Abstract

Hydrogels provide three-dimensional frameworks with tissue-like elasticity and high permeability for culturing therapeutically relevant cells or tissues. While recent research efforts have created diverse macromer chemistry to form hydrogels, the mechanisms of hydrogel polymerization for in situ cell encapsulation remain limited. Hydrogels prepared from chain-growth photopolymerization of poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) are commonly used to encapsulate cells. However, free radical associated cell damage poses significant limitation for this gel platform. More recently, PEG hydrogels formed by thiol-ene photo-click chemistry have been developed for cell encapsulation. While both chain-growth and step-growth photopolymerizations offer spatial-temporal control over polymerization kinetics, step-growth thiol-ene hydorgels offer more diverse and preferential properties. Here, we report the superior properties of step-growth thiol-ene click hydrogels, including cytocompatibility of the reactions, improved hydrogel physical properties, and the ability for 3D culture of pancreatic β-cells. Cells encapsulated in thiol-ene hydrogels formed spherical clusters naturally and were retrieved via rapid chymotrypsin-mediated gel erosion. The recovered cell spheroids released insulin in response to glucose treatment, demonstrating the cytocompatibility of thiol-ene hydrogels and the enzymatic mechanism of cell spheroids recovery. Thiol-ene click reactions provide an attractive means to fabricate PEG hydrogels with superior gel properties for in situ cell encapsulation, as well as to generate and recover 3D cellular structures for regenerative medicine applications.

Keywords: Hydrogel, photopolymerization, type 1 diabetes, degradation

1. Introduction

Hydrogels are a class of hydrophilic, crosslinked polymers that serve as ideal matrices for cell encapsulation and delivery [1, 2], as well as for controlled release of biomacromolecues for tissue regeneration [3, 4]. Many polymers, synthetic or natural, have been utilized to create hydrogels for biomedical applications. For example, derivatives of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) macromers have been widely used due to their tissue-like elasticity, well-defined chemistry, and tunable biochemical, biophysical, and biomechanical properties. Coupling with photopolymerizations as a gelation mechanism, PEG hydrogels can be synthesized with spatial-temporally defined features and properties to control cellular activities, such as spreading, migration, and differentiation [5–7].

PEG diacrylate (PEGDA) hydrogels crosslinked from radical-mediated chain-growth photopolymerizations have been used in numerous drug delivery and cell encapsulation studies [8–16]. The crosslinking density of PEGDA hydrogels can be easily controlled to yield gels with different levels of elasticity and water content, which affect biomolecular transport and cell survival. To obtain high hydrogel mesh size (ξ) for facile biomolecular transport, and thus enhancing cell survival in PEGDA hydrogels, PEG macromers with higher number average molecular weights ( > 10kDa) are usually preferred [11, 17, 18]. The use of higher molecular weight PEGDA, however, often leads to decreased radical propagation rate since high polymers have lower molar concentrations of functional groups (e.g., acrylates) per unit mass. This also results in decreased polymerization efficiency and higher sol fraction at lower polymer contents. Furthermore, free radicals initially generated from the photoinitiators have long half-life in chain-growth polymerizations because radicals can propagate through vinyl groups on PEGDA, causing high cellular damage during in situ cell encapsulation.

Recently, PEG-peptide hydrogels based on step-growth thiol-ene photopolymerizations have been developed to overcome the disadvantages of chain-growth polymerizations while retaining the advantages of photopolymerizations [19]. Multi-arm PEG-norbornene macromers (e.g., 4-arm PEGNB or PEG4NB) are crosslinked by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) cleavable peptides flanked with bis-cysteines via step-growth photopolymerizations [19]. The resulting thiol-ene networks are more homogeneous and have higher functional group conversion when comparing to chain-growth polymerized gels with similar crosslinking density. Thiol-ene photopolymerization is considered a ‘click’ reaction due to the rapid and orthogonal reaction between the ene and thiol functionalities. Furthermore, all advantages offered by photopolymerizations (e.g., spatial-temporal control over reaction kinetics) are retained in thiol-ene hydrogels [19].

Thiol-ene hydrogels have emerged as an attractive class of hydrogels for studying 3D cell biology [20, 21], for controlled release of therapeutically relevant proteins [22], for directing stem cell differentiation [23], and for promoting tissue regeneration [24]. A variety of cell types have been successfully encapsulated in PEG-norbornene hydrogels, including fibroblasts [19, 20], valvular interstitial cells (VICs) [21], mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [23], and fibrosarcoma cells (HT-1080) [20]. In addition, enzyme-sensitive, surface-eroding thiol-ene hydrogels have also been developed for enzyme-responsive protein delivery [22].

One emerging application of photopolymerized PEG hydrogels is the fabrication of bioactive and immuno-isolating barriers for encapsulation of cells, including insulin-secreting pancreatic β-cells [11, 13–15, 25]. Photopolymerizations offer an attractive means for rapid and convenient encapsulation of β-cells, while PEG hydrogels provide a framework from which to conjugate diverse functionalities for promoting or suppressing specific cell functions. Despite tremendous efforts toward creating permissive and promoting microenvironments for β-cells, challenges remain and the field of β-cell delivery may benefit from a highly cytocompatible gel system that causes minimum, if any, cellular damage during in situ cell encapsulation. The major hurdle to the success of photopolymerized PEG hydrogels in β-cells encapsulation is the necessary use of photoinitiator, which, upon light exposure, generates free radicals that may cause stresses and cellular damage during the encapsulation processes [11].

In this contribution, we report the superior cytocompatibility of step-growth thiol-ene click reactions and hydrogels for pancreatic β-cells (MIN6). Using chain-growth photopolymerized PEGDA hydrogels as controls, we studied the cytocompatiblity of the thiol-ene reactions, as well as the physical properties of the resulting hydrogels. We further developed a thiol-ene hydrogel system composed of a PEG4NB macromer and a simple bis-cysteine-terminated and chymotrypsin-sensitive peptide sequence (CGGY↓C, arrow indicates enzyme cleavage site) for the encapsulation of MIN6 β-cells. The survival, proliferation, and formation of β-cells spheroids in this thiol-ene hydrogel system were systematically studied. Finally, we characterized the erosion of this unique chymotrypsin-sensitive gel system and utilized it for the rapid recovery of viable and functional 3D β-cell spheroids formed naturally in these thiol-ene hydrogels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

4-arm PEG (20kDa) and PEG monoacrylate (PEGMA, 4kDa) were obtained from JenKem Technology USA and Monomer-Polymer Dajac & Labs, respectively. Fmoc-amino acids were purchased from Anaspec. CellTiter Glo® and Alamarblue® reagents were obtained from Promega and AbD Serotec, respectively. Trypsin-free α-chymotrypsin was obtained from Worthington Biochemical Corp. Live/Dead cell viability kit for mammalian cells was purchased from Invitrogen. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless noted otherwise.

2.2 PEG4NB, PEGDA, and photoinitiator lithium arylphosphanate (LAP) synthesis

4-arm PEG-norbornene (PEG4NB) was synthesized according to an established protocol [19] with slight modification. Briefly, N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC, 2.5X) was reacted with norbornene acid (10X) in dichloromethane (DCM) to form an intermediate product - norbornene carboxylic acid O-acyl-urea, followed by the formation of norbornene anhydride and by-product dicycolhexylurea. Norbornene anhydride was filtered through a fritted funnel and added into a second flask containing pre-dissolved 4-arm PEG-OH, 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, 0.5X), and pyridine (5X) in DCM. All reactions were performed under nitrogen. The flask was placed in an ice bath and the reaction was allowed to proceed overnight. The product was filtered and redissolved in DCM and then precipitated in cold ethyl ether. The precipitated product was extracted with ether in an Allihn condenser extractor system at 50°C for 48hr, followed by drying in a desiccator. The degree of functionalization (>90%) was characterized by proton NMR.

The synthesis of PEGDA [12, 26] and photoinitiator lithium arylphosphanate (LAP) [27] were performed according to published protocols.

