Abstract

Human endogenous retrovirus (HERV)-specific T cell responses in HIV-1-infected adults have been reported. Whether HERV-specific immunity exists in vertically HIV-1-infected children is unknown. We performed a cross-sectional analysis of HERV-specific T cell responses in 42 vertically HIV-1-infected children. HERV (-H, -K, and -L family)-specific T cell responses were identified in 26 of 42 subjects, with the greatest magnitude observed for the responses to HERV-L. These HERV-specific T cell responses were inversely correlated with the HIV-1 plasma viral load and positively correlated with CD4+ T cell counts. These data indicate that HERV-specific T cells may participate in controlling HIV-1 replication and that certain highly conserved HERV-derived proteins may serve as promising therapeutic vaccine targets in HIV-1-infected children.

TEXT

Studies of HIV-1 pathogenesis in vertically HIV-1-infected infants before the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART) showed persistently high levels of plasma viremia for the first year of life, followed by a decline in viral burden by the age of three (18, 19). Moreover, a higher proportion of HIV-1-infected infants exhibited rapid disease progression to AIDS and death than that seen for adults (22). While remarkable progress has been made toward wider access to antiretroviral drugs, the majority of HIV-1-infected children worldwide remain untreated, resulting in high mortality rates among HIV-1-infected children less than 5 years of age.

Vertical transmission rates in the United States declined by over two-thirds with the introduction in 1994 of perinatal zidovudine (ZDV) prophylaxis, as per the ACTG 076 protocol (5, 27). Further reductions in transmission, to less than 2%, have been achieved with more effective antenatal and perinatal chemoprophylactic regimens and improved obstetric practices (14, 27). However, despite the availability of potent drugs, HIV-1-infected infants and children continue to have difficulty controlling plasma viremia due to multiple factors unique to pediatrics, including drug formulation and palatability issues, altered pharmacokinetics, novel toxicities, and caregiver-related problems. These obstacles have led to high levels of drug resistance among these patients, limiting future treatment options and increasing the financial and social costs of treating this disease.

The human genome is littered with retroviral gene elements known as human endogenous retroviruses (HERV). HERV comprise around 8 to 10% of the entire human genome and are thought to represent footprints of ancient retroviral infections which incorporated into germ line DNA (26). There are three separate classes of HERV, each of which is further subdivided into different families. Most HERV are defective due to the accumulation of mutations and deletions. However, some HERV families, e.g., HERV-H, HERV-W, HERV-K, and HERV-L, possess intact open reading frames encoding structural gene products (1, 3, 8, 15, 16) and are able to express these and other viral products under certain conditions (4, 13). In addition, some HERV have been shown to be associated with some autoimmune diseases and cancers (20, 21). In certain circumstances, exogenous retrovirus infections such as HIV-1 have been shown to induce HERV-K expression (6, 7, 11). We have previously shown that HIV-1-infected adults can mount anti-HERV-specific T cell responses and that an inverse relationship exists between the magnitude of the HERV-specific T cell response and the level of HIV-1 viremia in untreated patients, in both the early (10) and the chronic (23) phases of the disease. This finding suggests that HERV-specific immunity may be contributing to the control of viral replication in adults. The purpose of this study was to determine whether vertically HIV-1-infected children can also mount an anti-HERV response.

We performed a cross-sectional study to investigate HERV-specific T cell responses in 42 vertically HIV-1-infected patients. Study subjects were recruited from a large outpatient pediatric HIV-1 clinic located at Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, NY (Table 1). We obtained heparinized blood samples with appropriate informed consent under approval from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and Jacobi Medical Center institutional review board (IRB) committees. All patients were self-identified as African American or Hispanic. The plasma HIV-1 RNA load was measured with an Amplicor HIV-1 monitor (Roche Diagnostic Systems), which has a lower limit of quantification of 50 copies of viral RNA/ml. HERV and HIV-1 peptides were manufactured as described previously (10). Cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from study participants were thawed and screened for responses against a set of 28 HERV peptides (10) using a gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay (24, 23). All samples were tested in duplicate (at 105 cells per well) with the peptides at a concentration of 100 μg/ml per well. The high peptide concentration was used in the ELISPOT assays to detect low-avidity responses. This concentration elicited responses in the range of 50 to 715 spots per 106 PBMC. The numbers of spots for duplicate wells were averaged and normalized to numbers of IFN-γ-secreting spot-forming units (SFU) per 1 × 106 PBMC. The spot values from medium control wells were subtracted, after which a response was considered positive if it was >50 spots per million PBMC and >2 times higher than that in the background medium. HLA restriction was performed using patient-derived PBMC plus peptide-pulsed or unpulsed single-HLA allele B cell transfectants as targets in the ELISPOT assay. HLA typing was performed using an All Set HLA typing kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR).

