Abstract

Children with ADHD typically experience significant impairment at home and school, and their relationships with parents, teachers, and peers often are strained. Psychosocial interventions for ADHD generally focus on behavior change in one environment at a time (i.e., either home or school); however, unisystemic interventions generally are not sufficient. The purpose of this article is to describe a family–school intervention for children with ADHD. In addition, program strategies and theoretical bases are discussed.

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) affects approximately 3% to 10% of children in the United States (Brown et al., 2001). Children with ADHD frequently evidence home- and school-related problems, including disruptive classroom behavior, decreased accuracy on assignments, problems with study skills, difficulty in social interactions, and difficulty following parent and teacher directions, all of which may result in significant impairment at home, school, and in the community (see Barkley, 2006, and DuPaul & Stoner, 2003, for more information about ADHD). Given the incidence of the disorder and the significant impairment experienced by children diagnosed with this disorder, ADHD is recognized as a major public health concern (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001).

Children with ADHD are clearly at risk for early school failure (Kern et al., 2007). Although the symptoms of ADHD directly contribute to academic and peer relationship deficits, risk factors in the family environment indirectly contribute to their lack of preparedness to perform competently in school. Children with ADHD tend to have stressful and conflictual interactions with their parents, which makes it difficult for them to establish and maintain strong parent–child attachments (Barkley, 2006). In turn, failure to establish strong attachments with caregivers may contribute to self-regulation deficits (Pianta, 1997). These deficits may result in difficulty developing strong relationships with adults and peers in school, which can lead to educational impairments (Pianta & Walsh, 1996). Also, children who have difficulties with self-regulation often display lower levels of academic engagement and motivation than students without these difficulties, which also negatively impacts academic outcomes (Volpe et al., 2006).

In addition, families of children with ADHD may have more difficulty supporting their children’s education than other families (Rogers, Wiener, Marton, & Tannock, 2009). Structuring the home environment so that it promotes education may be difficult for these families, due to conflictual parent–child relationships and non-compliant child behavior. Also, parent–teacher relationships may be adversarial as a result of frequent complaints by educators that the children are uncooperative and disruptive.

In school, children with ADHD frequently are not engaged in school work and demonstrate high rates of disruptive behavior. The attention and behavior problems of these children may strain the teacher–student relationship and interfere with the learning of others. The typical classwide interventions generally are not sufficient to address the needs of these children; specialized intervention approaches are typically required (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). Treatment plans for ADHD often include stimulant medication and psychosocial interventions targeting academic and/or behavioral difficulties. Most psychosocial interventions are unisystemic; that is, the intervention targets home or school functioning separately. School-based interventions, such as environmental modifications, reinforcement systems, computer-assisted instruction, and peer tutoring can have beneficial effects on children’s academic performance and school behavior (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). Likewise, family-based strategies such as parent training, which focuses on changing child behavior at home and improving parent–child interactions, can have beneficial effects on behavior at home and in the community (e.g., Barkley, Edwards, Laneri, Fletcher, & Metevia, 2001; Webster-Stratton, 2005a). Although these strategies are effective, school- or family-based interventions administered separately generally are not sufficient. For example, unisystemic approaches do not fully address family factors that are related to school success. Research strongly suggests that the optimal approach to psychosocial intervention for ADHD is one that links families and schools to address target problem behaviors and build competencies.

Family School Success (FSS) is an intervention program that links the family and school systems to address the needs of elementary school children with ADHD (Power, Soffer, Clarke, & Mautone, 2006). In addition, the health system may be included in the process of intervention planning for cases in which the parents elect to have their children take medication to treat ADHD as part of the intervention package. The purpose of this article is to describe key components of the program and the theoretical foundation upon which they were developed.

