Abstract

The kidney is a relatively infrequent site for solitary fibrous tumor (SFT). Among the previously reported cases, only two cases of malignant renal SFT developing via dedifferentiation from a pre-existing benign SFT have been reported. Here we reported a case of de novo malignant renal SFT clinically diagnosed as renal cell carcinoma in a 50-year-old woman. The tumor was circumscribed but unencapsulated and showed obvious hemorrhagic necrosis. Microscopically, the tumor was composed of patternless sheets of alternating hypercellular and hypocellular areas of spindle cells displaying mild to moderate nuclear atypia, frequent mitoses up to 8 per 10 high power fields, and a 20% Ki-67 proliferative index. Immunohistochemical studies revealed reactivity for CD34, CD99 and vimentin, with no staining for all other markers, confirming the diagnosis of SFT. No areas of dedifferentiation were seen after extensive sampling. Based on the pathologic and immunohistochemical features, a diagnosis of de novo malignant renal SFT was warranted. Our report expands the spectrum of malignant progression in renal SFTs. Even though this patient has been disease-free for 30 months, long-term follow-up is still mandatory.

Keywords: solitary fibrous tumor, kidney, malignant, de novo, dedifferentiation, CD34

Backround

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) are distinctive mesenchymal tumors most commonly described as pleural-based lesions; however they can develop at any extrapleural anatomic site [1]. Although the clinical course of SFTs is rather unpredictable, the prognosis of SFTs is generally favorable. It is estimated that 10% to 15% of intrathoracic SFTs and up to 10% of extrathoracic SFTs will recur and/or metastasize [2,3], therefore SFT is regarded as an "intermediate malignant, rarely metastasizing" neoplasm [4]. Microscopic features associated with malignancy in both intrathoracic and extrathoracic SFTs include nuclear atypia, increased cellularity and more than 4 mitoses per 10 high power fields [4,5]. An additional factor conferring a worse prognosis in SFTs is dedifferentiation or sarcomatous overgrowth, which represents an abrupt transition to a morphologically anaplastic component [6]. The kidney is a relatively infrequent site for SFT, with at least 36 cases reported in a review article [7]. The vast majority of renal SFTs are histologically benign and only two cases of malignant renal SFTs developing via dedifferentiation or sarcomatous overgrowth from a pre-existing benign SFT have been reported [7,8]. Here we report the first case of de novo malignant renal SFT without dedifferentiation and thus expand the spectrum of malignant progression in renal SFTs.

Case presentation

Clinical summary

A 50-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with one-month history of soreness and pain in her right flank, without gross hematuria or other constitutional symptoms. Laboratory findings were unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a palpable right flank mass. A computed topography (CT) of the abdomen showed a huge necrotic tumor occupying the perirenal space of right kidney without evidence of either local invasion or lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). The patient underwent right radical nephrectomy under a pre-operative diagnosis of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage II (T2aN0) renal cell carcinoma. Post-operation course was smooth. Neither chemotherapy nor radiation therapy was given. She has been well without evidence of recurrence or metastasis for 30 months.

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen. Arterial phase images of dynamic computed topography scan showed a highly necrotic tumor compressing the renal parenchyma without either invasion to surrounding tissues or local lymphadenopathy.