Table 1.

Subject demographics and disease characteristicsa

| Parameter | Median value (IQR) or no. (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Median age (yr) | 14.7 (12.4–17.8) |

| Male/female | 21 (50%)/21 (50%) |

| Race | |

| Black | 26 (62%) |

| Hispanic | 16 (38%) |

| Disease characteristics | |

| 1994 CDC class | |

| N (none) | 4 (9.5%) |

| A (mild) | 16 (38%) |

| B (moderate) | 16 (38%) |

| C (AIDS defining) | 6 (14.5%) |

| CD4 cells (%) | 28 (17.8–31.5) |

| CD4 cell count (cells/μl) | 502 (354–1,762) |

| HIV-1 RNA (copies/ml) | 4,898 (567–34,250) |

| Antiretroviral therapy | |

| NRTIs | 12 (28.6%) |

| NRTIs + NNRTIs | 5 (12%) |

| NRTIs + PI | 18 (43%) |

| Complex ART (≥3 classes) | 7 (16.4%) |

Data are median values(IQR) and numbers(%). NRTIs, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTIs, nonnucleoside RTIs; PI, protease inhibito; 1994 CDC class, the 1994 CDC classification system, based on symptoms.

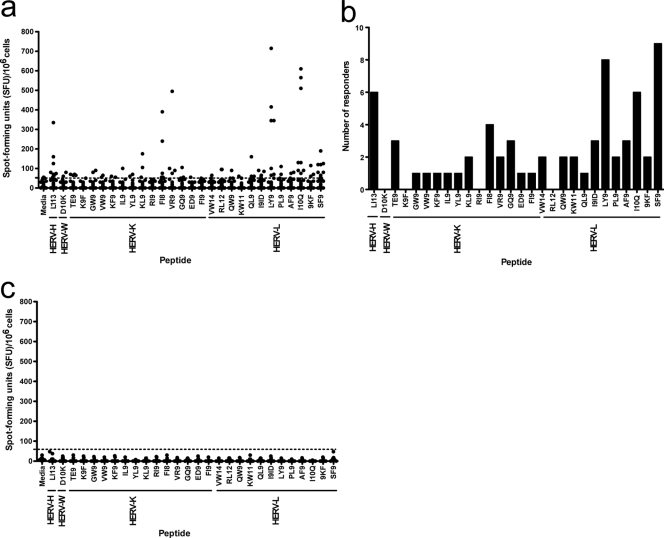

Twenty-six patients had at least one HERV-specific T cell response. The breadth and magnitude of the responses varied (Fig. 1a). While some HERV peptides failed to elicit any response, most of the peptides stimulated a response in one or more subjects (Fig. 1b). No anti-HERV T cell responses were observed for 10 healthy HIV-1-uninfected controls (median age, 46 years; interquartile range [IQR], 32 to 51 years) (Fig. 1c). Multiple full-length open reading frames for all HERV-K proteins have been found in the human genome (2). Therefore, we hypothesized that many of the HERV-specific T cell responses would match epitopes from the HERV-K family. To our surprise, HERV-L- and HERV-H-specific epitopes elicited high-magnitude T cell responses in many subjects (Fig. 1a and b).

Fig. 1.

HERV-specific T cell responses in vertically HIV-1-infected subjects. (a) The x axis represents peptides specific for HERV-H, HERV-W, HERV-K, and HERV-L families. The y axis indicates IFN-γ spot-forming units (SFU)/106 PBMC. The black circles represent each patient. The dotted horizontal line indicates the cutoff point, which is >50 SFU and two times higher than the background. All values are shown after background subtraction. (b) Distribution of HERV responses among subjects. (c) HERV-specific T cell responses in 10 healthy controls.

