Abstract

Background:

Psychotropic drugs have had a remarkable impact in psychiatric practice. However, their utilization in actual clinical practice, effectiveness and safety in real life situation need continuous study.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective cross sectional study was carried out for 6 months. Patients of all ages and both sexes were included in the study while in-patients, referred patients and patients of epilepsy were excluded. Using World Health Organization basic drug indicators, the prescribing pattern was analyzed.

Results:

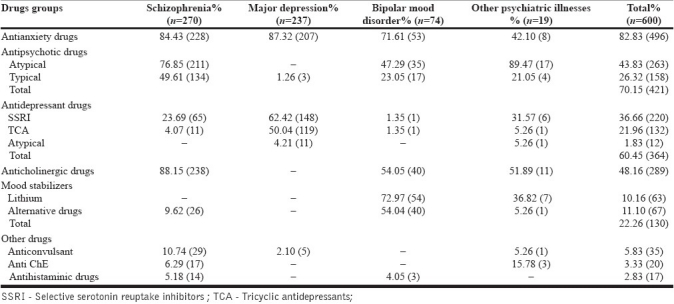

The numbers of psychotropic drugs prescribed per patient were 2.96. Anti-anxiety drugs (82.83%) were most frequently prescribed psychotropic drugs in various psychiatric disorders. Usage of antipsychotic drugs was in 70.15% cases. Atypical antipsychotic drugs (43.83%) were prescribed more frequently than the typical antipsychotic drugs (26.32%). Prescribing frequency of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (36.66%) was more than the tricyclic antidepressant (21.96%) and atypical antidepressant drugs (1.83%) in major depression. Use of mood stabilizers was restricted only to bipolar mood disorders. Central anticholinergic drug was co-prescribed in as many as 88.15% patients receiving antipsychotic drugs.

Conclusion:

Anti-anxiety drug (Benzodiazepine (BZD)) usage was extensive in various psychiatry disorders. Rational use of BZD requires consideration/attention to dose and duration of usage as well as drug interactions with other psychotropic drugs. Routine use of central anticholinergic drug along with atypical antipsychotic drugs also, could not be justified.

Keywords: Drug utilization, prescribed daily dose, psychotropic drugs, prescribing pattern

INTRODUCTION

The rapidly expanding field of psychopharmacology is challenging the traditional concepts of psychiatric treatment and research, and is constantly seeking new and improved drugs to treat psychiatric disorders. In this way, psychiatrists are continuously exposed to newly introduced drugs that are claimed to be safe and more efficacious.[1] Although psychotropic medications have had a remarkable impact on psychiatric practice that legitimately can be called revolutionary, their utilization and consequences on real life effectiveness and safety in actual clinical practice need continuous study.[2]

Drug utilization study has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “The marketing, distribution, prescription and uses of drugs in a society with special emphasis on the resulting medical and social and economical consequences.”[3] The principle aim of the drug utilization research is to facilitate the rational use of the drugs. Without the knowledge of how the drugs are being prescribed, it is difficult to suggest the measures to improve prescribing habits.[4]

Present study was undertaken to analyze the pattern of drug utilization of psychotropic medications in outdoor patients of psychiatry department of a tertiary care teaching hospital in Jamnagar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective cross sectional study of 6 months duration was carried out in outdoor patients (OPD) of the Psychiatry department of Guru Gobind Singh hospital, Jamnagar. Permission of the Institutional Ethical Committee was obtained for conducting the study. Patients of all ages and both sexes were included in the study. In-patients, referred patients, patients of epilepsy as well as those cases where diagnoses were not certain were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained verbally from the patient or legal guardian (when patient was not able to give consent). Patient related information (age, sex, diagnosis) and drug-related information (drugs, dose, dosage form, route of administration) were recorded on a customized data collection sheet. If any clarification was required, the doctors on duty were interviewed. Total 600 cases were analyzed. The WHO drug indicators that were selected to analyze the prescribing pattern included: (1) Average number of the psychotropic drugs prescribed per encounter, (2) Percentage of the psychotropic drugs prescribed by generic name, (3) Percentage of the psychotropic drugs prescribed from essential drug list, (4) Frequency of psychotropic drugs usage as per indication, (5) Average psychotropic drug cost per encounter.

RESULTS

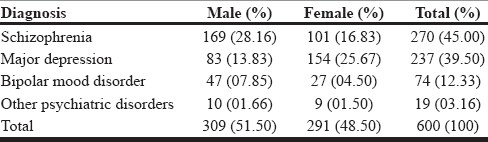

Majority of the psychiatric illnesses (78%) were observed in the age group of 25 to 54 years in both sexes. Out of the total 600 cases surveyed, 51.50% were males and 48.50% were females. Schizophrenia (45%), major depression (39.50%) and bipolar mood disorder (12.33%) accounted for about 97% of total patients. Obsessive compulsive disorders, dementia, postpartum psychosis, social phobia, mental retardation and anxiety disorders accounted for the remaining 3% of the cases [Table 1].

