Abstract

Objective

This study compared glycemic control in finger tip versus forearm sampling methods of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG).

Research Design and Methods

One hundred seventy-four insulin-using patients with type 2 diabetes were randomized to SMBG using either finger-tip testing (FT) or forearm alternative site testing (AST) and followed up for 7 months. Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) was measured at baseline, month 4, and month 7. The study was designed to test the noninferiority of the AST method for the primary end point of change in HbA1C from baseline to month 7. Adherence with the testing schedule and frequency of hypoglycemic episodes were also measured.

Results

The FT (n = 85) and AST (n = 89) groups each had significant decreases in mean HbA1C from baseline to month 7 (FT, −0.4 ± 1.4%, P = 0.008; AST, −0.3 ± 1.2%, P = 0.045), and noninferiority between groups was demonstrated with a margin of equivalence of 0.5 (P = 0.043). There was no observable difference in HbA1C change between the groups (P = 0.442). Adherence was better in the FT (87%) than the AST (78%) group (P = 0.003), which may have been because of the difficulty some subjects had in obtaining blood samples for AST. The number of hypoglycemic episodes was too small to assess for a difference between groups.

Conclusions

SMBG by the AST, rather than FT, method did not have a detrimental effect on long-term glycemic control in insulin-using patients with type 2 diabetes. Although adherence with testing was expected to be better in the AST group, it was actually better in the FT group.

Introduction

Individuals with diabetes have traditionally obtained samples for self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) using lancets to prick their fingertips, but this process can be painful and may be a barrier to testing with adequate frequency.1 In the last several years, a new generation of SMBG devices has been developed that allows the use of far smaller volumes of blood than previous devices (<1 μL). These newer meters allow patients to perform SMBG using samples obtained from skin sites other than the fingertip, such as the forearm or thigh, which are less vascular than the fingertips and yield less blood after skin puncture. They are also less densely innervated with pain receptors than the fingertips, which allows for less painful sampling.2,3 Alternative site testing (AST) has been widely marketed by the manufacturers of SMBG meters as a less painful alternative to finger-tip testing (FT). It has also been suggested that AST might improve patients' adherence to SMBG regimens, potentially improving their glycemic control.2,4–7 However, whether the option to use AST actually improves adherence has not been adequately answered. One small nonrandomized study suggested that it does,6 while a larger crossover study showed no such difference.8

Thus far in the evaluation of AST it has also been noted that this method can yield results that are significantly different from both FT and reference blood glucose measures at times that blood glucose is changing rapidly, such as after a glucose load,5,9,10 after meals,4,11,12 after the administration of insulin,9,10 and after exercise.11 These findings have been attributed to a delayed equilibration of arm and thigh skin with arterial blood glucose resulting from lesser blood flow.10 Manufacturers of SMBG devices have recommended preparatory rubbing or heating of AST sites to increase blood flow and mitigate the difference due to equilibration time, but this may not be effective.11 No significant difference has been found between AST and FT measurements in the fasting or steady state.4,5,11–14

The delay in equilibration in arm and thigh testing appears to be greatest between 60 and 90 min after a meal or glucose load4,5,9–12 but may persist for as long as 240 min after a combination of glucose and insulin.10 These findings have led to serious concerns about the potential failure of AST to identify hypoglycemia,7,9,10,14,15 and the phenomenon has led the Food and Drug Administration to recommend clear labeling and instructions for patients not to use AST when hypoglycemia is suspected or at times when blood glucose may be changing rapidly.16 Another potential consequence of the lag in AST equilibration is that postprandial blood glucose levels could be systematically underestimated. Postprandial measurements are being increasingly used in clinical practice because they contribute significantly to long-term control17–19 and can guide later mealtime insulin dosing. Underestimation in measuring postprandial blood glucose with AST could hamper efforts at glycemic control.

