Background: PDGF-induced migration in VSMCs requires Slingshot (SSH1L) phosphatase activity.

Results: We found SSH1L_Ser834 auto-dephosphorylation disrupts a SSH1L/14-3-3 complex and increases PDGF-induced SSH1L activity in wild type but not in Nox1-/y cells.

Conclusion: PDGF activates SSH1L in VSMC by a mechanism that involves Nox1-mediated oxidation of 14-3-3 and Ser834-SSH1L auto-dephosphorylation.

Significance: We establish the PDGF-induced SSH1L activation mechanism, required for VSMC migration.

Keywords: Cytoskeleton, NADPH Oxidase, Protein Phosphatase, Redox Signaling, Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells, Nox1

Abstract

Migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) contributes to vascular pathology. PDGF induces VSMC migration by a Nox1-based NADPH oxidase mediated mechanism. We have previously shown that PDGF-induced migration in VSMCs requires Slingshot-1L (SSH1L) phosphatase activity. In the present work, the mechanism of SSH1L activation by PDGF is further investigated. We identified a 14-3-3 consensus binding motif encompassing Ser-834 in SSH1L that is constitutively phosphorylated. PDGF induces SSH1L auto-dephosphorylation at Ser-834 in wild type (wt), but not in Nox1−/y cells. A SSH1L-S834A phospho-deficient mutant has significantly lower binding capacity for 14-3-3 when compared with the phospho-mimetic SSH1L-S834D mutant, and acts as a constitutively active phosphatase, lacking of PDGF-mediated regulation. Given that Nox1 produces reactive oxygen species, we evaluated their participation in this SSH1L activation mechanism. We found that H2O2 activates SSH1L and this is accompanied by SSH1L/14-3-3 complex disruption and 14-3-3 oxidation in wt, but not in Nox1−/y cells. Together, these data demonstrate that PDGF activates SSH1L in VSMC by a mechanism that involves Nox1-mediated oxidation of 14-3-3 and Ser-834 SSH1L auto-dephosphorylation.

Introduction

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)2 comprise the majority of cells in blood vessel walls. In physiological conditions, these cells are in a fully differentiated, contractile phenotype. However, under pathological circumstances, VSMCs switch to a proliferative and migratory phenotype, contributing to vascular diseases including atherosclerosis and postangioplasty restenosis (1).

Efficient remodeling and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton is essential for migration to occur. Actin dynamics are regulated in part by the cofilin/ADF family of proteins. We have demonstrated that Slingshot-1L (SSH1L) is the phosphatase responsible for PDGF-induced cofilin dephosphorylation and activation in VSMCs, and that its activation is required for PDGF-induced migration (2). These findings point to a central role for SSH1L in regulating VSMC migration, and as a result, this protein represents an excellent potential therapeutic target for dysregulated migration. Unlike kinases, whose activity is mainly regulated by direct, post-translational modifications, the activity and specificity of many phosphatases is governed largely by their association with regulatory proteins, such as 14-3-3 (3).

The 14-3-3 proteins function as phosphoserine/phosphothreonine-binding modules. Although the specific functions of 14-3-3 proteins are not fully understood (4), this family of proteins regulates important cellular processes, including cell cycle control, apoptosis, and growth (5). Of the seven isoforms comprising this family, 14-3-3-γ and -β have been shown to be expressed in VSMC (6–8). Canonically, 14-3-3 proteins bind to a specific phosphoserine/phosphothreonine consensus sequence in their partners (9). Different 14-3-3 isoforms have been shown to interact with SSH1L and form an inhibitory complex by sequestering it in the cytosolic fraction (10–13).

The mechanisms of SSH1L activation and in particular the pathways by which PDGF controls VSMC migration are still far from clear. However, it is well established that reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is required for VSMC migration induced by PDGF (14) and that PDGF induces ROS production in VSMC through a Nox1-based NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanism (15). We have recently reported that VSMCs derived from Nox1−/y (knockout) animals have impaired migration and less active cofilin when compared with wild type (15), suggesting that Nox1−/y cells fail to properly activate SSH1L phosphatase. Based on these observations and the report that SSH1L may complex with 14-3-3 proteins (12, 16, 17), we hypothesized that SSH1L contains a 14-3-3 binding motif that is dephosphorylated by PDGF in a Nox1-dependent manner, thus activating SSH1L. We found that dephosphorylation of SSH1L on serine 834 governs its activity in this cell type, and identified a unique auto-dephosphorylation mechanism that requires a Nox-1-based oxidase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

VSMCs were isolated from wild type (wt) and Nox1−/y mouse aortas by enzymatic dissociation (34). Human aortic smooth muscle cells (HASMC) were purchased from Invitrogen, HEK293 cells were purchased from Stratagene (AD293 cat. # 240085). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics, and used between passages 6 and 12. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cultures at 70–80% confluence were made quiescent by incubation in serum-free media for 48 h prior to treatment with platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB, human recombinant, BD Biosciences).

Plasmids

The plasmid coding for cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-tagged human SSH1L (SSH1L-CFP) was constructed by subcloning SSH1L cDNA into pECFP-C1 (Clontech) and was a kind gift from Dr. Kenzaku Mizuno, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan. Hexahistidine-tagged 14-3-3γ construct was a kind gift from Dr. Haian Fu, Emory University.

