Abstract

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) transfers cholesteryl ester (CE) and triglyceride between HDL and apoB-containing lipoproteins. Anacetrapib (ANA), a reversible inhibitor of CETP, raises HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) and lowers LDL cholesterol in dyslipidemic patients; however, the effects of ANA on cholesterol/lipoprotein metabolism in a dyslipidemic hamster model have not been demonstrated. To test whether ANA (60mg/kg/day, 2 weeks) promoted reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), 3H-cholesterol-loaded macrophages were injected and 3H-tracer levels were measured in HDL, liver, and feces. Compared to controls, ANA inhibited CETP (94%) and increased HDL-C (47%). 3H-tracer in HDL increased by 69% in hamsters treated with ANA, suggesting increased cholesterol efflux from macrophages to HDL. 3H-tracer in fecal cholesterol and bile acids increased by 90% and 57%, respectively, indicating increased macrophage-to-feces RCT. Mass spectrometry analysis of HDL from ANA-treated hamsters revealed an increase in free unlabeled cholesterol and CE. Furthermore, bulk cholesterol and cholic acid were increased in feces from ANA-treated hamsters. Using two independent approaches to assess cholesterol metabolism, the current study demonstrates that CETP inhibition with ANA promotes macrophage-to-feces RCT and results in increased fecal cholesterol/bile acid excretion, further supporting its development as a novel lipid therapy for the treatment of dyslipidemia and atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Keywords: cholesteryl ester transfer protein, cholesterol efflux, high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein

Cardiovascular disease continues to be a major contributor to morbidity and mortality throughout the world. Despite therapies such as statins, which reduce circulating levels of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), cardiovascular event rates remain high. Numerous epidemiological studies (e.g., the Framingham Heart Study) indicate that high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels are inversely correlated with cardiovascular risk (1–6). Therefore, therapies that increase HDL-C have gained recent attention as possible treatments for dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis.

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) mediates transfer of cholesteryl ester (CE) and triglyceride (TG) between HDL and apoB-containing lipoproteins such as LDL and therefore, represents an attractive target for increasing HDL-C and reducing LDL-C. Indeed, initial clinical trials with torcetrapib established the validity of CETP inhibition as a mechanism for elevation of HDL-C (7, 8). However, the phase III outcome trial ILLUMINATE demonstrated that torcetrapib treatment was associated with an increase in cardiovascular events and overall mortality, possibly due to off-target effects on blood pressure and circulating adrenal hormones (9). A series of preclinical studies further corroborated that torcetrapib had compound-specific off-target activity that was unrelated to CETP inhibition (10–12).

Anacetrapib (ANA) is a potent CETP inhibitor that has not demonstrated the off-target activities of torcetrapib in preclinical or clinical studies (10, 13–15). ANA treatment increases HDL-C by over 100% and lowers LDL-C by 30–40% as a monotherapy and when coadministered with statins (13–15). In a recent 1.5 year safety study in ∼1,600 patients with cardiovascular disease (15), ANA treatment had no effect on blood pressure, electrolytes, or aldosterone, and the distribution of cardiovascular events suggested that ANA treatment would not be associated with an increase of cardiovascular risk that was observed with torcetrapib.

In order to comprehensively understand the impact of the robust changes in lipoprotein-associated cholesterol and cholesterol homeostasis induced by ANA, multiple approaches must be used. Macrophage-to-feces reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) is widely studied in mice to examine pathways that affect the egress of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the feces (16). However, because mice do not inherently express CETP, mouse models are of little use without transgenic overexpression. The Syrian golden hamster expresses CETP endogenously and both normolipidemic and dyslipidemic versions of this model have been used to study RCT in response to lipid-modifying therapies (for review, see Ref. 17), in most cases using the approach described by Rader and Rothblat (16–21). Further, a comprehensive analysis of lipid metabolism including the study of RCT and monitoring lipoprotein lipid composition and bulk cholesterol and bile acid excretion is critical to more completely understand the effects of CETP inhibition on how lipoproteins handle or “traffic” cholesterol. The information gleaned from comprehensive profiling of lipoprotein metabolism and cholesterol trafficking in response to anacetrapib treatment will inform the CETP field on the mechanisms by which CETP inhibition with anacetrapib might prove beneficial in the clinic. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that CETP inhibition with ANA will promote macrophage-to-feces RCT and cholesterol excretion in a dyslipidemic hamster model.

METHODS

Animals

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Merck Research Laboratories Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Rahway, NJ). Male Syrian golden hamsters (weight ∼100 g at beginning of study) were given free access to food and water. For tracer-based RCT/fractional catabolic rate (FCR) experiments and for bulk cholesterol experiments, hamsters were placed on a high-fat diet [45% kcal from fat (lard), 35% kcal from carbohydrate, 20% kcal from protein, 0.12% cholesterol; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ]. This diet was chosen based upon pilot studies, which determined that this level of dietary cholesterol would produce dyslipidemia relative to normal hamster diet without inducing liver steatosis. After 4 weeks of induction of dyslipidemia, hamsters were maintained on the high-fat diet and administered ANA, admixed into the diet to deliver 60 mg/kg, or control high-fat diet (no ANA). Prior to treatment, blood samples were taken for pretreatment biochemical analysis (see below). The dose of ANA was identified in pilot dose-ranging studies that indicated this dose produced maximal inhibition of CETP and maximal changes in lipoproteins (e.g., increase in HDL-C; data not shown). Animals were treated with ANA for 2 weeks. Plasma ANA concentrations were determined by standardized LC/MS methods by the Merck Research Laboratories Drug Metabolism/Pharmacokinetic department.

