Abstract

Proper vessel maturation, remodeling of endothelial junctions, and recruitment of perivascular cells is crucial for establishing and maintaining vessel functions. In proliferative retinopathies, hypoxia-induced angiogenesis is associated with disruption of the vascular barrier, edema, and vision loss. Therefore, identifying factors that regulate vascular maturation is critical to target pathological angiogenesis. Given the conflicting role of angiopoietin-like-4 (ANGPTL4) reported in the current literature using gain of function systems both in vitro and in vivo, the goal of this study was to characterize angiogenesis, focusing on perinatal retinal vascularization and pathological circumstances in angpl4-deficient mice. We report altered organization of endothelial junctions and pericyte coverage, both leading to impaired angiogenesis and increased vascular leakage that were eventually caught up, suggesting a delay in vessel maturation. In a model of oxygen-induced retinopathy, pathological neovascularization, which results from tissue hypoxia, was also strongly inhibited in angptl4-deficient mice. This study therefore shows that ANGPTL4 tunes endothelial cell junction organization and pericyte coverage and controls vascular permeability and angiogenesis, both during development and in pathological conditions.

Keywords: Cell Junctions, Development, Endothelium, Extracellular Matrix Proteins, Eye, Hypoxia, Angiogenesis, Angiopoietin

Introduction

The development of new blood vessels can be subdivided into two major phases: (1) sprouting angiogenesis per se, where endothelial cells differentiate into tip and stalk cells (migratory/environment sensing and proliferative endothelial cells, respectively), thereby leading to an immature vascular plexus, and (2) maturation, which involves recruitment of perivascular cells, deposition, and assembly of the basement membrane and establishment of tight and adherent junctions and transport systems (caveolae) in endothelial cells. Both phases can be studied simultaneously during development of the mouse retina between postnatal days 5 (P5)3 and 8 during which hypoxia is a major driving force of angiogenesis (1, 2). Although early events that induce and pattern new vessels have been studied intensively (3–5), events leading to vessel maturation crucial for establishment, maintenance, and control of vessel functions, such as blood flow and vascular permeability, have not yet been fully elucidated. Indeed, in pathological circumstances such as proliferative retinopathies (retinopathy of prematurity, diabetic retinopathy, and choroidal neovascularization), angiogenesis is associated with disruption of the vascular barrier, which leads to plasma leakage, subsequent edema, and vision loss.

Angiopoietins have been described as critical factors in vessel maturation. Angiopoietin-1 (ANG-1) promotes vessel maturation whereas angiopoietin-2 (ANG-2) antagonizes its effect on vessel stabilization (6). Recent reports have focused on retinopathies. Overexpression of ang-2 aggravates diabetic retinopathy (7), whereas ang-2 deficiency is associated with increased diameter and leakage of retinal capillaries (8). Among the angiopoietin family, ANGPTL4 is a secreted glycoprotein that is induced by hypoxia (9) and interacts with proteoglycans from the extracellular matrix (10, 11). ANGPTL4 does not bind to TIE-2 and is still an orphan ligand. In humans, ANGPTL4 is expressed in ischemic cardiovascular pathologies and in tumors (9, 12, 13). Both in vitro and in vivo gain of function experiments showed that ANGPTL4 regulates context-dependent angiogenesis and vascular permeability (14–16).

In this study, we sought to investigate the function of ANGPTL4 during both developmental and pathological retinal angiogenesis. We show here that ANGPTL4 is expressed in retinal endothelial cells in a developmentally regulated manner. Using angptl4-deficient mice, we here characterize a defect in sprouting and branching during developmental angiogenesis, a delay in the maturation of the retinal vasculature as shown by alterations in endothelial cell junctions and defects in pericyte coverage, and increased vascular leakage. Furthermore, pathological neovascularization, which results from tissue hypoxia, is impaired in angptl4-deficient mice in a model of retinopathy of prematurity. Altogether, these results provide genetic evidence that loss of ANGPTL4 impairs sprouting angiogenesis resulting from tissue hypoxia, both in developmental and in pathological conditions, and delays maturation of blood vessels and acquisition of vascular barrier properties.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

The experiments were performed in accordance with the official regulations set forth by the French Ministry of Agriculture and the European Union Council Directives (86/609/EEC). This study conforms to the standards of INSERM (the French National Institute of Health) regarding the care and use of laboratory animals.

Genotyping of angptl4LacZ/LacZ Mice

Genotype was determined by PCR of tail DNA under the following conditions: Denaturation at 94 °C for 0.5 min, annealing at 56 °C for 0.75 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1.15 min, 30 cycles. The following primers pairs were used: angptl4, 5′-AAGGAGCAAAGGGTGCGAGAGAGTTG-3′ and 5′-TTGGGGAAACATTGGTGGC-3′; and LacZ, 5′-CGAAAACCCAAACTGTGGAG-3′ and 5′-TTCATTCCCCAGCGACCAGATG-3′.

Neonatal Retinal Vascular Network Analysis

P6 and P7 pups were sacrificed and the eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Retinas were dissected, and immunostaining was performed as described previously (17). For LacZ staining, retinas where washed three times in PBS and incubated at 37 °C in a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) solution. For staining, retinas were fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in blocking buffer (PBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.1% Tween 20). After three washes of 20 min in Pblec buffer (PBS, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm MnCl2, 1 mm CaCl2), retinas were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with primary antibodies and/or isolectin B4 (IB4) in Pblec buffer. After three PBS washes, retinas were incubated with fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies in incubation buffer (PBS, 0.25% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20). Retinal flat mounts were then prepared in fluorescent mounting medium (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) and visualized using a Leica (Deerfield, IL) TCS SP5 microscope using a ×10/0.3 numerical aperture, ×20/0.7 numerical aperture, ×40/1.25 numerical aperture, or ×63/1.4 numerical aperture objective. For Ve-cadherin (VE-CAD) immunostaining, mice were perfused with 1% paraformaldehyde, and retinas were processed using Ca2+-Mg2+ PBS (CaCl2 1 mm, MgCl2 1 mm).

