Abstract

Our previous studies have shown that recombinant multivalent vaccines containing amino-terminal M protein fragments from as many as 26 different serotypes of group A streptococci (GAS) evoked opsonic antibodies in animals and humans. In the present study, we constructed a new 30-valent vaccine containing M protein peptides from GAS serotypes prevalent in North America and Europe. The vaccine was immunogenic in rabbits and evoked bactericidal antibodies against all 30 vaccine serotypes of GAS. In addition, the vaccine antisera also contained significant levels of bactericidal antibodies against 24 of 40 non-vaccine serotypes of GAS. These results indicate that the potential efficacy of the new multivalent vaccine may be greater than predicted based on the "type-specific" M peptides represented.

Introduction

Efforts to develop safe and effective vaccines to prevent group A streptococcal (GAS) infections have been ongoing for decades. Although there are a number of GAS antigens that have been identified as potential vaccine components [1], the lead candidates are the type-specific peptides representing the amino-terminal regions of the surface M proteins [2, 3]. These regions of M proteins have been shown to evoke antibodies with the greatest bactericidal (protective) activity and are least likely to cross-react with human tissues [4]. Our approach has been to construct recombinant hybrid proteins containing M protein peptides that are combined into multivalent vaccines designed to elicit opsonic antibodies against epidemiologically important serotypes of group A streptococci [5, 6].

In previous reports, we described the immunogenicity of a 26-valent M protein-based vaccine in pre-clinical [6] and clinical studies [3]. This vaccine was designed based on the available epidemiology and serotype prevalence of GAS infections in North America [7]. More recent epidemiologic studies have provided additional data from North America and Europe [8–10], as well as from some developing countries [11]. We have used these results to refine the composition of the 30-valent vaccine to more adequately represent the epidemiology of pharyngitis and invasive GAS infections. The vaccine is composed of four different hybrid proteins that contain seven or eight different M protein fragments linked in tandem. When formulated with alum, the vaccine was highly immunogenic in rabbits and evoked broadly protective antibodies, as determined by indirect bactericidal assays. In addition, the vaccine elicited bactericidal antibodies against a significant number of "non-vaccine" serotypes, indicating that the potential efficacy of the 30-valent vaccine may extend well beyond the serotypes represented by the subunit M peptides.

Materials and Methods

Vaccine design

M peptides were selected from serotypes of GAS based on the epidemiology of : 1) pharyngitis in pediatric subjects in North America [8], 2) invasive GAS infections, as reported by the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network, supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [9], and 3) invasive infections in Europe reported by the StrepEuro consortium [10]. Also included in the 30-valent vaccine are M peptides from serotypes of GAS that are currently or have been historically considered "rheumatogenic" [12] and the amino-terminal peptide fragment of Spa18, a protective antigen that is expressed by at least several serotypes of group A streptococci [13].

The amino acid sequences of the M proteins selected for inclusion in the vaccine were obtained from the CDC emm typing center website (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/emmtypes.html). When sub-types were present, the sequence of the M protein from predominant subtype was selected. The amino-terminal regions of the mature M proteins (and Spa) were searched by BlastP for homology against human proteins in the GenBank database. Amino-terminal sequences having five or more contiguous amino acid matches with human proteins were excluded.

Construction and expression of recombinant vaccine proteins

The specific 5’ sequences of each emm gene were used to design four hybrid DNA molecules. Each gene was designed to contain 7 or 8 emm gene fragments linked in tandem (Fig. 1), an upstream T7 promoter, and a 3' poly-histidine motif followed by a stop codon. The N-terminal peptide of each vaccine protein was reiterated in the C-terminal location. This design was based on our previous observation that the C-terminal peptide may function to "protect" the penultimate peptide from proteolysis thus preserving its immunogenicity [14]. Unlike the 26-valent vaccine, no linking codons were inserted between the emm sequences. Optimization of codons for E. coli was accomplished prior to synthesis rather than by subsequent site mutation. The DNA was chemically synthesized, ligated into pUC57 (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ) and the integrity of the synthetic gene sequences was verified by sequencing using the ABI dye termination method. Expression of each multivalent fusion protein was detected by SDS-PAGE analysis using whole cell lysates before and after IPTG induction.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the four proteins comprising the 30-valent M protein-based GAS vaccine. M subtypes were the parent sequence type (“.0”) unless otherwise indicated.

