Abstract

Ca2+ channels regulate many crucial processes within cells and their abnormal activity can be damaging to cell survival, suggesting that they might represent attractive therapeutic targets in pathogenic organisms. Parasitic diseases such as malaria, leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis and schistosomiasis are responsible for millions of deaths each year worldwide. The genomes of many pathogenic parasites have recently been sequenced, opening the way for rational design of targeted therapies. We analyzed genomes of pathogenic protozoan parasites as well as the genome of Schistosoma mansoni, and show the existence within them of genes encoding homologues of mammalian intracellular Ca2+ release channels: inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), ryanodine receptors (RyRs), two-pore Ca2+ channels (TPCs) and intracellular transient receptor potential (Trp) channels. The genomes of Trypanosoma, Leishmania and S. mansoni parasites encode IP3R/RyR and Trp channel homologues, and that of S. mansoni additionally encodes a TPC homologue. In contrast, apicomplexan parasites lack genes encoding IP3R/RyR homologues and possess only genes encoding TPC and Trp channel homologues (Toxoplasma gondii) or Trp channel homologues alone. The genomes of parasites also encode homologues of mammalian Ca2+ influx channels, including voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and plasma membrane Trp channels. The genome of S. mansoni also encodes Orai Ca2+ channel and STIM Ca2+ sensor homologues, suggesting that store-operated Ca2+ entry may occur in this parasite. Many anti-parasitic agents alter parasite Ca2+ homeostasis and some are known modulators of mammalian Ca2+ channels, suggesting that parasite Ca2+ channel homologues might be the targets of some current anti-parasitic drugs. Differences between human and parasite Ca2+ channels suggest that pathogen-specific targeting of these channels may be an attractive therapeutic prospect.

Introduction

Parasitic diseases collectively affect billions of people and cause millions of deaths worldwide each year ( Table 1 ). Many parasitic diseases are caused by single-celled protozoa such as various species of the apicomplexan parasites Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, Cryptosporidium and Babesia, as well as several species of the kinetoplastid Trypanosoma and Leishmania parasites. Other parasitic protozoa that are major contributors to worldwide disease include Trichomonas vaginalis, Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia intestinalis. Another major cause of human disease and mortality, second only to malaria amongst parasitic diseases, is the Schistosoma family of parasitic blood flukes. Many of these parasites maintain stringent control over their intracellular Ca2+ concentration [1], [2] and have been shown to exhibit Ca2+ signals in response to physiological stimuli. These Ca2+ dynamics are critical for parasite function, egress, invasion, virulence and survival [2]–[4]. However, the molecular basis for these parasite Ca2+ responses is largely unknown.

Table 1. Pathogenic parasites with completed whole-genome sequences, their associated diseases and worldwide disease burden.

| Parasite | Disease | Estimated worldwide cases of infection | Genome References |

| Plasmodium falciparum Plasmodium knowlesi Plasmodium vivax | malaria | 3 billion [103], [126] | [127]–[130] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | toxoplasmosis | 6–75% of population [131] | [132] |

| Cryptosporidium hominis Cryptosporidium muris Cryptosporidium parvum | cryptosporidiosis, diarrhoea | 1–20% of population [131], [133] | [134]–[136] |

| Babesia bovis | babesiosis | humans: >500cattle: 400 million | [137] |

| Leishmania major Leishmania infantum Leishmania braziliensis | leishmaniasis | 12 million [131] | [138]–[140] |

| Trypanosoma brucei | african trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) | 500,000 | [141] |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | Chagas' disease | 10 million | [142] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | amoebiasis, dysentry | 50 million [131] | [143] |

| Giardia intestinalis | giardiasis | 280 million [144] | [145]–[148] |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | trichomoniasis | 174 million [149] | [150] |

| Schistosoma mansoni | schistosomiasis (bilharzia) | 200 million | [121] |

World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/en) and Center for Disease Control (http://www.cdc.gov) figures, in addition to the references cited, were used as sources of worldwide epidemiology.

Ca2+ release via intracellular Ca2+ channels controls numerous cellular processes, ranging from receptor signalling to growth and apoptosis [5]. Four main families of these channels have been identified in mammals: inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), ryanodine receptors (RyRs), two-pore channels (TPCs), and some transient receptor potential (Trp) channels. Mammalian IP3Rs and RyRs are responsible for release of Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in response to the intracellular messengers IP3 and Ca2+ (IP3Rs), or cyclic ADP ribose (cADPR) and Ca2+ (RyRs), produced via a wide variety of cellular signalling pathways [6], [7]. The recently described TPCs are nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-activated channels responsible for Ca2+ release from acidic organelles, including lysosomes [8], [9]. Mammalian intracellular Trp channels such as TrpM, TrpML and TrpP2 (polycystin-2) have also been shown to play a role in release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores [10], [11]. Many parasites possess intracellular Ca2+ stores within their ER, mitochondria, glycosomes and acidocalcisomes [2], [3], [12], [13], but whether channels homologous to mammalian intracellular Ca2+ channels are present in these parasite organelles and whether they mediate Ca2+ release are unknown.

Ca2+ entry in mammalian cells is mediated by plasma membrane Ca2+ channels such as voltage-gated Ca2+ (Cav) channels [14], Trp channels [11] and store-operated Orai channels [15]. These channels are essential components in a multitude of signalling pathways and are also required for refilling of intracellular Ca2+ stores following intracellular Ca2+ release. Mechanisms of Ca2+ influx and demand for it are likely to differ between life cycle stages of many parasites, due to the differential ionic conditions of their respective environments. The intracellular location of many protozoan parasites during part of their life cycles [16], where Ca2+ concentrations in the mammalian host cell are maintained at low levels, suggests that novel Ca2+ entry pathways may be essential for parasite survival. In the extracellular trematode parasite S. mansoni, Ca2+ influx channels are important for muscle contraction and viability [17]. However, apart from the cloning of three S. mansoni Cav channels [18] and a report of Trp channels in various parasites [19], the identities of plasma membrane Ca2+ influx channels in pathogenic parasites remain largely unknown.

Pharmacological or genetic modulation of Ca2+ channel activity in the plasma membrane or intracellular organelles has profound effects on cell function and survival in many organisms. This suggests that the channels underlying Ca2+ signals in parasites might represent novel drug targets. Recent advances in genomics have led to whole-genome sequencing of several parasites that are pathogenic to humans ( Table 1 ). In this study we examined the genomes of pathogenic parasitic protozoa, and that of S. mansoni, for the presence of genes that might encode Ca2+ channels in either the plasma membrane or intracellular organelles. We show that genes encoding homologues of mammalian intracellular Ca2+ channels and plasma membrane Ca2+ influx channels exist in many of these parasites. Some currently used anti-parasitic agents alter Ca2+ homeostasis in parasites, and some are also direct modulators of mammalian Ca2+ channels (see Discussion). This suggests that the parasite Ca2+ channel homologues described in this study might be the targets for some anti-parasitic drugs. Sequence divergence of parasite channels from their mammalian counterparts in regions that are important for channel activation, ion conduction or drug binding may result in distinct pharmacological profiles. These parasite channels may therefore represent attractive novel targets for rationally designed anti-parasitic therapies.