When AST is used in clinical care, it is generally introduced as an option for patients to use for some but not all of their SMBG tests in order to reduce the cumulative discomfort from multiple finger sticks. Our goal was to explore the question of whether changing from exclusive finger testing, the standard of care in patients with diabetes using insulin, to introduce an option to use AST in addition to FT would lead to worsened control as a result of differences between AST and FT readings. The only previous study to have compared long-term control between these two methods found no difference between them, but its study population was in such good initial control that a meaningful difference would have been difficult to detect.8 We hypothesized that the option to use AST would not lead to poorer glycemic control as assessed by hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) in a diverse population of insulin-using patients with type 2 diabetes with varying levels of initial glycemic control. As a secondary consideration, we planned to track adherence to testing to determine whether use AST might improve adherence to testing and thereby have the potential to positively affect long-term glycemic control. The results were previously presented in abstract form at the 2006 Endocrine Society Annual Meeting.20

Research Design and Methods

Population

The study was conducted between July 2003 and December 2005 at Boston University Medical Center, Boston, MA, with subjects recruited from the Center for Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition and Weight Management and affiliated primary care practices. Newspaper advertising was also employed to recruit subjects from outside the medical center. Potential subjects were eligible for participation if they were 18–70 years of age with type 2 diabetes, using insulin, and performing SMBG measurements. Exclusion criteria included type 1 diabetes, prior use of AST, pregnancy, and serious comorbid illness (unstable cardiovascular disease or metastatic cancer). Potential subjects were also excluded if, within the past year, they had a hypoglycemic episode requiring urgent medical attention, resulting in cognitive impairment, or a lack of symptoms during a hypoglycemic episode. The Institutional Review Board at Boston University and the Food and Drug Administration's Research Involving Human Subjects Committee each approved the protocol. All subjects gave verbal and written informed consent prior to study entry.

Study design

This was a randomized, parallel group trial consisting of nine visits. At the screening visit, information was collected on baseline characteristics as listed in Table 1, and subjects were asked to return approximately 2 weeks later for the randomization/training visit. Those who arrived for this visit were randomized to either the FT or the arm AST group using a block randomization stratified by six strata of initial HbA1C to ensure similar mean initial HbA1C in both groups. The strata of HbA1C (%) were <7.0%, 7.0–7.5%, 7.5–8.0%, 8.0–8.5%, 8.5–9.5%, and >9.5%. All SMBG monitoring in the study was performed using the OneTouch® Ultra® device (Life-scan®, Milpitas, CA). Subjects not already using this device were provided with a new one. When subjects were not able to obtain an adequate number of test strips as part of their usual health coverage, they were provided with free strips donated by the manufacturer.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in the FT and Forearm AST Groups

| FT group (n = 85) | AST group (n = 89) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.2 ± 9.5 | 53.1 ± 10.2 | 0.959 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 35.9 ± 9.6 | 35.9 ± 9.2 | 0.975 |

| Waist circumference (inches) | 44.4 ± 7.2 | 45.3 ± 6.8 | 0.412 |

| Female | 52 (61%) | 42 (47%) | 0.064 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| African American | 39 (46%) | 48 (54%) | |

| Black Caribbean | 7 (8%) | 9 (10%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 21 (25%) | 24 (27%) | 0.162a |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 (14%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Asian/Pacific | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Highest educational level achieved | |||