ELISA antigens

Individual recombinant dimeric peptides comprising the vaccine component peptides were expressed and purified to use as serologic reagents, as previously described [6]. In addition, seven new M peptides were chemically synthesized for these studies (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ).

Purification of recombinant multivalent vaccine component fusion proteins

Each component fusion protein was purified separately according to procedures previously reported [6]. Purity was monitored using SDS-PAGE and fractions containing recombinant vaccine protein were pooled and stored at −20°C until use.

Vaccine formulation and immunization of rabbits

The four purified vaccine proteins were mixed in equimolar amounts and adsorbed to alum (Rehydragel, low viscosity, Reheis, Inc., Berkeley Heights, NJ). Vaccines were formulated so that each 0.5 ml dose contained 200 µg, 400 µg, 800 µg, or 1000 µg of protein and approximately equal amounts of alum by weight. Groups of three New Zealand white rabbits were each immunized with one of the four vaccine doses via the intramuscular route at 0, 4, and 8 weeks [14]. Serum was obtained prior to the first injection and two weeks after the final injection.

Detection of M peptide antibodies

ELISAs were performed using preimmune and immune rabbit sera by methods previously described [14]. The purified recombinant dimeric M peptides or synthetic peptides comprising the vaccine subunits were used as solid-phase antigens.

Indirect bactericidal tests

Bactericidal assays were performed as previously described [6]. Briefly, 0.05 ml of Todd-Hewitt broth containing bacteria was added to 0.1 ml of test serum and 0.35 ml of lightly heparinized non-immune human blood and the mixture was rotated for three hours at 37°C. Then 0.1 ml aliquots of this mixture were added to melted sheep’s blood agar, pour plates were prepared, and viable organisms (CFU) were counted after overnight incubation at 37°C. For each serotype tested, three different inocula were used to assure that the growth in blood containing preimmune serum was optimal and quantifiable. The results were expressed as percent killing, which was calculated using the following formula: [(CFU after three hours growth with preimmune serum) − (CFU after three hours growth with immune serum) ÷ CFU after three hours growth with preimmune serum] × 100. Only those assays that resulted in growth of the test strain to at least seven generations in the presence of preimmune serum were used to express percent killing in the presence of immune serum.

Assays for tissue cross-reactive antibodies

Immune sera were tested for the presence of tissue cross-reactive antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence assays using frozen sections of human heart, brain, and kidney by methods previously described [3].

Results

Composition of the multivalent M protein-based vaccine

Epidemiologic data from the North American pharyngitis study [7, 8], the CDC's ongoing ABCs surveillance in the US [9] and the StrepEuro study of invasive GAS strains [10] were used to select the M serotypes of GAS represented in the 30-valent vaccine (Fig. 1). The vaccine serotypes accounted for 98% of all cases of pharyngitis in the US and Canada, 90% of invasive disease in the US and 78% of invasive disease in Europe. The serotypes represented in the 30-valent vaccine that were not contained in the 26-valent vaccine are: M4, M29, M73, M58, M44, M78, M118, M82, M83, M81, M87, and M49. Serotypes represented in the 26-valent vaccine that are not components of the 30-valent vaccine are: M1.2, M43, M13, M59, M33, M101, and M76.

