Abstract

Cerebral vasculature is richly innervated by the α-1 adrenergic receptors similar to that of the peripheral vasculature. However, the functional role of the α-1adrenergic receptors in cerebral blood flow (CBF) regulation is yet to be established. The traditional thinking being that during normotension and normocapnia sympathetic neural activity does not play a significant role in CBF regulation. Reports in the past have stated that catecholamines do not penetrate the blood brain barrier (BBB) and therefore only influence cerebral vessels from outside the BBB and hence, have a limited role in CBF regulation. However, with the advent of dynamic measurement techniques, beat-to-beat CBF assessment can be done during dynamic changes in arterial blood pressure. Several studies in the recent years have reported a functional role of the α-1adrenergic receptors in CBF regulation. This review focuses on the recent developments on the role of the sympathetic nervous system, specifically that of the α-1 adrenergic receptors in CBF regulation.

Keywords: Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors, cerebral autoregulation, cerebral blood flow

Introduction

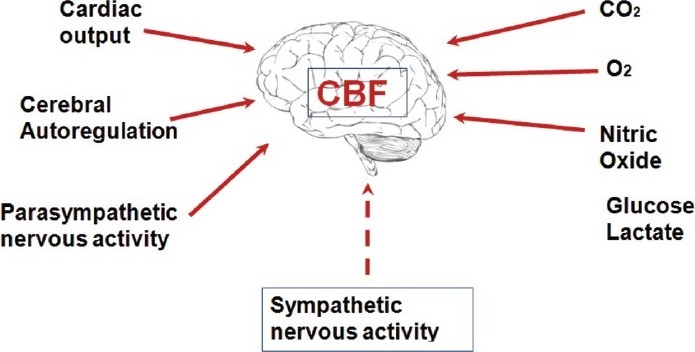

Perivascular nerves have been identified in close proximity to smooth muscle layers in the cerebral vessel[1–3] and the density of innervations of cerebral resistance vessels have been reported to be similar to the mesenteric and/or the femoral arterial beds.[4–5] Astrocytes and vascular cells in association with the perivascular neurons of autonomic origin constitute a functional unit to maintain the cerebral microenvironment homeostasis.[6] Animal studies have identified the cerebral arteries being richly innervated with sympathetic nerve fibers.[7–9] However, the role of autonomic neural control of the cerebral blood flow (CBF) regulation remains controversial.[10–12] CBF is maintained relatively constant despite physiological fluctuations in the cerebral perfusion pressure between ranges of 60 and 150 mmHg by intrinsic myogenic properties of cerebral autoregulation.[13] The current traditional thinking is that in the presence of normocapnia and normotension changes in sympathetic tone appear to have limited effects on CBF.[14,15] Previously, studies have reported that the sympathetic nervous system has an insignificant role in CBF regulation in normal conditions; for example, sectioning of the sympathetic nerves in dogs resulted in no effect on CBF.[15] In addition, no difference in cerebral autoregulation was observed between intact and denervated cerebral hemispheres following unilateral sympathetic denervation.[16] Chronic sympathetic denervation in animal models did not influence cerebral autoregulation.[17] However, activation of the sympathetic nervous system on cerebral vessels is effective during hypertension, hypoxia, hypercapnia, and hemorrhagic states.[18] Furthermore, several investigators have identified a direct effect of sympathoexcitation on CBF in pathophysiological conditions.[19,20] In addition, in primates, the blood flow to the brain through internal carotid and vertebral arteries was reduced by direct stimulation of the cervical and stellate ganglia of the sympathetic nerve fibers of the brain.[21] In humans, a decrease in middle cerebral artery blood velocity (MCA V) was reported during unilateral trigeminal ganglion stimulation.[22] There is also strong evidence that increases in sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction protects cerebral vessels from overperfusion during hypertension. For example, in an animal model of hypertension the breakdown of the blood brain barrier (BBB) in the cerebrum was prevented by electrically induced sympathetic stimulation.[23] Together these findings suggest a functional role of the sympathetic nervous system in CBF regulation. In addition, the exponential increase in sympathetic activity that occurs during heavy weightlifting exercise to maximum in healthy humans resulting in systolic blood pressure that exceeds 300 mmHg, extends the cerebral autoregulatory range above 150 mmHg, increases cerebrovascular tone and buffers the pulsatile increases in cerebral perfusion pressure, thereby protecting the brain.[24] In addition, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood strongly regulates CBF, while other physiological factors involved in CBF regulation are partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, cerebral neural activity, and cerebral metabolism[25] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The physiological factors known to influence cerebral blood flow regulation. In addition to these factors, recent studies have emphasized the role of the sympathetic nervous system infl uencing cerebral blood flow. CBF = cerebral blood fl ow, CO2 = carbon dioxide, O2 = oxygen

