Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the hepatoprotective activity of the aqueous extract of the aerial parts of Portulaca oleracea (P. oleracea) in combination with lycopene against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in rats.

Materials and Methods:

Hepatotoxicity was induced in male Wistar rats by intraperitoneal injection of carbon tetrachloride (0.1 ml/kg b.w for 14 days). The aqueous extract of P. oleracea in combination with lycopene (50 mg/kg b.w) was administered to the experimental animals at two selected doses for 14 days. The hepatoprotective activity of the combination was evaluated by the liver function marker enzymes in the serum [aspartate transaminases (AST), alanine transaminases (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (Alk.P), total bilirubin (TB), total protein (TP) and total cholesterol (TC)], pentobarbitone induced sleeping time (PST) and histopathological studies of liver.

Results:

Both the treatment groups showed hepatoprotective effect against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity by significantly restoring the levels of serum enzymes to normal which was comparable to that of silymarin group. Besides, the results obtained from PST and histopathological results also support the study.

Conclusions:

The oral administration of P. oleracea in combination with lycopene significantly ameliorates CCl4 hepatotoxicity in rats.

Keywords: Hepatotoxicity, hepatoprotective activity, lycopene, Portulaca oleracea

Introduction

Liver is the key organ regulating homeostasis in the body. It is involved with almost all the biochemical pathways related to growth, fight against disease, nutrient supply, energy production and reproduction. Because of its unique metabolism and relationship to the gastrointestinal tract, the liver is an important target for toxicity produced by drugs, xenobiotics and oxidative stress.[1] More than 900 drugs, toxins and herbs have been reported to cause liver injury and drugs account for 20–40% of all instances of fulminant liver failure. In the absence of reliable liver protection drugs in modern medicine, a large number of medicinal preparations are recommended for the treatment of liver disorders and quite often claimed to offer significant relief. Attempts are being made globally to get scientific evidences for these traditionally reported herbal drugs. This scenario provides a severe necessity to carry out research in the area of hepatotoxicity.

Portulaca oleracea (P. oleracea) belonging to the family “Portulacaceae” is a herbaceous plant widely distributed throughout the world. It contains many biologically active compounds and is a source of many nutrients like free oxalic acids, alkaloids, omega-3 fatty acids, coumarins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, anthraquinone, protein,[2] α-linolenic acid and β-carotene[3,4] mono terpene glycoside,[5] N-trans-feruloyltyramine.[6] It was also found to contain vitamin C, oleoresins-I and II, saponins, tannins, saccharides, triterpenoids, α-tocopherol and glutathione.[7–9] The high contents of a variety of phytoconstituents present in this plant were considered to be responsible for the biological activities reported for the plant like antibacterial, antifungal,[10] analgesic, anti-inflammatory,[11] anti-fertility,[12] muscle relaxant[13] and wound healing properties.[14] This plant which is normally used as a vegetable to prepare curry by the native people of Andhra Pradesh is used in combination with tomato. In our work, we thus made an attempt to study the hepatoprotective activity of the aqueous extract of this plant in combination with lycopene and to study the possibility of any interactions.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar albino rats were used for the study. The animals were housed in groups of six and maintained under standard conditions (27 ± 2°C, relative humidity 44–56% and light and dark cycles of 10 and 14 h respectively), fed with standard rat diet and purified drinking water ad libitum one week before and during the experiment. All the experiments and protocols described in the present study were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC) of Sri Padmavathi School of Pharmacy, Tiruchanoor, Tirupathi (CPCSEA Reg No. 1016/a/06/CPCSEA/002/2008).

Plant Material

The aerial parts of the plant “Portulaca oleracea” were collected from in and around Tirumala hills. They were identified and authentified by Prof. N. Yashodamma, Department of Botany, S.V. University, Tirupathi.

Preparation of P. oleracea Extract (PO)

The aerial parts of the plant were shade dried and powdered. The powder was then decocted in purified boiling water in the ratio of 1:9 for 30 min. This decoction was kept for an overnight and filtered. The filtrate was stored in screwed glass vials at 2–8°C. Weight/ml was estimated and then used for dosing of animals.

Preparation of Lycopene (LE)

Tomato sauce (Maggi) was obtained from the local market and subjected to loss on drying. Considering the total solid content as lycopene, it was dissolved in sufficient amount of 0.5% CMC in purified water so as to get a solution containing the required dose of 50 mg/kg b.w.