Retinas were immunostained using biotinylated IB4 (1:50, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), anti-chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (NG2, 1:40, Chemicon Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:75, DAKO), anti-caveolin 1 (CAV-1, BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1, 1:100, Invitrogen), and anti-VE-CAD (BV-13, gift from E. Dejana, Institute of Molecular Oncology Foundation Milano). The corresponding streptavidin conjugate and secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen).

Immunoblotting Analyses

P7 pups were sacrificed, the eyes were enucleated, and retinas were dissected. Proteins were extracted on ice in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% deoxycholate, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm NaF, 2.5 mm Na pyrophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, and a mixture of protease inhibitors (Calbiochem). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting on a nitrocellulose membrane. Anti-CAV-1, anti-actin (Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, UK) and appropriate phosphatase alkaline-coupled secondary antibodies were used. The signal was revealed by Attophos chemiluminescence (Promega) and band intensity was quantified by Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad).

Real-time Quantitative PCR Analysis

P7 pups were sacrificed, the eyes were enucleated, and retinas were dissected. Total RNA was isolated by extraction using a commercial kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany, Nucleospin RNA II). Reverse transcription, real-time quantitative PCR (in triplicate) and analysis were performed as described previously (18). Vegfa, vegfr2, and Cav-1 genes were detected using QuantiTect primer assays (Qiagen). The mRNA expression level was normalized to the housekeeping gene encoding gapdh. Fold changes were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle method.

Quantification of Vascular Phenotype

Images of whole mount retinas were acquired on a Leica DM LB microscope using a ×20/0.4 NA objective and captured using a QImaging Fast1394 camera through Qcapture software version 2.98.2 (Quantitative Imaging Corp., Surrey, British Columbia, Canada). The number of branch points per field was quantified with the Biologic CMM analyzer software (Centre de Morphologie Mathematiques-ARMINES, France) (19). Vessel diameter and filopodia bursts were counted manually. Using ImageJ software, images were filtered and converted to binary images. The total vessel area was assessed by counting the number of white versus black pixels in the binary images. Quantifications were performed on six to eight images per retina (n = 8 per group).

Neonatal Retinal Miles Assay

Evans Blue (10 mg/ml) was injected into the tail vein of P7 angptl4LacZ/LacZ and angptl4+/LacZ control mice. Thirty minutes later, mice were sacrificed, and an intracardiac perfusion was performed with citrate buffer (pH 4) to remove intravenous Evans Blue. Eyes were enucleated and retinas dissected and then weighed. Evans Blue was then eluted from retinas in 0.5 ml of formamide for 18 h at 70 °C. After centrifugation, the absorbance was measured at 620 nm using a spectrophotometer (Biomate 3, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Extravated Evans blue (ng) was determined from a standard curve and normalized to retinal weight (g).

Extravasation of FITC Beads

FITC beads (Duke Scientific Corp., Palo Alto, CA) were diluted 1:10 in physiological serum, and 20 μl were injected into the tail vein in anesthetized pups. The vasculature was then perfused with 5 ml of 1% paraformaldehyde. Retina whole mounts were imaged on a Leica TCS SP5 microscope using a ×63/1.4 NA oil immersion objective. An increment of 0.117 μm between each section was used. Deconvolution of the stacks of pictures was made using the Amira deconvolution module. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the different structures was obtained using the labelvoxel and surfacegen modules in the Amira 5.2.1 software (Visage Imaging GmbH).

Oxygen-induced Retinopathy

P7 pups, along with nursing mothers, were placed in 75% oxygen for 5 days and then returned to room air. The oxygen concentration was maintained by a Pro-OX oxygen controller (BioSpherix, NY). Pups were sacrificed at different time points: P12 and P17. Eyes were enucleated and fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunostaining was performed as described above. Retinal flat mounts were generated, and confocal images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP5 microscope with a ×20/0.7 NA oil immersion objective. Photomerge was performed with Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). The vaso-obliterated area was quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical Analysis

Mann-Whitney tests were used to assess the statistical differences between measurements (GraphPad Prism 4, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Histograms represent mean ± S.E. and ns, p > 0.05. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001.

RESULTS

ANGPTL4 Modulates Sprouting, Branching, and Maturation of the Retinal Vascular Plexus