α-1 adrenergic receptors on the cerebral vasculature

Similar to the systemic vasculature, cerebral vessels are richly innervated with sympathetic nerve fibers connected to α-1 adrenergic receptors that appear to be located on the cerebral arterioles.[14] Although the α-1 adrenergic receptors are the most abundant adrenergic receptors in the brain, their role in the central nervous system is not yet established.[26] The alpha-1 adrenergic receptors are postsynaptic and stimulatory in nature.[26] In the vascular smooth muscle cells, α-1 adrenergic receptors bind to norepinephrine (NE), or other sympathomimetic drugs, and through receptor coupling with its Gq-protein stimulate phospholipase C activity which then promotes hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate producing inositol triphosphate and diacylglycerol.[27] These molecules act as second messengers mediating intracellular Ca2+ release from non-mitochondrial pools and activate protein kinase C, which then leads to a cascade of events leading to activation of contractile proteins and vasoconstriction.[28] The densities of α-1 adrenergic receptors are reported to undergo a diurnal rhythm in the brain regions associated with entrainment to photoperiod demonstrated in animal models.[29] Though several animal models have been used, species difference in the anatomy of the cerebral circulation may lead to contradiction in the results. Recently, age of the animals were also reported to influence the results as sympathetic innervation density and constrictor response to NE in the brain were weak in juvenile rats when compared to mature animals.[30]

The adrenergic receptors are members of the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily of membrane proteins. Based on evidence of α-1 adrenergic receptors heterogeneity, they are subdivided into α-1A, α-1B, and α-1D, with α-1A subtype having higher binding affinities to agonist, such as methoxamine and antagonist 5-methylurapidil. Overexpression of α-1B adrenergic receptors did not result in an increase in blood pressure and studies have reported that α-1B adrenergic receptor is not a significant player in mediating vasoconstriction. Studies have demonstrated α-1D adrenergic receptors to be involved in vascular smooth muscle contraction but less dominant than the α-1A adrenergic receptors.[26] In addition to mediating intracellular Ca2+ release, the α-1 adrenergic receptors are also reported to activate Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent and independent calcium channels.[31] Apart from calcium mobilization, α-1 adrenergic receptors stimulate MAPK signaling pathways and significantly contribute to increased DNA synthesis and cell proliferation in human vascular smooth muscle cells.[32] α-1 adrenergic receptors are also localized in glial cells and may affect brain functions through non-neuronal mechanisms.[33] There are reports of polymorphisms in the α-1 adrenergic receptors, but have not yet been linked to functional consequences unlike members of the β-adrenergic receptors.[26]

