelled cells. Results showed the presence of CFSE-positive cells in MLN and spleen within 3 days of inoculation (Fig. 1). Then, using fluorescently labelled mAbs and FACS we performed an analysis to check that the CFSE-labelled cells were in fact Eo, and not another cell type that could phagocytose Eo (because of their possible death after inoculation) and carry them to the lymphoid organs. Results showed that all the CFSE-positive cells found in the spleen (2·4% in CFSE-stained Eo-inoculated rats versus 0·4% in control rats, P < 0·05) and MLN (0·9% in CFSE-stained Eo-inoculated rats versus 0·0% in control rats, P < 0·05) were definitely MBP positives (Fig. 2). In addition, no CFSE-labelled cells were positive for OX-62 (rat dendritic cell marker), CD11c (macrophage and dendritic cell marker), CD3 (T-cell marker) or CD45 (B-cell marker) (data not shown). Therefore, these results allowed us to conclude that CnEo are able to migrate to peritoneal lymphoid organs after their inoculation, but the way they use to migrate remains undefined.

Figure 1.

Migration of CFSE-labelled eosinophils (Eo) to lymphoid organs. Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) were inoculated intraperitoneally into naive rats. Spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) were recovered 72 hr later and evaluated for the presence of CFSE-labelled eosinophils by flow cytometry. The presence of CFSE-labelled cells was determined using logarithmic-scale histograms.

Figure 2.

The CFSE-labelled cells found in the lymphoid organs were definitively eosinophils (Eo). To assess this, 5 × 105 spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) cells were stained with phycoerythrin-labelled anti-rat CD3, CD45, CD11c, OX-62 and MBP, and 200 000 events were analysed by flow cytometry. The percentage of double-positive labelled cells was determined using dot-plot graphs, and data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (CFSE-stained Eo-inoculated rats versus normal rats). No CFSE-labelled cells were positive for OX-62, CD11c, CD3 or CD45.

In vivo C. neoformans-pulsed Eo induction of Th1 immune response by primed cells and B-cell stimulation

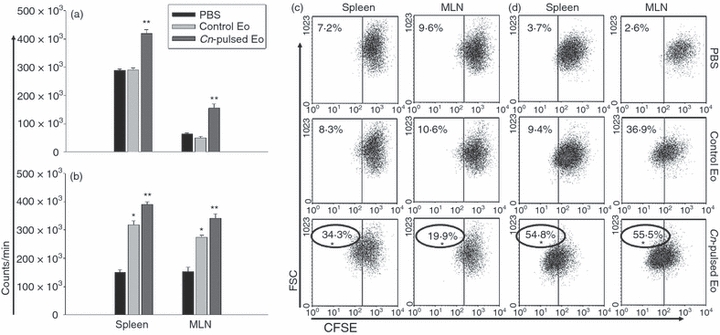

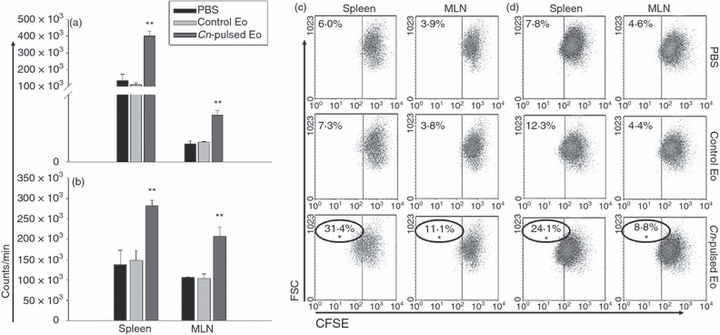

The CnEo were inoculated intraperitoneally into 5-day and 30-day C. neoformans-infected rats (protocols 1 and 2, respectively), to determine whether Eo could also stimulate antigen-specific T-cell proliferation in vivo as they were previously shown to do in vitro.23 After 5 days of inoculation, spleen and MLN cells recovered from these rats were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb to analyse the T-cell proliferation. Spleen and MLN cells of rats belonging to both protocol 1 (Fig. 3a) and protocol 2 (Fig. 3b), which were inoculated with CnEo, had an increased proliferation in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb compared with cells from untreated rats or cells from rats that had received unpulsed control Eo (a, P < 0·001 and b, P < 0·007). Next, the proliferative response of the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations from the lymphoid organs was analysed. Figure 3(c) (Protocol 1) and Fig. 3d (Protocol 2) show that T cells purified from 5-day and 30-day infected rats that had received CnEo proliferated in response to anti-CD3 mAb compared with control groups (P < 0·05), indicating that T cells were at least one of the populations responsible for the lymphoproliferation seen in CnEo-treated rats.

Figure 3.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) C. neoformans-specific cells to proliferate in vivo. Total spleen and MLN cells from rats belonging to protocols 1 (a) and 2 (b) were cultured, in the presence of anti-CD3 antibodies for 4 days. After adding 1 μCi [3H]thymidine per well, the lymphocyte [3H]thymidine incorporation was determined 16–18 hr later, using a cell harvester and liquid scintillation counter. Data are representative of three independent experiments. **P < 0·001 (Cn-pulsed Eo versus Eo) for (a), and *P < 0·0003 (Eo versus PBS) and **P < 0·007 (Cn-pulsed Eo versus Eo) for (b). Purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from spleen and MLN from rats belonging to protocols 1 (c) and 2 (d) were labelled with CFSE and cultured with anti-CD3 antibodies. After 4 days, cells were collected and 100 000 events were analysed by flow cytometry. The percentage of positive CFSE-labelled cells was determined using dot-plot graphs, and data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (Cn-pulsed Eo versus Eo).

