Abstract

Background:

The subject of Biomedical Ethics has become recognized as an essential integral component in the undergraduate curriculum of medical students.

Objectives:

(1) To review the current Biomedical Ethics Course offered at the College of Medicine, King Saud bin Abdul-Aziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS). (2) To explore the perception of medical students on the different components of the course.

Materials and Methods:

The medical students were requested to participate in the study at the end of the course by filling in a pre-designed questionnaire. A qualitative approach was used also to examine their perceptions about certain components of the course.

Results:

Forty-one medical students participated in this study. All students expressed their strong agreement on the importance of their learning biomedical ethics. Their views about the role of Biomedical Ethics were also considered. These include professional development, assessment of ethical competencies, and the timing of the teaching of ethics.

Conclusion:

The students provided valuable comments that were supported by the literature reviews. Medical Students’ views of the teaching of the various components of biomedical ethics are important and should be sought in the planning of a curriculum.

Keywords: Bioethics, bioethics curriculum, bioethics learning, bioethics teaching, professional development

INTRODUCTION

Although the importance of medical ethics was recognized a longtime ago, only within the last three decades has it emerged as a priority in formal medical education.[1] This could be the result of increased public pressure, advances in diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and publicity of medical errors. Since 1990, courses in medical ethics have become an integral part of the core curriculum in most medical schools in western countries[2] as a response to the recommendations of General Medical Council (GMC) in tomorrow's doctors’ document.[3]

However, the formal inclusion of medical ethics in the medical curriculum has resulted in the emergence of a variety of curricula on ethics with diverse goals, using varying methods.[2,4,5] Thus, the provision and methods of assessment of ethics vary greatly among undergraduate medical programs even within the same country.[2] Consequently, undergraduate medical students continue to have little confidence in their ability to address ethical issues and perceive a need for additional support from their clinical teachers.[6] In the west, serious shortcomings in many areas of the literature on medical ethics education have been reported. These include those that deal with teaching methods and outcomes for students.[7]

Many medical schools have been recently established in Saudi Arabia, and it has been learned that medical ethics is taught in most if not all our medical schools. However, the authors have not found any literature published locally on this important subject.

Thus, this paper reports our experience in running and evaluating an undergraduate medical ethics course, particularly in relation to students’ experience of their first exposure to the teaching of medical ethics. The aim is to stimulate discussion on how to improve the teaching of medical ethics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

The medical school at Kind Saud bin Abdul-Aziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS) offers problem-based, community-oriented and integrated undergraduate curriculum. Medical ethics is taught in a 4-week course in the first year and multiple sessions are integrated longitudinally within different blocks of the curriculum.

By the end of this course, the following objectives are expected to have been achieved by students. The students should be able to:

Describe the major principles of medical ethics.

Provide definitions and give supporting evidence on the importance of autonomy, confidentiality, adequate information and building of trust.

Describe ethical and legal issues related to medical research on patients

Describe the ethical boundaries of genetic therapy.

Describe the ethical issues related to the rights of individuals including human rights to quality healthcare and an equitable distribution of resources.

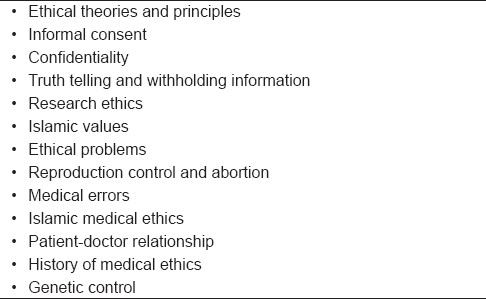

The contents of the course are shown in Table 1. The content is in response to three problems. Its objectives are as follows: definition of ethics, identification of the principles of ethics, and patients’ right, ethical principles of blood transfusion, limitations of obtaining consent, breaking bad news, terminal illness and care of dying persons. Each PBL session was conducted over two sessions using the “seven” jumps of BPL session.

Table 1.

The contents of the course

Assessment

Students were assessed on their participation in PBL tutorials, attendance, individual assignments, midterm examinations and final examination. The examinations included short answer questions (SAQ) and to some matching questions. In SAQs, students were given a principle or ethical problems and were asked to identify the problems, outline how they would deal with them.

Students were requested to write an individual report on a real ethical problem encountered either by them or their relatives or which has aroused the attention of the media. The report was to include a description of the problem and an explanation of the ethical dilemma and how it could be resolved. This assignment was to encourage the student to reflect on what had been learned and its application to the real world.