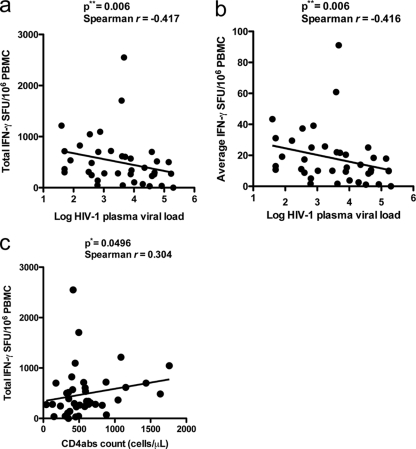

We also examined whether anti-HERV T cell responses were inversely related to the HIV-1 plasma viral load. There was a significant negative correlation between total HERV-specific T cell responses and HIV-1 plasma viral load (P = 0.006, Spearman r = −0.417) (Fig. 2a). In addition, a significant negative correlation was also found when the average combined HERV-specific T cell responses were compared with the HIV-1 plasma viral load (P = 0.006, Spearman r = −0.416) (Fig. 2b). No significant correlation was found when anti-HERV and anti-HIV-1 T cell responses were compared (data not shown), suggesting that these two responses are independent and that within a given peptide set, children with HERV-specific T cell responses do not necessarily mount concomitant HIV-1-specific responses. We also detected a significant direct correlation between the total HERV-specific T cell response and CD4+ T cell count (P = 0.0496, Spearman r = 0.304) (Fig. 2c). CD4+ T cells may influence the quality of the CD8+ T cell response, and we would predict that patients with higher CD4+ T cell levels and greater degrees of immunocompetence would generate robust anti-HERV responses with enhanced functional capacities. This is consistent with our observation of a direct association between the HERV response and the CD4+ T cell count.

Fig. 2.

Inverse correlation between anti-HERV T cell responses and HIV-1 plasma viral load, and absolute CD4+ T cell count (cells/μl). PBMC from 42 vertically HIV-1-infected subjects on combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) were analyzed by ELISPOT assay for HERV responses. The total sum and average of HERV responses (>50 SFU/106 PBMC and two times higher background) had a significant inverse correlation with the HIV-1 plasma viral load. (a) Total sum of HERV responses versus HIV-1 plasma viral load as shown in the figure. (b) Average HERV response versus HIV-1 plasma viral load. (c) Significant direct correlation between total sum of HERV responses versus absolute CD4+ T cell count (CD4abs).

While most perinatal HIV-1 transmission takes place at the time of birth, it is well established that maternal-fetal transmission of HIV-1 can also occur throughout gestation (9, 12, 25). Infection in utero could lead to the induction of immunological tolerance to HIV-1 (17) as well as to any induced HERV products. Our data clearly demonstrate that vertically infected children can mount anti-HERV responses. However, the impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1 replication and HERV expression, and its corresponding influence on the host HERV and HIV-1 response, needs to be further addressed before any protective function can be attributed to HERV-specific responses.

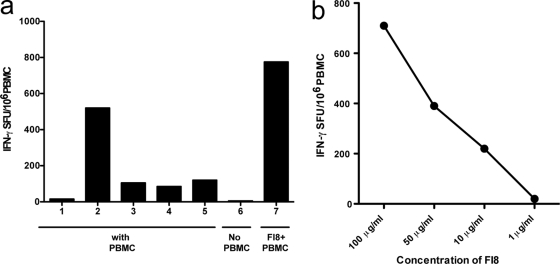

Previous studies have shown that ART can diminish but not fully extinguish HERV RNA expression and, by inference, HERV protein production. This question was approached in a more systematic fashion by performing a longitudinal study of CD8+ T cell responses to an HLA-restricted HERV peptide within a single treatment-experienced patient (S1) initiating potent combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). In order to determine the HLA restriction of the HERV-K reverse transcriptase (RT) FAFTIPAI (FI8) peptide-specific T cell response, we used single-allele B cell transfectants to determine the restriction of the FI8 peptide. Briefly, 104 B cell transfectants were pulsed with peptide for 1 h at 37°C followed by three washes before cells were added to a standard ELISPOT assay with PBMC (23). FI8-pulsed HLA-A*02-positive B cell transfectants elicited a strong IFN-γ response when incubated with PBMC derived from S1, whereas FI8-pulsed HLA-unmatched (HLA-A*02-negative) B cell transfectants elicited only a background response, indicating that the FI8 response was restricted by HLA-A*02 (Fig. 3a). Of note, the HERV FI8 response can also be restricted by HLA-B51 in other individuals (23).

Fig. 3.

HLA restriction and peptide titration. (a) Subject S1's response to peptide HERV-K: FAFTIPAI (FI8) is restricted by the HLA-A02 allele in an ELISPOT-based assay. PBMC were incubated with the following: (bar 1) medium, (2) HLA-A02+ B cells pulsed with FI8 peptide, (3) HLA-A02-B cells pulsed with FI8 peptide, (4) HLA-A02+ unpulsed B cells, (5) HLA-A02− unpulsed B cells (6) all of the above conditions using B cells alone, without PBMC, (7) HERV-K FI8 peptide with PBMC. (b) HERV-K FI8 peptide titration for patient P1 shows that FI8 is able to elicit a T cell response up to 10 μg/ml.

