Background: Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates nuclear translocation of proapoptotic protein kinase C delta (PKCδ).

Results: Tyrosine phosphorylation causes a conformational change that exposes the nuclear localization sequence, allowing binding of importin-α.

Conclusion: Nuclear localization of PKCδ is regulated by access of importin-α to the nuclear localization sequence.

Significance: Nuclear import of PKCδ, which induces apoptosis, is tightly regulated so as to prevent inappropriate cell death.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Nuclear Translocation, Phosphotyrosine, Protein Kinase C (PKC), Protein Phosphorylation, Signal Transduction

Abstract

PKCδ translocates into the nucleus in response to apoptotic agents and functions as a potent cell death signal. Cytoplasmic retention of PKCδ and its transport into the nucleus are essential for cell homeostasis, but how these processes are regulated is poorly understood. We show that PKCδ resides in the cytoplasm in a conformation that precludes binding of importin-α. A structural model of PKCδ in the inactive state suggests that the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) is prevented from binding to importin-α through intramolecular contacts between the C2 and catalytic domains. We have previously shown that PKCδ is phosphorylated on specific tyrosine residues in response to apoptotic agents. Here, we show that phosphorylation of PKCδ at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 results in a conformational change that allows exposure of the NLS and binding of importin-α. In addition, Hsp90 binds to PKCδ with similar kinetics as importin-α and is required for the interaction of importin-α with the NLS. Finally, we elucidate a role for a conserved PPxxP motif, which overlaps the NLS, in nuclear exclusion of PKCδ. Mutagenesis of the conserved prolines to alanines enhanced importin-α binding to PKCδ and induced its nuclear import in resting cells. Thus, the PPxxP motif is important for maintaining a conformation that facilitates cytosplasmic retention of PKCδ. Taken together, this study establishes a novel mechanism that retains PKCδ in the cytoplasm of resting cells and regulates its nuclear import in response to apoptotic stimuli.

Introduction

PKCδ is a ubiquitously expressed member of the PKC family of lipid-regulated kinases that has been implicated in diverse biological functions, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, immunity, and apoptosis (1–10). Mice deficient for PKCδ (δKO) develop normally, but with age develop systemic autoimmune disease associated with hyperproliferation of B cells, suggesting that PKCδ is important for the establishment of B-cell tolerance (2, 4). Work from our lab and others has defined PKCδ as a critical regulator of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway both in vivo and in vitro (11–16). In addition, studies in δKO mice show that loss of PKCδ protects against γ-irradiation-induced apoptosis, suggesting that PKCδ is required for proper induction of apoptosis in epithelial cells (9). Furthermore, we have recently shown that PKCδ promotes proliferation and functions as a tumor promoter in lung cancer. The tumor promoter activity of PKCδ appears to be largely due to its ability to regulate survival signaling pathways (17).

The ability of PKCδ to regulate such diverse cellular functions as apoptosis and proliferation is dictated in part by tight regulation of its subcellular localization (18–20). Inappropriate targeting of PKCδ is associated with tumor progression in bladder and endometrial cancer and with the development of autoimmune disease in mouse models (21, 22). We have previously shown that PKCδ translocates to the nucleus in response to apoptotic signals, and that nuclear accumulation of PKCδ is necessary and sufficient for induction of apoptosis (23, 24). This suggests that conversely, the cytoplasmic retention of PKCδ may be essential for cell survival. Proteins that are >40 kDa must be actively transported through the nuclear pore complex. Most protein transport through the nuclear pore complex is facilitated through binding of importins to a nuclear localization sequence (NLS)3 found on cargo proteins (25). Our lab has previously identified a bipartite NLS in the catalytic domain of PKCδ, and we have shown that mutations of specific residues in this NLS abolish the nuclear localization of PKCδ in response to apoptotic signals (23). However, in resting cells, PKCδ is predominantly localized to the cytoplasm, suggesting that additional regulatory steps may be involved in mediating nuclear import of this kinase. Notably, tyrosine phosphorylation at specific residues in the regulatory domain of PKCδ, and caspase cleavage of PKCδ in the hinge region are permissive for nuclear import, suggesting that the regulatory domain of PKCδ plays a role in its cytoplasmic retention (9, 23, 24). How these events are coordinated to facilitate nuclear import of PKCδ in response to apoptotic signals is not known. In the current studies, we show that translocation of PKCδ from the cytoplasm into the nucleus is regulated by access of importin-α to the NLS. Our studies indicate that nuclear translocation of PKCδ involves a series of specific and coordinated events, thus assuring tight control of the apoptotic response.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfection

The ParC5 cell line was cultured as described previously (26). 293T cells were cultured in DMEM/high glucose medium (Thermo Scientific, SH30243.02) with 10% FBS (Sigma, F2442). COS-7 cells were cultured in DMEM/high glucose medium (Thermo Scientific, SH30022.01) with 10% FBS. Cells were transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science, 11988387001), following the manufacturer's protocol. Primary mouse parotid cells were isolated as described previously from wild type or PKCδ knock-out C57Bl/6 mice that were a gift of Dr. K. Nakayama (2, 27).

