Abstract

This paper extends the Tiger, Hanley, and Bruzek (2008) review of functional communication training (FCT) by reviewing the published literature on reinforcement schedule thinning following FCT. As noted by Tiger et al. and others, schedule thinning may be necessary when the newly acquired communication response occurs excessively, to the extent that reinforcing it consistently is not practical in the natural environment. We provide a review of this literature including a discussion of each of the more commonly used schedule arrangements used for this purpose, outcomes obtained, a description of methods for progressing toward the terminal schedule, and a description of supplemental treatment components aimed at maintaining low levels of problem behavior during schedule thinning. Recommendations for schedule thinning are then provided. Finally, conceptual issues related to the reemergence of problem behavior during schedule thinning and areas for future research are discussed.

Keywords: alternative activities, delay-to-reinforcement, demand fading, functional communication training, multiple schedules, punishment, response restriction schedule thinning

Functional communication training (FCT) is one of the more commonly used interventions for the treatment of problem behavior displayed by individuals with intellectual disabilities and autism (for a review, see Tiger, Hanley, & Bruzek, 2008). This differential reinforcement procedure involves teaching an individual to emit an appropriate communication response as a means of accessing a reinforcer that maintains a problem behavior (Carr & Durand, 1985). Ideally, the target communication response is not simply an alternative response that produces the maintaining reinforcer for problem behavior, but is a mand in that it is evoked by the same motivating operations (MOs) that historically evoked problem behavior. In order to achieve this desired outcome, careful attention must be taken to contrive the appropriate MOs during training (Tiger et al., 2008).

FCT has been demonstrated to be a highly effective treatment for individuals with intellectual disabilities, ranging from mild to profound, who engage in severe problem behaviors such as self-injury and aggression (e.g., Bailey, McComas, Benavides, & Lovascz, 2002; Carr & Durand, 1985; Fisher et al., 1993; Hagopian, Fisher, Sullivan, Acquisto, & LeBlanc, 1998; Kurtz, et al., 2003; Shirley, Iwata, Kahng, Mazaleski, & Lerman, 1997; Wacker et al., 1990). We searched and reviewed the published literature from 1985 to 20091 and identified 76 studies employing FCT as a treatment for 235 individuals with intellectual disabilities of varying ages (i.e., 2–34 years old) displaying a wide range of problem behavior (e.g., aggression, disruption, SIB, inappropriate sexual behavior). In the vast majority (79%) of these studies, FCT was used concurrently with extinction for problem behavior, suggesting that extinction is a critical component of FCT for the treatment of severe problem behavior (Fisher, Thompson, Hagopian, Bowman, & Krug, 2000; Hagopian et al., 1998).

Although FCT often results in rapid and clinically significant reductions in problem behavior, these outcomes may be difficult to generalize and maintain if the alternative communication response occurs at rates too high to be practically reinforced by care providers or if it occurs in situations in which it cannot be reinforced at all. Unfortunately, post-training communication response rates often approximate pretreatment rates of problem behavior (Hanley, Iwata, & Thompson, 2001). This is a potential problem because if the alternative communication response occurs at rates too high for it to be consistently reinforced, it may be weakened and eventually extinguish. Moreover, the same MOs that evoked the alternative response may evoke problem behavior when the alternative response fails to produce reinforcement. Thus, in some cases, simply establishing the alternative response and prescribing that it be reinforced immediately, at all times, and across all settings, may be neither feasible nor effective in the long run. In response, clinicians sometimes attempt to alter the schedule of reinforcement for the communication response.

Although FCT often results in rapid and clinically significant reductions in problem behavior, these outcomes may be difficult to generalize and maintain if the alternative communication response occurs at rates too high to be practically reinforced by care providers.

Schedule thinning is not an end unto itself, but a means to formally program for generalization and maintenance by exposing the individual to conditions that more closely resemble the natural environment. These efforts are generally aimed at reducing the overall rate of the alternative response, and/or bringing it under some stimulus control, all while maintaining low levels of problem behavior. It should be noted that not all the schedule alterations termed “schedule thinning” in this literature involve thinning reinforcement schedules in the strictest sense (i.e., increasing the response requirements for reinforcement). For example, when multiple schedules are used, “schedule thinning” can involve decreasing the duration of a reinforcement component while increasing the duration of an extinction component (this is discussed in detail below). Nevertheless, we will collectively term procedures that involve decreasing the overall rate or density of reinforcement for the alternative communication response reinforcement schedule thinning procedures for this review. Broadly speaking, reinforcement schedule thinning following FCT involves altering the reinforcement schedule, usually in a systematic and progressive manner across multiple sessions, until some terminal schedule, judged to be practical for care providers to implement, is reached.

In their review of FCT, Tiger et al. (2008) briefly discussed the issue of thinning reinforcement for communicative responses once those responses had been taught. We will extend Tiger et al. by describing multiple reinforcement schedule thinning procedures and supplemental treatment components to be considered following intervention with FCT and by providing practical guidelines for implementing these tactics.