Western Blotting and Antibodies

After treatment, cells were lysed in 1% Triton-containing lysis buffer and analyzed by Western blotting. Samples (20 μg of total protein or immunoprecipitates from 1 mg of total cell proteins) were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels (Invitrogen) and separated by size using electrophoresis. Proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes for 1 h. The membranes were then blotted for 1 h with 5% milk. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against phospho-Ser3-cofilin and phospho-14-3-3 binding motif recognizing the sequence R-X-X-S*-X-P (Cell Signaling 3311 and 9606, respectively), cofilin (GeneTex (GTX102156) and pan-14-3-3 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-1657). Anti-human SSH1L and anti-GFP (with CFP cross-reactivity) were from Abcam (ab46202 and ab6662, respectively). Rabbit polyclonal antibody against mouse SSH1L was custom made by GenScript. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, proteins were detected by ECL chemiluminescence HRP substrate (GE Healthcare RPN 2132) for 5 min. The films were analyzed by densitometry with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunoprecipitation and Pull-down of His-tagged Proteins

VSMCs were lysed with HEPES lysis buffer containing 1% Triton. Cell lysates were normalized for the total amount of protein and 1 mg of lysate was immunoprecipitated using anti human SSH1L or CFP from Abcam (ab76943 and ab291, respectively) or anti mouse SSH1L (custom made, GeneScript). The complexes were isolated with Dynabeads M-280 sheep anti-rabbit IgG.

To test for SSH1L/14-3-3 interactions, a Tris pH 7.5 buffer with 0.5% Nonidet P-40 was used. Co-immunoprecipitations were performed using specific antibodies against mouse SSH1L (GeneScript) or pan- or gamma-14-3-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Millipore, respectively) as indicated. His-Tag Isolation Dynabeads from Invitrogen were used for His pull-down according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Phosphatase Activity Assay

To evaluate endogenous SSH1L phosphatase activity, cells from wt and Nox1−/y mouse or human Aortic smooth muscle were stimulated with PDGF (10 ng/ml) or vehicle for 20 min. SSH1L was immunoprecipitated from VSMCs with a specific antibody (GenScript custom made for mouse cells and Abcam ab76943 for human cells) using Tris pH 7.5 buffer. Phosphatase activity was measured in the immunoprecipitates for 15 min at 37 °C using an in vitro phosphatase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and 200 μm of a custom-made phospho-cofilin peptide that mimics the N terminus of cofilin (MAS(PO4)GVA) as a substrate.

To evaluate the ability of SSH1L-S834A to dephosphorylate endogenous SSH1L, SSH1-S834A-GFP, and PP2A were recovered by immunoprecipitation (ab291 and ab32141, respectively), and untransfected cells were used to immunoprecipitate endogenous SSH1L (ab76943) as a substrate for the reaction as described above. The release of free phosphate was evaluated by its colorimetric reaction with malachite green, and the color intensity was measured in a 96-well plate using a μQuant spectrophotometer (microplate reader) at 600 nm. The amount of free phosphate was calculated using a standard curve constructed using inorganic phosphate.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Primers were created to introduce mutations in the serine phosphorylation sites of SSH1L using the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. DNA was subjected to Sanger-based automated DNA sequencing by Agencourt Bioscience.

Transfection

Cells were transfected by electroporation using the Amaxa system. VSMCs were transfected with 5 μg of either wild type or SSH1L-S834A mutant DNA using the Nucleofector set to the U25 program. HEK 293 cells were transfected with either 3 μg of SSH1L-S834A DNA and empty vector or co-transfected with 2.5 μg of 14-3-3-His tag and 1 μg of SSH1L-S834A using the Nucleofector set to the A23 program.

Labeling with 5-Iodoacetamido Fluorescein (5-IAF)

To evaluate the amount of oxidation of sulfydryl groups, we labeled them with 5-iodoacetamido fluorescein (5-IAF) using a method previously described (18). Briefly, cells were lysed using MES buffer pH 6.5 bubbled with argon for 60 min before the experiment. Then, the 5-IAF oxidation assay was performed by adding a 5-IAF solution to the cell lysate to a final concentration of 10 μm. The reaction was then incubated for 1 h in the dark at 4 °C. After the incubation period, β-mercaptoethanol to a final concentration of 20 mm was added to stop the reaction. The lysates were subjected to overnight immunoprecipitation using 5 μg of fluorescein antibody (ab6213, abcam). The amount of 14-3-3 pulled down was quantified by blotting with a 14-3-3-specific antibody (scbt1657).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± S.E. (standard error of the mean). Differences among groups were analyzed using t-test or ANOVA, with post hoc contrasts adjusted according to the Duncan or Bonferroni correction using SPSS 14.0 for Windows. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

