Abstract

Initially identified as an inhibitor of oriC-initiated DNA replication in vitro, the ArgP or IciA protein of Escherichia coli has subsequently been described as a nucleoid-associated protein and also as a transcriptional regulator of genes involved in DNA replication (dnaA and nrdA) and amino acid metabolism (argO, dapB, and gdhA [the last in Klebsiella pneumoniae]). ArgP mediates lysine (Lys) repression of argO, dapB, and gdhA in vivo, for which two alternative mechanisms have been identified: at the dapB and gdhA regulatory regions, ArgP binding is reduced upon the addition of Lys, whereas at argO, RNA polymerase is trapped at the step of promoter clearance by Lys-bound ArgP. In this study, we have examined promoter-lac fusions in strains that were argP+ or ΔargP or that were carrying dominant argP mutations in order to identify several new genes that are ArgP-regulated in vivo, including lysP, lysC, lysA, dapD, and asd (in addition to argO, dapB, and gdhA). All were repressed upon Lys supplementation, and in vitro studies demonstrated that ArgP binds to the corresponding regulatory regions in a Lys-sensitive manner (with the exception of argO, whose binding to ArgP was Lys insensitive). Neither dnaA nor nrdA was ArgP regulated in vivo, although their regulatory regions exhibited low-affinity binding to ArgP. Our results suggest that ArgP is a transcriptional regulator for Lys repression of genes in E. coli but that it is noncanonical in that it also exhibits low-affinity binding, without apparent direct regulatory effect, to a number of additional sites in the genome.

INTRODUCTION

The functional role of the ArgP or IciA protein in Escherichia coli is an enigma in that it has been variously described as a canonical transcriptional activator, an inhibitor of chromosome replication initiation, and a nucleoid-associated protein. First identified as a protein that binds specific sequences in oriC in vitro to inhibit the initiation of replication (21–23, 46), ArgP was shown (46) to be a member of the family of LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs) and, subsequently, to be essential both in vivo and in vitro for transcription of the gene encoding the l-arginine (Arg) exporter ArgO (26, 32); in Corynebacterium glutamicum, LysG and LysE are orthologous to E. coli ArgP and ArgO, respectively, and LysG is required for LysE transcription (5). ArgP-regulated transcription in vivo has also been demonstrated for the genes dapB of E. coli (7) and gdhA of Klebsiella pneumoniae (15). (That E. coli gdhA may be under ArgP control had also been suggested earlier [33].) In addition, in vitro studies have suggested that ArgP activates the transcription of the dnaA and nrdA genes that are involved in DNA metabolism and replication (20, 27–29).

At the same time, ArgP has also been reported as a nucleoid-associated protein that shows apparently sequence-nonspecific DNA binding activity (2). The protein exhibits affinity for AT-rich and curved DNA sequences, as determined in vitro by DNase I footprinting or electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) (2, 48). ArgP exists as a dimer at an estimated concentration of around 100 to 400 molecules per cell (that is, around 200 to 800 nM monomers) (3, 23).

As mentioned above, one of the well-characterized targets for transcriptional regulation by ArgP is the argO gene (26, 32, 37). Transcription of argO in vivo is activated both by Arg and its toxic analog l-canavanine, both effects being mediated by ArgP. On the other hand, argO transcription is drastically reduced in medium supplemented with l-lysine (Lys), to a level equivalent to that observed in ΔargP mutants; when both Arg and Lys are present, it is the Lys effect on argO which predominates. Dominant mutations in argP have been identified (designated argPd) that confer an l-canavanine-resistant phenotype and act in trans to considerably increase argO transcription in vivo over that obtained in the argP+ strain (32).

In vitro, the ArgP protein exhibits high-affinity binding to the argO regulatory region in the presence of either coeffector, Arg or Lys, as well as in their absence (7, 26, 37). Stable recruitment by ArgP of RNA polymerase to the argO promoter is observed in the presence of Arg or Lys, following which the two coeffectors exert dramatically opposite effects in the ternary complex; whereas productive transcription from the argO promoter is stimulated in the presence of ArgP and Arg, RNA polymerase is trapped at the promoter at a step after open complex formation in the presence of ArgP and Lys (26).

As with argO, in other ArgP-regulated promoters, such as dapB of E. coli and gdhA of K. pneumoniae, Lys supplementation is associated with a decrease in transcription in vivo. In these cases, however, the addition of Lys results in a decreased affinity of ArgP to bind to the corresponding regulatory regions in vitro, suggesting that it is the failure of RNA polymerase recruitment at the promoters which is responsible for Lys repression (7, 15).

In this study, we have used the ΔargP and argPd mutations to examine ArgP's role in the regulation in vivo of a number of genes in E. coli that were chosen on the basis of either their identification in the earlier reports or their roles in Lys and Arg metabolism. EMSA experiments to determine ArgP binding with the upstream regulatory regions of these genes in vitro were also undertaken. Our results indicate that negative regulation involving Lys as coeffector is mediated by ArgP and that the target genes include argO, lysP, lysC, asd, dapB, dapD, lysA, and gdhA. Of the genes listed above, argO was unique in several respects, including its responsiveness to Arg, ArgP binding even in the presence of Lys, and behavior with the argPd mutations. Other genes, such as dnaA and nrdA, did exhibit binding to ArgP in vitro (that was Lys insensitive) but were not regulated by ArgP in vivo. These findings implicate a role for ArgP in Lys metabolism and homeostasis in E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth media, bacterial strains, and plasmids.

The routine defined and rich growth media were, respectively, glucose-minimal A (with amino acids supplemented at 40 μg/ml or otherwise as indicated below) and LB medium, as described previously (31), and the growth temperature was 37°C. The proportion of acid and basic phosphate in minimal A medium was suitably adjusted (42) to obtain a growth medium of pH 5.8. Ampicillin (Amp), kanamycin (Kan), and spectinomycin (Sp) were each used at 50 μg/ml, and trimethoprim (Tp) at 30 μg/ml. l-Arabinose (Ara) supplementation was at 0.2%.

The E. coli K-12 strains used in the study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids previously described include the following (salient features are in parentheses): pBAD18 (pMB9 replicon, Ampr, for Ara-induced expression of target genes) (19), pMU575 (IncW single-copy-number replicon with promoterless lacZ gene, Tpr) (1), pCP20 (pSC101-based Ts replicon encoding Flp recombinase, Ampr) (14), and pHYD1723 (pMU575 derivative with 402-bp argO promoter fragment upstream of lacZ, Tpr) (26). Plasmids bearing argPd alleles encoding one of the ArgP variants A68V, S94L, P108S, V144M, P217L, or R295C and the corresponding argP+ (pHYD915) and vector (pCL1920) controls (pSC101 replicons, Spr) were as described in Nandineni and Gowrishankar (32).

Table 1.

List of E. coli K-12 strains

| Straina | Genotypeb |

|---|---|

| MC4100 | Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 araD139 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 |

| GJ4748 | MC4100 argR64 zhb-914::Tn10dCm |

| GJ9602 | MC4100 ΔargP |

| GJ9623 | MC4100 ΔlysP |

| GJ9624 | MC4100 ΔargP ΔlysP |

| GJ9647 | MC4100 ΔcadC::Kan |

| GJ9648 | MC4100 ΔargP ΔcadC::Kan |

| GJ9649 | MC4100 ΔlysP ΔcadC::Kan |

| GJ9650 | MC4100 araD+ |

| GJ9651 | MC4100 araD+ ΔargP |

| GJ9652 | MC4100 araD+ ΔlysR::Kan |

| GJ9653 | MC4100 araD+ ΔargP ΔlysR::Kan |

Strains described earlier (32) include MC4100 and GJ4748. All other strains were constructed in this study.