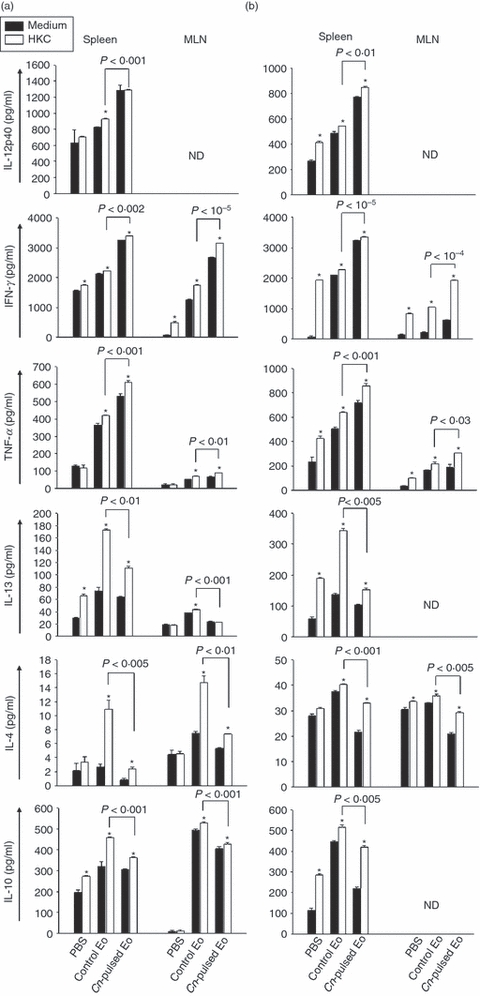

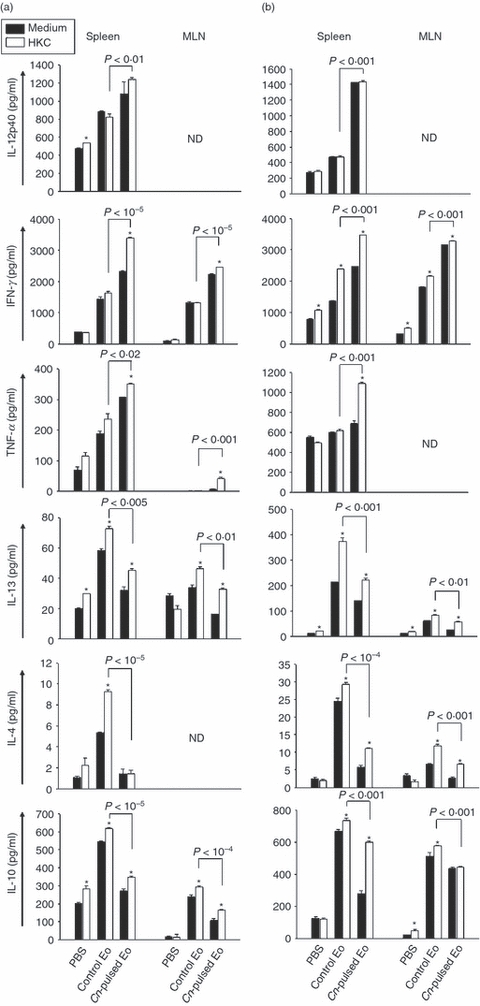

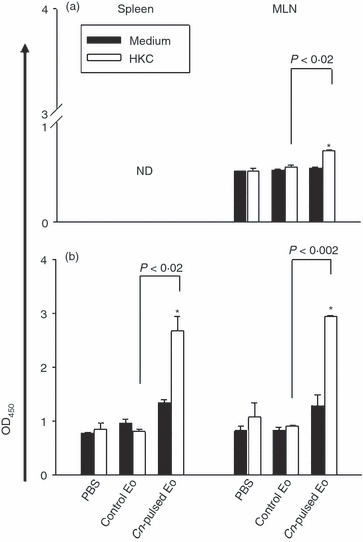

To evaluate the ex vivo fungicidal molecules and cytokine production by spleen and MLN cells of rats belonging to protocols 1 and 2, we decided to measured the NO synthesis by Griess reaction and the cytokine levels by ELISA in 72-hr cell culture supernatants. Figure 4 shows that the inoculation of CnEo into 5-day (a) and 30-day (b) infected rats increased NO production by spleen cells, compared with spleen cells of rats that had received unpulsed Eo after being infected (a) P < 0·004 and (b) P < 0·02, independent of the presence of HKC as a specific stimulus, but no NO production by MLN cells was detected. Furthermore, Fig. 5 shows that the inoculation of CnEo into 5-day (a) and 30-day (b) infected rats increased the spleen and MLN cell Th1 cytokine production, (for example, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α) compared with lymphoid organ cells of rats inoculated with unpulsed Eo after their infection (Fig. 5a, P < 0·001 for spleen IL-12, P < 0·002 for spleen IFN-γ, P < 10−5 for MLN IFN-γ, P < 0·001 for spleen TNF-α and P < 0·01 for MLN TNF-α; Fig. 5b, P < 0·01 for spleen IL-12, P < 10−5 for spleen IFN-γ, P < 10−4 for MLN IFN-γ, P < 0·001 for spleen TNF-α and P < 0·03 for MLN TNF-α) Moreover, these increases were more significant in the presence of HKC as a specific stimulus for C. neoformans-primed cells. On the other hand, the Th2 cytokine levels, such as IL-13, IL-4 and IL-10, were decreased in spleen and MLN cells (Fig. 5) from 5-day (a) and 30-day (b) infected rats that had been treated with CnEo, compared with control groups (Fig. 5a, P < 0·01 for spleen IL-13, P < 0·001 for MLN IL-13, P < 0·005 for spleen IL-4, P < 0·01 for MLN IL-4, P < 0·001 for spleen and MLN IL-10; Fig. 5b, P < 0·005 for spleen IL-13, P < 0·001 for spleen IL-4, P < 0·005 for MLN IL-4 and P < 0·005 for spleen IL-10), independent of the presence of HKC.

