Abstract

We have evaluated the in vitro activity of anidulafungin (AFG) against 31 strains of Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto by using broth microdilution, disk diffusion, and minimal fungicidal concentration (MFC) determination procedures. The two first methods showed a high level of activity of the drug, while MFCs were 1 to 5 dilutions higher than their corresponding MICs. To assess if MICs were predictive of in vivo outcomes, six strains representing different AFG MICs (0.12 to 2 μg/ml) were tested in a murine model of disseminated infection treated with different doses of the drug (1, 5, or 10 mg/kg of body weight). AFG was able to prolong the survival of mice infected with all the strains tested but was able to reduce the tissue burden of those mice infected only with the strains that showed the lowest MIC (0.12 μg/ml).

INTRODUCTION

Candida parapsilosis is one of the most common causes of invasive candidiasis worldwide (14, 20, 21). Lipid formulations of amphotericin B, caspofungin (CSP), or voriconazole (VRC) have been recommended as first-line empirical treatment of invasive candidiasis in neutropenic patients, with fluconazole and itraconazole being considered alternatives (11). However, recent studies suggested that the use of azoles in the treatment of Candida infections may contribute to an increase in the clinical resistance of C. parapsilosis to these antifungal drugs (17). Since C. parapsilosis isolates are susceptible to the echinocandins (17), these drugs have been suggested to be a good therapeutic choice for C. parapsilosis infections, preventing an increase in azole resistance (17). Echinocandin MICs for C. parapsilosis are generally higher than those for other Candida species (2, 4, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16), but the clinical significance of the in vitro data is unknown (16, 20). Anidulafungin (AFG), the most recently approved echinocandin, has shown high-level in vitro and in vivo activities against Candida spp. and is recommended for the treatment of esophageal candidiasis, candidemia, and other invasive Candida infections (15). Recently, clinical breakpoints for AFG have been established against several Candida spp., which can be very useful for the detection of possible emerging resistance, although in the case of C. parapsilosis, they are based on a small number of clinical cases (n = 17) (15). Animal studies can play an important role in obtaining a better understanding of the in vitro-in vivo correlation, allowing a significant increase in the number of strains tested under controlled in vivo conditions. In our study, we have evaluated the in vitro activity of AFG and its in vivo efficacy in the treatment of invasive murine infection by C. parapsilosis, testing clinical isolates with different MICs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The in vitro antifungal susceptibilities of 31 clinical strains of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto to AFG were identified by comparing their internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences with those of reference strains. All isolates were of clinical origin and from patients who, according our files, had not previously been treated with any echinocandin. Their susceptibility to AFG was evaluated in duplicate by determinations of the MICs (in μg/ml), their inhibition zone diameters (IZDs) (in mm), and the minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFCs) (in μg/ml). MICs were determined by a broth microdilution method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines for yeasts (5). IZDs were determined according to CLSI guidelines for disk diffusion testing of yeasts (6). C. parapsilosis strain ATCC 22019 was used as a quality control (QC). The MFC was determined by subculturing 20 μl of each well that showed complete inhibition (100% inhibition or an optically clear well) relative to the last positive well and the growth control onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates. The plates were incubated at 35°C until growth was seen in the control subculture. The MFC was considered the lowest drug concentration at which approximately 99.9% of the original inoculum was killed (7).

For murine studies, we chose six of those strains tested in vitro. There were two strains, FMR 11574 and FMR 10296, with MICs of 0.12 μg/ml; two strains, FMR 10292 and FMR 9544, with MICs of 1 μg/ml; and two strains, FMR 11562 and FMR 10293, with MICs of 2 μg/ml. The fungi were stored at −80°C, and they were subcultured on SDA at 35°C prior to testing. For animal inoculation, cultures on SDA were suspended in sterile saline. The resulting suspensions were adjusted to the desired inoculum based on hemocytometer counts and by serial plating onto SDA to confirm viability.