Pathologic findings

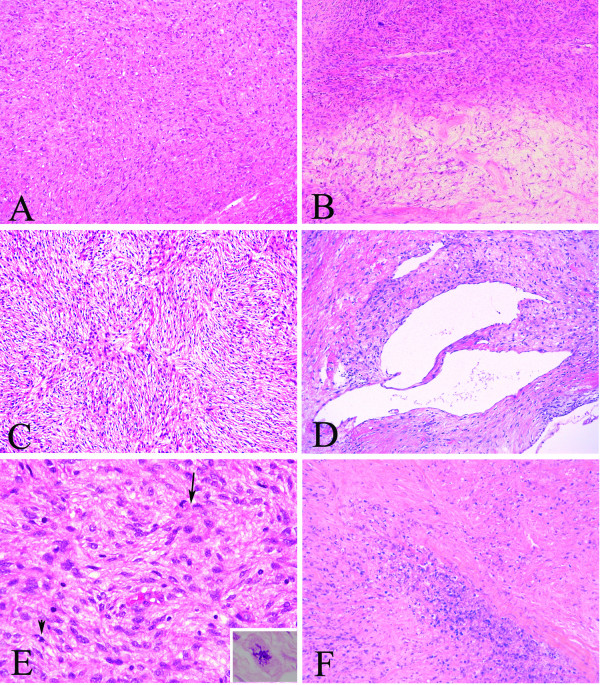

A nephrectomy specimen (15 × 9 × 7 cm, 670 g) with attached ureter and perirenal fibroadipose tissue was received. The specimen was bisected to reveal a 9 × 9 × 6 cm circumscribed but unencapsulated tumor occupying the perirenal space of the upper and middle poles of kidney. The tumor was firm and showed a yellowish white to tan-gray, myxoid and lobulated cut surface with prominent hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 2). Microscopically, the tumor showed proliferation of spindle cells arranging in a patternless architecture (Figure 3A) with a combination of alternating hypercellular and hypocellular areas (Figure 3B). Haphazard, storiform, or short fascicular arrangements of spindle cells in a loose myxoid to fibrous stroma containing dense collagen fibers were also seen (Figure 3C). Dilated and branching hemangiopericytoma-like vessels were frequently observed (Figure 3D). Tumor cells had plump, fusiform, or elongated hyperchromatic nuclei with mild to moderate pleomorphism and indistinct cell borders and frequent mitoses up to 8 per 10 high power fields. Abnormal mitoses were occasionally seen (Figure 3E). Tumor necrosis was evidently present (Figure 3F). We did not find any areas of dedifferentiation after extensive tumor sampling.

Figure 2.

Gross morphology. The tumor was firm and showed a yellowish white to tan-gray, myxoid and lobulated cut surface with prominent hemorrhage and necrosis in the center.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs. A, Proliferation of spindle cells arranging in a patternless architecture (×200 original magnification). B, Alternating hypercellular and hypocellular areas of spindle cells separated from each other by bands of collagen fiber (×200 original magnification). C, Spindle cells forming haphazard, storiform, or short fascicular arrangements in a loose myxoid to fibrous stroma containing dense collagen fibers (×200 original magnification). D, Hemangiopericytoma-like staghorn-like vessels (×200 original magnification). E, Tumor cells displaying mild to moderate atypia and 3 mitoses in this high power field (arrow and arrowhead) (×400 original magnification). Abnormal mitoses were occasionally seen (inset, ×400 original magnification). F, Prominent tumor necrosis (× 400 original magnification).