2.3 Peptide synthesis

All peptides were synthesized using standard solid phase peptide synthesis in a microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM Discover SPS). Briefly, Fmoc-Rink-amide-MBHA resin was swell in dimethylformamide (DMF) for 15min. The deprotection procedures (in 20% piperidine/DMF with 0.1M HOBt) were performed in the peptide synthesizer for 3 min at 75°C with microwave power set at 20W. Fmoc-protected amino acids (5-fold molar excess) were dissolved in an activator solution (0.28M DIEA in DMF) containing HBTU (5-fold molar excess). The activated Fmoc-amino acid solution was added to the deprotected resin and the coupling reactions were performed in the synthesizer for 5 min at 75°C and 20W. The coupling of Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH was performed at 50°C to decrease the racimification reaction. Ninhydrin test was conducted after each coupling and deprotection step to ensure completion of each step. In rare cases, amino acid coupling reactions were repeated until a negative Ninhydrin test result was obtained. The synthesized peptides were cleaved in 5mL cleavage cocktail (95% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 2.5% triisopropylsilane (TIPS), 2.5% distilled water, and 250mg of phenol) in the synthesizer for 30min at 38°C and 20W. Cleaved peptides were precipitated in cold ether, dried in vacuuo, lyophilized, and stored in −20°C. The concentrations of the sulfhydryl group on the cysteine-containing peptides were quantified using Ellman’s reagent (PIERCE).

2.4 Non-gelling photopolymerizations and cell viability assay

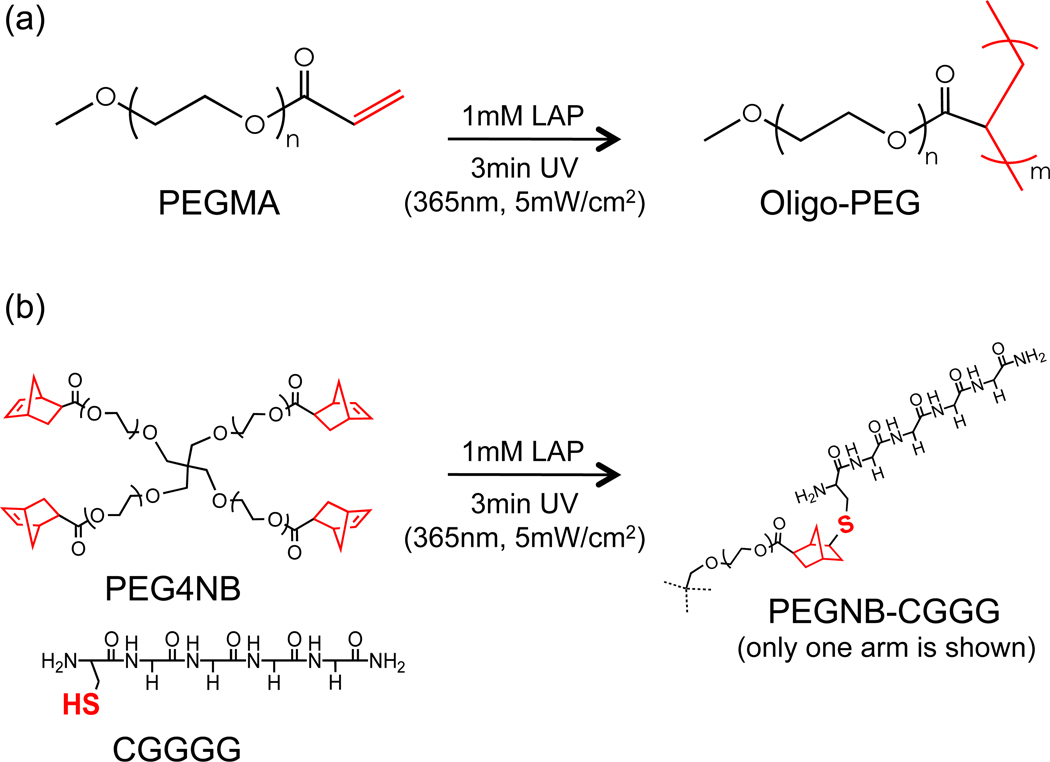

MIN6 β-cells at desired densities were suspended in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing required macromolecular components. For non-gelling chain-growth photopolymerizations (Scheme 1a), PEGMA (4kDa) at 16mM was used. For non-gelling step-growth thiol-ene photopolymerizations (Scheme 1b), 8mM PEG4NB (20kDa) and 8mM mono-cysteine peptide CGGGG were combined to yield a total functionality of 16mM. Photoinitiator LAP was added at 1mM (0.028wt%) when needed. Half of the pre-polymer solutions containing cells were exposed to UV (365nm, 5mW/cm2) for 3min (identical to that used in cell encapsulation). Following photopolymerizations, 5µL of cell solutions (with or without UV exposure) were combined with 50µL of HBSS and 50µL of Celltiter Glo® reagent for quantification of intracellular ATP concentrations using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments). Standard curves using known concentrations of ATP monohydrate were generated for interpolation of unknown ATP concentrations.

Scheme 1.

Schematics of non-gelling photopolymerizations: (a) Chain-growth photopolymerization of PEGMA into Oligo-PEG. (b) Step-growth thiol-ene click reaction using PEG4NB and mono-cysteine peptide (CGGGG) to form non-crosslinked PEG-peptide conjugates. Photoinitiator: 1mM LAP (lithium arylphosphanate).

2.5 Dynamic viscometry

Viscosity of the macromer solutions with or without UV exposure was measured on a Bohlin CVO 100 digital rheometer (Viscometry mode, 4° cone/plate geometry, gap = 150µm). Dynamic viscosity measurements were conducted at 25°C and in controlled shear rate (100 to 400 s−1).

2.6 Hydrogel fabrication and characterization

Chain-growth PEG hydrogels were photopolymerized from desired concentrations of PEGDA (10kDa) and in the presence of 1mM LAP (3min UV at 365nm, 5mW/cm2). Step-growth thiol-ene hydrogels were formed from PEG4NB (20kDa) and a chymotrypsin-sensitive peptide crosslinker (CGGYC). Gels were formed in 1mL syringes with open tips for gel removal. To characterize gel fraction, all components were dissolved in double distilled water (ddH2O), and gels (60µL) were dried in vacuo immediately following photopolymerization. The dried weights obtained gravimetrically contain both crosslinked (gel fraction) and uncrosslinked (sol fraction) polymers. The gels were then incubated in ddH2O on an orbital shaker for 24hr for removing sol fraction. Gels were dried again to obtain crosslinked polymer weight, from which to calculate the gel fractions (ratios between the two dried weights). For equilibrium gel swelling, polymerized hydrogels were placed in ddH2O for 24hr to allow diffusion of unreacted macromers, followed by drying in vacuo to obtain dried gel weight (Wdried). The dried gels were then placed in PBS for 48hr. The swollen weights of the gels (Wswollen) were obtained gravimetrically for determining swelling ratios based on the following equation: Q = Wswollen/Wdried.

The obtained swelling ratios were used to calculate hydrogel mesh sizes as described elsewhere [3, 26, 28].

2.7 Rheometry

In situ gelation and rheometry studies were conducted on a Bohlin CVO 100 digital rheometer equipped with a UV curing cell (parallel plate geometry). Prepolymer solutions were irradiated with an Omnicure S1000 spot curing system (365nm, 5mW/cm2) through a liquid light guide. The gap was set at 100µm. Oscillatory rheometry was performed with 10% strain and at a frequency of 1Hz. Strain sweep was performed after gelation to ensure the operation was in the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). Gel point (or crossover point) was defined as the time when storage modulus (G’) surpasses loss modulus (G”).

Shear moduli of the gels were measured right after gelation or after incubating gels in PBS for 48hr. Gel samples (8mm diameter × 1mm thickness) were loaded between parallel plates and strain sweep was performed at a frequency of 1Hz and under 0.1N normal force. Frequency sweep was performed to ensure the operation was within LVR.

2.8 Cell encapsulation & viability assays

Cells at desired densities were suspended in polymer solutions and exposed to identical UV conditions as described earlier. MIN6 cell-laden hydrogels (25µL) were maintained in high glucose DMEM (HyClone) containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 1x Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Invitrogen, 100u/mL penicillin, 10µg/mL streptomycin, and 250ng/mL Fungizone), and 50µM β-mercaptoethanol. To determine long-term cell viability in hydrogels, cell-laden hydrogels were incubated in 500µL Alamarblue® reagent (10% in cell culture medium) for 16hr. Following incubation, 200µL media were transferred to a black 96-well plate and fluorescence (excitation: 560nm, emission: 590nm) generated due to non-specific cell metabolic activity was determined in a microplate reader.