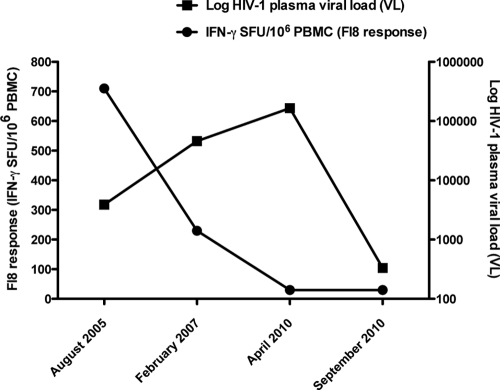

The FI8-specific T cell response was dose dependent, as the strength of the response (in SFU/million PBMC) diminished with decreasing concentrations of the FI8 peptide (Fig. 3b). The response to the FI8 peptide was highest in the setting of detectable but low HIV-1 viremia (3,900 copies/ml) and stable CD4+ T cell count (674 cells/mm3) in August 2005 and, interestingly, declined as the HIV-1 viral load peaked at 165,223 copies/ml in April 2010, before the patient began a more effective suppressive cART regimen. The FI8 response remained low in September 2010 in the setting of poor immune reconstitution (CD4+ T cell count, 267 cells/mm3) and an HIV-1 viral load that had begun to rebound to 331 copies/ml after a brief period of transiently suppressive cART (Fig. 4). This trend is in agreement with our recent published data on untreated adults with chronic HIV-1 infection, showing that untreated HIV-1-infected individuals with the ability to control viral replication in the absence of treatment (“controllers”) had stronger and broader HERV-specific T cell responses than patients with ART suppression of viral replication (ART-suppressed patients), virologic noncontrollers, immunologic progressors, and uninfected controls (23). In addition, we showed that anti-HERV T cell responses were associated with lower HIV-1 viral loads and higher CD4+ counts in untreated HIV-1-infected adults (23). Our data suggest that anti-HERV T cell responses have the potential to act against HIV-1, but we cannot rule out the possibility that stron- ger HERV responses may simply be a reflection of a more intact immunological status. Recent data from our lab showed that HIV-1-infected subjects with preserved CD4+ T cell counts had no differences in their cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65 T cell responses, while progressors with low CD4+ T cell counts had lower CMV pp65 responses than controllers and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)-suppressed patients (23).

Fig. 4.

Longitudinal analysis of subject S1 revealed that the FI8-specific T cell response diminished at peak HIV-1 plasma viral load (April 2010) and remained low during a period of transiently suppressive ART followed by virologic rebound (September 2010).

Due to current treatment guidelines, most vertically HIV-1-infected individuals in the United States are prescribed ART, albeit with variable levels of adherence. Imperfect adherence leads to fluctuating levels of viremia and eventually leads to drug resistance and treatment failure. We identified one such subject (S1) with a history of poor adherence to ART and high-grade viremia who was found to mount an HLA-restricted response to a particular HERV-K RT peptide, FI8. The kinetics of this patient's HERV response were consistent with our cross-sectional data demonstrating that individuals who lack strong HERV responses have high HIV-1 viral loads and low CD4+ T cell counts. Since older vertically infected cohorts like the one studied here do not typically include antiretroviral-naïve subjects, we were able to examine HERV responses only among treatment-experienced patients. We were therefore surprised to find a significant inverse relationship between the HERV response magnitude and clinical measures of HIV-1 disease progression despite the heterogeneity in our subjects' ART regimens and levels of adherence.

While HIV-1 undergoes an intrinsically high degree of mutation and diversification during the course of infection, HERV proteins expressed on the surface of HIV-1-infected cells remain conserved. Since anti-HERV-specific cytotoxic T cells have the potential to target any HIV-1-infected cell expressing these endogenous retroviral antigens irrespective of HIV-1 sequence variation, they may serve as excellent therapeutic or preventive vaccine candidates.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a Pfizer-sponsored research agreement, NIH/NIAID grants RO1 AI087145, K24AI069994, AI76059, and AI84113, the CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS; grant 1 R24 AI067039-1), UCSF Gladstone Institute of Virology & Immunology Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (P30 AI027763), and the Fogarty International Center (grant D43 TW00003). This work was also supported in part by the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1 RR024131), the American Foundation for AIDS Research (106710-40-RGRL), and the Ragon Institute, Boston, MA.

