Abstract

Factor B is a zymogen that carries the catalytic site of the complement alternative pathway C3 convertase. During convertase assembly, factor B associates with C3b and Mg2+ forming a pro-convertase C3bB(Mg2+) that is cleaved at a single factor B site by factor D. In free factor B, a pair of salt bridges binds the Arg234 side chain to Glu446 and to Glu207, forming a double latch structure that sequesters the scissile bond (between Arg234 and Lys235) and minimizes its unproductive cleavage. It is unknown how the double latch is released in the pro-convertase. Here, we introduce single amino acid substitutions into factor B that preclude one or both of the Arg234 salt bridges, and we examine their impact on several different pro-convertase complexes. Our results indicate that loss of the Arg234-Glu446 salt bridge partially stabilizes C3bB(Mg2+). Loss of the Arg234-Glu207 salt bridge has lesser effects. We propose that when factor B first associates with C3b, it bears two intact Arg234 salt bridges. The complex rapidly dissociates unless the Arg234-Glu446 salt bridge is released whereupon conformational changes occur that activate the metal ion-dependent adhesion site and partially stabilize the complex. The remaining salt bridge is then released, exposing the scissile bond and permitting factor D cleavage.

Keywords: Complement, Convertases, Protein Assembly, Protein Processing, Protein Stability, Serine Protease, Alternative Pathway, Factor B, Factor D

Introduction

The complement system plays major roles in innate and adaptive immunity. Complement marks microbial pathogens for opsonization and clearance or for lysis and plays a key role in the identification and removal of damaged tissue and other potentially dangerous biological debris (1). It modulates the antibody repertoire (2, 3), and it plays a pivotal role in the normal activity of regulatory T cells (4). Complement activity is also critical in the pathogenesis of many diseases and injury states (5). Therapeutic agents designed to inhibit harmful complement activity have begun to emerge in the clinical environment (6).

Complement is activated by three pathways: the classical pathway, the lectin pathway, and the alternative pathway (AP)2 (1, 7). Each pathway directs the assembly of the C3 convertases, serine proteases that cleave the abundant plasma protein C3 to form C3b, an opsonin that marks potential targets for clearance and/or lysis, and C3a, a potent anaphylactic agent that promotes multiple inflammatory reactions. The AP also serves to amplify the activity of all three pathways, promoting a rapid and robust response. Fluid phase and membrane-bound complement regulators protect host tissues from complement-mediated damage (8).

Factor B is a single chain glycoprotein, composed of an amino-terminal region of three complement control protein domains, a 40-amino acid linker region, a single von Willebrand factor type A domain (VWA), and a carboxyl-terminal serine protease domain (see Fig. 1A) (9). Factor B binds to C3b in the presence of Mg2+, forming a transient complex (t½ ∼5 s) (10, 11) that is cleaved by factor D at a single site in the linker region to generate the AP C3 convertase, C3bBb(Mg2+) (t½ ∼90 s) (12, 13). During this process a metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS) is formed at the apex of the VWA domain and mediates Mg2+-dependent C3b binding, and an exosite is formed at the VWA-serine protease domain interface and mediates factor D binding (14).

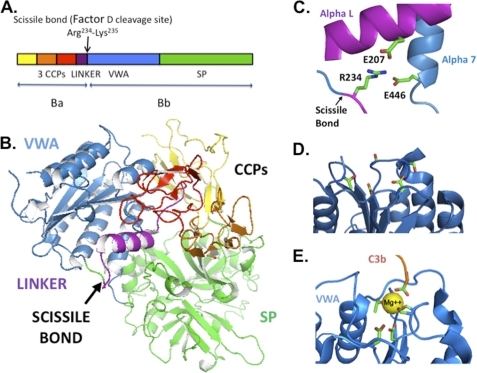

FIGURE 1.

Factor B structure. A, scissile bond lying between the linker region and the VWA domain in the factor B primary sequence (9). CCP, complement control protein repeat. B, factor B three-dimensional structure (15). C, scissile bond sequestered by salt bridges that bind the Arg234 side chain to Glu207 and Glu446 (15). D, factor B VWA apex with its cation-free MIDAS (15). E, C3bBb VWA apex with MIDAS occupied with Mg2+ that is coordinated by five conserved VWA side chains plus the carboxyl terminus of C3b (11). The coordination residues are shown as stick figures. Coordinates of factor B and of C3bBb stabilized by the staphylococcal complement inhibitor SCIN were obtained from the Protein Data Bank, accession numbers 2OK5 and 2WIN, respectively. Molecular structures are illustrated using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (42).

In free factor B, a pair of salt bridges connects the Arg234 side chain to Glu207 of the linker region and Glu446 of the VWA domain in a “locked” conformation (Fig. 1, B and C) (15). The salt bridges sequester the scissile bond (between Arg234 and Lys235) and prevent unproductive cleavage of factor B by circulating serine proteases (16). It is not known how the double latch structure is opened to permit factor D cleavage of the scissile bond in the short lived C3bB(Mg2+) complex.

Here, we characterize the properties of factor B mutations that preclude one or both of the Arg234 salt bridges. We examine their effects on the assembly and stability of the pro-convertase C3bB(Mg2+). Our analyses indicate that the release of the Arg234 salt bridges partially stabilizes the C3bB(Mg2+) complex and that this effect is due predominantly to loss of the Arg234-Glu446 bond. This result was greatly diminished in the case of CVFB(Mg2+), a pro-convertase that incorporates the C3b homolog cobra venom factor (CVF) in place of C3b and is 100-fold less sensitive to factor D than is C3bB(Mg2+) (17). It was also absent in the case of C3bB(Ni2+), a pro-convertase in which the salt bridges are spontaneously released. From our observations we propose a specific order of molecular events that accounts for the release of the Arg234 salt bridges, formation of the MIDAS and factor D exosite, and the cleavage of the scissile bond by factor D during the assembly of the AP convertase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Purified native complement proteins (human C3b, CVF, factor B, factor D) and antibody-sensitized sheep erythrocytes were obtained from CompTech, Tyler, TX. N-Hydroxysuccinimide, EDAC, and ethanolamine solutions were purchased from GE Healthcare and stored at −20 °C.

