Background: N,N′-Dinitrosopiperazine (DNP) is associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) metastasis, but its mechanism is not clear.

Results: DNP induces ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567 by activating Rho kinase and PKC and increases motility and invasion of NPC cells.

Conclusion: DNP is involved in NPC metastasis through regulation of ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567.

Significance: DNP-mediated ezrin phosphorylation is a novel mechanism for NPC metastasis.

Keywords: Carcinogenesis, Chemical Modification, Protein Kinases, Protein Phosphorylation, Rho, Tumor Metastases, Dinitrosopiperazine, Ezrin, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Abstract

N,N′-Dinitrosopiperazine (DNP) is a carcinogen for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), which shows organ specificity to nasopharyngeal epithelium. Herein, we demonstrate that DNP induces fiber formation of NPC cells (6-10B) and also increases invasion and motility of 6-10B cells. DNP-mediated NPC metastasis also was confirmed in nude mice. Importantly, DNP induced the expression of phosphorylated ezrin (phos-ezrin) at threonine 567 (Thr-567) dose- and time-dependently but had no effect on the total ezrin expression at these concentrations. Furthermore, DNP-induced phos-ezrin expression was dependent on increased Rho kinase and protein kinase C (PKC) activity. DNP may activate Rho kinase through binding to its pleckstrin homology and may activate PKC through promoting its translocation to the plasma membrane in vivo. DNP-induced phos-ezrin was associated with induction of fiber growth in 6-10B cells. However, DNP could not induce motility and invasion of NPC cells containing ezrin mutated at Thr-567. Similarly, DNP could not induce motility and invasion of the cells containing siRNAs against Rho or PKC. These results indicate that DNP induces ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567, increases motility and invasion of cells, and promotes tumor metastasis. DNP may be involved in NPC metastasis through regulation of ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567.

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)3 is endemic in certain regions of the world, particularly in Southeast Asia with an incidence of 30–80 per 100,000 people per year in southern China (1). NPC has high invasive and metastatic features, and ∼90% of patients show cervical lymph node metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis (2). Therapeutic failures in advanced NPC have resulted from both high rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis. With recent advances in radiation oncology and chemotherapy, the patterns of failure have been predominantly due to distant metastasis (3–5).

Ezrin, a member of the ezrin/radixin/moesin family of cytoskeletal proteins, has been implicated in dynamic membrane-based processes such as the formation and stabilization of filopodia (6). Ezrin has also been shown to be involved in various cellular functions, including cell adhesion, migration, and organization of cell surface structure (7, 8). It may contribute to setting the scaffold between the actin cytoskeleton and a receptor for receptor retention (9). Ezrin mediates stress fiber formation (10), which is involved in cancer metastasis (11). High expression levels of ezrin are associated with tumor metastasis in lung cancer (12), prostate cancer (13), hepatocellular carcinoma (12), and NPC (14, 15). Additionally, further studies have revealed that ezrin is associated with early development of metastases (16, 17) and poor outcome in pediatric osteosarcoma patients (17). Furthermore, ezrin is significantly overexpressed in highly metastatic murine rhabdomyosarcoma and linked to metastatic behavior in different tumor types from diverse species (16). Overexpression of ezrin confers high metastatic capability to non-metastatic cells (16, 17). One important mechanism of regulating the function of ezrin is through phosphorylation at a conserved threonine residue (Thr-567) in its C terminus (18–21). Unphosphorylated ezrin exists in a folded conformation through intramolecular interactions, masking binding sites for other molecules. Phosphorylation on this conserved threonine residue causes conformational changes, unmasking binding sites (18, 21). Phosphorylation of ezrin at Thr-567 keeps it open and active and prolongs its lifetime (18). Phosphorylated ezrin (phos-ezrin) is involved in fiber formation, adhesion, and migration (15).

In studies on Chinese populations in high incidence regions, the relative risk of NPC associated with weekly salt-preserved fish consumption generally ranged from 1.4 to 3.2, whereas that for daily consumption ranged from 1.8 to 7.5 (24–29). The carcinogenic potential of salt-preserved fish is supported by experiments in rats, which develop malignant nasal carcinoma and NPC (30–32). The process of salt preservation is inefficient, allowing fish and other foods to become partially putrefied (33, 34). Consequently, these foods accumulate significant levels of nitrosamines, which are known carcinogens (33, 35–37). Consumption of salted fish is an important source of nitrosamines. N-Nitrosodimethylamine is a predominant volatile nitrosamine in salted fish. Some bacteria can also induce the conversion of nitrates into nitrites, forming important carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds (34). N,N′-Dinitrosopiperazine (DNP) is one predominant volatile nitrosamine in salted fish (28, 38, 39). Our previous work has shown that DNP can induce NPC without the complication of other cancers, demonstrates a constantly high rate of incidence, and displays organ specificity to nasopharyngeal epithelium (40). In the present study, we demonstrate a novel view of the mechanism of the metastatic features of NPC: DNP contributes to the metastasis of NPC through induction of phos-ezrin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

DNP was a kind gift from the Cancer Research Institute, Central South University (Hunan, China), and its chemical structure is shown at Fig. 1A. Chemical reagents, including Tris, HCl, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), Na2S2O3, K3Fe(CN)6, l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin, NH4HCO3, acrylamide, urea, thiourea, Nonidet P-40, Triton X-100, dl-dithiothreitol (DTT), phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), CHAPS, and Pharmalyte were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Lactate dehydrogenase assay reagents were purchased from Autec Diagnostica Co. (Botzing, Germany). Antibody against ezrin was purchased from Covance (Berkeley, CA). Antibodies against phos-ezrin Thr-567 or phos-ezrin Tyr-353 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Antibodies against phos-ezrin Tyr-146, Rho, PKC, G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2), myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase 2 (MRCK), lymphocyte-oriented kinase (LOK), PKCα, PKCβ1, PKCβ2, and PKCδ were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibody against β-actin and normal mouse IgG were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, NY). The secondary antibodies horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse immunoglobulin G and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Immunoblotting detection regents, glutathione-Sepharose 4B, BCA protein assay kit, and Coomassie Brilliant Blue G were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), FITC-phalloidin, DAPI, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTT), and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DNase I and RNase were purchased from Qiagen, Inc. (Valencia, CA) (15).

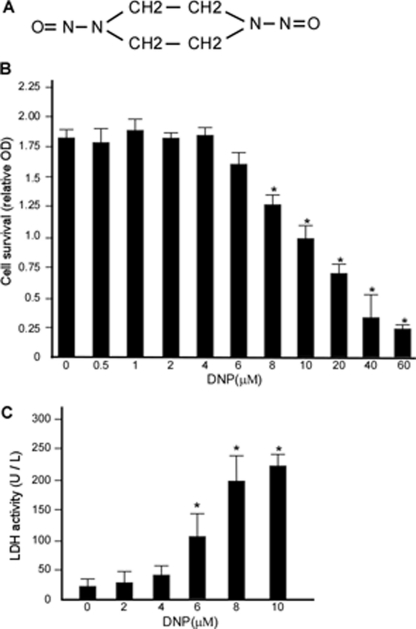

FIGURE 1.