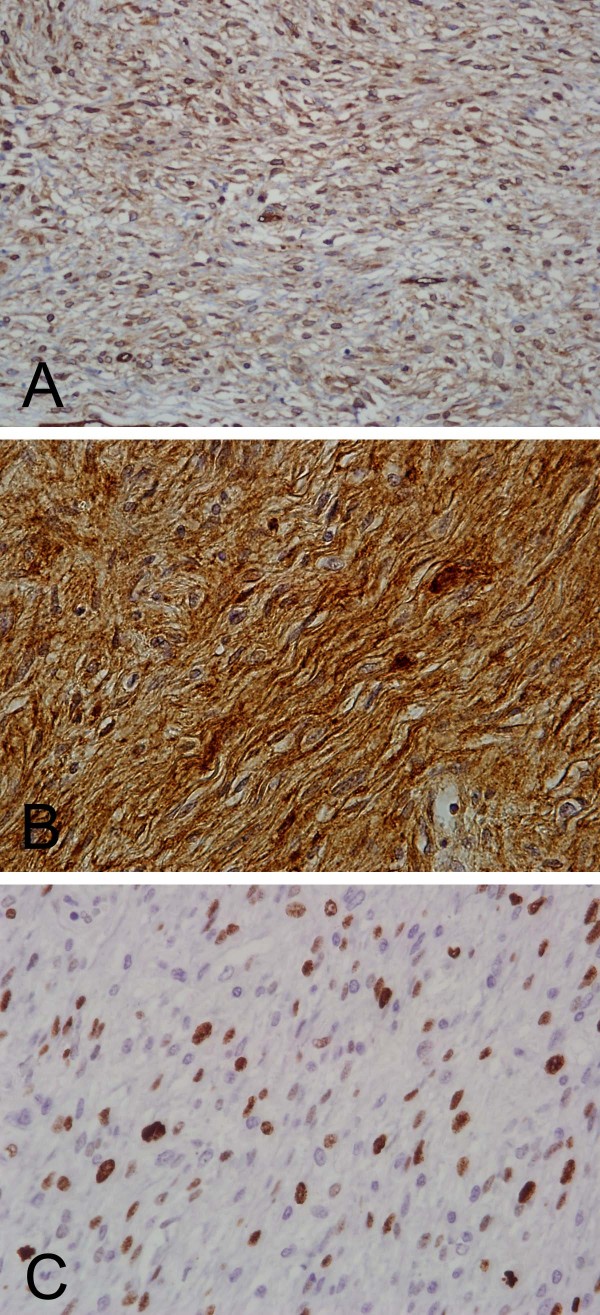

Immunohistochemically, the tumor showed weak CD34 positivity (Figure 4A) and diffusely strong CD99 (Figure 4B) and vimentin staining. They stained negatively for bcl-2 protein, S-100 protein, NSE, muscle markers, cytokeratin, CD117(C-kit), p53 and HMB-45. Ki-67 immunostaining, analyzed by ImmuoRatio quantitative image software [9], showed a 20% proliferative index. The immunohistochemical findings were highly consistent with SFT. Based on the microscopic features including increased cellularity, cellular atypia, frequent mitoses, a high proliferative index, necrosis and absence of dedifferentiation, a diagnosis of de novo malignant solitary fibrous tumor was established.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical photomicrographs. Immunohistochemicaly, the tumor cells showing A, Weak to moderate CD34 immunostaining (×200 original magnification). B, Strong and diffuse CD99 immunostaining (×200 original magnification). C, Ki-67 immunostaining, analyzed by ImmuoRatio quantitative image software, showing a 20% proliferative index (×400 original magnification).

Discussion

SFT is a relatively uncommon but distinctive mesenchymal neoplasm, originally described in the pleura cavity and later reported to occur ubiquitously [1]. Although the histogenesis of SFT remains undetermined, recent studies strongly favor a primitive mesenchymal or perivascular cell origin [10]. The kidney is a relatively infrequent site for SFT, with approximately at least 36 cases of renal SFT reported in a review article [7]. Clinically, these cases were frequently considered to be malignant due to their large tumor size by physical examinations and radiographic studies. Symptoms do not differ from those reported by patients with renal cell carcinoma. Hypoglycemia, which is a rare symptom in intrathoracic and extrathoracic SFTs, was not reported in any renal SFTs including our case [2].

Malignant behaviors in the form of recurrence and/or metastases can occur in 10% to 15% of intrathoracic SFTs and up to 10% of extrathoracic SFTs [2,3]. Malignant SFT is postulated to develop via two pathways: (1) de novo occurrence or (2) dedifferentiation or sarcomatous overgrowth from a pre-exsisting histologically benign SFT [1,4]. Most renal SFTs were classified as histologically benign and showed a favorable prognosis, with no evidence of recurrence during a follow-up period ranging from 2 to 89 months [7]. To our knowledge, two cases of malignant renal SFTs developing via dedifferentiation or sarcomatous overgrowth from a pre-existing benign SFT have been reported by Margo et al. and Fine et al., respecvievely [7,8]. A detailed comparison of the clinicopatholgoic features of these two cases and ours is summarized in Table 1. The tumor reported by Fine et al. had infiltrative borders and focal necrosis, and invaded beyond the renal capsule. The tumor described by Margo et al. was a 9-cm circumscribed mass devoid of either hemorrhage or necrosis. Notably, there was a 3-cm nodular area within the main tumor, microscopically responding to sarcomatous overgrowth. In contrast, our tumor showed a homogeneous cut surface with prominent necrosis and hemorrhage. Microscopically, the tumor reported by Fine et al. and Margo et al. showed typical features of benign SFT with 90% and 30% of dedifferentiation or sarcomatous overgrowth, respectively. In contrast, our tumor appeared to develop de novo since we did not find any areas of dedifferentiation after extensive tumor sampling.