Results

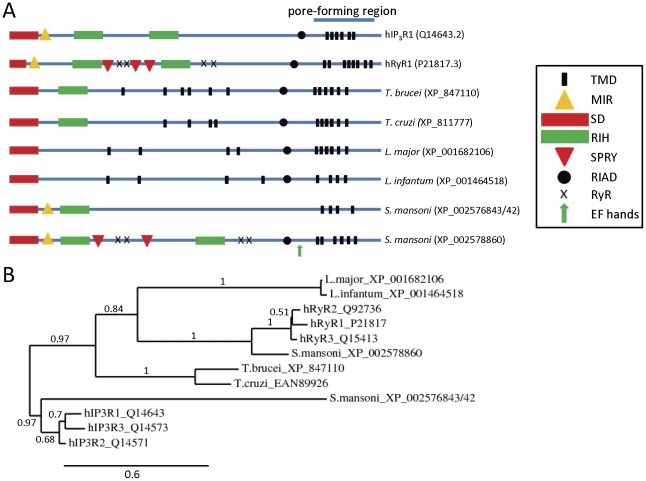

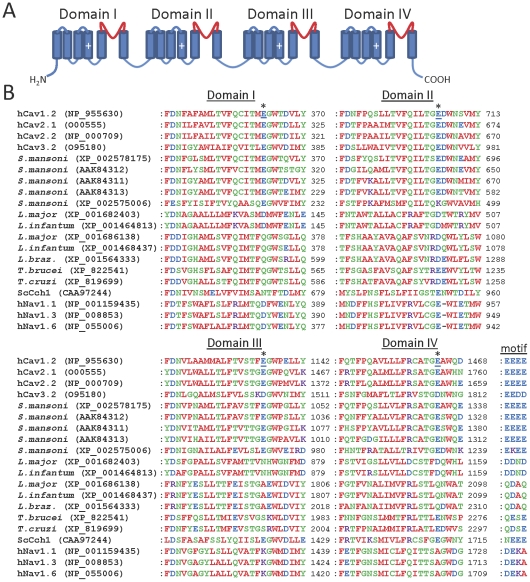

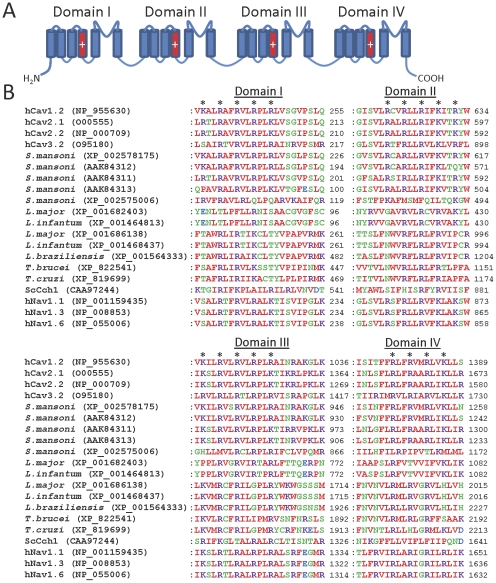

Parasite homologues of IP3R and RyR pores

Mammalian IP3Rs and RyRs show a high degree of similarity, particularly in the pore region responsible for ion conduction. BLAST analysis of the conserved pore-region sequences of mammalian IP3Rs and RyRs against the whole-genome sequences of pathogenic parasites identified several predicted protein products displaying significant similarity in this pore region ( Figure 1 and Table 2 ). These homologues were found in the kinetoplastid Leishmania and Trypanosoma parasites, as well as in S. mansoni. In contrast to the multiple isoforms of IP3R and RyR found in vertebrates [7], [20], each species of Trypanosoma and Leishmania parasite possessed only a single homologue. In contrast, S. mansoni possessed two homologues: one similar to mammalian IP3Rs (XP_002576843/42 in Figure 1 ), which showed 34% identity with human IP3R3 (hIP3R3) and 31% identity with human RyR1 (hRyR1) in the full-length proteins; and one more similar to mammalian RyRs (XP_002578860), which showed 45% identity with hRyR2 and 32% identity with hIP3R1 ( Figure 1 ). No IP3R/RyR homologues (of either pore or full-length sequences) were found in the genomes of any of the apicomplexan parasites, or in the protozoan parasites E. histolytica, G. intestinalis and T. vaginalis.

Figure 1. Alignment of parasite putative IP3Rs/RyRs with the pore regions of mammalian IP3Rs/RyRs.

Alignments of the pore region of human IP3Rs and RyRs with putative homologues from T. brucei, T. cruzi, L. infantum, and S. mansoni. ClustalW2 physiochemical residue colours are shown, and protein accession numbers are shown in parentheses after the species name. Numbers in parentheses to the right of the alignments indicate the total number of residues in the protein. Asterisks below the alignment indicate absolute residue conservation in all homologues. Triangles below the alignment indicate the position of residues discussed in the text (G4891, R4893 and Q4934 of hRyR1). The blue bar above the alignment indicates the selectivity filter region, while the red bar indicates the pore-forming transmembrane domain (TMD). The S. mansoni protein labelled XP_002576843/42 is formed by concatenated XP_002576843 and XP_002576842 predicted proteins (whose genomic loci are adjacent). The entire concatamer was confirmed as a single intact protein by its identity with the predicted protein: 29191.m000804.twinscan2 (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK).

Table 2. Identity of Ca2+ channel homologues in pathogenic parasites.

| Parasite | IP3Rs/RyRs | TPCs | Trp channels | Cav channels |

| P. falciparum | NF | NF | XP_001349872 (TrpML/TrpP) (14)a | NF |

| P. knowlesi | NF | NF | XP_002262030 (TrpML/TrpP) (14)a | NF |

| P. vivax | NF | NF | XP_001617062 (TrpML/TrpP) (12)a | NF |

| T. gondii | NF | XP_002364352 (15) | XP_002367104 (TrpP) (14) XP_002364302 (TrpP) (19) | XP_002370025 (6) XP_002367758 (2) XP_002367759 (11) XP_002368840 (12) |

| C. hominis | NF | NF | XP_668155 (TrpC/TpP/TrpV) (6) XP_667205 (TrpP) (13) | NF |

| C. muris | NF | NF | XP_002140701 (TrpC/TrpP) (8)XP_002139610 (TrpP) (17) | NF |

| C. parvum | NF | NF | XP_627518 (TrpC/TrpP/TrpV) (8) XP_627866 (TrpP) (13) | NF |

| B. bovis | NF | NF | NF | XP_001611701 (6) |

| L. major | XP_001682106 (10) | NF | XP_001681002 (TrpML) (6) XP_001684103 (TrpML/TrpP) (4) | XP_001682403 (21) XP_001686138 (24) |

| L. infantum | XP_001464518 (8) | NF | XP_001463306 (TrpML) (7) XP_001470439 (TrpML/TrpP) (7) | XP_001464813 (19) XP_001468437 (22) |

| L. braziliensis | NF | NF | NF | XP_001564333 (22) XP_001563925 (10) |

| T. brucei | XP_847110 (12) | NF | XP_845719 (TrpML/TrpP) (6)XP_846922 (TrpC/TrpP/TrpML) (6) | XP_822541 (22) |

| T. cruzi | XP_811777 (10) | NF | XP_804976 (TrpML/TrpP) (7)XP_804854 (TrpML/TrpP) (5)XP_816280 (TrpML/TrpP) (6)XP_807515 (TrpML/TrpP) (6) | XP_819699 (24) |

| T. vaginalis | NF | NF | XP_001325681 (TrpML/TrpP) (6) XP_001298159 (TrpML) (6) XP_001296819 (TrpV) (6) | NF |

| S. mansoni | XP_002576843/42 (IP3R) (4)XP_002578860 (RyR) (6) | XP_002578810 (4) | XP_002579262 (TrpML) (7) XP_002575977(TrpM) (7) XP_002570040 (TrpM) (9) XP_002579093(TrpM) (4) XP_002571459(TrpM) (4) XP_002573069(TrpM) (6) XP_002578456(TrpM/TrpC) (5)XP_002578457 (TrpM) (2) XP_002582108 (TrpM/TrpC/TrpV) (6) XP_002578454 (TrpM) (2) XP_002577419 (TrpP) (8) XP_002579176 (TrpP) (6) XP_002579107 (TrpP) (16) XP_002572123 (TrpA) (4) XP_002576849 (TrpC) (7) XP_002576118 (TrpC) (8) XP_002579731 (TrpC) (8) XP_002578785 (TrpC) (6) XP_002570832 (TrpC) (2) | XP_002578175 (20) XP_002575006 (18)AAK84311 (Cav2A) (24) AAK84312 (Cav1) (22) AAK84313 (Cav2B) (20) XP_002571932 (18)b |

Protein accession numbers for homologues are shown. Trp channel homologues were identified by homology with the transmembrane region of at least one class of mammalian Trp channel. Trp channels were then annotated according to the classes of mammalian Trp channel to which the full-length protein showed the greatest sequence similarity in BLASTP searches of the human genome (shown in parentheses for Trp channel homologues). Cav homologues include both human Cav channel and S. cerevisiae Cch1 homologues. The S. mansoni protein labelled XP_002576843/42 is formed by concatenated XP_002576843 and XP_002576842 predicted proteins (whose genomic loci are adjacent). The entire concatamer was confirmed as a single intact protein by its identity with the predicted protein: 29191.m000804.twinscan2 (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK). The number of predicted transmembrane domains (TMDs) present in homologues is indicated in parentheses. In addition to the Ca2+ channel homologues shown, a homologue of the store-operated Ca2+ influx channel Orai1 was found in S. mansoni: XP_002578837 (with shorter splice variant XP_002578838). Homologues of the very recently identified mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter [124], [125] were also found in Leishmania and Trypanosoma spp. (eg. XP_822290 of T. brucei), as well as S. mansoni (XP_002569737), but were absent from the other parasites examined (data not shown). PM denotes plasma membrane and NF denotes no homologues found.

Identified by homology with T. gondii protein XP_002367104;

Possible Cav2B fragment, incomplete sequence available.

Structures of parasite IP3R and RyR homologues

Although the Leishmania, Trypanosoma and S. mansoni parasite proteins show a high degree of sequence similarity to IP3Rs/RyRs in the pore region, it was necessary to examine similarity in other regions before establishing them as potential functional correlates. Defining characteristics of vertebrate IP3Rs and RyRs include their large size (∼5000 residues for RyRs and ∼2700 residues for IP3Rs) and the presence of: multiple transmembrane domains near their C-terminal ends, conserved N-terminal MIR (mannosyltransferase, IP3R and RyR) domains, conserved RIH (internal RyR and IP3R homology) sequences with homology to the IP3-binding core of IP3Rs [21], conserved “RIH-associated domains” preceding their C-terminal transmembrane regions, and conserved N-terminal domains with homology to the suppressor domain of IP3Rs [22] ( Figure 2A ). Mammalian RyRs are also distinguished by the presence of multiple copies of a repeat termed an SPRY (SPla and RyR) domain and multiple copies of a repeat termed a RyR domain, both of which have unknown functions.