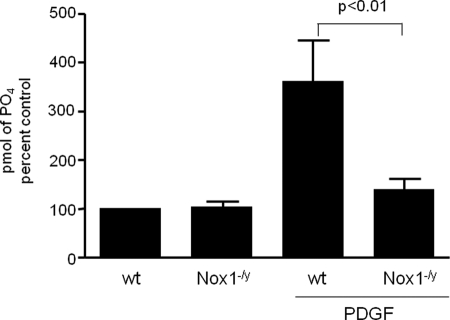

Our previous work showed that in VSMCs, SSH1L activity is required for PDGF-induced migration (2) and that cells derived from Nox1−/y animals have impaired PDGF-induced migration, a phenotype that is reversed by a constitutively active form of cofilin (S3A) (15). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that Nox1-derived H2O2 is involved in the PDGF-induced SSH1L activation mechanism. Therefore, we compared PDGF-induced SSH1L activity in VSMCs derived from wt and Nox1−/y animals. As shown in Fig. 1, in wt cells, PDGF increases SSH1L activity by about 4-fold, while it fails to induce this activity in Nox1−/y cells. This result demonstrates that Nox1 is a key component in the signaling pathway that leads to SSH1L activation after PDGF treatment in VSMCs.

FIGURE 1.

SSH1L activity is induced by PDGF in wt VSMCs, but not in cells derived from Nox1−/y animals. After stimulation of wt and Nox1−/y VSMCs with PDGF (10 ng/ml, 30 min), SSH1L phosphatase activity was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Bars represent mean ± S.E. average of four independent experiments.

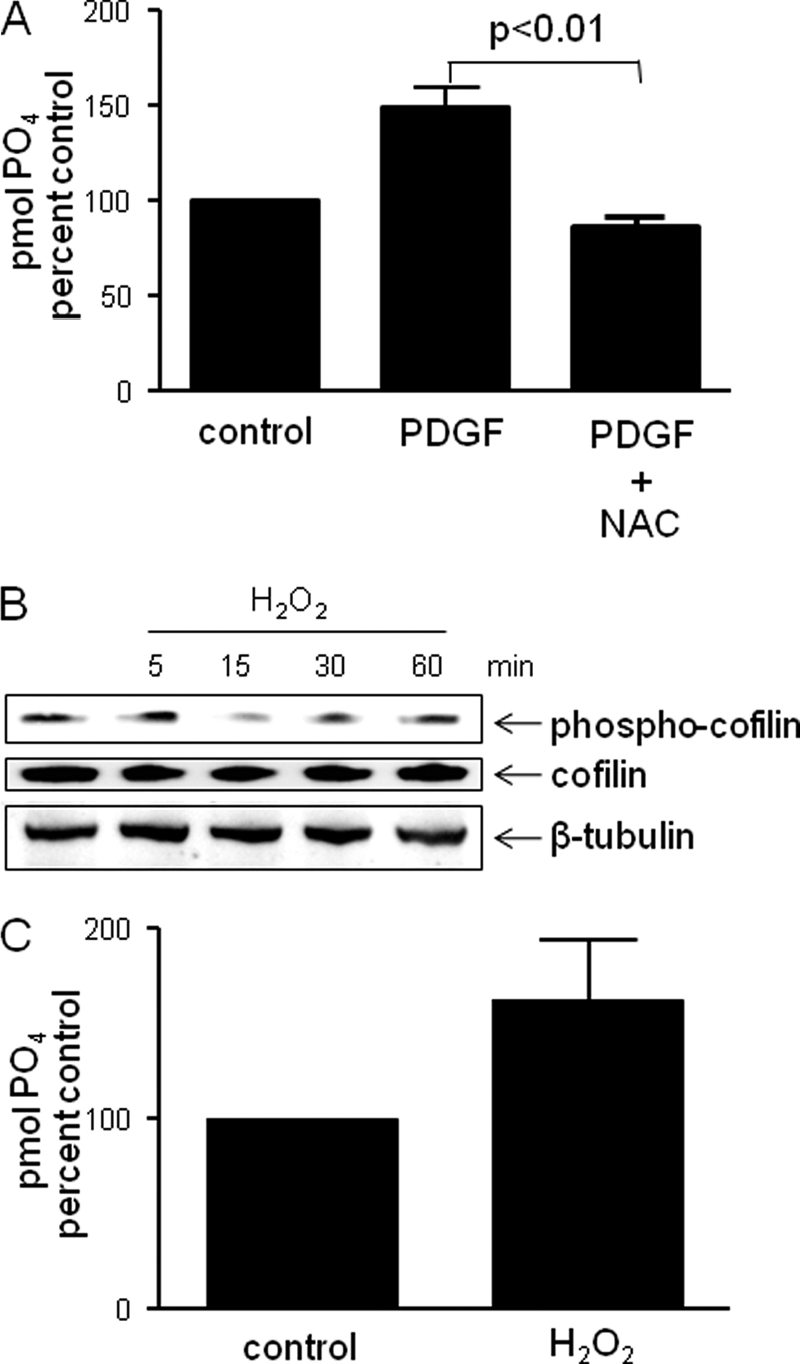

It has been established by us and others that PDGF utilizes Nox1-generated H2O2 as a signaling molecule to stimulate proliferation, proinflammatory processes and migration (14, 19, 20). For that reason, we first evaluated the ability of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to inhibit the PDGF-induced SSH1L phosphatase activity. We found that when cells are pretreated with NAC, PDGF fails to induce SSH1L activity (Fig. 2A). We therefore tested whether treatment of VSMCs with exogenous H2O2 could mimic the effect of PDGF-induced Nox1 activation on SSH1L. As shown in Fig. 2B, H2O2 (100 μm) induces dephosphorylation of the SSH1L substrate cofilin. Remarkably, SSH1L phosphatase activity is also increased after 30 min of H2O2 treatment (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