Drugs and Chemicals

Silymarin (Sigma) was used as the standard drug. Kits (Span Diagnostics Ltd., India and Excel diagnostics Ltd., India) were used for biochemical estimations.

Pharmacological Study

Acute oral toxicity study was performed as per OECD-423 guidelines (Ecobichon, 1997). The PO was administered orally in doses of 5, 50, 300, 2000 mg/kg bodyweight to groups of rats (n = 3) and the percentage mortality was recorded over a period of 24 h. During the first 1 h of drug administration, rats were observed for gross behavioral changes as described by Irwin et al. (1968).[15]

Experimental Design

The animals were divided into five groups of six animals each. Except the normal group, all the other groups received carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) 50% v/v in olive oil at a dose of 0.1 ml/kg i.p for 14 days. Normal group received plain olive oil orally. The standard group received silymarin 50 mg/kg orally. Test 1 group received PO 250 mg/kg + LE 50 mg/kg orally while test 2 group received PO 500 mg/kg + LE 50 mg/kg orally. On the 14th day, blood was collected from each animal for serum analysis. The rats were sacrificed and their livers were removed. One lobe was then fixed in 10% formalin for histopathological studies.

Marker Enzymes of Liver Damage

Serum samples were processed to determine serum AST, ALT, Alk.P, TB, TP and TC using standard diagnostic kits.

Pentobarbitone Induced Sleeping Time[16]

The rats were kept on standard diet. Experiments were set as mentioned earlier. Twenty four hours after the last treatment; pentobarbitone sodium in water for injection (35 mg/kg) was administered i.p. Food was withdrawn and water given ad libitum 12 h before pentobarbitone injection. All the experiments were conducted between 09.00 am and 5.00 pm in a temperature controlled room. The animals were placed on table after loss of righting reflex. The time interval between loss and regain of righting reflex was measured as pentobarbitone sleeping time (PST). This functional parameter was used to determine the metabolic activity of the liver.

Histopathology

After draining the blood, the livers were excised, washed with normal saline and processed separately for histopathological observations.

Statistical Analysis

All the data was expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between more than two groups was tested using one way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test using computer based fitting program (Prism, Graph pad.). Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05.

Results

In the acute toxicity study, it was observed that none of the doses of PO (i.e. 5, 50 300, 2000 mg/kg) produced any lethality among the tested animals when administered as a single dose.

There was a tremendous and dramatic rise in AST, ALT, Alk.P, TB and TC levels of CCl 4 treated group when compared to the normal. The test groups 1 and 2 showed a decline in these parameters which was almost comparable to that of the standard group treated with silymarin [Table 1].

Table 1.

Effect of P. oleracea in combination with lycopene on serum biochemical parameters

The TP levels witnessed a fall in the CCl4 treated group whereas the test groups 1 and 2 showed a remarkable increase in the protein levels similar to silymarin treated group [Table 1].

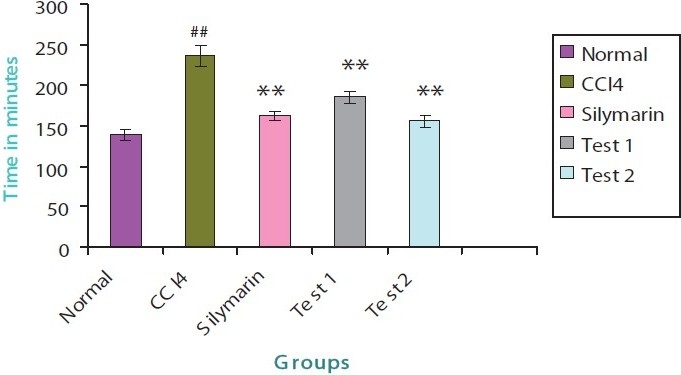

The PBT was significantly increased in case of CCl 4 group when compared to that of normal group. There was a marked reduction in the sleeping time in case of silymarin group, test groups 1 and 2 when compared to that of CCl4 group [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Pentobarbitone induced sleeping time