Male OF1 mice weighing 30 g (Charles River, Criffa S.A., Barcelona, Spain) were used in this study. Animals were housed under standard conditions, and the care procedures were supervised and approved by the Universitat Rovira i Virgili Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee. Mice were immunosuppressed 1 day prior to infection by the administration of a single dose of 200 mg of cyclophosphamide per kg of body weight intraperitoneally (i.p.) plus a single dose of 150 mg of 5-fluorouracil per kg intravenously (i.v.) (9). Two different inocula were used in this study. For survival studies, the mice were challenged with 4 × 107 CFU in 0.2 ml of sterile saline injected into the lateral tail vein. Preliminary experiments testing several strains demonstrated that with this inoculum, the mortality rates were approximately 90% within 10 days after infection, allowing the animals to receive at least 5 days of treatment (data not shown). In tissue burden studies, the mice were inoculated with 4 × 106 CFU in 0.2 ml of sterile saline injected into the lateral tail vein. This inoculum was chosen in order to obtain a significant fungal load in organs but not cause the animals to die. In that way, animals could receive the entire treatment regimen and be compared with controls.

We tested AFG (Ecalta; Pfizer Ltd., Sandwich, Kent, United Kingdom) administered at 1, 5, or 10 mg/kg of body weight i.p. once a day (QD). To prevent bacterial infection, all animals received ceftazidime at 5 mg/kg day subcutaneously. All treatments began 24 h after challenge and lasted for 7 days. The efficacy of AFG was evaluated by prolongation of survival, tissue burden reduction, histopathological studies, and determination of mannan antigenemia and (1→3)-β-d-glucan serum levels.

For the survival studies, groups of 10 mice were randomly established for each strain and treatment and checked daily for 30 days after challenge. Controls received no treatment. For the tissue burden studies, groups of 10 mice were also established, and the animals were sacrificed on day 7 postinfection in order to compare the results with those of untreated controls. Kidneys, liver, and spleen were aseptically removed, and approximately half of each organ was weighed and homogenized in 1 ml of sterile saline. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the homogenates were plated onto SDA and incubated for 24 h at 35°C, and the CFU/g of tissue was calculated. For the histopathology study, half of each organ was fixed with 10% buffered formalin. Samples were dehydrated, paraffin embedded, and sliced into 2-μm sections, which were then stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain, or Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) and examined in a blinded fashion by light microscopy. Additionally, an average of 1.0 ml of blood from each mouse infected with C. parapsilosis strain FMR 11574 and treated with AFG at 1, 5, or 10 mg/kg was collected on day 7 postinfection for determinations of the drug levels in serum by bioassay 4 h after drug administration (3), and the mannan and (1→3)-β-d-glucan serum levels were determined by using Platelia Candida antigen (Ag) (Bio-Rad, Marnes la Coquette, France) and a Fungitell kit (Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA), respectively. Likewise, the remaining kidney was also aseptically removed to determine drug concentrations in this organ by a bioassay.

The mean survival times were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared among groups by using the log rank test. Colony counts from tissue burden studies were analyzed by using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was carried out to determine the normal distribution of (1→3)-β-d-glucan, mannan serum levels, and bioassay data so that they could be analyzed by using the t test.

RESULTS

The in vitro susceptibility results showed MICs of ≤2 μg/ml and IZDs of ≥10 mm for AFG against all strains of C. parapsilosis. The IZD range was 10 to 23 mm. For 84% of the strains tested, the difference between MFC and MIC values were within 3 dilutions, and the other strains (16%) were 4 to 5 dilutions higher than the corresponding MICs (Table 1). The results for the reference quality control strain (C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019) were within the range established by the CLSI (5).

Table 1.

In vitro activities of AFG against 31 isolates of C. parapsilosis

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) | IZD (mm) | MFC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMR 9544 | 1 | 12 | 4 |