| Completed high school/GED | 30 (35%) | 35 (39%) | |

| Some post-secondary | 34 (40%) | 33 (37%) | 0.972 |

| Baseline HbA1C (%) | 8.8 ± 2.2 | 8.7 ± 2.1 | 0.649 |

| Years with diabetes | 12.0 ± 9.8 | 12.7 ± 9.1 | 0.643 |

| SMBG tests prior to study | |||

| <1 per day | 8 (9%) | 10 (11%) | |

| 1–2 per day | 40 (47%) | 51 (57%) | 0.258 |

| ≥3 or more per day | 37 (44%) | 28 (32%) | |

| Frequency of insulin injections | |||

| 1 per day | 12 (14%) | 12 (14%) | |

| 2 per day | 37 (44%) | 34 (38%) | 0.633 |

| ≥3 per day | 33 (39%) | 37 (42%) | |

| Using oral diabetes agent (plus insulin) | 52 (63%) | 47 (57%) | 0.374 |

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD values, and categorical variables as n (%). No difference between groups was considered significant. Baseline characteristics were also compared between the total number of completers (n = 135) versus non-completers (n = 39). Non-completers were slightly younger, on average, than completers (50.0 vs. 54.1 years old, P = 0.02) and had a trend towards fewer insulin injections per day (2.3 ± 0.8 vs. 2.6 ± 1.1, P = 0.10). There were no other significant differences noted in baseline characteristics between completers and non-completers, including initial mean HbA1C (8.76 ± 2.10% and 8.72 ± 2.22%, respectively).

By Fisher's Exact Test.

Once randomized, each subject received a 30-min training session from a qualified diabetes nurse educator in the use of the SMBG device, including device calibration and settings adjustment. For subjects randomized to the AST group, the training also included instruction on obtaining samples from the forearm. Subjects in the AST group were asked to use AST as much as possible; however, because of the potential limitations of AST in detecting hypoglycemia, they were instructed to use FT when experiencing symptoms of hypoglycemia and to repeat any AST reading <5.55 mmol/L using FT. They were also told that if they had difficulties obtaining a blood sample from arm puncture on any particular occasion, it was acceptable to substitute a finger test. As intended, this resulted in a mixture of arm and finger testing in the AST group, which is consistent with actual clinical use of AST.

Subjects were given standardized SMBG log sheets that prompted them to test a minimum of three times per day: before breakfast, before dinner, and 2 h after dinner. The log sheets were designed to allow some flexibility such that the subject or their diabetes provider could alter the timing of tests if the individual subject's meal or insulin dosing schedule so required. Space was also provided to record test results for episodes of suspected hypoglycemia. Adherence was measured by counting the number of tests recorded, regardless of timing or method, as well as the number of tests requested for each log sheet (21 for a full week). When a test was repeated at an individual time point because of suspicion of hypoglycemia, only one test was counted.

Subjects were asked to return for study visits at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 months after the randomization/training visit. At each follow-up visit the study coordinator collected completed SMBG log sheets and gave out new sheets for use until the next visit. At each visit the study coordinator also recorded the 30-day glucose average from the SMBG device. At the 1-, 3-, and 5-month visits, subjects were also seen by one of nine diabetes care providers (physician or nurse practitioner). Subjects were asked to show their SMBG log sheets from the preceding month to the provider who used this information to modify the treatment regimen as part of their routine diabetes care. Because of the nature of the intervention, neither subjects nor providers could be blinded to group assignment. At months 4 and 7 subjects had blood drawn for HbA1C measurement. These HbA1C values were therefore obtained 3 and 6 months after the first provider visit in which providers had the opportunity to make management decisions based on study SMBG values. HbA1C measurements were made by gas chromatography using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Variant V-II instrument. Subjects were compensated with a total of $170 for participation.

Predetermined withdrawal criteria included a serious hypoglycemic episode during the course of the study (defined as hypoglycemia requiring urgent medical attention or causing seizure or loss of consciousness) or inability to comply with the intended timeline.

Sample size and statistical analysis

The primary hypothesis was that glycemic control in the AST group would not be meaningfully worse than in the FT group. In planning for the noninferiority test we defined a clinically significant difference in HbA1C, the margin of equivalence, to be 0.5%. We powered our study to test the hypothesis that the change from baseline to month 7 HbA1C measurement in the AST group would be no more than 0.5 units higher (worse) than in the FT group. Assuming an SD in HbA1C change of 1.3 (which was an estimate obtained from review of multiple studies using HbA1C as an end point) and using a one-sided rejection rule with alpha = 0.05, we calculated that a sample of 66 subjects in each group completing the study would result in 71% power to detect noninferiority, with margin of equivalence = 0.5.