Figure 2. Comparison of full-length sequences of human and parasite IP3R/RyR homologues.

(A) Schematic showing location of putative transmembrane domains (TMDs) and conserved domains identified using the Conserved Domains Database (NCBI), including: MIR (mannosyltransferase, IP3R and RyR) domains (pfam02815), RIH (RyR and IP3R homology) domains (pfam01365), RIH-associated domains (RIAD) (pfam08454), EF hands, suppressor-domain-like domains (SD) (pfam08709), RyR (ryanodine receptor) domains (pfam02026), and SPRY (SPla and the ryanodine receptor) domains (pfam00622). Putative pore-forming regions (pfam00520) are also indicated. (B) Phylogram showing relationships between full-length sequences of human and parasite IP3R/RyR homologues (see Methods: based on 226 high confidence positions from a multiple sequence alignment; gamma shape parameter 1.755; proportion of invariant sites 0). Branch length scale bar and branch support values are shown.

The parasite IP3R/RyR pore homologues are large proteins (2216-4998 residues) ( Figure 1 ). The S. mansoni IP3R-like and RyR-like homologues are 2216 and 4998 residues in length, and phylogenetic analyses are consistent with these proteins representing IP3R and RyR homologues respectively ( Figure 2B ). Significantly, most homologues have predicted N-terminal RIH domains ( Figure 2A ), and searches of parasite genomes using the N-terminal IP3-binding domain sequence of mammalian IP3Rs (residues 224–604 of rat IP3R1) resulted in alignment with the same Leishmania, Trypanosoma and S. mansoni proteins found in the pore homology search. However, alignments suggested that like RyRs, the parasite homologues lack many of the ten basic residues known to be important for high-affinity binding of IP3 to mouse IP3R1 [23] (data not shown). The S. mansoni protein (XP_002576843/42), which has the greatest sequence similarity to full-length human IP3Rs, also has the highest conservation of these basic residues (5 out of 10) (data not shown). All parasite homologues are predicted to contain multiple putative transmembrane domains near their C-termini, and to contain N-terminal domains with similarity to the suppressor domain of mammalian IP3Rs and the analogous A-domain of RyRs [22] ( Figure 2A ). In addition, most homologues have N-terminal RIH-associated sequences ( Figure 2A ). Both S. mansoni homologues have N-terminal MIR domains, while the S. mansoni RyR homologue, like mammalian RyRs, has four copies of a RyR motif and multiple copies of an SPRY domain ( Figure 2A ). Several consensus Ca2+-binding EF-hands are also present in the C-terminus of the S. mansoni RyR homologue ( Figure 2A ), suggesting that this channel, like mammalian IP3Rs and RyRs, might be regulated by cytosolic Ca2+. Taken together, these sequence similarities suggest that these parasite channels are structural and functional analogues of mammalian IP3Rs and RyRs.

The close similarity of the pore regions of parasite channels to those of mammalian IP3Rs/RyRs, including the conserved GGGXGD selectivity filter motif ( Figure 1 ) suggests that these parasite channels are likely to form cation channels with high single-channel conductance and permeability to Ca2+. Despite this significant similarity, parasite homologues show some potentially important sequence divergence from human IP3Rs/RyRs in the pore region ( Figure 1 ). For example, both Leishmania homologues and the S. mansoni IP3R-like homologue differ from human IP3Rs/RyRs near the selectivity filter region, at positions analogous to hRyR1 residues G4891 and R4893 that are known to affect ryanodine binding [24]. Also, all parasite homologues (except the S. mansoni RyR homologue) differ from human RyRs in the pore-lining transmembrane domain, at the position analogous to Q4934 of hRyR1, which is a determinant of ryanodine binding [25]. Some pathogenic parasites therefore possess homologues of both IP3Rs and RyRs in which key functional domains are well enough conserved to suggest that these proteins might function as intracellular Ca2+ channels. However, the sensitivity of these parasite channels to drugs may differ sufficiently from those of their host to perhaps allow their selective targeting by drugs.

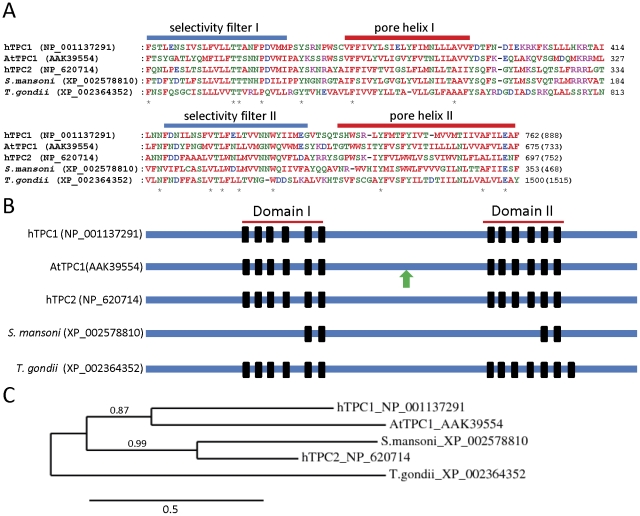

TPC homologues

We searched next for parasite homologues of mammalian TPCs, which mediate release of Ca2+ from acidic organelles in mammalian cells. A defining characteristic of both mammalian and plant TPCs is the presence of two independent pore-forming domains in series, each consisting of multiple transmembrane domains [8], [9], [26], [27]. We therefore searched parasite genomes, using the full-length sequences of human TPC1 and TPC2, for homologues that contained at least four transmembrane domains in two distinct regions. Reciprocal BLAST searches were then carried out with sequences of the identified parasite proteins, to confirm specific homology with mammalian TPCs. This approach identified TPC homologues in only S. mansoni and T. gondii ( Figures 3A and 3B ). These parasite homologues show substantial similarity to mammalian TPCs in the pore regions responsible for ion conduction ( Figure 3A ) suggesting that they, like their mammalian counterparts, may act as Ca2+-permeable channels. The S. mansoni homologue shows most similarity to human TPC2, while the T. gondii homologue is more distantly related to mammalian TPCs ( Figure 3C ). Interestingly, the S. mansoni TPC homologue has only two predicted transmembrane segments in each of its pore domains, compared to the six found in each domain of mammalian TPCs [8], [9], [26], [27]. The sequences of plant TPC (Arabidopsis thaliana, AtTPC1) as well as the S. mansoni and T. gondii TPC homologues themselves were then used to search for additional parasite homologues, but none were identified. The parasite TPC homologues identified here lack the EF-hand repeat found in plant AtTPC1 channels ( Figure 3B ), suggesting that like mammalian TPCs, parasite TPC homologues may be Ca2+-insensitive.

Figure 3. Comparison of human, plant and parasite TPC homologues.

(A) Alignments of pore domains I (upper panel) and II (lower panel) of human, plant (AtTPC1 is Arabidopsis thaliana TPC1) and parasite TPC homologues. Asterisks below the alignment indicate absolute residue conservation in all homologues. (B) Schematic showing the location of transmembrane domains (black bars) within the full-length sequences of human, plant and parasite TPC homologues. The green arrow signifies an EF-hand repeat in AtTPC1. (C) Phylogram showing the relationship between full-length sequences of human, plant and parasite TPC homologues (see Methods: based on 220 high confidence positions from a multiple sequence alignment; gamma shape parameter 4.195; proportion of invariant sites 0.021). Branch length scale bar and branch support values are shown.