Schedule Thinning Procedures

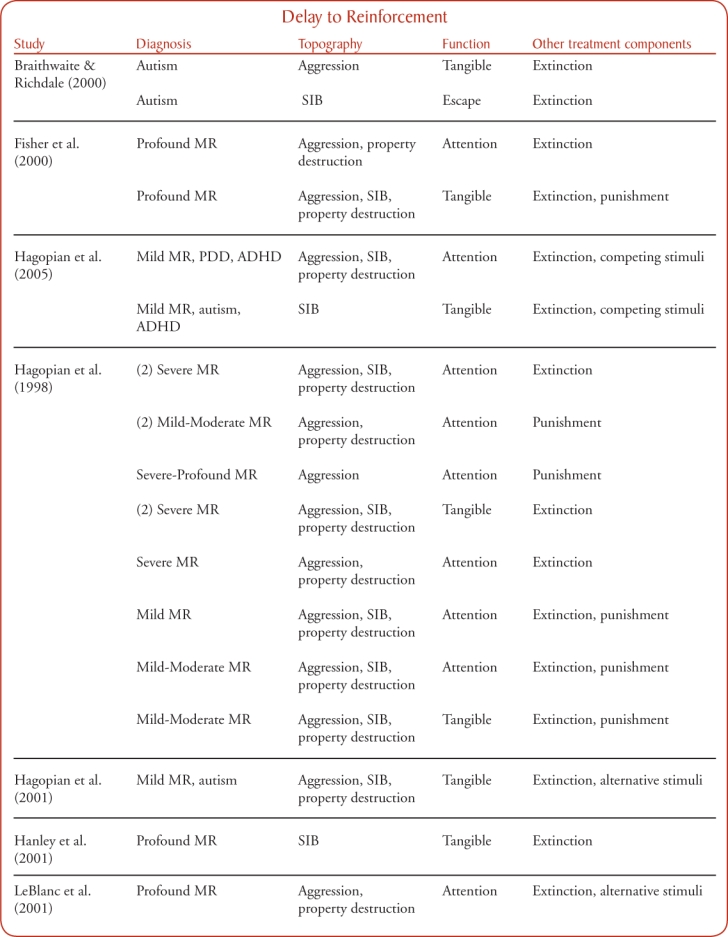

Despite the importance of programming schedule thinning within FCT, only a small proportion of studies have included a description of these sorts of procedures. Our review of 76 studies on FCT published between 1985 and 2009 revealed that only 19 studies (29%) included a description of a schedule thinning phase. In some studies, schedule thinning was not necessary because participants did not use the alternative communication response excessively or inappropriately (e.g., Durand, 1999); however, most studies that did not include schedule thinning did not comment on this issue. Of the 19 studies that included schedule thinning, a total of 52 applications1 of FCT with schedule thinning were described. Schedule arrangements employed in these studies included: (a) delay schedules, which involve introducing delays to reinforcement following the emission of the target communication response (e.g., Fisher et al., 1993); (b) chain schedules, which, in the case of escape-maintained problem behavior, involve increasing the number of demands that must be completed before requests for a break will be honored (also described as “demand fading” or “response chaining,” e.g., Lalli, Casey, & Kates, 1995); (c) multiple schedules, wherein the duration of a signaled reinforcement component is progressively decreased while the duration of a signaled extinction component is increased (e.g., Hanley et al., 2001); and (d) response restriction, which involves restricting access to the communication response (or device) for progressively longer periods of time (Roane, Fisher, Sgro, Falcomata, & Pabico, 2004). The Table provides a summary of the published studies employing these four methods of schedule thinning following FCT and each is described below.

Table.

Studies in Which Functional Communication Schedules of Reinforcement Have Been Thinned

| Study | Delay to Reinforcement | |||

| Diagnosis | Topography | Function | Other treatment components | |

|

Braithwaite & Richdale (2000) |

Autism | Aggression | Tangible | Extinction |

| Autism |

SIB |

Escape |

Extinction |

|

|

Fisher et al. (2000) |

Profound MR | Aggression, property destruction | Attention | Extinction |

| Profound MR |

Aggression, SIB, property destruction |

Tangible |

Extinction, punishment |

|

|

Hagopian et al. (2005) |

Mild MR, PDD, ADHD | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Attention | Extinction, competing stimuli |

| Mild MR, autism, ADHD |

SIB |

Tangible |

Extinction, competing stimuli |

|

|

Hagopian et al. (1998) |

(2) Severe MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Attention | Extinction |

| (2) Mild-Moderate MR | Aggression, property destruction | Attention | Punishment | |

| Severe-Profound MR | Aggression | Attention | Punishment | |

| (2) Severe MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Tangible | Extinction | |

| Severe MR | Aggression, property destruction | Attention | Extinction | |

| Mild MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Attention | Extinction, punishment | |

| Mild-Moderate MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Attention | Extinction, punishment | |

| Mild-Moderate MR |

Aggression, SIB, property destruction |

Tangible |

Extinction, punishment |

|

|

Hagopian et al. (2001) |

Mild MR, autism |

Aggression, SIB, property destruction |

Tangible |

Extinction, alternative stimuli |

|

Hanley et al. (2001) |

Profound MR |

SIB |

Tangible |

Extinction |

| LeBlanc et al. (2001) | Profound MR | Aggression, property destruction | Attention | Extinction, alternative stimuli |

| Study | Chained Schedules | |||

| Diagnosis | Topography | Function | Other treatment components | |

|

Day et al. (1994) |

Severe intellectual disability |

Aggression |

Escape |

Extinction |

|

Fisher et al. (1993) |

Profound MR |

Aggression, SIB, property destruction |

Escape |

Extinction, punishment |

|

Hagopian et al. (1998) |

Severe-Profound MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Escape | Extinction, punishment |

| Mild-Moderate MR | Aggression, property destruction | Escape | Punishment | |

| (2) Profound MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Escape | Punishment | |

| Severe MR | Aggression, property destruction | Escape | Extinction, punishment | |

| Mild MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Escape | Extinction, punishment | |

| Severe MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Escape | Extinction | |

| Mild-Moderate MR |

Aggression, SIB, property destruction |

Escape |

Punishment |

|

|

Lalli et al. (1995) |

(2) Moderate MR, autism | SIB | Escape | Extinction, prompts |

| N/A |

Aggression |

Escape |

Extinction, prompts |

|

|

Mildon et al. (2004) |

Autism |

Aggression, property destruction |

Escape |

Extinction, non-contingent escape |

|

Berg et al. (2007) |

(3) Developmental delay |

Aggression, property destruction, non-compliance |

Escape |

Extinction |

|

Peck Peterson et al. (2005) |

Developmental delay |

Elopement |

Escape |

Extinction |

| Perry & Fisher (2001) | Moderate MR, ODD | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Escape | Extinction, punishment |

| Study | Multiple Schedules | |||

| Diagnosis | Topography | Function | Other treatment components | |

|

Fisher et al. (1998) |

Mild MR | Aggression, SIB, property destruction | Tangible, attention | Extinction, alternative stimuli |