Genotype designations are as described previously (6). All strains are F−. The ΔargP, ΔlysP, ΔlysR, and ΔcadC alleles were introduced as Kanr deletion-insertion mutations from the Keio knockout collection (4), and where necessary, the Kanr marker was then excised by site-specific recombination with the aid of plasmid pCP20, as described previously (14). The latter mutations are shown without the Kanr designation in the table.

The promoter-lac fusion derivatives that were constructed using plasmid pMU575 in this study are described in Table 2. Plasmid pHYD2673 is a pBAD18 derivative carrying the lysA+ gene from E. coli (genomic coordinates 2975628 to 2976968 [40]) cloned downstream of Para of the vector; the gene was PCR amplified from genomic DNA with the primer pairs 5′-ACAAGGTACCTTTTATGATGTGGCGT-3′ and 5′-ACAATCTAGAAGTCATCATGCAACC (KpnI and XbaI sites, respectively, are italicized in the two primers), and the KpnI-XbaI-digested product was cloned into the corresponding sites of pBAD18. The construction of plasmid pHYD2606 encoding the ArgPd P274S variant is described below.

Table 2.

List of pMU575-derived promoter-lac fusion plasmids constructed in this studya

| Plasmid | Promoter [fragment size (bp)] | Primer 1 (enzyme) | Primer 2 (enzyme) | Extent (genomic coordinates)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pHYD2602 | gdhA (435) | 5′-ATTTTGATCCTGCAGAACGCAGCACTG-3′ (P) | 5′-GTTTGATTCGGATCCCGCTTTTGGACATG-3′ (B) | −322 to +113 (1840009–1840443) |

| pHYD2610 | dapD (373) | 5′-CGCCATTTTACTGCAGAAACCGAAG-3′ (P) | 5′-CGGGTAACGGATCCTGCATTGGCT-3′ (B) | −273 to +100 (185877–186249) |

| pHYD2636 | lysP (238) | 5′-GCGCTTTCTGCAGTATTGCGATCC-3′ (P) | 5′-TAGTTTCGGATCCCATACAAAAATGC-3′ (B) | −206 to +32 (2246550–2246787) |

| pHYD2647 | lysP (158) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGTTCGCCAGAAAA-3′ (P) | 5′-TAGTTTCGGATCCCATACAAAAATGC-3′ (B) | −114 to +32 (2246538–2246695) |

| pHYD2648 | lysP (120) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGCTGGGCGATCAT-3′ (P) | 5′-TAGTTTCGGATCCCATACAAAAATGC-3′ (B) | −76 to +32 (2246538–2246657) |

| pHYD2658 | artJ (416) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGCAAAGCGCTGGCA-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCGGATAGGTGGCTGAAA-3′ (B) | −270 to +146 (899703–900118) |

| pHYD2659 | artP (288) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGGAATCGCTAACGCC-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCTATCGAACAGCGCC-3′ (B) | −192 to +96 (902896–903183) |

| pHYD2660 | argT (367) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGATCTCTTTGCCCGC-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCGTAGCGCCGCATA-3′ (B) | −236 to +131 (2425740–2426106) |

| pHYD2661 | hisJ (306) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGTGTCTACGGTGACTG-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCTCGCAGCAAACG-3′ (B) | −187 to +119 (2424740–2425045) |

| pHYD2664 | lysC (615) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGGTCTGCGTTGGATT-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAATCTAGACGGTTCATGGCGT-3′ (X) | −244 to +371 (4231191–4231805) |

| pHYD2668 | asd (343) | 5′-GTATGTTTCAGTGTCGACATGAAAATAG-3′ (S) | 5′-GGCGTCGAAGCTTCGCTCTTCAACCA-3′ (H) | −207 to +136 (3572827–3573169) |

| pHYD2669 | dapB (386) | 5′-CCCTGTTTTGCTGCAGTGGAAAC-3′ (P) | 5′-AATGCCAGCGGATCCTGAATCAAC-3′ (B) | −285 to +101 (28057–28442) |

| pHYD2670 | lysA (268) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGCCTCAGTCAGGCTTC-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCCAGCCAAATTCAGC-3′ (B) | −139 to +129 (2976844–2977111) |

| pHYD2671 | dnaA (668) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGTTTCATGGCGATT-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCGCTGGTAACTCAT-3′ (B) | −460 to +208 (3881696–3882363) |

| pHYD2672 | nrdA (481) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGCGCCATCAACAAT-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCGTCGAGATTGATGC-3′ (B) | −311 to +170 (2342465–2342945) |

| pHYD2674 | cadB (527) | 5′-TTTAATTTACCTGCAGGGGCAAAC-3′ (P) | 5′-TGCAATACCGGATCCCATCATATTA-3′ (B) | −387 to +140 (4357989–4358515) |

| pHYD2675 | lysR (268) | 5′-ACAACTGCAGCAGCCAAATTCAGC-3′ (P) | 5′-ACAAGGATCCCCTCAGTCAGGCTTC-3′ (B) | −127 to +141 (2976844–2977111) |

Provided in the table for each lac fusion plasmid is information on primers used for PCR amplification of the indicated promoter fragment and the enzymes (B, BamHI; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SalI; and X, XbaI) used for cloning into plasmid vector pMU575 (1); the corresponding restriction sites in the primers are italicized.

The extent of each cloned insert region, relative to the start site of transcription most proximal to the coding region of the gene, is given; genomic coordinates for the cloned regions are from Rudd (40).

Construction of mutant encoding ArgP(P274S).

The argPd(P274S) mutant had previously been described by Celis (10) as one exhibiting dominant l-canavanine resistance but by a proposed mechanism different from that involving activation of argO transcription. Since all the other argPd mutations confer l-canavanine resistance by the latter mechanism alone (32), we sought to construct and test the P274S variant of ArgP in this study.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the argP+ gene on plasmid pHYD915 to argP(P274S) was done with the aid of the QuikChange kit and associated protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), using the complementary primer pairs 5′-GCACCGCTTTGCTTCTGAAAGCCGCAT-3′ and 5′-ATGCGGCTTTCAGAAGCAAAGCGGTGC-3′ (nucleotide substitutions are italicized). The resultant plasmid, designated pHYD2606, conferred dominant l-canavanine resistance in an argO+ strain but not in a ΔargO mutant (data not shown), confirming that this ArgP variant also works through ArgO in exhibiting its phenotype.

Microarray expression profiling.

For microarray expression profiling experiments, RNA preparations were made from the following pair of strains after growth to mid-exponential phase in glucose-minimal A medium with 1 mM Arg (relevant genotypes are in parentheses): (i) strain MC4100 carrying the plasmid pHYD926 encoding ArgPd(S94L) (argP+/argPd); and (ii) strain GJ9602 (ΔargP). The microarray data were generated at an outsourced facility (Genotypic Technology Pvt. Ltd., Bengaluru, India).

Other methods.

The protocols for EMSA experiments with purified ArgP protein bearing a C-terminal His6 tag (His6-ArgP) have been described earlier (26), and the reactions were performed in EMSA binding buffer of the following composition: 10 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol, and 5% glycerol. The DNA templates were obtained by PCR from E. coli genomic DNA with the various primer pairs listed in Table 2 and one additional control template (295-bp fragment from the lacZ locus, genomic coordinates 364776 to 365070 [40]) with the primer pair 5′-GTGGTGCAACGGGCGCTGGGTCGGTTAC-3′ and 5′-CAACTCGCCGCACATCTGAACTTCAG-3′; after 5′-end labeling, the PCR fragments were purified by electroelution following electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide gels (42).