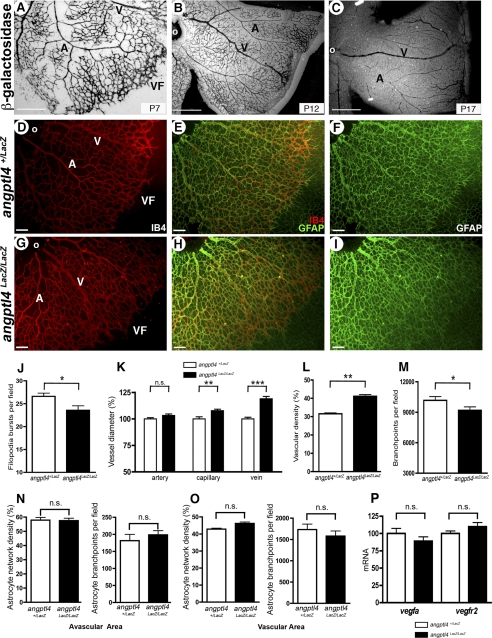

We first sought to investigate the function of ANGPTL4 during developmental angiogenesis using a genetic mouse model in which the angptl4 gene was replaced by a knockin LacZ cassette (20), thereby generating angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice. Some lethality was observed during development, but surviving angptl4LacZ/LacZ neonates were obtained at approximately 6% (compared with the 25% expected frequency, supplemental Fig. 1) that were viable and fertile and did not exhibit obvious defects. β-gal staining in angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice on whole mount retinas showed expression in endothelial cells in the capillary plexus as well as in veins and arteries of the developing retina at critical time points during development, i.e. P7, P12, and P17 (Fig. 1, A–C). We then addressed whether ANGPTL4 could play a role during development of the retinal vasculature. We compared IB4-stained P6 retinal flat whole mounts from angptl4LacZ/LacZ and angptl4+/LacZ pups (Fig. 1, D and G) used as controls, as they did not exhibit any difference with wild-type mice (data not shown). First, we focused our attention on sprouting at the vascular front. The mean number of filopodia bursts in the vascular front was quantified as described above (supplemental Fig. 2B) and was found to be significantly decreased in angptl4LacZ/LacZ pups (Fig. 1J). Expansion of the retinal blood vessel network was similar in both genotypes (data not shown). Using confocal images of IB4-stained retinas, we then manually quantified artery, vein, and capillary diameters in retinas of angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice versus control mice. Veins and capillaries from angptl4LacZ/LacZ were larger (15 and 8%, respectively) than their angptl4+/LacZ counterparts (Fig. 1K), whereas artery thickness was similar. Also, an increase in vascular density (that corresponds to the ratio between IB4-positive (IB4+) area and total retina area) and a decrease in number of branch points (quantified as described in the previous section and in supplemental Fig. 2B), were quantified in retinas from angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice (Fig. 1, L and M, respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Defective developmental angiogenesis in angptl4-deficient pups. A–C, LacZ staining shows expression of angptl4 in endothelial cells at P7 (A), P12 (B), and P17 (C) during developmental angiogenesis of the retina. Scale bar = 500 μm. D–F and G–I, IB4 (red) and GFAP (green) staining allow quantification of the vascular and astrocytic networks, respectively. A, artery; V, vein; VF, vascular front; o, optic nerve. Scale bar = 100 μm. Quantification of filopodia bursts/field of view (J); of artery, capillary and vein diameter (K); of vascular density (% of IB4 positive surface/total field area) (L); of vessel branch points/field of view (M); of astrocyte network density (left panel) and of astrocyte branch points/field of view (right panel) in the avascular (N) and vascular (O) area in angptl4+/LacZ and angptl4LacZ/LacZ P6 retinas (n = 8 per group). Shown is quantification by real-time quantitative PCR of vegfa and vegfr2 mRNAs (P) and in angptl4+/LacZ and angptl4LacZ/LacZ P7 retinas (n = 3 per group). GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein. ns, non significant.

The astrocytic network is known to guide vascular expansion in the retina (21). We therefore next examined both its network density and branch points in avascular and vascular areas (Fig. 1, N and O, respectively) using anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody in both angptl4LacZ/LacZ and angptl4+/LacZ pups (Fig. 1, E, F, H, and I). No difference was observed both in the vascular and avascular areas between both genotypes. Furthermore, no difference was observed in retina vegfa mRNA expression (Fig. 1P) between angptl4LacZ/LacZ and angptl4+/LacZ retinas, suggesting that astrocytes in angptl4-deficient mice also function normally by producing equal levels of vegfa mRNA. As a control, we also show that vegfr2 mRNA expression levels in retinal endothelial cells are not differentially expressed between both genotypes. Altogether, these results suggest that astrocytes are not likely to be involved in regulating the defects of the developing vascular network in angptl4LacZ/LacZ pups.

Altogether, these data show that sprouting and branching as well as maturation of blood vessels are affected during developmental angiogenesis of the retinas in angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice.

Endothelial Cell Differentiation Markers Are Altered in the Microvascular Plexus of angptl4-deficient Mice

We then further examined the developing vascular network of the retina, thereby allowing to distinguish three distinct regions: Area 1, mature vascular plexus, close to the optic nerve, with differentiated veins and arteries (α-smooth muscle actin positive cell coverage) and thin capillaries; area 2, immature vascular plexus undergoing remodeling, characterized by capillaries with larger diameters; and finally, area 3, the vascular front, where tip and stalk cells are located (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B).