2.9 Chymotrypsin-mediated gel erosion and recovery of cell spheroids

PEG4NB-CGGYC hydrogels (4wt%, 25µL) were prepared as described earlier. The gels were incubated in PBS for 48hr prior to gel erosion assay. Trypsin-free α-chymotrypsin was dissolved in serum-free DMEM at desired concentrations. PEG4NB-CGGYC gels were incubated in 500µL chymotrypsin solution at room temperature for a pre-determined period of time. Gel mass prior to and after chymotrypsin treatment was measured gravimetrically to determine mass loss as a function of time.

For recovery of cell spheroids, cell-laden hydrogels were incubated in serum-free media containing 1mg/mL (40 µM or 63 U/mL) chymotrypsin at room temperature with gentle shaking. Complete gel erosion was achieved within 5 minutes of incubation. Recovered cell spheroids for glucose stimulated insulin release (GSIR) were separated from dissolved polymers by gentle centrifuge (300rpm for 2min) and washed with HBSS once. For GSIR, all cell spheroids were primed in Kerbs Ringer Buffer containing 2mM glucose for 1 hour. After which the spheroids were split in half and incubated in HBSS containing 2mM or 25mM glucose for another 1 hour. Insulin contents were quantified using a mouse insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia). The intracellular ATP concentrations of the recovered spheroids was quantified by CellTiter Glo® reagent and used to normalize the quantified insulin contents.

2.10 Image analysis

Phase contrast images and movies of cell recovery were obtained on a Nikon Ti-U inverted microscope. The diameters of the recovered cell spheroids were measured using Nikon Element software. Confocal images were obtained on an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 Laser Scanning Biological Microscope (IUPUI Nanoscale Imaging Center). To determine cell viability following encapsulation, samples were stained with Live/Dead staining kit immediately following encapsulation. For every experimental condition, confocal images from three samples and at least four random fields (100µm thick, 10µm per slice) within each sample were acquired. A total of 12 confocal z-stack images were used for counting the live (staining green) and dead cells (staining red) in every experimental condition.

2.11 Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test on Prism software. Statistical significance was assigned for 95% confidence. All experiments were conducted independently for three times and results were reported as mean ± SEM.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1 Effect of photocrosslinking conditions on MIN6 β-cell survival

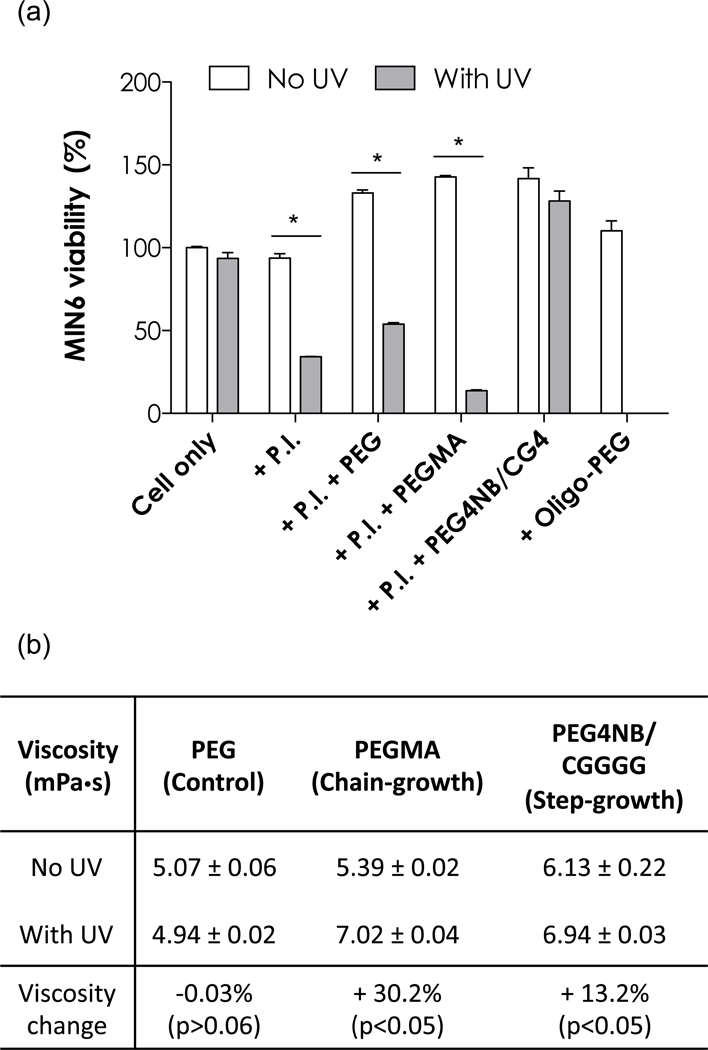

The survival of MIN6 β-cells after photopolymerization process was first studied using non-gelling photopolymerizations (Scheme 1). Following non-gelling photopolymerizations, pre-polymer solutions containing cells, photoinitiator, and PEG macromer remained soluble, thus allowing facile and precise quantification of cell viability. In chain-growth photopolymerizations, PEG-monoacrylate (PEGMA) was polymerized into non-crosslinked and soluble oligo-PEG (Scheme 1a). On the other hand, the non-gelling step-growth thiol-ene click reaction between PEG4NB macromer and mono-cysteine peptides (e.g., CGGGG or CG4) formed soluble 4-arm PEG-peptide conjugates (Scheme 1b). As shown in Figure 1a, exposing MIN6 β-cells (2×106 cells/mL) under long wavelength (365 nm), low intensity (5 mW/cm2) UV for short period of time (3 min) did not affect their survival as determined by intracellular ATP quantification (Cell only group). Exposing MIN6 β-cells under UV in the presence of photoinitiator (1mM LAP), however, resulted in significant cell damage (64% ATP reduction, +P.I. group). The addition of PEGMA (16mM) further exacerbates cellular damage, as shown by a 91% reduction in intracellular ATP concentration (+P.I. +PEGMA group). Pancreatic β-cells are known to undergo apoptosis when exposing to radical species [29–31]. During chain-growth photopolymerizations, the propagating radicals through vinyl groups on PEGMA (or PEGDA) were likely the main reason causing this cellular damage since control experiments using hydroxyl-terminated PEG revealed similar cell damage compared to using LAP alone (~60% ATP reduction, +P.I. +PEG group). In addition, when pre-polymerized oligo-PEG was added to the pre-polymer solutions (without UV exposure), cell survival was not affected (+oligo-PEG group). While chain-growth photopolymerizations caused substantial cell damage, step-growth thiol-ene reactions appear to be highly cytocompatible. Figure 1a shows that, when PEG4NB and CG4 peptide were reacted under the same photoinitiation conditions (+P.I. +PEG4NB/CG4 group), the difference between MIN6 β-cell survival with or without UV exposure had no statistical significance.

Figure 1.

(a) Effect of non-gelling photopolymerizations on MIN6 β-cell survival. P.I.: 1mM photoinitiator (LAP). PEG: 16mM hydroxyl-terminated PEG (4kDa). PEGMA: 16mM PEG monoacrylate (4kDa). PEG4NB/CG4: 8mM PEG4NB and 8mM CGGGG. UV exposure conditions: 365nm, 5mW/cm2, 3min. Cell viability (cellular ATP quantification) without UV exposure was set at 100%. Asterisks represent p<0.05 between indicated groups, (b) Viscosity of macromer solutions before or after UV exposure. Conditions of UV exposure and concentrations of PEGMA and PEG4NB/CG4 were identical to that shown above (N=3, mean ± SEM).