Tolerance or sensitivity to l-canavanine was tested by the method given in Nandineni et al. (33), while resistance to thialysine was scored with 200-μg/ml supplementation in glucose-minimal A medium. Procedures for P1 transduction (31) and for PCR, in vitro DNA manipulations, and transformation (42) were as described previously. β-Galactosidase assays were performed by the method of Miller (31); each value reported is the average of at least three independent experiments, and the standard error was <10% of the mean in all cases.

RESULTS

Microarray profiling to identify candidate genes regulated by ArgP in vivo.

We initially undertook a microarray-based comparison of whole-genome mRNA abundances between an isogenic pair of strains that was either ΔargP (GJ9602) or expressed the dominant constitutively acting S94L variant of the ArgP protein in the argP+ strain (MC4100/pHYD926), which had been grown to exponential phase in Arg-supplemented glucose-minimal A medium. At the time that these experiments were done, the genes known to be ArgP regulated in vivo included the following (gene functions are indicated in parentheses): argO (Arg export), dapB (dihydrodipicolinate reductase in the diaminopimelate-Lys biosynthetic pathway), and K. pneumoniae gdhA (glutamate dehydrogenase for NH4+ assimilation and glutamate biosynthesis). All three genes are repressed upon growth in Lys-supplemented medium (7, 15, 32).

In the microarray expression experiments between the ΔargP and argPd(S94L) strains, the mRNA abundances of all three genes listed above exceeded the log2 difference threshold of 1.0, with values of 2.3, 2.7, and 1.3, respectively. Other genes implicated in Lys metabolism (36) that crossed this threshold were (gene function and log2-fold difference are in parentheses) lysP (Lys permease, 2.3), lysC (Lys-sensitive aspartokinase, 1.9), and asd (aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, 1.1).

Accordingly, the E. coli genes argO, dapB, gdhA, lysP, lysC, and asd were chosen for further analysis of in vivo regulation by the ArgP protein and its constitutive variants. Two additional genes, lysA (diaminopimelate decarboxylase) and dapD (tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase), were also included for the study, since both are repressed by Lys, as with the known ArgP-regulated genes (36).

Promoter-lac fusion studies in argP+ and argP mutants.

For each of the genes dapB, gdhA, lysP, lysC, asd, lysA and dapD, the upstream cis regulatory region was PCR amplified and cloned into pMU575, which is a single-copy-number IncW replicon plasmid vector for generating promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions (1). The equivalent argO-lac fusion derivative of pMU575 (pHYD1723) has been described earlier (26).

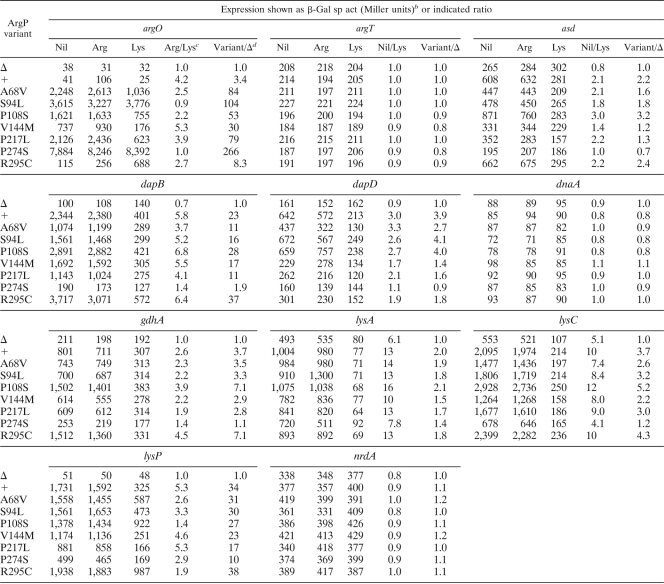

The eight lac fusion constructs were then introduced into a ΔargP strain carrying either argP+ or any of the constitutive argP mutant alleles on the pSC101-based plasmid vector pCL1920; similar derivatives of ΔargP with vector pCL1920 alone served as the negative controls in these experiments. β-Galactosidase assays were performed for cultures of the strains grown in medium without or with supplementation with Arg or Lys at 1 mM. The data from these experiments, presented in Table 3, permitted the following interpretations.

Table 3.

Expression of lac fusions in different argP variant derivativesa

Derivatives of the ΔargP strain GJ9602 each carrying two plasmids, as follows, were used in the experiments. (i) Plasmid vector pCL1920 (Δ) or its derivatives with argP+ (+; pHYD915) or the different argPd variants indicated. (ii) One of the following lac fusion plasmids: pHYD1723 (argO), pHYD2660 (argT), pHYD2668 (asd), pHYD2669 (dapB), pHYD2610 (dapD), pHYD2671 (dnaA), pHYD2602 (gdhA), pHYD2670 (lysA), pHYD2664 (lysC), pHYD2636 (lysP), or pHYD2672 (nrdA).

Specific activities of β-galactosidase (β-Gal) after growth in glucose-minimal A medium supplemented with 18 amino acids other than Arg or Lys (Nil), 18 amino acids and 1 mM Arg (Arg), or 18 amino acids and 1 mM Lys (Lys) are reported.

Data indicate the degree of Lys repression for the lac fusion strain concerned, relative to Arg supplementation in the case of argO and to Nil supplementation for the rest.

Data indicate the degree of regulation imposed by the ArgP variant concerned (or the wild-type ArgP) relative to that in the ΔargP strain, in medium with Arg supplementation in the case of argO and with Nil supplementation for the rest.

(i) Transcription from promoters of the genes gdhA, asd, dapB, dapD, and lysP in cultures of the argP+ strains grown in medium not supplemented with Arg or Lys is higher than that in the corresponding ΔargP derivatives, by factors of approximately 4, 2.5, 23, 4, and 35, respectively. Arg supplementation was without effect for any of these genes.

(ii) All the genes listed above also exhibited repression upon Lys supplementation in the argP+ but not the ΔargP strain, suggesting that Lys repression of their promoters is ArgP mediated. (iii) As has also been reported earlier (26, 32, 37), argO-lac expression was stimulated 4-fold in the argP+ strain relative to that in ΔargP but only in Arg-supplemented medium. Lys supplementation was associated with repression only in the argP+ strain.

(iv) The constitutive argP mutations that were used in this study had been selected to confer l-canavanine resistance (that is, for enhanced expression of ArgO, which is the exporter of Arg and l-canavanine) (10, 32); as expected, all of them displayed much higher levels of argO-lac expression than the argP+ strain without or with Arg or Lys supplementation. The P274S variant in particular was the most effective for constitutive argO expression (with a 270-fold degree of activation).

(v) In the case of the other ArgP-regulated genes discussed above, many of the argP constitutive mutations behaved much like the argP+ allele itself for both activation and Lys repression, although a few combinations exhibited differences; for example, the levels of activation obtained with the P108S variant at gdhA (7-fold) and lysC (5-fold) were higher than that with argP+ at these promoters, but P108S was also less effective for Lys repression of lysP, and both V144M and P217L were ineffective for activation of asd and dapD. However, the most conspicuous discrepancy was that seen with the P274S variant; although it was the most proficient of all the ArgPd mutants for constitutive argO expression, this variant was among the least effective for activation of expression from all the other ArgP-regulated promoters and, indeed, behaved like ΔargP at several of them (gdhA, asd, dapD, and lysC).

(vi) For lysC, there was a 5-fold repression by Lys in the ΔargP strain (that is, ArgP independent); this presumably represents the regulation imposed by the Lys-responsive riboswitch that is proposed to exist in the leader region of the lysC mRNA (39, 44). However, the argP+ strain displayed 4-fold higher expression in the unsupplemented medium than the ΔargP strain and 10-fold repression by Lys, suggestive of an additional component of control that was ArgP dependent. The argPd(P274S) mutant behaved like the ΔargP strain, whereas the other argPd derivatives exhibited the additional component of activated expression and Lys repression, as was obtained in the argP+ strain.