Plasmids and Site-directed Mutagenesis Primers

The cloning of mouse PKCδ into the mammalian expression vector pCDNA3 was described previously (23). The rat N terminus GFP-tagged PKCδ was a generous gift from Dr. Peter Parker (London Research Institute, London, UK). The Y64F, Y155F, and Y64F/Y155F mutants were generated in the background of the mouse C terminus GFP-tagged PKCδ as described previously (27). The Y64D/Y155D, PAxxA, and AAxxA mutants were generated in the background of the rat N terminus GFP-tagged PKCδ using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, 200518-5) with the following primers from Integrated DNA Technologies: Y64D/Y155D, 5′-TCAACATTCGACGCCCACATC and 5′-ATTAAACAGGCCAAGATTCAC; PAxxA, 5′-AAGGTGGAGCCGGCCTTTAAGG CCAAAGTGAAA; and AAxxA, 5′-AAGGTGGAGG CGGCCTTTAAGGCCAAAGTGAAA. GFP2-NLS was generated as described previously (23). The various GFP2-PPxxP mutants were generated in the background of GFP2-NLS using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit with the following primers: AAxxA, 5′-AAGGTGGAG GCGGCCTTTAAGGCCAAAGTGAAA; PAxxA, 5′-AAGGTGGAGCCGGCCTTTAAGGCCAAAG TGAAA; APxxP, 5′-AAGGTGGAGGCGCCCTT TAAGCCCAAAGTGAAA; PAxxP, 5′-AAGGTG GAGCCGGCCTTTAAGCCCAAAGTGAAA; PPxxA, AAGGTGGAGCCGCCCTTTAAGGCC AAAGTGAAA; APxxA, 5′-AAGGTGGAGGCGC CCTTTAAGGCCAAAGTGAAA; and AAxxP, 5′-AA GGTGGAGGCGGCCTTTAAGCCCAAAGTGAAA.

Immunofluorescent Microscopy

ParC5 cells were grown on glass coverslips and transfected with the indicated DNA constructs. 18 h following transfection, cells were either left untreated or were treated with 5 mm H2O2 (Sigma, H1009) for 1 h. Immediately following treatment, cells were rinsed once with PBS and were air-dried. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min followed by three 15-min washes with PBS. Coverslips containing fixed cells were mounted on slides using Vectashield with DAPI mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, H-1200). Subcellular localization of GFP-PKCδ proteins was analyzed by fluorescent microscopy. Nuclear localization was quantified as the number of cells with predominantly nuclear localized GFP over the total number of GFP positive cells per field. More than 250 cells were counted for each variable per experiment.

Subcellular Fractionation

293T cells were transfected with the indicated DNA constructs. 18 h following transfection cells were harvested, and whole cell lysate (WCL) or nuclear fractions were prepared. Nuclear fractions were isolated using a nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit (BioVision, Inc., K266-100) according to the manufacturer's protocol except that Triton X-100 was added to the nuclear extraction buffer at a final concentration of 1%. Protein concentration was determined using the DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, 500-0111). Nuclear fractions and WCL were resolved on SDS-PAGE, and Western blots were probed with the following antibodies: anti-GFP (Invitrogen, 33-2600); anti-human PKCδ C-20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-937); and anti-lamin B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-6217).

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blots

293T or ParC5 cells were transfected with the indicated pGFP-PKCδ constructs. 18 h following transfection, cells were either left untreated or were treated with 1 mm H2O2, 5 mm H2O2 or 200 μm etoposide (Sigma, E1383) as indicated. For some experiments, cells were treated with 1 μm 17-AAG (A.G. Scientific, Inc, A-1298) for 3 h, or 10 μm Celastrol (Cayman Chemical, 70950) for 30 min. Immediately following treatment, cells were lysed with buffer A ((50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mm NaF, 10 mm Na4P2O7, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche Applied Science, 11697498001), and 1× phosphatase inhibitor mixture tablets (Roche Applied Science, 04906837001)). Total protein (0.5 mg) was mixed with anti-GFP antibody (Abcam, ab290) for 3 h at 4 °C and an additional 1 h with protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma, P6649). The immunocomplexes were then subjected to five 5-min washes with buffer A before they were separated by SDS-PAGE. The immunoblots were probed with the following antibodies: anti-importin-α (BD Transduction Laboratories, 610486); anti-Hsp90 (BD Transduction Laboratories, 610419) 4G10 pan anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (Millipore, 16-316), δanti-phospho-PKCδ (Tyr-64) (Assay Biotech), anti-phospho-PKCδ (Tyr-155) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-23770-R). Approximately 1% of the immunocomplexes were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblots were probed with anti-GFP antibody (Invitrogen, 33-2600). 10 μg of WCL was separated on SDS-PAGE, and the immunoblots were probed with anti-importin-α or anti-Hsp90 antibodies. Densitometric analysis was performed using Launch VisionWorksLS analysis software.

PKC Kinase Assay

ParC5 or COS-7 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs. 18 h following transfection cells were either left untreated or were treated with 5 mm H2O2 for 30 min. Cells were lysed with JNK lysis buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.7, 20 mm β-glycerophosphate, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.3 m NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm DTT, 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche Applied Science, 11697498001), and 1× phosphatase Inhibitor Mixture (Roche Applied Science, 04906837001)). The GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated as described above, and the immunocomplexes were washed at least three times with JNK lysis buffer. Kinase assays were performed using the PepTag® Non-Radioactive Protein Kinase C assay system (Promega Corp., V5330), following the manufacturer's protocol, except no lipid activator was added. Kinase activity was calculated as the phosphorylated/non-phosphorylated substrate ratio, normalized to the amount of GFP-tagged protein that was immunoprecipitated, and expressed as relative units.

TUNEL Assay

Primary mouse parotid cells were transduced with the indicated adenoviruses as described previously (27). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling was performed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection TMR Red kit (Roche Applied Science, 12156792910) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were stained with 5 μg/ml DAPI (Sigma, D9564) to visualize the nucleus. Cells expressing the GFP fusion proteins were visualized by immunofluorescent microscopy and counted using a 40× objective. For cells expressing GFP-PKCδ proteins, GFP-positive, TUNEL-positive (TMR Red fluor) cells exhibiting chromatin condensation were scored as apoptotic; > 400 cells were counted for each variable per experiment. For cells not expressing GFP-PKCδ proteins, TUNEL-positive (TMR Red fluor) cells exhibiting chromatin condensation were scored as apoptotic.