Non-cytotoxic concentration of DNP in 6-10B cells. A, structure of DNP, an N-nitroso compound. B, 6-10B cells were treated with 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 20, 40, or 60 μm DNP for 48 h and then subjected to the MTT cell viability assay. C, 6-10B cells were treated with 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 μm DNP for 48 h, and cell media were subjected to the lactate dehydrogenase assay. OD indicates the relative optical density at 563 nm. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity is per 1 liter of media. Data are presented as means ± S.D. from three independent experiments statistically analyzed using the Student's t test (*, p < 0.05).

Cell Culture and DNP Treatment

The human NPC cell lines 5-8F and 6-10B, which are sublines derived from cell line SUNE-1, were purchased from the Cancer Research Institute of Sun Yatsen University (Guangzhou, China). The 5-8F cell line has a high metastatic ability, whereas the 6-10B cell line has a low metastatic ability (14). Cell lines were cultured as a monolayer in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml penicillin, and 100 IU/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) and were maintained in an incubator with a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For DNP treatment, DNP crystals were dissolved in DMSO, and appropriate amounts of the DNP stock solution were added to the culture cells to achieve the indicated concentrations. The cells were then incubated for the indicated times. To investigate the dose course of DNP treatment, cells were treated with 2 or 4 μm DNP for 24 h. For time course assays, cells were treated with 4 μm DNP for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h.

MTT Assay

To determine the non-cytotoxic concentration of DNP, the MTT assay was performed to determine the cell viability (15). Briefly, 6-10B cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3.5 × 103 cells/well and treated with 0 to ∼60 μm DNP for 24 h at 37 °C. After the exposure period, media were removed, and cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Thereafter, media were changed, and cells were incubated with 100 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml)/well for 4 h. The viable number of cells per dish was directly proportional to the production of formazan, which was solubilized in isopropanol and measured spectrophotometrically at 563 nm.

Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay

To further evaluate the non-cytotoxic concentration of DNP in NPC cells, lactate dehydrogenase activity in cell culture media was detected after DNP treatment. Briefly, 6-10B cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with 0–10 μm DNP for 24 h at 37 °C. After the exposure period, media were collected for lactate dehydrogenase activity measurement using the lactate dehydrogenase assay kit (Autec Diagnostica).

Immunofluorescence Analysis

6-10B cells treated with or without DNP were fixed with 2.0% formaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, washed three times with PBS, and then treated with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Cells were washed three times with PBS, stained with 5 μg/ml FITC-phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 40 min to detect microvilli, and then examined under a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) (15). Cells stained with DAPI served as a control, and cells with microvilli were counted.

Electron Microscopy

DNP-treated 6-10B cells were cultured on CELLocate coverslips (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). After incubation in a CO2 incubator for 30 min, cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. Cell samples were then processed conventionally and observed under a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Cells with stress fibers were counted (15).

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblotting assay was performed as described previously with some modifications (15). After DNP treatment, the cell samples were disrupted with 0.6 ml of lysis buffer (1× PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and freshly added 100 μg/ml PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mm sodium orthovanadate). The cell lysates were then subjected to a centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant protein concentration of each sample was determined using the BCA protein assay (Bio-Rad). 40 μg of protein of each sample was separated by a 10 or 12% polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The blot was subsequently incubated with 5% nonfat milk in PBS for 1 h to block nonspecific binding, incubated with specific antibody against ezrin (Covance) or phos-ezrin (Cell Signaling Technology) for 2 h, and then incubated with an appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. All incubations were carried out at 37 °C, and intensive PBS washing was performed after each incubation. After three PBS washes, the signal was developed by 4-chloro-1-napthol/3,3-o-diaminobenzidine, and relative photographic density was quantitated by a gel documentation and analysis system. β-Actin was used as an internal control to verify basal level expression and equal protein loading. The abundance ratio relative to β-actin was counted.

Radiobinding Assay of DNP to Rho Kinase

The affinity of DNP for the Rho kinase was determined by displacement of [3H]DNP from GST-Rho in vitro as described previously (41) with modifications in which an attempt was made to diminish the presence of a large excess of amine groups and protein during the approach to equilibrium. GST-Rho (30 μg) plus [3H]DNP and unlabeled DNP at various concentrations were incubated for 1 h at 30 °C. Samples were filtered over glass fiber GF/B filters using a Tomtec harvester and counted for radioactivity using a Wallac Betaplate counter as described previously (41). The apparent affinity of DNP and Rho kinase was determined (42).

Cell Motility and Invasion Assay

For the cell invasion assay, 6-10B cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of DNP for the indicated times. After DNP treatment, the cells were removed by trypsinization, and their invasiveness was tested by the Boyden chamber invasion assay in vitro (43). Matrigel (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) was diluted to 25 mg/50 ml with cold filtered distilled water and applied to 8-mm-pore size polycarbonate membrane filters. Treated cells were seeded into a Boyden chamber (Neuro Probe, Cabin John, MD) at the upper part at a density of 1.5 × 104 cells/well in 50 μl of serum-free-medium and then incubated for 12 h at 37 °C. The bottom chamber also contained standard medium with 20% FBS. The cells that invaded the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with methanol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A random field was counted for invaded cells under a light microscope.

To determine cell motility, cells were seed into a Boyden chamber on membrane filters that were not coated with Matrigel. Migration of cells was measured as described for the motility assay (43). For statistical analysis, a cell viability correction was applied to clarify the effect of DNP.

Animals

A total of 20 female nude BALB/c mice (∼5–6 weeks old) were purchased from the Animal Center of Central South University. They were maintained in the Laboratory for Experiments, Central South University under laminar airflow conditions. The studies were conducted according to the standards established by the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory by Animals of Central South University.

Evaluation of Effect of DNP on NPC Metastasis in Nude Mice

The metastatic effect of DNP on 6-10B cells was determined in vivo as described previously with some modifications (44). Briefly, 100-μl aliquots of 6-10B and 5-8F cell suspensions (1 × 104 cells) were mixed with Matrigel and then respectively injected into the tail veins of nude mice (10 mice/group). These mice were abdominally injected with DNP at a dosage of 40 mg/kg (body weight) twice a week for 60 days using a 1-ml sterile syringe (40). Metastasis was evaluated by measuring the weight of metastasized tumors at mediastinal lymph nodes on day 60. The present study protocols were approved by the ethics committee at Central South University.