FSS Strategies to Promote Home and School Functioning

FSS was originally designed as a clinic-based, family–school intervention for elementary-aged children with ADHD. The FSS program is grounded in attachment theory, social learning theory, and ecological systems theory. In addition, research related to family involvement in education strongly influences the FSS model. FSS consists of 12 weekly sessions, including six group sessions for parents with concurrent child groups, four individual family behavior therapy sessions, and two conjoint behavioral consultation sessions held at the school (Power et al., 2006). Program goals include (a) strengthening the parent-child relationship; (b) improving parents’ behavior management skills (i.e., through the use of positive attending and token economy systems); (c) increasing family involvement in education at home (i.e., through homework support and parent tutoring); and (d) promoting family–school collaboration to address educational difficulties. Program clinicians have been doctoral-level providers in clinical or school psychology.

Strengthening the Parent–Child Relationship

As is the case for several parent training programs for children with attention and behavior disorders (e.g., Barkley et al., 2001; Bell & Eyberg, 2002; McMahon & Forehand, 2003; Webster-Stratton, 2005a), the FSS program draws from attachment theory and places a strong emphasis on the development and maintenance of strong parent–child relationships. Through positive interactions with their parents, children learn self-regulation skills that provide the foundation for relationships with adults and peers outside of the home.

Very early in the FSS program, participants learn the value of positive attending in strengthening the parent–child relationship and promoting behavior change. Children with ADHD frequently receive negative feedback from adults due to inappropriate behavior at home, at school, and in the community, which can have a negative impact on the adult–child relationship. As parents learn how to utilize positive attending more regularly, interactions between parents and children become less strained.

In addition to positive attending, effective strategies have been developed for strengthening parent–child relationships. For example, the Child’s Game (McMahon & Forehand, 2003), Child-Directed Interaction training (Eyberg, Schuhmann, & Rey, 1998), and child-centered play (Webster-Stratton, 2005a) are highly useful and effective approaches that have been incorporated into many family behavior therapy programs. All these approaches provide guidance to parents on playing with their children in an attentive, responsive, nondirective manner. Families participating in FSS learn strategies for child-focused play as another method of strengthening the parent–child relationship.

Improving Parents’ Behavior Management Skills

Parents participating in FSS are presented with a combination of empirically supported behavioral interventions to improve child self-regulation. These strategies are rooted in social learning theory and emphasize the importance of modifying the antecedents and consequences in the environment to shape child behavior. Many empirically supported programs include components such as (a) setting consistent rules and giving instructions in a clear and consistent manner, (b) providing positive reinforcement for appropriate behavior, and (c) using effective and strategic punishment strategies (e.g., Forehand & Long, 2002).

A primary goal of FSS and other behavioral interventions is to increase the rate at which parents use attention as a positive reinforcer for appropriate behavior and withdraw attention in response to inappropriate behavior (i.e., differential attention). The FSS program helps parents understand that attention can increase the likelihood of a desired behavior and that ignoring undesired behaviors may make them occur less frequently. In FSS, parents are trained to deliver positive reinforcement immediately following appropriate behavior in a targeted, strategic manner.

Another example of positive reinforcement used in FSS is the token economy. The basic premise of a token economy is that tokens are frequently provided to the target child, contingent upon the occurrence of appropriate behavior, and can be exchanged at a later time for valued reinforcers (see Barkley, 1997). Parents are taught to design an efficient, effective system of reinforcement and are encouraged to use it consistently. Token economies can be difficult to design and implement, so it is important that the therapist is well versed in behavioral theory and works closely with the parent when developing the system.

Punishment strategies are meant to decrease the frequency of inappropriate behaviors and are typically introduced after positive reinforcement in an effort to build the parent–child relationship first. Therefore, in FSS as in other behavioral parent training programs, parents are instructed to apply punishment in a targeted manner while continuing to use positive reinforcement. Parents first learn to give corrective feedback calmly, consistently, and effectively. Next, parents learn response-cost, a strategy in which privileges or tokens are removed as a consequence for undesirable behavior (Barkley, 1997). Time out is a commonly used form of response cost involving the withdrawal of positive reinforcement as a consequence for inappropriate behavior (Webster-Stratton, 2005b). When training parents in the use of punishment strategies, FSS clinicians emphasize the importance of providing positive reinforcement to children at least four times more frequently than punishment.