RESULTS

Regulated Binding of Importin-α to PKCδ in Response to Apoptotic Agents

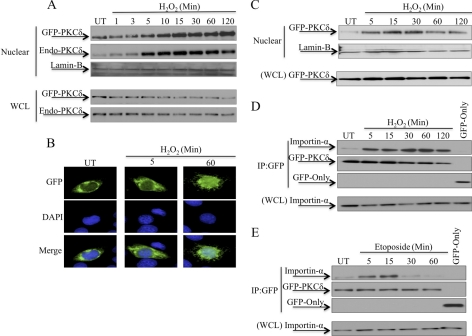

Work from our lab and others have shown that PKCδ translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in response to apoptotic stimuli such as etoposide (23, 24). In the experiment shown in Fig. 1A, ParC5 cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ and treated with H2O2 for the indicated times. H2O2 induced nuclear import of PKCδ as early as 5 min following treatment, with maximal accumulation in the nucleus at 15 min. Endogenous PKCδ translocated into the nucleus with identical kinetics as that of the ectopically expressed protein (Fig. 1A). PKCδ was imported into the nucleus with similar kinetics in 293T cells transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ and treated with H2O2 (Fig. 1C). Fig. 1B shows fluorescent imaging of nuclear PKCδ in ParC5 cells transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ and treated with H2O2.

FIGURE 1.

Regulated binding of importin-α to PKCδ in response to apoptotic agents. A and B, ParC5 cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ and were either left untreated (UT) or treated with 5 mm H2O2. A, nuclear fractions and WCL were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblots were probed with an anti-PKCδ antibody to show endogenous and ectopically expressed proteins. Lamin-B was used as a loading control for nuclear fractions. B, cells were fixed and GFP or DAPI fluorescence was analyzed with fluorescence microscopy. Shown are GFP (top), DAPI (middle), and merged (bottom); representative images were taken at 40× magnification. C, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ and were either left untreated or treated with 5 mm H2O2. Nuclear fractions and WCL were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblots were probed with an anti-GFP antibody. Lamin-B was used as a loading control for nuclear fractions. D and E, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ or pGFP and were either left untreated or treated with 5 mm H2O2 (D) or 200 μm etoposide (E). Upper panels, GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from WCL using an anti-GFP antibody and assayed by Western blot for endogenous importin-α interaction or for the amount of GFP-tagged protein immunoprecipitated (IP). Lower panels, Western blot of WCL to show the amount of importin-α present in the lysates. For all panels, each experiment was repeated three or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

Transport through the nuclear pore complex is mediated by a family of nuclear transport receptors that recognize and bind to the NLS on cargo proteins, the most common of which are members of the importin family (25, 28–32). In resting cells, PKCδ could be retained in the cytoplasm bound to importin-α awaiting an apoptotic signal, or the interaction of PKCδ with importin-α could be induced by apoptotic signals. To address these possibilities, we analyzed the association of PKCδ and importin-α by co-immunoprecipitation in cells treated with H2O2 or etoposide. As shown in Fig. 1D, a small amount of PKCδ associates with importin-α in untreated cells, consistent with the basal level of PKCδ typically found in the nucleus under resting conditions (Fig. 1A). However, the association of importin-α with PKCδ dramatically increased as early as 5 min after treatment with H2O2, similar to the kinetics of nuclear import of PKCδ seen in Fig. 1A. Regulated association of importin-α with PKCδ also occurs in response to etoposide and was maximal at ∼15 min post-treatment (Fig. 1E). Interaction of importin-α with PKCδ occurred prior to etoposide induced nuclear import of PKCδ, which we have previously reported to be detectable at ∼30 min following treatment with etoposide (24). As the association kinetics of PKCδ and importin-α in response to both agents closely parallels the nuclear import kinetics of PKCδ, this suggests that importin-α binding is rate-limiting for nuclear import.

Tyrosine Phosphorylation of PKCδ Facilitates Binding to Importin-α

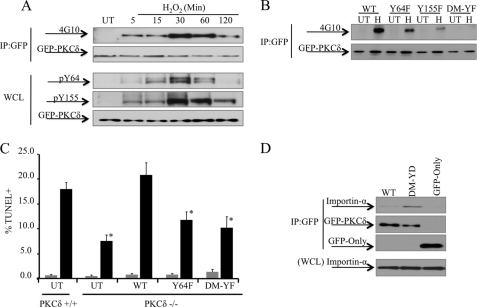

The observation that H2O2 and etoposide induce binding of PKCδ to importin-α suggests that regulated exposure of the NLS controls nuclear import. Our laboratory and others have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ in response to various stimuli regulates its subcellular localization as well as other aspects of its function (9, 27, 33–40). To explore a potential role for tyrosine phosphorylation in regulating binding of importin-α to PKCδ in response to H2O2, we first examined the kinetics of tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ in response to H2O2 using a pan phospho-tyrosine antibody (4G10). As shown in Fig. 2A, upper panels, total tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ is detected as early as 5 min post-treatment, following similar kinetics as that of importin-α binding to PKCδ (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 2.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ facilitates binding to importin-α. A, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ and were either left untreated (UT) or treated with 5 mm H2O2. Upper panels, GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from WCL using an anti-GFP antibody and assayed by Western blot for total PKCδ tyrosine phosphorylation (4G10) or for the amount of GFP-tagged protein immunoprecipitated (IP). Lower panels, WCL were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the immunoblots were probed with anti-GFP, anti-phospho-Tyr-64 or anti-phospho-Tyr-155 antibodies. B, ParC5 cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-Y64F-PKCδ (Y64F), pGFP-Y155F-PKCδ (Y155F), or pGFP-Y64/155F-PKCδ (DM-YF) and were either left untreated or treated with 1 mm H2O2 (H) for 10 min. GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from WCL using an anti-GFP antibody and assayed by Western blot for total PKCδ tyrosine phosphorylation (4G10) or for the amount of GFP-tagged protein immunoprecipitated. C, primary parotid salivary cells were isolated from PKCδ+/+ or PKCδ−/− mice. Cells were either left untransduced (UT) or transduced with Adeno-GFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), Adeno-GFP-Y64F-PKCδ (Y64F), or Adeno-GFP-Y64/155F-PKCδ (DM-YF) as indicated. Cells were either left untreated (gray bars) or were treated with 1 mm H2O2 (black bars) for 22 h, and apoptosis was assayed by TUNEL. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (Student's t test; p < 0.05) from H2O2 treated PKCδ+/+ cells. D, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-Y64D/Y155D-PKCδ (DM-YD), or pGFP. Upper panels, the GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from WCL using an anti-GFP antibody and assessed by Western blot for endogenous importin-α interaction and the amount of GFP-tagged proteins immunoprecipitated. Lower panel, WCL was assayed by Western blot to show the amount of importin-α present in the lysate. For all panels, each experiment was repeated three or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

