Abstract

Objective:

To study the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients receiving clozapine.

Materials and Methods:

For this study, 100 patients attending the psychiatry outpatient clinic of a tertiary care hospital who were receiving clozapine for more than three months were evaluated for the presence of metabolic syndrome using the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and modified National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP-III) criteria.

Results:

Forty-six patients fulfilled IDF criteria and 47 met modified NCEP ATP-III criteria of metabolic syndrome. There was significant correlation between these two sets of criteria used to define the metabolic syndrome (Kappa value –0.821, P < 0.001). Among the individual parameters studied, increased waist circumference was the most common abnormality, followed by abnormal blood glucose levels and elevated triglyceride levels. All these abnormalities were seen in more than half (52-61%) of the patients. When the sample was divided into two groups, i.e., those with and without metabolic syndrome, patients with metabolic syndrome had significantly higher body mass index and had spent more time in school. Logistic regression analysis revealed that these two variables together explained about 19% of the variance in metabolic syndrome (adjusted r2 = 0193; F = 12.8; P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

The findings of the present study suggest that metabolic syndrome is highly prevalent in subjects receiving clozapine.

Keywords: Clozapine, India, metabolic syndrome, prevalence

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is defined as a cluster of clinical and laboratory abnormalities including abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) high levels of cholesterol, and high levels of triglycerides.[1] Those with the syndrome have a twofold increase in cardiovascular mortality and a 1.5 fold increase in all-cause mortality.[2] Various criteria have been used to define MS. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria a person is considered to have metabolic syndrome if he has high waist circumference (>80 cm for females and >90 cm for males of Asian origin) and at least two of the following criteria are fulfilled: Systolic blood pressure ≥130 and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mm of Hg (or on treatment for hypertension), triglyceride levels >150 mg/dl (or on specific treatment for this abnormality), HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dl for male and <50 mg/dl for females (or on specific treatment for this abnormality), fasting blood sugar more than 100 mg/dl (or on treatment for diabetes mellitus).[3] The MS criteria according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP-III) are similar with respect to specific abnormalities as defined by IDF, except that the criterion for waist circumference (>88 cm for females and >102 for males) is different and not mandatory. The presence of any of the three is sufficient.[4] According to modified NCEP ATP-III criteria the waist circumference criterion for Asians is relaxed to >90 cm for males and >80 cm for females.[5]

Several studies have found an elevated rate of MS, ranging from 19–68% among patients with schizophrenia.[6] This is significantly higher than that found among healthy controls.[7–9] Several factors could explain the high prevalence of MS in schizophrenia, including improper diet, lack of exercise, cigarette smoking, and stress, as well as abnormalities of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.[10] More recently, treatment with antipsychotics has emerged an important risk factor for MS in schizophrenia.[10] Given the prior evidence linking them to weight gain, hyperglycemia, and lipid abnormalities, second-generation antipsychotics have been particularly linked with an elevated risk of MS.[10]

Among second-generation antipsychotics, clozapine is believed to carry the greatest liability for weight gain and diabetes mellitus.[11,12] It has been hypothesized that antipsychotic-induced weight gain contributes to the development of MS, although a direct diabetogenic effect has also been suggested. Thus, a higher prevalence of MS among patients on clozapine treatment was always anticipated. However, this was confirmed only very recently by a study from USA, which reported a prevalence rate of 54% among patients on clozapine, which was more than twice the rate (21%) found in the matched normal comparison group.[8] Since then a number of other studies have reported prevalence rates varying from 11–64% among patients on clozapine.[13–17] Several potential predictors of MS such as age, body mass index, duration of clozapine treatment have also emerged from these studies, although results in this regard have not always been consistent. A high prevalence of MS among patients with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses has also been found among a few Indian studies on the subject,[18–20] though none have specifically focused on clozapine. On the other hand, a recent comparison of Asian and Caucasian patients on clozapine found differential emergence of certain metabolic abnormalities like hypertension and weight gain in these two ethnic groups.[21]