Increasing Family Involvement in Education

Family involvement in education is associated with children’s school engagement, attitudes toward school, and academic performance (Christenson & Sheridan, 2001; Epstein, 1995). Researchers have identified three fundamental ways in which families can be involved in education: (a) involvement in the home, such as making education a priority, setting aside time for literacy activities, and limiting television viewing; (b) collaboration between family and school, such as conferencing with teachers to resolve issues that may be interfering with the child’s education; and (c) involvement in the school, such as participating in the parent–teacher organization or volunteering to be a class aide (Epstein, 1995; Fantuzzo, Tighe & Childs, 2000). Family involvement in education at home and family–school collaboration appear to be the most effective ways for parents to promote their children’s success in school.

Promoting family involvement in education at home

Home-based involvement in educational activities, including supervision of homework and studying, can be challenging for parents of children with ADHD. Children with ADHD frequently have difficulty with homework completion and often attempt to avoid study sessions or educational activities. As a result, families often require specialized training related to establishing the home learning environment and a homework and study routine. FSS incorporates strategies that have been developed to improve family involvement in educational activities and to help parents establish the curriculum of the home (Walberg, 1984). For example, parents can consistently communicate the value of education to their children and establish a home environment that supports learning (i.e., by limiting TV and video game time and providing educational games and materials; Christenson & Sheridan, 2001; Webster-Stratton, 2005b). Also, parents can increase child involvement in literacy activities (Taverne & Sheridan, 1995), provide parent tutoring (Hook & DuPaul, 1999), and utilize strategies to improve homework performance (Power, Karustis, & Habboushe, 2001).

FSS offers two specific strategies to enable parents to assist their children with homework and studying: goal setting and parent tutoring (Power et al., 2001). An initial step in goal setting is chunking homework assignments into smaller, more manageable subunits. This strategy can help children feel less overwhelmed with homework assignments, allow them to have success and receive positive reinforcement frequently, and may reduce the argumentativeness that often accompanies homework. The parent is taught to work with the child to set reasonable goals for work completion and accuracy within a specified period of time. At the completion of each subunit of work, the parent and child jointly determine whether or not goals have been met, and the child is reinforced for goal attainment (e.g., verbal praise, tokens embedded in a token economy).

Parents may help their children develop study skills through parent tutoring sessions designed to assist children in learning material and preparing for tests. The drill sandwich or folding-in technique is a parent tutoring strategy based on research indicating that children learn best when most information presented to them is already known (Shapiro, 2004). When teaching parents how to most effectively study with their children, it is important to emphasize that the child should already know between 70% and 80% of the material, with only 20% to 30% new or unknown material. This strategy ensures that children experience high rates of success, which promotes engagement in learning activities.

Promoting family–school collaboration

Ecological/systems theory asserts that multiple systems, and relationships between systems, contribute to child development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Pianta & Walsh, 1996). Specifically, consistency between home and school and productive parent–teacher collaborations have been shown to be associated with enhanced academic, social, and emotional outcomes for children (Kohl, Lengua, McMahon, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2000; Minke, 2006). The FSS program promotes family–school collaboration through the use of Conjoint Behavioral Consultation (CBC). The CBC model (Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2008) proposes that by working together, parents and teachers can better address the child’s educational and behavioral needs. This model includes four steps: (a) conjoint problem identification, (b) conjoint problem analysis, (c) intervention implementation, and (d) conjoint intervention evaluation. At each step, parents and teachers work closely together to develop and implement strategies to improve student performance and behavior.