In Vitro Kinase Activity Assay

The kinase activity assay was performed as described previously with some modifications (15). 6-10B cells (1.0 × 106) were cultured in 100-mm dishes for 12–24 h. After 70–80% confluence was reached and cells were starved for 24 h, the cells were treated with DNP for 24 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% FBS and then washed once with ice-cold PBS, disrupted in 250 μl of kinase lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mm β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm aprotinin, and 1 mm PMSF). The clarified supernatant fractions containing 500 μg of protein were subjected to immunoprecipitation using antibodies against Rho, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, or LOK, respectively. The precipitation-mediated ezrin phosphorylation was determined by the kinase assay protocol (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.). Briefly, 20 μg of immune complex was added to 2.5 μl of 10× kinase buffer (250 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mm β-glycerophosphate, 20 mm DTT, 1 mm Na3VO4, 100 mm MgCl2), 2.5 μl (2.5 μg) of a GST-ezrin fusion protein, 10 μl of diluted ATP mixture (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), 10 μCi of [32P]ATP, and H2O added to 25 μl. The reaction was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min and then subjected to separation by 12% SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie Blue and then dried. GST-phos-ezrin was analyzed by autoradiography to determine kinase activity.

Construction of Expression Vectors

pcDNA3.1 and pGEX-5x-1 vectors were purchased from Invitrogen. Ezrin DNA fragment was generated by PCR and cloned into the BamHI/XhoI site of the pcDNA3.1 vector (Amersham Biosciences) to generate pcDNA3.1-Ezrin plasmids. Ezrin fragment was cloned into the BamHI/XhoI site of pGEX-5x-1 to generate pGEX-5x-1-Ezrin. The mutant pcDNA3.1-Ezrin plasmid was generated by the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit and ezrin mutant primers: Primer 1 (sense), 5′-cagggcaacgccaagcagcgcat-3′; Primer 2 (antisense), 5′-atgcgctgcttggcgttgccctg-3′. Primer 1 was combined with Primer 2 for mutating Thr-567 into Ala-567 to generate pcDNA3.1-Ezrin Ala-567 (pcDNA3.1-Ezrin M). The pU6pro vector was used to construct pU6pro-si-mock (si-mock) and pU6prosi-Rho (si-Rho) following the recommended protocol. Primers were synthesized for the si-mock (general scramble: sense, 5′-TTTGACTACCGTTGTTATAGGTGTTCAAGAGACACCTATAACAACGGTAGTTTTTT-3′; antisense, 5′-CTAGAAAAAACTACCGTTGTTATAGGTGTCTCTTGAACACCTATAACAACGGTAGT-3′) and for si-Rho (general scramble: sense, 5′-CCAAAUACCUCCUCAGUAATT-3′; antisense, 5′-GAAGAUAAAUCGUGCACUATT-3′) (45). si-PKC was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. All constructs were confirmed by restriction enzyme mapping and DNA sequencing

Immunoblotting Analysis of PKC Translocation

The preparation of membrane and cytosol was performed at 4 °C. The cells were homogenized in lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris. The upper fractions were centrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting pellet was suspended in lysis buffer, the supernatant was concentrated using centrifugal filtration (Ultrafree MC, Millipore, Bedford, MA), and these two components were then saved as membrane and cytosol fractions, respectively. PKC in membrane and cytosol fractions was detected using immunoblotting.

In Vitro Binding Assay of DNP with Rho Kinase

pGEX-5x-1-Rho, pGEX-5x-1-Rho-delRBD, pGEX-5x-1-Rho-delPH, pGEX-5x-1-Rho-delCRD, and pGEX-5x-1 were transformed into BL21 Escherichia coli. The expressions of GST-Rho, Rho-delRBD, Rho-delPH, and Rho-delCRD were induced by isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside, and recombinant Rho proteins were purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences). 2 μg of GST-Rho, Rho-delRBD, Rho-delPH, and Rho-delCRD was incubated with 1 μCi of [3H]DNP at 4 °C for 2 h. These reactive products were separated by SDS-PAGE for autoradiography and Coomassie Blue staining.

Gene Transfection and Stable Transfection of Cells

6-10B cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 (mock), pcDNA3.1-Ezrin, or pcDNA3.1-Ezrin M, respectively, using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's suggested protocol. For establishing 6-10B-si-Rho or 6-10B-si-PKC cells, 6-10B cells were transfected with pU6pro-si-Rho or pU6pro-si-PKC, respectively. The stably transfected cell lines were obtained by selection for G418 resistance and further confirmed by assessing Rho or PKC expression.

RESULTS

Non-cytotoxic Concentration of DNP in 6-10B Cells

DNP is an important carcinogenic N-nitroso compound, and its chemical structure is shown in Fig. 1A. In the present study, we determined the non-cytotoxic concentration of DNP by treating 6-10B cells. Compared with the control (0.01% DMSO), cell viability was not significantly altered at 0.5–4 μm DNP (Fig. 1B; *, p < 0.05). To further confirm that 0.5–4 μm DNP was non-cytotoxic, lactate dehydrogenase activity in the cell culture media was detected after DNP treatment. The data revealed that lactate dehydrogenase activity was not significantly altered between 0.5 and 4 μm (Fig. 1C; *, p < 0.05). Thus, this non-cytotoxic concentration range was used in all subsequent experiments.

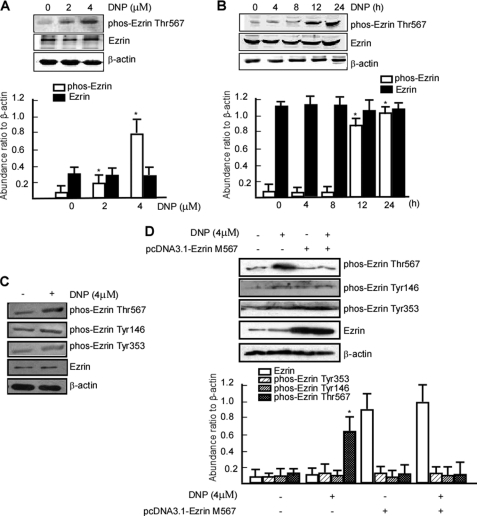

DNP Induces Expression of Phos-ezrin at Thr-567

The 6-10B NPC cell line with low ezrin expression was used to investigate whether DNP could induce ezrin expression (15). To confirm whether DNP can induce phos-ezrin Thr-567 expression, 6-10B cells were treated with 2–4 μm DNP for dose course assays or with 4 μm DNP for 4–24 h for time course assays, and then ezrin and phos-ezrin expression was detected using immunoblotting. DNP induced phos-ezrin Thr-567 expression in a dose- (Fig. 2A) and time-dependent (Fig. 2B) manner but did not induce total ezrin expression (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition to phosphorylation site Thr-567, ezrin can be phosphorylated at Tyr-146 and Tyr-353. To probe whether DNP triggers ezrin phosphorylation at other sites, phosphorylation of ezrin at Tyr-146 and Tyr-353 was determined. Ezrin phosphorylation was not detected at Tyr-146 (Fig. 2C, right versus left lane in second panel) or at Tyr-353 (Fig. 2C, right versus left lane in third panel) in DNP-treated 6-10B cells. To further confirm that DNP induces ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567, ezrin Thr-567 was mutated to Ala-567, and the ezrin mutant was transfected into 6-10B cells. DNP did not induce phosphorylation of the ezrin mutant (Fig. 2D) and also did not induce ezrin phosphorylation at Tyr-146 or Tyr-353. Thus, DNP induces ezrin phosphorylation only at Thr-567.

FIGURE 2.