The goals for diabetes management depend on the level of control already achieved. For patients already in good control, the goal is to maintain the same level of control, and for those in poor control, clinicians strive to improve the HbA1C. Therefore, post hoc analyses were performed to compare the difference in HbA1C change between the two groups stratified by initial level of glycemic control. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (PC-SAS version 8, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables were assessed for normality of distribution and compared using two-tailed t tests or analysis of variance unless otherwise noted. The paired-sample t test was used for within-group comparisons, and independent sample t test was used to compare between groups. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test unless otherwise noted. All significance tests were performed at the alpha = 0.05 level.

Results

Population characteristics

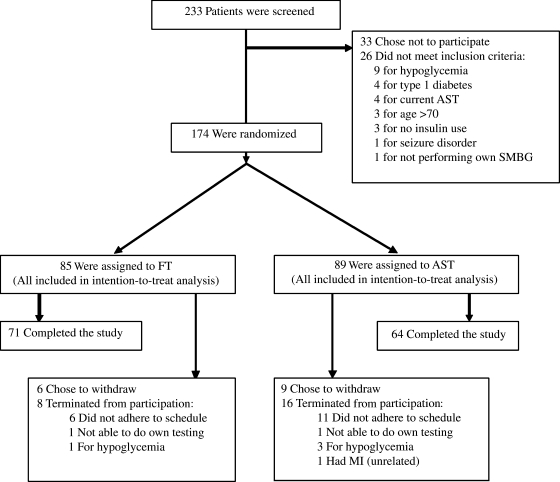

Two hundred thirty-three potential subjects were screened in person. Of these, 26 were ineligible (Fig. 1). Of the 233 patients screened, 207 expressed initial interest. One hundred seventy-four returned for the randomization visit and were enrolled at that time; 85 were randomized to the FT group and 89 to the arm AST group. Of those randomized, 71 (83%) in the FT group and 64 (72%) in the AST group completed the study. The higher dropout/withdrawal rate in the AST group approached statistical significance (P = 0.07). Baseline characteristics were similar for the AST and FT groups (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Subject enrollment and follow-up. MI, myocardial infarction.

Correlation between SMBG and HbA1C

HbA1C reflects the average glucose concentration over a 3-month period with weighting toward the most recent blood glucose levels, such that levels within the 1-month prior to the HbA1C analysis account for approximately 50% of the measured value.21 To assess the correlation between month 4 HbA1C and SMBG readings by each testing method, we calculated a weighted average from the monthly 30-day averages generated by the SMBG meters. Thirty-day average SMBG were recorded from each subject's meter at each of the monthly visits for the 3 months prior to the month 4 HbA1C measurement. The weighted average was then calculated as (0.5×month 3 average) + (0.35×month 2 average) + (0.15×month 1 average). HbA1C was highly correlated with the SMBG weighted average in both groups. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) for the FT group was 0.84 (n = 66, P < 0.0001) and for the AST group was 0.73 (n = 64, P < 0.0001).

Long-term glycemic control

The central hypothesis was that glycemic control, as assessed by HbA1C, would not be meaningfully worse in the AST than in the FT group. We tested this with an intention-to-treat, noninferiority analysis. Missing values for month 4 and month 7 HbA1C in subjects who did not complete the study were taken from actual measurements when available in the medical records. When later HbA1C values were not available, the initial HbA1C value was carried forward. For the FT group HbA1C values were based on actual measurements in 94% of subjects at month 4 and 91% at month 7. For the AST group HbA1C values were based on actual measurements in 90% at month 4 and 83% at month 7. The intention-to-treat analysis demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in glycemic control between baseline and month 7 in both groups (Table 2).The noninferiority test was conducted with pooled variance after assessing for equality of variances. We rejected the hypothesis that the change from baseline to month 7 HbA1C for the AST group was at least 0.5 units higher than for the FT group (P = 0.043). There was no significant difference in the degree of improvement between FT and AST groups (P = 0.442) (Table 2).Findings were similar when the analysis was repeated excluding the imputed values for month 7 HbA1C.

Table 2.