Production of Factor B Mutants

Recombinant factor B proteins were produced with a previously described factor B cDNA cloned in pSG5 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) expression vector (18). Mutations were introduced into the cDNA sequence by the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method (Stratagene). Some multiple mutations were constructed using previously reported single and double mutations. Human 293T kidney cells were transfected in serum-free medium utilizing Opti-MEM (Invitrogen catalog no. 31985-070) supplemented with 4 mm l-glutamine. Cell supernatants were collected, treated with benzamidine-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences catalog no. 17-5123-10) to remove nonspecific proteases, and dialyzed and stored in phosphate buffer (11 mm Na2HPO4, 1.8 mm NaH2PO4, pH 7.4) supplemented with 25 mm NaCl.

Recombinant factor B was quantitated by ELISA with mouse anti-human Ba mAb (Quidel, San Diego, CA) for capture and goat anti-human factor B polyclonal antibody (catalog no. 80264; Diasorin, Stillwater, MN) for detection. Recombinant proteins were quantified by ELISA and examined by Western blotting. A factor B-dependent hemolysis assay (18) was used to determine complement activity. We have numbered the factor B residues based on the amino acid sequence of the mature protein (9). The D254G mutation has also been referred to as D279G based on the inclusion of the N-terminal signal sequence (19).

Surface Plasmon Resonance Analysis

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) methodology was conducted with a BIAcore 2000 instrument using the manufacturer's software package (BIAcore, Piscataway, NJ). CM5 sensor chips (BIAcore catalog no. BR-1000-14) were used throughout with Mg2+-HEPES running buffer (filtered and degassed 10 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.005% Tween 20, pH 7.4). In some cases MgCl2 was replaced with 2 mm NiCl2, 2 mm MnCl2, or 3 mm EDTA. All experiments were carried out at 25 °C.

Biosensor flow paths were activated with a fresh 1:1 mixture of 0.05 m N-hydroxysuccinimide and 0.2 m EDAC injected at 5 μl/min for 7 min. C3b ligand was then covalently attached to the activated surface: C3b or CVF was dissolved in 10 mm citrate buffer, pH 4.8, at 10 μg/ml and injected in the experimental flow path, at 10 μl/min for 90 s to 3 min. The flow path was then “blocked” by treatment with 1 m ethanolamine, pH 8.5, at 5 μl/min for 7 min. A reference flow path was produced as above but without C3b in the citrate buffer.

Various combinations of native or mutant factor B or native factor D in running buffer were injected at 30 μl/min for varying times using the KINJECT command. Changes in response units, indicative of changes in mass bound to the biosensor surface, were expressed as the difference between the ligand-treated and reference flow paths. Mutant factor B cell supernatant preparations were dialyzed with running buffer before use. Residual C3bB and CVFB complexes were dissociated with EDTA HEPES buffer. Kinetic analyses were performed using the Biaevaluation software package. Kinetic analysis of native plasma-derived factor B yielded a two-state conformational change model similar to those obtained by Harris et al. (10) and by Rooijakkers et al. (11) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Analyses of pro-convertase complexes

All kinetic analyses were performed using a two-state conformational change model.

| Analyte | Bound ligand | kon1 | koff1 | KD | kon2 | koff2 | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m−1 s−1 | s−1 | m | s−1 | s−1 | χ2 | ||

| Recombinant fBa | C3b | 1.8 106 | 0.135 | 7.3 10−8 | 1.1 10−2 | 2.8 10−3 | 0.23 |

| E446V | C3b | 1.0 106 | 0.016 | 1.6 10−8 | 4.4 10−3 | 4.5 10−3 | 0.90 |

| E207A | C3b | 1.9 106 | 0.090 | 4.6 10−8 | 5.4 10−3 | 7.2 10−3 | 0.84 |

| Recombinant fB | CVF | 0.8 106 | 0.038 | 4.6 10−8 | 1.8 10−3 | 3.3 10−3 | 0.83 |

| E446V | CVF | 0.7 106 | 0.020 | 2.9 10−8 | 2.9 10−3 | 2.7 10−5 | 0.74 |

| Plasma fB This investigation | C3b | 7.9 104 | 0.111 | 1.4 10−6 | 4.7 10−3 | 6.2 10−3 | 2.9 |

| Plasma fB (Ref. 10) | C3b | 1.4 104 | 0.12 | 8.5 10−6 | 5.5 10−3 | 1.8 10−3 | 4.2 |

| Plasma fB (Ref. 11) | C3b | 2.9 104 | 0.11 | 3.8 10−6 | 1.1 10−2 | 2.6 10−3 | 2.9b |

| Plasma fD | C3bBc | 1.9 105 | 0.11 | 5.6 10−7 | 7.6 10−3 | 1.0 10−2 | 2.3 |

a The disparity in KD between plasma fB and recombinant fB is due predominantly to the difference in their kon1 values (KD = koff1/kon1). This could be the result of differential glycosylation and/or greater homogeneity of the recombinant protein versus the plasma protein. Importantly, the conclusions of this study are critically dependent on koff1 values, and the koff1 values obtained for recombinant fB and plasma fB are in agreement and consistent with the published values (above). Thus, the differences in kon1 between plasma fB and recombinant fB, while of note, do not affect the major findings of this study.

b Error determined by alternative method.

c C3bB(Mg2+) complex incorporating the factor BD254G, N260D, 233AAA mutation.