| Moderate MR, autism, ADHD |

Aggression, property destruction |

Attention |

Extinction, alternative stimuli |

|

|

Hagopian et al. (2005) |

Moderate MR, autism, ADHD |

Aggression |

Attention |

Extinction, competing stimuli |

|

Hagopian et al. (2004) |

Moderate MR, fragile X syndrome |

Aggression, SIB, property destruction |

Termination of “do” requests |

Extinction |

|

Hanley et al. (2001) |

Profound MR | SIB | Tangible | Extinction |

| Profound MR | Aggression, SIB | Tangible | Extinction | |

| Profound MR, Angelmann's Syndrome |

Aggression, SIB |

Attention |

Extinction |

|

| Jarmolowicz et al. (2009) | MR, autism | Aggression, property destruction | Tangible | Extinction |

| Study | Response Restriction | |||

| Diagnosis | Topography | Function | Other treatment components | |

|

Fyffe et al. (2004) |

Traumatic brain injury |

Inappropriate sexual behavior |

Attention |

Extinction, response blocking |

|

Hagopian et al. (2004) |

Profound MR, autism |

Aggression, SIB |

Escape |

Extinction, differential reinforcement |

| Roane et al. (2004) | Severe MR, autism | Aggression | Attention | Alternative stimuli |

| Mild MR, autism | Aggression | Tangible | Extinction | |

Delay Schedules

Description of delay schedules. In the case of FCT, delay schedules involve delaying delivery of the reinforcer following the communication response. During the initial treatment phase, when the alternative response is being established, reinforcement is typically provided immediately following the response. Once the initial therapeutic effect has been demonstrated, a brief delay is introduced between the response and the delivery of reinforcement. This delay is often signaled with a delay stimulus (e.g., verbal “wait,” or a written card containing the word “wait”). The duration of the reinforcer delay is then progressively increased across sessions.

Strengths and limitations of delay schedules. Delay schedules nicely simulate situations normally encountered in the natural environment, where reinforcement for requests is not always immediately available. One potential limitation of using delay schedules is that, as the delay is increased, the contingency between the communication response and the delivery of reinforcement may be weakened, which may result in the reemergence of problem behavior (Fisher et al., 2000; Hanley et al., 2001).

Example of delay schedules. Hagopian et al. (1998) describe typical implementation of a delay schedule. Participants were treated with FCT while on an inpatient hospital unit for the assessment and treatment of severe problem behavior. In many cases, the participants emitted the alternative response (e.g., signing for a preferred toy or attention) at such a rate that they were receiving reinforcement continuously. This made the implementation of the treatment in home and community settings impractical. Therefore, a delay was inserted between the request and the delivery of reinforcement. For example, with participants that used vocal or signed responses to request reinforcement (e.g., attention), a therapist would tell the participant “That is nice asking, but you need to wait.” No reinforcers were delivered within 2–3 seconds of these requests. This delay was then slowly increased over time (e.g., 3 s, 5 s, 10 s, etc.) until some predetermined terminal delay interval was met. The delay interval was increased only if disruptive behavior remained at low rates (e.g., 80% or greater reduction from baseline).

Use of delay schedules. Increasing delays to reinforcement following FCT is frequently used as a schedule thinning procedure. In our review, delay schedules were reported in seven studies describing 20 applications (see Table). Although there are several studies that have implemented delay schedules, in half of the applications described (10 of 20), additional treatment components were required for schedule thinning to progress (e.g., competing stimuli or punishment were added to FCT when delays were used; Fisher, et al., 2000; Hagopian, Contrucci-Kuhn, Long, & Rush, 2005; Hagopian et al., 1998; LeBlanc, Hagopian, Marhefka, & Wilke, 2001).

Table.

(continued)

Table.

(continued)

Chained Schedules or “Demand Fading”

Description of demand fading. Demand fading is typically used to thin FCT reinforcement schedules when problem behavior is maintained by escape from demands. When this is the case, FCT typically involves arranging for the alternative response to produce a brief escape or “break” from demands. Demand fading is necessary when using FCT for problem behavior maintained by escape when the individual requests escape excessively (i.e., to the extent that little or no work is completed). Demand fading involves increasing the number of demands that must be completed: (a) before the opportunity to emit the alternative response is made available (in cases where the alternative response requires access to a device) or (b) before the alternative response produces access to reinforcement. This procedure may be viewed as a chained schedule of reinforcement, wherein completion of the first link of the chain (completing a specified number of tasks) results in the onset of the terminal link of the chain (in this case, the alternative response for producing a break from demands).

Strengths and limitations of demand fading. The advantage of demand fading is that participants learn to complete instructions or other work while still accessing break opportunities through appropriate behavior. Limitations of demand fading are similar to delay schedules. That is, if requests for a break are emitted prior to meeting criteria for the response to be reinforced, the contingency between the communicative response and reinforcement (i.e., break) may be systematically weakened (Hanley et al., 2001), and problem behavior may be evoked.

Example of demand fading. Lalli et al. (1995) implemented demand fading with three individuals with intellectual disabilities (two individuals also had autism) admitted to a hospital inpatient unit for severe disruptive behavior (i.e., aggression, self-injury). First, a functional analysis demonstrated that disruptive behavior for each of the participants was maintained by negative reinforcement in the form of escape from tasks. Next, FCT was conducted to teach the participants to use an alternative response (e.g., handing over a “break” card) to gain a brief break from the task. Following FCT, demand fading was implemented by progressively increasing the number of steps, from 1 to 16, required before the alternative response resulted in access to a break. Before each task was presented, the therapist stated the criterion for earning each break. Throughout the procedure, problem behavior was placed on extinction and remained low for all individuals relative to baseline rates. If the participant was noncompliant prior to meeting the criterion for a break the therapist would physically guide the participant to complete the task. If the participant requested a break prior to the completion of the work criteria, the therapist said “good saying no, but you have to do [task step], then you can ask for a break.” Disruptive behavior decreased and remained low and the percentage of independent communication also increased as the response requirement increased during demand fading for all three participants,

Use of demand fading. In our review of FCT studies, the use of chain schedules as a means of increasing demand requirements was reported in eight studies describing 20 applications (see Table). In half of these applications (10 of 20), supplemental treatment components (e.g., noncontingent reinforcement, punishment) were used during demand fading in order to achieve targeted outcomes (Fisher et al., 1993; Hagopian et al., 1998; Mildon, Moore, & Dixon, 2004; Perry & Fisher, 2001).