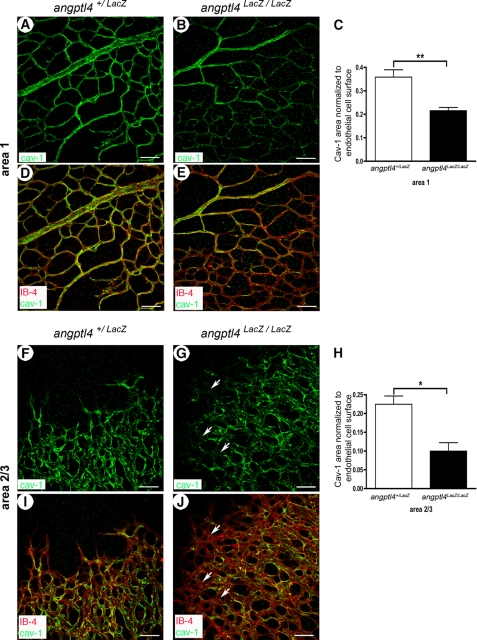

We used immunostaining of CAV-1, an important regulator of blood vessel maturation (22), to distinguish the mature network (area 1) from the outgrowing, immature vascular plexus (areas 2/3) in P6 control retinas (supplemental Fig. 2, C–F). To avoid any bias in the analysis of CAV-1 staining because of differences in vessel density between vascular areas or between mouse strains, we normalized the CAV-1+ area to the total vessel area (IB4+). Quantification of the ratio of CAV-1+ surface and endothelial cell surface (IB4 + vessels) was performed in both areas (supplemental Fig. 2, E and F), showing a 37.4% decrease in immature areas 2/3 when compared with mature area 1. This ratio was then quantified in P6 retinas from angptl4LacZ/LacZ and control mice (Fig. 2, A–J), thereby revealing a decrease in both areas of angptl4LacZ/LacZ pups (−40% and −56% in areas 1 and 2/3, respectively) (Fig. 2, C and H). To investigate whether these findings could result from a different basal expression level, we performed real-time quantitative PCR and Western blot analyses. No differences were observed in both mRNA and proteins levels of CAV-1 from angptl4LacZ/LacZ and angptl4+/LacZ P7 retinal extracts (supplemental Fig. 3, A and B). These results therefore suggest an overall defect in vessel maturation in the retina of angptl4-deficient pups, which is more pronounced in the yet immature vascular plexus.

FIGURE 2.

Perturbation of CAV-1 staining in angptl4-deficient pups. A–E, reduced CAV-1 expression in area 1 of angptl4-deficient mice. CAV-1 staining (green) is homogeneous in area 1 of angptl4+/LacZ vasculature (A and D) but weaker and discontinuous in capillaries from area 1 of angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas (B and E). Scale bar = 50 μm. IB4 is shown in red (D and E). C, shown is the ratio of CAV-1-positive vessels to endothelial cell surface (IB4+ vessels). p < 0.01. F–J, reduced CAV-1 expression in areas 2/3 of angptl4-deficient mice. CAV-1 staining (green) is discontinuous in angptl4+/LacZ vasculature (F and I) but weaker in capillaries from area 2 and rarely present in area 3 (white arrows) of angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas (G and J). p < 0.01. IB4 is shown in red. Scale bar = 50 μm. H, shown is the ratio of CAV-1-positive vessels to endothelial cell surface (IB4-positive vessels) (n = 4 per group).

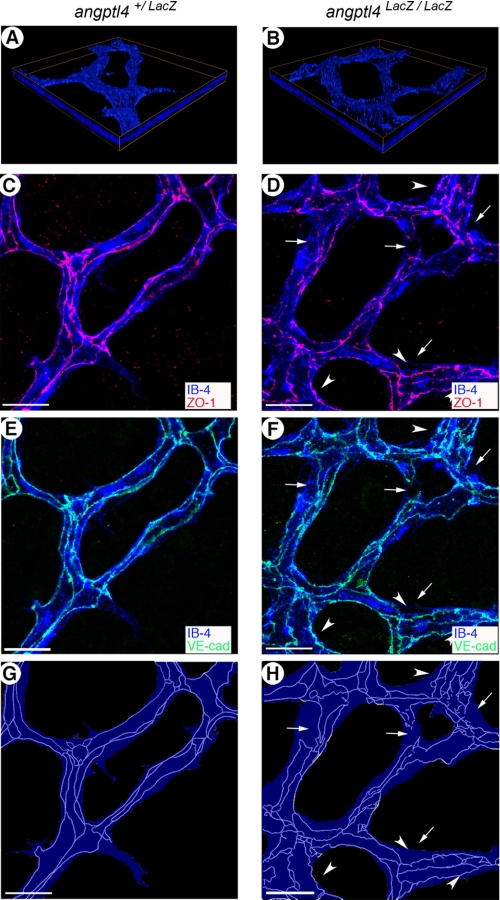

We next investigated the distribution of endothelial cell junction molecules, as their organization is also associated with vessel maturation. Distribution of VE-CAD and ZO-1, principal components of adherent and tight junctions respectively, was studied in P7 retinas of angptl4LacZ/LacZ and control mice. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, we analyzed VE-CAD and ZO-1 stainings at different depths within the retina covering the full thickness of the vessel network using confocal microscopy. Although intercellular junctions of the endothelium had continuous and elaborate junctions in control mice (Fig. 3, C and E), VE-CAD and ZO-1 were found to be more heterogeneously distributed in mutant pups (Fig. 3, D and F). Using a schematic representation of interendothelial cell junctions (Fig. 3, G and H), which allowed better appreciation of organization defects, endothelial junctions appeared disorganized and tortuous in angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinal vessels (Fig. 3, D, F and H). In the mature vascular plexus (area 1), endothelial cell tight junctions were continuous and properly organized in angptl4+/LacZ pups (supplemental Fig. 4, A and C), whereas they remained loosely organized in angptl4 LacZ/LacZ (supplemental Fig. 4, B and D). In contrast, in the vascular front (area 3), endothelial cell tight junctions showed a similar degree of immaturity in both groups (supplemental Fig. 4, E and H).

FIGURE 3.

Perturbation of endothelial junction integrity in angptl4-deficient pups. A and B, focal plane by three-dimensional reconstruction of IB4 (blue) staining in angptl4+/LacZ and angptl4LacZ/LacZ P7 retinas. ZO-1 (red) (C and D) and VE-CAD (green) (E and F) staining reveals discontinuous endothelial junctions in area 2 of angptl4-deficient vasculature (the arrows point to discontinuous junctions at branch points and the arrowheads indicate tortuous-like junctions) (D and F). Scale bar = 15 μm. G and H, schematic representation of the endothelial surface of IB4 staining (blue) and endothelial junctions of VE-CAD and ZO-1 staining (light blue tracing). Endothelial junctions are poorly developed in angptl4LacZ/LacZ capillaries (H) compared with mature junctions in control retinas (G).