An important consideration in this experiment is that the evolving polymer chains caused changes in solution viscosity, which affects radical diffusion and hence cell viability. To elucidate this possibility, we conducted controlled shear rate viscometry to measure the dynamic viscosity of the macromer solutions before and after non-gelling photopolymerizations for both chain-growth (PEGMA) and step-growth (PEG4NB/CG4) systems. As shown in Figure 1b, the viscosity of non-gelling, chain-growth polymerized oligoPEG (from 16mM PEGMA-4kDa) increased from 5.39 to 7.02 mPa·s (+30.2%) while the viscosity of step-growth PEGNB-CGGGG conjugates (16mM total functionalities) increased from 6.13 to 6.94 mPa·s (+13.2%) after UV exposure. The small viscosity increase in the non-gelling step-growth reaction was as expected because only 4 small peptides (total molecular weight: ~1.4kDa) were conjugated onto one PEG4NB macromer (20kDa), while multiple PEGMA macromers could join together to form a linear oligoPEG with much higher molecular weights. It is reasonable to suggest that increasing solution viscosity decreases radical diffusivity. The correlation between radical diffusivity and cell viability, however, is not straightforward. It is possible that higher radical diffusivity causes more cell damage due to higher radical mobility. On the other hand, one may argue that lower radical diffusivity causes more cell damage due to localized radical activity. While results in Figure 1b implies that reduced radical diffusivity (due to increased viscosity) in chain-growth polymerization caused more cellular damage (as observed in Figure 1a), it cannot explain why cells encapsulated in step-growth thiol-ene hydrogels have higher viability (see sections below) because the gelation time of step-growth thiol-ene hydrogels was much faster (see sections below), causing the solution viscosity to build up more rapidly than chain-growth polymerization. Additional experiments are required to elucidate the exact mechanism but it is out of the scope of the current study. Nonetheless, this encouraging result implies that step-growth thiol-ene photopolymerizations may be a better method for cell encapsulation, even for cells that are sensitive to radical species (e.g., β-cell). Noted that the concentration of ATP was slightly higher in the presence of PEG macromer, presumably due to the macromolecular crowding effect of PEG [32] that increases local cell density (which leads to increased ATP concentration).

3.2 Effect of cell density on photopolymerization induced MIN6 β-cell damage

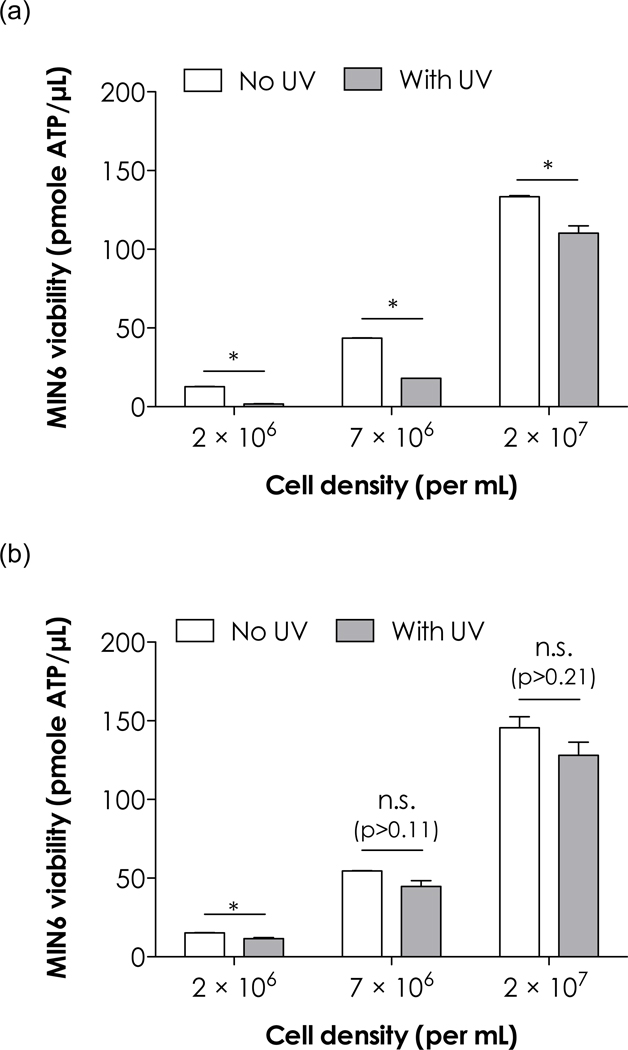

Our previous results showed that increasing β-cell packing density drastically improved their survival in chain-growth PEGDA hydrogel [13]. In this study, we further examined the effect of cell density on photopolymerization induced MIN6 β-cell damage. Figure 2 shows the effect of cell density on the survival of MIN6 β-cells before and after non-gelling chain-growth (Figure 2a) or step-growth (Figure 2b) photopolymerizations. In Figure 2a, it can be seen that while MIN6 β-cells at low density (2×106 cells/mL) did not survive the non-gelling photopolymerization processes, cells at higher densities had higher viability. These results were consistent with our previous finding (i.e. increasing cell density increases cell survival in hydrogels) and the protection effects may be attributed to enhanced cell-cell communication at higher cell density. It is also possible that the degree of cell damage was linked to the concentration of radical species generated during polymerization reactions. More cells survived at higher cell density since limited amount of radical species can only damage a fixed number of cells. Nonetheless, increasing cell density/number has a direct effect of enhancing cell survival in chain-growth photopolymerizations.

Figure 2.

Effect of photopolymerizations on MIN6 β-cell survival at various cell densities, (a) Non-gelling chain-growth photopolymerization of 16mM PEGMA. (b) Non-gelling step-growth thiol-ene reaction using 8mM PEG4NB and 8mM CGGGG (total functionality: 16mM). Both with 1mM LAP, with or without 3min, 365nm, 5mW/cm2 UV exposure. Asterisks represent p<0.05 between indicated groups.

Compared to chain-growth photopolymerizations that largely damaged cell viability, step-growth thiol-ene reactions caused very limited cell damage, even at low cell density (Figure 2b). At a total functionality of 16mM (equal molar concentration of ene and thiol, equivalent to 4wt% PEG4NB), only a small percentage of cells were damaged after UV exposure (23% reduction in ATP). This represents a significant improvement over chain-growth photopolymerization (91% reduction in ATP). While chain-growth polymerizations still caused significant degree of cell damage at higher cell densities (59% and 17% reduction in ATP for 7×106 and 2×107 cells/mL, respectively), no statistical significance on cell survival was found in step-growth reactions at these higher cell densities. In chain-growth photopolymerizations, the percentage of ATP reduction decreases as increasing cell density. This result is consistent with our earlier observation in MIN6 β-cell encapsulation [13]. Noted that the concentration of photoinitiator was kept constant at 1mM, thus the vast difference in β-cell survival was likely due to the nature of chain-growth versus step-growth polymerizations. In chain-growth polymerizations, free radicals propagate through unsaturated vinyl bonds on PEGDA macromers, causing cytotoxic radicals to remain active for a prolonged period. It is also possible that sulfhydryl radicals generated from the thiol groups in thiol-ene photopolymerizaitons are less cytotoxic than carbon radicals in chain-growth photopolymerizations.

3.3 Biophysical properties of PEG hydrogels formed from chain-growth or step-growth photopolymerizations

The non-gelling photopolymerization results revealed that, compared to chain-growth photopolymerization, step-growth photopolymerization is a more cytocompatible reaction for β-cells. Prior to conducting cell encapsulation studies, it is necessary to examine and compare the biophysical properties of PEG hydrogels formed from chain-growth and step-growth photopolymerizations. To obtain this information, we synthesized PEGDA and PEG4NB hydrogels at three macromer concentrations (Table 1). These macromer concentrations were selected based on the PEGDA concentrations (8 to 12 wt%) commonly used in cell encapsulation studies.

Table 1.

Major hydrogel composition used in this study.

- [acrylate] for PEGDA (10kDa)

- [norbornene] + [thiol] for PEG4NB (20kDa)

CGGYC as peptide crosslinker, [thiol] = [norbornene].

We first examined the shear moduli of chain-growth PEGDA and step-growth PEG4NB photopolymerized gels at two conditions: (1) immediately following gelation, and (2) after swelling in PBS at 37°C for 48 hours (Table 2). While increasing macromer functionality from 16mM to 24mM in both systems increased hydrogel moduli, we found that PEG4NB gels had higher shear moduli, compared to PEGDA hydrogels at the same functionality. Another benefit of thiol-ene reactions is their high crosslinking efficiency. Table 3 shows that PEG4NB hydrogels crosslinked by CGGYC (a chymotrypsin sensitive peptide) had higher gel fractions compared to PEGDA hydrogels formed by chain-growth photopolymerizations. For example, at 16mM, PEG4NB-CGGYC gels had a gel fraction of 92%, while the gel fraction of PEGDA gels was only about 63%. The lower gel fraction of PEGDA hydrogels can be used to explain, at least in part, their lower moduli compared to PEG4NB gels with equivalent macromer functionality. Furthermore, it is known that chain-growth polymerized gels have lower mechanical properties compared to step-growth polymerized gels at similar crosslinking density [19]. For in situ gelation, high gel fraction is very important as residual monomers (i.e., sol fraction) may cause unfavorable inflammatory response in vivo.