Multiple Schedules

Description of multiple schedules. Multiple schedules involve the alternation of at least two distinct schedule components: reinforcement components are signaled with a discriminative stimulus when in operation (SD), and an S-Delta (SD) is present when reinforcement will not be provided (Ferster & Skinner, 1957). During the reinforcement component, the alternative response produces reinforcement (typically, for every response); whereas during the extinction component, the alternative response does not produce reinforcement. Problem behavior is typically placed on extinction during both of these schedule components.

When used following FCT as a means of thinning reinforcement schedules, multiple schedules also involve altering the relative durations of the two components. More specifically, the duration of the reinforcement component is decreased while the duration of the extinction component is increased, usually progressively across sessions. For example, in the early stages of schedule thinning, the reinforcement components may operate for a total of 9 min of a 10-min session, while the extinction component may collectively operate for a total of 1 min. In later sessions, the reinforcement component total duration may be in operation for 2 min while the extinction component duration would be in operation for 8 min (of a 10-min session).

Strengths and limitations of multiple schedules. If successful, multiple schedules can bring the alternative response under joint control of schedule-correlated stimuli and MOs relevant to problem behavior, producing a reduction of the overall rate of the alternative response while preserving the response-reinforcement contingency. One limitation is that contrived stimuli often gain stimulus control. For example, Hanley et al. (2001) used cards of different shapes to signal when each reinforcement schedule component was in effect. Ideally, rather than contrived stimuli (e.g., cards of various shapes), natural stimuli would signal which schedule component was in effect (e.g., person talking on telephone would signal that attention is not available; see below).

Example of multiple schedules. Hanley et al. (2001) directly compared the use of a multiple schedule to a mixed schedule as a means of schedule thinning following FCT, the latter of which did not have programmed stimuli correlated with each schedule component (e.g., the only difference between the schedules was the presence or absence of schedule-correlated signals). Participants were two individuals diagnosed with profound mental retardation who engaged in severe problem behavior. FCT decreased disruptive behavior, however, rates of the alternative response (requesting the reinforcer) were too high for practical implementation by care providers in a natural environment (e.g., requests for attention occurred 5 or more times per min). A multiple schedule was then implemented as a method for thinning the reinforcement schedule to make the treatment more practical for care providers to implement. During the reinforcement component, a white circular card was placed on a table next to a microswitch, which the individual pressed to request the reinforcer. During the EXT component, a red rectangular card was placed on the table next to the microswitch and all touches of the microswitch were ignored. Initially the reinforcement component was in effect the majority of the time relative to the EXT component (e.g., 45 s of reinforcement for every 15 s of EXT). The duration of the EXT component was gradually increased while the duration of the reinforcement component was gradually decreased. For both participants, the multiple schedule was more effective at reducing rates of problem behavior and, relative to the mixed schedule, showed better schedule control over the alternative response such that touching the microswitch occurred most often when the reinforcement schedule was in effect. These results suggest that the stimuli associated with each component (i.e., white circle, red rectangle) functioned as discriminative stimuli. Subsequent studies have shown that similar stimulus control can be established even when only one component schedule is signaled (Fisher, Kuhn, & Thompson, 1998; Jarmolowicz, DeLeon, & Contrucci-Kuhn, 2009).

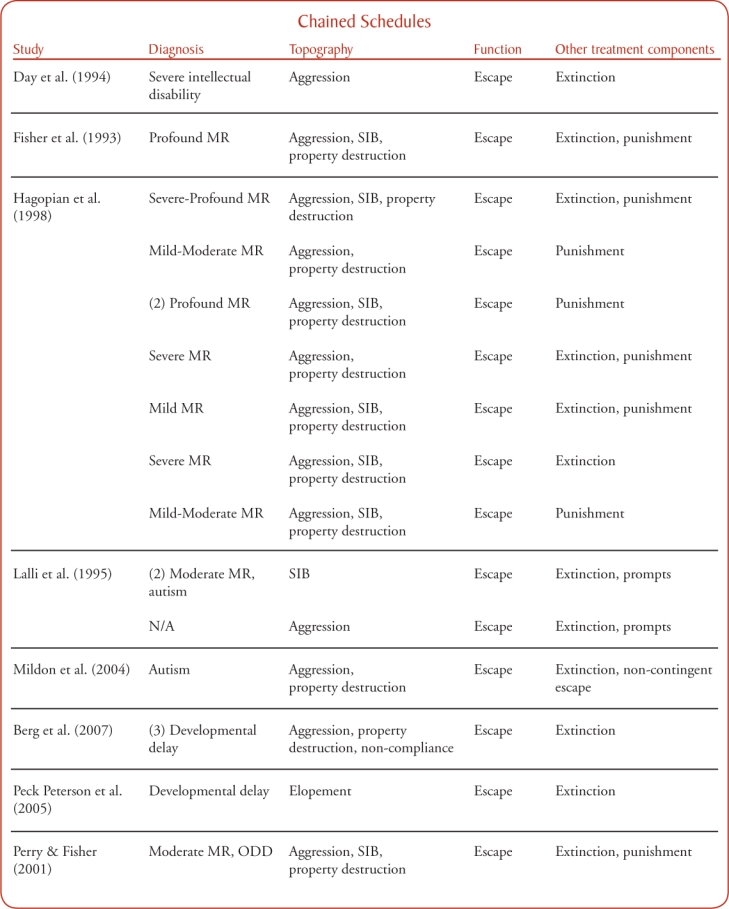

Use of multiple schedules. In our review, we found five studies describing eight applications of FCT that used multiple schedules as a means of thinning reinforcement schedules and maintaining low rates of problem behavior (see Table). In some of the applications (5 of 8), the use of multiple schedules resulted in the successful achievement of treatment goals with FCT and extinction without supplemental treatment components (Hagopian, Toole, Long, Bowman, & Lieving, 2004; Hanley et al., 2001; Jarmolowicz et al., 2009). However similar to the previous two schedule-thinning methods, for some applications (3 of 8), treatment goals were not met until supplemental components were added (e.g., adding competing or alternative stimuli; Fisher et al., 1998; Hagopian et al., 2005). Overall, these outcomes suggest that employing multiple schedules is a generally effective strategy for reinforcement schedule thinning following FCT.