SSH1L phosphatase activation is mediated by H2O2. A, N-acetylcysteine blocks PDGF-induced SSH1L phosphatase activity. Human smooth muscle cells were serum deprived for 48 h and pretreated with 20 nm NAC for 1 h before PDGF stimulation 30 min. SSH1L phosphatase activity was measured after immunoprecipitation. Bar graph is representative of three independent experiments. B, exogenous H2O2 induces cofilin dephosphorylation. VSMCs were serum starved for 48 h, and then stimulated for the indicated times with 100 μm H2O2. Cell lysates were harvested and protein phosphorylation measured using Western blots probed with p-cofilin antibody. The blot is representative of three independent experiments. C, exogenous H2O2 induces SSH1L activation.VSMCs were treated with 100 μm H2O2 for 30 min. SSH1L phosphatase activity was measured after immunoprecipitation. Data represent mean ± S.E. of two independent experiments.

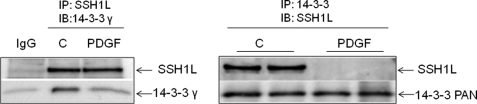

Although studied mostly with tyrosine phosphatases, the effect of oxidative modifications on protein phosphatases is universally inhibitory (21). This suggests that Nox1-derived H2O2 is unlikely to activate SSH1L by direct modification. For this reason, and since unlike kinases, the activity of protein phosphatases is mainly governed by interaction with regulatory proteins (3), we focused on the possibility that Nox1-derived H2O2 regulates the interaction of SSH1L with an inhibitory binding protein. As noted above, in other cell types, it has been reported that 14-3-3 proteins negatively regulate SSH1L activity by sequestering it in the cytoplasm, in an interaction that depends upon the phosphorylation of SSH1L (12, 13, 16). Consequently, we investigated if these two proteins interact in VSMCs. We found that SSH1L coimmunoprecipitates with 14-3-3 in unstimulated VSMCs. Importantly, we observed that this interaction is disrupted when the cells are exposed to PDGF for 15 min (Fig. 3). This agrees with a possible role of SSH1L/14-3-3 complex disruption in Nox1-dependent, PDGF-induced SSH1L activation in VSMCs.

FIGURE 3.

14-3-3 forms a complex with SSH1L, which is disrupted after PDGF treatment. VSMCs were incubated with vehicle or PDGF (10 ng/ml for 15 min). Left, co-immunoprecipitation was performed using a primary antibody against SSH1L. The membrane was then immunoblotted using anti-SSH1L and anti-14-3-3γ antibodies. Right, co-immunoprecipitation was performed using a primary antibody against pan 14-3-3. The membrane was then immunoblotted using anti-SSH1L and anti-pan14-3-3 antibodies. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

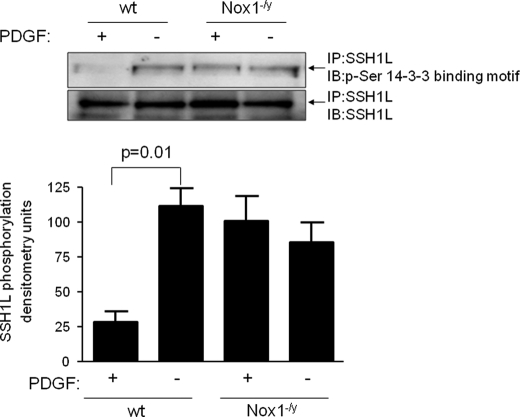

Usually, 14-3-3 recognizes and binds to serine or threonine phospho-modules within their partner proteins. Therefore, we evaluated if PDGF induces the dephosphorylation of phospho-threonine or phospho-serine residues within consensus 14-3-3 binding motifs. We did not observe any changes in threonine phosphorylation in either basal or PDGF-stimulated conditions (data acquired using the specific phosphothreonine antibody Q7 from Qiagen, not shown). On the other hand, using a specific phospho-Ser 14-3-3 binding motif antibody that recognizes the sequence R-X-X-S*-X-P, we observed that SSH1L is constitutively serine phosphorylated in a 14-3-3 binding motif, and, interestingly, that PDGF induces dephosphorylation of this site in wt but not in Nox1−/y cells (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

PDGF induces SSH1L serine dephosphorylation of 14-3-3 binding motifs in wt but not in Nox1−/y cells. Both wt and Nox1−/y VSMCs were incubated with either vehicle or PDGF (10 ng/ml for 15 min). After immunoprecipitation of SSH1L, the membrane was immunoblotted for the phosphor-Ser 14-3-3 binding motif. Bars represent mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