(vii) Along the same lines as with lysC, the expression of the lysA-lac fusion was repressed 6- to 8-fold in the ΔargP and argPd(P274S) mutants, which reflects the regulation conferred by the regulator protein LysR (see below). All other argPd derivatives, as well as the argP+ strain, showed 10- to 16-fold repression upon Lys supplementation.

EMSA studies with ArgP.

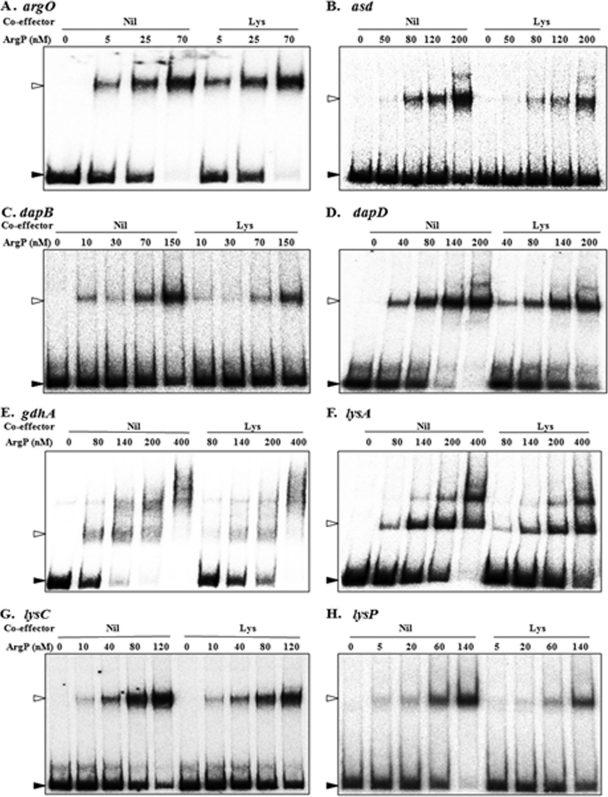

To determine whether the in vivo expression differences between argP+ and argP mutant strains for the various promoter-lac fusion constructs were associated with ArgP binding to the corresponding cis regulatory regions in vitro, we performed EMSA experiments as described below. Earlier studies have shown that ArgP-mediated Lys repression can occur by two alternative mechanisms at different promoters. At dapB or K. pneumoniae gdhA, ArgP binding to the regulatory region is diminished upon the addition of Lys (7, 15). At argO, on the other hand, Lys-liganded ArgP binds the regulatory region (7, 26, 37) but it then inhibits productive transcription at a step further downstream by trapping RNA polymerase at the promoter (26). Accordingly, in this study, EMSA experiments with His6-ArgP were done in the absence or presence of 0.1 mM Lys, and the cis regulatory regions of gdhA, lysC, dapB, dapD, asd, lysA, lysP, and argO were employed. The data from these experiments are shown in Fig. 1. The apparent dissociation constants (Kds) for binding of ArgP to the different templates in the presence or absence of Lys are given in Table 4.

Fig. 1.

EMSAs with ArgP and cis regulatory regions of different genes in the absence or presence of the coeffector Lys. ArgP monomer concentrations are indicated for each lane. Bands corresponding to free DNA and to DNA in binary complex with ArgP are marked by filled and open arrowheads, respectively.

Table 4.

Apparent Kds of ArgP binding to cis regulatory regions of different genesa

| cis regulatory region |

Kd (nM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| −Lys | +Lys | |

| argO | 15 | 15 |

| argT | >400 | >400 |

| asd | 170 | >200 |

| dapB | 120 | >150 |

| dapD | 70 | 120 |

| dnaA | 150 | 150 |

| gdhA | 80 | 130 |

| lysA | 150 | 210 |

| lysC | 70 | 110 |

| lysP | 55 | >140 |

| nrdA | 150 | 150 |

| lacZ | >400 | >400 |

From the EMSA autoradiograph for each of the DNA templates, the amounts of radioactivity in the bands corresponding to free (unbound) DNA were densitometrically determined for the different lanes, and the apparent Kd in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 0.1 mM Lys was calculated from the curve-plotting values of the unbound fraction versus the ArgP concentrations used.

Consistent with the data from earlier reports (7, 26, 37), ArgP exhibited high-affinity binding to argO (Kd = 15 nM) that was not diminished in the presence of Lys. Under identical experimental conditions as for argO, the regulatory regions of the other ArgP-regulated genes (asd, dapB, dapD, gdhA, lysA, lysC, and lysP) were also bound by ArgP, with apparent Kds ranging from 55 nM to 170 nM; in all these cases (unlike the situation with argO), the addition of Lys was associated with an increase in the apparent Kd, indicating that ArgP binding in these instances is Lys sensitive.

Coregulation of gdhA in vivo by both ArgP and NaCl.

In addition to its role in NH4+ assimilation, glutamate synthesis through the two pathways involving glutamate synthase on the one hand and glutamate dehydrogenase on the other (these are encoded by gltBD and gdhA, respectively) contribute to E. coli osmoregulation, that is, adaptation to growth at high osmolarity (13, 38). We found that gdhA-lac expression is reduced 3-fold upon growth in a medium rendered highly osmolar by NaCl supplementation; furthermore, the decrease in expression at high osmolarity was additive to that imposed by a ΔargP mutation, such that gdhA-lac transcription in the ΔargP mutant grown with NaCl supplementation was 10-fold lower than that in the wild-type strain grown without such supplementation (Table 5). Although the mechanism of gdhA transcriptional regulation by osmolarity remains to be determined, these data may provide an explanation for the earlier findings of Nandineni et al. (33) that the gltBD argP double mutants are growth inhibited at high osmolarity.

Table 5.

Regulation of gdhA expression by ArgP and NaCl

| Strain (genotype) | β-Gal sp act (Miller units)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| −NaCl | +NaCl | |

| MC4100 (argP+) | 1,016 | 331 |

| GJ9602 (ΔargP) | 340 | 102 |

Values reported are the specific activities of β-galactosidase (β-Gal) in derivatives of the indicated strains carrying gdhA-lac on plasmid pHYD2602 after growth in glucose-minimal A medium without (−NaCl) or with (+NaCl) supplementation with 0.4 M NaCl and 1 mM glycine betaine.

Analysis of lysP regulation by ArgP.

The results described above indicated that ArgP binds the lysP regulatory region to mediate its nearly 35-fold transcriptional activation and that the absence of such ArgP binding either in ΔargP mutants or upon Lys supplementation in argP+ strains results in very low levels of lysP expression. In support of this conclusion was our finding that the ΔargP strain is resistant to the Lys analog thialysine to the same extent (200 μg/ml) as a ΔlysP mutant (data not shown).