Effects of DNP on ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567. 6-10B cells were treated with 2 or 4 μm DNP for 24 h (A) and with 4 μm DNP for 4, 8, 12 or 24 h (B), and ezrin and phos-ezrin expression was assayed by immunoblotting. Cells treated with 0.01% DMSO in PBS (the solvent solution of DNP) served as a control. After treatment with DNP, ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567, Tyr-146, or Tyr-353 was detected (C). To further confirm DNP-induced ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567, 6-10B cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Ezrin M (A) followed by treatment with DNP. Ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567, Tyr-146, or Tyr-353 was detected (D).

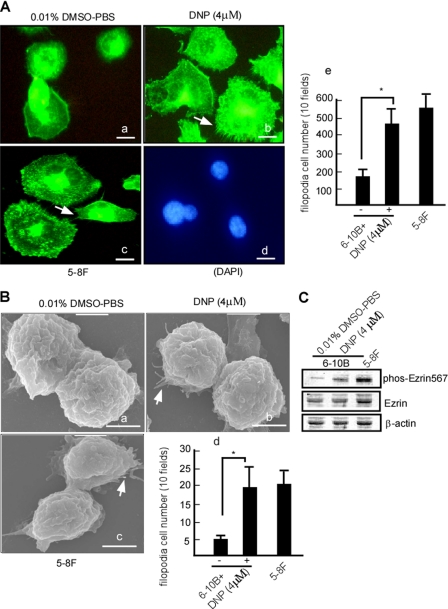

DNP Induces Fiber Growth of 6-10B Cells

Ezrin is closely associated with filopodia and fiber growth, and phosphorylation of ezrin causes elongation of filopodia and fibers (6, 46). We next determined whether DNP-induced phos-ezrin is involved in filopodia and fiber formation. Growth of microvilli was observed in DNP-treated 6-10B cells using immunofluorescence. Compared with the control (Fig. 3A, panel a and panel e, lane 1), formation of microvilli of 6-10B cells was increased by 68.7 ± 15.6% after DNP treatment (Fig. 3A, panel b and panel e, lane 2 versus lane 1; *, p < 0.05). To further confirm this finding, cell fibers were observed by scanning electron microscopy, which showed that the fiber growth of 6-10B cells increased 69.7 ± 2.8% upon DNP treatment (Fig. 3B, panel b and panel d, lane 2 versus lane 1; *, p < 0.05). Ezrin and phos-ezrin expression levels in these samples were also detected by immunoblotting. Phos-ezrin at Thr-567 increased 3.8-fold after DNP treatment (Fig. 3C, upper panel, right versus left lane), but total ezrin expression was not altered (Fig. 3C, middle panel, right versus left lane), suggesting that DNP can trigger phos-ezrin expression, inducing fiber growth.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of DNP on fiber and microvillus formation in 6-10B cells. 6-10B cells were treated with 4 μm DNP for 48 h. A, 6-10B cells were stained with FITC-phalloidin: panel a, 6-10B cells treated with 0.01% DMSO; panel b, 6-10B cells treated with 4 μm DNP; panel c, 5-8F cells served as a control; panel d, 5-8F cells stained with DAPI; panel e, cells with microvilli were counted. Scale bar, 20 μm. Arrows, microvilli. B, cells were observed under scanning electron microscopy: panel a, 6-10B cells treated with 0.01% DMSO; panel b, 6-10B cells treated with 4 μm DNP; panel c, 5-8F cells served as a control; panel d, cells with fibers were counted. Scale bar, 5 μm. Arrows, fibers. C, cells after treatment with DNP. Ezrin and phos-ezrin expression was determined using immunoblotting. β-Actin served as the loading control.

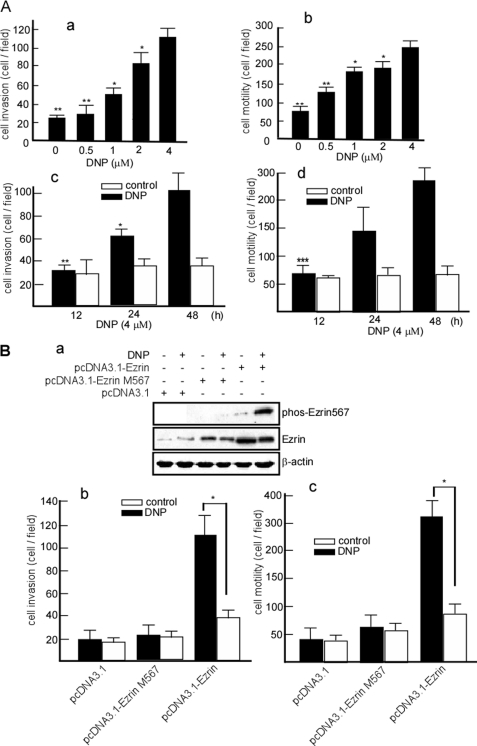

DNP Induces Invasion and Motility of 6-10B Cells

Fibers are associated with cell motility and invasion (47). To determine whether DNP can induce invasion and motility of cells, Matrigel-coated Boyden chambers were used to measure cell motility and invasion. For dose course experiments, 6-10B cells were treated with 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 μm DNP for 24 h and then seeded into Boyden chambers. The cells that invaded the lower chamber were counted. The cells that invaded the lower chamber increased after DNP treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A, panel a, lanes 2-5 versus lane 1; *, p < 0.05). The increase was 63.8% with 4 μm DNP (Fig. 4A, panel a, lane 5). A similar effect was observed for the motility of DNP-treated cells (Fig. 4A, panel b, lanes 2-5 versus lane 1; *, p < 0.05). Cell motility increased by 68% after treatment with 4 μm DNP (Fig. 4A, panel b, lane 5). To effectively observe the time course of these effects, cells were treated with 4 μm DNP for 12, 24, and 48 h. We found that DNP increased invasion (Fig. 4A, panel c, lane 3 versus lane 4 and lane 5 versus lane 6; *, p < 0.05) and motility (Fig. 4A, panel d, lane 3 versus lane 4 and lane 5 versus lane 6; *, p < 0.05) in a time-dependent manner with the effects prolonged to 48 h. These results indicate that DNP can induce NPC cell motility and invasion. To confirm whether DNP-induced motility and invasion is through phos-ezrin Thr-567, pcDNA3.1, pcDNA3.1-Ezrin M, and pcDNA3.1-Ezrin, respectively, were transfected into 6-10B-siRNA ezrin cells, and then the invasion and motility of the transfectants were detected. After DNP treatment, the invasion (Fig. 4B, panel b, lane 5 versus lane 6; *, p < 0.05) and motility (Fig. 4B, panel c, lane 5 versus lane 6; *, p < 0.05) of cells dramatically increased in the transfectant with pcDNA3.1-Ezrin but did not increase in the transfection with pcDNA3.1 (Fig. 4B, panel b, lane 1 and panel c, lane 1) or pcDNA3.1-Ezrin M (Fig. 4B, panel b, lane 3 and panel c, lane 3). This indicates that DNP induces NPC cell motility and invasion through phos-ezrin Thr-567.