Response Restriction

Description of response restriction. Response restriction entails restricting access to a device needed to engage in the alternative response. Restricting the response prevents it from being emitted too frequently. This procedure is only applicable when the alternative response requires a device that can be restricted (e.g., activation of a microswitch or exchanging a picture card).

Strengths and limitations of response restriction. The advantage to the response restriction procedure is that the response-reinforcement contingency remains intact because there is little to no opportunity to emit the alternative response when it will not be reinforced. Alternatively, one could view this as a potential disadvantage because it limits opportunities for the alternative response to contact delayed or non-reinforcement. Each time the device is made available, responding on the device is reinforced. Thus, over time the presentation of the device itself can become discriminative for the emission of the appropriate response. Another limitation of response restriction is that it may not be appropriate for individuals who use an augmentative communication device as a comprehensive system used for their primary means of communication.

Example of response restriction. Roane et al. (2004) used a response restriction procedure with two children with autism and intellectual disabilities who engaged in aggressive behavior. In this study, functional analyses showed that aggression was maintained by positive reinforcement for both children (access to attention and preferred items, respectively). FCT was then implemented, and handing a communication card to the therapist was reinforced instead of aggression. Access to the communication card was initially available throughout the entire treatment session, and the rate at which the children were requesting positive reinforcement was too high for the treatment to be sustained in the natural environment (e.g., requests occurred more than twice a minute). During response restriction, access to the communication cards was restricted for a brief time. The restriction interval was gradually increased if aggression remained low. For example, with one participant, treatment sessions were 10 min long and the initial restriction interval was 3 s, which was increased to 5 s in a subsequent session. Across subsequent sessions the interval was doubled if aggression remained low until the restriction interval reached 320 s.

Use of response restriction. In our review, response restriction as a means of schedule thinning following FCT was reported in three studies describing four applications (see Table). Targeted outcomes were achieved for one of the four applications without the use of supplemental components beyond extinction (Roane et al., 2004). In three of the four applications, supplemental components (e.g., noncontingent reinforcement, response blocking) were included to achieve treatment goals.

Pacing of Reinforcement Schedule Thinning

The various schedule arrangements described above outline the procedures used to thin reinforcement schedules after FCT. Other considerations, however, such as the pace and magnitude of schedule changes toward the terminal schedule also warrant discussion. To date, few studies have systematically manipulated these parameters related to the progression of schedule thinning following FCT (or other interventions for that matter). Consequently, there is little uniformity across studies regarding the selection of the terminal schedule, the criteria for advancing and retreating during schedule thinning, and the magnitude of changes in schedule values. The literature, however, does provide some guidance on how to progress toward the terminal schedule.

Setting A-Priori Criteria

In some studies, a terminal schedule is defined a priori; often based on an informal clinical appraisal about what schedule might be sustainable in the natural environment (e.g., a multiple schedule with a 4 min extinction component and 1 min reinforcement component). These studies typically advance toward the terminal schedule by setting a criterion for the amount of problem behavior allowable during treatment before advancing to the next step (e.g., 85% or greater reduction from baseline) and then slowly thinning the schedule by progressively increasing the duration of the extinction component (e.g., 15 s, 30 s, 45 s, etc.) if the problem behavior remains below the set criterion (e.g., Hanley et al., 2001; Hagopian et al., 2005; Jarmolowicz et al., 2009). If problem behavior increases above the criterion when thinning schedules of reinforcement, progression toward the terminal schedule is usually stopped or reversed until problem behavior decreases (e.g., Hagopian et al., 2005).

Probing Leaner Schedules

An alternative method of thinning schedules to a clinically acceptable terminal arrangement is the use of a probe design (LeBlanc et al., 2001). This procedure involves first establishing a sequence of progressively leaner schedules or “steps” defining the full range of intermediate schedule values from the initial schedule to the terminal schedule. Probe sessions using schedule values that are three steps beyond the current one are conducted (e.g., probing at the 6th step after successfully completing the 3rd step). If problem behavior remains low, another probe advancing three more steps in the progression is conducted (e.g., probing from the 6th to the 9th step), and so on until the terminal goal is reached. However, if problem behavior increases during a probe session, the schedule is returned to the last successful step in the established progression and the intermediate steps are conducted. The process of probing forward in this manner is continued until the terminal goal is reached. These probes are conducted to determine if all the steps in the established sequence are required, or whether schedule thinning can proceed more quickly while maintaining the desired levels of problem behavior. LeBlanc and colleagues suggest this probe procedure may allow for an accelerated rate of schedule thinning while maintaining low rates of problem behavior; however the efficacy of this method has only limited support (i.e., used in two applications: LeBlanc et al., 2001; Hagopian et al., 2005).

Abruptly Shifting to the Terminal Schedule

Abruptly altering schedules directly to the terminal arrangement (as opposed to graduated changes) also may be effective in some cases. Hagopian et al. (2004) compared the effects of progressive schedule thinning (similar to that described above) to an abrupt shift to the terminal schedule. For one of two cases, the clinical goal was attained more rapidly in the abruptly shifting condition than in the progressive thinning condition. In the other case, the difference was marginal. One major disadvantage of the abruptly shifting condition, however, was that problem behavior increased to levels higher than baseline rates (characteristic of an extinction effect) during the initial sessions. Thus, abruptly shifting from dense to lean schedules may be effective in some cases, but may not be a safe option for individuals with more severe problem behavior in which an extinction-induced increase in behavior might be harmful.

One potential limitation of using delay schedules is that, as the delay is increased, the contingency between the communication response and the delivery of reinforcement may be weakened, which may result in the reemergence of problem behavior.

Supplemental Treatment Components

Although reinforcement schedule thinning is undertaken in an attempt to enhance the long-term efficacy of FCT, implementing such schedule alterations are often associated with the reemergence or escalation of problem behavior—at least in the short run (Fisher et al., 2000; Hagopian et al., 1998; Hanley et al., 2001). Understanding why problem behavior reemerges during schedule thinning is important for thinning schedules following FCT.