| FMR 9613 | 1 | 13 | 8 |

| FMR 9609 | 0.5 | 15 | 8 |

| FMR 9612 | 1 | 15 | 4 |

| FMR 9611 | 0.5 | 15 | 4 |

| FMR 9608 | 1 | 13 | 4 |

| FMR 9614 | 0.5 | 15 | 4 |

| FMR 9615 | 1 | 13 | 4 |

| FMR 9610 | 0.25 | 20 | 4 |

| FMR 9601 | 2 | 10 | 8 |

| FMR 10291 | 1 | 14 | 4 |

| FMR 10292 | 1 | 17 | 4 |

| FMR 11566 | 0.5 | 15 | 4 |

| FMR 11573 | 0.5 | 11 | 4 |

| FMR 11571 | 2 | 14 | 4 |

| FMR 10288 | 1 | 16 | 4 |

| FMR 10289 | 1 | 15 | 8 |

| FMR 10296 | 0.12 | 22 | 4 |

| FMR 11563 | 0.25 | 20 | 4 |

| FMR 11769 | 0.25 | 17 | 2 |

| FMR 10304 | 0.5 | 22 | 4 |

| FMR 11572 | 0.5 | 15 | 2 |

| FMR 10301 | 0.5 | 18 | 4 |

| FMR 10293 | 2 | 12 | 8 |

| FMR 10297 | 0.5 | 14 | 4 |

| FMR 10290 | 0.5 | 13 | 4 |

| FMR 11565 | 2 | 11 | 4 |

| FMR 11574 | 0.12 | 23 | 4 |

| FMR 11562 | 2 | 16 | 4 |

| FMR 11564 | 2 | 11 | 4 |

| FMR 10302 | 1 | 16 | 4 |

| ATCC 22019 | 1 | 15 | 2 |

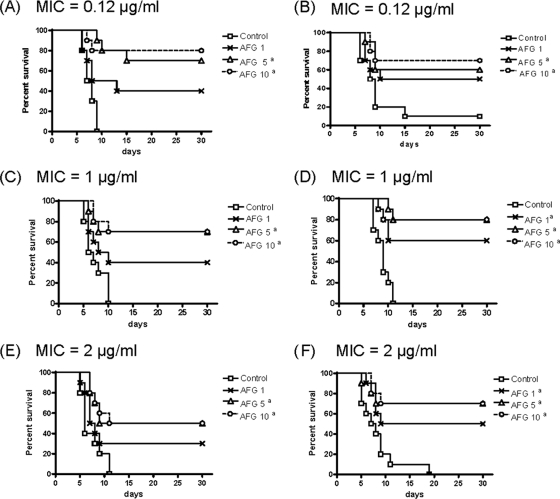

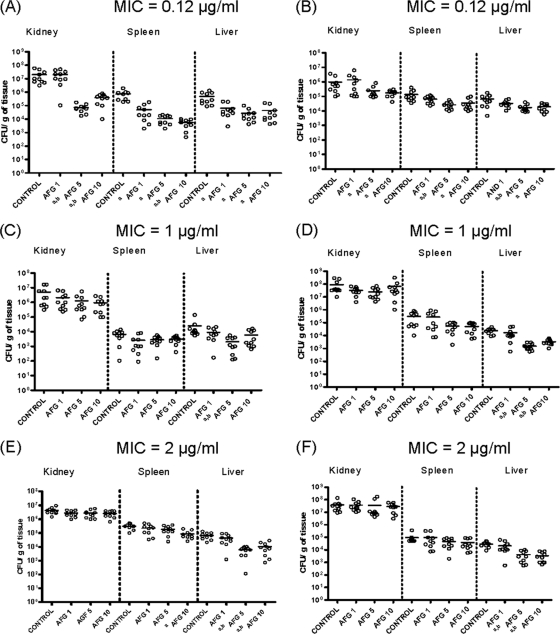

The results of survival studies are shown in Fig. 1. AFG at 5 or 10 mg/kg for all strains and AFG at 1 mg/kg for two strains (one showing an MIC of 1 μg/ml and another one showing an MIC of 2 μg/ml) significantly prolonged survival in comparison with the control group. For the two strains with the lowest MICs (0.12 μg/ml), AFG at 5 or 10 mg/kg reduced the fungal load in the three organs tested, while for the other strains, those dosages reduced the fungal load only in liver, in almost all cases (strains FMR 10292, FMR 9544, FMR 11562, and FMR 11293), and in spleen only occasionally (FMR 11562). AFG at 1 mg/kg reduced the fungal load only in spleen and in liver for strain FMR 11574 (MIC = 0.12 μg/ml). However, for the other strain with an AFG MIC of 0.12 μg/ml (FMR 10296), AFG at 