This prompted the present study which attempted to evaluate the extent of MS among patients of schizophrenia on clozapine treatment and examine the demographic, clinical and metabolic parameters associated with MS in this population.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out at the outpatient psychiatry clinic of a multi-specialty tertiary-care hospital in north India. Adult male and female patients who were on clozapine (75-800 mg/day) for more than three months were invited to participate. Hundred patients diagnosed as per International Classification of Diseses-tenth Revision (ICD-10) by a consultant psychiatrist participated in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Departmental Research Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients who were part of this research. Socio-demographic and clinical details of all the subjects was recorded in structured formats. Current level of functioning was assessed using Global Assessment for Functioning (GAF) scale.

Metabolic and Anthropometric Assessments

Body weight was measured in kilogram (kg) using a common bathroom scale and height in centimeters (cm) by a calibrated scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from the weight and height (kg/m2). Waist circumference, in centimeters (cm), was measured midway between the inferior costal margin and the superior border of the iliac crest, at the end of normal expiration while standing. Blood pressure (BP) was measured using standard mercury manometer in supine position. At least two readings at 5-min intervals were recorded and if high blood pressure (≥140/90) was noted a third reading was taken after 30 min; the lowest of these readings was included for analysis. Fasting venous blood sample were collected under aseptic condition to measure the blood sugar (FBS), triglycerides (TGA) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels.

Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed using both IDF criteria and modified NCEP ATP-III criteria.[3–5]

All patients with metabolic abnormalities were informed, educated about the need for proper diet and regular exercise, and referred for specialist care whenever required.

The SPSS Version 14.0 for Windows (Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for analysis. Chi-Square and t-tests were used for comparisons and a logistic regression was performed to examine the influence of independent variables on the presence of MS.

Results

Profile of the Sample

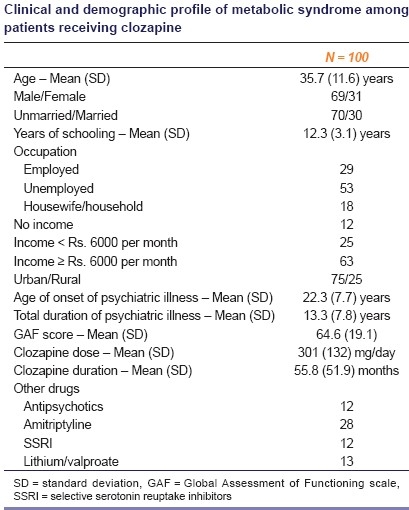

Consecutive sampling was done and patients who were suitable for inclusion were approached, but only 100 patients consented and completed all assessments. The majority of the patients were diagnosed to have schizophrenia (88%), with the undifferentiated subtype being the most common (48%), followed by the paranoid subtype (36%). Three subjects each were diagnosed to have schizoaffective disorder, bipolar affective disorder and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. Two subjects had persistent delusional disorder. Three-fourths of the sample had been on clozapine for more than a year, with more than two-thirds at doses of 250 mg/day or more. More than two-thirds (69%) of the patients were male and the rest were females. Other demographic, clinical and treatment details are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic profile of metabolic syndrome among patients receiving clozapine