Blood brain barrier permeability and cerebral blood flow regulation

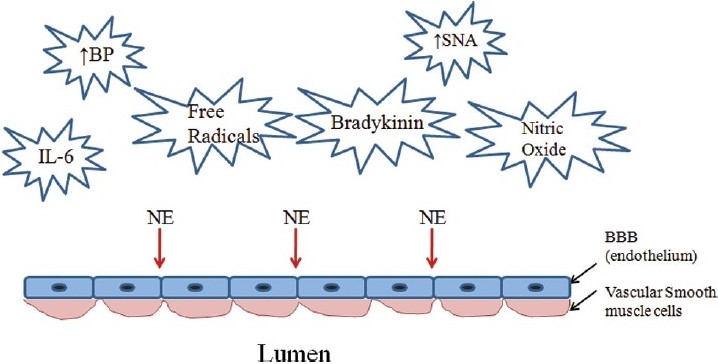

Reports in the past have stated “that vasoactive amines do not penetrate the blood brain barrier (BBB) and only influence cerebral resistance vessels from the outside.”[34] Consequently, they concluded that “the sympathetic nerves do not effectively control the inner vascular smooth muscle of the cerebral vessels.” However, Sandor[35] refuted the impermeability of the BBB and reported that the peripheral adrenergic neurons come in close contact with the smooth muscle layer of the cerebral vessels. The density of α-1 adrenergic receptors in different regions of cerebral vessels also varies among species, which led to the differences in results among several studies.[35] Although there are reports of impermeable tight junctions on the BBB in the capillary endothelium, the tight junctions of the BBB in the endothelium of brain arterioles and venules of the cerebral microvasculature are found to be leaky and subject to greater modulation[36] [Figure 2]. Furthermore, there are reductions in the tightness by rupture of the BBB with increases in arterial pressure,[23] free radical and interlukin-6 concentrations,[37] all of which are abundant during hyperadrenergic disease states.[38] In addition, circulating NE also stimulates IL-6 production.[39] Vasoactive substances, such as bradykinin and nitric oxide, also appear to increase permeability of the BBB through activation of second messenger pathways.[40] The resultant increase in permeability of the BBB is proposed to make the α-1 adrenergic receptors accessible to the circulating NE along with local release of NE from nerve endings within the brain. Mitchell et al,[41] have recently demonstrated NE spillover from the cerebral vasculature into the internal jugular vein and identified that NE spillover originates primarily from the cerebral vasculature outside the BBB, and that the lipophilic metabolite spillover originates from both sides of the BBB. In Mitchell et al.′s[41] findings, it was noted that pure autonomic failure patients had 77% lower brain NE spillover than found in the healthy subjects, indicating that the sympathetic neuron degeneration associated with pure autonomic failure limited the NE spillover.

Figure 2.

The factors and conditions which are reported to modulate the blood brain barrier (BBB) and make it leaky or subject to rupture allowing circulation norepinephrine (NE) to access the alpha-1 adrenergic receptors located within the brain in addition to local release of NE in the brain. IL-6 = interlukin-6; BP = blood pressure; SNA = sympathetic neural activity

Functional role of α-1 adrenergic receptors in cerebral blood flow regulation

Moreover, evidence of functional α-1 adrenoreceptors was demonstrated by an increase in cerebral vascular conductance following an experimentally induced acute hypotension with bilateral thigh cuff occlusion/release technique designed to stimulate the sympathetic nerve activity.[11] The increase in cerebral vascular conductance was attenuated by selective α-1 adrenergic blockade (prazosin) reflecting a sympathetically mediated dynamic control of the cerebral vasculature. In addition, attenuation of sympathetically mediated vascular tone induced by spinal cord stimulation resulted in increases in CBF due to withdrawal of sympathetic activation of the α-1 adrenergic receptors.[22,42] In healthy subjects, a reduction in cerebral tissue oxygenation was reported after infusion of NE.[43] These findings identify the presence of functional α-1 adrenoreceptors in the cerebral vasculature. Recently, Brassard et al.[44] demonstrated a decrease in cerebral tissue oxygenation at rest with a bolus injection of phenylephrine which was attenuated during light-intensity cycling exercise and abolished with high-intensity exercise-mediated increase in cerebral metabolism indicating the presence of “functional sympatholysis”[45] similar to that observed in the peripheral vasculature, where sympathetic activity is overridden by accumulation of local metabolites.[46] Critical closing pressure, an index of cerebral vascular tone, was also demonstrated to increase in relation to increases in sympathetic activity with increases in exercise intensity.[47] These data strongly indicate a functional role of the α-1 adrenergic receptor-mediated sympathetic nerve activity in the cerebral vasculature.