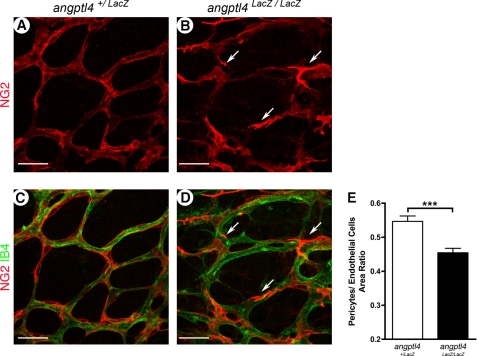

Pericyte Coverage Is Delayed during Maturation of the Microvascular Plexus in angptl4-deficient Mice

We recently published that ANGPTL4 binds to extracellular matrix components (11) such as heparan sulfates, which are known to interact with PDGF through its retention domain, this being critical for pericyte recruitment and attachment to endothelial cells (23, 24). We then sought to investigate whether ANGPTL4 modulates pericyte recruitment and spreading during vessel maturation of newly formed vessels. At P7, retinas were double-stained with the pericyte marker NG2 and IB4 as an endothelial marker. Pericyte recruitment was not perturbed because areas of pericyte-free capillaries were never observed in angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas. Nevertheless, in contrast to control mice (Fig. 4, A and C), pericytes failed to spread and flatten on endothelial cells, showing a prominent cellular body and well marked filopodia in areas 2/3 of angptl4 LacZ/LacZ retinas (Fig. 4, B and D). Pericyte coverage was then determined as the surface ratio of NG2+ pericytes normalized to IB4+ endothelial cells. This ratio was significantly diminished in angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice compared with control mice (19% decrease, Fig. 4E). In the vascular plexus close to the optic nerve, which had already undergone remodeling (area 1), pericyte coverage was not affected in angptl4LacZ/LacZ pups at P7 (supplemental Fig. 5). In addition, pericyte coverage of the superficial layer was unaffected at P21 (data not shown). Thus, angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice exhibit a delay in pericyte spreading on newly formed capillaries, which is eventually caught up at later stages of the maturation process.

FIGURE 4.

Defects in pericyte coverage in developmental angptl4LacZ/LacZretinas. A–E, delay of pericyte coverage in area 2 of P7 angptl4 LacZ/LacZ retinas. Representative images of P7 angptl4+/LacZ (A and C) and angptl4LacZ/LacZ (B and D) retinas stained with IB4 (red) and NG2 (green) (A–D). The arrows point to abnormal pericytes (B and D) on angptl4 LacZ/LacZ capillaries. Scale bar = 25 μm. E, shown is the ratio of pericytes (NG2+ area) to endothelial cell surface (IB4+ vessels), n = 6 per group. p < 0.005.

ANGPTL4 Controls the Permeability of the Retinal Vascular Plexus

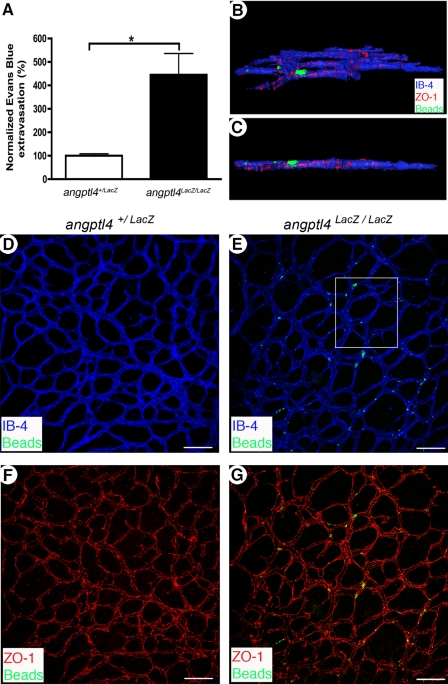

Having shown that angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas have a delay in vascular network maturation during postnatal development, we then analyzed whether vascular permeability might be affected using two complementary methods. We first used a modified Miles assay to quantify global vascular leakage in P7 retinas. Evans Blue leakage was more prominent from angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinal vessels (Fig. 5A) compared with controls (3.5-fold increase). Moreover, we showed that FITC-coupled microspheres did not extravasate from control angptl4+/LacZ P7 pups (Fig. 5, D and F), whereas they did from angptl4LacZ/LacZ vessels (Fig. 5, E and G). As expected, deconvolution of confocal Z-stacks and three-dimensional reconstruction analyses confirmed bona fide extravasation of FITC-coupled microspheres from immature vessels of areas 1 and 2 in angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice (Fig. 5, B and C).

FIGURE 5.

Increased vessel permeability in angptl4-deficient pups. A, leakage of Evans Blue in P7 angptl4+/LacZ and angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas. Values are expressed as % of the control (angptl4+/LacZ) value, (angptl4+/LacZ, n = 4; angptl4LacZ/LacZ, n = 5). B and G, confocal images of whole mount P7 angptl4+/LacZ and angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas stained with IB4 (blue) and ZO-1 (red). Prior to sacrifice, fluorescent 100 nm microspheres were injected intravenously and flushed from circulation 15 min afterwards. B and C, deconvolution and three-dimensional reconstruction of the boxed region in E. Extravasated microspheres are trapped around tight junctions with a large part outside of the vessel (ZO-1, red). Field dimensions are 200 × 220 × 7 μm. E and G, extravasated microspheres (green) were only observed in angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 6 per group. p < 0.05.