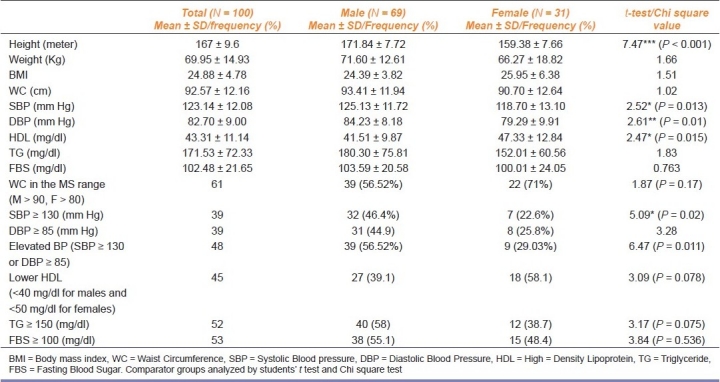

Metabolic Parameters

Details are included in Table 2. Forty-six patients fulfilled the IDF criteria and 47 met modified NCEP ATP-III criteria for MS. There was significant correlation between these two sets of criteria used to define MS (Kappa value – 0.821, P < 0.001). The prevalence of MS was slightly higher in females (48.38%) compared to males (46.37%). Among the individual parameters increased waist circumference was the most common abnormality, followed by abnormal blood glucose levels and elevated triglyceride levels. All these abnormalities were seen in more than half of the patients. Males were significantly more likely to have higher systolic and diastolic BP and higher levels of HDL. Men were also more likely to meet the elevated (systolic) BP criteria for MS.

Table 2.

Metabolic profile (as per IDF criteria) of study sample

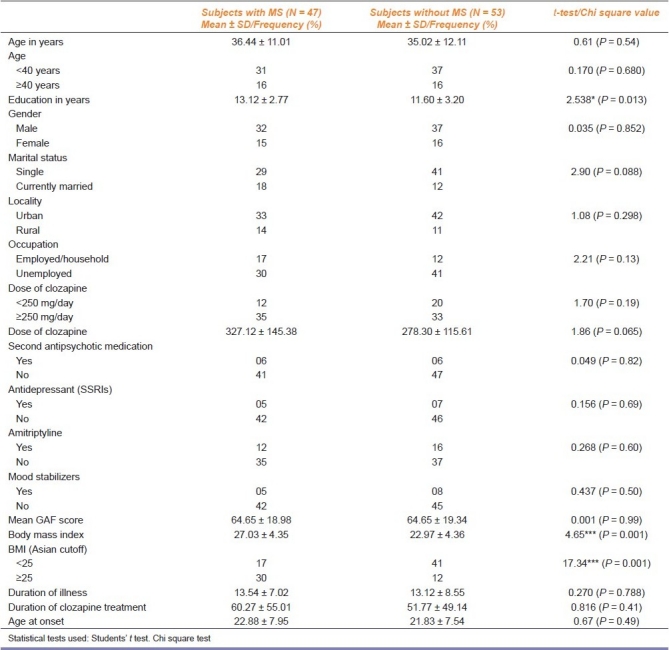

Correlates of Metabolic Syndrome among Patients

Table 3 includes the comparisons carried out between patients with and without MS. Somewhat expectedly patients with MS had significantly higher BMI. The only other significant difference was in educational level; patients with MS had spent more time in school. Logistic regression analysis revealed that these two variables together explained about 19% of the variance in MS (adjusted r2 = 0193; F = 12.8; P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Comparison of subjects receiving clozapine with and without metabolic syndrome

Discussion

Metabolic syndrome was present in 46–47% of the outpatients of this study who were being treated with clozapine. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such study from India which has evaluated MS in patients receiving clozapine, though there are a few Indian estimates of MS in the general population and psychiatrically ill persons. In a study involving 99 schizophrenia subjects, Sahoo et al.,[19] reported prevalence of MS to be 18% after six weeks of antipsychotic treatment. The prevalence of MS (IDF criteria) at six weeks was highest with olanzapine (26%) followed by risperidone (24%) and least with haloperidol (3%). In another study from our centre, involving 92 inpatients, prevalence of MS (IDF criteria) was found to be 38% among patients with different psychiatric disorders and 41% among those with schizophrenia.[20] Thus the prevalence of MS among patients of the current study who were all being treated with clozapine appears to be higher than most such estimates.