Measurement of static vs. dynamic changes in cerebral blood flow

Static cerebral autoregulation (sCA) refers to the relative steady-state relationship between CBF and arterial blood pressure (ABP), characterized by a positive slope of 0.8% (often referred to as a plateau) increase in CBF/mmHg between the autoregulatory range of 60 to 150 mmHg ABP.[48,49] Dynamic cerebral autoregulation (dCA) corresponds to the transient response of CBF to beat-to-beat fluctuations in ABP during acute changes in arterial pressure.[50,51] Hence, dCA is important for rapidly adjusting the CBF to its steady-state flow, when challenged by acute changes in perfusion pressure.[25] The importance of dCA on sCA and its effect on oxygen delivery to the brain is at the forefront of current research in CBF regulation.[25] Historically, the predominant measurement technique for assessing sCA was the Kety-Schmidt technique using 133Xenon, which required one to establish steady-state conditions for the measure to be valid. This process resulted in elimination of dynamic assessment of CBF resulting from transient changes in ABP. Therefore, the dynamic changes in CBF were undetected, resulting in a reported constant CBF. Consequently, the cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen during exercise has been reported as unchanged.[52] Furthermore, the jugular venous sampling required for the Kety-Schmidt method was compromised, because it is now known that the internal jugular vein is collapsed in the upright position.[53,54] In the upright posture, venous drainage from the brain is dependent on the spinal veins of the vertebral plexus.[55–57] In addition, it is now known that cerebral activation is directly associated with increases in regional CBF and metabolism, as detected by positron emission tomography.[58] With the advent of dynamic noninvasive measurement techniques, such as transcranial Doppler (TCD) of MCA V changes and near infrared spectroscopic analysis of cerebral tissue oxygenation, the dynamic regulation of CBF by dCA, when ABP is rapidly changing, can be accomplished. Because of these techniques, there is a growing body of evidence identifying that increases in sympathetic neural activity result in local release of NE within the brain and circulating NE which can bind to the accessible α-1 adrenergic receptors on the smooth muscle of the cerebral arterioles and influence dCA and sCA.[43,11] The MCA V obtained from TCD does not take into account the vessel diameter which could possibly be increased due to sympathetically mediated decrease in vessel diameter. However, during exercise, the MCA V increases in parallel with the internal carotid artery blood flow.[59,60] This suggests that sympathetic modulation does not significantly alter the diameter of the MCA, and that sympathetic regulation of CBF occurs mainly in the cerebral resistance arterioles rather than in the large cerebral conductance arteries. It is reasonable to propose that if the diameter of the MCA decrease in response to sympathoexcitation, the MCA V would increase; in fact, the opposite occurs and conductance is decreased, indicating that sympathetic vasoconstriction of the cerebral vessels occurs at the small resistance arterioles.

Arterial baroreflex interaction with the cerebral vasculature

Studies in the past were unable to identify any relationship between the cerebral vasculature and its response to carotid baroreceptor stimulation,[61,62] despite cerebral arteries being richly innervated with sympathetic nerve fibers.[8,63] However, a reduction in CBF was observed when sympathetic nerves were activated through sinoaortic deafferentation, a procedure that produces marked elevation of peripheral sympathetic tone and extreme hypertension.[15] Stimulation of the carotid baroreceptors of baboons decreased their CBF, while at the same time maintaining the cerebral inflow pressure.[64] Similar results were obtained in a human study where MCA V decreased during unilateral trigeminal ganglion stimulation.[22] Zhang et al.[65] have demonstrated that dCA is altered with ganglion blockade using trimethaphan and thus speculated a tonic control of the autonomic nervous system in beat-to-beat CBF regulation. Patients with idiopathic orthostatic intolerance exhibit an excessive decline in CBF upon orthostasis despite sustained systemic blood pressure. However, this decline in CBF was abolished with phentolamine blockade of the α-adrenoreceptors during head-up tilt.[19] β-1 adrenergic blockade during dynamic cycling exercise in healthy humans diminished cardiac output as well as MCA V. In addition, because stellate ganglion blockade eliminated the β-1 blockade-induced decreases in MCA V, it was concluded that the exercise pressor reflex-induced sympathoexcitation resulting from underperfused exercising muscle was the cause of the reduction in MCA V.[66] The decrease in MCA V is indicative of an augmentation of sympathetic-mediated vasoconstriction in the cerebral vessels.[67] During recovery from acute hypotension induced by an ischemic thigh cuff occlusion/release protocol,[68] sympathoexcitation was evident from the decrease in cerebral vascular conductance identified by the rate of regulation (RoR), quantifying cerebral autoregulation. The RoR was attenuated by α-1 adrenoreceptor blockade[11] indicating arterial baroreflex control of the cerebral circulation through the sympathetic nervous system. Therefore, we conclude that the arterial baroreflex-mediated alterations of sympathetic nervous system are crucial in the beat-to-beat regulation of CBF.