Immunogenicity of the 30-valent vaccine in rabbits

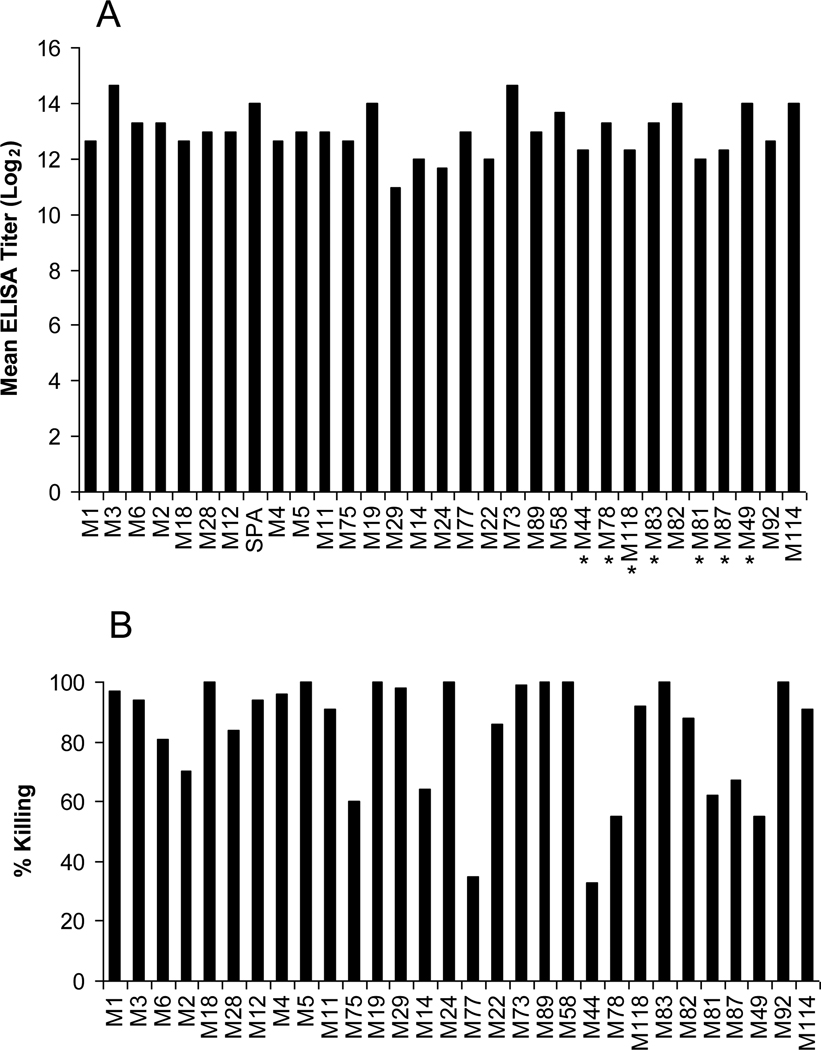

The four recombinant vaccine proteins that comprised the 30-valent vaccine were purified and formulated on alum in four different concentrations. Dose response studies were conducted using sets of three rabbits that received three injections of either 200 µg, 400 µg, 800 µg or 1,000 µg at times 0, 4 weeks and 8 weeks. Serum obtained 2 weeks after the final injection was assayed by ELISA using the vaccine subunit peptides as test antigens. A dose-response curve was determined by calculating the average geometric mean antibody titer for the three antisera against the vaccine subunit peptides: 200 µg dose group = 5651 average antibody titer, 400 µg = 8868, 800 µg = 9619, and 1,000 µg = 8071. None of the immune sera contained antibodies that cross-reacted with human brain, kidney or heart, as determined by indirect immunofluorescence assays. Based on the dose-response curve, all subsequent experiments were performed using antisera from rabbits that received the 800 µg dose of vaccine, which was highly immunogenic and evoked significant levels of antibodies against each subunit peptide contained in the vaccine (Fig. 1A).

Bactericidal antibodies evoked by the 30-valent vaccine

The 800 µg dose of vaccine elicited significant levels of bactericidal antibodies against the vaccine serotypes of GAS, as determined by in vitro opsonophagocytic killing assays in whole human blood (Fig. 2B). Bactericidal killing of >40% was observed with 28/30 vaccine serotypes of GAS using serum from one of the immunized rabbits. The average killing observed against all vaccine serotypes was 83%.

Fig. 2.