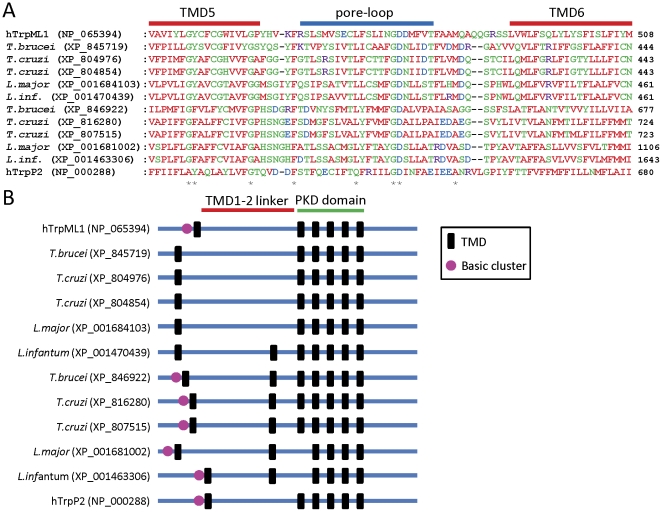

Intracellular Trp channel homologues

In addition to IP3Rs, RyRs and TPCs, several subtypes of mammalian Trp channel are located within the membranes of intracellular organelles and mediate Ca2+ release in mammalian cells. These include TrpM, TrpML, and TrpP2 channels [10], [11], [28]. We therefore searched parasite genomes for homologues of these Trp channels, using the full-length and N-terminally truncated (to remove common ankyrin domains) sequences of human isoforms, followed by further searches using the sequences of identified homologues from T. gondii. We identified many parasite homologues of these Trp channels ( Table 2 ). Putative Trp channel homologues in Plasmodium spp. were only identified by homology with a T. gondii Trp channel homologue, and show only weak similarity to mammalian Trp channels. Overall, these results are consistent with a recent report of Trp channels in various parasites [19], although we describe here additional putative homologues in Plasmodium spp., T. gondii, T. vaginalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Trypanosoma spp. and S. mansoni ( Table 2 ). Definitive categorization of homologues as subtypes of Trp channel was difficult, as multiple homologies existed between these proteins. Homologues were therefore categorized by reference to the human Trp channels to which they showed the greatest sequence similarity ( Table 2 ). TrpML and TrpP homologues were found in most parasites examined, while TrpM channel homologues were found only in S. mansoni ( Table 2 ). We were most interested in the TrpML/TrpP homologues found in kinetoplastid parasites, which show considerable similarity to human TrpML and TrpP2 channel subunits in the putative pore region ( Figure 4A ). They also have conserved predicted polycystin (PKD) domains and long TMD1-TMD2 linkers that are characteristic of TrpML and TrpP channel subunits ( Figure 4B ). In addition, several of these parasite proteins have a cluster of basic residues preceding their TMD1 regions, similar to the cluster responsible for binding phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2) in mouse TrpML1 [29] ( Figure 4B ). The Trp channel homologue Yvc1p (TrpY1) is responsible for mediating Ca2+ release from vacuolar stores of Saccharomyces cerevisiae [30], [31]. We therefore searched parasite genomes for homologues of full-length Yvc1p, but none were found.

Figure 4. Trp channel homologues in kinetoplastid parasites.

(A) Alignment of the pore regions of human TrpML and TrpP2 channel subunits with putative homologues from kinetoplastid parasites. Sequences of the putative pore loops as well as part of the TMD5 and TMD6 regions are shown. Numbers in parentheses to the right of the alignments indicate the total number of residues in the protein. Asterisks below the alignment indicate residues that are absolutely conserved between parasite proteins and either hTrpML1 or hTrpP2. L. infantum is shown abbreviated to L. inf. (B) Schematic showing the location of predicted TMDs (black bars) within the full-length sequences of human TrpML1 and TrpP2 channel subunits, as well as parasite homologues. The conserved PKD polycystin domain (pfam08016; identified using the Conserved Domains Database, NCBI) is indicated, as well as the long TMD1-TMD2 linker characteristic of mammalian TrpML and TrpP2 channel subunits. The presence of an N-terminal cluster of basic residues preceding TMD1 is indicated by a purple circle.

Plasma membrane Trp channel homologues

Ca2+-permeable Trp channels located in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells include TrpC, TrpA, TrpV and TrpP subtypes [11], [28]. TrpC channels may contribute to store-operated Ca2+ entry in many cells [32], TrpA and TrpV channels respond to external chemical and thermal stimuli [11], and TrpP2 channels at the plasma membrane respond to stimuli including mechanical stress and receptor activation [33]. We searched parasite genomes for homologues of these Trp channels, using the full-length and N-terminally truncated (again, to remove ankyrin domain hits) sequences of human isoforms, and identified several parasite homologues ( Table 2 ). The protozoan parasite genomes examined were found to lack homologues of TrpA and TrpC channels, and only T. vaginalis had a homologue of TrpV channels. In contrast, S. mansoni was found to contain TrpA and TrpC channel homologues ( Table 2 ). The presence of TrpP homologues was discussed earlier, in the context of intracellular Trp channels. The Trp channel homologues identified are consistent with a recent report of Trp channels in parasites [19], with additional homologues found to exist in S. mansoni (XP_002576118) and T. vaginalis (XP_001296819) in the current study ( Table 2 ).

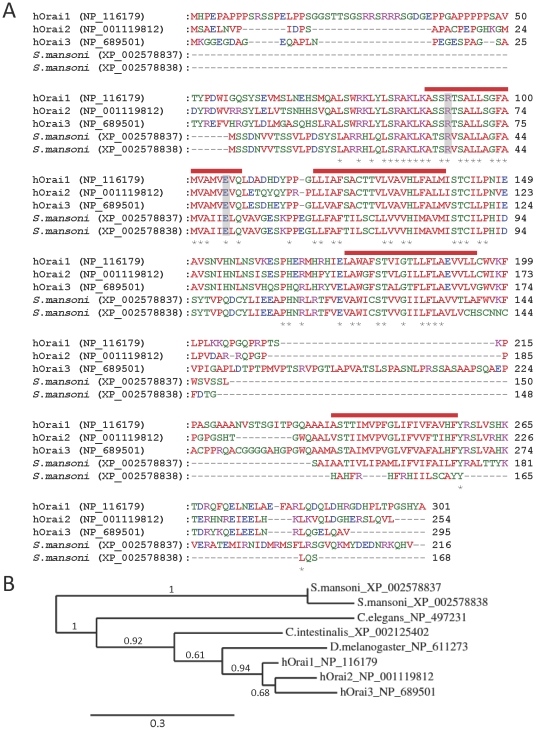

Orai and STIM homologues

Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is an almost ubiquitous feature of mammalian cells, where plasma membrane channels composed of Orai subunits mediate Ca2+ influx in response to emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores [34]-[37]. STIM subunits act as the sensors of ER Ca2+ depletion and are necessary for activation of Orai channels [38]–[40]. However, apart from a single study suggesting the presence of SOCE in Plasmodium falciparum [41], the existence of SOCE in parasites is largely unexplored, and whether Orai and STIM homologues exist in parasites is not known.

Parasite genomes were searched for homologues of these proteins, using full-length sequences of human Orai1 and STIM1 proteins. All pathogenic apicomplexan parasites examined were found to lack both Orai and STIM homologues. In contrast, the S. mansoni genome contains a gene encoding an Orai1 homologue (XP_002578837), with an alternatively spliced variant (XP_002578838) ( Figures 5A and 5B ), and a homologue of STIM1 (XP_002581211). The Orai homologue shows pronounced identity with human isoforms in the pore region ( Figure 5A ), including residues R91 and E106 of human Orai1, which are critical for pore function [34], [42], [43]. The occurrence of both Orai and STIM homologues in S. mansoni strongly suggests that a SOCE process similar to that found in mammalian cells exists in this parasite.

Figure 5. Comparison of human and S. mansoni Orai homologues.

(A) Alignments of human Orai subunits with predicted homologues from S. mansoni are shown (XP_002578838 is a shorter alternatively spliced variant of XP_002578837). Residues within the putative pore that are crucial for hOrai1 function (R91 and E106) are highlighted by grey bars. Predicted transmembrane regions of hOrai1 are indicated by red bars above the alignment, and asterisks below the alignment denote sequence identity amongst all isoforms. (B) Phylogram showing the relationship between human and S. mansoni Orai homologues as well as those of the model invertebrates C. elegans, D. melanogaster and C. intestinalis (see Methods: based on 141 high confidence positions from a multiple sequence alignment; gamma shape parameter 1.541; proportion of invariant sites 0.156). Branch length scale bar and branch support values are shown.

Cav channels

Many subytpes of plasma membrane Cav channel exist that are crucial for voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx in a wide variety of mammalian cells [14]. Human Cav channel sequences and the sequence of the Cch1 Cav channel homologue from S. cerevisiae [44], [45] were used to search for homologues in parasites. S. mansoni was found to possess genes encoding several Cav channel homologues. In addition to the previously described and cloned Cav1, Cav2A and Cav2B channels [18], we identified two novel putative Ca2+ channels (XP_002578175 and XP_002575006) ( Table 2 ). A partial sequence of another potentially novel Cav homologue was also identified (XP_002571932), which shows pronounced (but not perfect) similarity with Cav2B, but insufficient sequence was available to conclusively categorize this protein. Cav channel homologues were also found in all other parasites examined except Plasmodium spp., Cryptosporidium spp., T. vaginalis, G. intestinalis and E. histolytica ( Table 2 and Figure 6 ). We also searched parasite genomes for homologues of the CatSper channels (relatives of Cav, TPC and Trp channels) that are responsible for Ca2+ entry into mammalian spermatozoa [46]. All CatSper homologues found were identical to the Cav homologues identified above. Some of the Cav channel homologues identified in parasites are predicted to possess 18–24 transmembrane domains ( Table 2 ), consistent with a four-domain structure formed from a single subunit, similar to the organization of mammalian Cav channels ( Figure 6A ) [14]. In contrast, some of the parasite Cav channel homologues, such as those found in T. gondii and B. bovis, possess only 2–6 predicted transmembrane domains ( Table 2 ), suggesting that these may be a novel class of Cav channel homologue, formed by tetramerization of four individual subunits. Like mammalian Cav channels and Cch1, most parasite Cav channel homologues have acidic residues within their putative pore loops ( Figure 6B ). In mammalian Cav channels these residues form a negatively charged ring in the intact tetrameric channel, which facilitates selectivity for Ca2+ [14]. Fewer acidic residues are present at the analogous positions in some homologues from Leishmania spp. and Trypanosoma spp., although several acidic residues are present at other positions within the putative pore loops of these proteins ( Figure 6B ). Voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels are thought to have evolved from Cav channels and share a high degree of sequence similarity with them [47]. It is possible therefore that some of the Cav homologues identified here may be selective for Na+ rather than Ca2+ (or they may be non-selective), although experimental testing will be required to determine this. However, all parasite homologues identified lacked the characteristic DEKA selectivity filter motif of mammalian Nav channels, which is necessary for Na+ selectivity [48] ( Figure 6B ). Many of the parasite Cav channel homologues possess several regularly spaced basic residues in the TMD4 region of each domain ( Figure 7A and 7B ), suggesting functional equivalence of these regions to the voltage sensors of mammalian Cav channels [14].