ANGPTL4 Protects Vessels from Oxygen-induced Obliteration

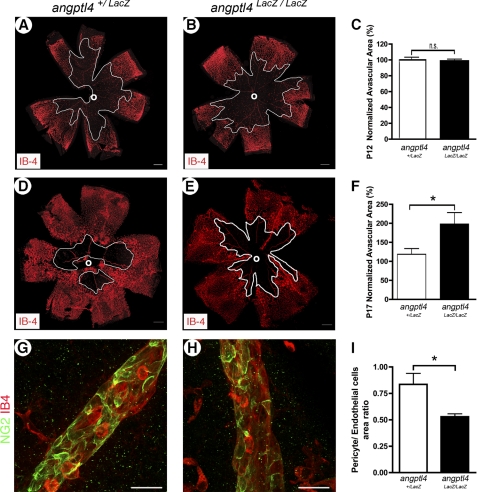

Because pathological retinal neovascularization is typically the result of local tissue hypoxia, we also investigated the role of ANGPTL4 in the modulation of revascularization during oxygen-induced retinopathy that mimics ischemia-induced angiogenesis observed in retinopathy of prematurity. Angptl4 expression was first investigated using β-gal staining of angptl4LacZ/LacZ whole mount retinas, showing expression in endothelial cells in the capillary plexus and in the vascular tufts as well as in veins and arteries at critical time points during oxygen-induced retinopathy, i.e. P12 and P17 (supplemental Fig. 6, A and B). Oxygen-induced retinal vessel loss (from P7 to P12), was unaffected at P12 in angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice when compared with control mice (Figs. 6, A–C). In contrast, neovascularization was strongly altered because an increased vaso-obliterated area was observed in angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice at P17, when neovascularization should be maximal (60% increase in angptl4LacZ/LacZ when compared with controls, Fig. 6, D–F). In addition, a significant decrease of pericyte coverage was measured at P17 in angptl4LacZ/LacZ veins, which are the major site of sprouting angiogenesis (32.5% decrease, Fig. 6, G–I). Altogether, these data show that hypoxia-driven pathological neovascularization was compromised in the retina of angptl4LacZ/LacZ mice.

FIGURE 6.

Loss of angptl4 inhibits neovascularization during oxygen-induced retinopathy. A–C, hyperoxia-induced vaso-obliteration is unaffected in angptl4-deficient mice. A and B, images of whole mount P12 angptl4+/LacZ and angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas stained with IB4. The avascular area around the optic nerve (o) is outlined in white. Scale bars = 300 μm. C, values are expressed as % of the control (angptl4+/LacZ) value (angptl4+/LacZ, n = 7; angptl4LacZ/LacZ, n = 11). D–I, neovascularisation at P17 is reduced in angptl4-deficient mice. Images of whole-mount P17 angptl4+/LacZ and angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas stained with IB4 (D–E). The avascular area is outlined in white. Scale bars represent 300 μm. F, values are expressed as % of the control (angptl4+/LacZ) value, n = 6 per group. G–I, defective pericyte coverage of veins in P17 angptl4LacZ/LacZ retinas after oxygen-induced retinopathy. Representative images of OIR P17 angptl4+/LacZ (G) and angptl4LacZ/LacZ (H) retinas stained with IB4 (red) and NG2 (green) (G–H). Scale bar represents 50 μm. Ratio of NG2-positive vessels to IB4-positive vessels (I), n = 3 per group. p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study reports the first genetic evidence of the role of ANGPTL4 on retina angiogenesis during development as well as in pathological conditions. The principal findings of this study are as follows: angptl4 is expressed in retinal endothelial cells during development and oxygen-induced retinopathy. Loss of ANGPTL4 inhibits pathological angiogenesis in ischemic ocular diseases. During development, we observed altered expression of endothelial cell maturation markers such as caveolin-1 and junction molecules, diminished pericyte coverage, and increased vascular permeability, which altogether characterize a delayed vascular maturation in angptl4-deficient pups. These defects were eventually caught up at later stages, suggesting that ANGPTL4 acts during a critical developmental period. Indeed, expression of ANGPTL4 is dynamically induced by hypoxia, whose role in the regulation of retina vascular development (25) and neovascularization in pathological conditions is well established in ocular diseases (26, 27).

The present study provides new insights into the characterization of vessel maturation and acquisition of vascular barrier features (such as control of vascular permeability). Indeed, we here describe different areas, according to maturation state of retinal blood vessels, through the study of their morphology and the analysis of endothelial cell maturation markers: Area 1, close to the optic nerve is characterized by a clear capillary-free zone, fully differentiated arteries, and thin capillaries that display continuous endothelial junctions; area 2, in which vessel remodeling and pruning are ongoing processes and where large capillaries display both locally discontinuous endothelial junctions and coverage of stabilizing pericytes; and finally area 3, where tip and stalk cells are present and where both pericyte coverage and endothelial junctions are still immature. At P7, the presence of these immature junctions suggests that vascular maturation is not yet fully established throughout the retina. However, no vascular leakage of FITC-labeled microspheres was detected at this stage in control pups, implying that control of vascular permeability was established at earlier steps. However, unlike in control animals, vessel leakage was observed in angptl4-deficient mice at P7, allowing extravasation of both Evans Blue and 100 nm fluorescent microspheres. The latter allowed localization of vascular permeability in the developing retina that correlated with the increased proportion of immature vessels observed in angptl4-deficient pups at P7.

To provide the cellular basis of this loss of vascular barrier properties in angptl4-deficient mice, we focused our attention on three different markers of complementary steps of vessel maturation: 1) caveolae/CAV-1, 2) endothelial cell junction organization, and 3) pericyte recruitment and/or spreading. Caveolae are uncoated vesicles enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids (28), responsible for transcellular permeability in endothelial cells (29), and vascular permeability is highly increased in caveolin-1-deficient mice (30, 31). In control mice, we here report that its distribution is not homogeneous in endothelial cells from the immature vascular network, thereby allowing to delineate mature from immature vessels during development through caveolin-1 immunostaining. In angptl4-deficient pups, the ratio of caveolin-1+ area normalized to endothelial surface was diminished, thereby characterizing a larger yet immature network (area 2/3) compared with control retinas. However, these differences in CAV-1 distribution are not underlined by differences in gene or protein expression levels between angptl4LacZ/LacZ and control pups. These findings suggest that the subcellular localization of CAV-1 is also an indicator of vessel maturation.