Table 2.

Elastic moduli of PEGDA and PEG4NB hydrogels (post-synthesis or swollen) with different crosslinking densities. (N=3, Mean ± SEM)

| Total functionality (mM) |

PEGDA, G’ (Pa) |

PEG4NB, G’ (Pa) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-synthesis | Swollen | Post-synthesis | Swollen | |

| 16 | 380 ±15 | 230 ± 40 | 1860 ± 90 | 1390 ± 20 |

| 20 | 1180 ± 60 | 640 ± 30 | 3000 ± 80 | 1860 ± 40 |

| 24 | 2910 ± 80 | 1620 ± 55 | 4260 ± 150 | 2560 ± 130 |

Table 3.

Comparison of hydrogel physical properties. (N=3, mean ± SEM)

| Total Functionality (mM) |

Gel fraction |

Gel point (sec) |

Mesh size (nm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG4NB | PEGDA | PEG4NB | PEGDA | PEG4NB | PEGDA | |

| 16 | 92.0 ± 3.0 | 62.7 ± 2.0 | 7 ± 2 | 125 ± 7 | 22 ± 0.2 | 16 ± 0.5 |

| 20 | 93.4 ± 1.3 | 77.7 ± 1.2 | 6 ± 1 | 101 ± 2 | 21 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 0.1 |

| 24 | 94.7 ± 2.4 | 83.7 ± 1.7 | 3 ± 1 | 65 ± 2 | 20 ± 0.3 | 13 ± 0.1 |

We next examined the gelation kinetics of PEG hydrogels formed from PEGDA or PEG4NB crosslinked by CGGYC. As shown in Table 3, 16mM PEG4NB-CGGYC gels (4wt% PEG4NB with equal thiol and ene concentrations) reached gel point in 7 seconds, while PEGDA gels required 125 seconds at equivalent macromer functionality. For both types of gels, gel point decreases (i.e., faster gelation) at higher macromer concentrations as expected. The gel point for 24mM PEGDA gels (~65 seconds), however, was 22-fold slower than that of PEG4NB gels (~3 seconds) at equal functionality. Noted that the fast gelation of radical-mediated, crosslinked step-growth thiol-ene hydrogels is a result of rapid consumption of monomer species (4-arm PEGNB and bis-cysteine-peptides) early in the polymerization process (thus forming crosslinked network rapidly) and should not be confused with the slow formation of linear polymers using conventional step-growth mechanism. The faster gelation kinetics is beneficial for photoencapsulation of cells, as it decreases UV and free radical exposure to the cells.

Table 3 also shows the mesh size of PEG hydrogels calculated from mass swelling ratios according to the Flory-Rehner theory [3, 26, 28]. Even though step-growth PEG4NB hydrogels had higher gel moduli (Table 2), their estimated mesh sizes were higher than PEGDA hydrogels at equivalent functionality. This result was due to the use of the Flory-Rehner theory, which is commonly used for estimating hydrogel mesh size and assumes that the crosslinking junctions occupy zero volume. It also does not account for network non-ideality. Both of these characteristics are important in interpreting the results reported in Table 2. PEGDA (or PEG-dimethacrylate) hydrogels are known to produce dense hydrophobic poly(meth)acrylate kinetic chains that occupy space and possess significant network non-ideality [33].

3.4 Effect of hydrogel chemistry on survival of encapsulated MIN6 β-cell

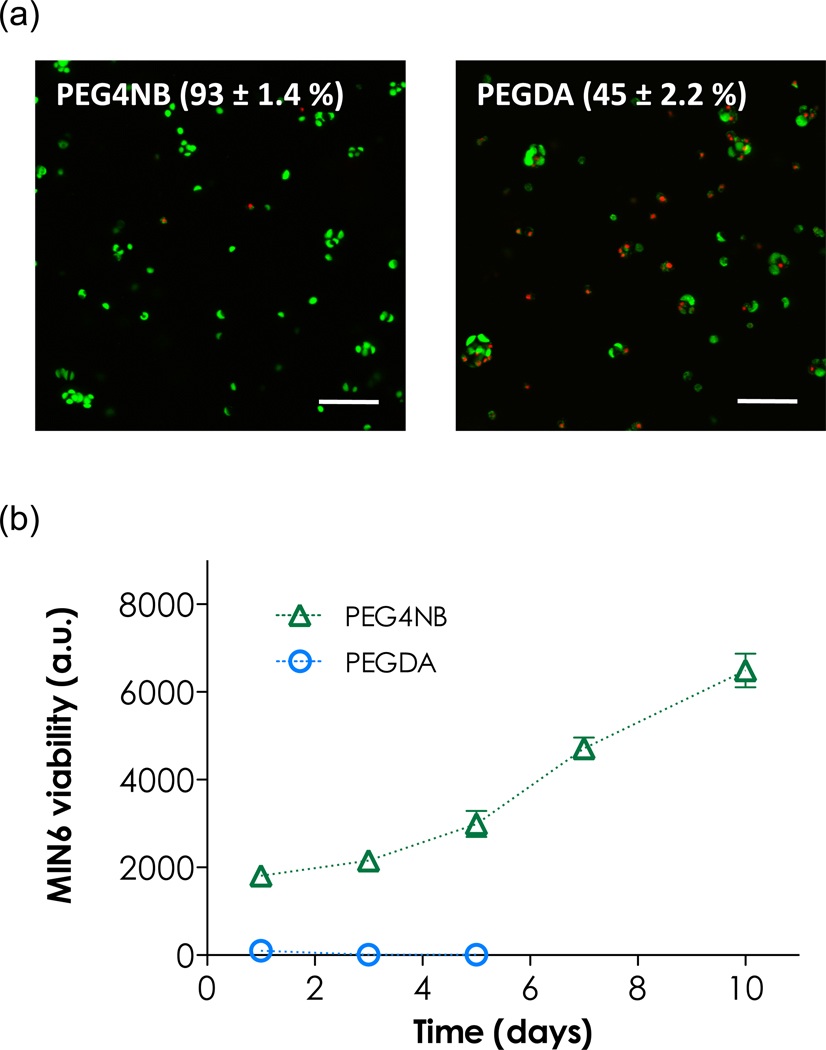

Previous efforts on MIN6 β-cells survival in hydrogels have revealed low cell viability when ECM molecules (e.g., laminin, collagen), cell adhesive ligands (e.g., RGD, IKVAV) or bioactive peptides (e.g., GLP-1) were not incorporated in hydrogels [11, 17]. After obtaining high β-cells viability in the non-gelling thiol-ene reactions (Figure 2b), we were interested in the cell viability in PEG4NB hydrogels. Figure 3a shows the comparison of β-cell survival in PEG4NB/CGGYC or PEGDA hydrogels (encapsulated at 2×106 cells/mL). Cell-laden hydrogels were stained with live/dead assay kit immediately following photoencapsulation and imaged with confocal microscope. Clearly, the viability of MIN6 β-cells in PEG4NB hydrogels was significantly higher than that in PEGDA hydrogels (live cell counts: 93±1.4 % vs. 45±2.2 %). This result was not surprising since the gelation time for step-growth photopolymerizations was much faster than chain-growth photopolymerizations (Table 3), thus limiting the cellular damage caused by the radical species. More importantly, when cells in these two gel systems were cultured for extended period of time, cells in PEG4NB hydrogels eventually survived and proliferated, while cells in PEGDA hydrogels died off rapidly (Figure 3b). This study demonstrated that PEG4NB hydrogels offer a superior microenvironment for cell survival in 3D.

Figure 3.