1 mg/kg was not able to significantly reduce CFU in spleen and liver. For strain FMR 10296, the fungal burden in the kidneys of untreated mice was 1 log lower than that of the other strain (FMR 11574), despite it having the same MIC, suggesting a lower virulence of this strain. The comparison of the kidney CFU counts also showed a similar pattern between strains with the same susceptibility to AFG (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative mortality of mice infected with C. parapsilosis FMR 11574 (A), FMR 10296 (B), FMR 10292 (C), FMR 9544 (D), FMR 11562 (E), and FMR 10293 (F). AFG 1, anidulafungin at 1 mg/kg QD; AFG 5, anidulafungin at 5 mg/kg QD; AFG 10, anidulafungin at 10 mg/kg QD. a, P < 0.05 versus the control.

Fig. 2.

Effects of AFG on colony counts of C. parapsilosis FMR 11574 (A), FMR 10296 (B), FMR 10292 (C), FMR 9544 (D), FMR 11562 (E), and FMR 10293 (F) in kidneys, liver, and spleen of neutropenic mice. AFG 1, anidulafungin at 1 mg/kg QD; AFG 5, anidulafungin at 5 mg/kg QD; AFG 10, anidulafungin at 10 mg/kg QD. a, P < 0.05 versus control group; b, P < 0.05 versus AFG at 1 mg/kg.

Table 2 shows the AFG levels in serum and kidney. At day 7 of treatment, for all doses administered, antifungal levels in serum and kidneys were above the corresponding MIC values for the strains tested and increased with dose escalation.

Table 2.

Drug levels in serum and kidneys measured by bioassay on day 7 of therapy and 4 h after last dose

| Dose of AFG (mg/kg) | Mean drug concn ± SD |

|

|---|---|---|

| Serum (μg/ml) | Kidney (μg/g) | |

| 1 | 2.92 ± 1.23 | 2.06 ± 1.06 |

| 5 | 10.85 ± 1.6a | 8.5 ± 2.34a |

| 10 | 13.66 ± 1.15a,b | 13.84 ± 1.46a,b |

P < 0.05 versus AFG at 1 mg/kg QD.

P < 0.05 versus AFG at 5 mg/kg QD.