Hagopian et al. (2004) suggested that problem behavior may not be sufficiently extinguished in the early stages of FCT (prior to schedule thinning) because immediate near-zero levels of problem behavior may occur with FCT. It is also possible that in establishing an alternative communication response that is functionally equivalent to problem behavior (prior to extinguishing problem behavior), the alternative response and problem behavior may become members of the same functional response class (Hagopian et al., 1998). Thus, as the dense schedule of reinforcement for the alternative response is degraded during schedule thinning, the EO for the reinforcer strengthens, and responding is once again allocated toward problem behavior—which had only limited contact with extinction and never extinguished, and in fact, may have been partially maintained through the reinforcement of the other member of the response class. As a result, problem behavior may not fully contact extinction until schedule thinning is well underway. Findings from an analysis comparing progressive schedule thinning relative to an abrupt change to the terminal schedule provide some support for this account (Hagopian et al., 2004).

Alternatively, the reemergence of problem behavior during FCT schedule thinning may occur as a function of a process such as resurgence. Resurgence has been defined as the recurrence of previously extinguished operants when another operant in the same class is placed on extinction (Epstein, 1983; Lieving & Lattal, 2003). Lieving, Hagopian, Long, and O'Connor (2004) found that resurgence occurred for problem behaviors recently extinguished when other topographies of problem behaviors within the same functional response class were subsequently placed on extinction. A similar phenomenon may occur when the schedule of reinforcement for an alternative communicative response is thinned and an extinction-like condition for that response occurs. In contrast to the earlier hypothesis that problem behavior may not encounter extinction until schedule thinning occurs, this account assumes problem behavior was previously extinguished and then “resurges” during schedule thinning.

Supplemental treatment components beyond extinction added to FCT during schedule thinning described in the literature include: returning to a denser schedule, access to alternative activities (Fisher et al., 2000) or competing stimuli (Hagopian et al., 2005), and response reduction procedures (Fisher et al., 1993). It should be noted that, it is sometimes necessary to include supplemental treatment components when FCT fails to produce sufficient reductions in problem behavior (even before schedule thinning, see Hanley, Piazza, Fisher, & Maglieri, 2005).

Return to Denser Schedule

The most obvious and frequently employed approach to addressing the escalation of problem behavior involves returning to the schedule value most recently associated with low levels of problem behavior. After problem behavior returns to lower levels, progression toward the terminal schedule can be resumed (e.g., Hagopian et al., 2004). However, increases in problem behavior and disruptions in the alternative response may persist such that the schedule cannot be thinned to the terminal goal. In these cases, other supplemental treatment components may be needed in order to achieve desirable clinical outcomes.

Noncontingent Access to Alternative or Competing Stimuli

Providing individuals with alternative stimuli during delays to reinforcement has been shown to reduce problem behavior associated with schedule thinning using delay schedules (Fisher et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 2000). Fisher et al. (2000) successfully reduced the tangibly-maintained severe problem behavior of an individual diagnosed with profound mental retardation with FCT. Rates of problem behavior increased, however, when a brief delay to reinforcement was introduced. The individual was then prompted to engage in a preferred work activity during the delay interval. This procedure produced sustained decreases in problem behavior and allowed the delay interval to be increased to 10 min. Thus, the intervention was more practical for use in natural environments where delays to reinforcement were sometimes unavoidable. These investigators suggested that the work activity might have functioned as a distracter or provided some type of alternative reinforcement.

If problem behavior begins to increase during schedule thinning, first determine whether the benefits of a lean reinforcement schedule justify the additional effort associated with including additional treatment components.

Hagopian et al. (2005) extended this method by empirically identifying stimuli that were shown to compete with the reinforcer maintaining problem behavior. A competing stimulus assessment (CSA) was conducted to identify stimuli that were associated with lower levels of problem behavior even when problem behavior produced reinforcement (stimuli producing such effects are characterized as competing stimuli, because they are presumed to compete with the reinforcement maintaining problem behavior). The investigators directly compared the use of FCT with and without the use of competing stimuli during delay schedule thinning across three individuals with intellectual disabilities. Providing access to competing stimuli during FCT allowed schedule thinning to proceed more rapidly, while maintaining lower levels of problem behavior and communicative responding relative to when such stimuli were not available. The use of alternative or competing stimuli during FCT has been described in several studies (Fisher et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 2000; Hagopian et al., 2005; Hagopian, Wilson, & Wilder, 2001; LeBlanc et al., 2001; Roane et al., 2004) all of which resulted in low rates of problem behavior and allowed schedule thinning to progress.

Response Reduction Procedures

Response reduction procedures (e.g., punishment) have been used as an additional treatment component in conjunction with FCT to decrease rates of problem behavior and allow schedule thinning to progress. Fisher et al. (1993) investigated the use of FCT with and without punishment procedures with three individuals diagnosed with profound mental retardation who engaged in severe problem behavior requiring hospitalization. Results showed that FCT was not sufficient to maintain low rates of problem behaviors for any of the three individuals. However, when punishment (e.g., work tasks, brief manual restraint) was added, problem behavior decreased to low rates that were maintained for two of the three participants and schedule thinning was successfully conducted.

In a larger scale study, Hagopian et al. (1998) reported 27 applications of FCT. FCT with extinction effectively reduced problem behavior by 90% or more in 11 of 25 applications (44%). However, when schedule thinning was conducted, problem behavior increased in over half of the applications (a 90% or greater reduction occurred in 5 of 12 applications; 42%). FCT with punishment was evaluated in 17 applications producing a successful outcome in 100% of applications. In the 13 of the applications employing FCT with punishment, schedule thinning was conducted successfully (i.e., at least a 90% reduction of problem behavior maintained). These general findings are consistent with findings obtained in other studies showing the improved efficacy of FCT with punishment (Fisher et al., 1993; Fisher et al., 2000; Wacker et al., 1990); however, it should be noted that these studies included participants with highly severe and treatment resistant problem behavior, most of which required inpatient hospitalization.

Recommendations

What Schedule Thinning Procedure Should You Use?