FIGURE 4.

DNP-mediated 6-10B cell invasion and motility in vitro. A, concentration and time course effects of DNP on motility and invasion of 6-10B cells. In concentration course assays, 6-10B cells were treated with 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 μm DNP for 24 h. In time course assays, cells were treated with 4 μm DNP for 12, 24, or 48 h. Treated cells were subjected to analyses for motility and invasion as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Panel a, invasion of 6-10B cells at various concentrations; panel b, motility of 6-10B cells at various concentrations; panel c, invasion of 6-10B cells at various time points; panel d, motility of 6-10B cells at various time points. B, pcDNA3.1-Ezrin and pcDNA3.1-Ezrin M were transfected into 6-10B-siRNA ezrin cells, and then ezrin and phos-ezrin were detected in the transfectants (panel a), and the invasion (panel b) and motility (panel c) of the transfectants were detected. Results were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

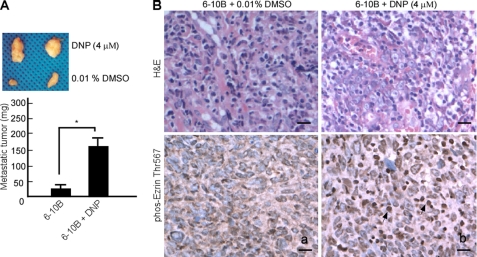

The metastasis-inducing effects of DNP were confirmed in vivo when 6-10B cells were injected into the tail veins of BALB/c mice. Metastasis of 6-10B cells to the mediastinal lymph nodes significantly increased after DNP treatment (Fig. 5A, lane 2 versus lane 1; *, p < 0.05). To determine whether these effects are associated with ezrin phosphorylation, phos-ezrin was detected in metastatic tumors by immunohistochemistry. Phos-ezrin levels were higher in metastatic tumors from DNP-treated mice (Fig. 5B, panel b) than in those from untreated control mice (Fig. 5B, panel a).

FIGURE 5.

DNP-mediated 6-10B cell metastasis in vivo. A, 20 nude mice were injected with 6-10B cells in Matrigel through the tail vein (1 × 104 cells/mouse) and then randomly divided into two groups with 10 mice per group. One group was abdominally injected with DNP at a dosage of 40 mg/kg (body weight) twice a week for 60 days using 1-ml sterile syringe. The other group was injected with saline. After 60 days, metastatic tumors from the mediastinal lymph nodes were weighed. Scale bar, 0.5 cm (*, p < 0.05). B, ezrin and phos-ezrin were detected in the metastatic tumor samples using immunochemistry. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin as well as with antibodies against phos-ezrin Thr-567. Panel a, untreated 6-10B cells as control; panel b, DNP-treated 6-10B cells. Arrows, positive cells. Original magnification, ×400. Scale bar, 5 μm.

DNP Activates Rho Kinase via Binding to Rho PH and PKC via Promoting PKC Membrane Translocation

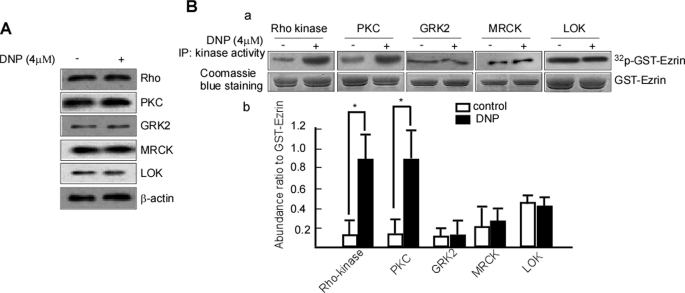

Ezrin is known to be phosphorylated by several protein kinases, including Rho kinase, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK (18, 48–51). To identify the upstream kinases of DNP-induced ezrin phosphorylation, we determined whether DNP could increase the expression or activities of Rho kinase, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK. 6-10B cells were treated with 4 μm DNP, and the protein expression of Rho, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK was detected by immunoblotting. Protein expression of Rho, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK was not altered (Fig. 6A). Additionally, Rho, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK were immunoprecipitated from the treated cultures, and an in vitro kinase assay was used to detect their respective activities. Rho kinase activity (Fig. 6B, panel a, upper panel, lane 2 versus lane 1 and panel b, lane 2 versus lane 1; *, p < 0.05) and PKC activity (Fig. 6B, panel a, upper panel, lane 4 versus lane 3 and panel b, lane 3 versus lane 4; *, p < 0.05) dramatically increased with DNP treatment, whereas the activities of GRK2, MRCK, and LOK remained unchanged (Fig. 6B, panel a, upper panel, lane 6 versus lane 5, lane 8 versus lane 7, and lane 10 versus lane 9 and panel b, lane 6 versus lane 5, lane 8 versus lane 7, and lane 10 versus lane 9). These data suggest that DNP only increases Rho kinase and PKC activities.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of DNP on Rho kinase and PKC activity. A, expressions of Rho, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK were determined in the cells with or without DNP treatment by immunoblotting. B, the activities of PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK were detected. Briefly, GST-ezrin phosphorylation mediated by Rho kinase, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, or LOK was assayed using an in vitro kinase assay (panel a, b). Coomassie Blue staining served as the loading control. IP, immunoprecipitation.

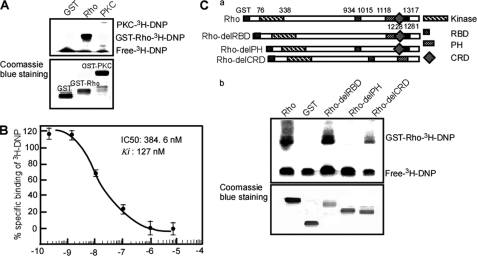

To clarify the mechanism of DNP activating of Rho kinase and PKC, the first step was to observe the interaction of DNP with Rho kinase and PKC, respectively. The data showed that DNP bound to Rho kinase (Fig. 7A, upper panel, lane 2) but not PKC (Fig. 7A, upper panel, lane 3). To further investigate the binding of DNP and Rho, a competition binding assay was used to test the interaction of DNP with Rho. The results showed that the IC50 of DNP binding to Rho was 384.6 nm, and Ki was 127 nm. This implies that DNP covalently binds to Rho (Fig. 7B). The Rho kinase sequence comprises a kinase domain followed by a coiled coil region containing the Rho-binding domain (RBD) and PH domain with a cysteine-rich domain. The RBD and PH domains regulate Rho kinase activity, and binding to these domains is able to efficiently increase Rho kinase activity (52). To further determine the binding domain of Rho kinase with DNP, we constructed the vectors containing the full length and three deletion mutants of Rho kinase (Fig. 7C, panel a) to identify the binding domain of DNP. Results indicated that if the C-terminal amino acids 1118–1228 (PH domain) were deleted DNP did not bind to Rho kinase, whereas full-length Rho kinase could interact with DNP (Fig. 7C, panel b), suggesting that DNP binds the PH domain of Rho kinase. DNP may activate Rho kinase through binding to the PH domain.