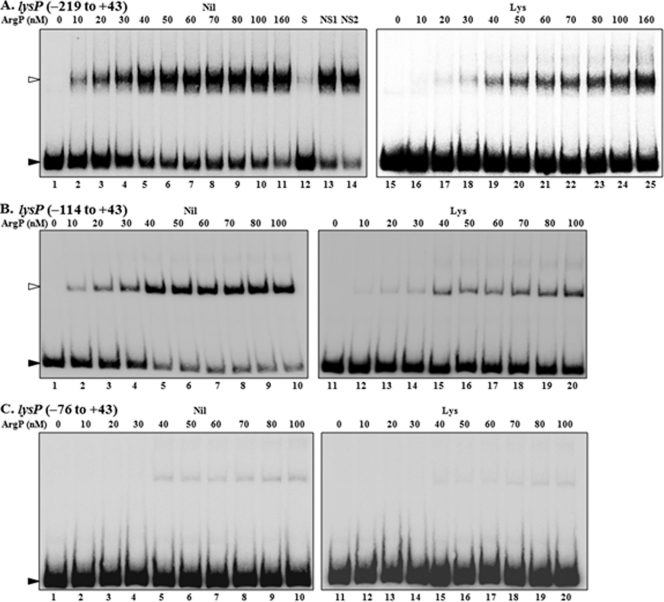

Recently, Ruiz et al. (41) had also independently identified ArgP's role both as a transcriptional activator and in mediating the repression of the lysP gene by Lys. However, they reported that ArgP binds the lysP regulatory region with similar affinities in both the absence and presence of Lys and had accordingly suggested that ArgP mediates Lys repression of lysP by the same mechanism of RNA polymerase trapping that it does at argO. Since our results were different from those of Ruiz et al. (41), we repeated the EMSA experiments with lysP, using a graded series of ArgP concentrations in the absence or presence of Lys (Fig. 2A); the data clearly establish that binding of ArgP to the lysP template is Lys sensitive. The specificity of ArgP's binding to labeled lysP was also established in this experiment (Fig. 2A), by demonstrating that it could be competed by unlabeled lysP DNA (lane 12) but not by two other nonspecific DNA fragments (lanes 13 and 14).

Fig. 2.

EMSAs with ArgP and the full-length cis regulatory region of lysP (A) or one of its two deletion derivatives (B, C) in the absence (Nil) or presence (Lys) of the coeffector Lys. The extent in base pairs of the lysP regulatory region used in each experiment is given in parentheses. ArgP monomer concentrations are indicated for each lane. Bands corresponding to free DNA and to DNA in binary complex with ArgP (the latter is not observed in panel C) are marked by filled and open arrowheads, respectively. Lanes 12 to 14 of panel A depict the results of the addition of a 100-fold excess of unlabeled competitor DNA, either specific, that is the full-length lysP fragment (S), or one of two different nonspecific DNA fragments (NS1 and NS2), to the mixtures for EMSA reactions undertaken with 160 nM ArgP. NS1 is a 253-bp fragment from the ilvG locus obtained by PCR with the primers 5′-CAGCAACACTGCGCGCAGCTGCGTGATG-3′ and 5′-CTTGTGCGCCAACCGCCGCCGGTAAAC-3′ (genomic coordinates 3949570 to 3949822 [40]), while NS2 is the same 295-bp lacZ fragment that was used for the EMSA whose results are shown in Fig. 3.

When nested deletion constructs of the lysP regulatory region were tested, a fragment extending upstream up to −114 bp (relative to the start site of transcription) was nearly indistinguishable from the larger fragment (extending up to −219 bp) in terms of both in vivo lac fusion regulation (Table 6) and in vitro Lys-sensitive ArgP binding (Fig. 2, compare panels A and B). On the other hand, a smaller fragment, extending up to −76 bp, was inactive for lac fusion expression in vivo (Table 6) and lysP binding in vitro (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the lysP upstream region between −114 bp and −76 bp carries critical sequence determinants for binding of and regulation by ArgP.

Table 6.

ArgP regulation of lac fusions to nested deletions of lysP

| Plasmid (lysP extent)a | β-Gal sp act (Miller units)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

argP+ strain |

ΔargP strain |

|||

| Nil | Lys | Nil | Lys | |

| pHYD2636 (−219 to +32) | 802 | 150 | 31 | 30 |

| pHYD2647 (−114 to +32) | 852 | 122 | 52 | 50 |

| pHYD2648 (−76 to +32) | 43 | 47 | 41 | 42 |

Extents of lysP shown are in base pairs relative to the start site of transcription.

Values reported are the specific activities of β-galactosidase (β-Gal) in derivatives of MC4100 (argP+) or GJ9602 (ΔargP) carrying the indicated lysP-lac fusion plasmids after growth in glucose-minimal A without (Nil) or with (Lys) Lys supplementation at 1 mM.

ArgP and cadBA regulation.

The LysP permease has also been implicated in transcriptional regulation of the cadBA operon encoding Lys decarboxylase. cadBA expression is induced only in medium of low pH that is also supplemented with Lys and is dependent on an activator, CadC. In lysP-defective mutants, cadBA is induced at low pH even in the absence of Lys, and the model is that LysP negatively regulates cadBA by sequestering CadC in the absence of Lys (34, 45). Since our findings indicated that ArgP is needed for activation of lysP transcription, we tested whether cadBA expression would be rendered Lys independent even in the ΔargP mutant.

Accordingly, a cadBA-lac fusion was constructed and shown to exhibit regulation by cadC, lysP, low pH, and Lys as reported earlier (34, 45); however, the ΔargP mutant failed to phenocopy the ΔlysP strain, in that cadBA expression continued to be Lys dependent in the former (Table 7). These data suggest that the basal level of LysP permease present in a ΔargP strain is sufficient for the negative regulation of cadBA in the absence of Lys.

Table 7.

Effects of CadC, LysP, and ArgP on cadBA-lac expression

| Strain (genotype) | β-Gal sp act (Miller units)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.4 |

pH 5.8 |

|||

| Nil | Lys | Nil | Lys | |

| MC4100 (wild type) | 25 | 28 | 24 | 98 |

| GJ9623 (ΔlysP) | 27 | 27 | 94 | 96 |

| GJ9647 (ΔcadC) | 25 | 26 | 26 | 24 |

| GJ9602 (ΔargP) | 23 | 22 | 26 | 96 |

| GJ9649 (ΔlysP ΔcadC) | 21 | 28 | 24 | 26 |

| GJ9648 (ΔargP ΔcadC) | 25 | 26 | 24 | 28 |

| GJ9624 (ΔargP ΔlysP) | 27 | 24 | 87 | 99 |

Values reported are the specific activities of β-galactosidase (β-Gal) in the indicated strain derivatives carrying the cadBA-lac fusion plasmid pHYD2674 after growth in minimal A-based medium of pH 7.4 or pH 5.8 supplemented with either 19 amino acids other than Lys (Nil) or 19 amino acids and 10 mM Lys (Lys).

Testing for cross-regulation by LysR and ArgP genes.

As mentioned above, ArgP belongs to the LTTR family, of which LysR is the prototypic member (30). Since both LysR and ArgP are involved in mediating the repression by Lys of different genes, we tested for the possibility of cross-regulation by the two transcription factors in vivo.

A ΔlysR strain fails to express lysA and hence is a Lys auxotroph (36). Therefore, to test for regulation in the presence or absence of Lys in the ΔlysR mutant, we constructed derivatives in which lysA was ectopically expressed from the Para promoter on a plasmid (pHYD2673). The LysR-regulated lysA-lac and ArgP-regulated lysP-lac fusions were employed for tests of in vivo cross-regulation (by ArgP and LysR, respectively); the data reported in Table 8 indicate that there is no cross-regulation of lysP by LysR and that ArgP's ability to activate lysA occurs only in a lysR+ background. The expression of a lysR-lac fusion was also unaffected in a ΔargP strain, although it was increased 2-fold in a ΔlysR mutant (Table 8), indicative of negative autoregulation (36).

Table 8.