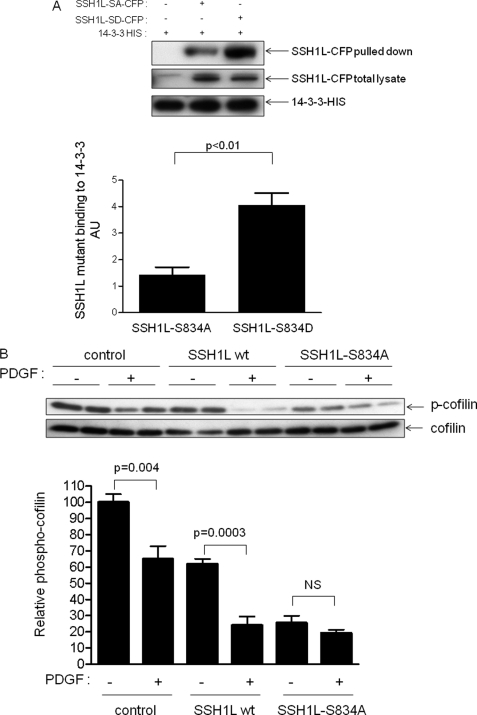

Using software analysis (Prosite software), we found a primary putative phospho-serine 14-3-3 binding motif that contains the sequence R-X-X-S*-X-P, which harbors the serine 834. We then generated two mutants: the phospho-mimetic (S834D) and the phospho-deficient (S834A) mutants. As we predicted, the phosphorylation at this site has a major role in SSH1L binding to 14-3-3 (Fig. 5A). The phosphomimetic mutant has a greater binding capacity for 14-3-3 than does the phosphor-deficient mutant. Theoretically, if this site is the one that mediates SSH1L/14-3-3 protein interaction, the non-phosphorylatable mutant will not be inhibited by 14-3-3 and will cause constitutive cofilin dephosphorylation. In Fig. 5B, we show that transfection of VSMCs with SSH1L-wt enhances both basal and PDGF-stimulated cofilin dephosphorylation, as expected. We are using cofilin as a readout because we have previously shown that, after PDGF treatment, levels of p-cofilin track SSH1L and not LIMK activity in these cells (2). In contrast, SSH1L-S834A acts as a constitutively active enzyme basally, and PDGF causes no further dephosphorylation of cofilin. These results suggest that phosphorylation of serine 834 maintains SSH1L in an inactive state in VSMCs, and that dephosphorylation is required for activation.

FIGURE 5.

Serine 834 phosphorylation governs SSH1L binding to 14-3-3 and phosphatase activity. A, effect of serine 834 phosphorylation in the binding to 14-3-3. HEK cells were cotransfected with 14-3-3-HIS and either SSH1L-S834D-CFP or SSH1L-S834A-CFP. After 24 h, His-tagged proteins were pulled down using dynabeads and the amount of SSH1L was analyzed using an antibody against CFP. Bars represent mean ± S.E. average of four independent experiments. B, SSH1L-S834A acts as a constitutively active enzyme. VSMCs were transfected with GFP vector, wt SSH1L, or SSH1L-S834A by electroporation. Cells were then treated with vehicle or PDGF (10 ng/ml for 15 min). Bars represent mean ± S.E. average from three independent experiments.

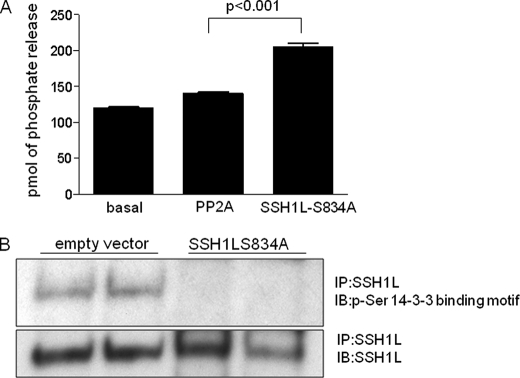

Because SSH1L dephosphorylation/activation is clearly Nox1-dependent in VSMCs treated with PDGF (Figs. 1 and 4), we sought to investigate the identity of the phosphatase involved in this mechanism. At first, we studied the sensitivity of PDGF-induced SSH1L activation to several inhibitors. Pretreatment of VSMCs with okadaic acid or cyclosporin A has no effect on cofilin dephosphorylation, ruling out the participation of phosphatases PP1/PP2A and PP2B, respectively (data not shown). We also used cells from PP2C or PP2B knock-out animals, but saw no effect on PDGF-induced cofilin dephosphorylation (data not shown). Previous work showed that the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor vanadate attenuated SSH1L activity (22). Because the putative phosphatase clearly dephosphorylates phospho-serine residues (Fig. 4), this raises the possibility that a dual specificity phosphatase leads to the dephosphorylation of serine 834 in SSH1L. Because SSH1L is one of the few dual phosphatases that has been described to be activated by PDGF, we explored the possibility that SSH1L dephosphorylates itself. Indeed, SSH1L-S834A, the constitutively active mutant, dephosphorylates endogenous SSH1L but not PP2A in vitro (Fig. 6A) and in vivo (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

SSH1L is auto-dephosphorylated. HEK cells were transfected by electroporation with either empty vector or vector expressing SSH1L-S834A-CFP, 24 h before the experiments. A, ability of PP2A or SSH1L-S834A to dephosphorylate endogenous SSH1L was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures” using endogenous SSH1L as a substrate. B, endogenous total SSH1L protein was immunoprecipitated and the amount of phospho-SSH1L was evaluated using specific antibodies against the phospho-Ser-14-3-3 binding motif, the membrane was then reblotted to verify that the same amount of total SSH1L was pulled down in each lane. Blot is representative of four independent experiments.