The FSS program includes two family–school CBC sessions to assist parents and teachers in identifying child strengths and needs, as well as resources and limitations in the home and school environments. During the first session, the parents and teacher discuss the child’s homework performance and classroom behavior. The team collaboratively determines whether the child has a consistent method of recording homework assignments and whether the difficulty level of assignments is matched to the child’s skill level. In addition, the teacher is asked to identify the amount of time the average student in the class should spend on homework assignments. If any of these are an area of difficulty for the child, the team develops strategies to address the problem. During the second CBC session, which is conducted toward the end of the family’s involvement in the FSS program, the team evaluates the child’s progress and adjusts intervention strategies as necessary. In addition, the FSS clinician encourages the family and school staff to continue working together to collaboratively support the child as he or she progresses through school.

Also, the daily report card (DRC) is a specific intervention that is used in the context of CBC. The DRC involves the parent providing reinforcement at home for performance on targeted behaviors during the school day (Kelley, 1990). The parent and teacher jointly develop the DRC by engaging in a conversation about target behaviors, the scale on which the child will be evaluated, and the frequency with which the child will receive feedback. At the end of the school day, the child presents the DRC to his or her parents and the agreed-upon reinforcer is administered if the child has reached a specified goal. This provides additional opportunities for the child to earn positive reinforcement and can serve as documentation of the child’s progress on targeted behaviors. (For a list of resources pertaining to each FSS strategy, see Table 1.)

Table 1.

Resources for Practitioners

| Intervention Target | Strategy | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strengthening the parent–child relationship and changing behavior | Child-directed play, token economy | Bell and Eyberg (2002), Webster-Stratton (2005b) |

| Applying punishment effectively | Parent-directed interactions, response cost | Bell and Eyberg (2002), Webster-Stratton (2005b) |

| Improving family-school collaboration/problem solving | Conjoint behavioral consultation | Sheridan and Kratochwill (2008) |

| Supporting children with homework | Goal setting and contingency contracting, environmental modifications | Power, Karustis, and Habboushe (2001) |

| Improving study skills | Drill sandwich or “folding in” technique | Shapiro (2004) |