Figure 4.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen C. neoformans-specific cells to produce NO. Spleen cells from rats belonging to protocols 1 (a) and 2 (b) were plated for 72 hr at a density of 106/ml in media on a 24-well plate with or without 106 heat-killed C. neoformans (HKC)/ml. Nitrite accumulations, an indicator of NO production, were measured using the Griess reagent. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (medium versus HKC).

Figure 5.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) C. neoformans-specific cells to up-regulate T helper type 1 (Th1) type cytokines. Spleen and MLN cells from rats belonging to protocols 1 (a) and 2 (b) were cultured in medium alone or with heat-killed C. neoformans (HKC; at a 1 : 1 ratio). After 72 hr of culture, the interleukin-12p40 (IL-12p40), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α), IL-13, IL-4 and IL-10 production was measured in supernatants using ELISA capture kits. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (medium versus HKC).

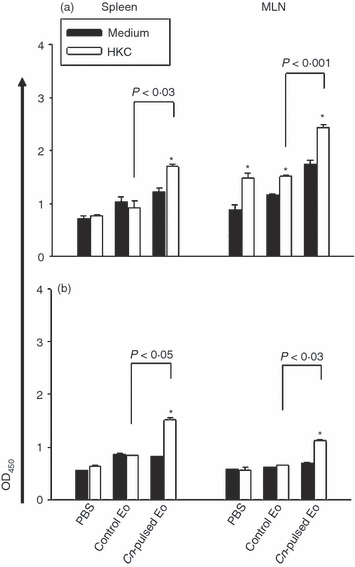

To analyse if spleen and MLN cells of 5-day and 30-day infected rats inoculated with CnEo were able to produce antigen-specific immunoglogulins ex vivo, an ELISA test was performed on 72-hr cell culture supernatants. Figure 6(a) (for protocol 1) and Fig. 6(b) (for protocol 2) show that the levels of total antigen-specific immunoglobulin in lymphoid organ cells of these animals cultured in the presence of HKC were significantly higher than in cells of infected rats inoculated with unpulsed Eo (Fig. 6a, P < 0·03 for spleen and P < 0·001 for MLN; Fig. 6b, P < 0·005 for spleen and P < 0·03 for MLN).

Figure 6.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) C. neoformans-specific cells to up-regulate total C. neoformans specific-immunoglobulin. Spleen and MLN cells from rats belonging to protocols 1 (a) and 2 (b) were cultured in medium alone or with heat-killed C. neoformans (HKC; at a 1 : 1 ratio). After 72 hr of culture, the total specific-immunoglobulin production was measured in supernatants using a sandwich ELISA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (medium versus HKC).

It was therefore concluded that CnEo are capable of migrating to the spleen and MLN of 5-day and 30-day C. neoformans-infected rats. Once there, they were able to stimulate lymphoid organ cell proliferation, thereby creating a Th1 microenvironment through the increase in Th1 cytokine production and the decrease in Th2 cytokine production. Moreover, they were able to stimulate NO synthesis in spleen cells and C. neoformans-specific immunoglobulin production in both spleen and MLN cells. In this regard, CnEo were able to stimulate antigen-specific cells in vivo to (i) induce a stronger Th1 immune response against a recent C. neoformans infection, and (ii) re-stimulate the specific-Th1 immune response against a nearly resolved C. neoformans infection.

Finally, the results observed show that the inoculation of unpulsed Eo into 30-day infected rats (protocol 2) stimulated the spleen and MLN cell proliferation, as was also shown in fungal-pulsed Eo, compared with untreated rats (Fig. 3b, P < 0·0003). In addition, unpulsed Eo (unlike CnEo) stimulated the increase of both Th1 and Th2 cytokine production in lymphoid organ cells from 5-day and 30-day infected rats (protocols 1 and 2, respectively) (Fig. 5a,b). These results allow us to speculate that Eo are capable of interacting with spleen and MLN cells, without being exposed to C. neoformans antigens, and can stimulate these cells to produce a wide spectrum of cytokines, so creating a mixed Th1 and Th2 microenvironment.

In vivo priming of naive cells by C. neoformans-pulsed eosinophils

Experiments were performed to analyse if Eo could prime naive lymphoid organ cells in vivo. In this regard, CnEo were inoculated intraperitoneally into naive rats (protocols 3), and after 15 days the spleen and MLN cells recovered from these rats were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb to evaluate T-cell proliferation. Lymphoid organ cells of rats inoculated with CnEo had an increased proliferation in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb, compared with cells from untreated rats or those from rats that had received unpulsed control Eo (Fig. 7a, P < 0·002). Moreover, Fig. 7(c) shows that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells purified from naive rats that had received CnEo proliferated more in response to anti-CD3 mAb compared with control groups (P < 0·05), indicating that T cells were at least one of the populations responsible for the lymphoproliferation seen in CnEo-treated rats.

Figure 7.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) naive cells to proliferate in vivo. Total spleen and MLN cells from rats belonging to protocols 3 (a) and 4 (b) were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 antibodies for 4 days. After adding 1 μCi [3H]thymidine per well, the lymphocyte [3H]thymidine incorporation was determined 16–18 hr later, using a cell harvester and liquid scintillation counter. Data are representative of three independent experiments. **P < 0·002 (Cn-pulsed Eo versus Eo) for (a) and **P < 10−4 (Cn-pulsed Eo versus Eo) for (b). Purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from spleen and MLN from rats belonging to protocols 3 (c) and 4 (d) were labelled with CFSE and cultured with anti-CD3 antibodies. After 4 days, cells were collected and 100 000 events were analysed by flow cytometry. The percentage of positive CFSE-labelled cells was determined using dot-plot graphs. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (Cn-pulsed Eo versus Eo).