Figure 6. Parasite Cav channel homologues show similarity to human Cav channels in the pore region.

(A) Schematic showing the four-domain structure of human Cav channels, with the pore loop of each domain shown in red. Cylinders indicate TMDs, and plus signs indicate the charged voltage sensor regions. (B) Multiple sequence alignments of the pore domains of human Cav channels with parasite Cav channel homologues. Only those parasite homologues containing four putative domains are shown. Sequences of human Cav1.2 (L-type), Cav2.1 (P/Q-type), Cav2.2 (N-type) and Cav3.2 (T-type) channels, as well as the S. cerevisiae Cch1 Ca2+ channel (ScCch1), are shown. L. braz denotes L. braziliensis. Selected human Nav isoforms are included, to allow comparison with the related Cav channels. The locations of acidic residues (underlined) forming an acidic ring motif in human Cav1.2 channels are indicated by asterisks. The overall motif formed by all four domains at this locus is indicated to the right of the Domain IV alignment for each channel homologue.

Figure 7. Parasite Cav channel homologues show similarity to human Cav channels in the voltage sensor region.

(A) Schematic showing the four-domain structure of human Cav channels, with the voltage sensors of each domain shown in red. (B) Multiple sequence alignments of the voltage sensor domains of human Cav channels with parasite Cav channel homologues. Only those parasite homologues containing four putative domains are shown. Asterisks indicate the position of basic residues which form the voltage sensor in each domain of human Cav1.2 channels.

Other Ca2+-permeable channels

Given the relative sparsity of Ca2+ channel homologues in the protozoan parasites studied, we also searched their genomes for genes encoding homologues of other mammalian Ca2+-permeable channels. Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) cation channels can mediate Ca2+ influx in mammalian cells [49]. We searched parasite genomes for CNG homologues, using the full-length and transmembrane region-only (to remove common cyclic nucleotide-binding domains) sequences of human CNGA1 and CNGA2. Only hits containing multiple transmembrane domains and which showed similarity in the pore and ligand-binding regions were acknowledged. No homologues were found in any of the protozoan parasites examined, except for several homologues in T. vaginalis which all contain the pore motif GYGD reminiscent of potassium channels [50]. This suggests that they may be K+-selective channels rather than Ca2+ channels, although this requires experimental testing.

We also searched protozoan genomes for genes encoding homologues of potentially Ca2+-permeable mammalian NMDA receptors, kainate receptors, AMPA receptors, pannexins, P2X4 purinergic receptors and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. No convincing homologues (ie. showing multiple transmembrane domains, pore homology, and reciprocal BLAST output) of these channels were found in any of the protozoan parasite genomes examined. In contrast to protozoan parasites, S. mansoni is known to have homologues of some of these receptors, such as nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [51], [52] and P2X receptors [53], but analysis of these likely non-selective cation channel homologues in this organism was not extended further.

Discussion

Ca2+ channels are critical for many of the most fundamental cellular processes and pharmacological modulation of these channels can lead to marked changes in cell growth and viability. These channels therefore represent attractive drug targets for treatment of infectious disease. Complex Ca2+ signalling processes exist in parasites and Ca2+-handling machinery including Ca2+-ATPases is present in these organisms [2], [3]. We have shown that genes encoding proteins homologous to mammalian intracellular Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ influx channels are present in many of the most clinically relevant pathogenic parasites ( Table 2 ). Many of these putative channels are not yet annotated in available pathogen databases, such as ToxoDB and TriTrypDB (http://eupathdb.org/eupathdb) [54]. The presence of these Ca2+ channel homologues, along with the occurrence of physiological Ca2+ signals in parasites, suggests that they participate in Ca2+ signalling within these cells. Our analysis has attempted to distinguish intracellular from plasma membrane Ca2+ channels because the distribution of Ca2+ channels profoundly affects their regulation, the amount of Ca2+ to which they have access, and the subcellular organization of the Ca2+ signals they evoke [55]. It is however increasingly clear that many Ca2+ channels can function effectively in both intracellular organelles and the plasma membrane [55]. Some parasites, whose extracellular surface may, at different stages of their lifecycle, be exposed to typical extracellular Ca2+ concentrations or to the 10,000-fold lower Ca2+ concentration of their host cell's cytosol, may perhaps exploit this plasticity in targeting of Ca2+ channels even more extensively than mammalian cells. Despite the difficulty of unambiguously assigning Ca2+ channel homologues to specific membrane compartments on the basis of their primary sequence alone, subsequent sections consider the parasite homologues by reference to the distribution of their mammalian counterparts.

Parasite intracellular Ca2+ channels

Pathogenic parasites contain a variety of intracellular Ca2+ stores including ER, mitochondria, glycosomes and acidocalcisomes, and biochemical signalling pathways analogous to those of mammalian cells have been shown to exist in parasites. Evidence exists for the presence of phospholipase C signalling pathways in parasites [56]–[58], which may sustain IP3-based effects on IP3R homologues. The intracellular messenger cADPR that activates mammalian RyRs has also been shown to be involved in parasite signalling pathways [59]–[60]. Which of these pathways might regulate the IP3R/RyR homologues shown in this study to exist in Leishmania, Trypanosoma and S. mansoni parasites remains to be tested. However, previous observations indicate that IP3 lacks Ca2+-releasing activity in Trypanosoma parasites [61]–[62]. In addition, parasite IP3R/RyR homologues, like mammalian RyRs, lack many of the basic residues required for high-affinity binding of IP3 in mouse IP3R1 [23]. These observations suggest that the IP3R/RyR homologues in these organisms might respond to a different intracellular messenger (such as cADPR), or that they might require specific conditions for activity in response to IP3.

Apicomplexan parasite genomes appeared to lack IP3R/RyR homologues, as reported by others [63]. Despite the absence of IP3R/RyR homologues in these parasites, IP3 has been reported to elicit Ca2+ release from intracellular stores of Plasmodium chabaudi [64] and E. histolytica [65], and Ca2+ release has been attributed to IP3R/RyR-like channels in T. gondii [66] and Plasmodium berghei [67]. These observations suggest that another type of IP3-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ channel exists in apicomplexan parasites. A similar situation is seen in S. cerevisiae, which lacks IP3R/RyR homologues, but has been reported to show IP3-induced Ca2+ release from vacuolar vesicles [68]. The Yvc1p (TrpY1) channel is responsible for mediating Ca2+ release from vacuolar stores of S. cerevisiae [30]–[31] and this channel is sensitive to PI(3,5)P2 [29], although whether this channel is also sensitive to IP3 is not yet known. Our searches found no homologues of Yvc1p among the genomes of pathogenic apicomplexa. However, we did identify apicomplexan homologues of the PI(3,5)P2-sensitive mammalian endolysosomal TrpML1 channel [29]. Whether mammalian TrpML channels are sensitive to IP3 has not been tested, so whether these homologues might mediate the IP3-sensitive Ca2+ release in apicomplexan parasites remains uncertain. The molecular determinants of IP3-evoked Ca2+ release in apicomplexan parasites therefore remain to be determined. The Trp, TPC, Cch1 and Cav channel homologues identified in this study (see below and Table 2 ) are also potential candidates for the role of novel IP3-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ channels in the pathogenic parasites that lack IP3R/RyR homologues.

Trp channels in mammalian cells can mediate Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in response to a wide variety of stimuli [10], [11]. In addition, the Trp channel homologue Yvc1p is the dominant Ca2+ release channel in S. cerevisiae [30], [31]. Trp channel homologues are therefore likely candidates for mediating intracellular Ca2+ release in parasites, consistent with previous identification of TrpML genes in L. major [69] and a recent report published during the course of this study which noted the presence of Trp channel homologues in a variety of parasites [19]. We identified a striking abundance of Trp channel homologues in parasites ( Table 2 ), including many TrpML homologues, which in mammalian cells have been shown to play roles in signal transduction, ion homeostasis and membrane trafficking [29], [70]. TrpP homologues are also apparent in many parasites ( Table 2 ). In mammalian cells these channels can mediate release of Ca2+ from ER stores and can be modulated by cytosolic Ca2+ via an EF-hand domain [10], [71], [72]. Whether these parasite Trp channels play similarly diverse roles in Ca2+ release, signal transduction and membrane trafficking remains an exciting avenue for future research.