Tests for cross-regulation by ArgP and LysR

| Strain (genotype) | β-Gal sp act (Miller units)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

lysA-lac with: |

lysR-lac with: |

lysP-lac with Nil | |||||

| Nil | Arg | Lys | Nil | Arg | Lys | ||

| GJ9650 (wild type) | 215 | 300 | 68 | 30 | 33 | 33 | 1,004 |

| GJ9651 (ΔargP) | 72 | 75 | 29 | 29 | 33 | 34 | 49 |

| GJ9652 (ΔlysR) | 23 | 26 | 22 | 59 | 65 | 63 | 1,052 |

| GJ9653 (ΔargP ΔlysR) | 24 | 23 | 25 | 66 | 66 | 65 | 49 |

Values reported are the specific activities of β-galactosidase in derivatives of the indicated strains carrying both the Para-lysA plasmid pHYD2673 and one of the following plasmids: pHYD2670 (lysA-lac), pHYD2675 (lysR-lac), or pHYD2636 (lysP-lac). Strains were grown in minimal A medium supplemented with 0.2% each of glycerol and l-arabinose along with one of the following: 18 amino acids other than Arg and Lys (Nil), 18 amino acids and 1 mM Arg (Arg), or 18 amino acids and 1 mM Lys (Lys).

Genes for Arg import are not regulated by ArgP.

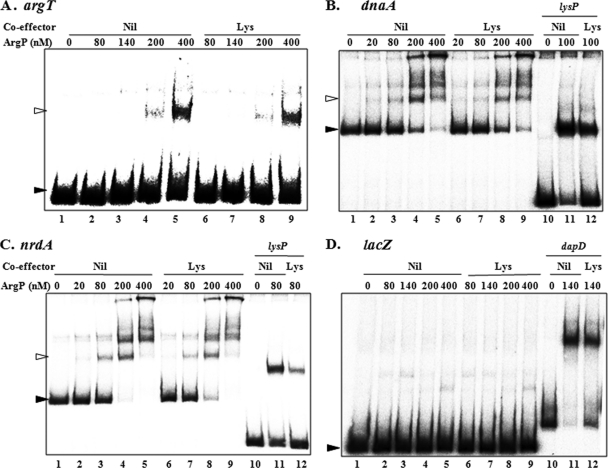

Since ArgP is required for transcription of the Arg exporter ArgO, we also tested the promoters of other genes known to be involved in Arg transport (artP, artJ, argT, and the hisJQMP operon) as candidates for regulation by ArgP. The respective promoter-lac fusions were constructed, but neither the ΔargP mutation nor Lys supplementation affected the expression of any of them (Table 9). Consistent with earlier reports (8, 9), the lac fusions with the promoters of hisJ, artJ, and artP exhibited repression by Arg in the wild-type strain and derepressed expression in a ΔargR mutant (Table 9). EMSA experiments undertaken with the regulatory region of one of the genes, argT, revealed a very low affinity of binding by ArgP that was Lys independent (Fig. 3 and Table 4); the expression of the argT-lac fusion was also not affected in any of the argPd mutants (Table 3).

Table 9.

Tests for ArgP regulation of genes related to Arg transport

| Plasmid (genotype) | β-Gal sp act (Miller units)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type strain with: |

ΔargP strain with: |

argR with Arg | |||||

| Nil | Arg | Lys | Nil | Arg | Lys | ||

| pHYD2658 (artJ-lac) | 1,353 | 286 | 1,480 | 1,256 | 231 | 1,252 | 1,700 |

| pHYD2659 (artP-lac) | 170 | 105 | 197 | 184 | 122 | 210 | 190 |

| pHYD2660 (argT-lac) | 249 | 279 | 242 | 279 | 255 | 221 | 198 |

| pHYD2661 (hisJ-lac) | 227 | 115 | 262 | 244 | 114 | 296 | 289 |

Values reported are the specific activities of β-galactosidase in derivatives of MC4100 (wild type), GJ9602 (ΔargP), and GJ4748 (argR) carrying the indicated lac fusion plasmid after growth in glucose-minimal A medium without (Nil) or with supplementation with Arg or Lys at 1 mM.

Fig. 3.

EMSAs with ArgP and cis regulatory regions of different genes in the absence or presence of the coeffector Lys. ArgP monomer concentrations are indicated for each lane. Bands corresponding to free DNA and to DNA in binary complex with ArgP (the latter is not observed for lacZ) are marked by filled and open arrowheads, respectively. Lanes 10 to 12 in panels B to D represent the results of control EMSA reactions with lysP (full-length) or dapD templates as marked.

ArgP and regulation of genes of DNA replication and metabolism.

In its description as IciA, ArgP has been reported to regulate dnaA and nrdA transcription (20, 27–29). We constructed and tested the promoter-lac fusions for both these genes, but neither was altered in expression in the ΔargP or argPd mutants compared to its expression in the argP+ strain, either without or with Lys supplementation (Table 3). Our conclusion runs contrary to that of Han et al. (20), who overproduced IciA (ArgP) and employed an RNase protection assay to show that nrdA transcription is ArgP regulated in vivo. In EMSA experiments using ArgP and the cis regulatory regions of both dnaA and nrdA, we observed binding at an apparent Kd of around 150 nM that was unchanged in the presence or absence of Lys (Fig. 3 and Table 4).

Finally, since our data showed that ArgP binds several DNA templates in vitro without a corresponding regulatory effect in vivo, we asked whether at high concentrations it would exhibit binding to a completely nonspecific control DNA fragment. When tested by EMSA, negligible binding of ArgP was observed even at 400 nM to an internal 295-bp DNA sequence from lacZ (Fig. 3 and Table 4). These findings are consistent with other reports that ArgP does not bind DNA nonspecifically (23, 41), as also with both the inability of nonspecific DNA fragments to compete with lysP for binding to ArgP (Fig. 2) and the very weak binding of ArgP to argT (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The Arg exporter ArgO was among the first whose expression in vivo was identified as being under the transcriptional control of the LTTR ArgP, and the argPd mutants were obtained as derivatives with greatly elevated argO expression (32). In the case of argO, ArgP mediates its transcriptional activation by Arg, as well as its repression by Lys (7, 26, 32, 37); the latter is achieved by a mechanism involving the active trapping at the argO promoter by ArgP of RNA polymerase, which is then prevented from being released to engage in productive transcription (26). Subsequently, dapB and K. pneumoniae gdhA have also been shown to be ArgP regulated and to be repressed with Lys; in both these instances, Lys repression is achieved by reduced binding of ArgP to the DNA regulatory regions in the presence of Lys (7, 15).

In the present work, we have constructed lac fusions to promoters of genes connected with Arg or Lys metabolism and transport and studied them in the argP+, ΔargP, and argPd strains to identify several new ArgP-regulated genes in vivo. These include lysP, lysC, lysA, dapD, and asd (in addition to argO, dapB, and gdhA), all of which exhibited ArgP-mediated repression upon Lys supplementation in vivo, as well as ArgP binding to the corresponding cis regulatory regions in vitro.

Insights from the use of argPd mutants.

For many of the newly identified targets of ArgP listed above, the magnitude of in vivo regulation by ArgP (and of repression by Lys) was only around 3-fold, and it was the data on lac fusion expression in the argPd mutants that offered additional confidence that this regulation was indeed real.

Although the argPd mutants had been obtained (10, 32) on the basis of their resistance to l-canavanine and increased expression in them of argO, the mutants exhibited different effects on the other target genes with regard both to the degree of activation relative to that in the ΔargP strain and to the degree of repression upon Lys supplementation (Table 3). Of these, the most significant difference was that for the P274S variant, which was almost completely defective for activation of lysC, asd, dapD, gdhA, and dapB and partially so for lysP, whereas it was indeed the most effective of all the argPd mutants for argO activation. On the other hand, for the genes such as argT, dnaA, or nrdA that are not ArgP regulated, there was no difference in expression between the ΔargP derivative and any of the argPd mutants.

The expression data with the argPd mutants also indirectly illustrate the complexity of ArgP's binding interactions with and at the cis regulatory regions of its target genes, since the mutations appear to affect these interactions differently at different targets.