We have previously shown that phosphorylation at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 in the regulatory domain of PKCδ is required for its nuclear import, and in turn apoptosis, in response to etoposide treatment (27). In Fig. 2A, lower panels, we show that the kinetics of phosphorylation of PKCδ at these residues parallels total tyrosine phosphorylation as detected with the pan-phosphotyrosine antibody, 4G10 (Fig. 2A, upper panels). To confirm that Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 are the major sites for tyrosine phosphorylation in response to H2O2, we transfected ParC5 cells with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), or mutants of PKCδ in which the tyrosine residues at amino acid 64 and 155 were mutated to phenylalanine: Y64F, Y155F, and Y64F/Y155F. As predicted, H2O2 treatment for 10 min resulted in an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of the wild type PKCδ (Fig. 2B). However, the PKCδ Y64F and Y155F mutants exhibited a dramatic reduction in tyrosine phosphorylation that was nearly undetectable in the Y64F, Y155F, and Y64F/Y155F mutants (Fig. 2B), confirming that these residues are the major phosphorylation tyrosine sites in response to H2O2. In addition, we show that these residues are required for H2O2-induced apoptosis, as PKCδ mutated at Y64F, and the Y64F/Y155F mutants failed to reconstitute H2O2 induced apoptosis in primary salivary cells isolated from δKO mice (Fig. 2C).

Our previous finding that a Y64D/Y155D phosphomimetic mutant of PKCδ accumulates in the nucleus in the absence of an apoptotic signal, suggests that tyrosine phosphorylation is sufficient to relieve the constraint on importin-α binding to the PKCδ NLS (27). To determine whether phosphorylation at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 is sufficient for importin-α binding, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT) or pGFP-Y64D/Y155D-PKCδ, and binding of PKCδ to importin-α was assessed by co-immunoprecipitation. As predicted, the GFP-Y64D/Y155D-PKCδ mutant had an increased ability to bind importin-α as compared with wild type PKCδ (Fig. 2D), suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation in the regulatory domain of PKCδ is sufficient for importin-α binding.

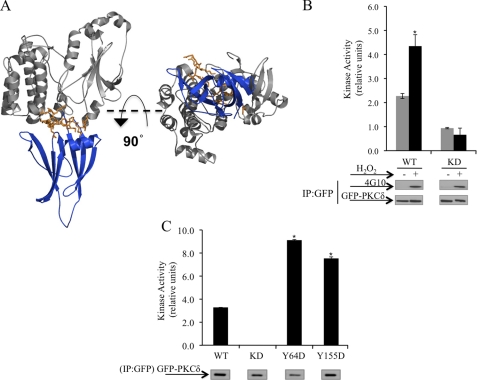

To explore the mechanism by which tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the interaction of PKCδ with importin-α, we examined a model of PKCδ in the inactive or “closed” conformation (Fig. 3A). This model is based on previous structural studies of inactive PKCδ (41). In reconstructing this model, we used the crystal structure of the C2-domain of PKCδ (41) and the catalytic domain of PKCβII (42), which shares substantial structural homology with PKCδ. In the closed conformation, the C2-domain is folded back upon the catalytic domain and is predicted to make extensive contacts with the region that contains the NLS. This model predicts that contacts between the NLS and the C2-domain limit access of importin-α to the NLS. Therefore, to allow for importin-α binding to the NLS, PKCδ must first undergo a conformational change to expose the NLS. We predict that the addition of a negative charge imparted by phosphorylation at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 facilitates a conformational change in the kinase such that the contacts between the C2 and the catalytic domains are disrupted, leading to exposure of the NLS. PKC activity in vitro in the absence of exogenous lipid is indicative of a conformation of the kinase in which the regulatory domain constraints on the catalytic domain are relieved, resulting in an active and “open” conformation of the kinase (37, 43–46). To determine whether H2O2 induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ results in an active conformation of PKCδ, we assayed the lipid-independent activity of PKCδ in cells treated with H2O2. As seen in Fig. 3B, PKCδ immunoprecipitated from H2O2 treated cells exhibited a significant increase in lipid-independent activity compared with PKCδ immunoprecipitated from untreated cells. In addition, we confirm that GFP-WT-PKCδ indeed underwent tyrosine phosphorylation in response to H2O2 treatment as detected with the pan-phosphotyrosine antibody, 4G10 (Fig. 3B, Western blots).

FIGURE 3.