(2.A.) Geometric mean antibody levels (Log2) evoked in three rabbits after immunization with three 800 µg doses of the 30-valent GAS vaccine. Solid-phase antigens were recombinant dimeric peptides or synthetic peptides (indicated by an asterisk) copying the sub-peptides. (2.B.) Bactericidal antibodies evoked by 30-valent M protein-based GAS vaccine. Immune serum from one of the rabbits immunized with 800 µg doses of the vaccine was used in bactericidal assays against all vaccine serotypes of GAS. Percent killing was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Bactericidal activity of the vaccine antisera against non-vaccine serotypes

The immune sera against the 30-valent vaccine were also used in indirect bactericidal assays against a panel of GAS serotypes that were not represented in the vaccine. Bactericidal activity of >40% was observed against 24/40 serotypes selected from our laboratory collection (Fig. 3). The average observed for the 24 serotypes that displayed >40% killing was 78% killing and for all 40 serotypes tested was 54%.

Fig. 3.

Bactericidal antibodies evoked by 30-valent vaccine against non-vaccine serotypes of GAS.

Discussion

Safe and effective vaccines to prevent GAS infections could potentially have a significant impact on the health of millions of people around the world. The 30-valent vaccine described in the present study was constructed based on the most comprehensive GAS epidemiologic data available from North America and Europe. The major burden of disease in these and other economically developed regions is uncomplicated pharyngitis and serious, invasive infections [15]. The potential efficacy of the new vaccine in these geographic regions has been optimized by closely matching the formulation of the vaccine serotypes with the epidemiology of GAS diseases. In addition, the 30-valent vaccine now includes the protective M antigen of type 4 GAS, which was not identified prior to the construction of the previous 26-valent vaccine. Serotype 4 accounts for approximately 9% of uncomplicated GAS pharyngitis in North America and 5% of invasive disease in Europe [8, 10]. Based on the pre-clinical results described in the current study, together with the previously reported results of clinical trials using the 26-valent vaccine [3], we conclude that the 30-valent vaccine is optimally formulated to potentially have broad efficacy in reducing the burden of uncomplicated and invasive GAS infections in North America and Europe.

The immunogenicity of the 30-valent vaccine in rabbits was similar to that previously described for the 26-valent vaccine. The 30-valent vaccine evoked significant levels of antibodies against all component peptides, as determined by ELISA. As described previously for the 26-valent vaccine [6], in the present study there was generally a good correlation between antibody titer and functional bactericidal antibody activity. However, as with the 26-valent vaccine, 2 of the M peptides in the 30-valent vaccine (from serotypes 44 and 77) evoked low levels of bactericidal antibodies. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear but may be related to individual differences in immune responsiveness and not necessarily to the presence or absence of protective epitopes within the M peptides. This explanation is supported by the observation that all component peptides of the 26-valent vaccine were later shown in clinical studies to evoke opsonic antibodies in adult volunteers [3].

The global burden of GAS infections is most significant in developing countries where acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) are rampant [15]. Vaccine prevention of the infections that trigger ARF using M protein-based vaccines has been considered a challenge because the GAS emm types present in developing countries differ compared to economically developed areas of the world [11]. However, our results showing that the new 30-valent vaccine evokes cross-opsonic bactericidal antibodies against a significant number of non-vaccine serotypes of GAS may ultimately result in greater potential vaccine efficacy in developing countries. The molecular basis for the cross-reactive opsonic antibodies is not yet known but is now the subject of investigation. Protein sequence homology searches using NCBI blast algorithms of vaccine peptide sequences compared to N-terminal M protein sequences from non-vaccine serotypes indicated the presence of shared sequences that could account for cross-protective epitopes (unpublished observation). In addition, it is possible that M-related proteins or other surface proteins on the bacterial surface may contain cross-opsonic epitopes recognized by the vaccine antisera.