Percentage HbA1C over Time by FT Versus AST Groups Stratified by Level of Initial Glycemic Control

| |

|

HbA1C (%) (mean ± SD) |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline (T0) | Month 4 (M4) | Month 7 (M7) | Difference (M7–T0) | P value (M7–T0) | |

| All subjects | ||||||

| FT | 85 | 8.8 ± 2.2 | 8.4 ± 1.9 | 8.4 ± 1.7 | −0.4 ± 1.4 | 0.008 |

| AST | 89 | 8.7 ± 2.1 | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 8.4 ± 1.8 | −0.3 ± 1.2 | 0.045 |

| Good initial control (baseline HbA1C ≤7.0%) | ||||||

| FT | 18 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | 6.8 ± 0.5 | +0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.024 |

| AST | 21 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 0.7 | +0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.040 |

| Intermediate initial control (baseline HbA1C 7.0–8.5%) | ||||||

| FT | 26 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 7.6 ± 1.0 | 7.9 ± 1.1 | +0.1 ± 1.0 | 0.705 |

| AST | 26 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 0.8 | 7.9 ± 0.9 | +0.1 ± 0.9 | 0.493 |

| Poor initial control (baseline HbA1C >8.5%) | ||||||

| FT | 41 | 10.5 ± 1.9 | 9.7 ± 1.8 | 9.5 ± 1.6 | −1.0 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| AST | 42 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 9.5 ± 1.6 | 9.6 ± 1.6 | −0.8 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

There was a statistically significant improvement in HbA1C from T0 to M7 in both the FT and the AST groups but no significant difference between the groups in the magnitude of this change (P = 0.442). Stratification into three levels of initial glycemic control demonstrated that only the stratum in poor control at baseline actually showed improvement during the course of the study. There was no significant difference between randomization groups in the good, intermediate, or poor initial control strata (P = 0.876, 0.839, and 0.413, respectively).

Because the goals of care for patients depend on initial level of glycemic control, we provide an analysis of HbA1C change by group stratified for starting HbA1C (Table 2).For subjects in good initial control (HbA1C <7.0%) there was a slight increase in HbA1C from baseline to month 7 in both the FT and AST groups, but the mean HbA1C remained below 7.0% in both groups. For subjects in intermediate glycemic control (7.0–8.5%) there was no change in HbA1C from baseline in either group, and for subjects in poor control (HbA1C>8.5%) there was a significant improvement in both groups. There was no detectable difference in mean HbA1C or change in HbA1C between the FT and AST groups in any of the strata of initial glycemic control (sign test).

To confirm the lack of difference between FT and AST groups, we categorized subjects into improved, unchanged, or worsened glycemic control by change in HbA1C from baseline to month 7 of 0.25% or more. In the FT group 39 (46%) improved, 19 (22%) were unchanged, and 27 (32%) worsened. In the AST group 39 (44%) improved, 21 (24%) were unchanged, and 29 (33%) worsened. There was no difference in frequencies between groups (P = 0.929).