Regulation by ArgP of Lys-biosynthetic genes.

Of the ArgP-regulated and Lys-repressed genes identified earlier and in this study, five encode enzymes for biosynthesis of diaminopimelic acid and Lys (36): two in the pathway that is common for Lys, threonine, and methionine biosynthesis (lysC and asd) and three in the Lys-specific pathway (dapB, dapD, and lysA). Of these, lysC and lysA exhibit additional mechanisms for Lys repression, involving, respectively, a postulated riboswitch (39, 44) and the LysR regulator protein (30, 36).

Our results indicate that ArgP activates lysA transcription 2-fold but only in cells that are also proficient for LysR. On the other hand, ArgP-mediated regulation of lysC is independent of and additive to the putative riboswitch regulatory mechanism. One may speculate that Lys-dependent modulation by ArgP of multiple genes of the pathway provides a fine-tuning effect in controlling the flux of intermediates serving the biosynthesis of three different amino acids for protein synthesis, as also of diaminopimelic acid for peptidoglycan assembly.

Role for ArgP in Lys-mediated repression in E. coli.

As mentioned above, all genes so far identified to be ArgP mediated are repressed by Lys, and we suggest that all Lys-liganded repression is mediated by ArgP in E. coli. LysR also mediates Lys repression (of lysA), but in this case it has been suggested that the coeffector ligand is diaminopimelic acid (which is the substrate for lysA) and that the latter's binding to LysR converts it into its activator conformation (30, 36). Although Lys-liganded repression is a common feature of all the ArgP-regulated genes, different mechanisms operate to achieve such repression at different genes, as discussed below.

Regulation of lysP by ArgP.

Of the various ArgP-regulated genes, the three that exhibited >10-fold activation were argO, dapB, and lysP. The lysP gene encodes a Lys-specific permease, and our data indicate that it is around 35-fold activated by ArgP and 5-fold repressed by Lys; a ΔargP mutant phenocopies a ΔlysP mutant for resistance to the Lys analog thialysine. LysR does not participate in lysP transcriptional regulation. In vitro, ArgP binds the lysP regulatory region with a Kd of around 55 nM and the binding affinity is diminished upon the addition of Lys (to a Kd of >140 nM), suggesting that Lys represses lysP in vivo by engendering the loss of ArgP binding to the lysP operator region. The in vitro data also indicate that the lysP upstream sequence between −76 bp and −114 bp is required for ArgP binding.

In addition to its role in active uptake of Lys, the LysP permease also participates in Lys-dependent transcriptional regulation of the cadBA operon, by sequestering the CadC activator in the absence of Lys but not in its presence (34, 45). We found in this study that the ΔargP mutant does not phenocopy a ΔlysP mutant for cadBA expression, suggesting that the basal level of LysP which is present in a ΔargP strain is sufficient for mediating the sequestration of CadC in cadBA regulation.

While this work was being completed, Ruiz et al. (41) independently reported the identification of lysP as a Lys-repressed transcriptional target of ArgP. While most of our results on lysP are similar to those of Ruiz et al. (41), one important difference is their description that ArgP's binding to the lysP regulatory region in vitro is Lys insensitive (and therefore similar to ArgP's binding to argO), whereas we found that it is Lys sensitive. Perhaps this discrepancy may be related to differences in the protocols employed in the two laboratories for ArgP purification or the subsequent protein-DNA binding studies, although we emphasize that our demonstration of Lys-sensitive binding of ArgP to lysP was made under the identical conditions in which ArgP's binding to argO was Lys insensitive (Fig. 1).

Unique features of argO regulation by ArgP.

Of the different genes under the control of ArgP in vivo, argO appears to be unique in at least two ways in its manner of regulation. First, it is the only gene that requires Arg as a coeffector for its activation. Second, it is also the only example in which ArgP's binding to the cis regulatory region is not Lys sensitive, so that repression by Lys is achieved by an RNA polymerase-trapping mechanism at the argO promoter.

The differences between argO and the other target genes with regard to the features of their regulation by ArgP are also reflected in their differential responses to the argPd mutations (although it must be noted that these mutations were selected on the basis of their ability to confer greatly increased argO expression). Perhaps the most prominent distinction is that obtained with the P274S variant of ArgP, as discussed above.

Thus, it appears that the mechanism of regulation of argO by ArgP is fundamentally different from that of the other genes regulated by this protein. At the same time, it is noteworthy that two of the genes that are most prominently regulated by ArgP, argO and lysP, are both also regulated by the leucine-responsive general transcriptional regulator Lrp (37, 41).

dnaA and nrdA are not regulated by ArgP in vivo.

In its proposed avatar as IciA, ArgP has been reported to bind oriC in both E. coli (21–23, 46) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (25) and to regulate transcription from promoters of the dnaA and nrdA genes (20, 27–29). We found that ArgP does bind to the regulatory regions of dnaA and nrdA in vitro with moderate affinity but that it does not regulate their transcription in vivo. Thus, we believe that ArgP does not play a role in transactions involving DNA metabolism or replication in E. coli, which conclusion is supported by the facts that neither a ΔargP mutant nor an ArgP-overproducing strain is compromised for DNA replication or growth rate (46).

ArgP as a noncanonical transcriptional regulator.

Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation studies have been described recently for a number of transcriptional regulators in E. coli, according to which several, such as MelR (17, 18), MntR (49), NsrR (35), and PurR (12), behave canonically in that each exhibits binding at sites where it serves to control transcription of the adjacent genes or operons. Lrp also appears to be a canonical transcriptional regulator, although it binds nearly 140 sites in the genome (11).

On the other hand, DNA binding by the activator protein C-reactive protein (CRP) is apparently noncanonical, since there are about 70 sites where it binds strongly and exerts its transcriptional regulatory function and a further approximately 104 sites of low-affinity binding (17). CRP's behavior contrasts with that of its closely related paralog FNR, which binds canonically at around 65 locations without any noise of low-affinity binding (16). Another example of noncanonical binding is RutR, many of whose binding sites fall within gene coding regions (43).

Our studies would suggest that the ArgP or IciA protein is also a noncanonical transcriptional regulator, in that it does exhibit specific DNA binding to mediate the transcriptional regulation of particular genes in vivo, but in addition, it also binds at other sites in the genome that are not associated with regulatory outcomes. The purpose of the latter category of binding by ArgP remains to be determined. It has been speculated in the case of CRP that by bending the DNA at its noncanonical binding sites, the protein may contribute to chromosome shaping and chromatin compaction (17, 47). ArgP too may similarly participate in shaping the nucleoid architecture, given its reported propensity to bind curved DNA (2). It is also possible that the putative dual functions of ArgP, in transcriptional regulation and in chromosome organization, are in some way related to its ability to dimerize in two different modes (as deduced from the crystal structure of the M. tuberculosis ortholog) (50).

Finally, it is noteworthy that many of the genes regulated by ArgP are controlled also by other mechanisms, such as by LysR for lysA, osmolarity for gdhA, the riboswitch for lysC, and Lrp for argO and lysP. These results therefore lend support to the notion that multitarget regulators and multifactor promoters represent the norm in bacterial gene regulation (24).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Laboratory of Bacterial Genetics for their advice and discussions.