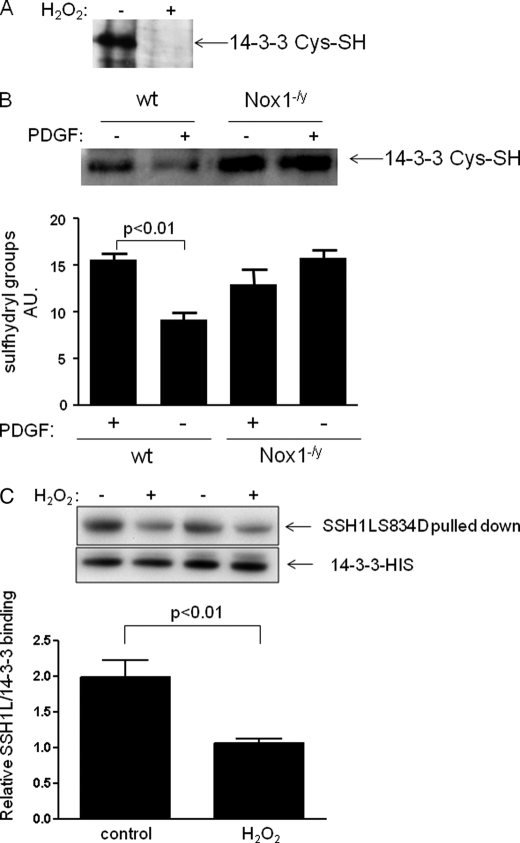

Disruption of the binding of 14-3-3 with SSH1L via serine 834 dephosphorylation thus seems to be a critical step for SSH1L activation in VSMC. Considering that SSH1L is constitutively phosphorylated in VSMC with undetectable endogenous activity (2), and that deletion of Nox1 prevents SSH1L dephosphorylation by PDGF, an additional phosphatase-independent step must be required to allow autodephosphorylation of SSH1L to occur. We hypothesized that this initial step is Nox1-dependent oxidation of 14-3-3. In support of this hypothesis, others have observed that angiotensin II (a Nox1 agonist) can induce SSH1L/14-3-3 complex disruption by 14-3-3 oxidation (10). To determine if PDGF induces 14-3-3 oxidation in VSMC, we labeled reduced cysteine residues using 5IAF, so the reduction in band intensity indicates increased oxidation. We confirmed the presence of oxidable cysteine groups in 14-3-3 (Fig. 7A) and that, indeed, 14-3-3 is oxidized after 15 min of PDGF treatment in wild type but not in Nox1−/y cells (Fig. 7B). This increased oxidation correlates with the increase in activity observed in Fig. 1, supporting a role for 14-3-3 oxidation in the Nox1-mediated PDGF-induced SSH1L activation mechanism in VSMCs. Finally, and in order to evaluate the unique contribution of H2O2 to the SSH1L/14-3-3 complex disruption, we quantified the binding of 14-3-3 to the phospho-mimetic mutant before and after H2O2 treatment. Fig. 7C shows that 14-3-3 oxidation by itself reduces the binding to SSH1L, and together with the fact that Nox1 is required for 14-3-3 oxidation (Fig. 7B), indicates that it is Nox1-derived H2O2 that induces complex disruption.

FIGURE 7.

14-3-3 oxidation induces SSH1L/14-3-3 complex disruption. A, 14-3-3 contains oxidable cysteine residues. The detection of sulfyhydryl groups was performed under anaerobic conditions using 5-IAF as described under “Experimental Procedures” after 15 min of 100 μm of H2O2 treatment or control conditions. B, 14-3-3 is oxidized by PDGF in Nox1-dependent manner. Cells from wild type and Nox1−/y animals were serum deprived for 48 h and then stimulated with PDGF (10 ng/ml) for 15 min, and sulfyhydryl groups were quantified as described above. Bars represent mean ± S.E. average from four independent experiments. C, effect of H2O2 on the 14-3-3 binding capacity to SSH1L. HEK cells were transfected by electroporation with 14-3-3-HIS and SSH1L-S834D-CFP. After 24 h cells were treated with H2O2 for 30 min and His-labeled proteins were pulled down. The binding of SSH1L in each case was quantified using a specific antibody that recognized CFP.

DISCUSSION

Our previous work showed that SSH1IL phosphatase is required for PDGF-induced migration in VSMC (2). In the present study, we now describe several important observations concerning the mechanism of SSH1L phosphatase activation by PDGF in VSMC. We found that the major mechanism of SSH1L activation relies on the Nox1-dependent auto-dephosphorylation of serine 834, which is harbored in a 14-3-3 binding motif. Dephosphorylation of this site releases SSH1L from its inhibitory interaction with 14-3-3, thus activating it.