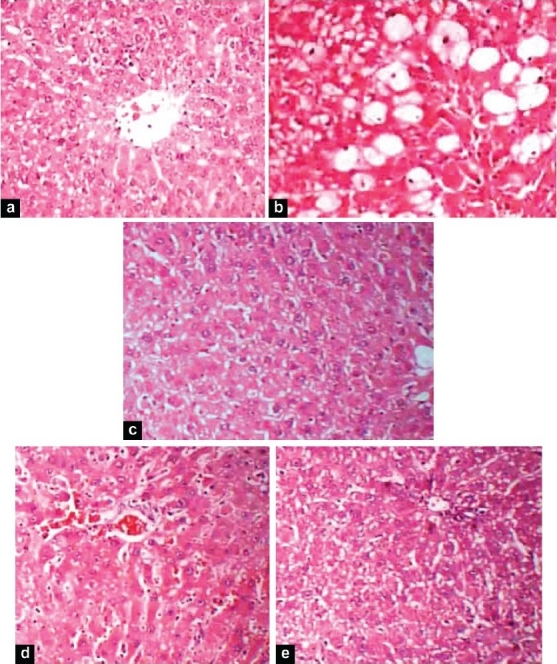

The histopathological studies revealed an extensive hepatic damage in case of CCl4 group. Silymarin and both the test groups 1 and 2 showed a protective effect by decreasing the extent of centrilobular necrosis and steatosis when compared to CCl4 group [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Histopathology of rat livers of all the five groups (a) Normal group; (b) CCl4 group: 0.1 ml/kg CCl4; (c) Silymarin group: 0.1 ml/kg CCl4 + 50 mg/kg silymarin; (d) Test 1: 0.1 ml/kg CCl4 + 250 mg/kgPO+ 50 mg/kg LE; (e) Test 2: 0.1 ml/kg CCl4 + 500 mg/kg PO+ 50 mg/kg LE

Discussion

Liver plays a major role in detoxification and excretion of many endogenous and exogenous compounds, any injury or impairment of its function may lead to several implications on one's health. Management of liver diseases is still a challenge to modern medicine. Conventional drugs used in the treatment of liver diseases are often inadequate. It is therefore necessary to search for alternative drugs for the treatment of liver diseases to replace the currently used drugs of doubtful efficacy and safety.

Carbon tetrachloride is a routinely used hepatotoxin for experimental study of liver diseases. Administration of CCl 4 causes acute liver damage that mimics natural causes. It mediates changes in liver function that ultimately leads to destruction of hepatocellular membrane. Cytochrome P-450 activates CCl4 to form various free radicals (trichloromethyl, Cl3 C-CCl3 (hexachloroethane), COCl2 (phosgene), etc.) which are involved in the pathogenesis of liver damage in chain reactions resulting in peroxidation of lipids, covalent binding of macromolecules, disruption of metabolic mechanisms in mitochondria, decreasing levels of phospholipids, increasing triglyceride levels, inhibition of calcium pumps of microsomes thus leading to liver necrosis.[17]

The acute toxicity study revealed the absence of lethality among the tested animals when the extract was administered as a single dose (5, 50, 300, 2000 mg/kg). There were no signs of any gross behavioral changes except for an increase in urination indicating the safe use of the extract.

Necrosis or membrane damage releases the enzymes into circulation and hence it can be measured in the serum. The reversal of increased serum enzymes in CCl4-induced liver damage by the extract may be due to the prevention of the leakage of intracellular enzymes by its membrane stabilizing activity.

Amino transferases contribute a group of enzymes that catalyze the interconversion of amino acids and α-keto acids by the transfer of amino groups. These are liver specific enzymes and are considered to be very sensitive and reliable indices for necessary hepatotoxic as well as hepatoprotective or curative effect of various compounds. Both AST and ALT levels increase due to toxic compounds affecting the integrity of the liver cells.[18] Decreased levels of transaminases indicate stabilization of plasma membrane and protection of hepatocytes against damage caused by hepatotoxin. This is in agreement with the commonly accepted view that serum levels of transaminases return to normal with the healing of hepatic parenchyma and the regeneration of hepatocytes.

Alkaline phosphatase is a membrane bound glycoprotein enzyme with a high concentration in sinusoids and endothelium. This enzyme reaches the liver mainly from the bone. It is excreted into the bile; therefore its elevation in serum occurs in hepatobiliary diseases.[19] Serum alkaline phosphatase is related to the functioning of hepatocytes and increase in its activity is due to the increased synthesis in presence of biliary pressure. The results of the present study indicate that the test groups probably stabilize the hepatic plasma membrane from CCl 4-induced damage which is evident from Table 1.

Reduction of alkaline phosphatase levels with concurrent depletion of raised bilirubin levels suggests the stability of the biliary function during injury with CCl4.