Review of the literature describing schedule thinning following FCT reveals the primary challenge to be the reemergence of problem behavior. Of the various schedule arrangements that have been described in the literature and reviewed in this paper, multiple schedules and delay schedules have the strongest support; and in the case of negative reinforcement, chain schedules (or “demand fading”) appear generally effective. Although delay schedules have been shown to be generally effective at achieving brief delays to positive reinforcement, the use of this schedule alone is not often effective for maintaining low levels of problem behavior with long delays to reinforcement. Thus, we suggest that this schedule thinning procedure be used when only brief delays (e.g., 15 to 30 s) are desired. If longer delays (e.g., 1 min or more) are the goal, delay schedules may need to be augmented with additional components (e.g., competing stimuli) to decrease the likelihood of problem behavior. Multiple schedules are the alternative to delay schedules when there is a need to have relatively long periods in which positive reinforcement will not be available (Hagopian et al., 2005; Hanley et al., 2001; Tiger et al., 2008). In the case of negative reinforcement (e.g., FCT for escape-maintained problem behavior), chain schedules are recommended (Lalli et al., 1995). The response restriction procedure has also shown promise, however, this procedure is restricted to forms of mands that require a communication device and may not be appropriate in cases in which that device serves as the individual's primary mode of communication.

What Should You Do if Low Levels of Problem Behavior Cannot Be Maintained During Schedule Thinning?

If problem behavior begins to increase during schedule thinning, first determine whether the benefits of a lean reinforcement schedule justify the additional effort associated with including additional treatment components. If the communication response is occurring at high rates, to the extent that there is concern that the treatment will ultimately fail, then the addition of alternative stimuli or competing stimuli may be indicated (Fisher et al., 2000; Hagopian et al., 2005; Roane et al., 2004). In cases with more severe behavior (e.g., behavior that is potentially dangerous) and if other interventions have not been successful, response reduction procedures should be considered. For example, the addition of punishment to FCT during schedule thinning has resulted in successful outcomes in the majority (94%) of applications in the published literature (Fisher et al., 1993; Fisher et al., 2000; Hagopian et al., 1998; Perry & Fisher, 2001).

How Should You Progress With Schedule Thinning When Using a Specific Thinning Procedure?

In light of the limited amount of research on the progression of schedule thinning following FCT, recommendations are difficult to offer in this regard. If problem behavior is relatively benign, such that an extinction burst could be tolerated, it may be more time efficient to immediately implement the terminal schedule (Hagopian et al., 2004). However, this procedure may initially evoke rates of problem behavior above baseline. Therefore if the behavior is severe (e.g., self-injury), smaller shifts in the schedule may be a safer option. When possible, consider probing to leaner schedules by skipping intermediate steps in the thinning procedure. Using such probes may allow you to achieve the terminal schedule sooner (LeBlanc et al., 2001).

Are There Other Ways to Reduce High Rates of Communication Besides Schedule Thinning?

Given the challenges of thinning schedules of reinforcement following FCT, it may be desirable to identify other ways to make FCT practical to implement under typical conditions. One approach recently described involves bringing the communication response under control of naturally occurring stimuli that signal the availability of reinforcement (Kuhn, Chirighin, & Zelenka, 2010; Leon, Hausman, Kahng, & Becraft, 2010). In these studies, a multiple schedule arrangement was used wherein therapist behavior signaling he/she was “busy” (e.g., talking on the phone) was correlated with extinction for the communication response, while therapist behavior signaling he/she was “not busy” (e.g., sitting in a chair) was correlated with reinforcement for the communication response. The reinforcement and extinction component durations were held constant. In one case, the individual was also taught to ask if the adult was busy prior to asking for attention. The rationale for bringing the communication response under control of these naturally occurring stimuli is that it should result in the communication response being emitted at times when caregivers are more able/likely to reinforce it, and decrease the emission of the communication response at times when reinforcement is less likely.

Motivating operations (MOs) should also be considered when schedule thinning following FCT. Brown et al. (2000) demonstrated that delivering the functional reinforcer non-contingently (which ostensibly altered the EO) decreased both rates of communication and problem behavior maintained by the same reinforcer (i.e., same response class; see also Goh, Iwata, & DeLeon, 2000). Providing noncontingent access to “arbitrary” reinforcement (i.e., reinforcers other than those responsible for maintaining problem behavior) has been suggested as a possible method to facilitate schedule thinning (Hanley et al., 2001). As noted previously, there is evidence indicating that relative to FCT alone, supplementing FCT with noncontingent reinforcement using preferred (Fisher et al., 2000) or competing stimuli (Hagopian et al., 2005) can facilitate schedule thinning. Finally, given that the MO-altering effects of free access to reinforcement extends beyond their concurrent availability (Vollmer & Iwata, 1991), there may be some benefits to providing noncontingent reinforcement in advance of periods in which one can anticipate that the functional reinforcer may be less accessible.

Conclusions

Treatments such as FCT that decrease problem behavior while simultaneously establishing an appropriate replacement behavior have obvious appeal. However, simply establishing an alternative response may not be sufficient in many cases. In particular, when the communication response occurs at rates that are too high to be consistently reinforced, additional intervention may be needed. The literature on reinforcement schedule thinning following FCT describes a range of tactics designed to make this intervention more sustainable in the long run. Three broad conclusions may be drawn based on the current review. First, minor programmed reductions in reinforcer density (for the alternative communication response) often result in the reemergence of problem behavior, supporting the notion that it is advisable to continue with treatment until the communication response occurs at rates that can be supported in the natural environment. Second, reinforcement schedule thinning can be effective in decreasing the rate of the communication response while maintaining low levels of problem behavior. Third, given the challenges with schedule thinning following FCT, attention should also be focused on identifying supplemental techniques to enhance the sustainability of FCT beyond schedule thinning (Hanley et al., 2001). Recent research suggests that attenuating the EOs for the communication response (and problem behavior) by providing alternative reinforcers can facilitate schedule thinning (Fisher et al., 1998; Hagopian et al., 2005). Also, interventions aimed at bringing the communication response under discriminative control of naturally occurring stimuli that are correlated with the probability of reinforcement show great promise (Kuhn et al., 2010, Leon et al., 2010).

Footnotes

1Articles were initially located by reviewing published studies listed in the PsychLit and PubMed databases between January 1985 to October 2009. Two search terms, one from each category, were always combined and each term was combined with every other term in the other category. The terms were as follows: (1) functional communication training; (2) functional communication; and (3) alternative communication. Following this initial step, the abstracts of the articles meeting the above criteria were reviewed to determine if the authors had implemented FCT as a treatment for aggression, self-injury, or property destruction (referred to in this manuscript collectively as “problem behavior”).