H2O2 induces a conformational change in PKCδ. A, right, model of PKCδ structure in the inactive conformation using the PKCδ C2-domain structure (41) and PKCβII catalytic domain structure (42). The region in PKCβII corresponding to the NLS region in PKCδ (orange) of the kinase domain (gray) is almost completely covered by the C2-domain (blue). Left, 90° rotation of the model around its x axis. B, COS-7 cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT) or the kinase-dead pGFP-KD-PKCδ (KD) and were left untreated (gray bars) or were treated with 5 mm H2O2 (black bars). C, ParC5 cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-Y64D-PKCδ (Y64D), pGFP-155D-PKCδ (155D), or pGFP-KD-PKCδ. B and C, GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates using anti-GFP antibody, and kinase activity was assayed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The Western blots show the amount of GFP-tagged proteins immunoprecipitated (IP). B, PKCδ total tyrosine phosphorylation (4G10) is shown. The kinase activity was normalized to the amount of immunoprecipitated GFP-tagged protein and is expressed as relative units. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from WT (Student's t test; p < 0.05). For all panels, each experiment was repeated three or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

To determine whether phosphorylation at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 is sufficient to induce lipid independent activity of PKCδ, we assayed the lipid-independent activity of phosphomimetic mutants of PKCδ at these sites. As seen in Fig. 3C, in the absence of added lipids, the activity of the Y64D and Y155D mutants is increased 2.5- to 3-fold compared with WT. No additional increase in the lipid independent activity was observed with the Y64D/Y155D mutant (data not shown). Taken together, these studies suggest that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ in the regulatory domain, downstream of H2O2 treatment, alters the conformation of the kinase and results in exposure of the NLS and subsequent binding to importin-α.

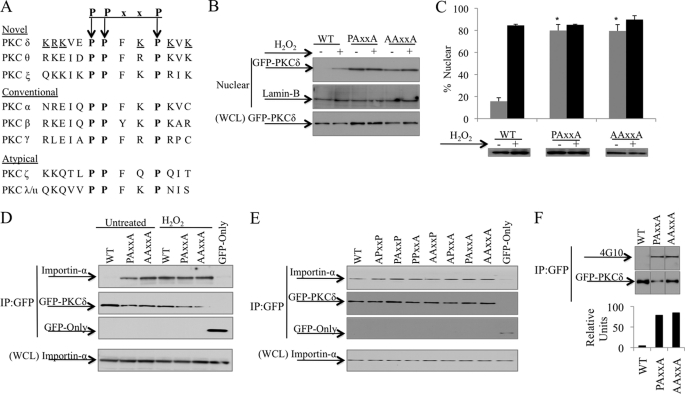

PPxxP Motif Facilitates Retention of PKCδ in the Cytoplasm

Our studies indicate that intramolecular contacts between the C2 and the catalytic domains regulate access of importin-α to the PKCδ NLS and, in turn, nuclear import of PKCδ. Curiously, the region of the catalytic domain where the C2-domain makes extensive contacts corresponds to a highly conserved PPxxP motif at the C-terminal tail of PKCδ (Fig. 4A). In PKCδ, this motif overlaps the bipartite NLS, suggesting that it may play a role in regulating access of importin-α to the NLS. Based on its unique location in the NLS and its proposed role in intramolecular interactions, we hypothesize that the PPxxP motif may contribute to the conformational constraints that limit importin-α binding to PKCδ in resting cells (47). To test this directly, we mutated the conserved proline residues to alanine and assessed accumulation of the GFP-tagged proteins in nuclear fractions of transfected cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, very little GFP-WT-PKCδ is found in the nucleus of unstimulated cells; however, upon stimulation with H2O2, GFP-WT-PKCδ accumulation in the nucleus increases substantially. In contrast, both GFP-PAxxA-PKCδ and GFP-AAxxA-PKCδ accumulated in the nucleus in resting cells, and H2O2 treatment resulted in little or no increase in the nuclear targeting of these mutants compared with the wild type protein, suggesting that the integrity of the PPxxP motif is required for the cytoplasmic retention of PKCδ. Nuclear targeting of the PPxxP mutant proteins was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy in ParC5 cells transfected with GFP-tagged proteins (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

The PPxxP motif facilitates retention of PKCδ in the cytoplasm. A, a conserved PPxxP motif (boldface) overlaps the bipartite NLS (underlined) of PKCδ. B, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-PAxxA-PKCδ (PAxxA), or pGFP-AAxxA-PKCδ (AAxxA) and were left untreated or treated with 5 mm H2O2 for 30 min. Nuclear fractions and WCL were separated by SDS-PAGE, and Western blots were probed with an anti-GFP antibody. Lamin-B was used as a loading control for nuclear fractions. C, ParC5 cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-PAxxA-PKCδ (PAxxA), or pGFP-AAxxA-PKCδ (AAxxA) and either left untreated (gray bars) or treated with 5 mm H2O2 (black bars) for 1 h. Nuclear localization of GFP-tagged proteins was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The Western blot shows protein expression of the different constructs. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from untreated WT (Student's t test; p < 0.002). D, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP, pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-PAxxA-PKCδ (PAxxA), or pGFP-AAxxA-PKCδ (AAxxA) and were either left untreated or treated with 5 mm H2O2 for 30 min. E, 293T cells were transfected with the indicated pGFP2-PPxxP constructs or pGFP. D and E, upper panels, the GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from WCL using an anti-GFP antibody and assayed by Western blot for endogenous importin-α interaction and the amount of GFP-tagged proteins immunoprecipitated (IP). Lower panels, WCL was assayed by Western blot to show the amount of importin-α present in the lysate. F, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-PAxxA-PKCδ (PAxxA), or pGFP-AAxxA-PKCδ (AAxxA). The GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from WCL using an anti-GFP antibody and assayed by Western blot for total PKCδ tyrosine phosphorylation (4G10) and the amount of GFP-tagged immunoprecipitated. The graph represents densitometric analysis of the above Western blots quantifying the amount of PKCδ total tyrosine phosphorylation relative to protein levels. For all panels, each experiment was repeated three or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