FIGURE 7.

Binding of DNP with Rho kinase and PKC. A, binding assay of DNP with Rho kinase or PKC. GST, GST-Rho, GST-PKC proteins were incubated with [3H]DNP, and then reactive mixtures were separated by SDS-PAGE for autoradiography. B, affinity of DNP for Rho kinase. This affinity was determined by displacement of [3H]DNP from GST-Rho. The IC50 of DNP interaction with Rho was 384.6 nm, and Ki was 127 nm. C, domain of Rho interaction with DNP. Various domains (panel a), Rho-delRBD, Rho-delPH, Rho-delCRD, and GST, respectively, were incubated with [3H]DNP, and reactive complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE for autoradiography (panel b).

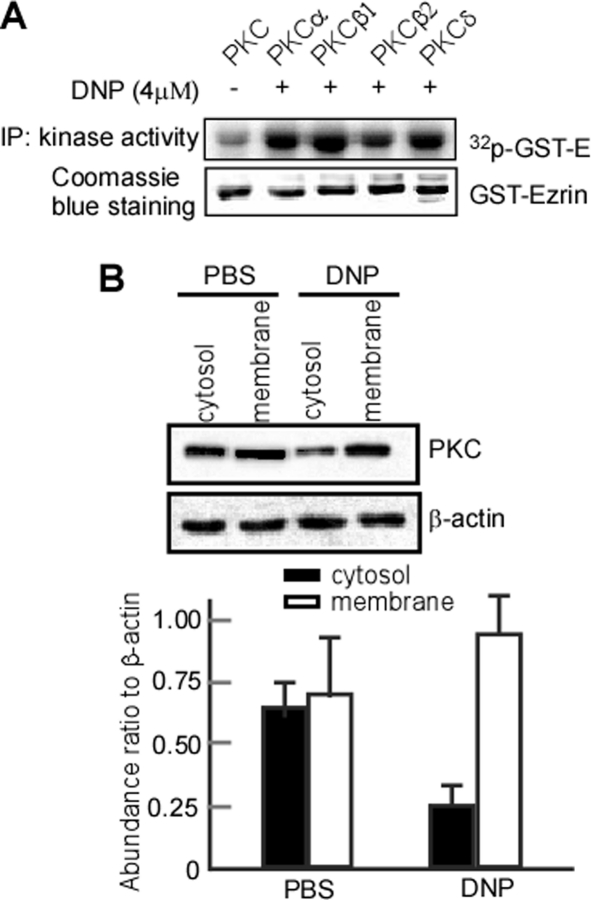

In the above experiment, we found that DNP activates PKC. To further identify which PKC subunit is involved in this process, PKCα, PKCβ1, PKCβ2, and PKCδ were immunoprecipitated, and their respective ezrin phosphorylation was detected. The results showed that all PKCα, PKCβ1, PKCβ2, and PKCδ activities were increased after DNP treatment (Fig. 8A, upper panel, lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5). Additionally, PKC translocation to the plasma membrane has generally been considered the hallmark of activation (53). To explore the possibility that DNP activates PKC through promotion of PKC translocation, we performed immunoblotting analyses to test PKC in the cytosol and membrane. Exposure of 6-10B cells to DNP increased membrane PKC (Fig. 8B, upper panel, lane 4) compared with the control (Fig. 8B, upper panel, lane 2). These findings suggest that DNP activates PKC through promoting its translocation to the membrane.

FIGURE 8.

Activity assay of PKC subunits and PKC nuclear translocation in 6-10B cells with DNP treatment. A, PKC subunit activities were assayed in vitro. After 6-10B cells were treated with DNP, PKC, PKCα, PKCβ1, PKCβ2, and PKCδ were immunoprecipitated. Ezrin phosphorylation mediated by these immunoprecipitations was detected. Phosphorylated GST-Ezrin was analyzed by autoradiography, and then kinase activity was determined. B, PKC expression in the membrane and cytosol. After treatment with DNP, the cells were homogenized in lysis buffer. The membrane and cytosol fractions were separated using centrifugal filtration as described. PKC in membrane and cytosol fractions was detected using immunoblotting. IP, immunoprecipitation.

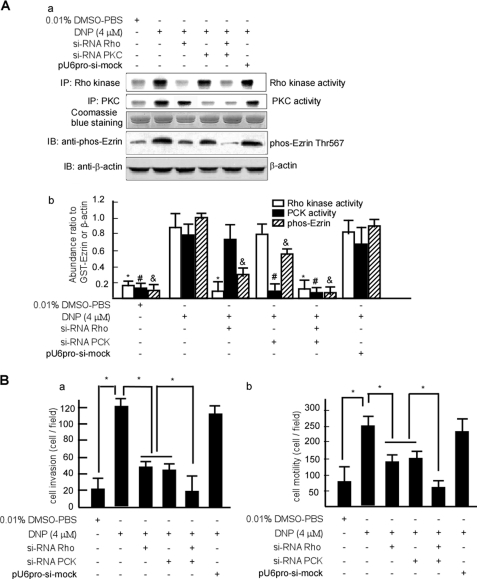

DNP Promotes Metastasis through Ezrin Phosphorylation at Thr-567 by Rho Kinase and PKC

To confirm whether DNP mediates phos-ezrin through Rho kinase or PKC, 6-10B cells were transfected with pU6pro-si-Rho or pU6pro-si-PKC to block Rho or PKC, respectively. The stably transfected cell lines 6-10B-si-Rho and 6-10B-si-PKC were obtained by selection for G418 resistance and further confirmed by assessing Rho or PKC activity. The kinase activities of Rho and PKC were silenced in 6-10B-si-Rho (Fig. 9A, panel a, upper panel, lane 3 and panel b, lane 7; *, p < 0.05) and 6-10B-si-PKC cells, respectively (Fig. 9A, panel a, second panel, lane 4 and panel b, lane 11; #, p < 0.05). To achieve silencing of both Rho and PKC, 6-10B-si-Rho cells were transiently transfected with pU6pro-si-PKC (Fig. 9A, panel a, upper panel, lane 5 and second panel, lane 5 and panel b, lanes 13 and 14; * and #, p < 0.05). Phos-ezrin at Thr-567 was detected in these stable transfected cells after DNP treatment. DNP did not induce phos-ezrin expression when Rho and PKC were blocked (Fig. 9A, panel a, fourth panel, lanes 3, 4, and 5 and panel b, lanes 13, 14, and 15; &, p < 0.05).

FIGURE 9.

DNP-mediated motility and invasion through Rho kinase and PKC. A, 6-10B cells were transfected with pU6pro-si-Rho, pU6pro-si-PKC, or pU6pro-si-mock, and then stable cell lines 6-10B-si-Rho, 6-10B-si-PKC, and 6-10B-si-mock were obtained by selection for G418 resistance. Rho kinase and PKC activities as well as phos-ezrin expression were detected in these cells with or without DNP treatment. Coomassie Blue staining is shown as a loading control. The abundance ratios relative to β-actin or GST-ezrin were calculated, and data are expressed as means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, #, and &, p < 0.05. IP, immunoprecipitation. B, the motility (panel a) and invasion (panel b) of 6-10B-si-Rho, 6-10B-si-PKC, and 6-10B-si-mock cells. Data are presented as means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. Results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's test (*, p < 0.05). IB, immunoblotting.