It is well established that ROS, such as H2O2, play important roles as signaling molecules in all types of vascular cells (23). In particular, it has been shown that H2O2 is required for VSMC migration induced by PDGF (14). However, the exact participation of ROS in diverse signaling pathways is far from clear.

The sensitivity of cofilin dephosphorylation to H2O2 has been previously reported to be both positive and negative. On one hand, in other cell types, H2O2 at sub-millimolar concentrations induces dephosphorylation of cofilin (10, 22), consistent with our findings in VSMCs. On the other hand, Eiseleret al. (16) reported that 10 mm H2O2 induces phosphorylation of cofilin in a protein kinase d-dependent manner. In our experience, concentrations higher than 200 μm H2O2 in VSMC cause apoptosis (24); consequently, the interpretation of results obtained with high concentrations of oxidant is complex. From our point of view, dephosphorylation and activation of cofilin using moderate concentrations of exogenous H2O2 seems to be physiologically relevant, since these conditions recapitulate cofilin activation in wt cells treated with PDGF, and cells derived from Nox1−/y animals have lesser amounts of dephosphorylated/active cofilin (15).

Although there are some contradictory reports (25), the current dogma is that phosphatases are inactivated by ROS. This is true when the modification is the consequence of direct interaction of ROS with the protein phosphatase, resulting in oxidation of redox-sensitive cysteine residues in the active site of the enzyme, a mechanism that has been extensively studied in the case of tyrosine phosphatases (26). However, as we describe in the present work, there are other mechanisms by which ROS can influence enzyme activity, for example by regulating protein-protein interactions. In fact, by disrupting an inhibitory complex, such a step could facilitate the activation of protein phosphatases.

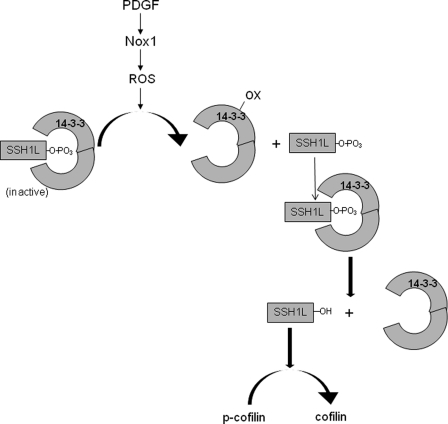

Our data support this notion and suggest that oxidation of 14-3-3 is a critical step in the pathway leading to cofilin activation. Indeed, 14-3-3 was previously reported to be a target of thioredoxin, peroxiredoxin and redox-sensitive selenium-containing protein (27–29). Notably, CD81 association with 14-3-3 was shown to be regulated by a redox-dependent palmitoylation (30). Our own data show that treatment with PDGF leads to oxidation of 14-3-3 (Fig. 7). This is in agreement with a recent report showing the ability of Ang II (a known Nox1 agonist) to oxidize 14-3-3 (10). Once oxidation of 14-3-3 occurs, SSH1L can dephosphorylate and therefore activate itself. Thus, in this case, activation, rather than inhibition of a phosphatase, is dependent upon ROS production. We conceptualize our findings in a model shown in Fig. 8.

FIGURE 8.

Model of PDGF-induced SSH1L activation in VSMC. PDGF stimulates Nox 1 to produce ROS. The Nox1-produced ROS then oxidizes 14-3-3, releasing SSH1L phosphatase which now can dephoshorylate other SSH1L molecules, facilitating the disruption of the inhibitory complex with 14-3-3 and thus increasing SSH1L phosphatase activity.

In VSMCs, the activity of SSH1L is largely governed by phosphorylation in the 14-3-3 binding motif that harbors the serine in position 834. PDGF induces the dephosphorylation of this site in order to disrupt the inhibitory complex between SSH1L and 14-3-3. It remains unclear if this is a universal activation mechanism for this enzyme in VSMCs, since no other agonists have yet been reported to activate SSH1L in this cell type. Moreover, we do not know if additional post-translational modifications induced by PDGF are required to fully activate this phosphatase in VSMCs. However, the fact that the SSH1L-S834A mutant exhibits constitutive activity seems to indicate that, in VSMCs, SSH1L does not require further modifications for full activity. Finally, it is plausible that part of the mechanism of regulation of SSH1L activity by 14-3-3 binding is its targeting to a different subcellular localization. This is an interesting hypothesis that requires further analysis.

In the past, a series of studies have established that serines 937 and 978 participate in SSH1L activation by calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation (12, 16, 31). However, in VSMCs, PDGF-dependent dephosphorylation of cofilin is calcineurin-independent (not shown). More importantly, these sites are not recognized by the antibody used in the present study, which only detects phosphoserines in 14-3-3 consensus sites (R-X-X-S*-X-P). Thus, serine 834 belongs to a distinct signaling pathway of SSH1L activation initiated by PDGF.

In addition to identifying this new mechanism of redox control of the upstream pathways leading to SSH1L activation and the subsequent cofilin activation, a major finding of our study is the identification of a novel auto-dephosphorylation mechanism. Although, the capacity of SSH1L of undergo auto-dephosphorylation has not been described, this mechanism is not unique, and has been reported to be used for other phosphatases such as PTEN (32) and for the insulin receptor (33).