Table 1.

Comparsion of the clinicopathologic features of malignant renal solitary fibrous tumor

| Fine et al. | Margo et al. | Present case | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 76 | 34 | 50 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female |

| Location | Left kidney | Left kidney | Right kidney |

| Size | 12 × 10 × 7.5 cm | 9 cm, with a distinct 3-cm nodule | 9 × 9 × 6 cm |

| Tumor borders | Infiltrative with invasion beyond the renal capsule | Circumscribed | Circumscribed, unencapsulated |

| Necrosis | Focal | Absent | Marked |

| Hemorrhage | NA | Absent | Present |

| Histology | 10% benign SFT 90% dedifferentiation | 70% benign SFT 30% dedifferentiation | De novo malignant SFT |

| Mitoses | Frequent | 2-6/10 HPF | 8/10 HPF |

| Atypia | Marked in areas of dedifferentiation | Marked in areas of dedifferentiation | Mild to moderate |

| Ki-67 proliferative index | NA | 1-4% | 20% |

| CD34 | Loss of expression in areas of dedifferentiation | Positive | Positive |

| Follow-up | Multiple lung nodules 4 month after nephrectomy | 15 months, NED | 30 months, NED |

NA: not available, NED: no evidence of disease

The criteria for clinical malignancy in intrathoracic SFT, first proposed by England et al. in 1989, include increased cellularity, pleomorphism, mitotic count more than 4 per 10 high power fields, necrosis, hemorrhage, size more than 10 cm, non-pedunculated and atypical locations (parietal pleura, pulmonary parenchyma) [5]. The diagnostic criteria for malignant extrathoracic SFTs are purely microscopic and include increased cellularity, pleomorphism and mitotic count more than 4 per 10 high power fields [4,11]. Currently the impact of tumor characteristics (size, hemorrhage, necrosis and location) in predicting clinical malignancy in extrathoracic SFTs remains to be investigated. Our case fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for malignant extrathoracic SFTs. Additionally, the presence of hemorrhage and necrosis and a 20% Ki-67 proliferative index further supports a diagnosis of malignant renal SFT.

SFTs show a wide variety of microscopic growth patterns and should be distinguished from benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Positive immunoreactivity for CD34 and CD99 is characteristic of SFT, and highly valuable in differentiating from other mesenchymal tumors [2,4]. However the expression of CD34 and CD99 may be decreased or absent in areas with marked atypia or dedifferentiation [8,12]. Genetic analyses of SFT to date have not found consistent and characteristic cytogenetic abnormalities that can be used an ancillary diagnostic marker. Missense mutation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFR-β) has been reported in 2 of 88 pleuro-pulmonary SFTs [13], but we did not detect PDGFR-β mutation in our case (data not shown).

The prognosis of extrapleural SFTs is more unpredictable than that of pleural tumors due to lack of large-scale studies. The clinical outcomes were rather strikingly different in the two malignant renal SFTs with dedifferentiation. While a patient developed multiple small lung nodules 4 months post-operatively [8], the other patient was disease-free after 15 months of follow-up [7]. Our patient has been well without evidence of recurrence or metastasis for 30 months. Some studies indicated that extrapleural SFTs had similar prognosis as the pleural counterpart, and a tumor with malignant histological feature was associated with recurrence and metastasis [3,14], but other studies showed that extrapleural SFTs tended to have a favorable outcome than pleural ones, even those with malignant histological features [11,15]. Studies also showed that deep-seated locations, over-expression of p53 and p16, loss of CD34 immunostaining and the presence of dedifferentiated areas may indicate more aggressive behaviors [6]. Complete surgical excision and long-term follow-up are generally recommended for patients with extrapleural SFTs [15]. Besides, due to the rich vascularity and possible origin from pericytes, antiangiogenic therapy, especially for the advanced cases is also under clinical investigation [16].