Table 1.

Morbidity pattern and sex difference among different psychiatric illnesses

Total 24 drugs were prescribed in outdoor patients. Among them, 20 drugs were from psychotropic groups. These were anti-anxiety drugs (diazepam, alprazolam and lorazepam decreasing order), antipsychotic drugs (atypical: Risperidone, olanzepine, clozapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone; typical: Haloperidol, trifluoperazine, chlorpromazine), antidepressant drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI): Fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram; tricyclic antidepressants (TCA): Amitryptiline, imipramine; atypical: Mirtazepine) and mood stabilizers (lithium, sodium valproate, carbamazepine). Nine psychotropic drugs out of these 20 were prescribed from 15th WHO essential medicine list. Most frequently prescribed psychotropic medications were the anti-anxiety drugs (82.83%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Use of psychotropic drugs in different psychiatric illnesses

The remaining four drugs prescribed were anticholinergic (trihexyphenidyl), anticonvulsant (clonazepam), antihistaminic (promethazine), and anti-choline esterase (galantamine).

Of the total 24 psychotropic drugs used, 17 were supplied from the hospital and the patients had to purchase the rest of the drugs (lorazepam, olanzepine, escitalopram, aeripiprazole, clonazpeam, sertraline, and clozapine) from outside the hospital. Prescribing frequency of these drugs was only 7.02%. When drugs were not available in the hospital or when patient was not responding to hospital supplied drug then these drugs were prescribed by psychiatrists.

Total number of drug encounters for all 600 patients was 1756. Number of drugs prescribed per patient was 2.96 (range: One to six).

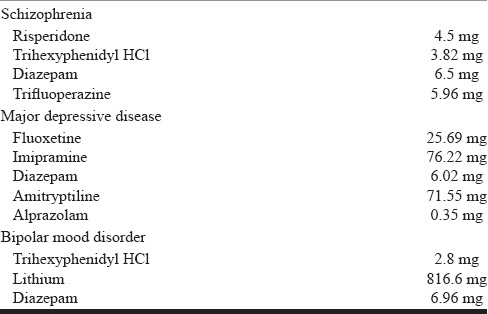

WHO has developed a unit of drug use measurement called defined daily dose (DDD). DDD is the assumed average maintenance dose for a drug used in its main indication in adults. The DDD does not necessarily reflect the recommended or actual dose used. Other way of expressing drug consumption is prescribed daily dose (PDD).[5]

PDD is the average daily dose prescribed as obtained from a representative sample of prescriptions. It is important that diagnosis is linked to the PDD for drugs where the recommended dosage differs from one indication to another (e.g., antipsychotics drugs)[5] [Table 3].

Table 3.

Prescribed daily dose/person/day of the most frequent prescribed drugs in various psychiatric illnesses

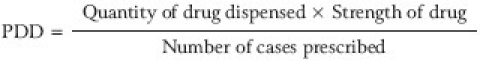

PDD was calculated for the most frequently prescribed drugs in various psychiatric illnesses using the following formula:[6]

DISCUSSION

Patients of schizophrenia and major depression accounted for a large majority (about 85%) of the patients attending the psychiatry OPD in our study. Schizophrenia was more common in males where as prevalence of major depression was 2-fold higher in females [Table 1]. It has been hypothesized that this difference could be due to hormonal influence, effect of childbirth and differing psychosocial stress among the women.[7] Both these disorders were more common in the age group of 35-45 years.

On an average, three drugs were prescribed to the patients of schizophrenia. They all received one typical or atypical antipsychotic drug, one non-neuroleptic drug (mostly anticholinergic), and one antiaxiety drug. Only 23 cases out of 274 were prescribed two antipsychotics and the remaining one drug was prescribed from either of the other two groups. Antipsychotic polypharmacy (two or more antipsychotic drugs together) did not exist. In case of depression, average two drugs were prescribed: One being antidepressant and the other from anti-anxiety group. Fifty cases out of 237 received two antidepressant drugs. Most of the patients of bipolar disorder also received three drugs. Anti-anxiety drug was used in all the patients and the remaining two drugs were either combination of two mood stabilizers (23 cases out of 74) or a mood stabilizer plus an antipsychotic drug (44 cases out of 74).