Conclusion

There is evidence of the dynamic functional role of the α-1 adrenergic receptor control of sympathetic neural activity in the cerebral circulation. It appears that increases in sympathetic activity increases cerebral vascular tone and by interaction with the myogenic properties of the smooth muscle cells of the cerebral vessels results in cerebral vasoconstriction and enhanced CA. Therefore, the use of vasoconstrictor drugs to support a patients’ ABP during hemorrhage, surgery, and emergency care medicine requires further evaluation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Aronson H. Uber nerven und nervendigungen in der Pia Mater. Zeitschrift fur Medizinisce Wissenschaft. 1890;28:594–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedikt M. Uber die innervation des plexus choriodeus inferioir. Virchows Archives fur Pathologie, Anatomie und Phyisiologie. 1874;59:395–400. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willis T. Flesher J. London: 1664. Cerebri anatone, cui accesit nervorum, descriptio etusus. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenblum W, Chen M. Density of perivascular nerves on some cerebral and extracerebral blood vessels. Blood Vessels. 1976;13:374–8. doi: 10.1159/000158107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenblum WI. The “richness” of sympathetic innervation. A comparison of cerebral and extracerebral blood vessels. Stroke. 1976;7:270–1. doi: 10.1161/01.str.7.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:347–60. doi: 10.1038/nrn1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edvinsson L. Neurogenic mechanisms in the cerebrovascular bed.Autonomic nerves, amine receptors and their effects on cerebral blood flow. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1975;427:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson E, Rennels M. Innervation of intracranial arteries. Brain. 1970;93:475–90. doi: 10.1093/brain/93.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen KC, Owman C. Adrenergic innervation of pial arteries related to the circle of Willis in the cat. Brain Res. 1967;6:773–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(67)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamner JW, Tan CO, Lee K, Cohen MA, Taylor JA. Sympathetic control of the cerebral vasculature in humans. Stroke. 2010;41:102–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogoh S, Brothers RM, Eubank WL, Raven PB. Autonomic neural control of the cerebral vasculature: Acute hypotension. Stroke. 2008;39:1979–87. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang R, Behbehani K, Levine BD. Dynamic pressure-flow relationship of the cerebral circulation during acute increase in arterial pressure. J Physiol. 2009;587:2567–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lassen NA. Autoregulation of Cerebral Blood Flow. Circ Res. 1964;15(SUPPL):201–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitch W, MacKenzie ET, Harper AM. Effects of decreasing arterial blood pressure on cerebral blood flow in the baboon.Influence of the sympathetic nervous system. Circ Res. 1975;37:550–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heistad DD, Marcus ML, Gross PM. Effects of sympathetic nerves on cerebral vessels in dog, cat, and monkey. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:H544–52. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.5.H544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strandgaard S, MacKenzie ET, Sengupta D, Rowan JO, Lassen NA, Harper AM. Upper limit of autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in the baboon. Circ Res. 1974;34:435–40. doi: 10.1161/01.res.34.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eklof B, Ingvar DH, Kagstrom E, Olin T. Persistence of cerebral blood flow autoregulation following chronic bilateral cervical sympathectomy in the monkey. Acta Physiol Scand. 1971;82:172–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1971.tb04956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busija DW, Heistad DD. Factors involved in the physiological regulation of the cerebral circulation. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;101:161–211. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan J, Shannon JR, Black BK, Paranjape SY, Barwise J, Robertson D. Raised cerebrovascular resistance in idiopathic orthostatic intolerance: evidence for sympathetic vasoconstriction. Hypertension. 1998;32:699–704. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearce WJ, D’Alecy LG. Hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasoconstriction in dogs. Stroke. 1980;11:190–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.11.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer JS, Yoshida K, Sakamoto K. Autonomic control of cerebral blood flow measured by electromagnetic flowmeters. Neurology. 1967;17:638–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.7.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visocchi M, Cioni B, Pentimalli L, Meglio M. Increase of cerebral blood flow and improvement of brain motor control following spinal cord stimulation in ischemic spastic hemiparesis. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1994;62:103–7. doi: 10.1159/000098604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bill A, Linder J. Sympathetic control of cerebral blood flow in acute arterial hypertension. Acta Physiol Scand. 