C.N.M. and J.G. are recipients, respectively, of a doctoral Research Fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research and the J. C. Bose Fellowship from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. This work was supported by a Centre of Excellence in Microbial Biology research grant from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andrews A. E., Dickson B., Lawley B., Cobbett C., Pittard A. J. 1991. Importance of the position of TYR R boxes for repression and activation of the tyrP and aroF genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:5079–5085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azam T. A., Ishihama A. 1999. Twelve species of the nucleoid-associated protein from Escherichia coli. Sequence recognition specificity and DNA binding affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33105–33113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Azam T. A., Iwata A., Nishimura A., Ueda S., Ishihama A. 1999. Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J. Bacteriol. 181:6361–6370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baba T., et al. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellmann A., et al. 2001. Expression control and specificity of the basic amino acid exporter LysE of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiology 147:1765–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berlyn M. K. 1998. Linkage map of Escherichia coli K-12, edition 10: the traditional map. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:814–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bouvier J., Stragier P., Morales V., Remy E., Gutierrez C. 2008. Lysine represses transcription of the Escherichia coli dapB gene by preventing its activation by the ArgP activator. J. Bacteriol. 190:5224–5229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caldara M., Charlier D., Cunin R. 2006. The arginine regulon of Escherichia coli: whole-system transcriptome analysis discovers new genes and provides an integrated view of arginine regulation. Microbiology 152:3343–3354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caldara M., Minh P. N., Bostoen S., Massant J., Charlier D. 2007. ArgR-dependent repression of arginine and histidine transport genes in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Mol. Biol. 373:251–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Celis R. T. 1999. Repression and activation of arginine transport genes in Escherichia coli K 12 by the ArgP protein. J. Mol. Biol. 294:1087–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cho B. K., Barrett C. L., Knight E. M., Park Y. S., Palsson B. O. 2008. Genome-scale reconstruction of the Lrp regulatory network in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19462–19467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cho B. K., et al. 2011. The PurR regulon in Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:6456–6464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Csonka L. N., Epstein W. 1996. Osmoregulation, p. 1210–1223 In Neidhardt F. C., et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 14. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goss T. J. 2008. The ArgP protein stimulates the Klebsiella pneumoniae gdhA promoter in a lysine-sensitive manner. J. Bacteriol. 190:4351–4359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grainger D. C., Aiba H., Hurd D., Browning D. F., Busby S. J. 2007. Transcription factor distribution in Escherichia coli: studies with FNR protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:269–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grainger D. C., Hurd D., Harrison M., Holdstock J., Busby S. J. 2005. Studies of the distribution of Escherichia coli cAMP-receptor protein and RNA polymerase along the E. coli chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:17693–17698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grainger D. C., et al. 2004. Genomic studies with Escherichia coli MelR protein: applications of chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 186:6938–6943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guzman L. M., Belin D., Carson M. J., Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han J. S., Kwon H. S., Yim J. B., Hwang D. S. 1998. Effect of IciA protein on the expression of the nrd gene encoding ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase in E. coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 259:610–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hwang D. S., Kornberg A. 1990. A novel protein binds a key origin sequence to block replication of an E. coli minichromosome. Cell 63:325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hwang D. S., Kornberg A. 1992. Opposed actions of regulatory proteins, DnaA and IciA, in opening the replication origin of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:23087–23091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hwang D. S., Thony B., Kornberg A. 1992. IciA protein, a specific inhibitor of initiation of Escherichia coli chromosomal replication. J. Biol. Chem. 267:2209–2213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishihama A. 2010. Prokaryotic genome regulation: multifactor promoters, multitarget regulators and hierarchic networks. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:628–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kumar S., Farhana A., Hasnain S. E. 2009. In-vitro helix opening of M. tuberculosis oriC by DnaA occurs at precise location and is inhibited by IciA like protein. PLoS One 4:e4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laishram R. S., Gowrishankar J. 2007. Environmental regulation operating at the promoter clearance step of bacterial transcription. Genes Dev. 21:1258–1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee Y., Lee H., Yim J., Hwang D. 1997. The binding of two dimers of IciA protein to the dnaA promoter 1P element enhances the binding of RNA polymerase to the dnaA promoter 1P. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3486–3489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee Y. S., Hwang D. S. 1997. Occlusion of RNA polymerase by oligomerization of DnaA protein over the dnaA promoter of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272:83–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee Y. S., Kim H., Hwang D. S. 1996. Transcriptional activation of the dnaA gene encoding the initiator for oriC replication by IciA protein, an inhibitor of in vitro oriC replication in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 19:389–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maddocks S. E., Oyston P. C. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154:3609–3623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nandineni M. R., Gowrishankar J. 2004. Evidence for an arginine exporter encoded by yggA (argO) that is regulated by the LysR-type transcriptional regulator ArgP in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:3539–3546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nandineni M. R., Laishram R. S., Gowrishankar J. 2004. Osmosensitivity associated with insertions in argP (iciA) or glnE in glutamate synthase-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:6391–6399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neely M. N., Dell C. L., Olson E. R. 1994. Roles of LysP and CadC in mediating the lysine requirement for acid induction of the Escherichia coli cad operon. J. Bacteriol. 176:3278–3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Partridge J. D., Bodenmiller D. M., Humphrys M. S., Spiro S. 2009. NsrR targets in the Escherichia coli genome: new insights into DNA sequence requirements for binding and a role for NsrR in the regulation of motility. Mol. Microbiol. 73:680–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patte J.-C. 1996. Biosynthesis of threonine and lysine, p. 528–541 In Neidhardt F. C., et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peeters E., Le Minh P. N., Foulquie-Moreno M., Charlier D. 2009. Competitive activation of the Escherichia coli argO gene coding for an arginine exporter by the transcriptional regulators Lrp and ArgP. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1513–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reitzer L. 6 July 2004, posting date Module 3.6.1.3, Biosynthesis of glutamate, aspartate, asparagine, l-alanine, and d-alanine. In Curtiss R., III, et al. (ed.), EcoSal Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC: doi:10.1128/ecosal.3.6.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodionov D. A., Vitreschak A. G., Mironov A. A., Gelfand M. S. 2003. Regulation of lysine biosynthesis and transport genes in bacteria: yet another RNA riboswitch? Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6748–6757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rudd K. E. 1998. Linkage map of Escherichia coli K-12, edition 10: the physical map. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:985–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruiz J., Haneburger I., Jung K. 2011. Identification of ArgP and Lrp as transcriptional regulators of lysP, the gene encoding the specific lysine permease of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 193:2536–2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sambrook J., Russell D. W. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shimada T., Ishihama A., Busby S. J., Grainger D. C. 2008. The Escherichia coli RutR transcription factor binds at targets within genes as well as intergenic regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:3950–3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sudarsan N., Wickiser J. K., Nakamura S., Ebert M. S., Breaker R. R. 2003. An mRNA structure in bacteria that controls gene expression by binding lysine. Genes Dev. 17:2688–2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tetsch L., Koller C., Haneburger I., Jung K. 2008. The membrane-integrated transcriptional activator CadC of Escherichia coli senses lysine indirectly via the interaction with the lysine permease LysP. Mol. Microbiol. 67:570–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thony B., Hwang D. S., Fradkin L., Kornberg A. 1991. iciA, an Escherichia coli gene encoding a specific inhibitor of chromosomal initiation of replication in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:4066–4070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wade J. T., Struhl K., Busby S. J., Grainger D. C. 2007. Genomic analysis of protein-DNA interactions in bacteria: insights into transcription and chromosome organization. Mol. Microbiol. 65:21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wei T., Bernander R. 1996. Interaction of the IciA protein with AT-rich regions in plasmid replication origins. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1865–1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yamamoto K., Ishihama A., Busby S. J., Grainger D. C. 2011. The Escherichia coli K-12 MntR miniregulon includes dps, which encodes the major stationary-phase DNA-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 193:1477–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhou X., et al. 2010. Crystal structure of ArgP from Mycobacterium tuberculosis confirms two distinct conformations of full-length LysR transcriptional regulators and reveals its function in DNA binding and transcriptional regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 396:1012–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]