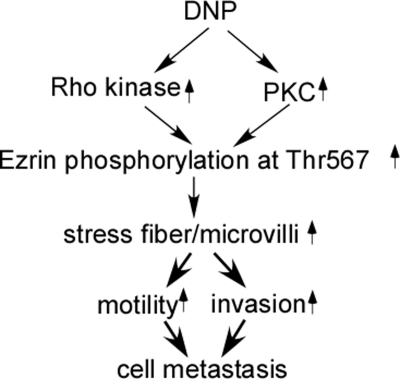

To further confirm whether DNP induces cell motility and invasion through Rho kinase or PKC, cell motility and invasion were detected in these cell lines with Rho kinase or PKC blocked. DNP-induced motility and invasion were dramatically decreased when Rho kinase and PKC were blocked (Fig. 9B, panel a, lanes 3 and 4 and panel b, lanes 3 and 4; *, p < 0.05). When both Rho kinase and PKC were blocked, cell motility and invasion were lower than when Rho kinase or PKC were blocked individually (Fig. 9B, panel a, lane 5 and panel b, lane 5; *, p < 0.05). Taken together, our data indicate that DNP induces ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567 via induction of Rho kinase and PKC activities, resulting in enhanced growth of microvilli and fibers, Rho kinase regulating fiber while not Cdc42 (supplemental Data 3), increased motility and invasion of cells, and finally NPC cell metastasis (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

Schematic illustration of DNP-induced metastasis. DNP-mediated ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567 through Rho kinase activity increases stress fibers and microvilli and promotes motility and invasion, leading to metastasis of NPC cells.

DISCUSSION

Well established carcinogenic factors for NPC include EBV infection, consumption of salt-preserved fish, and a family history of NPC (54, 55). Consumption of salted fish in which the predominant volatile nitrosamine N-nitrosodimethylamine can form has been suspected to be a risk factor for NPC (33, 35, 37). DNP, a volatile nitrosamine, induces NPC with metastasis in rats (38). Clinically, NPC has a high metastatic potential (2) and NPC patients have high concentration DNP (supplemental Data 1), but the molecular mechanism of NPC with high metastasis is unclear. We present two lines of evidence demonstrating that the carcinogen DNP is involved in NPC metastasis. First, DNP can induce 6-10B cell motility and invasion in vitro. Second, DNP can increase cell metastasis of mediastinal lymph nodes in vivo.

Stress fibers are involved in cell motility (22). The present study demonstrates that DNP induces fiber formation in 6-10B cells. Phos-ezrin regulates stress fiber information (10). DNP may mediate cell motility and invasion through regulation of stress fibers. Additionally, ezrin is an important component of microvilli of epithelial cells and serves as a major cytoplasmic substrate for certain protein-tyrosine kinases. It has been implicated in dynamic membrane-based processes such as the formation and stabilization of microvilli (6). High expression of ezrin is associated with tumor metastasis (12–14, 23), including that of NPC (14). Ezrin may also control multiple pathways and promote tumor metastasis (17). 6-10B cells with low metastatic ability and ezrin expression were used to investigate the effect of DNP on the motility and invasion of NPC cells. However, we did not find that DNP induced ezrin expression even though DNP increased 6-10B cell metastasis.

Because ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567 is one important way to regulate the function of ezrin (18–21), we investigated the effect of DNP on ezrin phosphorylation. Intriguingly, DNP effectively induced ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567 at the C terminus. Ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567 keeps the protein open and active and prolongs its lifetime (18). Additionally, phos-ezrin with an open conformation may function as an actin filament/plasma membrane cross-linker (18–20). We speculated that DNP may induce NPC metastasis through regulation of ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567. To further confirm this hypothesis, we established stably transfected cell lines containing ezrin or mutated ezrin (Thr-567 mutated to Ala-567) and observed the effects of DNP on cell motility and invasion. Interestingly, DNP induced cell motility and invasion in cells transfected with ezrin but did not induce these effects in cells transfected with the ezrin mutant. As a cytoskeleton organizer, ezrin is involved in various cellular functions such as cell adhesion, migration, and organization of cell surface structure (7, 8). Phosphorylation at a conserved threonine residue in the C terminus (Thr-567) is an important mechanism for regulating the function of ezrin (21), including its important role in cell metastasis. The induction of ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567 by DNP may be involved in the metastasis of NPC cells.

Rho kinase, PKC, GRK2, MRCK, and LOK can phosphorylate ezrin (18, 48, 50, 51). But, our data show that DNP could only increase Rho kinase and PKC activity, and DNP-mediated ezrin phosphorylation was only dependent on Rho kinase and PKC. DNP covalently bound to the PH domain of Rho kinase and promoted PKC translocation to the membrane. These results suggest that DNP activates Rho kinase via binding its PH domain and activated PKC (including PKCα, PKCβ1, PKCβ2, and PKCδ subunits) through promoting its translocation. However, DNP could not directly activate Rho kinase and PKC in vitro (supplemental Data 2), and DNP mediated ezrin phosphorylation after treatment for 12 h (Fig. 2B). Based on these results, we speculated that DNP may activate Rho kinase through mediating other molecules and together binding to the PH domain or through another mechanism. We believe that Rho kinase and PKC may be upstream components in DNP-mediated ezrin phosphorylation. Herein, we have provided three lines of evidence that support DNP involvement in the metastasis of NPC cells through induction of ezrin phosphorylation. The first is that DNP induces motility and invasion of 6-10B cells following ezrin phosphorylation at Thr-567. The second is that DNP enhances lymph node metastasis of NPC cells in nude mice, and phos-ezrin is highly expressed in lymph metastatic samples. Finally, DNP-mediated ezrin phosphorylation is dependent on Rho kinase or PKC activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Director Tieyong Li at the Cancer Research Institute of Central South University for providing DNP and Prof. Haiying Jian and Deyun Feng at the Department of Pathology of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University and Youping Sun of BEST Inc. for support.

This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81071718, 81000881, 30973400, and 30572455; Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University Grant NCET-06-0685; Technology Foundation of Hunan Grant 08FJ3176; and Science Foundation of Central South University Grant 08SDF07.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Data 1, 2, and 3, which include supplemental Figs. S1 and S2 and a table.