The parasite acidocalcisome is similar in several ways to mammalian lysosomes from which TPCs [8], [9], TrpM [73] and TrpML [29], [70] channels mediate Ca2+ release in mammalian cells. Both organelles have a low luminal pH, high Ca2+ content and enzymatic activity [74]. TPCs in mammals and sea-urchins are regulated by intracellular NAADP [8], [9], plant TPCs may be regulated by Ca2+ [75], TrpML channels are modulated by PI(3,5)P2 [29] and TrpM2 channels are modulated primarily by adenosine diphosphoribose (ADPR), as well as cADPR and Ca2+ [73]. However, no second messenger has yet been shown to cause release of Ca2+ from acidocalcisomes [74]; neither NAADP nor IP3 releases Ca2+ from acidocalcisomes of sea urchin eggs [76]; and the effect of NAADP and ADPR on Ca2+ dynamics in parasites has not been studied. Interestingly, three of the TrpM homologues in S. mansoni (XP_002573069, XP_002571459 and XP_002578454) contain Nudix hydrolase domains, suggesting that they might be involved in signalling pathways utilizing nucleoside diphosphate derivatives such as ADPR or cADPR, as is the case with mammalian TrpM channels [77], [78]. Some TrpML homologues in kinetoplastid parasites contain a cluster of basic residues before their TMD1 regions. A similar cluster allows binding of PI(3,5)P2 to mammalian TrpML channels and subsequent channel activation [29], suggesting that the parasite homologues may also form phosphoinositide-sensitive channels. Whether the parasite homologues of mammalian TPCs or other intracellular Ca2+ channels identified in this study release Ca2+ from acidocalcisomes or other organelles in response to NAADP, ADPR, cADPR, PI(3,5)P2, IP3, Ca2+, or other intracellular messengers therefore remains to be determined.

Parasite Ca2+ influx channels

Ca2+ influx mediates physiological signalling pathways in parasites [79]–[84] and allows refilling of intracellular Ca2+ stores following intracellular Ca2+ release. The importance of Ca2+ influx pathways for cell survival in general has been demonstrated in S. cerevisiae, where lack of the plasma membrane Cch1 Ca2+ channel impairs high-affinity Ca2+ uptake, and leads to cell death in conditions of low Ca2+ concentration or when Ca2+ influx is required [44], [45]. Recently it has likewise been shown that in Leishmania parasites, Ca2+ influx is necessary for thermotolerance [84]. Many protozoan parasites exist within mammalian cells for part of their life cycle, where Ca2+ levels are maintained at low levels (typically <100 nM). These parasites therefore seem likely to require unique strategies in order to enhance Ca2+ uptake. Residence of some parasites within parasitophorous vacuoles or other membraneous compartments [16], [85] helps to circumvent this problem by surrounding the parasite with elevated Ca2+, but parasite plasma membrane Ca2+ channels or transporters with novel properties may also be essential, especially for those parasites directly exposed to the cytosol, such as T. cruzi [16], [86]. The Ca2+ channel homologues described in this study may differentially contribute to Ca2+ influx during different phases of parasite life cycles and may have novel properties that allow their function in ionic conditions that differ substantially from those experienced by their mammalian counterparts.

Cav channel homologues were found in many of the pathogenic parasites examined, suggesting that these proteins have a widespread function in parasites. The presence in these homologues of charged regions analogous to the voltage sensors of Cav channels suggests that they might be gated by transmembrane voltage, although this remains to be tested experimentally. Homologues of mammalian Ca2+-permeable TrpA, TrpC and TrpV subtypes capable of mediating plasma membrane Ca2+ influx were absent from most protozoan parasites. In contrast, TrpA and TrpC channel homologues were found in S. mansoni, although their exact subtype categorization was unclear. Since in addition to mediating intracellular Ca2+ release, TrpP channels are also capable of mediating Ca2+ influx in mammalian cells when located in the plasma membrane [33], [87], the “intracellular” Trp channel homologues identified in this study may also contribute to Ca2+ influx in parasites. Mammalian Trp channels are modulated by diverse stimuli [10], [11], [32] making them interesting candidates for the transduction of environmental stimuli into physiological responses in S. mansoni.

Homologues of the Orai channels which mediate SOCE in mammalian cells [34]–[37], were found to be absent from all pathogenic protozoa examined. In addition, the ER Ca2+-sensing STIM proteins responsible for activation of Orai proteins [38]–[40] were also absent from these parasites. This suggests that either these parasites lack SOCE, or that other proteins might fulfil the roles of both the pore-forming and Ca2+-sensing subunits of SOCE channels in these organisms. In mammalian cells, TrpC channels have also been shown to contribute to SOCE in a variety of cells [88], suggesting the possibility that Trp channel homologues ( Table 2 ) might fulfil roles as SOCE channels in some of these protozoa. Interestingly, in contrast to the absence of Orai/STIM proteins in the protozoan parasites tested, S. mansoni has an alternatively spliced Orai1 homologue and a STIM1 homologue, suggesting that Orai/STIM-mediated SOCE exists in this parasite.

The expression and function of the putative Ca2+ channel homologues identified in this study will in future need to be measured experimentally in order to confirm their status as Ca2+ channels. Homologues of other mammalian non-selective cation channels may also be found in parasites and may contribute to Ca2+ signalling pathways in these organisms. In addition, some of the Ca2+ channel homologues identified in this study may play roles in flux of other ions such as Na+ or K+, perhaps in a lifecycle-dependent manner, given the substantial changes in ionic composition of the extracellular environment during different stages of the lifecycle in many parasites.

Ca2+ channel homologues in parasites and their free-living relatives

Comparison of the genomes of the parasitic Apicomplexa examined here (Plasmodium spp., T. gondii and Cryptosporidium spp.) with their free-living ciliate relative Paramecium reveals differences in the complement of genes encoding Ca2+ channels. IP3R/RyR homologues are absent in the Apicomplexa examined, whereas they are present in Paramecium [89]. Likewise, Cav channels with a four-domain architecture similar to mammalian Cav channels are absent in the Apicomplexa (T. gondii has several more distantly related homologues, but these do not have a four-domain structure), whereas they are present in Paramecium (data not shown). Whether the apparent absence of IP3R/RyR and Cav channels in Apicomplexa occurred as a result of the acquisition of a parasitic existence is unclear. In contrast, both the Apicomplexa examined here and Paramecium (data not shown) appear to have Trp channel homologues. Paramecium [90] and the apicomplexan parasite P. falciparum [41] have been reported to display SOCE, although the molecular basis is unknown. As with the Apicomplexa, our searches did not reveal any genes encoding convincing homologues of Orai1 in Paramecium (data not shown), suggesting that lack of Orai homologues in Apicomplexa may not be a result of transition to parasitism. The channel-forming proteins underlying SOCE in these organisms remain to be identified.

A comparison of the flagellate parasites examined here (Trypanosoma spp. and Leishmania spp.) with their free-living choanoflagellate relative Monosiga brevicollis also reveals differences. Both M. brevicollis [91] and the kinetoplastid parasites examined here have homologues of IP3Rs, Cav and Trp channels, although M. brevicollis has a greater diversity of these channels [91]. However, while Orai and STIM homologues are present in M. brevicollis [91], they appear to be absent in the kinetoplastid parasites. Again, whether these differences arose due to the transition from a free-living to a parasitic existence is unclear.

Relevance of parasite Ca2+ channels to therapy

A role for Ca2+ in the action of some anti-parasitic drugs has long been appreciated [92] and many anti-parasitic drugs that are known to affect mammalian Ca2+ channels have effects on Ca2+ signalling in parasites. For example, amiodarone [93], nimodipine [94] and several other 1,4-dihydropyridines [95], as well as a range of Ca2+ channel and calmodulin antagonists [96] may exert anti-parasitic effects via disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis in parasites. Anti-parasitic actions of other agents such as antimicrobial peptides [97], parasite-specific antibodies [98] and curcumin [99] also affect Ca2+ homeostasis in parasites. In addition, the widely used antimalarial artemisinin may affect Ca2+ homeostasis via inhibition of parasite sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) [100], although this has recently been contested [101], [102] and other mechanisms for its action have been hypothesized [103]. Praziquantel [104], [105], chloroquine [106], [107], dantrolene [59], [108], and suramin [109], [110] are also currently used anti-parasitic drugs with complex and unclear mechanisms of action, that may involve modulation of Ca2+ signalling. We speculate that in addition to affecting their currently known targets, such as the plasmodial surface anion channel in the case of dantrolene [111] and Cavβ subunits in the case of praziquantel [112], these drugs may also alter the activity of the parasite Ca2+ channel homologues described in this study and hence perturb Ca2+ signalling pathways involved in parasite survival. In particular, we suggest that suramin, a known RyR agonist [113], [114] and dantrolene, a known RyR antagonist [115], [116], may affect the RyR/IP3R homologues shown in this study to exist in Trypanosoma, Leishmania and S. mansoni parasites. This represents a potentially novel mechanism of action for these clinically useful drugs.

The apparent scarcity of Ca2+ channels in parasites relative to the wide array of isoforms in mammalian cells suggests that Ca2+ signalling in parasites may rely on a less redundant repertoire of Ca2+ channels. This characteristic may increase the susceptibility of parasites to drugs that target these channels.