RESULTS

Impact of the Arg234 Salt Bridges on C3bB(Mg2+) Pro-convertase Complexes

The factor B Arg234 salt bridges protect the scissile bond and so must be broken to permit factor D cleavage (Fig. 1C). In this study we used site-directed mutagenesis to generate factor B proteins that lack either one or both salt bridges to characterize the C3bB complexes that form without them. Mutations were introduced in a previously described factor B cDNA, and recombinant proteins were produced by transient transfection of human 293T kidney cells. Recombinant proteins were quantified by ELISA and examined further by Western blot analysis (see “Experimental Procedures”).

We first examined mutations that replace the Arg234 residue, thus precluding both protective salt bridges and also altering the factor D cleavage site, producing hemolytically inactive proteins. Purified C3b was bound to a biosensor surface and subsequently treated in the presence of Mg2+ with a factor B single amino acid substitution, R234A. As shown in Fig. 2A, R234A increased C3b binding up to 10-fold compared with wild-type native and recombinant factor B. The resulting C3bB(Mg2+) complexes rapidly dissociated in the presence of EDTA (data not shown), characteristic of wild-type C3bB(Mg2+) but not of C3bBb(Mg2+) (10, 20). Greater than 5-fold increases in C3b binding were observed with the single amino acid substitution R234N and with 233AAA, a substitution that replaces three amino acids at the cleavage site (K233A/R234A/K235A) (19) (Fig. 2B).

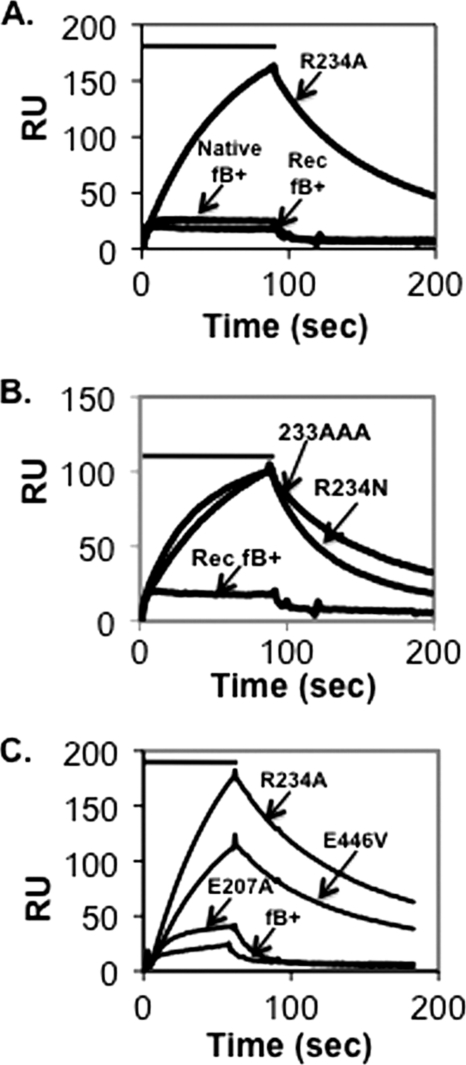

FIGURE 2.

Assembly and dissociation of C3bB(Mg2+) on a C3b-coated biosensor surface. A, C3b (1860 response units (RU)) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 90 s (indicated by the bar above the profiles) with 5 μg/ml wild-type plasma-derived native factor B, recombinant factor B, or factor B R234A in Mg2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0. The peak of the R234A profile represents complexes formed with 17% of the surface-bound C3b. Residual C3bB complexes were dissociated with EDTA HEPES buffer between factor B treatments. B, C3b-coated biosensor surface in A was treated as above with 5 μg/ml factor B R234N, factor B 233AAA, and recombinant factor B. C, C3b (2890 response units) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 60 s with 2 μg/ml factor B R234A, factor B E446V, factor B E207A, or wild-type recombinant factor B followed by buffer alone. The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0. The peak of the R234A profile represents complexes formed with 12% of the surface-bound C3b.

We next examined the effects of amino acid substitutions which preclude one Arg234 salt bridge at a time. Two mutations were selected: E207A (removing the side chain joining Arg234 to the linker region) and E446V (removing the side chain joining Arg234 to the VWA domain) (see Fig. 1C). Both mutant proteins were hemolytically active and in that respect not statistically different from the wild-type recombinant protein (E446V, 67 ± 10% of wild type; E207A, 104 ± 30% of wild type; n = 5).