Anti-anxiety group (BZD) was the most frequently prescribed group of drugs for all psychiatric illnesses. They are remarkably useful and efficacious in a wide range of conditions for short term or intermittent use.[8] However, with long term use the adverse effects (memory impairment, depression, tolerance, dependence) outweigh the benefits, which should be minimized by rational prescribing. Guidelines for the rational use of benzodiazepines recommend their use for short term (maximum four week) or intermittent courses in minimum effective doses, to be prescribed only when symptoms are severe.[9]

Use of antipsychotic drugs (70.15%) was next to the anti-anxiety group (82.83%). Atypical agents were prescribed more frequently (43.83%) than the typical antipsychotics (26.32%). Antipsychotic drugs are the keystones in schizophrenia treatment and since majority of the cases recorded in our study were of schizophrenia, this is expected. Atypical antipsychotic (other than clozapine) are now rated as first-line agents for treatment of mania because their low propensity to cause extra pyramidal side effects (EPS), efficacy against refractory cases and better control over negative symptoms; better tolerance and low relapse rate and safer adverse effect profile.[10] However, some atypical antipsychotic also show dose-related EPS including tardive dyskinesia on long term use, weight gain and hyperprolectinemia. Essential difference between atypical and typical antipsychotic is the size of therapeutic index in relation to acute EPS. Therefore, it has been suggested that therapeutic benefit and adverse effect of antipsychotic drugs can be separated by careful dosing. Typical antipsychotic drugs still play an important role in schizophrenia and offer a valid alternative to atypical where atypical drugs are poorly tolerated or where typical are preferred by patients themselves.[11] Guidelines of National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) of 2009 suggest that there is no longer any imperative to prescribe an “atypical” as first line treatment. Clozapine may be offered only after primary failure of two antipsychotic drugs.[12]

Among the antidepressant drugs, prescribing frequency of SSRI was more than the TCA and atypical agents. SSRI are generally free of sedative effects and safer at higher doses. Better tolerability, combined with their mild adverse effects, accounts for their popularity as most widely prescribed antidepressants.[13] Hence, SSRI are generally recommended as first line pharmacological treatment for depression.[14]

Use of mood stabilizer drugs was restricted only to bipolar mood disorder. The practice followed by the psychiatrists (verbal communication) was that when lithium was not effective or intolerable at 900 mg/day dose, then alternative agent like sodium valproate or carbamazepine was prescribed.

Central anticholinergic drug (trihexyphenidyl) was prescribed in various psychiatric illnesses except in major depression (use was maximum in schizophrenia in 88.15% of cases). Anticholinergic agents are recommended to avoid EPS associated with use of typical (classical) antipsychotics. In schizophrenia, although prescribing frequency of atypical antipsychotic was higher than the typical one, anticholinergic agents were prescribed in majority of patients. One such similar observation was found in a study done by Ren, et al.[15] they have observed that in patients where anticholinergic agents were used concomitantly with atypical antipsychotic, patients tended to stay on the target drug significantly longer than those who did not use any anticholinergic agents. European pharmacoepidemiological study carried out by Broekema et al. also observed that anticholinergic drug was co-administered with atypical antipsychotic drug in schizophrenia. They have observed that atypical antipsychotic therapy alone was not accepted by a substantial number of patients.[16] ‘A study of atypical antipsychotic use for adult outpatients’ by Wheeler A. observed that the anticholinergic drug was used either with atypical antipsychotic or with prescriptions containing both typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs together. However, this study also revealed that co-prescribing of anticholinergic drug may add to new or additive adverse effects (e.g. dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation), which further reduces the quality of life.[17] As routine use of anticholinergic agents add to the complexity, side effects, and expenses, whether they should be prescribe routinely or reserved for the cases of overt EPS remains open to question.

Best practice is to use the minimum effective dose of an antipsychotic drug (typical or atypical). For example, extrapyramidal effects are commonly seen with doses of risperidone higher than 6 mg/day.[18,19] But patients with severe, uncontrollable, or chronic psychiatric illnesses need higher dose. Tarsy, et al.[19] have recommended that there should be certain guidelines regarding the use of antipsychotic drugs to minimize neurological complication associated with their use.

Eighteen cases of extrapyramidal reaction were observed during the study and they were managed by injectable antihistaminic drug (promethazine). Galantamine was prescribed to the patients of schizophrenia (6.29%) and dementia (3.33%).

In our study, PDD of risperidone for schizophrenia was 4.5 mg. EPS are commonly seen with doses of risperidone higher than 6 mg/day. Use of anticholinergic agents in all cases who received risperidone is thus not justified. Use of anticholinergic drugs should be restricted only to the cases where higher dose of risperidone is needed.