| Changing school behavior | Daily report card | Kelley (1990) |

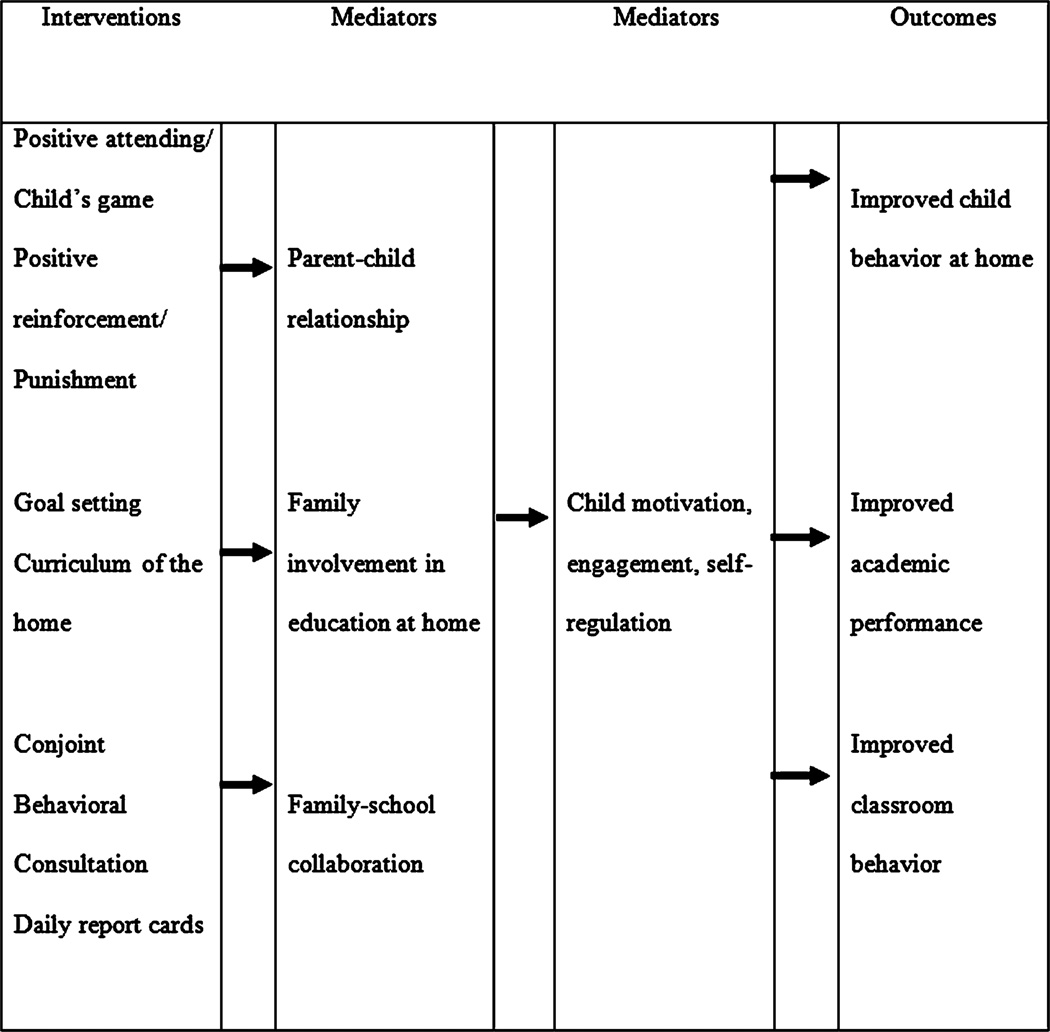

Figure 1 illustrates the theory of change for the FSS intervention. FSS targets three processes—the parent–child relationship, family involvement in education at home, and family–school collaboration—using strategies based upon attachment theory, social learning theory, and ecological/systems theory. Changes in these processes are likely to enhance child motivation, engagement, and self-regulation, resulting in improvements in child behavior at home, academic performance, and student behavior in school.

Figure 1.

Theory of Change for the Family School Success (FSS) Program. The intervention components of FSS were designed to target three processes; which are hypothesized to improve child motivation, engagement, and self-regulation; thus leading to improvements in child outcomes.

Working With Challenging Families and Teachers

As in any intervention program, clinicians may experience challenges when interacting with some parents and teachers. The family–school relationship may be strained prior to family and teacher involvement in the program, so such cases might require additional efforts on the part of the clinician prior to conducting conjoint consultation sessions. For example, the clinician might spend time working with the family and teacher individually to prepare each party to work collaboratively before the conjoint consultation session is scheduled. When preparing families to work with the teacher, the clinician assists families in recognizing that the child may be exhibiting behavior in class that has resulted in considerable stress for the teacher. The family and clinician review the teacher’s prior efforts to work with the child, and the family learns how to affirm those efforts during the family–school meeting. When preparing teachers to work with the family, the clinician describes how the family has been involved in the program, emphasizing that the family recognizes how challenging the child’s behavior can be.

It is possible that some parents and teachers will be resistant to change for a variety of reasons, so they may have a difficult time implementing strategies that require significant planning, consistency, and motivation. In working with these individuals, it is important to remember that change is a process that happens in stages (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984). Although some parents and teachers at the outset of intervention may be motivated and ready to invest in behavioral change, others may be ambivalent or have other priorities to address. For parents and teachers who are not ready to make a commitment to a program such as FSS, strategies included in motivational interviewing may be effective (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). These strategies might include offering empathy, eliciting statements that reflect a willingness to change, and reinforcing efforts to initiate change.