Methods

Undergraduate medical students were requested to participate in this study by filling a self- administered questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of three main sections. The first included rating of students’ perception of the importance and their need for the teaching of ethics, relevance of contents, whether the teaching of ethics simply depended on common sense or required formal teaching, the timing of teaching ethics in the curriculum and their opinion on the assessment to be used. Some of these questions had been used in a previous study.[8]

The second section included the rating of the three problems used for the PBL sessions in terms of what was learned from the problem, their relevance and whether they were simulating. Students were asked to answer the questions in these two sections by rating their opinions on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The third section consisted of open-ended questions meant to elicit students’ opinions on the benefits derived from the course, recommendation for future opportunities of teaching ethics, the areas of ethics most needed in teaching and what contribution the teaching of ethics could make to their professional development.

A qualitative approach was used to examine students’ perception of the ethics course. Their opinions were sought on the importance of the topic, contents of the course, timing, teaching methods and assessment.

RESULTS

A total number of forty-one medical students participated in the study. Students expressed strong agreement on the importance and their need to learn the principles of medical ethics for their future professional practice. To a lesser extent, they thought that the contents of the course were relevant to their culture and to themselves. They disagreed with the view that medical ethics was just common sense. They couldn’t decide whether the assessment methods used in the course were appropriate or not. Details of their responses are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Students’ evaluation of different components of the course

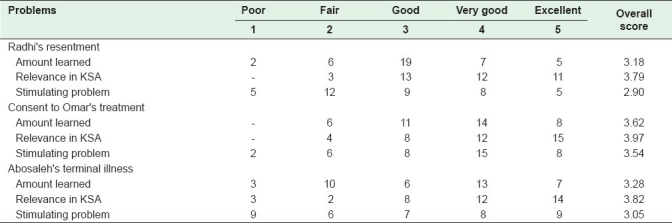

Students’ evaluation of the three problems used in the problem-based learning sessions is shown in Table 3. Students felt that though all three problems were relevant to the culture, they were not very stimulating.

Table 3.

Students’ evaluation of the three problems used in the problem-based sessions

Open-ended questions

What you have benefitted from this course?

The majority of students felt the course was beneficial. The following quotations are examples of students’ perception of benefits:

“I learned something that I would not have known without this course.”

“I learned more about principles of medical ethics.”

“I learned something on how to deal with patients in specific situations.”

“In general, I learned a lot about the medical ethics.”

However, one student saw no benefit.

He said, “I did not benefit.”

How do you think biomedical teaching contributed to your development and growth?

In general, students appreciated the value of the teaching of ethics in their development and growth. The following comments illustrate some of their responses:

“As a medical student, I think it is crucial to our future.”

“It improved my skills and awareness.”

“It made me stronger and more valued.”

“It opened our minds to some new situations.”

“Our brains mature as we learn more.”

“In many ways in order to become a successful doctor.”

How should ethical competencies and skills be assessed?

Most responses suggest a combination of at least two methods, such as multiple-choice questions, short essay questions and oral examinations.

Examples of students’ responses included:

“I think it should be a little bit easier because it is too early for us to learn such subjects.”

“Does not depend in memorizing at all. What is most important is to understand and practice it.”

“Only participation and attendance in the lectures.”

“It has to be completely dependent on PBL sessions.”

“The same as we had.”

“MCQ and Practical.”

“Short essay and MCQs are quite good”

One student said: “I do not understand this question.”

Which year of study would be most appropriate for the teaching of biomedical ethics?

Ten students responded with “I don’t know”. But the majority suggested that the teaching of ethics should be done in the last two years of the curriculum (20 responses) while the minority suggested early in the curriculum (4 responses) and three responded that it should taught both in early years as well as later in curriculum.

Examples of students’ responses include:

“The year we start clinicals.”

“First and last year of medicine.”

“Before we go to the hospital.”

“I think it should be twice, the first now and the second in the last year.”

“I think it is ok in our level.”

“Second year and the year before the last year”

Things you liked best about this block?

Students indicated that Problem-based sessions were the most enjoyable activities of the course. They also indicated that the contents were relevant and they liked the teaching of some of the faculty.

Comments include:

“The problems were great.”

“I enjoyed most aspects. Most topics were related to our future life and they were all interesting.”

“The high level of the doctors and teachers.”

“Time, slides.”

“Nothing.”