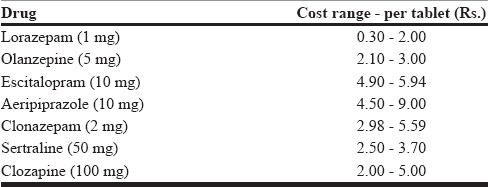

Average cost of psychotropic drugs per encounter for one day was Rs. 2.14 as calculated from hospital supply prices. Cost of different brands of psychotropic drugs (obtained from “Drug today”) available in the market was found to be 3 to 10 times higher than the hospital supply, which is a matter of concern [Table 4].

Table 4.

Cost of the drugs (per tablet) which were prescribed from outside the hospital

CONCLUSION

Prescribing pattern of psychotropic drugs did not differ by gender or age groups. Antis-anxiety drug (BZD) usage was extensive in as they were prescribed in almost all types of psychiatric illnesses. Rational use of BZD requires consideration/attention to dose and duration of usage as well as drug interactions with other psychotropic drugs. In schizophrenia, prescribing frequency of central anticholinergic drug was parallel to those of antipsychotic drugs (total of typical and atypical). Routine use of central anticholinergic drug along with atypical antipsychotic drugs could not be justified. Cost of different brands of psychotropic drugs available in the market was found to be 3 to 10 times higher than the hospital supply. Although some difference in price is expected, the magnitude of difference observed in our study is a matter of concern.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the encouragement, support and valuable suggestions provided by Dr. J. G. Buch for preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.The ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 investigators. Psychotropic drug utilization in Europe: Results from the Europe Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17];Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004 109:55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00331.x. Available from: http://www.iumsp.ch/Enseignement/postgradue/medecine/doc/j.1600-0047.2004.00331.pdf. s . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI. Pharmacotherapy of psychosis and mania. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG, editors. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. pp. 429–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee D, Bergmen U. Studies of utilization. In: Strom BC, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 1st ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1989. pp. 259–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Introduction to Drug Utilization Research by World Health Organization. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17]. Available from: http://www.whocc.no/filearchive/publications/drug_utilization_research.pdf .

- 5.Bakssas I, Lunde PKM. National drug policies: The need for drug utilization studies. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17];Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1986 7:331. Available from: http://medind.nic.in/ibi/t03/i4/ibit03i4p237.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dose intensity. [Last accessed on 2007 Oct 5]. Available from: http://www.umanitoba.ca/centres/mchp/concept/dict/drug/dose_intensity.html .

- 7.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. 9th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry; pp. 534s–78. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heather A. Toxicity and Adverse consequence of Benzodiazepine use. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17];psychiatric Annals. 1995 25:158–165. Available from: http://www.benzo.org.uk/ashtox.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashton H. Guidelines for the rational use of Benzodiazepines. Drugs. 1994;48:25–40. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhasmana DC, Rawat Y, Mishra KC. What is so atypical about atypical antipsychotic? Indian J Pharmacol. 2003;35:322–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oosthuizen P, Emsley RA, Turner J, Keyter N. Determining the optimal dose of haloperidol in first- episode psychosis. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17];J Psychopharmacol. 2001 15:251–5. doi: 10.1177/026988110101500403. Available from: http://jop.sagepub.com/content/15/4/251. abstract . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and clinical Excellence. Schizophrenia: Core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in adults in primary and secondary care. [Last accessed on 2009]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/

- 13.Potter WZ, Hollester LE. Antidepression Agents. In: Katzung BG, editor. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 10th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2007. pp. 475–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and clinical Excellence. Depression (Amended) management of depression in primary and secondary care. [Last accessed on 2007]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk .

- 15.Ren XS, Huang YH, Lee AF, Miller DR, Qian S, Kazis L. Adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotic and anticholinergic drugs among patients with schizophrenia. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17];J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005 30:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2004.00610.x. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15659005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broekema WJ, Groot IW, Vanharten PN. Simultaneous prescribing of atypical antipsychotics, conventional antipsychotic and anticholinergic- a European study. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17];Pharma World Sci. 2007 29:126–30. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9063-1. Available from: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/klu/phar/2007/00000029/00000003/00009063 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheeler A. Atypical antipsychotic use for adult outpatients in New Zealand's Auckland and Netherland regions. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 17];J N Z Med Assoc. 2006 119:1237. Available from: http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/119-1237/2055/content.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bash ES, Mayer SE. 5 Hydroxytryptamine receptor agonist and antagonist. In: Bruton LL, Lazo JL, Parker KL, editors. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. pp. 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarsy D, Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI. Effects of newer antipsychotics on extrapyramidal function. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:23–45. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]