The ex vivo fungicidal molecule and cytokine production by spleen and MLN cells from CnEo-treated naive rats were evaluated. Figure 8(a) shows that the inoculation of CnEo into naive rats increased the NO production in spleen cells cultured with HKC as a specific stimulus, compared with cells of rats that had received unpulsed Eo (P < 0·001). Again, no NO production by MLN cells was detected. Furthermore, Fig. 9(a) shows that the inoculation of CnEo into naive rats increased the spleen and MLN cell Th1 cytokine production, such as IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α, compared with lymphoid organ cells of rats inoculated with unpulsed Eo (P < 0·01 for spleen IL-12, P < 10−5 for spleen and MLN IFN-γ, P < 0·02 for spleen TNF-α and P < 0·001 for MLN TNF-α). As mentioned above, this increase was more significant in the presence of HKC as a specific stimulus for C. neoformans-primed cells. On the other hand, the Th2 cytokine levels, (for example, IL-13, IL-4 and IL-10), were decreased in spleen and MLN cells from CnEo-treated rats, compared with control groups (Fig. 9a, P < 0·005 for spleen IL-13, P < 0·01 for MLN IL-13, P < 10−5 for spleen IL-4, P < 10−5 for spleen IL-10 and P < 10−4 for MLN IL-10), independent of the presence of HKC.

Figure 8.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen naive cells to produce NO. Spleen cells from rats belonging to protocols 3 (a) and 4 (b) were plated for 72 hr at a density of 106/ml in media on a 24-well plate with or without 106 HKC/ml. Nitrite accumulations, an indicator of NO production, were measured using the Griess reagent. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 [medium versus heat killed C. neoformans (HKC)].

Figure 9.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) naive cells to up-regulate T helper type 1 (Th1) type cytokines. Spleen and MLN cells from rats belonging to protocols 3 (a) and 4 (b) were cultured in medium alone or with heat-killed C. neoformans (HKC; at a 1 : 1 ratio). After 72 hr of culture, the interleukin-12p40 (IL-12p40), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-13, IL-4 and IL-10 production was measured in supernatants using ELISA capture kits. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (medium versus HKC).

To investigate if spleen and MLN cells of naive rats inoculated with CnEo were able to produce antigen-specific immunoglobulin ex vivo, an ELISA test was performed in 72-hr cell culture supernatants. Figure 10(a) shows that the levels of total antigen-specific immunoglobulin in MLN cells of those animals cultured in the presence of HKC were significantly higher than in cells of rats inoculated with unpulsed Eo (P < 0·02). However, specific immunoglobulins were not detected in spleen cell culture supernatants.

Figure 10.

Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) promote spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) naive cells to up-regulate total C. neoformans specific-immunoglobulin. Spleen and MLN cells from rats belonging to protocols 3 (a) and 4 (b) were cultured in medium alone or with heat-killed C. neoformans (HKC; at a 1 : 1 ratio). After 72 hr of culture, the total specific immunoglobulin production was measured in supernatants using a sandwich ELISA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (medium versus HKC).

In conclusion, CnEo are capable of migrating to the spleen and MLN of naive rats and stimulating lymphoid organ cell proliferation, hence creating a Th1 microenvironment through the increase in Th1 cytokine production and the decrease in Th2 cytokine production. Moreover, these cells can stimulate NO synthesis by spleen cells and C. neoformans-specific immunoglobulin production by MLN cells. In this regard, CnEo may be able to stimulate naive cells in vivo to initiate a specific immune response against C. neoformans, which could be protective for subsequent infections with this fungus.

Treatment of rats with C. neoformans-pulsed eosinophils before infection results in a protective immune response against this fungus

Experiments were performed to analyse if the specific-immune response induced by CnEo in naive rats was able to protect these animals against C. neoformans infection. The CnEo were inoculated intraperitoneally into naive rats, and animals were infected with 107C. neoformans CFU 10 days after the inoculation (protocols 4). Finally, 5 days later, spleen and MLN cells recovered from these rats were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb to evaluate T-cell proliferation. Lymphoid organ cells of rats inoculated with CnEo before infection had an increased proliferation in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb, compared with cells from untreated rats or cells from rats that had received unpulsed control Eo (Fig. 7b, P < 10−4). Moreover, Fig. 7(d) shows that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells purified from rats that had received CnEo before infection had a greater proliferation in response to anti-CD3 mAb compared with control groups (P < 0·05), indicating that T cells were at least one of the populations responsible for the lymphoproliferation seen in CnEo-treated rats.

The ex vivo fungicidal molecule and cytokine production by spleen and MLN cells from CnEo-treated and infected rats were evaluated. Figure 8(b) shows that the treatment of rats with CnEo before infection increased NO production in spleen cells cultured with HKC as a specific stimulus, compared with cells of rats that had received unpulsed Eo (P < 0·001). Again, no NO production by MLN cells was detected. Furthermore, Fig. 9(b) shows that the treatment of rats with CnEo before infection increased the spleen and MLN cell Th1 cytokine production, such as IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α, compared with lymphoid organ cells of rats treated with unpulsed Eo before infection (P < 0·001 for spleen IL-12, P < 0·001 for spleen, MLN IFN-γ and P < 0·001 for spleen TNF-α). As mentioned above, this increase was more significant in the presence of HKC as a specific stimulus for C. neoformans-primed cells. On the other hand, the Th2 cytokine levels, such as IL-13, IL-4 and IL-10, were decreased in spleen and MLN cells from CnEo-treated rats before infection, compared with control groups (Fig. 9b, P < 0·001 for spleen IL-13, P < 0·01 for MLN IL-13, P < 10−4 for spleen IL-4, P < 0·001 for MLN IL-4, and P < 0·001 for spleen and MLN IL-10), independent of the presence of HKC.