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. Submission of this case report was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Tao-Yuan, Taiwan. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

List of abbreviations

SFT: solitary fibrous tumor

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TYH was responsible for data collection, literature search and manuscript preparation. YCCC carried out gross and microscopic examinations. WHC performed the surgery and clinical follow-up of the patient. CSC interpreted pre-operative and follow-up imaging studies. CLC, CCH and HPC participated in the microscopic analyses and helped making a final diagnosis. JRC participated in manuscript preparation and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Tsan-Yu Hsieh, Email: b8902059@gmail.com.

Yi-Che ChangChien, Email: ccwilly@hotmail.com.

Wen-Hsiang Chen, Email: c04336@cgmh.org.tw.

Siu-Chung Chen, Email: chan0149@cgmh.org.tw.

Liang-Che Chang, Email: lc2008@cgmh.org.tw.

Cheng-Cheng Hwang, Email: rrooyyaa@cgmh.org.tw.

Hui-Ping Chein, Email: jacqline815@gmail.com.

Jim-Ray Chen, Email: jimrchen@cgmh.org.tw.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate Drs. Jonathan I. Epstein and Elizabeth Montgomery at the Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA for confirming our diagnosis.

References

- Chan JK. Solitary fibrous tumour--everywhere, and a diagnosis in vogue. Histopathology. 1997;31:568–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.2400897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. In: Soft Tissue Tumor. 5. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editor. Philadephia: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Soft tissue tumors of intermediate malignancy of uncertain type; pp. 1093–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Vallat-Decouvelaere AV, Dry SM, Fletcher CD. Atypical and malignant solitary fibrous tumors in extrathoracic locations: evidence of their comparability to intra-thoracic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1501–11. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillou LFJ, Fletcher CDM, Mandahi N. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editor. Lyon: IARCPress; 2002. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumour and hemangiopericytoma; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640–58. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera JM, Fletcher CD. Expanding the spectrum of malignant progression in solitary fibrous tumors: a study of 8 cases with a discrete anaplastic component--is this dedifferentiated SFT? Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1314–21. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a6cd33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro G, Emmanuele C, Lopes M, Vallone G, Greco P. Solitary fibrous tumour of the kidney with sarcomatous overgrowth. Case report and review of the literature. APMIS. 2008;116:1020–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine SW, McCarthy DM, Chan TY, Epstein JI, Argani P. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: report of a case and comprehensive review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:857–61. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-857-MSFTOT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen VJ, Ruotoistenmaki S, Viitanen A, Jumppanen M, Isola J. ImmunoRatio: a publicly available web application for quantitative image analysis of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and Ki-67. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R56. doi: 10.1186/bcr2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide F, Obara K, Mishima K, Saito I, Kusama K. Ultrastructural spectrum of solitary fibrous tumor: a unique perivascular tumor with alternative lines of differentiation. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:646–52. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-1261-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, Hasegawa F, Sano T, Hirohashi S. Extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors: their histological variability and potentially aggressive behavior. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1464–73. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi T, Tsuzuki T, Yatabe Y, Suzuki M, Kurumaya H, Koshikawa T, Kuhara H, Kuroda M, Nakamura N, Nakatani Y. et al. Solitary fibrous tumour: significance of p53 and CD34 immunoreactivity in its malignant transformation. Histopathology. 1998;32:423–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirosi L, Lantuejoul S, Cavazza A, Murer B, Yves Brichon P, Migaldi M, Sartori G, Sgambato A, Rossi G. Pleuro-pulmonary solitary fibrous tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study of 88 cases confirming the prognostic value of de Perrot staging system and p53 expression, and evaluating the role of c-kit, BRAF, PDGFRs (alpha/beta), c-met, and EGFR. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1627–42. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31817a8a89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunnemann RB, Ro JY, Ordonez NG, Mooney J, El-Naggar AK, Ayala AG. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1034–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimitsu Y, Nakajima M, Hisaoka M, Hashimoto H. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: clinicopathologic study of 17 cases and molecular analysis of the p53 pathway. APMIS. 2000;108:617–25. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MS, Araujo DM. New insights into the hemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous tumor spectrum of tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:327–31. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32832c9532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]