- NPC

- nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- DNP

- N,N′-dinitrosopiperazine

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- RBD

- Rho-binding domain

- GRK2

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2

- phos-ezrin

- phosphorylated ezrin

- MRCK

- myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase 2

- LOK

- lymphocyte-oriented kinase

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium

- CRD

- cysteine-rich domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. (1987) IARC Sci. Publ. 88, 1–970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leung T. W., Tung S. Y., Sze W. K., Wong F. C., Yuen K. K., Lui C. M., Lo S. H., Ng T. Y., O S. K. (2005) Head Neck 27, 555–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang S. C., Lui L. T., Lynn T. C. (1985) Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 11, 1789–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chua D. T., Sham J. S., Kwong D. L., Wei W. I., Au G. K., Choy D. (1998) Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 41, 379–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al-Sarraf M., LeBlanc M., Giri P. G., Fu K. K., Cooper J., Vuong T., Forastiere A. A., Adams G., Sakr W. A., Schuller D. E., Ensley J. F. (1998) J. Clin. Oncol. 16, 1310–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Furutani Y., Matsuno H., Kawasaki M., Sasaki T., Mori K., Yoshihara Y. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 8866–8876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saotome I., Curto M., McClatchey A. I. (2004) Dev. Cell 6, 855–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faure S., Salazar-Fontana L. I., Semichon M., Tybulewicz V. L., Bismuth G., Trautmann A., Germain R. N., Delon J. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 272–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roumier A., Olivo-Marin J. C., Arpin M., Michel F., Martin M., Mangeat P., Acuto O., Dautry-Varsat A., Alcover A. (2001) Immunity 15, 715–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yasui Y., Amano M., Nagata K., Inagaki N., Nakamura H., Saya H., Kaibuchi K., Inagaki M. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 143, 1249–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Merajver S. D., Usmani S. Z. (2005) J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 10, 291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Y., Hu M. Y., Wu W. Z., Wang Z. J., Zhou K., Zha X. L., Liu K. D. (2006) J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 132, 685–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chuan Y. C., Pang S. T., Cedazo-Minguez A., Norstedt G., Pousette A., Flores-Morales A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29938–29948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang X. Y., Ren C. P., Wang L., Li H., Jiang C. J., Zhang H. B., Zhao M., Yao K. T. (2005) Cell. Oncol. 27, 215–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang F., Wang D., Duan C., Huang D., Wu Y., Chen Y., Wang W., Xie C., Meng J., Wang L., Wu B., Liu S., Tian D., Zhu F., He Z., Deng F., Cao Y. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27456–27466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu Y., Khan J., Khanna C., Helman L., Meltzer P. S., Merlino G. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khanna C., Wan X., Bose S., Cassaday R., Olomu O., Mendoza A., Yeung C., Gorlick R., Hewitt S. M., Helman L. J. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 182–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matsui T., Maeda M., Doi Y., Yonemura S., Amano M., Kaibuchi K., Tsukita S., Tsukita S. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 140, 647–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen J., Cohn J. A., Mandel L. J. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7495–7499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yonemura S., Matsui T., Tsukita S., Tsukita S. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 2569–2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu L., Zhou R., Mettler S., Wu T., Abbas A., Delaney J., Forte J. G. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C874–C884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Naumanen P., Lappalainen P., Hotulainen P. (2008) J. Microsc. 231, 446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deng X., Tannehill-Gregg S. H., Nadella M. V., He G., Levine A., Cao Y., Rosol T. J. (2007) Clin. Exp. Metastasis 24, 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Henderson B. E., Louie E. (1978) IARC Sci. Publ. 251–260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu M. C., Ho J. H., Lai S. H., Henderson B. E. (1986) Cancer Res. 46, 956–961 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu M. C., Huang T. B., Henderson B. E. (1989) Int. J. Cancer 43, 1077–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong R. W., Imrey P. B., Lye M. S., Armstrong M. J., Yu M. C., Sani S. (1998) Int. J. Cancer 77, 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuan J. M., Wang X. L., Xiang Y. B., Gao Y. T., Ross R. K., Yu M. C. (2000) Int. J. Cancer 85, 358–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zou J., Sun Q., Akiba S., Yuan Y., Zha Y., Tao Z., Wei L., Sugahara T. (2000) J. Radiat. Res. 41, (suppl.) 53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zheng X., Luo Y., Christensson B., Drettner B. (1994) Acta Otolaryngol. 114, 98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu M. C., Nichols P. W., Zou X. N., Estes J., Henderson B. E. (1989) Br. J. Cancer 60, 198–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang D. P., Ho J. H., Saw D., Teoh T. B. (1978) IARC Sci. Publ. 315–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zou X. N., Lu S. H., Liu B. (1994) Int. J. Cancer 59, 155–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bartsch H., Ohshima H., Pignatelli B., Calmels S. (1992) Pharmacogenetics 2, 272–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Preston-Martin S., Correa P. (1989) Cancer Surv. 8, 459–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jakszyn P., Gonzalez C. A. (2006) World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 4296–4303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Poirier S., Hubert A., de-Thé G., Ohshima H., Bourgade M. C., Bartsch H. (1987) IARC Sci. Publ. 415–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen Z. C., Pan S. C., Yao K. T. (1991) IARC Sci. Publ. 434–438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gallicchio L., Matanoski G., Tao X. G., Chen L., Lam T. K., Boyd K., Robinson K. A., Balick L., Mickelson S., Caulfield L. E., Herman J. G., Guallar E., Alberg A. J. (2006) Int. J. Cancer 119, 1125–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tang F. Q., Duan C. J., Huang D. M., Wang W. W., Xie C. L., Meng J. J., Wang L., Jiang H. Y., Feng D. Y., Wu S. H., Gu H. H., Li M. Y., Deng F. L., Gong Z. J., Zhou H., Xu Y. H., Tan C., Zhang X., Cao Y. (2009) Cancer Sci. 100, 216–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Meschler J. P., Howlett A. C. (1999) Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 62, 473–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Howlett A. C., Wilken G. H., Pigg J. J., Houston D. B., Lan R., Liu Q., Makriyannis A. (2000) J. Neurochem. 74, 2174–2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Attiga F. A., Fernandez P. M., Weeraratna A. T., Manyak M. J., Patierno S. R. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 4629–4637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mitani N., Murakami K., Yamaura T., Ikeda T., Saiki I. (2001) Cancer Lett. 165, 35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chang T. C., Chen Y. C., Yang M. H., Chen C. H., Hsing E. W., Ko B. S., Liou J. Y., Wu K. K. (2010) PLoS One 5, e9187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gallo G. (2008) Dev. Neurobiol. 68, 926–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schäfer C., Borm B., Born S., Möhl C., Eibl E. M., Hoffmann B. (2009) Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1212–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Belkina N. V., Liu Y., Hao J. J., Karasuyama H., Shaw S. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4707–4712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jiménez-Sainz M. C., Murga C., Kavelaars A., Jurado-Pueyo M., Krakstad B. F., Heijnen C. J., Mayor F., Jr., Aragay A. M. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 25–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cant S. H., Pitcher J. A. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3088–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ng T., Parsons M., Hughes W. E., Monypenny J., Zicha D., Gautreau A., Arpin M., Gschmeissner S., Verveer P. J., Bastiaens P. I., Parker P. J. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2723–2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Amano M., Fukata Y., Kaibuchi K. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 261, 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Steinberg S. F. (2004) Biochem. J. 384, 449–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chang E. T., Adami H. O. (2006) Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1765–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu M. C., Yuan J. M. (2002) Semin. Cancer Biol. 12, 421–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.