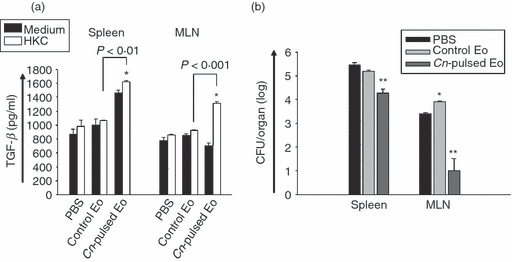

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) production by lymphoid organ cells was measured in 72-hr cell culture supernatants from all protocols. Differences in this cytokine were only detected when rats were treated with CnEo before infection (protocol 4), with an increase in production observed for fungal-pulsed Eo treatment, compared with control groups (Fig. 11a, P < 0·01 for spleen and P < 0·001 for MLN).

Figure 11.

The treatment of rats with Cryptococcus neoformans-pulsed eosinophils (Cn-pulsed Eo) before infection results in transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) production and reduced C. neoformans colony-forming units (CFU) in spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN). (a) Spleen and MLN cells from rats belonging to protocol 4 were cultured in medium alone or with heat-killed C. neoformans (HKC; at a 1 : 1 ratio). After 72 hr of culture, the TGF-β production was measured in supernatants using ELISA capture kits. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 (medium versus HKC). (b) Evolution of cryptococcosis in spleen and MLN was analysed by determining the CFU of C. neoformans per organ. The spleen and MLN of animals from protocol 4 were removed under sterile conditions and homogenized in physiological solution with 50 mg/ml of gentamicin. An aliquot of the homogenates from each animal was then inoculated onto Sabouraud glucose agar to determine the CFU after 3 days of incubation at 30°. *P < 0·05 (Eo versus PBS) and **P < 0·04 (Cn-pulsed Eo versus E×).

To analyse if the spleen and MLN cells of rats treated with CnEo before infection were able to produce antigen-specific immunoglobulin ex vivo, an ELISA test was performed on 72-hr cell culture supernatants. Figure 10(b) shows that the levels of total antigen-specific immunoglobulin in lymphoid organ cells of those animals cultured in the presence of HKC were significantly higher than in cells of rats treated with unpulsed Eo before infection (P < 0·02 for spleen and P < 0·002 for MLN).

To investigate if the treatment of rats with CnEo before infection resulted in a protective immune response against this fungus, the evolution of cryptococcosis in spleen and MLN was analysed by determining the CFU of C. neoformans per organ. Figure 11(b) shows that the spleen and MLN CFU of C. neoformans were reduced when rats were treated with CnEo before infection, compared with animals that had been treated with unpulsed Eo before being infected (P < 0·04 for spleen and MLN).

In conclusion, the specific-immune response induced by CnEo (characterized by a Th1 microenvironment, with increased NO synthesis and C. neoformans-specific immunoglobulin production) is able to protect rats against subsequent infection with the fungus.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to demonstrate the ability of Eo to present C. neoformans antigens in vivo, thereby priming naive and re-stimulating infected rats to induce T-cell and B-cell responses against infection with the fungus.

In comparison with other types of antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, the antigen-presenting cell function of Eo is presumably marginal. However, several properties of Eo probably combine to endow them with distinct roles as antigen-presenting cells. The first of these properties could be their tissue localization, with the normal localization of Eo within the mucosal tissues of the respiratory, gastrointestinal and lower genitourinary tracts35 positioning them to be able to encounter foreign antigens at these mucosal surfaces. Second, Eo have the capacity of transmigrating from the luminal surface of the mucosa into regional lymph nodes.19 Third, Eo are able to present antigens to naive and primed T cells in vitro21 and in vivo,22,36 thereby inducing an antigen-specific immune response.

In the initial experiments of the present study, using naive rats, it was shown that CnEo inoculated into the peritoneal cavity migrated to the spleen and MLN, but first, it was necessary to rule out the possibility that antigen-pulsed Eo may have died after injection into the peritoneum and might have later been phagocytosed by dendritic cells or macrophages. In this case, the antigens released from the antigen-pulsed Eo would then be presented by dendritic cells or macrophages to T cells and not by Eo themselves. Therefore, flow cytometry analysis was performed to demonstrate that the CFSE-labelled Eo definitely arrived at the spleen and MLN. Dot-plot graph results showed that all the CFSE-positive cells that were found in the spleen and MLN were positive for MBP (Fig. 2) and not for OX-62, CD11c, CD3 or CD45, indicating that Eo migrated to the peritoneal lymphoid organs after their inoculation. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies involving murine models, in which Eo were seen migrating from the airway lumina into regional lymph nodes, so providing a mechanism for antigens to be processed and transported into tissues for presentation to lymphocytes. These sensitized Eo, as they trafficked to regional lymph nodes, were shown to exhibit enhanced MHC II and lymphocyte co-stimulatory protein (CD80, CD86, CD40) expression,19,24 with these characteristics possibly allowing them to function in vivo as antigen-presenting cells to stimulate responses of T cells.

The present work also demonstrated that C. neoformans-pulsed Eo were capable of stimulating C. neoformans-specific cells to proliferate in vivo after inoculation into 5-day and 30-day fungus-infected rats (protocols 1 and 2, respectively). In this regard, Shi et al.19 established not only that endotracheal Eo homed to T-cell-rich regions of peritracheal lymph nodes, but also that these antigen-exposed Eo, when instilled into the airways of antigen-sensitized mice, were capable of stimulating T cell proliferative responses in vivo within the peritracheal lymph nodes. Moreover, the present study demonstrates that CnEo were able to stimulate naive cells to proliferate in vivo after their inoculation into naive rats (protocol 3). Related to this, by using green fluorescent protein transgenic Eo loaded with ovalbumin (OVA) covalently conjugated to blue fluorescent beads and CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 OVA T-cell receptor transgenic mice tagged with a red fluorochrome, Wang et al.36 visualized in situ the arrival of OVA-loaded Eo into the paratracheal lymph nodes and the physical interactions between Eo and naive OVA-specific CD4+ T cells. However, previous in vitro studies in our laboratory have shown that CnEo were able to stimulate the proliferative response of fungal-specific T cells but could not induce naive T cells to proliferate23 as we have recently demonstrated to occur in vivo. Referring to this, Yamamoto et al.37 have demonstrated that the transendothelial migration of human Eo, which takes place when bloodstream Eo enter tissues, increases Eo HLA-DR expression. Furthermore, Duez et al.24 have shown increased levels of MHC II expression in bronchoalveolar lavage Eo recovered from OVA-sensitized airway-challenged mice, with Eo MHC II being further up-regulated after Eo migration into draining lymph nodes. These observations may be showing the requirement of Eo migration into lymph nodes to enhance their functional role as antigen-presenting cells capable of priming naive cells.