Although parasite Ca2+ channel homologues show significant similarity to their mammalian counterparts, sequence differences in functionally and pharmacologically important domains (eg. the ion-conducting pore region) exist, such as those shown to exist between human and parasite IP3R/RyR homologues ( Figure 1 ). As pharmacological blockers of IP3Rs and RyRs such as xestospongin-C and ryanodine are thought to bind within the pore region [24], [25], [117], this sequence divergence suggests the possibility of developing drugs with specificity for parasite homologues. Experimental observations also suggest the possibility for drug selectivity. For example, S. mansoni muscle fibres show RyR-like Ca2+ responses that are activated by caffeine but insensitive to the classical RyR blockers, ruthenium red and neomycin [118]. Drugs with selectivity for insect RyRs have been described and these have been utilized to develop novel insecticides, which do not affect mammalian RyRs [119]. A variety of 1,4-dihydropyridines have also been shown to exhibit some selectivity for parasite Ca2+ influx channels over mammalian counterparts, and molecular determinants for their specificity have been defined [95]. These results suggest that rational design of therapeutic strategies targeted against parasite Ca2+ channels may be an attractive prospect and that newly discovered insecticidal RyR modulators, 1,4-dihydropyridines, or other Ca2+-permeable channel agonists and antagonists may represent attractive lead compounds.

This study presents the opportunity for cloning and functional characterization of putative intracellular Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ influx channels in pathogenic parasites, as well as the development of novel therapeutics. Future studies of parasite signalling pathways and completion of further parasite genome sequencing projects will lead to a deeper understanding of the presence and function of these channels in pathogenic parasites.

Materials and Methods

Genomes analyzed

The genomes of the following pathogenic parasites were examined (annotation release date in parentheses): Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 (May 2007), Plasmodium vivax SaI-1 (Jan 2008), Plasmodium knowlesi strain H (Apr 2008), Toxoplasma gondii ME49 (May 2008), Babesia bovis T2Bo (Mar 2008), Cryptosporidium hominis TU502 (Mar 2008), Cryptosporidium muris RN66 (Oct 2008), Cryptosporidium parvum Iowa II (Nov 2006), Leishmania braziliensis MHOM/BR/75/M2904 (Oct 2007), Leishmania infantum JPCM5 (May 2007), Leishmania major Friedlin (Mar 2008), Trypanosoma brucei TREU927 (Dec 2006), Trypanosoma cruzi CL Brener (Dec 2007), Entamoeba histolytica HM-1:IMSS (Jun 2010), Giardia intestinalis (Mar 2008), Trichomonas vaginalis G3 (Mar 2008), and Schistosoma mansoni (Jul 2011). No homologues of any Ca2+ channels examined were identified in the genomes of E. histolytica or G. intestinalis. Other genomes analyzed include those of: Homo sapiens (Dec 2010), Caenorhabditis elegans (Apr 2011), Drosophila melanogaster (May 2011), Paramecium tetraurelia (Mar 2008) and Ciona intestinalis (Sept 2008).

BLAST searches, alignments and topology analysis

BLASTP analysis was carried out in all cases, using the following human sequences (GenBank accession number in parentheses): full-length or pore sequences of IP3R1 (Q14643.2; pore region amino acids 2536-2608) or RyR1 (P21817.3; pore region residues 4877-4948), and full-length human sequences of TrpA1 (NP_015628; N-truncated sequence residues 765-end), TrpV1 (NP_061197; N-truncated sequence residues 430-end), TrpC1 (P48995; N-truncated sequence residues 350-end), CNGA1 (EAW93049; transmembrane sequence residues 200-420), CNGB1 (NP_001288), NMDA receptor NR1 (Q05586), NMDA receptor N2 (Q12879), AMPA receptor GRIA1 (P42261.2), kainate receptor GRIK1 (P39086), nAChR-alpha1 (ABR09427), purinergic receptor P2X4 (NP_002551.2), pannexin-1 (AAH16931), Orai1 (NP_116179.2), STIM1 (AAH21300), TPC1 (NP_001137291.1), TPC2 (NP_620714.2), TrpP1 (NP_001009944), TrpP2 (NP_000288), TrpM1 (NP_002411), TrpML1 (NP_065394), CatSper1 (Q8NEC5.3), mitochondrial uniporter (NP_612366.1) and Cav1.2 (NP_955630.2). Sequences of the S. cerevisiae Ca2+ channel subunit Cch1 (CAA97244) and Arabidopsis thaliana TPC1 (AAK39554) were also used to search for parasite homologues.

BLASTP searches of the genomes of protozoan parasites, H. sapiens, C. elegans, D. melanogaster and C. intestinalis were carried out against the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) genomic protein databases. Searches of the P. tetraurelia genome were carried out using the BLASTP facility of ParameciumDB (v.1.59) (http://paramecium.cgm.cnrs-gif.fr) [120] to search the protein database (version 1, published 2006). The S. mansoni genome was searched using the BLASTP search facility of GeneDB (http://www.genedb.org/blast/submitblast/GeneDB_Smansoni) and S. mansoni BLASTP server twinscan2 peptide prediction facility (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/blast/submitblast/s_mansoni) hosted by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK [121]. Hits identified were then used as bait in further BLASTP searches (non-redundant protein database at NCBI) to identify corresponding annotated proteins. Several procedures ensured that hits were likely channel homologues. Firstly, the presence of multiple transmembrane domains was confirmed using TOPCONS [122]. Secondly, reciprocal BLASTP searches (non-redundant protein database at NCBI) were made, using the identified parasite hits as bait, and only proteins that gave the original mammalian protein family as hits were analyzed further. Thirdly, the presence of conserved domains was confirmed using the Conserved Domains Database (NCBI). Lastly, where possible pore homology was confirmed by sequence alignment using ClustalW2 (European Bioinformatics Institute). Where hits showed homology to more than one mammalian channel, BLASTP analysis against human sequences was used to identify the channel with greatest sequence similarity. Multiple sequence alignments were made using ClustalW2.1 and physiochemical residue colours are shown. For phylogenetic analysis, multiple sequence alignments were made with MUSCLE v3.7 (or ClustalW2.1 in the case of the lengthy IP3R/RyR homologues) using default parameters. After using GBLOCKS at low stringency to remove regions of low confidence, and removing gaps, Maximum Likelihood analysis was carried out using PhyML v3.0 (WAG substitution model; 4 substitution rate categories; default estimated gamma distribution parameters; default estimated proportions of invariable sites; 100 bootstrapped data sets). Phylogenetic trees were depicted using TreeDyn (v198.3). MUSCLE, GBLOCKS, PhyML and TreeDyn were all functions of Phylogeny.fr (http://www.phylogeny.fr/) [123].