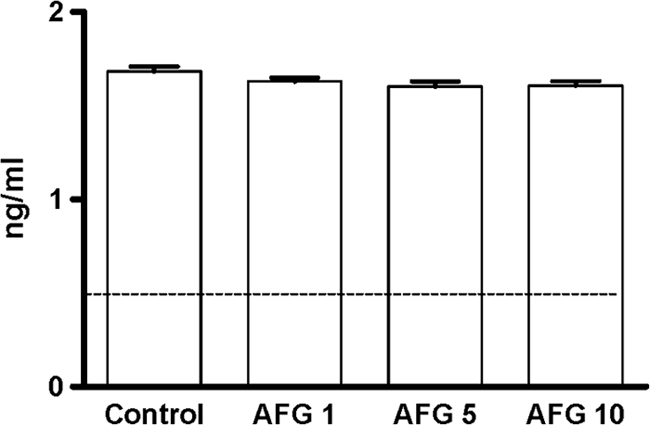

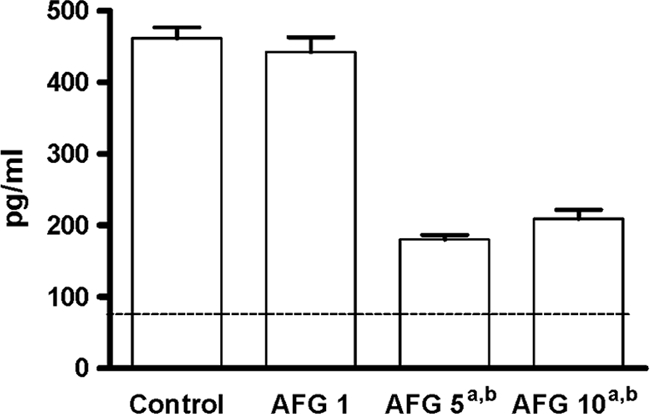

No dose of AFG at the end of the therapy was able to reduce the mannan serum concentrations in comparison with the untreated group (Fig. 3). At day 7 of treatment, in all the cases, the (1→3)-β-d-glucan serum levels were positive (>80 pg/ml) (18), although those levels were significantly lower in animals treated with AFG at 5 or 10 mg/kg than in control animals and in those treated with AFG at 1 mg/kg (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Mannan antigen serum levels in mice infected with C. parapsilosis measured at day 7 (final treatment) (n = 5 animals per group). AFG 1, anidulafungin at 1 mg/kg; AFG 5, anidulafungin at 5 mg/kg; AFG 10, anidulafungin at 10 mg/kg. The horizontal line indicates the cutoff for positivity (0.5 ng/ml).

Fig. 4.

(1→3)-β-d-Glucan serum concentrations in mice infected with C. parapsilosis measured at day 7 (final treatment) (n = 5 animals per group). AFG 1, anidulafungin at 1 mg/kg; AFG 5, anidulafungin at 5 mg/kg; AFG 10, anidulafungin at 10 mg/kg QD. a, P < 0.05 versus control; b, P < 0.05 versus AFG at 1 mg/kg. The horizontal line indicates the cutoff for positivity (80 pg/ml).

The histological study showed abundant fungal cells and signs of necrosis and an inflammatory response in the kidneys of untreated controls and of mice treated with any dose of AFG. Livers of controls and of mice of all treatment groups showed fungal invasion, but there were no signs of necrosis or an inflammatory response. There were neither tissue lesions nor fungal invasion in spleens of controls or mice treated with AFG.

DISCUSSION

Although some clinical trials have demonstrated the therapeutic efficacy of echinocandins in invasive candidiasis, including that caused by C. parapsilosis (16, 19), some controversy exists about the usefulness of echinocandins in the treatment of disseminated infections caused by that fungus. Currently, echinocandins are not recommended for the treatment of C. parapsilosis fungemia because of the high MICs that these drugs show for such species in comparison to other species of Candida (11).

On the basis of the IZD-suggested breakpoints for CSP, i.e., susceptible at ≥13 mm, intermediate at 11 to 12 mm, and resistant at ≤10 mm (15), in general, our study showed a good correlation between the results obtained with the microdilution method and those obtained with the disk diffusion method. However, we did not find any correlation with the IZD breakpoints suggested for micafungin (MFG), which are ≥16 mm, 14 to 15 mm, and ≤13 mm, respectively (15). Since there are no IZD susceptibility breakpoints for AFG against C. parapsilosis, a more accurate comparison between MICs and IZDs for that antifungal and that species was not possible.

Contrary to the results obtained in another experimental study on the efficacy of echinocandins in disseminated infections by C. parapsilosis (2), we have obtained a correlation between the MICs and the in vivo outcome that agrees with the results of the clinical trials, which showed 100% success in the treatment of infections by C. parapsilosis strains with AFG MIC values of 0.25 μg/ml, in comparison with success rates of 87.5 to 90% for infections caused by strains with MICs of ≥0.5 μg/ml (15). In a study reported previously by Barchiesi et al. (2), using a murine model similar to ours, CSP at 1 and 5 mg/kg was effective in reducing the kidney fungal load in mice infected with a C. parapsilosis strain with a CSP MIC of 4 μg/ml, whereas only the 5-mg/kg dosage was effective in mice infected with those strains with CSP MICs of 0.5 or 1.0 μg/ml (2). In our study, the efficacy of AFG was poor in reducing the fungal burden in organs of mice infected with the strains with high MICs, although the drug improved the survival of mice against all the strains tested. AFG was more effective in reducing the fungal load in the organs of animals challenged with C. parapsilosis strains with low AFG MICs (0.12 μg/ml).

In agreement with pharmacodynamic studies of echinocandins (1), our results on tissue burden, histopathology, and mannan and (1→3)-β-d-glucan serum levels showed that for the treatment of infection with strains that have MICs of 1 or 2 μg/ml, higher doses of AFG were required for improving survival.