“Everything was fine for me”

DISCUSSION

In the light of the recent publicity of patient safety and medical errors, it is essential to emphasize the importance of medical ethics as an integral part of our undergraduate education. I have learnt through personal communication that the teaching of ethics is embedded in most of the undergraduate curricula in Saudi Arabia. Unfortunately, no published literature could be found on the subject. “Those involved in the delivery of undergraduate teaching of ethics perhaps need no convincing of its value in the preparation of doctors of tomorrow. But how is the subject viewed by the medical students themselves?”[7] This study showed that our students strongly valued medical ethics. This is in accord with published literature in the west.[7,8] Participating students saw medical ethics as a subject worth studying and understanding, and not just to be worked out through common sense. It is important for the teachers to address this need properly to equip future doctors to deal with ethical dilemmas they are likely to be confronted with in clinical practice. Most of the contents of the course have been recommended in other curricula.[2,9] The majority of participating students agreed that the contents of the course were relevant and in tune with their culture but a significant minority disagreed. This may be due to the fact that students were still not exposed to clinical practice or the result of the failure of faculty to address the subject. This remains to be seen since these findings would be taken into consideration in the current process of review.

The majority of students saw the benefits of the course. The use of open-ended questions to collect qualitative data from students, in our opinion, added more value.

Features of ethical problems usually include uncertainty and diversity of both opinions and moral values. In order to understand and appreciate such issues they should be discussed and debated among medical students.[9–11] Students will have the opportunity to exchange ideas and reflect on these issues if they are presented and discussed as clinical problems in PBL sessions. Case-discussion in small groups will enhance the sensitivity to oral aspects, will demonstrate some of the applications of ethical concepts and will show students some practical difficulties in applying the concepts to certain clinical situations.[9,12,13]

Students have indicated that medical ethics is best taught at a later stage of the curriculum when they have frequent contact with patients. This probably would enable students to reflect on the encountered ethical dilemmas and would promote better application of the ethical concepts. At this stage, the teaching of ethics would have a great impact as students would realize its relevance and would think more deeply of the ethical dilemmas encountered.[7,14]

Generally, assessment should be formative and summative. Techniques for assessment of medical ethics should include the assessment of cognitive aspects of solving ethical problems, as well as the assessment of ethical decisions and values.[15–17]

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all medical students for their participation in this study. Special thanks are extended to Ms. Badryah Fitzpatrick for editing this paper.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

REFERENCES

- 1.Miles SH, Lane LW, Bickle J, Walker RM, Cassel CK. Medical Ethics Education.Coming of Age. Acad Med. 1989;64:705–14. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glodie J. Review of Ethics curricula in Undergraduate Medical Education. Med Educ. 2000;34:108–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Issued by Education Committee of the General Medical Council. London: GMC; 1993. Medical Council. Tomorrow's Doctors. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consensus Statement-Teaching Medical ethics and Law within medical education: A model for the UK core curriculum. J Med Ethics. 1998;24:177–92. doi: 10.1136/jme.24.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bligh J, Mattick K. Undergraduate ethics teaching: Revisiting the consenus statement. Med Educ. 2006;40:329–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordingly L, Hyde C, Peters S, Vernon B, Bundy C. Undergraduate medical students’ exposure to clinical ethics: A challenge to the development of professional behaviours? Med Educ. 2007;41:1202–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston C, Haughton P. Medical students’ perceptions of their ethics teaching. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:418–22. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.018010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts LW, Warner TD, Hammond KA, Geppert CA, Heinrich T. Becoming a Good doctor: Percieved Need for Ethics Training Focused on Practical and Professional Development Topics. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29:301–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.29.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bella H. Islamic Medical Ethics: What and How to teach? In: Brockopp JE, Eich T, editors. Muslim Medical Ethics: From Theory to Practice. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press; 2008. p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker M. Autonomy, problem based learning, and the teaching of medical ethics. J Med Ethics. 1995;21:305–10. doi: 10.1136/jme.21.5.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt HG. Foundations of problem-based learning: Some explanatory notes. Med Educ. 1993;27:422–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1993.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegler M. A legacy of Osler: Teaching Ethics at the Bedside. JAMA. 1978;239:951–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.239.10.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perkins HS, Saathoff BS. Impact of Medical Ethics Counsaltation on Physcians: An Exploratory Study. Am J Med. 1988;85:761–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholas B. Power and the teaching of medical ethics. J Med Ethics. 1999;25:507–13. doi: 10.1136/jme.25.6.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Self DJ, Wolinsky FD, Baldwin DC. The effect of teaching medical ethics on students’ moral reasoning. Acad Med. 1989;64:755–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myser C, Kerridge IH, Mitchel KR. Ethical reasoning and decision-making: Assessing the process. Med Educ. 1995;29:29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckles RE, Meslin EM, Gaffney M, Helft R. Medical ethics education: Where are we.Where should we be going? A review. Acad Med. 2005;80:1143–52. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200512000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]