Taken together, our data support the concept that PDGF induces SSH1L activation in VSMCs by a novel mechanism that involves Nox1-mediated oxidation of 14-3-3 and Ser834-SSH1L auto-dephosphorylation in a 14-3-3 consensus binding motif. These findings suggest specific therapeutic targets for diseases in which VSMC migration plays a role.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kenzaku Mizuno from Tohoku University, Japan, Haian Fu, Jennifer Gooch, and Holly Williams from Emory University for their contribution to this work.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL93115, HL058863, and HL007745.

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cell

- 5-IAF

- 5-iodoacetamido fluorescein

- SSH

- slingshot

- PDGF

- platelet-derived growth factor

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schwartz S. M. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 99, 2814–2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. San Martín A., Lee M. Y., Williams H. C., Mizuno K., Lassègue B., Griendling K. K. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Janssens V., Goris J. (2001) Biochem. J. 353, 417–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yaffe M. B. (2002) FEBS Lett. 513, 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fu H., Subramanian R. R., Masters S. C. (2000) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 40, 617–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Autieri M. V., Carbone C. J. (1999) DNA Cell Biol. 18, 555–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Autieri M. V., Haines D. S., Romanic A. M., Ohlstein E. H. (1996) Cell Growth Differ. 7, 1453–1460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ellis J. J., Valencia T. G., Zeng H., Roberts L. D., Deaton R. A., Grant S. R. (2003) Mol. Cell Biochem. 242, 153–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henriksson M. L., Francis M. S., Peden A., Aili M., Stefansson K., Palmer R., Aitken A., Hallberg B. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 4921–4929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim J. S., Huang T. Y., Bokoch G. M. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2650–2660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kligys K., Claiborne J. N., DeBiase P. J., Hopkinson S. B., Wu Y., Mizuno K., Jones J. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32520–32528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nagata-Ohashi K., Ohta Y., Goto K., Chiba S., Mori R., Nishita M., Ohashi K., Kousaka K., Iwamatsu A., Niwa R., Uemura T., Mizuno K. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 165, 465–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soosairajah J., Maiti S., Wiggan O., Sarmiere P., Moussi N., Sarcevic B., Sampath R., Bamburg J. R., Bernard O. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 473–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sundaresan M., Yu Z. X., Ferrans V. J., Irani K., Finkel T. (1995) Science 270, 296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee M. Y., San Martin A., Mehta P. K., Dikalova A. E., Garrido A. M., Lyons E., Krause K. H., Banfi B., Lambeth J. D., Lassègue B., Griendling K. K. (2009) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 480–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eiseler T., Döppler H., Yan I. K., Kitatani K., Mizuno K., Storz P. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 545–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kligys K., Yao J., Yu D., Jones J. C. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 383, 450–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu Y., Kwon K. S., Rhee S. G. (1998) FEBS Lett. 440, 111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brandes R. P., Viedt C., Nguyen K., Beer S., Kreuzer J., Busse R., Görlach A. (2001) Thromb. Haemost 85, 1104–1110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weber D. S., Taniyama Y., Rocic P., Seshiah P. N., Dechert M. A., Gerthoffer W. T., Griendling K. K. (2004) Circ. Res. 94, 1219–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cross J. V., Templeton D. J. (2006) Antioxid Redox Signal 8, 1819–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee C. K., Park H. J., So H. H., Kim H. J., Lee K. S., Choi W. S., Lee H. M., Won K. J., Yoon T. J., Park T. K., Kim B. (2006) Proteomics 6, 6455–6475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Griendling K. K., Sorescu D., Lassègue B., Ushio-Fukai M. (2000) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 2175–2183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deshpande N. N., Sorescu D., Seshiah P., Ushio-Fukai M., Akers M., Yin Q., Griendling K. K. (2002) Antioxid Redox Signal 4, 845–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sommer D., Coleman S., Swanson S. A., Stemmer P. M. (2002) Arch Biochem. Biophys 404, 271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tonks N. K. (2005) Cell 121, 667–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dikiy A., Novoselov S. V., Fomenko D. E., Sengupta A., Carlson B. A., Cerny R. L., Ginalski K., Grishin N. V., Hatfield D. L., Gladyshev V. N. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 6871–6882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meek S. E., Lane W. S., Piwnica-Worms H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32046–32054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pozuelo Rubio M., Geraghty K. M., Wong B. H., Wood N. T., Campbell D. G., Morrice N., Mackintosh C. (2004) Biochem. J. 379, 395–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clark K. L., Oelke A., Johnson M. E., Eilert K. D., Simpson P. C., Todd S. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19401–19406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peterburs P., Heering J., Link G., Pfizenmaier K., Olayioye M. A., Hausser A. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 5634–5638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raftopoulou M., Etienne-Manneville S., Self A., Nicholls S., Hall A. (2004) Science 303, 1179–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gruppuso P. A., Boylan J. M., Levine B. A., Ellis L. (1992) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 189, 1457–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ohmi K., Masuda T., Yamaguchi H., Sakurai T., Kudo Y., Katsuki M., Nonomura Y. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238, 154–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]