Adherent and tight junctions are also critical regulators of the vascular barrier properties (32) and restrict paracellular vascular permeability in the retinal vasculature. In addition, hypoxia has been reported to alter tight junction components and to subsequently increase vascular permeability, although the mechanism was not fully understood (33). Capillaries from angptl4-deficient mice display an increased proportion of immature junctions characterized by a loss of organization of ZO-1 and VE-CAD in area 2. Importantly, we could also observe that some immature junctions persist in area 1 in angptl4-deficient mice. Previous data suggested that recombinant ANGPTL4 alters the distribution of ZO-1 in the human endothelial cell monolayer (16). In contrast, our results show that a loss of ANGPTL4 delays maturation of endothelial cell junctions, eventually leading to abnormal vascular leakage. These results are in line with previous studies showing that ANGPTL4 inhibits vascular permeability (14, 15). Therefore, our data suggest that although hypoxia triggers angiogenesis and increased vascular leakage, it may also launch a feedback loop on retinal vascular permeability that limits plasma leakage and endothelial cell disorganization through expression of ANGPTL4.

During developmental angiogenesis and in the oxygen-induced retinopathy, we also quantified diminished pericyte coverage in both capillaries and veins. This phenotype was neither associated with vascular regression nor excessive angiogenesis, as reported when pericyte dropout is involved (34), but with a delay in vessel maturation during development and an inhibition of angiogenesis in oxygen-induced retinopathy. These observations are consistent with previous reports that have shown that compromised interaction of pericyte and endothelial cells in retinal blood vessels are associated with defective angiogenesis during development, such as in endothelium-specific Pdgfb knockout mice (35) and in response to ANG-2 in a model of diabetic retinopathy (36). In addition, our results suggest that ANGPTL4 is not involved in pericyte recruitment per se but rather that pericytes failed to spread on angptl4-deficient endothelial cell tubes. Whether these changes in pericyte morphology are a cause or a consequence of defects in vascular maturation remains to be elucidated. The magnitude of these morphologic changes rather suggests a secondary effect to the endothelial defects, where angptl4 expression is detected.

These results show that ANGPTL4 regulates retinal neovascularization as ANG-2 but prevents vascular permeability (14, 15), as ANG-1 (37). Although ANGPTL4 does not bind to TIE-2, these findings raise the hypothesis that ANGPTL4 may participate in the normalization of retinal vessels. The concept of vessel normalization was first established in tumor angiogenesis (38, 39) in which HIF-2α has recently been shown to regulate proper maturation and function of newly formed vessels (40). In such a hypoxic environment, immature vessels are permeable and lack stabilizing pericytes, leading to edema and defects in nutritive flow (41). The goal of anti-angiogenic strategies is therefore to inhibit plasma leakage, increase pericyte coverage, and reduce vessel diameter and tortuosity, thereby restoring optimal blood flow (42). In vascular ocular diseases, normalization of excessive angiogenesis might constitute a relevant therapeutic approach, as reestablishment of a proper vascular barrier would also reduce plasma leakage and edema. Indeed, preclinical studies report the beneficial effect of blocking VEGFA signaling in diabetic retinopathy (43) and in “wet” age-related macular degeneration (44), and VEGFA blocking antibodies are prescribed to patients suffering from wet age-related macular degeneration (45).

Taken together, our results suggest that ANGPTL4 controls hypoxia-driven angiogenesis and vessel maturation in the retina and might therefore represent a double-edged therapeutic sword in treatments aimed at both reducing uncontrolled pathological angiogenesis and reinforcing the vascular barrier during ocular vascular pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Catarina Freitas and Raquel del Toro for valuable help.

This work was supported in part by Institut de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grant ANR-06-JCJC-0160, the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, Fondation de France Grant R09045JJ, and an Attaché Temporaire d'Enseignement et de Recherche position from the Collège de France (to E. G. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–6.

- P5

- postnatal day 5

- IB4

- isolectin B4

- VE-CAD

- Ve-cadherin

- CAV-1

- caveolin 1

- ZO-1

- zonula occludens 1

- ANGPTL4

- angiopoietin-like-4.