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was funded by a Meres Senior Research Associateship from St. John's College, Cambridge (to DLP) and by the Wellcome Trust. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Philosoph H, Zilberstein D. Regulation of intracellular calcium in promastigotes of the human protozoan parasite Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10420–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno SN, Docampo R. Calcium regulation in protozoan parasites. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:359–64. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagamune K, Moreno SN, Chini EN, Sibley LD. Calcium regulation and signaling in apicomplexan parasites. Subcell Biochem. 2008;47:70–81. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78267-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billker O, Lourido S, Sibley LD. Calcium-dependent signaling and kinases in apicomplexan parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:612–22. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks AR. Intracellular calcium-release channels: regulators of cell life and death. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H597–605. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:933–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fill M, Copello JA. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calcraft PJ, Ruas M, Pan Z, Cheng X, Arredouani A, et al. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature. 2009;459:596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature08030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brailoiu E, Churamani D, Cai X, Schrlau MG, Brailoiu GC, et al. Essential requirement for two-pore channel 1 in NAADP-mediated calcium signaling. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:201–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong XP, Wang X, Xu H. TRP channels of intracellular membranes. J Neurochem. 2010;113:313–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gees M, Colsoul B, Nilius B. The role of transient receptor potential cation channels in Ca2+ signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003962. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Docampo R, Moreno SN. The acidocalcisome. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;114:151–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Raychaudhury B, Banerjee S, Das B, Datta SC. An intracellular calcium store is present in Leishmania donovani glycosomes. Exp Parasitol. 2006;113:161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Jones BF, Mercer JC, Trebak M, et al. Emerging perspectives in store-operated Ca2+ entry: roles of Orai, Stim and TRP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1147–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sibley LD. Invasion and intracellular survival by protozoan parasites. Immunol Rev. 2011;240:72–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg RM. Ca2+ signalling, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and praziquantel in flatworm neuromusculature. Parasitology. 2005;131(Suppl):S97–108. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohn AB, Lea J, Roberts-Misterly JM, Anderson PA, Greenberg RM. Structure of three high voltage-activated calcium channel alpha1 subunits from Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitology. 2001;123:489–97. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001008691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolstenholme AJ, Williamson SM, Reaves BJ. TRP channels in parasites. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:359–71. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foskett JK, White C, Cheung KH, Mak DO. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:593–658. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponting CP. Novel repeats in ryanodine and IP3 receptors and protein O-mannosyltransferases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:48–50. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosanac I, Yamazaki H, Matsu-Ura T, Michikawa T, Mikoshiba K, et al. Crystal structure of the ligand binding suppressor domain of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Mol Cell. 2005;17:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshikawa F, Morita M, Monkawa T, Michikawa T, Furuichi T, et al. Mutational analysis of the ligand binding site of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18277–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen SR, Li P, Zhao M, Li X, Zhang L. Role of the proposed pore-forming segment of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) in ryanodine interaction. Biophys J. 2002;82:2436–47. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75587-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranatunga KM, Moreno-King TM, Tanna B, Wang R, Chen SR, et al. The Gln4863Ala mutation within a putative, pore-lining trans-membrane helix of the cardiac ryanodine receptor channel alters both the kinetics of ryanoid interaction and the subsequent fractional conductance. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:840–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishibashi K, Suzuki M, Imai M. Molecular cloning of a novel form (two-repeat) protein related to voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:370–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furuichi T, Cunningham KW, Muto S. A putative two pore channel AtTPC1 mediates Ca2+ flux in Arabidopsis leaf cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:900–5. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montell C. The TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE 2005. 2005:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong XP, Shen D, Wang X, Dawson T, Li X, et al. PI(3,5)P2 controls membrane traffic by direct activation of mucolipin Ca2+ release channels in the endolysosome. Nat Commun. 2010;1:38. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer CP, Zhou XL, Lin J, Loukin SH, Kung C, et al. A TRP homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae forms an intracellular Ca2+-permeable channel in the yeast vacuolar membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7801–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141036198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denis V, Cyert MS. Internal Ca2+ release in yeast is triggered by hypertonic shock and mediated by a TRP channel homologue. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:29–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salido GM, Sage SO, Rosado JA. TRPC channels and store-operated Ca2+ entry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsiokas L. Function and regulation of TRPP2 at the plasma membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90277.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–85. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, et al. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312:1220–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeromin AV, Zhang SL, Jiang W, Yu Y, Safrina O, et al. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prakriya M, Feske S, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Rao A, et al. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–3. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, et al. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, et al. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. 2005;437:902–5. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beraldo FH, Mikoshiba K, Garcia CR. Human malarial parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, displays capacitative calcium entry: 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate blocks the signal transduction pathway of melatonin action on the P. falciparum cell cycle. J Pineal Res. 2007;43:360–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamashita M, Navarro-Borelly L, McNally BA, Prakriya M. Orai1 mutations alter ion permeation and Ca2+-dependent fast inactivation of CRAC channels: evidence for coupling of permeation and gating. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:525–40. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y, Ramachandran S, Oh-Hora M, Rao A, Hogan PG. Pore architecture of the ORAI1 store-operated calcium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4896–901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001169107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paidhungat M, Garrett S. A homolog of mammalian, voltage-gated calcium channels mediates yeast pheromone-stimulated Ca2+ uptake and exacerbates the cdc1(Ts) growth defect. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6339–47. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer M, Schnell N, Chattaway J, Davies P, Dixon G, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae CCH1 gene is involved in calcium influx and mating. FEBS Lett. 1997;419:259–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren D, Navarro B, Perez G, Jackson AC, Hsu S, et al. A sperm ion channel required for sperm motility and male fertility. Nature. 2001;413:603–9. doi: 10.1038/35098027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu FH, Catterall WA. The VGL-chanome: a protein superfamily specialized for electrical signaling and ionic homeostasis. Sci STKE 2004. 2004:re15. doi: 10.1126/stke.2532004re15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Favre I, Moczydlowski E, Schild L. On the structural basis for ionic selectivity among Na+, K+, and Ca2+ in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biophys J. 1996;71:3110–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79505-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biel M, Zong X, Hofmann F. Cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels molecular diversity, structure, and cellular functions. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1996;6:274–80. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(96)00105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heginbotham L, Lu Z, Abramson T, MacKinnon R. Mutations in the K+ channel signature sequence. Biophys J. 1994;66:1061–7. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bentley GN, Jones AK, Oliveros Parra WG, Agnew A. ShAR1alpha and ShAR1beta: novel putative nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from the platyhelminth blood fluke Schistosoma. Gene. 2004;329:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bentley GN, Jones AK, Agnew A. ShAR2beta, a divergent nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit from the blood fluke Schistosoma. Parasitology. 2007;134:833–40. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006002162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agboh KC, Webb TE, Evans RJ, Ennion SJ. Functional characterization of a P2X receptor from Schistosoma mansoni. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41650–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aurrecoechea C, Heiges M, Wang H, Wang Z, Fischer S, et al. ApiDB: integrated resources for the apicomplexan bioinformatics resource center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D427–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor CW, Prole DL, Rahman T. Ca2+ channels on the move. Biochemistry. 2009;48:12062–80. doi: 10.1021/bi901739t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furuya T, Kashuba C, Docampo R, Moreno SN. A novel phosphatidylinositol-phospholipase C of Trypanosoma cruzi that is lipid modified and activated during trypomastigote to amastigote differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6428–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fang J, Marchesini N, Moreno SN. A Toxoplasma gondii phosphoinositide phospholipase C (TgPI-PLC) with high affinity for phosphatidylinositol. Biochem J. 2006;394:417–25. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Paulo Martins V, Okura M, Maric D, Engman DM, Vieira M, et al. Acylation-dependent export of Trypanosoma cruzi phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C to the outer surface of amastigotes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30906–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chini EN, Nagamune K, Wetzel DM, Sibley LD. Evidence that the cADPR signalling pathway controls calcium-mediated microneme secretion in Toxoplasma gondii. Biochem J. 2005;389:269–77. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones ML, Cottingham C, Rayner JC. Effects of calcium signaling on Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion and post-translational modification of gliding-associated protein 45 (PfGAP45). Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;168:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moreno SN, Vercesi AE, Pignataro OP, Docampo R. Calcium homeostasis in Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes: presence of inositol phosphates and lack of an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive calcium pool. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;52:251–61. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90057-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Docampo R, Moreno SN, Vercesi AE. Effect of thapsigargin on calcium homeostasis in Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes and epimastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;59:305–13. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90228-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagamune K, Moreno SN, Chini EN, Sibley LD. Calcium regulation and signaling in apicomplexan parasites. Subcell Biochem. 2008;47:70–81. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78267-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Passos AP, Garcia CR. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate induced Ca2+ release from chloroquine-sensitive and -insensitive intracellular stores in the intraerythrocytic stage of the malaria parasite P. chabaudi. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:155–60. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raha S, Dalal B, Biswas S, Biswas BB. Myo-inositol trisphosphate-mediated calcium release from internal stores of Entamoeba histolytica. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lovett JL, Marchesini N, Moreno SN, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma gondii microneme secretion involves intracellular Ca2+ release from inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3)/ryanodine-sensitive stores. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25870–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raabe AC, Wengelnik K, Billker O, Vial HJ. Multiple roles for Plasmodium berghei phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C in regulating gametocyte activation and differentiation. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:955–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Belde PJ, Vossen JH, Borst-Pauwels GW, Theuvenet AP. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate releases Ca2+ from vacuolar membrane vesicles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:113–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81460-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chenik M, Douagi F, Ben Achour Y, Khalef NB, Ouakad M, et al. Characterization of two different mucolipin-like genes from Leishmania major. Parasitol Res. 2005;98:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-0012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng X, Shen D, Samie M, Xu H. Mucolipins: Intracellular TRPML1-3 channels. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2013–21. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koulen P, Cai Y, Geng L, Maeda Y, Nishimura S, et al. Polycystin-2 is an intracellular calcium release channel. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:191–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Petri ET, Celic A, Kennedy SD, Ehrlich BE, Boggon TJ, et al. Structure of the EF-hand domain of polycystin-2 suggests a mechanism for Ca2+-dependent regulation of polycystin-2 channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9176–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912295107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lange I, Yamamoto S, Partida-Sanchez S, Mori Y, Fleig A, et al. TRPM2 functions as a lysosomal Ca2+-release channel in beta cells. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra23. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moreno SN, Docampo R. The role of acidocalcisomes in parasitic protists. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2009;56:208–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2009.00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peiter E, Maathuis FJ, Mills LN, Knight H, Pelloux J, et al. The vacuolar Ca2+-activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature. 2005;434:404–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramos IB, Miranda K, Pace DA, Verbist KC, Lin FY, et al. Calcium- and polyphosphate-containing acidic granules of sea urchin eggs are similar to acidocalcisomes, but are not the targets for NAADP. Biochem J. 2010;429:485–95. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perraud AL, Fleig A, Dunn CA, Bagley LA, Launay P, et al. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature. 2001;411:595–9. doi: 10.1038/35079100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kolisek M, Beck A, Fleig A, Penner R. Cyclic ADP-ribose and hydrogen peroxide synergize with ADP-ribose in the activation of TrpM2 channels. Mol Cell. 2005;18:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sarkar D, Bhaduri A. Temperature-induced rapid increase in cytoplasmic free Ca2+ in pathogenic Leishmania donovani promastigotes. FEBS Lett. 1995;375:83–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Prasad A, Kaur S, Malla N, Ganguly NK, Mahajan RC. Ca2+ signaling in the transformation of promastigotes to axenic amastigotes of Leishmania donovani. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;224:39–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1011965109446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]