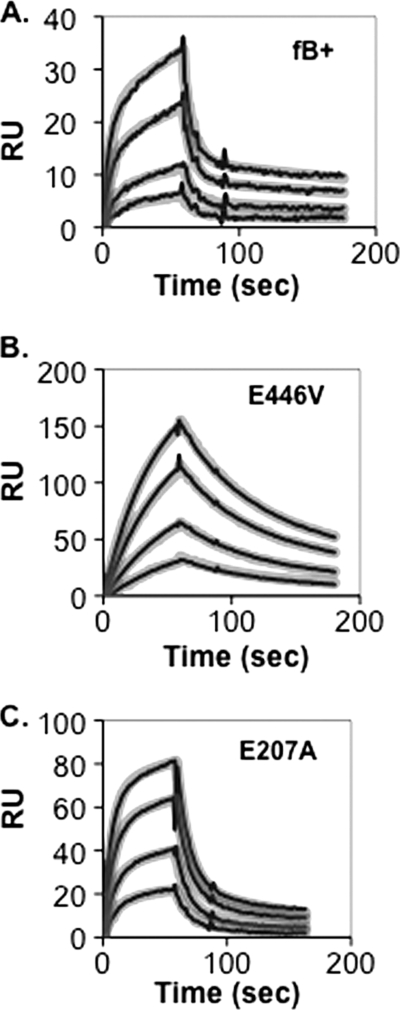

Using the SPR methodology, we compared the C3b binding activity of E207A and of E446V with the R234A substitution and with wild-type factor B. The E446V mutation resulted in accentuated Mg2+-dependent C3b binding similar to the R234A substitution (Fig. 2C). The effect was much less prominent in the case of E207A. Further insight was obtained through a detailed kinetic analysis of the two mutants and their wild-type recombinant parent (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Interaction of all three proteins with the C3b ligand in the presence of Mg2+ best conformed to a two-state conformational change model, as reported previously by Harris et al. for factor B derived from human plasma (10). Wild-type recombinant factor B had the lowest affinity for C3b (KD = 73 nm), E207A somewhat greater affinity for C3b (KD = 46 nm), and E446V had the greatest affinity for C3b (KD = 16 nm). These differences in affinity were mainly due to differences in C3bB stability: C3bB complex that incorporated recombinant wild-type factor B was least stable (koff1 = 0.135 s−1; t½ ∼5 s), those that incorporated E207A were about 50% more stable than wild type (koff1 = 0.090 s−1; t½ ∼8 s), and those that incorporated E446V were 8-fold more stable than wild type (koff1 = 0.016 s−1; t½ ∼43 s).

FIGURE 3.

Kinetic analysis of C3bB(Mg2+) assembly and dissociation on a C3b-coated biosensor surface. C3b (2890 response units (RU)) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 60 s with various concentrations of recombinant factor B (A), factor B E446V (B), or factor B E207A (C) in Mg2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. The resulting profiles were subjected to kinetic analysis using a two-state conformational change model (10) and the BIAevaluation software. The thin black lines represent the original data profiles, and the thick gray lines represent the global best fit (see calculated kinetic constants in Table 1).

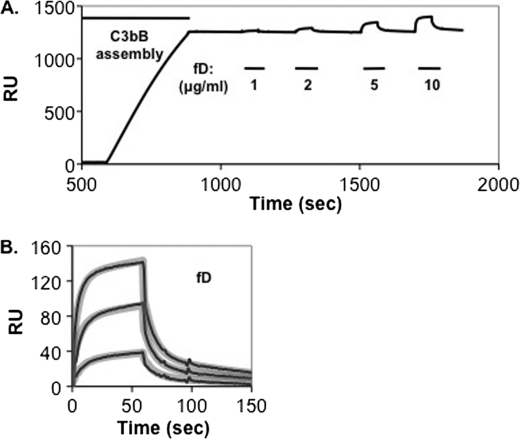

Previous studies by Forneris et al. have established that in the pro-convertase complex, an essential factor D-binding site (exosite), is formed between the VWA and serine protease domains when the two factor B Arg234 salt bridges are released (14). The exosite can be readily detected by SPR analysis if the factor B D254G/N260D double gain-of-function mutation is used to stabilize C3bB(Mg2+) on the biosensor and factor D cleavage is inhibited (14). We combined the D254G/N260D factor B mutations with the 233AAA mutation that precludes both salt bridges and confers factor D resistance. We pretreated C3b that had been bound to a biosensor surface with the mutant factor B protein in the presence of Mg2+, forming a stable C3bB(Mg2+) complex (Fig. 4A). We then treated the resulting C3bB(Mg2+) complexes with various concentrations of factor D. Factor D bound readily to the C3bB(Mg2+) complexes (Fig. 4 and Table 1). We conclude that whether the Arg234 salt bridges are released during convertase assembly or precluded by mutation, a functional factor D exosite can form.

FIGURE 4.

Interaction of factor D with stable surface-bound C3bB(Mg2+). A., C3b (8514 response units (RU)) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 300 s with 2 μg/ml factor B D254G/N260D/233AAA in Mg2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. Complexes were then treated for 60 s with different concentrations of factor D (indicated by the bars below the profile). The profile indicates stable C3bB complexes formed with 29% of the surface-bound C3b and the maximum C3bBD complexes formed with 44% of the surface-bound C3bB. B, profiles in A of factor D interactions with C3bB were aligned at t = 0 and subjected to kinetic analysis using a two-state conformational change model (10) and the BIAevaluation software. The thin black lines represent the original data profiles, and the thick gray lines represent the global best fit (see calculated kinetic constants in Table 1).