The current study showed that the interaction of C. neoformans-pulsed Eo with fungal-primed and naive cells stimulated the production of the Th1 type cytokines IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α, and down-regulated the production of the Th2 type cytokines IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10. Moreover, the effect seen on Th1 and Th2 cytokine production was the most significant in the presence of HKC as a specific stimulus for C. neoformans-primed cells. In contrast, it has been previously demonstrated that antigen-loaded Eo present antigens to primed T cells and increase Th2 cytokine production.17,18 In addition, Eo pulsed with Strongyloides stercoralis antigen stimulated antigen-specific primed T cells and CD4+ T cells to increase IL-5 production.21,22 However, in a previous study, we demonstrated that mononuclear spleen cells and purified T cells isolated from spleens of C. neoformans-infected rats and cultured with C. neoformans-pulsed Eo proliferated in an MHC-I- and MHC-II-dependent manner, producing a large quantity of Th 1 type cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ, in the absence of Th2 cytokine synthesis.23 Related to this, it is well known that IL-12 and IFN-γ are essential for protection against C. neoformans infection.38–40 Furthermore, Th1 immune responses in C. neoformans infection models are characterized by the recruitment of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, production of Th1 cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12) and the formation of tight granulomas containing classically activated macrophages, which is followed by the clearance of the infection and its resolution.41 Although the Th2 immune responses were not found to be protective,42 in a pulmonary cryptococcosis developed in BALB/c mice, Huffnagle et al.43 observed that infiltrating T cells secreted significant amounts of Th2-type cytokines (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10) in addition to Th1-type cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2). These results suggested that the phenotype of T cells recruited into the lungs included a combination of Th1, Th2 and Th0 cells. However, the Th1 immune response must prevail over the Th2 response to obtain protection against C. neoformans infection.

In cryptococosis, the generation of NO by classically activated macrophages is required to produce resistance to fungal infections. Moreover, mice deficient in inducible nitric oxide synthase do not normally survive a primary infection.44 In the present study, the inoculation of CnEo into naive and infected rats stimulated the increase of NO production by spleen cells, independent of the presence of HKC as a specific stimulus, indicating that the treatment with antigen-pulsed Eo could have provided an NO dependent-protective mechanism against C. neoformans infection.

Although the role of humoral immunity in protection against C. neoformans infection has been difficult to establish, several studies have shown that administration of antibodies directed against the cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide can modify the course of the infection to the benefit of the host, by prolonging survival, clearing serum antigen, and in some cases, reducing the fungal burden.45 Moreover, another study has suggested that an effective anti-cryptococcal host immune response is associated with the predominance of ‘protective’ mAb isotypes (i.e. IgG1, IgG2a and IgG3b) against C. neoformans.46 In this regard, we have recorded an increase in the total antigen-specific immunoglobulin release by spleen and MLN cells of naive and infected rats inoculated with C. neoformans-pulsed Eo. We also demonstrated that fungal-pulsed Eo were able to stimulate not only T cells to proliferate and produce Th1 cytokines, but also that B cells could increase C. neoformans-specific immunoglobulin production.

To analyse if the specific immune response induced by C. neoformans-pulsed Eo in naive rats was able to protect animals against subsequent C. neoformans infection, naive rats were treated with fungal-pulsed Eo before being infected with 107 CFU of the fungus (protocol 4). The antigen-specific immune response induced by CnEo, which was characterized by the development of a Th1 microenvironment with increased levels of NO synthesis and C. neoformans-specific immunoglobulin production, was demonstrated to be able to protect rats against subsequent infection with C. neoformans, as observed by the CFU of the fungus on the spleen and MLN being significantly reduced in these rats. Moreover, TGF-β production was detected in lymphoid organ cells of rats treated with CnEo before infection. In fact, TGF-β is known to play both a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory role, depending on the stage of the immune response,47 with its pro-inflammatory influences including the promotion of T-cell migration,48 inhibition of activation-induced cell death49 and differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells.50 On the other hand, the anti-inflammatory actions are required to prevent prolonged inflammation that may be harmful to the host.47 Therefore, both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory actions of this cytokine are required for the development of a correct immune response.

Summing up, these experiments indicate that Eo can actively participate in priming the immune system for the required Th1 immune response as well as in the antibody-mediated humoral immune response against C. neoformans infection. Because of their capacity to contribute to the initiation (protocols 3 and 4) and amplification (protocols 1 and 2) of immune responses to C. neoformans antigens, the role of Eo as antigen-presenting cells may be important in mediating antigen-induced Th1 responses at the infection site, providing novel insights into the ability of this innate immune cell to function as an antigen-presenting cell by possibly contributing to the immune response that gives protection against C. neoformans infection.

Although the pathological significance of the model used is unknown and does not entirely mimic natural infection in which the lung is the portal of entry for C. neoformans yeasts, the i.p. infection is used to study the process of dissemination of the fungus, taking into account that this method of infection can develop a systemic infection, and not a local one,51 that in an immunocompetent animal is completely cleared at day 25 post-infection.3 Moreover, this model clearly supports the hypothesis that Eo, which have been shown to be components of the inflammatory response to C. neoformans infection in the rat lung,3,52 participate in the induction of the immune response to this infection.