There are also a handful of studies across diverse settings that have reported rates of MS with clozapine treatment.[8,13–17] The rate of 46–47% found in the current study was very similar to some of these studies,[8,14,17] although much higher rates (62–64%) have also been found.[15,16]

Some of the variability in rates might be due to the different criteria used, though in the current study rates were similar with two different sets of criteria. The type of patients evaluated (inpatients, outpatients, community patients) could also have contributed to the differences in rates. Finally, other factors such as age, gender, duration of illness, dose and duration of treatment with clozapine, concomitant antipsychotic administration, that have all been linked to higher rates of MS, could also explain the difference in rates. Apart from BMI and educational level, very few correlates of MS with clozapine treatment were found in the current study. Incidentally, BMI has emerged as the most consistent correlate of MS among patients on clozapine.[13] Thus, it has been hypothesized that weight gain contributes most to the development of MS. A direct diabetogenic effect of clozapine has also been suggested, but this association is less certain.[14]

This preliminary study had several methodological problems. Chief among them were its cross-sectional nature and the lack of a healthy control group. Moreover, the absence of prevalence estimates with other antipsychotics meant that it was not possible to estimate the differential risk of MS with clozapine.

Nevertheless, these results along with most of the previous literature on the subject, endorse the notion of MS being highly prevalent among patients on clozapine treatment. Longitudinal investigations of antipsychotic treatment are now required to determine the extent and causes of this complication of clozapine treatment, as well as the measures needed to reduce its impact.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome – a new worldwide definition.A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2005;23:469–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heng D, Ma S, Lee JJM, Tai BC, Mak KH, Hughes K, et al. Modification of the NCEP ATP III definitions of the metabolic syndrome for use in Asians identifies individuals at risk of ischemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer JM, Stahl SM. The metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saari KM, Lindeman SM, Viilo KM, Isohanni MK, Jarvelin MR, Lauren LH, et al. A 4-fold risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: The Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:559–63. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamberti JS, Olson D, Crilly JF, Olivares T, Williams GC, Tu X, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among patients receiving clozapine. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1273–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackin P, Bishop D, Watkinson H, Gallagher P, Ferrier IN. Metabolic disease and cardiovascular risk in people treated with antipsychotics in the community. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:23–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.031716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasnain M, Fredrickson SK, Vieweg WV, Pandurangi AK. Metabolic syndrome associated with schizophrenia and atypical antipsychotics. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:209–16. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor DM, McAskill R. Atypical antipsychotic agents and weight gain - a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:416–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101006416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newcomer JW, Tuomari V, Carson W, L’Italien GJ. Atlanta, Georgia, USA: Poster; American Psychiatric Association; 2005. Diabetes Incidence among patients treated with atypical agents: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan D, Sargeant M, Chukwama J, Hughes G. Audit of metabolic syndrome in adults prescribed Clozapine in community and long stay in-patient. Psychiatr Bull. 2008;32:174–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai YM, Lin CC, Chen JY, Chen TT, Su TP, Chou P. Association of weight gain and metabolic syndrome in patient taking Clozapine: A 8-year cohort study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2010;9(Suppl 1):S132. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05402yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunero S, Lamont S, Fairbrother G. Prevalence and predictors of metabolic syndrome among patients attending an outpatient clozapine clinic in Australia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23:261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Josiassen RC, Filmyer DM, Curtis JL, Shaughnessy RA, Joseph A, Parson RL, et al. An archival, follow-forward exploration of the metabolic syndrome in randomly selected, clozapine-treated patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2009;3:2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed M, Hussain I, O’Brien SM, Dineen B, Griffin D, McDonald C. Prevalence and associations of the metabolic syndrome among patients prescribed clozapine. Ir J MedSci. 2008;177:205–10. doi: 10.1007/s11845-008-0156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahoo S, Ameen S, Akhtar S. Incidence of new onset metabolic syndrome with atypical antipsychotics in first episode schizophrenia: A six week prospective study in Indian female patients. Schizophr Res. 2007;95:247. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahoo S, Manjunatha N, Ameen S, Akhtar S. Metabolic syndrome in first episode schizophrenia-A randomized double-blind controlled, short-term prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattoo SK, Singh SM. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in psychiatric inpatients in a tertiary care centre in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramaniam M, Ng C, Chong SA, Mahendran R, Lambert T, Pek E, et al. Metabolic differences between Asian and Caucasian patients on clozapine treatment.Human Psychopharmacology. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:217–22. doi: 10.1002/hup.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]