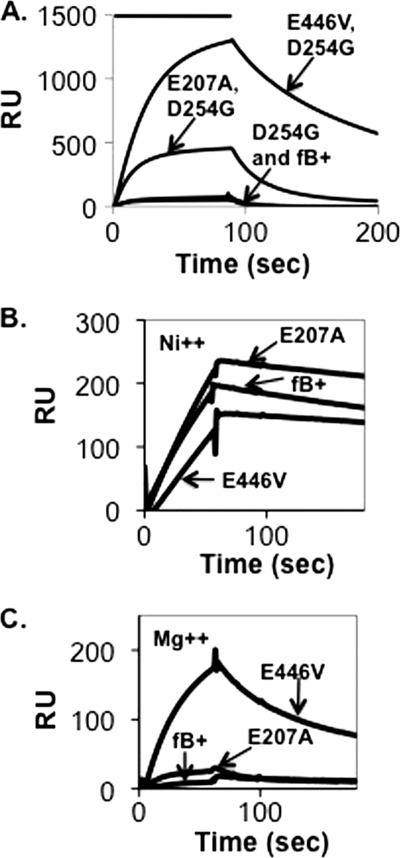

Rodriguez de Cordoba and his collaborators have examined C3bB complexes using single particle electron microscopy (EM) (21, 22). Two C3bB complexes were chosen for their analysis based on added stability: C3BD234G(Mg2+), incorporating the factor B D254G gain-of-function mutation (19), and C3B(Ni2+) (23). Two C3bB conformations in apparent equilibrium were described: a “closed” conformation in which the Arg234 salt bridges are intact and an “open” conformation in which the Arg234 salt bridges are released. In the case of C3BD234G(Mg2+), 35% of the complexes were in the closed conformation (22). In contrast, in the case of C3bB(Ni2+), only 2% of the complexes were closed (21). From these observations we expected that the introduction of either the R234A or E446V mutation with the D234G mutation would increase factor B affinity for C3b by promoting open conformations at the expense of closed conformations. To test this prediction we constructed a series of double mutants: R234A/D254G, E446V/D254G, and E207A/D254G. We then compared the double mutants with the D254G parent (Fig. 5A). The double R234A and E446V mutations resulted in higher affinity for C3b, consistent with our view. However, we did not expect that R234A or E446V would increase the affinity of factor B for C3b in the presence of Ni2+ because the EM study shows that C3bB(Ni2+) complexes are nearly all open conformations already. Consistent with this prediction, the E446V diminished C3b binding slightly in the presence of Ni2+ (compare Fig. 5, B and C).

FIGURE 5.

Assembly and dissociation of C3bB complexes on a C3b-coated biosensor surface. A, C3b (5942 response units (RU)) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 90 s with 10 μg/ml wild-type recombinant factor B, factor B D254G, factor B E446V/D254G, or factor B E207A/D254G in Mg2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0. The peak of the E446V/D254G profile represents complexes formed with 44% of the surface-bound C3b. B, C3b (7205 response units) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 90 s with 1 μg/ml wild-type recombinant factor B or factor B E446V in Ni2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. The peak of the E446V profile represents complexes formed with 10% of the surface-bound C3b. The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0. C, the C3b-coated biosensor shown in A was treated for 90 s with 1 μg/ml wild-type recombinant factor B or factor B E446V as above but in Mg2+ HEPES buffer.

Impact of the Arg234 Salt Bridges on CVF-Factor B Pro-convertase Complexes

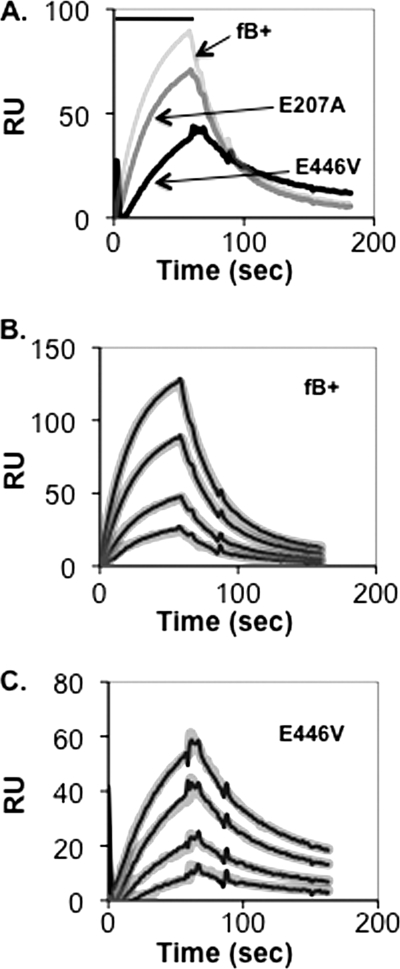

CVF is a C3b homolog that forms an active C3 convertase in concert with factor B, factor D, and divalent cation, CVFBb(Mg2+) (17). CVF is known to bind to factor B with higher affinity than C3b and to produce a highly stable active CVFBb(Mg2+) complex (t½ ∼7 h) (24). The crystal structure of factor B in complex with CVF, CVFB(Mg2+), is regarded as a model for the C3bB closed form because both Arg234 salt bridges remain in place (17). We therefore examined effects of the salt bridge mutants on CVFB(Mg2+) formation. Parallel biosensor flow paths were coated with C3b and CVF, respectively, and treated with the E446V and E207A single mutants and wild-type factor B. Data were analyzed with the two-state conformational change model. The E446V mutant had a modest effect on CVF affinity whereas E207A was similar to wild-type factor B (Fig. 6). Further analysis indicated a KD for CVF/E446V of 29 nm, koff1 of 0.020 s−1, and t½ of ∼35 s, versus KD CVF/wild-type factor B of 46 nm, koff1 of 0.038 s−1, and t½ of ∼18 s (Table 1). In short, whereas loss of the Arg234-Glu446 salt bridge resulted in a 5-fold increase in C3b affinity and an 8-fold increase in C3bB(Mg2+) half-life, it resulted in a <2-fold increase in CVF affinity and CVFB(Mg2+) half-life.

FIGURE 6.

Assembly and dissociation of CVFB(Mg2+) on a CVF-coated biosensor surface. A, CVF (4637 response units (RU)) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 60 s (indicated by the bar above the profiles) in succession with 1 μg/ml wild-type recombinant factor B, factor B E446V, or factor B E207A in Mg2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. The peak of the wild-type recombinant factor B profile represents complexes formed with 4% of the surface-bound CVF. The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0. B and C, CVF (4637 response units) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface (above). At t = 0, the biosensor surface was treated for 60 s (indicated by the bar above the profiles) with various concentrations of recombinant factor B (B) or factor B E446V (C) in Mg2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0 and subjected to kinetic analysis using a two-state conformational change model (10) and the BIAevaluation software. The thin black lines represent the original data profiles, and the thick gray lines represent the global best fit (see values of the resulting kinetic constants in Table 1).