REFERENCES

- 1. Holderfield M. T., Hughes C. C. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 637–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Germain S., Monnot C., Muller L., Eichmann A. (2010) Curr. Opin. Hematol. 17, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams R. H., Alitalo K. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 464–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phng L. K., Gerhardt H. (2009) Dev. Cell 16, 196–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iruela-Arispe M. L., Davis G. E. (2009) Dev. Cell 16, 222–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maisonpierre P. C., Suri C., Jones P. F., Bartunkova S., Wiegand S. J., Radziejewski C., Compton D., McClain J., Aldrich T. H., Papadopoulos N., Daly T. J., Davis S., Sato T. N., Yancopoulos G. D. (1997) Science 277, 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pfister F., Wang Y., Schreiter K., vom Hagen F., Altvater K., Hoffmann S., Deutsch U., Hammes H. P., Feng Y. (2010) Acta Diabetol. 47, 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feng Y., Wang Y., Pfister F., Hillebrands J. L., Deutsch U., Hammes H. P. (2009) Cell Physiol. Biochem. 23, 277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Le Jan S., Amy C., Cazes A., Monnot C., Lamandé N., Favier J., Philippe J., Sibony M., Gasc J. M., Corvol P., Germain S. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 162, 1521–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cazes A., Galaup A., Chomel C., Bignon M., Bréchot N., Le Jan S., Weber H., Corvol P., Muller L., Germain S., Monnot C. (2006) Circ. Res. 99, 1207–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chomel C., Cazes A., Faye C., Bignon M., Gomez E., Ardidie-Robouant C., Barret A., Ricard-Blum S., Muller L., Germain S., Monnot C. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 940–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le Jan S., Le Meur N., Cazes A., Philippe J., Le Cunff M., Léger J., Corvol P., Germain S. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 3395–3400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Verine J., Lehmann-Che J., Soliman H., Feugeas J. P., Vidal J. S., Mongiat-Artus P., Belhadj S., Philippe J., Lesage M., Wittmer E., Chanel S., Couvelard A., Ferlicot S., Rioux-Leclercq N., Vignaud J. M., Janin A., Germain S. (2010) PLoS ONE 5, e10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ito Y., Oike Y., Yasunaga K., Hamada K., Miyata K., Matsumoto S., Sugano S., Tanihara H., Masuho Y., Suda T. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 6651–6657 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galaup A., Cazes A., Le Jan S., Philippe J., Connault E., Le Coz E., Mekid H., Mir L. M., Opolon P., Corvol P., Monnot C., Germain S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18721–18726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Padua D., Zhang X. H., Wang Q., Nadal C., Gerald W. L., Gomis R. R., Massagué J. (2008) Cell 133, 66–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gerhardt H., Golding M., Fruttiger M., Ruhrberg C., Lundkvist A., Abramsson A., Jeltsch M., Mitchell C., Alitalo K., Shima D., Betsholtz C. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161, 1163–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu Y., Yuan L., Mak J., Pardanaud L., Caunt M., Kasman I., Larrivée B., Del Toro R., Suchting S., Medvinsky A., Silva J., Yang J., Thomas J. L., Koch A. W., Alitalo K., Eichmann A., Bagri A. (2010) J. Cell Biol. 188, 115–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones E. A., Yuan L., Breant C., Watts R. J., Eichmann A. (2008) Development 135, 2479–2488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Valenzuela D. M., Murphy A. J., Frendewey D., Gale N. W., Economides A. N., Auerbach W., Poueymirou W. T., Adams N. C., Rojas J., Yasenchak J., Chernomorsky R., Boucher M., Elsasser A. L., Esau L., Zheng J., Griffiths J. A., Wang X., Su H., Xue Y., Dominguez M. G., Noguera I., Torres R., Macdonald L. E., Stewart A. F., DeChiara T. M., Yancopoulos G. D. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 652–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fruttiger M. (2002) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 522–527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frank P. G., Woodman S. E., Park D. S., Lisanti M. P. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 1161–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindblom P., Gerhardt H., Liebner S., Abramsson A., Enge M., Hellstrom M., Backstrom G., Fredriksson S., Landegren U., Nystrom H. C., Bergstrom G., Dejana E., Ostman A., Lindahl P., Betsholtz C. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1835–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abramsson A., Lindblom P., Betsholtz C. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1142–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kubota Y., Suda T. (2009) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 19, 38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pe'er J., Shweiki D., Itin A., Hemo I., Gnessin H., Keshet E. (1995) Lab. Invest. 72, 638–645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arjamaa O., Nikinmaa M. (2006) Exp. Eye Res. 83, 473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simons K., Toomre D. (2000) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1, 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Razani B., Engelman J. A., Wang X. B., Schubert W., Zhang X. L., Marks C. B., Macaluso F., Russell R. G., Li M., Pestell R. G., Di Vizio D., Hou H., Jr., Kneitz B., Lagaud G., Christ G. J., Edelmann W., Lisanti M. P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38121–38138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murata T., Lin M. I., Huang Y., Yu J., Bauer P. M., Giordano F. J., Sessa W. C. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 2373–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dewever J., Frérart F., Bouzin C., Baudelet C., Ansiaux R., Sonveaux P., Gallez B., Dessy C., Feron O. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 171, 1619–1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sagaties M. J., Raviola G., Schaeffer S., Miller C. (1987) Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 28, 2000–2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Witt K. A., Mark K. S., Hom S., Davis T. P. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 285, H2820–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Augustin H. G., Koh G. Y., Thurston G., Alitalo K. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 165–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bjarnegård M., Enge M., Norlin J., Gustafsdottir S., Fredriksson S., Abramsson A., Takemoto M., Gustafsson E., Fässler R., Betsholtz C. (2004) Development 131, 1847–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hammes H. P., Lin J., Wagner P., Feng Y., Vom Hagen F., Krzizok T., Renner O., Breier G., Brownlee M., Deutsch U. (2004) Diabetes 53, 1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thurston G., Rudge J. S., Ioffe E., Zhou H., Ross L., Croll S. D., Glazer N., Holash J., McDonald D. M., Yancopoulos G. D. (2000) Nat. Med. 6, 460–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jain R. K. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heath V. L., Bicknell R. (2009) Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 6, 395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Skuli N., Liu L., Runge A., Wang T., Yuan L., Patel S., Iruela-Arispe L., Simon M. C., Keith B. (2009) Blood 114, 469–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walshe T. E., D'Amore P. A. (2008) Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3, 615–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Greenberg J. I., Cheresh D. A. (2009) Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 9, 1347–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nakajima M., Cooney M. J., Tu A. H., Chang K. Y., Cao J., Ando A., An G. J., Melia M., de Juan E., Jr. (2001) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 2110–2114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Miki K., Miki A., Matsuoka M., Muramatsu D., Hackett S. F., Campochiaro P. A. (2009) Ophthalmology 116, 1748–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bressler N. M. (2009) Ophthalmology 116, S15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.