1Note: The term application is used to refers to a single treatment evaluation of FCT. The term case is not used because there are studies that report on cases in which FCT was applied more than once for that individual (i.e., once for escape-maintained behavior, and once for attention-maintained behavior).

Action Editor: Michael Himle

References

- Bailey J, McComas J. J, Benavides C, Lovascz C. Functional assessment in a residential setting: Identifying an effective communicative replacement response for aggressive behavior. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2002;14:353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Berg W. K, Wacker D. P, Harding J. W, Ganzer J, Barretto A. An evaluation of multiple dependent variables across distinct classes of antecedent stimuli pre and post functional communication training. Journal of Education and Intensive Behavioral Intervention. 2007;3:305–333. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite K. L, Richdale A. L. Functional communication training to replace challenging behaviors across two behavioral outcomes. Behavioral Interventions. 2000;15:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. A, Wacker D. P, Derby K. M, Peck S. M, Richman D. M, Sasso G. M, Harding J. W. Evaluating the effects of functional communication training in the presence and absence of establishing operations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:53–71. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr E. G, Durand V. M. Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:111–126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day H. M, Horner R. H, O'Neill R. E. Multiple functions of problem behaviors: Assessment and intervention. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:279–289. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand V. M. Functional communication training using assistive devices: Recruiting natural communities of reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:247–267. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R. Resurgence of previously reinforced behavior during extinction. Behaviour Analysis Letters. 1983;3:391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ferster C. B, Skinner B. F. Schedules of reinforcement. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W. W, Kuhn D. E, Thompson R. H. Establishing discriminative control of responding using functional and alternative reinforcers during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:543–560. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W. W, Piazza C, Cataldo M, Harrell R, Jefferson G, Conner R. Functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:23–36. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W. W, Thompson R. H, Hagopian L, Bowman L. G, Krug A. Facilitating tolerance of delayed reinforcement during functional communication training. Behavior Modifications. 2000;24:3–29. doi: 10.1177/0145445500241001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyffe C. E, Kahng S. W, Frittro E, Russell D. Functional analysis and treatment of inappropriate sexual behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:401–404. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh H, Iwata B. A, DeLeon I. G. Competition between noncontingent and contingent reinforcement schedules during response acquisition. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:195–205. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Contrucci-Kuhn S. A, Long E. S, Rush K. S. Schedule thinning following communication training: Using competing stimuli to enhance tolerance to decrements in reinforcer density. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:177–193. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.43-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Fisher W. W, Sullivan M. T, Acquisto J, LeBlanc L. A. Effectiveness of functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment: A summary of 21 inpatient cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:211–235. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Toole L. M, Long E. S, Bowman L. G, Lieving G. A. A comparison of dense-to-lean and fixed lean schedules of alternative reinforcement and extinction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:323–337. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Wilson D. M, Wilder D. A. Assessment and treatment of problem behavior maintained by escape from attention and access to tangible items. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:229–232. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G. P, Iwata B. A, Thompson R. H. Reinforcement schedule thinning following treatment with functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;4:17–38. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G. P, Piazza C. C, Fisher W. W, Maglieri K. M. On the effectiveness of and preference for punishment and extinction components of function-based interventions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:51–66. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.6-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz D. P, DeLeon I. G, Contrucci-Kuhn S. A. Functional Communication during Signaled Reinforcement and/or Extinction. Behavioral Interventions. 2009;24:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D.E, Chirighin A.E, Zelenka K. Discriminated functional communication: A procedural extension of functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:249–264. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz P. F, Chin M. D, Huete J. M, Tarbox R. S. F, O'Connor J. T, Paclawskyj T. R, Rush K. S. Functional analysis and treatment of self-injurious behavior in young children: A summary of 30 cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:205–219. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli J. S, Casey S, Kates K. Reducing escape behavior and increasing task completion with functional communication training, extinction, and response chaining. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:261–268. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc L. A, Hagopian L. P, Marhefka J. M, Wilke A. E. Effects of therapist gender and type of attention on assessment and treatment of attention-maintained destructive behavior. Behavioral Interventions. 2001;16:39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Leon Y, Hausman N. L, Kahng S, Becraft J. L. Further examination of discriminated functional communication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:525–530. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieving G. A, Hagopian L. P, Long E. S, O'Connor J. Response-class hierarchies and resurgence of severe problem behavior. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:621–634. [Google Scholar]

- Lieving G. A, Lattal K. A. Recency, repeatability, and reinforcer retrenchment: An experimental analysis of resurgence. Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2003;80:217–233. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2003.80-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mildon R. L, Moore D. W, Dixon R. S. Combining noncontingent escape and functional communication training as a treatment for negatively reinforced disruptive behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2004;6:92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Peck Peterson S. M, Caniglia C, Royster A. J, Macfarlane E, Plowman K, Baird S. J, Wu N. Blending functional communication training and choice making to improve task engagement and decrease problem behaviour. Educational Psychology. 2005;25:257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Perry A. C, Fisher W. W. Behavioral Economics Influences on Treatments Designed to Decrease Destructive Behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:211–215. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roane H. S, Fisher W. W, Sgro G. M, Falcomata T. S, Pabico R. R. An alternative method of thinning reinforcer delivery during differential reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:213–218. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley M. J, Iwata B. A, Kahng S, Mazaleski J. L, Lerman D. C. Does functional communication training compete with ongoing contingencies of reinforcement? An analysis during response acquisition and maintenance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:93–104. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiger J. H, Hanley G. P, Bruzek J. Functional communication training: A review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1:16–23. doi: 10.1007/BF03391716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T. R, Iwata B. A. Establishing operations and reinforcement effects. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:279–291. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker D. P, Berg W. K, Harding J. W, Barretto A, Rankin B, Ganzer J. Treatment effectiveness, stimulus generalization, and acceptability to parents of functional communication training. Educational Psychology. 2005;25:233–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wacker D. P, Steege M. W, Northup J, Sasso G, Berg W, Reimers T, Donn L. A component analysis of functional communication training across three topographies of severe behavior problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:417–429. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]