1976;96:114–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1976.tb10176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogoh S, Fadel PJ, Zhang R, Selmer C, Jans O, Secher NH, et al. Middle cerebral artery flow velocity and pulse pressure during dynamic exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1526–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00979.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogoh S, Ainslie PN. Regulatory mechanisms of cerebral blood flow during exercise: New concepts. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2009;37:123–9. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181aa64d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piascik MT, Perez DM. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors: New insights and directions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:403–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olesen J. The effect of intracarotid epinephrine, norepinephrine, and angiotensin on the regional cerebral blood flow in man. Neurology. 1972;22:978–87. doi: 10.1212/wnl.22.9.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guimaraes S, Moura D. Vascular adrenoceptors: An update. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:319–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiland NG, Wise PM. Estrogen alters the diurnal rhythm of alpha 1-adrenergic receptor densities in selected brain regions. Endocrinology. 1987;121:1751–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-5-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omar NM, Marshall JM. Age-related changes in the sympathetic innervation of cerebral vessels and in carotid vascular responses to norepinephrine in the rat: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:314–22. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01251.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minneman KP. Alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes, inositol phosphates, and sources of cell Ca2+ Pharmacol Rev. 1988;40:87–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu ZW, Shi XY, Lin RZ, Chen J, Hoffman BB. alpha1-Adrenergic receptor stimulation of mitogenesis in human vascular smooth muscle cells: role of tyrosine protein kinases and calcium in activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:28–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulik A, Haentzsch A, Luckermann M, Reichelt W, Ballanyi K. Neuron-glia signaling via alpha(1) adrenoceptor-mediated Ca(2+) release in Bergmann glial cells in situ. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8401–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08401.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strandgaard S, Sigurdsson ST. Point:Counterpoint: Sympathetic activity does/does not influence cerebral blood flow.Counterpoint: Sympathetic nerve activity does not influence cerebral blood flow. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1366. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90597.2008a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandor P. Nervous control of the cerebrovascular system: Doubts and facts. Neurochem Int. 1999;35:237–59. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbott NJ. Dynamics of CNS barriers: Evolution, differentiation, and modulation. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:5–23. doi: 10.1007/s10571-004-1374-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1379–406. doi: 10.1152/physrev.90100.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Patay B, Kurz B, Mentlein R. Effect of transmitters and co-transmitters of the sympathetic nervous system on interleukin-6 synthesis in thymic epithelial cells. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1999;6:45–50. doi: 10.1159/000026363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayhan WG. Regulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. Microcirculation. 2001;8:89–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2001.tb00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell DA, Lambert G, Secher NH, Raven PB, van Lieshout J, Esler MD. Jugular venous overfl ow of noradrenaline from the brain: A neurochemical indicator of cerebrovascular sympathetic nerve activity in humans. J Physiol. 2009;587:2589–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel S, Huang DL, Sagher O. Sympathetic mechanisms in cerebral blood flow alterations induced by spinal cord stimulation. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:754–61. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brassard P, Seifert T, Secher NH. Is cerebral oxygenation negatively affected by infusion of norepinephrine in healthy subjects? Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:800–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brassard P, Seifert T, Wissenberg M, Jensen PM, Hansen CK, Secher NH. Phenylephrine decreases frontal lobe oxygenation at rest but not during moderately intense exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1472–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01206.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Remensnyder JP, Mitchell JH, Sarnoff SJ. Functional sympatholysis during muscular activity.Observations on influence of carotid sinus on oxygen uptake. Circ Res. 1962;11:370–80. doi: 10.1161/01.res.11.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller DM, Fadel PJ, Ogoh S, Brothers RM, Hawkins M, Olivencia-Yurvati A, et al. Carotid baroreflex control of leg vasculature in exercising and non-exercising skeletal muscle in humans. J Physiol. 