Conclusions

Most approaches to psychosocial intervention for children with ADHD are unisystemic, focusing on either the family or school. Optimizing the effects of intervention typically involves a multisystemic approach that targets both the family and school. FSS is an intervention for children with ADHD designed to promote child development in the family and school. This program focuses on strengthening the parent–child relationship, promoting family involvement in education at home, and fostering family–school collaboration using a variety of strategies based upon attachment, social learning, and ecological/systems theories. Although intervention programs for children with ADHD that include a focus on both home and school are beginning to emerge, FSS is unique in its emphasis on strengthening relationships while building academic and social skills.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant R01MH0682 90 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Department of Education, and by R34 MH0 80782 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Mautone, psychologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Elizabeth K. Lefler, post-doctoral fellow at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia at the time the manuscript was prepared. She currently is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Northern Iowa

Thomas J. Power, program director for the Center for Management of ADHD at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: Treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1033–1044. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Defiant children: A clinician’s manual for assessment and parent training. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Edwards G, Laneri M, Fletcher K, Metevia L. The efficacy of problem-solving communication training alone, behavior management training alone, and their combination for parent–adolescent conflict in teenagers with ADHD and ODD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:926–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SK, Eyberg SM. Parent–child interaction therapy: A dyadic intervention for the treatment of young children with conduct problems. In: VandeCreek L, Jackson TL, editors. Innovations in clinical practice: Vol. 20. A source book. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange; 2002. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Freeman WS, Perrin JM, Stein MT, Amler RW, Feldman HM, et al. Prevalence and assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in primary care settings. Pediatrics. 2001;107:e43–e54. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson SL, Sheridan SM. Schools and families: Creating essential connections for learning. New York: Guilford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Stoner G. ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL. School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan. 1995;76:701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Schuhmann EM, Rey J. Child and adolescent psychotherapy research: Developmental issues. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:71–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1022686823936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Tighe E, Childs S. Family Involvement Questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Long N. Parenting the strong-willed child (Revised) Chicago: Contemporary Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hook CL, DuPaul GJ. Parent tutoring for students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Effects on reading performance at home and school. School Psychology Review. 1999;28:60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML. School-home notes: Promoting children’s classroom success. New York: Guilford; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kern L, DuPaul GJ, Volpe RJ, Sokol NG, Lutz JG, Arbolino LA, et al. Multisetting assessement-based intervention for young children at-risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Initial effects on academic and behavioral functioning. School Psychology Review. 2007;36:237–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, McMahon RJ Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Parent involvement in school: Conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:501–524. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Forehand RL. Helping the noncompliant child: Family-based treatment for oppositional behavior. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Minke KM. Parent–teacher relationships. In: Bear GG, Minke KM, editors. Children’s needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists; 2006. pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Adult–child relationship processes and early schooling. Early Education and Development. 1997;8:11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Walsh DB. High-risk children in schools: Constructing sustaining relationships. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Karustis JL, Habboushe D. Homework success for children with ADHD: A family–school intervention program. New York: Guilford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Soffer SL, Clarke AT, Mautone JA. Multisystemic intervention for children with ADHD. Report on Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in Youth. 2006;6:51–52. 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The transtheoretical approach: Crossing the traditional boundaries of therapy. Malabar, FL: Krieger; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Wiener J, Marton I, Tannock R. Parental involvement in children’s learning: Comparing parents of children with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Journal of School Psychology. 2009;47:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro ES. Academic skills problems workbook. Revised ed. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan SM, Kratochwill TR. Conjoint behavioral consultation: Promoting family–school connections and interventions. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Taverne A, Sheridan SM. Parent training in interactive book reading: An investigation of its effects with families at risk. School Psychology Quarterly. 1995;10:41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe RJ, DuPaul GJ, DiPerna JC, Jitendra AK, Lutz JG, Tresco K, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and scholastic achievement: A model of mediation via academic enablers. School Psychology Review. 2006;35:47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Walberg HJ. Families as partners in educational productivity. Phi Delta Kappan. 1984;65:397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. The incredible years: A training series for the prevention and treatment of conduct problems in young children. In: Hibbs E, Jensen P, editors. Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005a. pp. 507–555. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. The incredible years: A trouble-shooting guide for parents of children aged 2–8 years. Seattle, WA: Incredible Years; 2005b. [Google Scholar]