Pro-convertase Complexes Incorporating Mn2+

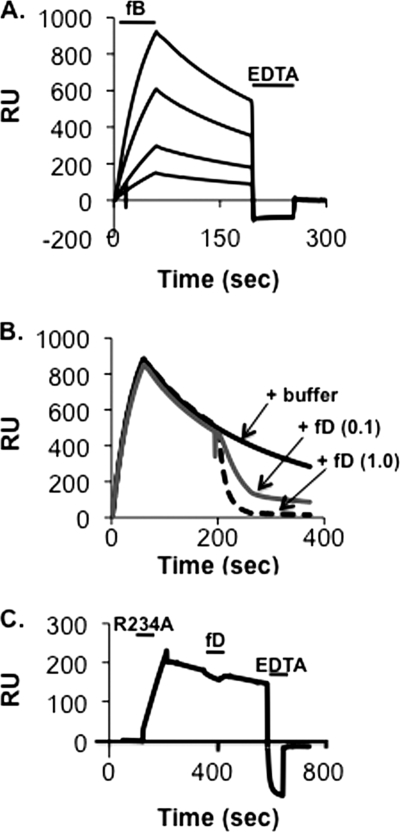

C3bBb(Mg2+) complexes (t½ ∼90 s) (12, 13) are more stable than their C3bB(Mg2+) precursors (t½ ∼5 s; (10, 14). Because the MIDAS is at the center of the C3b:Bb interface, we explored the possibility that the MIDAS structure change during this transition from a low affinity form to a high affinity form. In the case of the integrins, wherein low affinity and high affinity MIDAS structures have been shown, physiologically relevant low affinity MIDAS structures were first observed with the nonphysiological cation Mn2+ (25). Following that lead, we examined the interaction of C3b and wild-type plasma-derived factor B in the presence of Mn2+. We found that Mn2+ can mediate the formation of C3bB (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, treatment of C3bB(Mn2+) complexes with factor D leads to rapid dissociation of the complex without producing a stable C3bBb product (Fig. 7B). Dissociation required cleavage of the scissile bond: C3bB(Mn2+) complexes that incorporate the R234A mutation (and therefore lack the scissile bond) were insensitive to factor D (Fig. 7C). The simplest interpretation of these results is that Mn2+ can stabilize C3bB in a form that is susceptible to factor D cleavage, but Mn2+ cannot stabilize the C3bBb complex that is produced once cleavage has occurred.

FIGURE 7.

Assembly and dissociation of C3bB(Mn2+) and C3bBb(Mn2+) on a C3b-coated biosensor surface. A, C3b (6747 response units (RU)) was covalently attached to a biosensor surface and treated for 60 s in succession with 1, 2, 5, and 10 μg/ml wild-type native factor B in Mn2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. Residual complexes were dissociated with EDTA HEPES buffer (indicated by the second bar). The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0. The maximum peak of the C3bB(Mn2+) profiles represents complexes formed with 27% of the surface-bound C3b. B, the C3b-biosensor surface in A was treated for 60 s with 10 μg/ml wild-type native factor B in Mn2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. At ∼200 s the biosensor surface was treated for 60 s with 1.0 μg/ml factor D, 0.1 μg/ml factor D, or Mn2+ HEPES buffer alone. The resulting profiles were aligned at t = 0. C, the C3b biosensor surface in A was treated was treated for 90 s with 1 μg/ml factor B R234AV in Mn2+ HEPES buffer followed by buffer alone. At ∼300 s the biosensor surface was treated for 60 s with 1.0 μg/ml factor D. At ∼600 s the biosensor surface was treated for 60 s with EDTA HEPES buffer.

DISCUSSION

Although the complement system plays many roles in host defense, it is also a major contributor to harmful inflammatory conditions (26). The AP in particular has been implicated in numerous disease and injury states (5) including age-related macular degeneration (27–31), atypical hemolytic uremic anemia (32–35), rheumatoid arthritis (36), abdominal aortic aneurysms (37), and ischemic reperfusion injury (38). The C3 convertases, C3bBb(Mg2+) and its properdin-stabilized form C3bBbP(Mg2+), are the key enzymes in AP activation and amplification of all of the activation pathways. Strategies designed for the clinical inhibition of the complement AP have focused on the AP components C3b, properdin, factor B, and factor D (6, 39). The detailed characterization of AP C3 convertase assembly has begun to reveal unique pro-convertase structures that could serve as novel AP-specific therapeutic targets (14, 17).

The factor B scissile bond is sequestered by salt bridges that connect the Arg234 side chain to the linker region and to the VWA domain. We have found that factor B mutations that lack the Arg234-Glu446 salt bridge attain a 5–10-fold increase of Mg2+-dependent C3b binding relative to wild-type factor B due primarily to greater complex stability. From these results we hypothesize that in free factor B and in the initial C3bB association, the Arg234-Glu446 salt bridge constrains the VWA domain to low affinity conformations. When the Arg234-Glu446 salt bridge is broken through thermal effects or precluded through mutagenesis, the α7-helix gains conformational freedom that permits the realignment of the VWA domain and activation of the MIDAS, resulting in a higher affinity association of factor B with C3b. Lesser binding effects were seen with a substitution that precludes only the Arg234-Glu207 salt bridge. This finding suggests that although this second salt bridge needs to be broken to permit factor D cleavage, its release results in a much smaller increase in complex stability. Harris et al. (10) have provided kinetic evidence that nascent C3bB(Mg2+) can undergo conformational change resulting in a complex with greater stability (see also Ref. 17). The increase in stability they observed could be primarily due to the breakage of one or both Arg234 salt bridges via thermal effects and the subsequent activation of the MIDAS.