2004;561:283–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogoh S, Brothers RM, Jeschke M, Secher NH, Raven PB. Estimation of cerebral vascular tone during exercise; Evaluation by critical closing pressure in humans. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:678–85. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.052340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heisted D, Kontos H. Washington, DC: American Physiological Society; 1983. Handbook of Physiology. Peripheral Circulation and Organ Blood Flow, Part I. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucas SJ, Tzeng YC, Galvin SD, Thomas KN, Ogoh S, Ainslie PN. Influence of changes in blood pressure on cerebral perfusion and oxygenation. Hypertension. 2010;55:698–705. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panerai RB. Cerebral autoregulation: From models to clinical applications. Cardiovasc Eng. 2008;8:42–59. doi: 10.1007/s10558-007-9044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tiecks FP, Lam AM, Aaslid R, Newell DW. Comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation measurements. Stroke. 1995;26:1014–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madsen PL, Sperling BK, Warming T, Schmidt JF, Secher NH, Wildschiodtz G, et al. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity and cerebral blood flow and O2 uptake during dynamic exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:245–50. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dawson EA, Secher NH, Dalsgaard MK, Ogoh S, Yoshiga CC, Gonzalez-Alonso J, et al. Standing up to the challenge of standing: A siphon does not support cerebral blood flow in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R911–4. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00196.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gisolf J, van Lieshout JJ, van Heusden K, Pott F, Stok WJ, Karemaker JM. Human cerebral venous outflow pathway depends on posture and central venous pressure. J Physiol. 2004;560:317–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alperin N, Lee SH, Sivaramakrishnan A, Hushek SG. Quantifying the effect of posture on intracranial physiology in humans by MRI flow studies. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:591–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cirovic S, Walsh C, Fraser WD, Gulino A. The effect of posture and positive pressure breathing on the hemodynamics of the internal jugular vein. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74:125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valdueza JM, von Munster T, Hoffman O, Schreiber S, Einhaupl KM. Postural dependency of the cerebral venous outflow. Lancet. 2000;355:200–1. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04804-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Secher NH, Seifert T, Van Lieshout JJ. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise: implications for fatigue. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:306–14. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00853.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hellstrom G, Fischer-Colbrie W, Wahlgren NG, Jogestrand T. Carotid artery blood flow and middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity during physical exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:413–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang SY, Sun S, Droma T, Zhuang J, Tao JX, McCullough RG, et al. Internal carotid arterial flow velocity during exercise in Tibetan and Han residents of Lhasa (3,658 m) J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:2638–42. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.6.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heistad DD, Marcus ML, Said SI, Gross PM. Effect of acetylcholine and vasoactive intestinal peptide on cerebral blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:H73–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.1.H73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rapela CE, Green HD, Denison AB., Jr Baroreceptor reflexes and autorregulation of cerebral blood flow in the dog. Circ Res. 1967;21:559–68. doi: 10.1161/01.res.21.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edvinsson L. Sympathetic control of cerebral circulation. Trends Neurosci. 1982;5:425–9. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ponte J, Purves MJ. The role of the carotid body chemoreceptors and carotid sinus baroreceptors in the control of cerebral blood vessels. J Physiol. 1974;237:315–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Iwasaki K, Wilson TE, Crandall CG, Levine BD. Autonomic neural control of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Circulation. 2002;106:1814–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031798.07790.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ide K, Boushel R, Sorensen HM, Fernandes A, Cai Y, Pott F, et al. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity during exercise with beta-1 adrenergic and unilateral stellate ganglion blockade in humans. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;170:33–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ide K, Secher NH. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:397–414. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aaslid R, Lindegaard KF, Sorteberg W, Nornes H. Cerebral autoregulation dynamics in humans. Stroke. 1989;20:45–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]