To determine whether nuclear accumulation of the PPxxP mutants results from increased binding to importin-α, GFP-tagged PPxxP mutants of PKCδ were immunoprecipitated from transfected cells and probed for importin-α binding. Fig. 4D shows that the increased nuclear accumulation of the PKCδ PPxxP mutants correlates with increased importin-α binding in resting cells compared with the wild type protein, and H2O2 treatment resulted in little or no increase in importin-α binding to these mutants. To explore whether constraints imposed by the PPxxP motif are dependent on the conformation of the full-length kinase, we analyzed importin-α binding to a 13-amino acid peptide of the PKCδ NLS that is either wild type or mutated at one or more prolines in the PPxxP tagged with two GFP proteins in tandem (GFP2). As shown in Fig. 4E, mutation of single or multiple proline residues in the context of the NLS peptide results in little or no change in importin-α binding, suggesting that the constraints imposed by this region are dependent on its participation in intramolecular contacts with other regions of the kinase. Notably, mutation of the PPxxP motif also results in a 20-fold increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ in the absence of apoptotic stimuli (Fig. 4F), presumably due to exposure of tyrosine residues for phosphorylation. We conclude that the PPxxP motif per se does not regulate importin-α binding, but rather contacts between this motif and the C2-domain may be important for stabilizing a conformational state of PKCδ in which binding of importin-α to the NLS is inhibited.

Hsp90 Binding Is Required for PKCδ Binding to Importin-α

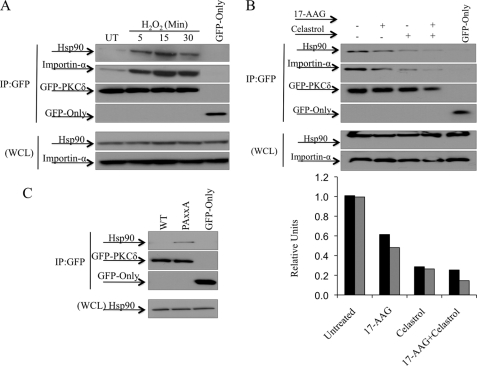

Recent work by Gould et al. (47) has implicated regions C- and N-terminal of the PPxxP motif in mediating binding of Hsp90 to PKCβII. To explore a potential role for Hsp90 in regulating nuclear import of PKCδ, we assessed whether binding of Hsp90 to PKCδ is regulated in response to H2O2 treatment. H2O2 treatment induced binding of Hsp90 to PKCδ with the same kinetics as importin-α binding, suggesting that Hsp90 may facilitate binding of importin-α to PKCδ (Fig. 5A). To address this directly, we treated cells with Celasterol or 17-AAG, both of which inhibit Hsp90 binding to its client proteins (48–50). Both Celastrol and 17-AAG disrupted Hsp90 binding to PKCδ as well as the interaction of importin-α with PKCδ (Fig. 5B). As determined by densitometry, treatment with 17-AAG, Celastrol, or both agents resulted in loss of a similar amount of both Hsp90 and importin-α binding to PKCδ (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the proline-to-alanine mutation of the PPxxP, which enhances the association with importin-α and nuclear import of PKCδ (Fig. 4D), also results in increased interaction of PKCδ with Hsp90 (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these studies suggest that Hsp90 interaction with PKCδ may be important for stabilizing a conformation that facilitates exposure of the NLS, thus allowing its interaction with importin-α.

FIGURE 5.

Hsp90 binding is required for PKCδ binding to importin-α. A, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ or pGFP and were either left untreated (UT) or treated with 5 mm H2O2 as indicated. B, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ or pGFP and were either left untreated or challenged with either 1 μm 17-AAG for 3 h, 10 μm Celastrol for 30 min, or both. C, 293T cells were transfected with pGFP-WT-PKCδ (WT), pGFP-PAxxA-PKCδ (PAxxA), or pGFP. A–C, upper panels, the GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from WCL using an anti-GFP antibody, and the immunocomplexes were assayed by Western blot for endogenous importin-α and Hsp90 interaction, and the amount of GFP-tagged protein immunoprecipitated (IP). Lower panels, WCL was assayed by Western blot to show the amount of importin-α and Hsp90 present in the lysates. B, the graph represents densitometric analysis of the above Western blots quantifying the amount of Hsp90 (black bars) and the amount of importin-α (gray bars) bound to PKCδ relative to the amount of GFP-tagged protein immunoprecipitated. For all panels, each experiment was repeated three or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

DISCUSSION

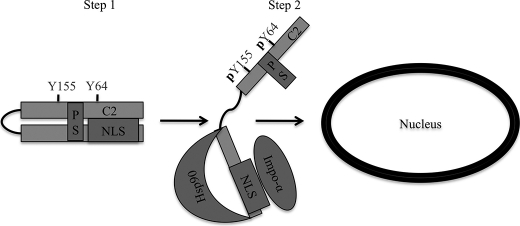

We have previously demonstrated that nuclear localization of PKCδ in response to apoptotic stimuli is both required and sufficient for its proapoptotic function (23, 24). Here, we explored the mechanism that retains PKCδ in the cytoplasm under resting conditions and regulates its nuclear import in response to apoptotic stimuli. We show that in resting cells, PKCδ is kept in a conformation that prevents binding of its NLS to importin-α. However, upon stimulation with H2O2 or etoposide, PKCδ binds to importin-α with kinetics similar to that of the nuclear import of PKCδ. Our studies indicate that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKC facilitates binding of importin-α to PKCδ, and that binding of importin-α to the NLS is stabilized by Hsp90 (see model in Fig. 6). The tight regulation of nuclear import assures cytoplasmic retention of PKCδ under basal conditions and nuclear import and induction of apoptosis only when appropriate.

FIGURE 6.

A model for nuclear localization of PKCδ. Step 1, PKCδ is retained in the cytoplasm of resting cells through a closed conformation that is refractory to importin-α binding to the NLS in the absence of apoptotic stimuli. Step 2, in response to apoptotic stimuli, such as etoposide or H2O2, PKCδ is phosphorylated at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155. Tyrosine phosphorylation results in an open conformation of PKCδ allowing exposure of the NLS as well as binding sites for Hsp90, where importin-α and Hsp90 can bind, respectively. Once bound to importin-α, PKCδ then translocates into the nucleus. C2, C2-domain; PS, pseudosubstrate domain.