Although AFG in general worked well against all the strains of C. parapsilosis tested, this study demonstrated that the response to treatment is largely strain dependent and clearly related to in vitro activity. It was noted previously that more than 90% of clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis are encompassed by a breakpoint of ≤2 μg/ml (15). It should also be noted that we did not test the efficacy of other antifungal drugs as active controls, which would have allowed a better assessment of the activity of AFG.

On the other hand, we have demonstrated that, at least in experimental studies, there are still some important differences among those strains with MICs of ≤2 μg/ml, and it would be interesting to explore them in future studies. In our study, MICs of 0.12 μg/ml were clearly the most predictive of in vivo success, while we did not find any differences between MICs of 1 and 2 μg/ml. It would also be interesting in future studies to refine these results, carrying out further animal studies with strains with other AFG MICs, e.g., intermediate between 0.12 and 1 μg/ml and ≥2 μg/ml, in order to assess more accurately which MICs can predict a risk of clinical failure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The current work has been funded in part by project GIC07 123-IT-222 (Departamento de Educación, Universidades e Investigación, Gobierno Vasco).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andes D., et al. 2010. In vivo comparison of the pharmacodynamic targets for echinocandin drugs against Candida species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2497–2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barchiesi F., et al. 2006. Effects of caspofungin against Candida guilliermondii and Candida parapsilosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2719–2727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calvo E., Pastor F. J., Mayayo E., Salas V., Guarro J. 2010. In vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of anidulafungin in murine infections by Aspergillus flavus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1290–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cantón E., Espinel-Ingroff A., Pemán J., del Castillo L. 2010. In vitro fungicidal activities of echinocandins against Candida metapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. parapsilosis evaluated by time-kill studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2194–2197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard, 3rd ed Document M27-A3 CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Method for antifungal disk diffusion susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved guideline. Document M44-A2 CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 7. Espinel-Ingroff 1998. Comparison of in vitro activities of the new triazole SCH 56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2950–2956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghannoum M. A., et al. 2009. Differential in vitro activity of anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin against Candida parapsilosis isolates recovered from a burn unit. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:274–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graybill J. R., Bocanegra R., Najvar L. K., Loebenberg D., Luther M. F. 1998. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and azole antifungal therapy in murine aspergillosis: role of immune suppression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2467–2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuti E. L., Kuti J. L. 2010. Pharmacokinetics, antifungal activity and clinical efficacy of anidulafungin in the treatment of fungal infections. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 6:1287–1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pappas P. G., et al. 2009. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infections Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:503–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pfaller M. A., et al. 2008. In vitro susceptibility of invasive isolates of Candida spp. to anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin: six years of global surveillance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:150–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pfaller M. A., et al. 2005. In vitro activities of anidulafungin against more than 2,500 clinical isolates of Candida spp., including 315 isolates resistant to fluconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5425–5427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pfaller M. A., Diekema D. J. 2007. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20:133–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pfaller M. A., et al. 2011. Clinical breakpoints for the echinocandins and Candida revisited: integration of molecular, clinical, and microbiological data to arrive at species-specific interpretative criteria. Drug Resist. Updat. 14:164–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pfaller M. A., et al. 2005. Effectiveness of anidulafungin in eradicating Candida species in invasive candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4795–4797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pfaller M. A., Moet G. J., Messer S. A., Jones R. N., Castanheira M. 2011. Candida bloodstream infections: comparison of species distributions and antifungal resistance patterns in community-onset and nosocomial isolates in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 2008-2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:561–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pickering J. W., Sant H. W., Bowles C. A. P., Roberts W. L., Woods G. L. 2005. Evaluation of a (1→3)-β-D-glucan assay for diagnosis of invasive fungal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5957–5962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reboli A. C., et al. 2007. Anidulafungin versus fluconazole for invasive candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:2472–2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trofa D., Gácser A., Nosanchuk J. D. 2008. Candida parapsilosis, an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:606–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Asbeck E. C., Clemons K. V., Stevens D. A. 2009. Candida parapsilosis: a review of its epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical aspects, typing and antimicrobial susceptibility. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35:283–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]