Our findings do not diminish the roles played by natively resident dendritic cells and other cells such as macrophages, but rather establish that Eo, when recruited into the site of infection, may have additional functions as antigen-presenting cells and not only modulate an ongoing adaptive T-cell-mediated and B-cell-mediated immune response, but also initiate a protective immune response against C. neoformans infection.

Finally, in addition to the previously demonstrated abilities of CnEo in activating responses of fungal-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro, our studies show that CnEo act as professional antigen-presenting cells in vivo by fully activating and eliciting proliferation of naive cells, and also probably enhancing their cytokine synthesis in favour of a Th1-protective immune response against C. neoformans infection.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by grants from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 33326); Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de Argentina (PIP 6327); Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología (SeCyT), Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Grant 69/08); and Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Provincia de Córdoba (Grant 2008). A.P. Garro and J.L. Baronetti are PhD fellows of Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and L.S. Chiapello and D.T. Masih are members of the Research Career of Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas. We would like to thank native English speaker, Paul Hobson for revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Overview of experimental design. (A) For the re-stimulation of antigen-specific cells (Protocol 1), 8 rats/gorup were ip infected with 107 yeasts of C. neoformans for 5 days before ip inoculation of 2 × 106 CnEo, unpulsed Eo or PBS as controls for a further 5 days. (B) To perform the stimulation of antigen-specific memory cells (Protocol 2), 8 rats/group were ip infected with 107 yeasts of C. neoformans for 30 days before ip inoculation of 2 × 106 CnEo, unpulsed Eo or PBS for another 5 days. (C) For the priming of naive cells (Protocol 3), 8 rats/group were ip inoculated with 2 × 106 CnEo, unpulsed Eo or PBS for 15 days. (D) To test the specific-immune response induction before C. neoformans-infection (Protocol 4), 8 rats/group were ip inoculated with 2 × 106 CnEo, unpulsed Eo or PBS for 10 days before ip infection with 107 yeasts of C. neoformans for a further 5 days. IP: intraperitoneally, Cn: C. neoformans, Eo: eosinophils, LN: lymph nodes.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002;16:837–74. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldmesser M, Kress Y, Novikoff P, Casadevall A. Cryptococcus neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen in murine pulmonary infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4225–37. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4225-4237.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman D, Lee SC, Casadevall A. Pathogenesis of pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection in the rat. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4755–61. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4755-4761.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi M, Ito M, Sano K, Koyama M. Granulomatous and cytokine responses to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans in two strains of rats. Mycopathologia. 2001;151:121–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1017900604050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chensue SW, Warmington KS, Ruth JH, Lincoln P, Kunkel SL. Cytokine function during mycobacterial and schistosomal antigen-induced pulmonary granuloma formation: local and regional participation of IFN-γ, IL-10, and TNF. J Immunol. 1995;154:5969–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chensue SW, Ruth JH, Warmington K, Lincoln P, Kunkel SL. In vivo regulation of macrophage IL-12 production during type 1 and type 2 cytokine-mediated granuloma formation. J Immunol. 1995;155:3546–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chensue SW, Warmington K, Ruth JH, Lukacs N, Kunkel SL. Mycobacterial and schistosomal antigen-elicited granuloma formation in IFN-γ and IL-4 knockout mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:3565–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huffnagle GB, Yates JL, Lipscomb MF. Immunity to a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173:793–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huffnagle GB, Toews GB, Burdick MD, et al. Afferent phase production of TNF-α is required for the development of protective T cell immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 1996;157:4529–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe K, Kadota J, Ishimatsu Y, et al. Th1–Th2 cytokine kinetics in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans of different virulences. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:849–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovchik JA, Wilder JA, Huffnagle GB, Riblet R, Lyons CR, Lipscomb MF. Ig heavy chain complex-linked genes influence the immune response in a murine cryptococcal infection. J Immunol. 1999;163:3907–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoag KA, Street NE, Huffnagle GB, Lipscomb MF. Early cytokine production in pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infections distinguishes susceptible and resistant mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:487–95. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.4.7546779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy JW, Bistoni F, Deepe GS, et al. Type 1 and type 2 cytokines: from basic science to fungal infections. Med Mycol. 1998;36:109–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung Y-J, Woo S-Y, Jang MH, Miyasaka M, Ryu K-H, Park H-K, Seoh J-Y. Human eosinophils show chemotaxis to lymphoid chemokines and exhibit antigen presenting cell-like properties upon stimulation with IFN-γ, IL-3 and GM-CSF. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2008;146:227–34. doi: 10.1159/000115891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butterworth AE. The eosinophil and its role in immunity to helminth infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1977;77:127–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-66740-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. The eosinophil. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:147–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKenzie JR, Mattes J, Dent LA, Foster PS. Eosinophils promote allergic disease of the lung by regulating CD4+ Th2 lymphocyte function. J Immunol. 2001;167:3146–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie ZF, Shi HZ, Qin XJ, Kang LF, Huang CP, Chen YQ. Effects of antigen presentation of eosinophils on lung Th1/Th2 imbalance. Chin Med J. 2005;118:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi HZ, Humbles A, Gerard C, Jin Z, Weller PF. Lymph node trafficking and antigen presentation by endobronchial eosinophils. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:945–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI8945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi HZ. Eosinophils function as antigen-presenting cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:520–7. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0404228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padigel UM, Lee JJ, Nolan TJ, Schad GA, Abraham D. Eosinophils can function as antigen-presenting cells to induce primary and secondary immune responses to Strongyloides stercoralis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3232–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02067-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padigel UM, Hess JA, Lee JJ, et al. Eosinophils act as antigen-presenting cells to induce immunity to Strongyloides stercoralis in mice. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1844–51. doi: 10.1086/522968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garro AP, Chiapello LS, Baronetti JL, Masih DT. Rat eosinophils stimulate the expansion of Cryptococcus neoformans-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with a Th1 profile. Immunology. 