Although free factor B is not cleaved by factor D, it can be cleaved by other trypsin-like serine proteases such as plasmin (16). The double latch structure formed by the Arg234 salt bridges serves to minimize such unproductive activity. Our findings suggest how the double latch is opened during assembly of the C3 convertase. We make the simplifying assumption that releases of the two salt bridges are independent and rapidly reversible events, each driven by thermal effects. Therefore, in free factor B, the probability that both latches are open (and the scissile bond is vulnerable to protease activity) is very low. However, in the pro-convertase, stabilization of the pro-convertase with one latch open would provide a greater time window for the second latch to open and expose the scissile bond. Thus, we propose that when factor B first associates with C3b, it bears two intact Arg234 salt bridges. The complex rapidly dissociates unless the Arg234-Glu446 salt bridge is released whereupon conformational changes occur that activate the MIDAS and partially stabilize the complex. The remaining salt bridge is then released, exposing the scissile bond and permitting factor D cleavage.

In contrast to C3bB(Mg2+), we found that the assembly of CVFB(Mg2+) complexes was much less affected by the Arg234 salt bridge mutations. The high resolution structural model of CVFB(Mg2+) indicates that the MIDAS can be activated even while the Arg234 salt bridges are in place (17), and so by that accounting, the absence or release of the salt bridges would not have a substantial impact on the stability of the CVFB(Mg2+) complex. The mechanism we propose to facilitate cleavage of factor B in C3bB(Mg2+) would not function fully in CVFB(Mg2+). Consistent with this view, CVFB(Mg2+) is a relatively poor factor D substrate compared with C3bB(Mg2+): factor D cleaves CVF B 100-fold slower than it cleaves C3bB (17). Thus, although CVF and C3b are regarded as homologous in structure (17), they differ in at least one key dynamic aspect. This difference could bear on the functional roles of C3bBb versus CVFBb. C3bBb(Mg2+) is a protective unit whose assembly and function must be rapid and robust to defend against harmful entities, reaching maximum activity in a few minutes, yet relatively unstable and sensitive to negative regulators to achieve a safe reaction end point. In contrast, CVFBb(Mg2+) is highly stable (24) and appears to function to deplete host complement resulting in potentially lethal effects including weakness, hemolysis, and shock.

The VWA domain is a versatile structure found in dozens of cell surface receptors and soluble proteins (40). In several members of the integrin family, a VWA domain (referred to in the integrins as an I domain) undergoes conformational changes that drive signal transmission across the plasma membrane (41). In that case, critical allosteric changes are coupled to the transition of the MIDAS from a low ligand binding affinity state, in which the divalent cation is coordinated by five conserved amino acids side chains at the apex of the domain, to a high affinity state similar to the C3 convertase, in which the same five coordinating residues are joined by an amino acid residue derived from the ligand (Fig. 1E) (11). The x-ray crystallographic studies of the C3 pro-convertase complexes CVFB(Mg2+), C3bB(Ni2+), and C3bBD(Mg2+) have provided similar high affinity models of the MIDAS (14, 17). However, unlike the C3 convertase model that was derived with wild-type factor B, the three pro-convertase models were derived with the factor B double gain-of-function mutation D254G/N260D, a mutation that eliminates the glycan moiety at Asn260, removes the Asp254 side chain from the MIDAS, and promotes C3bB stability (19). Thus, whether the high affinity MIDAS structure seen with the double gain-of-function mutant also mediates wild-type pro-convertase is not known. We propose that the wild-type pro-convertase complex C3bB(Mg2+) can harbor an intermediate MIDAS structure of lesser affinity, possibly lacking the ligand coordination residue (25). This would better account for the increase in complex stability that accompanies the transition from pro-convertase to convertase even with the loss of binding interactions between C3b and the Ba region (10,14). We show here that Mn2+ stabilizes C3bB in a form that is susceptible to factor D cleavage but cannot sustain the C3bBb complex once factor D cleavage occurs (Fig. 7). It is possible that Mn2+ mediates a low affinity form of the MIDAS that cannot sustain the C3bBb complex. A high resolution model of C3bB(Mn2+) could be informative in this regard.

The complement pro-convertases represent an example in which important molecular events are regulated by complex conformational changes. Moreover, they are a promising source of potential therapeutic targets that could be used to address the numerous AP-dependent disease and injury states. Although great progress has been made to delineate the molecular underpinnings of convertase assembly and activity, key aspects remain to be clarified. Our results provide new insight into the dynamics of the scissile bond, the VWA domain, and the MIDAS that occur when the Arg234 salt bridges are released.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Atkinson and Elizabeth Miller for helpful readings of the manuscript, Madonna Bogacki for assistance with the manuscript, and Reed Yokoyama for help constructing the factor B R234A mutation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AI051436 (to D. E. H.).