The liver is known to play a significant role in the serum protein synthesis, being the source of plasma albumin and fibrinogen and also the other important components like α and β-globulin. The liver is also concerned with the synthesis of γ-globulin. The metabolic biotransformation of amino acid in liver by synthesis, transamination, etc., may be impaired due to the escape of both non-proteins and protein nitrogenous substances from injured cells as mediated by a raise in the serum enzyme levels of ALP, AST and ALT. The reduction in the total protein (TP) is attributed to the initial damage produced and localized in the endoplasmic reticulum which results in the loss of cytochrome P-450 enzymes leading to its functional failure with a decrease in protein synthesis and accumulation of triglycerides leading to fatty liver.[20] Both the test groups enhanced the synthesis of TP which accelerates the regeneration process and the protection of liver cells that is clearly demonstrated in Table 1. Therefore, the increased level of total protein in serum indicates the hepatoprotective activity.

Inhibition of bile acids synthesis from cholesterol, which is synthesized in liver or derived from plasma lipids leading to increase in cholesterol levels, was also resulted due to CCl4 intoxication. Significant suppression of cholesterol levels by the test groups suggests that the bile acids synthesis inhibition was reversed.

The extent of hepatic damage is assessed by histological evaluation along with the level of various biochemical parameters in circulation. The animals in the CCl4 group showed severe hepatotoxicity evidenced by profound steatosis, centrilobular necrosis, ballooning degeneration, nodal formation and fibrosis as compared to the normal hepatic architecture of the normal group animals which is clearly seen in Figure 2. Test 2 showed the healing of damaged parenchyma which was comparable to that of the standard group treated with silymarin.

Drug metabolizing capacity of the liver is severely affected due to damaging effects of CCl4, thus resulting in the prolongation of pentobarbitone induced sleeping time. It has been established that since the barbiturates are metabolized almost exclusively in the liver, the sleeping time after a given dose is a measure of hepatic metabolism.[21] If there is any liver damage, as in this case by CCl4 intoxication, the sleeping time after a given dose of the barbiturate will be prolonged, because the amount of the barbiturate metabolized per unit time will be less. Here silymarin group, test groups 1 and 2 have reduced the prolongation of sleeping time induced by pentobarbitone indicating the improvement in the metabolic activity of the liver which is clear from Figure 1.

The efficacy of any hepatoprotective drug is dependent on its capacity of either reducing the harmful effect or restoring the normal hepatic physiology that has been disturbed by a hepatotoxin. The silymarin group and both the test groups decreased CCl 4 induced elevated enzyme levels, indicating the protection of structural integrity of hepatocytic cell membrane or regeneration of damaged liver cells.

Phytoconstituents like the flavonoids,[22] triterpenoids,[23] saponins[24] and alkaloids[25] are known to possess hepatoprotective activity. The presence of flavanoids (whose presence was confirmed in the preliminary phytochemical screening) in our extract may be responsible for its antioxidant and thus hepatoprotective activity.

Both the test groups 1 and 2 contain the lycopene extract and also the plant extract but it may not be very difficult to judge whether the activity is attributed because of which ingredient. Lycopene being a proven antioxidant has the capability of hepatoprotection. Keeping its concentration constant in both the groups helps us to define whether the plant extract has the hepatoprotective potential or not. In all the tests, test group 2 showed a better protective activity than test group 1. This clearly indicates that the plant has hepatoprotective potential which was independent of the activity of lycopene (since its concentration was kept constant).

The potential usefulness of the extract in clinical conditions associated with liver damage is still to be demonstrated. Investigations are needed for the isolation of the active principle responsible for hepatoprotective activity and research works are needed to be carried out with regard to intoxication with other models such as iron, alcohol etc to prove its efficacy.

The present findings provide scientific evidence to the ethno medicinal use of this plant genetic resource by the tribal people in treating jaundice.