Adherence to SMBG schedule

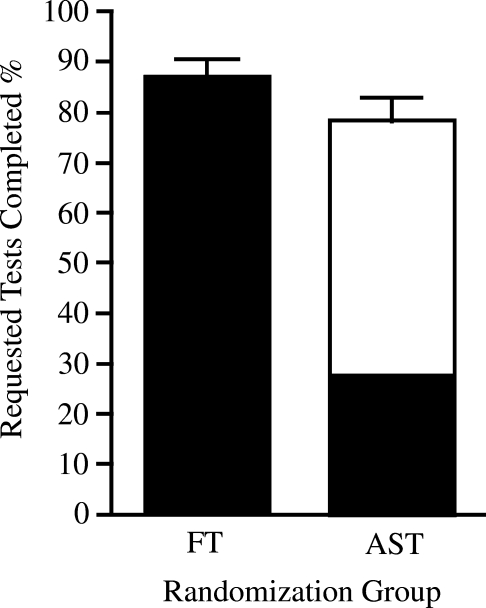

In the AST group subjects were encouraged to use AST as much as possible but were asked to use FT for suspected or possible hypoglycemia or if they had difficulty obtaining blood from the arm. Tests were counted as completed regardless of whether they were performed on the arm or finger. Adherence overall was better in the FT compared to the AST group (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Adherence to testing regimen by randomization group. Mean individual adherence with SMBG regimen in the FT and forearm AST groups was expressed as percentage of requested tests completed. Finger tests are shown in black, arm tests in white. Percentages were obtained by dividing the total number of SMBG tests performed by the total number of tests requested (three tests per day for each day the subject was in the study). The denominator reflected returned log sheets only. Mean percentage of arm tests within the AST group was 65%. Mean overall adherence was higher in the FT group than in the AST group: 87% for FT (95% CI 83.2%, 90.4%) and 78% for AST (95% CI 73.5%, 82.9%) (P = 0.003). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Hypoglycemic episodes

Information on hypoglycemic episodes was collected using a strict definition. Events were only considered to be hypoglycemic episodes if they consisted of hypoglycemic symptoms followed by an SMBG test that confirmed blood glucose <4.44mmol/L. As a result, the number of such events was very small and concentrated in a few individuals. The mean number of hypoglycemic episodes per month was 0.183 in the FT group and 0.176 in the AST group with no significant difference between the two (P = 0.16, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Only three subjects in each group reported an average of more than one hypoglycemic episode per month. Because of the small number of recorded hypoglycemic events we did not have adequate power to detect a difference in the number between groups.

Four subjects were withdrawn from the study because of a severe hypoglycemic episode requiring urgent medical attention: one in the FT group and three (two including seizures) in the AST group. While the occurrence of three out of four severe hypoglycemic events in the AST group is concerning, this is not sufficient to suggest a relationship between AST and such episodes.

Discussion

Glycemic control improved in both groups over the course of their participation in the study, primarily because of substantial improvements in subjects who began the study in poor control (HbA1C>8.5%). Presumably, this was caused by an increased attention to their diabetes and increased frequency of SMBG testing through their participation in the study. We did not observe a difference in the degree of improvement between the FT and AST groups.

Despite the frequently postulated but rarely tested idea that the option for AST might improve adherence with SMBG, AST actually reduced the degree of adherence in our study population (Fig. 1). The fairly regimented nature of our study procedure in which subjects were asked to return their SMBG log sheets to the study coordinator on a monthly basis appeared to lead both groups to have relatively high adherence rates, but the rate in the AST group of 78% tests completed/tests requested was lower than the 87% rate in the FT group (P = 0.003). While this difference is statistically significant, it is small in real terms, and it conflicts with a prevailing opinion that AST can be expected to improve adherence with SMBG. One possible explanation is that subjects in the AST group frequently reported difficulty in obtaining blood from the arm despite having had specific training in this method with a qualified nurse educator. Many AST subjects reported having to make multiple attempts to obtain an adequate sample, and several reported frustration in this regard.

Limitations and other considerations

Our sample size was designed to give our study sufficient power to detect a difference between the FT and AST groups as small as 0.5 units on the HbA1C percentage scale. A larger study would be required to conclusively rule out the possibility of a smaller change in mean HbA1C caused by the use of AST. The number of recorded hypoglycemic events in our study was small enough that we can neither prove nor exclude an effect of AST. A larger study is also needed to better characterize the risk for hypoglycemia or the failure to detect it.

In choosing a SMBG testing schedule we attempted to strike a balance between the unique requirements for the timing of tests for each individual with diabetes based on his or her insulin regimen and meal schedule, on one hand, and standardization between groups, on the other. We chose a standard regimen including two premeal tests and one postprandial test per day while allowing individual patients and providers to deviate from this schedule if they chose. It is possible that a study using an SMBG regimen more heavily weighted toward postprandial measurements would have different results regarding the impact of AST.