Maintaining a balance between nuclear and cytoplasmic levels of a given protein can be crucial for determining cell fate; therefore nucleocytoplasmic shuttling is a highly orchestrated process and is often coupled with other levels of regulation such as protein phosphorylation. In most cases, phosphorylation enhances nuclear import of cargo proteins, although abrogation of nuclear import has been reported (51). Currently, only a few studies have described the molecular mechanism by which phosphorylation either enhances or abrogates nuclear import. STAT1 (signal transducers and activators of transcription) phosphorylation induces its homo-dimerization, forming a dimer-specific NLS that is recognized by importin-α (52). Phosphorylation of 14-3-3 leads to its dissociation from c-Abl, exposing the NLS of the latter and inducing its nuclear import (53). Here, we report that in the context of PKCδ, phosphorylation regulates exposure of a hidden NLS through remodeling of intramolecular interactions.

We show that in addition to etoposide, phosphorylation at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 is also required for H2O2-induced apoptosis (27). Our studies suggest that Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 are the primary sites for tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ in H2O2-treated ParC5 cells. In contrast, Konishi et al. (37, 38), using COS-7 cells, have shown that PKCδ is phosphorylated on additional residues in response to H2O2, most of which are in the catalytic domain. To show that tyrosine phosphorylation at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 is functionally significant, we have mimicked the negative charge imparted on these residues by phosphorylation and have shown that the resulting mutant (Y64D/Y155D) has enhanced binding to importin-α. This suggests that phosphorylation of PKCδ at Tyr-64 and Tyr-155 may regulate access of importin-α to PKCδ. Consistent with a conformational change induced by tyrosine phosphorylation, we show that H2O2 induces lipid-independent activity of PKCδ and that the Y64D and Y155D phosphomimetic mutants of PKCδ have a significantly higher lipid independent activity compared with the wild type protein. Furthermore, a model of the closed conformation of PKCδ, suggests that the C2-domain makes extensive contacts with the region of the catalytic domain containing the NLS, sterically hindering access of importin-α to the NLS. Likewise, in the crystal structure of full-length PKCβII, the C2-domain is also positioned so that it partially occludes access to the same region of the protein that contains the NLS in PKCδ, suggesting that these structural contacts are likely conserved, at least in the novel and conventional family of PKCs (supplemental Fig. 1).

Next, we explored the role of the highly conserved PPxxP motif that overlaps the NLS of PKCδ. Gould et al. (47) has recently shown that this motif is required for proper priming site phosphorylation of PKCβII, which we confirm is also true for PKCδ (data not shown). We showed that proline-to-alanine mutagenesis of the PPxxP motif results in enhanced binding to importin-α and nuclear import of PKCδ. This suggests that the integrity of this motif is required for the cytoplasmic retention of PKCδ by preventing access of the NLS to importin-α. However, a 13-amino acid peptide of the region containing the PPxxP revealed no difference between the proline-to-alanine mutants and wild type PPxxP motif in terms of binding to importin-α. This suggests that the role of the PPxxP motif in limiting access of importin-α to the NLS is unique to the full-length protein. This is consistent with our earlier work showing that the catalytic fragment of PKCδ translocates into the nucleus without apoptotic stimuli (23), further suggesting that the molecular contacts that confer cytoplasmic retention of PKCδ require the C2-domain.

H2O2 induced association of Hsp90 with PKCδ with kinetics similar to that of importin-α. Furthermore, we show that Hsp90 binding is required for the association of PKCδ with importin-α. In addition, we show that proline-to-alanine mutagenesis of the PPxxP motif enhanced the association of Hsp90 with PKCδ. This suggests that both H2O2 treatment and PPxxP mutagenesis facilitate the availability of Hsp90-interacting regions on PKCδ. These observations are in agreement with the well established role of Hsp90 in binding to and stabilizing hydrophobic regions of proteins that become exposed in the open active conformation (54, 55). In the study by Gould et al. (47) the sites for Hsp90 binding were mapped to regions C and N terminus to the PPxxP motif, but not the PPxxP motif itself. In PKCδ, the PPxxP overlaps the NLS, the site for importin-α binding. This suggests that Hsp90 binding is likely involved in stabilizing a conformation that favors importin-α binding to the NLS of PKCδ, rather than directly mediating this interaction. This is consistent with the role of Hsp90 in unmasking the NLS of the dioxin receptor, allowing importin-α binding and nuclear import of the dioxin receptor upon ligand binding (56).

In summary, our studies elucidate a novel mechanism for regulated nuclear import of PKCδ as shown in the model in Fig. 6. We describe the steps and structural components involved in retaining PKCδ in the cytosol of resting cells and in regulating its nuclear import in response to apoptotic agents. These findings provide insight for the design of rational therapeutic strategies aimed at manipulating the proapoptotic function of PKCδ by control of its subcellular localization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alexandra C. Newton and Dr. Peter J. Parker for reagents and insightful discussions during the course of these studies.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- NLS