Viability of encapsulated MIN6 β-cells. (a) Representative confocal z-stack images of MIN6 β-cells encapsulated in PEGDA or PEG4NB gels. Live/dead staining was performed immediately following photo-encapsulation. Cell viability was defined as the percentage of live (green) cells over total cell (green + red) count (370 in PEGDA and 707 in PEG4NB hydrogels). (b) Encapsulated MIN6 β-cell viability as a function of time determined by Alamarblue reagent. (N=3, mean ± SEM)

3.5 Effect of cell packing density on MIN6 β-cell survival and proliferation in thiol-ene hydrogels

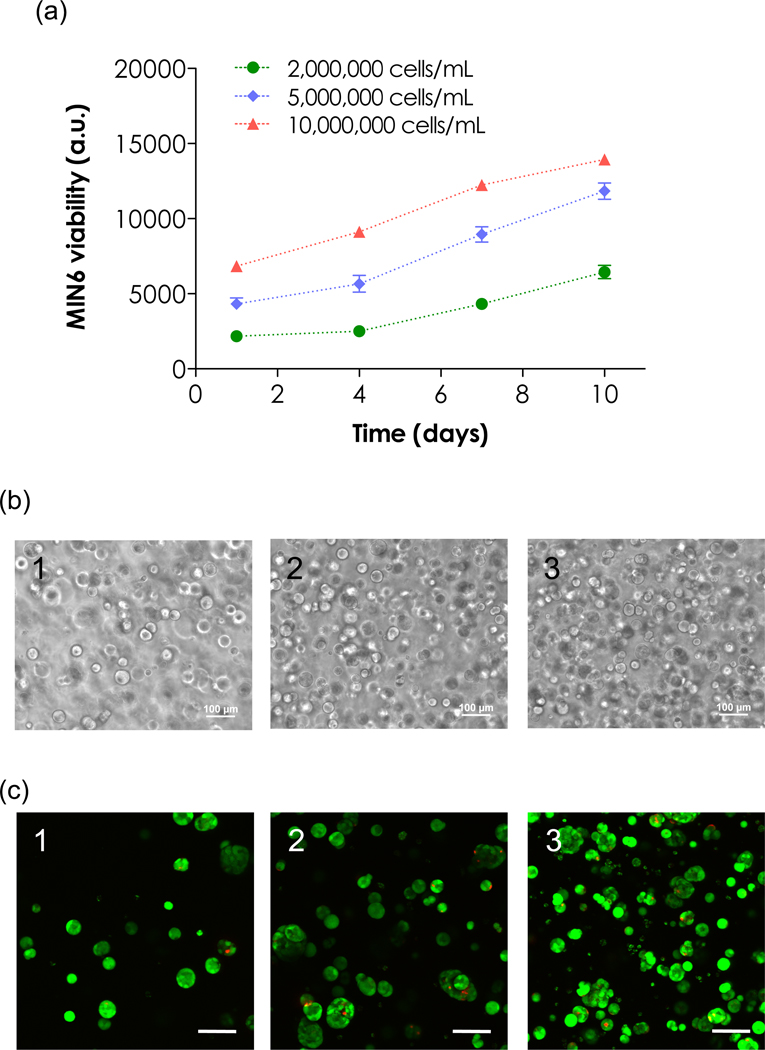

Our previous work has revealed that cell packing density in chain-growth PEGDA hydrogels play a significant role in β-cell survival and function (β-cells at densities below 107 cells/mL did not survive) [13]. Here, we examined this parameter in thiol-ene hydrogels. As shown in Figure 4a, MIN6 β-cells survived and proliferated without any cell-adhesive ligand in PEG4NB hydrogels crosslinked with CGGYC at all three cell packing densities studied. Figure 4b (phase contrast images) and Figure 4c (confocal z-stack images) show the formation of cell spheroids within 10 days. One interesting phenomenon in this study was that although MIN6 β-cells survived and proliferated at low packing density (2×106 cells/mL), these cells did not show significant proliferation in the first 4 days (Figure 4a). This could be explained by the fact that some cells formed loose clusters in hydrogels after photoencapsulation (Figure 3a). While dispersed cells died off without cell-ECM or cell-cell interactions, cells in these loose clusters eventually survived and formed spheroids due to enhanced cell-cell communication.

Figure 4.

Effect of cell packing density on survival of MIN6 β-cells in 4wt% PEG4NB/CGGYC hydrogels. (a) Metabolic activity of MIN6 β-cells in hydrogels determined by Alamarblue reagent (N=3, mean ± SEM). (b) Representative phase contrast images of cell spheroids after in vitro culture for 10 days, (c) Representative confocal z-stack images of cell spheroids stained with live/dead staining kit after in vitro culture for 10 days. (1 = 2×106; 2 = 5×106; 3 = 1×107 cells/mL Scale: 100µm)

3.6 Chymotrypsin-mediated gel erosion

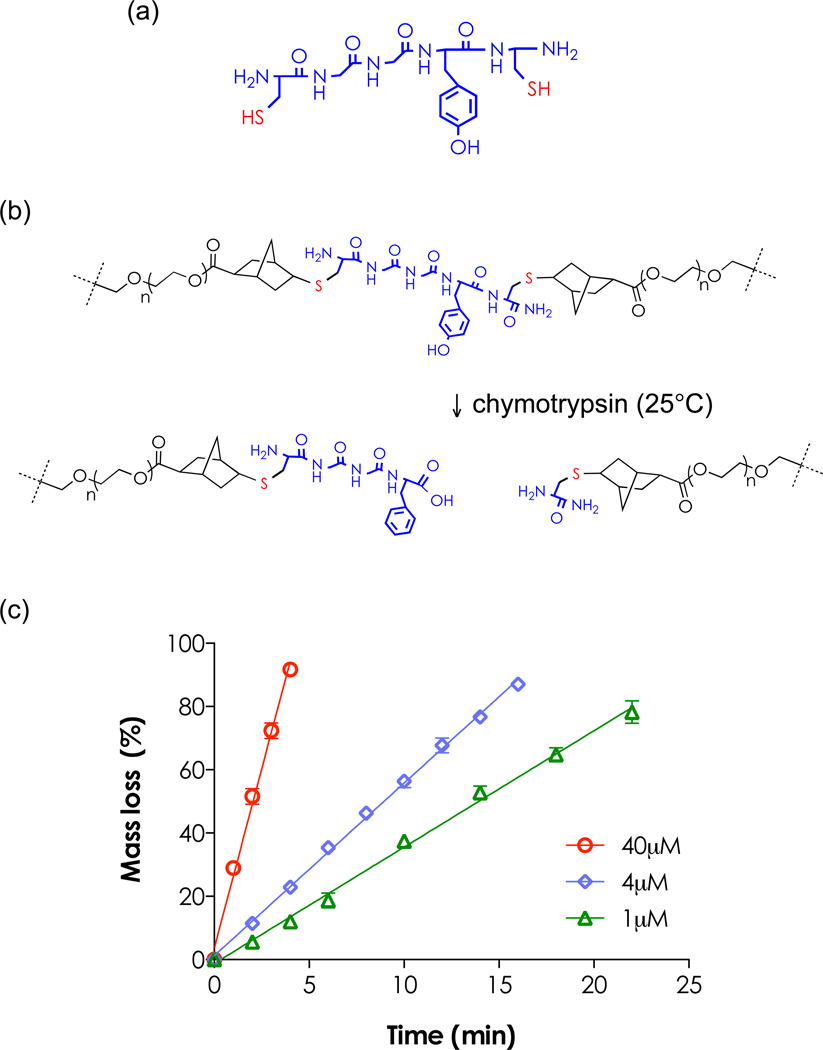

One important feature of thiol-ene hydrogels is that the peptide crosslinkers can be designed to undergo enzymatic degradation, which leads to controlled gel erosion [19, 22]. Figure 5 illustrates the chemical structure of a simple chymotrypsin-sensitive peptide sequence (CGGY↓C) flanked with terminal cysteine for hydrogel crosslinking. Chymotrypsin cleaves amino acid residues with an aromatic ring such as tyrosin (Y), proline (P), and tryptophan (W) [34–36]. When PEGNB/CGGYC gels were incubated in serum-free DMEM containing 40µm (63U/mL) chymotrypsin, gels eroded completely within 5 minute at room temperature with gentle shaking. The linear regression results revealed constant gel erosion rates as time (R2= 0.99 for all three chymotrypsin concentrations tested), indicating that the degradation follows a surface erosion mechanism [22]. This result could be contributed to homogeneous thiol-ene networks and fast enzyme kinetics of chymotrypsin.

Figure 5.