In designing the study, we also attempted to strike a balance between instructing the AST group to exclusively perform arm tests and giving them the flexibility to choose the method on a test-by-test basis. AST is generally suggested for use in clinical practice as an option for patients rather than an exclusive testing modality, but complete flexibility may have led to few actual arm tests. We therefore chose to ask subjects in the AST group to utilize arm testing “as much as possible,” but to use FT under the particular circumstances described. This was intended to maximize our ability to detect a difference between testing methods while maintaining the generalizability of our findings to real clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for the study was provided by Food and Drug Administration contract number 223-03-8720 to C.M.A. Some SMBG meters and test strips were provided by Lifescan.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Vincze G. Barner JC. Lopez D. Factors associated with adherence to self-monitoring of blood glucose among persons with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30:112–125. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fineberg SE. Bergenstal RM. Bernstein RM. Laffel LM. Schwartz SL. Use of an automated device for alternative site blood glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1217–1220. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tieszen KL. New JP. Alternate site blood glucose testing: do patients prefer it? Diabet Med. 2003;20:325–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellison JM. Stegman JM. Colner SL. Michael RH. Sharma MK. Ervin KR. Horwitz DL. Rapid changes in postprandial blood glucose produce concentration differences at finger, forearm, and thigh sampling sites. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:961–964. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peled N. Wong D. Gwalani S. Comparison of glucose levels in capillary blood samples obtained from a variety of body sites. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:35–44. doi: 10.1089/15209150252924067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki Y. Atsumi Y. Matusoka K. Alternative site testing increases compliance of SMBG (preliminary study of 3 years cohort trials) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;59:233–234. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(02)00193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedele D. Corsi A. Noacco C. Prisco F. Squatrito S. Torre E. Iafusco D. Errico MK. Toniato R. Nicolucci A. Franciosi M. De Berardis G. Neri L. Alternative site blood glucose testing: a multicenter study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2003;5:983–989. doi: 10.1089/152091503322641033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennion N. Christensen NK. McGarraugh G. Alternate site glucose testing: a crossover design. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:25–33. doi: 10.1089/15209150252924058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jungheim K. Koschinsky T. Risky delay of hypoglycemia detection by glucose monitoring at the arm. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1303–1306. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1303-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jungheim K. Koschinsky T. Glucose monitoring at the arm: risky delays of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia detection. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:956–960. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bina DM. Anderson RL. Johnson ML. Bergenstal RM. Kendall DM. Clinical impact of prandial state, exercise, and site preparation on the equivalence of alternative-site blood glucose testing. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:981–985. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DM. Weinert SE. Miller EE. A study of forearm versus finger stick glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:13–23. doi: 10.1089/15209150252924049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szuts EZ. Lock P. Malomo KJ. Anagnostopoulos A. Blood glucose concentrations of arm and finger during dynamic glucose conditions. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:3–11. doi: 10.1089/15209150252924030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucidarme N. Alberti C. Zaccaria I. Claude E. Tubiana-Rufi N. Alternate-site testing is reliable in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes except at the forearm for hypoglycemia detection. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:710–711. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cembrowski G. Alternative site testing: first do no harm. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:45–47. doi: 10.1089/15209150252924076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ginsberg B. The FDA reevaluates alternative site testing for blood glucose. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:347–349. doi: 10.1089/152091502760098492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Veciana M. Major CA. Morgan MA. Asrat T. Toohey JS. Lien JM. Evans AT. Postprandial versus preprandial blood glucose monitoring in women with gestational diabetes mellitus requiring insulin therapy. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1237–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511093331901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avignon A. Radauceanu A. Monnier L. Nonfasting plasma glucose is a better marker of diabetic control than fasting plasma glucose in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1822–1826. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.12.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monnier L. Lapinski H. Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA1C. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:881–885. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapp PE. Clemente KM. Phipps JC. Sternthal ES. Speckman JL. Ash AS. Freund KM. Apovian CM. Self-monitoring of blood glucose by finger-tip vs. alternate site sampling: effect on long term glycemic control [abstract]. Program and Abstracts of the Endocrine Society Annual Meeting; Jun 24–27;2006 ; Boston, MA. Chevy Chase, MD: Endocrine Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohlfing CL. Wiedmeyer HM. Little R. England JD. Tennill A. Goldstein DE. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA1c: analysis of glucose profiles and HbA1c in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:275–278. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]