- nuclear localization sequence

- WCL

- whole cell lysate

- 17-AAG

- 17-allylamino-demethoxy geldanamycin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jackson D., Zheng Y., Lyo D., Shen Y., Nakayama K., Nakayama K. I., Humphries M. J., Reyland M. E., Foster D. A. (2005) Oncogene 24, 3067–3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miyamoto A., Nakayama K., Imaki H., Hirose S., Jiang Y., Abe M., Tsukiyama T., Nagahama H., Ohno S., Hatakeyama S., Nakayama K. I. (2002) Nature 416, 865–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu J., Someren E., Mentink A., Licht R., Dechering K., van Blitterswijk C., de Boer J. (2010) J. Tissue Eng. Regen Med. 4, 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mecklenbräuker I., Saijo K., Zheng N. Y., Leitges M., Tarakhovsky A. (2002) Nature 416, 860–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson D. N., Foster D. A. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 627–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li W., Jiang Y. X., Zhang J., Soon L., Flechner L., Kapoor V., Pierce J. H., Wang L. H. (1998) Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 5888–5898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leitges M., Mayr M., Braun U., Mayr U., Li C., Pfister G., Ghaffari-Tabrizi N., Baier G., Hu Y., Xu Q. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1505–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Voss O. H., Kim S., Wewers M. D., Doseff A. I. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17371–17379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Humphries M. J., Limesand K. H., Schneider J. C., Nakayama K. I., Anderson S. M., Reyland M. E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9728–9737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matassa A. A., Carpenter L., Biden T. J., Humphries M. J., Reyland M. E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29719–29728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reyland M. E., Anderson S. M., Matassa A. A., Barzen K. A., Quissell D. O. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19115–19123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reyland M. E., Barzen K. A., Anderson S. M., Quissell D. O., Matassa A. A. (2000) Cell Death Differ. 7, 1200–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Majumder P. K., Mishra N. C., Sun X., Bharti A., Kharbanda S., Saxena S., Kufe D. (2001) Cell Growth Differ. 12, 465–470 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matassa A. A., Kalkofen R. L., Carpenter L., Biden T. J., Reyland M. E. (2003) Cell Death Differ. 10, 269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yoshida K. (2007) Cell Signal 19, 892–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yuan Z. M., Utsugisawa T., Ishiko T., Nakada S., Huang Y., Kharbanda S., Weichselbaum R., Kufe D. (1998) Oncogene 16, 1643–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Symonds J. M., Ohm A. M., Carter C. J., Heasley L. E., Boyle T. A., Franklin W. A., Reyland M. E. (2011) Cancer Res. 71, 2087–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosse C., Linch M., Kermorgant S., Cameron A. J., Boeckeler K., Parker P. J. (2010) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gallegos L. L., Newton A. C. (2008) IUBMB Life 60, 782–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Violin J. D., Newton A. C. (2003) IUBMB Life 55, 653–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reno E. M., Haughian J. M., Dimitrova I. K., Jackson T. A., Shroyer K. R., Bradford A. P. (2008) Hum. Pathol. 39, 21–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mecklenbräuker I., Kalled S. L., Leitges M., Mackay F., Tarakhovsky A. (2004) Nature 431, 456–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. DeVries T. A., Neville M. C., Reyland M. E. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 6050–6060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DeVries-Seimon T. A., Ohm A. M., Humphries M. J., Reyland M. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22307–22314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feldherr C., Akin D., Littlewood T., Stewart M. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 2997–3005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson S. M., Reyland M. E., Hunter S., Deisher L. M., Barzen K. A., Quissell D. O. (1999) Cell Death Differ. 6, 454–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Humphries M. J., Ohm A. M., Schaack J., Adwan T. S., Reyland M. E. (2008) Oncogene 27, 3045–3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chook Y. M., Blobel G. (2001) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 703–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Damelin M., Silver P. A., Corbett A. H. (2002) Methods Enzymol. 351, 587–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kakuk A., Friedländer E., Vereb G., Jr., Lisboa D., Bagossi P., Tóth G., Gergely P., Vereb G. (2008) Exp. Cell Res. 314, 2376–2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lange A., Mills R. E., Lange C. J., Stewart M., Devine S. E., Corbett A. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5101–5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leung S. W., Harreman M. T., Hodel M. R., Hodel A. E., Corbett A. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41947–41953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kajimoto T., Shirai Y., Sakai N., Yamamoto T., Matsuzaki H., Kikkawa U., Saito N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12668–12676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Okhrimenko H., Lu W., Xiang C., Ju D., Blumberg P. M., Gomel R., Kazimirsky G., Brodie C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23643–23652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tapia J. A., García-Marin L. J., Jensen R. T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35220–35230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kronfeld I., Kazimirsky G., Lorenzo P. S., Garfield S. H., Blumberg P. M., Brodie C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35491–35498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Konishi H., Tanaka M., Takemura Y., Matsuzaki H., Ono Y., Kikkawa U., Nishizuka Y. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11233–11237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Konishi H., Yamauchi E., Taniguchi H., Yamamoto T., Matsuzaki H., Takemura Y., Ohmae K., Kikkawa U., Nishizuka Y. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6587–6592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Acs P., Beheshti M., Szállási Z., Li L., Yuspa S. H., Blumberg P. M. (2000) Carcinogenesis 21, 887–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li W., Chen X. H., Kelley C. A., Alimandi M., Zhang J., Chen Q., Bottaro D. P., Pierce J. H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 26404–26409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Solodukhin A. S., Kretsinger R. H., Sando J. J. (2007) Cell Signal. 19, 2035–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leonard T. A., Róycki B., Saidi L. F., Hummer G., Hurley J. H. (2011) Cell 144, 55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kheifets V., Mochly-Rosen D. (2007) Pharmacol. Res. 55, 467–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Newton A. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28495–28498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Newton A. C. (2003) Biochem. J. 370, 361–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Newton A. C. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, S266–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gould C. M., Kannan N., Taylor S. S., Newton A. C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4921–4935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Whitesell L., Lindquist S. L. (2005) Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kamal A., Boehm M. F., Burrows F. J. (2004) Trends Mol. Med. 10, 283–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Taldone T., Sun W., Chiosis G. (2009) Bioorg Med. Chem. 17, 2225–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nardozzi J. D., Lott K., Cingolani G. (2010) Cell Commun Signal 8, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McBride K. M., Banninger G., McDonald C., Reich N. C. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 1754–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yoshida K., Miki Y. (2005) Cell Cycle 4, 777–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Giannini A., Bijlmakers M. J. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 5667–5676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. An W. G., Schulte T. W., Neckers L. M. (2000) Cell Growth Differ. 11, 355–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kazlauskas A., Sundström S., Poellinger L., Pongratz I. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 2594–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.