2010;132:174–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duez C, Dakhama A, Tomkinson A, Marquillies P, Balhorn A, Tonnel AB, Bratton DL, Gelfand EW. Migration and accumulation of eosinophils toward regional lymph nodes after airway allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:820–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jose PJ, Griffiths-Johnson DA, Collins PD, et al. Eotaxin: a potent eosinophil chemoattractant cytokine detected in a guinea pig model of allergic airways inflammation. J Exp Med. 1994;179:881–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponath PD, Qin S, Ringler DJ, et al. Cloning of the human eosinophil chemoattractant, eotaxin. Expression, receptor binding, and functional properties suggest a mechanism for the selective recruitment of eosinophils. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:604–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI118456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi GR, Cervi LA, Garcia MM, Chiapello LS, Sastre DA, Masih DT. Involvement of nitric oxide in protecting mechanism during experimental cryptococcosis. Clin Immunol. 1999;90:256–65. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiapello L, Iribarren P, Cervi L, Rubinstein H, Masih DT. Mechanisms for induction of immunosuppression during experimental cryptococcosis. Role of glucuronoxylomannan. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:96–106. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiapello LS, Aoki MP, Rubinstein HR, Masih DT. Apoptosis induction by glucuronoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans. Med Mycol. 2003;41:347–53. doi: 10.1080/1369378031000137260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiapello LS, Baronetti JL, Aoki MP, Rubinstein HR, Masih DT. Immunosuppression, interleukin-10 synthesis and apoptosis are induced in rats inoculated with Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan. Immunology. 2004;113:392–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiapello LS, Baronetti JL, Garro AP, Spesso MF, Masih DT. Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan induces macrophage apoptosis mediated by nitric oxide in a caspase-independent pathway. Int Immun. 2008;20:1527–41. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedgwick JB, Shikama Y, Nagata M, Brener K, Busse WW. Effect of isolation protocol on eosinophil function: percoll gradients versus immunomagnetic beads. J Immunol Methods. 1996;198:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parish CR, Warren HS. Use of intracellular fluorescent dye CFSE to monitor lymphocytes migration and proliferation. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;9:1–10. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0409s84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubinstein HR, Sotomayor CE, Cervi LA, Riera CM, Masih DT. Immunosuppression in experimental cryptococcosis in rats: modification of macrophage functions by T suppressor cells. Macrophages functions in cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia. 1989;108:11–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00436778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rytömma T. Organ distribution and histochemical properties of eosinophil granulocytes in the rat. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1960;50:1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang HB, Ghiran I, Matthaei K, Weller PF. Airway eosinophils: allergic inflammation recruited professional antigen presenting cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:7585–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto H, Sedgwick JB, Vrtis RF, Busse WW. The effect of transendothelial migration on eosinophil function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:379–88. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.3.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawakami K, Qifeng X, Tohyama M, Qureshi MH, Saito A. Contribution of tumor necrosis factor-alfa (TNFα) in host defence mechanism against Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106:468–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aguirre K, Havell EA, Gibson GW, Johnson LL. Role of tumor necrosis factor and gamma interferon in acquired resistance to Cryptococcus neoformans in the central nervous system of mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1725–31. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1725-1731.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoag KA, Lipscomb MF, Izzo AA, Street NE. IL-12 and IFN-γ are required for initiating the protective Th1 response to pulmonary cryptococcosis in resistant C.B-17 mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:733–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.6.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen GH, McNamara DA, Hernandez Y, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB, Olszewski MA. Inheritance of immune polarization patterns is linked to resistance versus susceptibility to Cryptococcus neoformans in a mouse model. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2379–91. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01143-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernandez Y, Arora S, Erb-Downward JR, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Distinct roles for IL-4 and IL-10 in regulating T2 immunity during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:1027–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huffnagle GB, Lipscomb MF, Lovchik JA, Hoag KA. The role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the protective inflammatory response to a pulmonary cryptococcal infection. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:35–42. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aguirre KM, Gibson GW. Differing requirement for inducible nitric oxide synthase activity in clearance of primary and secondary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Med Mycol. 2000;38:343–53. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.5.343.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beenhouwer DO, Shapiro S, Felmesser M, Casadevall A, Scharff MD. Both Th1 and Th2 cytokines affect the ability of monoclonal antibodies to protect mice against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6445–55. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6445-6455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wormley FL, Jr, Perfect JR, Steele Ch, Cox GM. Protection against Cryptococcosis by using a murine gamma Interferon-producing Cryptococcus neoformans strain. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1453–62. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00274-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams AE, Humphreys IR, Cornere M, Edwards L, Rae A, Hussel T. TGF-beta prevents eosinophilic lung disease but impairs pathogen clearance. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:365–74. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams DH, Hathaway M, Shaw J, Burnett D, Elias E, Strain AJ. Transforming growth factor-beta induces human T lymphocyte migration in vitro. J Immunol. 1991;147:609–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buckley CD, Amft N, Bradfield PF, et al. Persistent induction of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by TGF-beta 1 on synovial T cells contributes to their accumulation within the rheumatoid synovium. J Immunol. 2000;165:3423–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Randolph GJ, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Liebman RM, Schakel K. The CD16+ (FcgammaRIII+) subset of human monocytes preferentially becomes migratory dendritic cells in a model tissue setting. J Exp Med. 2002;196:517–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benham RW. Cryptococci-their identification by morphology and by serology. J Infect Dis. 1935;57:255–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldman DL, Davis J, Bommarito F, Shao X, Casadevall A. Enhanced allergic inflammation and airway responsiveness in rats with chronic Cryptococcus neoformans infection: potential role for fungal pulmonary infection in the pathogenesis of asthma. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1178–86. doi: 10.1086/501363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.