Chymotrypsin-mediated rapid gel erosion, (a) Chemical structure of CGGYC. (b) Schematic of PEG4NB-CGGYC gel erosion, (c) Effect of chymotrypsin concentration on mass loss of PEG4NB-CGGYC hydrogel (4wt% PEG4NB, N=3, mean ± SEM).

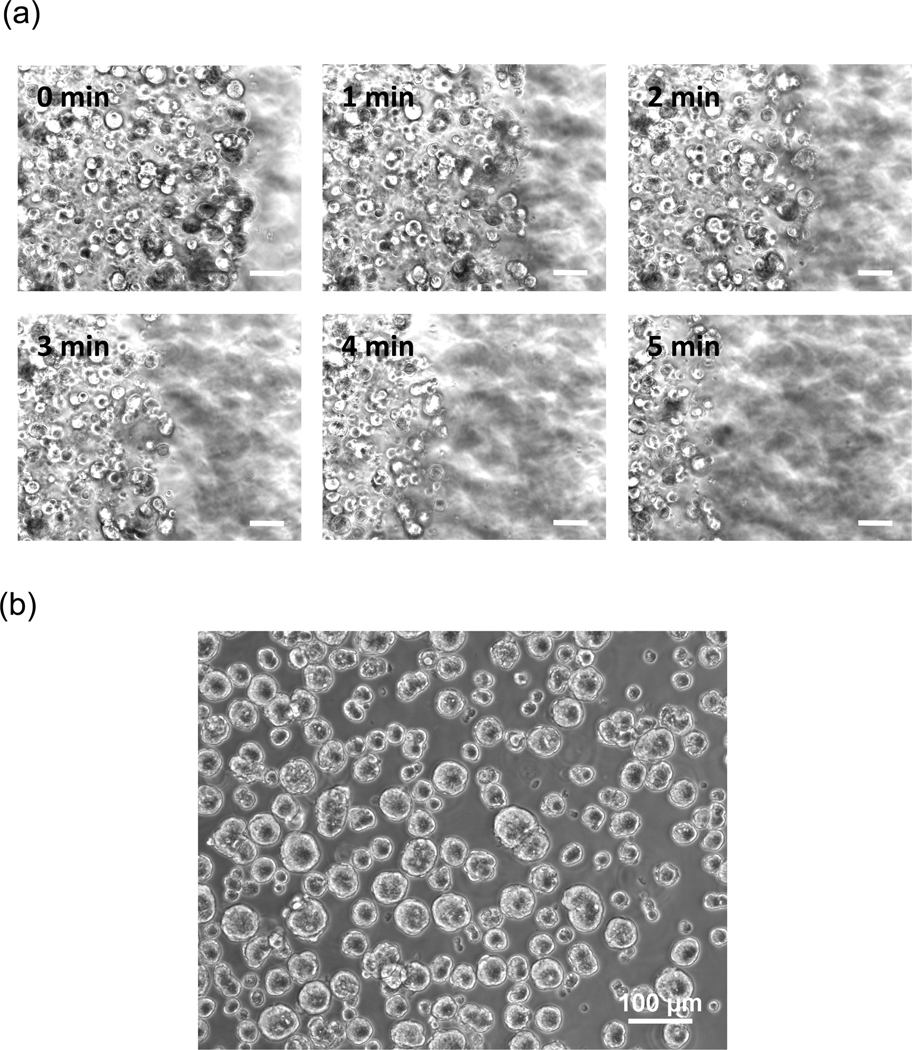

3.7 Rapid recovery of functional β-cell spheroids

The rapid erosion of thiol-ene hydrogels by chymotrypsin provides a mild way of recovering MIN6 β-cell spheroids formed naturally in the hydrogels. The recovery of cell spheroids (under static incubation for imaging and with gentle shaking for biological assays) was conducted after 10 days of 3D culture (Movie S1 and snap shots shown in Figure 6a). The recovered spheroids appeared to be intact and were not affected by the enzymatic action of chymotrypsin (Figure 6b). The size of the recovered cell spheroids were not affected by prolonged (half an hour) chymotrypsin treatment (data not shown).

Figure 6.

(a) Snap shots of chymotrypsin-mediated thiol-ene hydrogel erosion and β-cell spheroids recovery under static incubation. Cells were encapsulated at a packing density of 107 cells/mL and cultured for 10 days. Chymotrypsin was added at 40µM in serum free DMEM. (b) Representative phase contrast image of recovered β-cell spheroids. Complete gel erosion was achieved within 5 minutes (40µM chymotrypsin) at room temperature on an orbital shaker (Scale: 100µM).

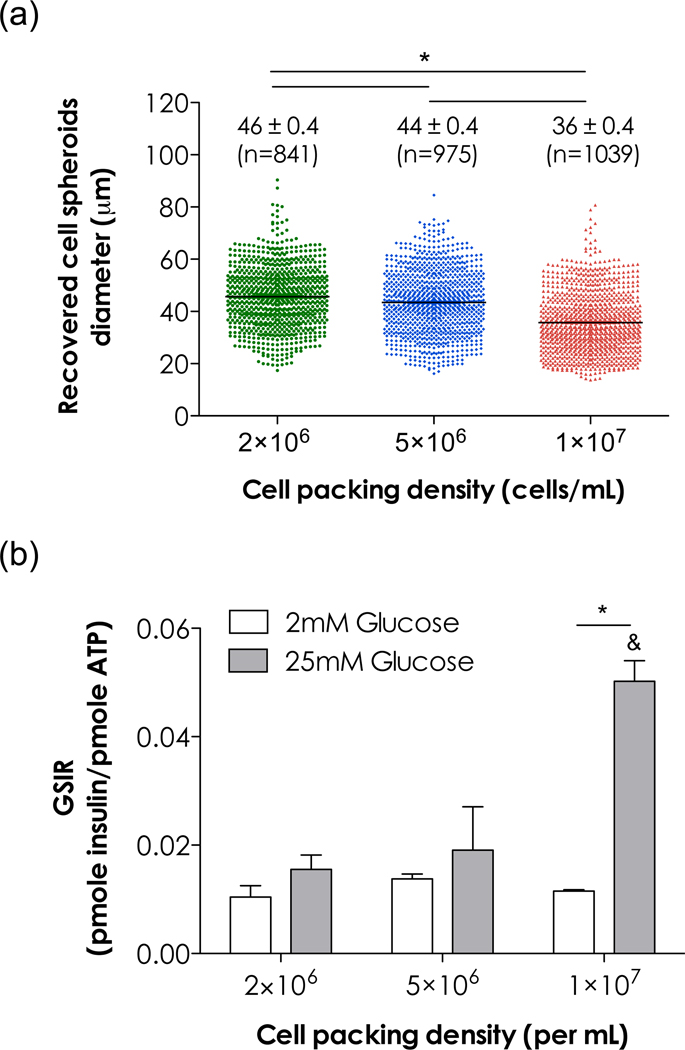

Figure 7a shows the size distribution of recovered cell spheroids formed in PEG4NB hydrogels with different initial cell packing densities. Interestingly, the average diameter of cell spheroids decreased as initial cell packing density. Cells encapsulated at 107 cells/mL formed spheroids with an average diameter of 36 ± 0.4 µm or about 22% smaller than the spheroids formed when encapsulated at 2×106 cells/mL (46 ± 0.4 µm). One potential explanation is that increasing initial cell packing density enhances cell-cell interactions that impose contact inhibition for cell proliferation, thus resulting in smaller cell spheroids. From the perspective of hydrogel crosslinking, it is likely that cells at higher density occupied more volume in a pre-polymer solution, resulting in slight increase in local PEG4NB/peptide macromer concentration and higher crosslinking density after polymerization (the total weight of PEG4NB and volume of pre-polymer solutions were kept constant). Previously, we have estimated that MIN6 β-cells, when encapsulated at 107 cells/mL, occupied approximately 2% of the pre-polymer solution volume [13]. Consequently, cells encapsulated at higher packing density were surrounded by a slightly denser polymer network. While the thiol-ene crosslinking processes did not cause significant cellular damage, the denser local hydrogel mesh inhibited their growth into larger cell spheroids. Future experiments are needed to demonstrate this mechanism.

Figure 7.