We thank Lewis Lanier (UCSF) for providing single-HLA allele transfectant B cells used for HLA restriction experiments and Neil Sheppard, Peter Loudon, and James Merson (Pfizer, Inc.) for helpful discussions.

R.B.J., M.A.O., and D.F.N. are listed as inventors on a patent application related to this work.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 August 2011.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. An D. S., Xie Y., Chen I. S. 2001. Envelope gene of the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-W encodes a functional retrovirus envelope. J. Virol. 75:88–3489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbulescu M., et al. 1999. Many human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) proviruses are unique to humans. Curr. Biol. 9:861–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benit L., Lallemand J. B., Casella J. F., Philippe H., Heidmann T. 1999. ERV-L elements: a family of endogenous retrovirus-like elements active throughout the evolution of mammals. J. Virol. 73:01–3308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boller K., et al. 1993. Evidence that HERV-K is the endogenous retrovirus sequence that codes for the human teratocarcinoma-derived retrovirus HTDV. Virology 196:9–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Connor E. M., et al. 1994. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 331:1173–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Contreras-Galindo R., Kaplan M. H., Markovitz D. M., Lorenzo E., Yamamura Y. 2006. Detection of HERV-K(HML-2) viral RNA in plasma of HIV type 1-infected individuals. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 22:979–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Contreras-Galindo R., Lopez P., Velez R., Yamamura Y. 2007. HIV-1 infection increases the expression of human endogenous retroviruses type K (HERV-K) in vitro. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 23:6–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Parseval N., Casella J., Gressin L., Heidmann T. 2001. Characterization of the three HERV-H proviruses with an open envelope reading frame encompassing the immunosuppressive domain and evolutionary history in primates. Virology 279:8–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. di Maria H., et al. 1986. Transplacental transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Lancet ii:5–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garrison K. E., et al. 2007. T cell responses to human endogenous retroviruses in HIV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 3:e165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laderoute M. P., et al. 2007. The replicative activity of human endogenous retrovirus K102 (HERV-K102) with HIV viremia. AIDS 21:2417–2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lewis S. H., Reynolds-Kohler C., Fox H. E., Nelson J. A. 1990. HIV-1 in trophoblastic and villous Hofbauer cells, and haematological precursors in eight-week fetuses. Lancet 335:5–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lower R., et al. 1993. Identification of human endogenous retroviruses with complex mRNA expression and particle formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:80–4484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magder L. S., et al. 2005. Risk factors for in utero and intrapartum transmission of HIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 38:87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mayer J., et al. 2004. Human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K(HML-2) proviruses with Rec protein coding capacity and transcriptional activity. Virology 322:190–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mayer J., Meese E., Mueller-Lantzsch N. 1997. Chromosomal assignment of human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) env open reading frames. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 79:7–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCune J. M. 1991. HIV-1: the infective process in vivo. Cell 64:1–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McIntosh K., et al. 1996. Age- and time-related changes in extracellular viral load in children vertically infected by human immunodeficiency virus. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 15:87–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mofenson L. M., et al. 1997. The relationship between serum human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) RNA level, CD4 lymphocyte percent, and long-term mortality risk in HIV-1-infected children. J. Infect. Dis. 175:29–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelson P. N. 1995. Retroviruses in rheumatic diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 54:1–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nelson P. N., et al. 1999. Molecular investigations implicate human endogenous retroviruses as mediators of anti-retroviral antibodies in autoimmune rheumatic disease. Immunol. Invest. 28:7–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rich K. C., et al. 2000. Maternal and infant factors predicting disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected infants. Pediatrics 105:e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. SenGupta D., et al. 2011. Strong human endogenous retrovirus-specific T cell responses are associated with control of HIV-1 in chronic infection. J. Virol. 85:6977–6985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sharp E. R., et al. 2005. Higher frequency of HIV-1-specific T cell immune responses in African American children vertically infected with HIV-1. J. Infect. Dis. 192:1772–1780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sprecher S., Soumenkoff G., Puissant F., Degueldre M. 1986. Vertical transmission of HIV in 15-week fetus. Lancet ii:288–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sugimoto J., Schust D. J. 2009. Review: human endogenous retroviruses and the placenta. Reprod. Sci. 16:23–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wade N. A., et al. 2004. Decline in perinatal HIV transmission in New York State (1997–2000). J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 36:1075–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]