- AP

- alternative pathway

- CVF

- cobra venom factor

- EDAC

- 1-ethyl-3-(3-diethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

- MIDAS

- metal ion-dependent adhesion site

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- VWA

- von Willebrand factor type A domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ricklin D., Hajishengallis G., Yang K., Lambris J. D. (2010) Nat. Immunol. 11, 785–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fearon D. T., Locksley R. M. (1996) Science 272, 50–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carroll M. C. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 981–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kemper C., Atkinson J. P. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holers V. M. (2008) Immunol. Rev. 223, 300–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ricklin D., Lambris J. D. (2007) Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1265–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volanakis J. E. (1998) in The Human Complement System in Health and Disease (Volanakis J. E., Frank M. M. eds) 10th Ed., pp. 9–32, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liszewski M. K., Atkinson J. P. (1998) in The Human Complement System in Health and Disease (Volanakis J. E., Frank M. M. eds) 10th Ed., pp. 149–166, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mole J. E., Anderson J. K., Davison E. A., Woods D. E. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 3407–3412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris C. L., Abbott R. J., Smith R. A., Morgan B. P., Lea S. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2569–2578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rooijakkers S. H., Wu J., Ruyken M., van Domselaar R., Planken K. L., Tzekou A., Ricklin D., Lambris J. D., Janssen B. J., van Strijp J. A., Gros P. (2009) Nat. Immunol. 10, 721–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Medicus R. G., Götze O., Müller-Eberhard H. J. (1976) J. Exp. Med. 144, 1076–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flierl M. A., Schreiber H., Huber-Lang M. S. (2006) J. Invest. Surg. 19, 255–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forneris F., Ricklin D., Wu J., Tzekou A., Wallace R. S., Lambris J. D., Gros P. (2010) Science 330, 1816–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Milder F. J., Gomes L., Schouten A., Janssen B. J., Huizinga E. G., Romijn R. A., Hemrika W., Roos A., Daha M. R., Gros P. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 224–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taylor F. R., Bixler S. A., Budman J. I., Wen D., Karpusas M., Ryan S. T., Jaworski G. J., Safari-Fard A., Pollard S., Whitty A. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 2849–2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Janssen B. J., Gomes L., Koning R. I., Svergun D. I., Koster A. J., Fritzinger D. C., Vogel C. W., Gros P. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 2469–2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hourcade D. E., Wagner L. M., Oglesby T. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19716–19722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hourcade D. E., Mitchell L. M., Oglesby T. J. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 2906–2911 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu Y., Narayana S. V., Volanakis J. E. (2001) Immunol. Rev. 180, 123–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Torreira E., Tortajada A., Montes T., Rodríguez de Córdoba S., Llorca O. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 882–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Torreira E., Tortajada A., Montes T., Rodríguez de Córdoba S., Llorca O. (2009) J. Immunol. 183, 7347–7351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fishelson Z., Pangburn M. K., Müller-Eberhard H. J. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 7411–7415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vogel C. W., Müller-Eberhard H. J. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 8292–8299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee J. O., Bankston L. A., Arnaout M. A., Liddington R. C. (1995) Structure 3, 1333–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hauptmann G., Tappeiner G., Schifferli J. A. (1988) Immunodefic. Rev. 1, 3–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klein R. J., Zeiss C., Chew E. Y., Tsai J. Y., Sackler R. S., Haynes C., Henning A. K., SanGiovanni J. P., Mane S. M., Mayne S. T., Bracken M. B., Ferris F. L., Ott J., Barnstable C., Hoh J. (2005) Science 308, 385–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edwards A. O., Ritter R., 3rd, Abel K. J., Manning A., Panhuysen C., Farrer L. A. (2005) Science 308, 421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haines J. L., Hauser M. A., Schmidt S., Scott W. K., Olson L. M., Gallins P., Spencer K. L., Kwan S. Y., Noureddine M., Gilbert J. R., Schnetz-Boutaud N., Agarwal A., Postel E. A., Pericak-Vance M. A. (2005) Science 308, 419–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hageman G. S., Anderson D. H., Johnson L. V., Hancox L. S., Taiber A. J., Hardisty L. I., Hageman J. L., Stockman H. A., Borchardt J. D., Gehrs K. M., Smith R. J., Silvestri G., Russell S. R., Klaver C. C., Barbazetto I., Chang S., Yannuzzi L. A., Barile G. R., Merriam J. C., Smith R. T., Olsh A. K., Bergeron J., Zernant J., Merriam J. E., Gold B., Dean M., Allikmets R. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7227–7232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Richards A., Kavanagh D., Atkinson J. P. (2007) Adv. Immunol. 96, 141–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Richards A., Buddles M. R., Donne R. L., Kaplan B. S., Kirk E., Venning M. C., Tielemans C. L., Goodship J. A., Goodship T. H. (2001) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 485–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodship T. H., Liszewski M. K., Kemp E. J., Richards A., Atkinson J. P. (2004) Trends Mol. Med. 10, 226–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zipfel P. F., Skerka C., Caprioli J., Manuelian T., Neumann H. H., Noris M., Remuzzi G. (2001) Int. Immunopharmacol. 1, 461–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kavanagh D., Goodship T. H., Richards A. (2006) Br. Med. Bull. 77–78, 5–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ji H., Ohmura K., Mahmood U., Lee D. M., Hofhuis F. M., Boackle S. A., Takahashi K., Holers V. M., Walport M., Gerard C., Ezekowitz A., Carroll M. C., Brenner M., Weissleder R., Verbeek J. S., Duchatelle V., Degott C., Benoist C., Mathis D. (2002) Immunity 16, 157–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pagano M. B., Zhou H. F., Ennis T. L., Wu X., Lambris J. D., Atkinson J. P., Thompson R. W., Hourcade D. E., Pham C. T. (2009) Circulation 119, 1805–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weisman H. F., Bartow T., Leppo M. K., Marsh H. C., Jr., Carson G. R., Concino M. F., Boyle M. P., Roux K. H., Weisfeldt M. L., Fearon D. T. (1990) Science 249, 146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang Y., Qiao F., Atkinson C., Holers V. M., Tomlinson S. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 8068–8076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Springer T. A. (2006) Structure 14, 1611–1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luo B. H., Carman C. V., Springer T. A. (2007) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 619–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA [Google Scholar]