Characterization of recovered MIN6 β-cell spheroids. Cell spheroids were recovered from thiol-ene hydrogels using 40µM chymotrypsin after 10 days in vitro culture, (a) Distribution of spheroid diameters, (b) Glucose stimulated insulin release (GSIR) of recovered cell spheroids (N=3, mean ± SEM). Cell packing density refers to the cell density used during encapsulation.

Glucose stimulated insulin release (GSIR) results (Figure 7b) showed that the recovered MIN6 spheroids exhibited glucose stimulated insulin secretion. Notably, cell spheroids recovered from initial packing density of 107 cells/mL showed higher amount of insulin secretion, potentially due to their smaller spheroid diameters. Research has shown that isolated islets with smaller diameters release higher amount of insulin on a per cell basis [37, 38]. The enhancement in insulin secretion from smaller islets or β-cell spheroids at a higher glucose concentration is beneficial for maintaining normal glycemia when transplanting in vivo [39].

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated the cytocompatibility and high gelation efficiency of PEG hydrogels formed by step-growth thiol-ene photopolymerizations. While the viability of pancreatic β-cells was significantly damaged following non-gelling chain-growth photopolymerizations, minimal cellular damage was found in step-growth thiol-ene click reactions. Compared to PEGDA hydrogels with equal functionality and at identical photopolymerization conditions, PEG4NB hydrogels yield higher gel fraction, higher mesh sizes, and higher mechanical properties. Moreover, β-cells encapsulated in PEG4NB hydrogels had much higher viability, compared to cells encapsulated in PEGDA hydrogels, even when the cells were encapsulated at low cell packing density. Finally, the encapsulated β-cells formed viable and functional cell spheroids within thiol-ene hydrogels. These spheroids were rapidly retrieved from chymotrypsin-erodible thiol-ene hydrogels. This diverse and cytocompatible gel platform offers a venue for engineering complex 3D tissues for regenerative medicine applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This project was supported by an NIH/NIBIB R21 grant (R21EB013717), an NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI CO-Pilot grant (UL1RR025780), a faculty start-up fund from the Department of Biomedical Engineering at IUPUI, and a Research Support Funds Grant (RSFG) from the Office of Vice Chancellor for Research at IUPUI. The authors also thank financial support from an UROP research grant (Center for Research and Learning) to AR, and a Commitment to Engineering Excellence Research Fund (Purdue School of Engineering and Technology) to HS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cushing MC, Anseth KS. Hydrogel cell cultures. Science. 2007;316:1133–1134. doi: 10.1126/science.1140171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tibbitt MW, Anseth KS. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009;103:655–663. doi: 10.1002/bit.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin CC, Metters AT. Hydrogels in controlled release formulations: Network design and mathematical modeling. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006;58:1379–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin CC, Anseth KS. PEG hydrogels for the controlled release of biomolecules in regenerative medicine. Pharm. Res. 2009;26:631–643. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9801-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khetan S, Katz JS, Burdick JA. Sequential crosslinking to control cellular spreading in 3-dimensional hydrogels. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1601–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khetan S, Burdick JA. Patterning hydrogels in three dimensions towards controlling cellular interactions. Soft Matter. 2011;7:830–838. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khetan S, Burdick JA. Patterning network structure to spatially control cellular remodeling and stem cell fate within 3-dimensional hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8228–8234. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdick JA, Anseth KS. Photoencapsulation of osteoblasts in injectable RGD-modified PEG hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4315–4323. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang NS, Varghese S, Zhang Z, Elisseeff J. Chondrogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cells in arginine-glycine-aspartate modified hydrogels. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2695–2706. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King WJ, Jongpaiboonkit L, Murphy WL. Influence of FGF2 and PEG hydrogel matrix properties on hMSC viability and spreading. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2010;93A:1110–1123. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin CC, Anseth KS. Glucagon-like peptide-1 functionalized PEG hydrogels promote survival and function of encapsulated pancreatic beta-cells. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2460–2467. doi: 10.1021/bm900420f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin CC, Anseth KS. Controlling affinity binding with peptide-functionalized poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009;19:2325–2331. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin CC, Anseth KS. Cell-cell communication mimicry with poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for enhancing beta-cell function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:6380–6385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014026108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CC, Boyer PD, Aimetti AA, Anseth KS. Regulating MCP-1 diffusion in affinity hydrogels for enhancing immuno-isolation. J. Control. Release. 2010;142:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin CC, Metters AT, Anseth KS. Functional PEG-peptide hydrogels to modulate local inflammation induced by the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF alpha. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4907–4914. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuttelman CR, Tripodi MC, Anseth KS. Synthetic hydrogel niches that promote hMSC viability. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber LM, Hayda KN, Haskins K, Anseth KS. The effects of cell-matrix interactions on encapsulated beta-cell function within hydrogels functionalized with matrix-derived adhesive peptides. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3004–3011. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber LM, Lopez CG, Anseth KS. Effects of PEG hydrogel crosslinking density on protein diffusion and encapsulated islet survival and function. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2009;90A:720–729. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Halevi AE, Nuttelman CR, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:5005–5010. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz MP, Fairbanks BD, Rogers RE, Rangarajan R, Zaman MH, Anseth KS. A synthetic strategy for mimicking the extracellular matrix provides new insight about tumor cell migration. Integr. Biol. 2010;2:32–40. doi: 10.1039/b912438a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benton JA, Fairbanks BD, Anseth KS. Characterization of valvular interstitial cell function in three dimensional matrix metalloproteinase degradable PEG hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6593–6603. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aimetti AA, Machen AJ, Anseth KS. Poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels formed by thiol-ene photopolymerization for enzyme-responsive protein delivery. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6048–6054. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson SB, Lin CC, Kuntzler DV, Anseth KS. The performance of human mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in cell-degradable polymer-peptide hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3564–3574. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terella A, Mariner P, Brown N, Anseth K, Streubel SO. Repair of a calvarial defect with biofactor and stem cell-embedded polyethylene glycol scaffold. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2010;12:166–171. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2010.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hume PS, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Functionalized PEG hydrogels through reactive dip-coating for the formation of immunoactive barriers. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6204–6212. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruise GM, Scharp DS, Hubbell JA. Characterization of permeability and network structure of interfacially photopolymerized poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1287–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6702–6707. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canal T, Peppas NA. Correlation between mesh size and equilibrium degree of swelling of of polymeric metworks. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1989;23:1183–1193. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820231007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui HX, Nourparvar A, Zhao XN, Perfetti R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits apoptosis of insulin-secreting cells via a cyclic 5 '-adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A- and a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1444–1455. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimoto K, Suzuki K, Kizaki T, Hitomi Y, Ishida H, Katsuta H, et al. Gliclazide protects pancreatic beta-cells from damage by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;303:112–119. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou N, Torii S, Saito N, Hosaka M, Takeuchi T. Reactive oxygen species-mediated pancreatic beta-cell death is regulated by interactions between stress-activated protein kinases, p38 and C-jun N-terminal kinase, and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1654–1665. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellis RJ. Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:597–604. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin-Gibson S, Jones RL, Washburn NR, Horkay F. Structure-property relationships of photopolymerizable poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate hydrogels. Macromolecules. 2005;38:2897–2902. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bundy HF. Chymotrypsin-catalyzed hydrolysis of N-acetyl- and N-benzoyl-L-Tyrosine p-nitroanilides. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1963;102:416–422. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(63)90249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris JL, Backes BJ, Leonetti F, Mahrus S, Ellman JA, Craik CS. Rapid and general profiling of protease specificity by using combinatorial fluorogenic substrate libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:7754–7759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140132697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appel W. Chymotrypsin: Molecular and catalytic properties. Clin. Biochem. 1986;19:317–322. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(86)80002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacGregor RR, Williams SJ, Tong PY, Kover K, Moore WV, Stehno-Bittel L. Small rat islets are superior to large islets in in vitro function and in transplantation outcomes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;290:E771–E779. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00097.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita Y, Takita M, Shimoda M, Itoh T, Sugimoto K, Noguchi H, et al. Large human islets secrete less insulin per islet equivalent than smaller islets in vitro. Islets. 2011;3:1–5. doi: 10.4161/isl.3.1.14131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehmann R, Zuellig RA, Kugelmeier P, Baenninger PB, Moritz W, Perren A, et al. Superiority of small islets in human islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2007;56:594–603. doi: 10.2337/db06-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.