Our ongoing prospective studies of the epidemiology of GAS pharyngeal infections in Bamako, Mali and the Vanguard Community of South Africa indicate that the 30-valent vaccine serotypes account for 40% and 59%, respectively, of all pharyngeal isolates obtained from school-age children (personal communication, Karen Kotloff, University of Maryland, and Bongani Mayosi, University of Cape Town, respectively). Further comprehensive studies to determine the extent of cross-opsonic antibodies evoked by the 30-valent vaccine against GAS isolates from developing countries should define the potential efficacy of the vaccine in areas of the world where the molecular epidemiology of GAS infections is not optimally aligned with the vaccine composition. Although a human immune correlate of protection has not been firmly established for GAS infection, in vitro data demonstrating that the 30-valent vaccine evokes cross-opsonic bactericidal antibodies against a significant number of GAS isolates present in a population could support late-stage clinical trials to determine efficacy. Vaccine prevention of even a fraction of serious GAS infections and ARF/RHD could have a major impact on the health of millions of people.

A new recombinant 30-valent M protein-based group A streptococcal vaccine

Vaccine design based on current epidemiology of pharyngeal and invasive infections

Bactericidal antibodies evoked against all vaccine serotypes of streptococci

Vaccine antisera were bactericidal against a number of non-vaccine serotypes

Acknowledgments

Financial support: National Institutes of Health, AI-010085 (J.B.D.) and AI-060592 (J.B.D.). William Walton was the recipient of a medical student summer fellowship supported by NIH 5T35DK007405.

We appreciate the expert technical assistance provided by Valerie Long and the expert secretarial assistance of Deborah Bueltemann in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steer AC, Batzloff MR, Mulholland K, Carapetis JR. Group A streptococcal vaccines: facts versus fantasy. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(6):544–552. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328332bbfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotloff KL, Corretti M, Palmer K, Campbell JD, Reddish MA, Hu MC, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant multivalent group a streptococcal vaccine in healthy adults: phase 1 trial. JAMA. 2004;292(6):709–715. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNeil SA, Halperin SA, Langley JM, Smith B, Warren A, Sharratt GP, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 26-valent group A streptococcus vaccine in healthy adult volunteers. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(8):1114–1122. doi: 10.1086/444458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dale JB. Current status of group A streptococcal vaccine development. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;609:53–63. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73960-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dale JB. Multivalent group A streptococcal vaccines. Inf Dis Clin N Amer. 1999;13:227–243. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu M, Walls M, Stroop S, Reddish M, Beall B, Dale J. Immunogenicity of a 26-Valent Group A Streptococcal Vaccine. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2171–2177. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2171-2177.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shulman ST, Tanz RR, Kabat W, Kabat K, Cederlund E, Patel D, et al. Group A streptococcal pharyngitis serotype surveillance in North America, 2000–2002. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):325–332. doi: 10.1086/421949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shulman ST, Tanz RR, Dale JB, Beall B, Kabat W, Kabat K, et al. Seven-year surveillance of north american pediatric group a streptococcal pharyngitis isolates. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):78–84. doi: 10.1086/599344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, Lynfield R, Gershman K, Craig A, et al. The epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infection and potential vaccine implications: United States, 2000𠄣2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):853–862. doi: 10.1086/521264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luca-Harari B, Darenberg J, Neal S, Siljander T, Strakova L, Tanna A, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of severe Streptococcus pyogenes disease in Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):1155–1165. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02155-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steer AC, Law I, Matatolu L, Beall BW, Carapetis JR. Global emm type distribution of group A streptococci: systematic review and implications for vaccine development. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2009;9(10):611–616. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shulman ST, Stollerman G, Beall B, Dale JB, Tanz RR. Temporal changes in streptococcal M protein types and the near-disappearance of acute rheumatic fever in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(4):441–447. doi: 10.1086/499812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dale JB, Chiang EY, Liu SY, Courtney HS, Hasty DL. New protective antigen of group A streptococci. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1261–1268. doi: 10.1172/JCI5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dale JB. Multivalent group A streptococcal vaccine designed to optimize the immunogenicity of six tandem M protein fragments. Vaccine. 1999;17:193–200. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2005;5(11):685–694. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]