In summary, this study suggests that the oral administration of P. oleracea in combination with lycopene significantly ameliorates CCl4 hepatotoxicity in rats. The extracts may be protecting the liver by free radical scavenging activity and thus preventing peroxidation of lipids of the endoplasmic reticulum. And this may be due to the presence of flavonoids in the extract (whose presence was confirmed in the preliminary phytochemical screening). The study also rules out the presence of any antagonistic effect of the combination indicating a synergistic effect only.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Jaeschke H, Gores GJ, Cederbaum AI, Hinson JA, Pessayre D, Lemasters JJ. Mechanisms of hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:166–76. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezekwe MO, Omara-Alwala TR, Membrahtu T. Nutritive characterization of purslane accessions as influenced by planting date. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1999;54:183–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1008101620382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu LX, Howe P, Zhou YF, Xu ZH, Hocart C, Zhang R. Fatty acids and b-carotene in Australian purslane (Portulaca oleracea) varieties. J Chromatogr. 2000;893:207–13. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00747-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbosa-Filho JM, Alencar AA, Nunes XP, Tomaz AC, Sena Filho JG, Athayde Filho PF, et al. Sources of alpha, beta, gamma, delta and epsilon-carotenes: A twentieth century review. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2008;18:135–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakai NK, Okamoto, Shizuru Y, Fukuyama Y, Portuloside A. a monoterpene glucoside from Portulaca oleracea. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:1625–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizutani M. Factors responsible for inhibiting the mortality of zoospores of the phytopathogenic fungus Aphanomyces cochlioides isolated from the non-host plant Portulaca oleracea. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:236–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee A, Chandra S, Pakrashi The treatise on Indian medicinal plants. Publ Inform Directorate. 1956;1:243–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simopoulous AP, Norman HA, Gillaspy, Duke JA. Common purslane: A source of omega-3 fatty acids and anti-oxidants. J Am Coll Nutr. 1992;11:374–82. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1992.10718240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prashanth KL, Jadav H, Thakurdesai P, Nagappa AN. Cosmetic potential of herbal extracts. Nat Prod Radiat. 2005;4:351. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh KB, Chang IM, Hwang KI, Mar W. Detection of anti-fungal activity in Portulaca oleracea by a single cell bioassay system. J Phytother Res. 2002;14:329–32. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200008)14:5<329::aid-ptr581>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan K, Islam MW, Kamil M, Radhakrishna R, Zakaria MN, Habibullah M, et al. The analgesic and anti-infammatory effects of Portulaca oleracea Linn. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:445–51. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verma OP, Kumar S, Chatterjee SN. Antifertility effects of common edible Portulaca oleracea on the reproductive organs of male albino mice. Indian J Med Res. 1982;75:301–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parry O, Marks JA, Okwuasab FK. The skeletal muscle relaxant action of Portulaca oleracea: Role of potassium ions.J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993;49:187–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90067-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasheed AN, Affif FU, Disi AM. Simple evaluation of the wound healing activity of crude extracts of Portulaca oleracea in Mus musculus JVJ-1. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;68:131–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irwin . The organization of screening. In: Turner Robert A., editor. Screening methods in Pharmacology. India: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand KK, Gupta VN, Rangari VD, Chandan BK. Structure and hepatoprotective activity of bioflavonoid from Canarium manii. Planta Med. 1992;58:493–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seakins A, Robinson DS. The effect of the administration of carbon tetrachloride on the formation of plasma lipoproteins in rats. Biochem J. 1963;86:401–7. doi: 10.1042/bj0860401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramoniam A, Pushpagada P. Development of phytomedicines for liver diseases. Indian J Pharmacol. 1999;31:166–75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burtes CA, Ashwood ER. Philadelphia: WB Sunders Co; 1986. Textbook of clinical chemistry; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suresh Kumar SV, Sujatha C, Syamala J, Nagasudha B, Mishra SH. Hepatoprotective activity of extracts from Pergularia daemia Forsk. against Carbon tetrachloride induced toxicity in rats. Phcog Mag. 2007;3:11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogel G. Natural substances with effects on the liver. In new natural products and plant drugs with pharmacological, biological or therapeutic activity. In: Wagner H, Wolff P, editors. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baek NL, Kim YS, Kyung JS, Park KH. Isolation of anti-hepatotoxic agents from the roots of Astralagus membranaceous. Korean J Pharmacog. 1996;27:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong X, Chen W, Cui J, Yi S, Zhang Z, Li K. effects of ursolic acid on liver protection and bile secretion. Zhong Yao Cai. 2003;26:578–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran QI, Adnyana IK, Tezuka Y, Nagaoka T, Tran QK, Kadota S. Triterpene saponins from Vietnamese ginseng (Panax vietnamensis) and their hepatocyte protective activity. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:456–61. doi: 10.1021/np000393f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vijayan P, Prashanth HC, Dhanraj SA, Badami S, Suresh B. hepatoprotective effect of total alkaloid fraction of Solanum pseudocapsicum leaves. Pharmaceut Biol. 2003;41:443–8. [Google Scholar]