RCT and FCR studies

Experiments studying RCT and FCR of HDL were performed at Physiogenex (Labege, France). For these studies, each treatment group (control, ANA) was divided into two groups of 12 animals; one for RCT studies and one for FCR experiments. Animals were maintained on the same diet and treatment regimen during the RCT and FCR procedures.

Biochemical analysis.

For RCT and FCR studies, total cholesterol (TC) and TGs were assayed using commercial kits (Biomerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). HDL-C was determined using the phosphotungstate/ MgCl2 precipitation method. NonHDL-C levels were then determined by subtracting HDL-C values from total plasma cholesterol. Plasma CETP activity was measured by fluorescence using commercial kits (Roarbiomedical, New York, NY).

In vivo macrophage-to-feces RCT.

Preparation of J774 cells and in vivo RCT study were performed as previously described (22). J774 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA), were grown in suspension in RPMI/HEPES supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.5% gentamicin in suspension in Nalgene Teflon flasks. Cells were radiolabeled with 5 µCi/ml 3H-cholesterol and cholesterol loaded with 50 µg/ml oxidized LDL over 48 h. Radiolabeled cells were then washed with RPMI/HEPES and equilibrated for 4 h in fresh RPMI/HEPES supplemented with 0.2% BSA and gentamicin. Cells were pelleted by low speed centrifugation and resuspended in MEM/HEPES prior to injection into hamsters.

Following 2 weeks of ANA treatment (described above), 3H-cholesterol-labeled and oxidized LDL-loaded J774 cells (2.5 × 106 cells containing 10 × 106 dpm in 0.5 ml minimum essential medium) were injected intraperitoneally into individually caged hamsters. Animals had free access to food and water and were maintained on diet and treatment during the 72 h experiment. Blood was collected by from the jugular vein under isoflurane anesthesia at 24, 48, and 72 h to measure radioactivity released into the plasma and HDL after phosphotungstate/MgCl2 precipitation (50 µL of plasma or HDL counted). Hamsters were then euthanized by cervical dislocation, exsanguinated, and the liver was harvested from each animal. For total liver 3H-tracer determination, a 50 mg piece of liver was homogenized using an ultrasound probe in 500 µL water then 100 µL were counted in a liquid scintillation counter. Liver and fecal 3H-labeled cholesterol and bile acids were determined as described (21). Briefly, for 3H-cholesterol and 3H-bile acid determination from liver, a 50 mg piece of liver was homogenized in 0.5 ml distilled water. To extract the 3H-cholesterol and 3H-bile acid fractions, each homogenized sample was combined with 1 ml ethanol and 200 µL NaOH. The samples were saponified at 95°C for 1 h and cooled to room temperature, and then 3H-cholesterol was extracted two times with 3 ml hexane. The extracts were pooled, evaporated, resuspended in toluene, and then counted in a liquid scintillation counter. To extract 3H-bile acids, the remaining aqueous portion of the feces was acidified with concentrated HCl and then extracted two times with 3 ml ethyl acetate. The extracts were pooled together, evaporated, resuspended in ethyl acetate, and counted in a liquid scintillation counter. Feces were collected over 72 h and were stored at 4°C before extraction of cholesterol and bile acids. Fecal 3H-cholesterol and 3H-bile acids were measured as described above for liver, with the exception that 1 ml of distilled water was used per 100 mg of feces for homogenization. Results were expressed as a percent of the radioactivity injected recovered in plasma, HDL, liver, and feces. The plasma volume was estimated as 3.5% of the body weight.

In vivo 3H-cholesteryl oleate-HDL kinetics (FCR).

A plasma pool was obtained from normocholesterolemic hamsters maintained on a control diet. Hamster HDLs (d = 1.07–1.21) were then isolated by ultracentrifugation as previously described (22). After extensive dialysis against saline, HDL was labeled with 3H-cholesteryl oleate in the presence of lipoprotein-deficient serum collected from rabbit plasma. The labeled HDLs were reisolated by ultracentrifugation (d = 1.07–1.21) then extensively dialyzed prior to injection.

The day before the in vivo experiment, a catheter was inserted into the jugular vein under isoflurane anesthesia for both injection and blood collection. Catheters were kept with NaCl 0.9%. To prevent blood circulation and coagulation inside the catheter, a small volume of heparin (500 IU/ml) and glycerol (1 g/ml) was injected at the catheter extremity.

The day of the experiment, hamsters were weighed and placed into individual cages. Animals had free access to food and water and were kept treated over the 48 h experiment. The 3H-cholesteryl oleate-labeled HDLs (∼ 2–3 million dpm) were injected intravenously and blood samples (150 µL) were collected at time t = 5 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, and 48 h after injection. Plasma and HDL (phosphotungstate/MgCl2 precipitation) were immediately isolated and stored at 4°C prior radioactivity measurement in a liquid scintillation counter (10 µL plasma or HDL counted). Feces were collected over 48 h and were stored at 4°C before cholesterol and bile acids extraction as described above.

Plasma and HDL decay curves were normalized to radioactivity at the initial 5 min time point after 3H-cholesteryl oleate-labeled HDL injection. Plasma and HDL FCR was then calculated from the area under the plasma disappearance curves fitted to a bicompartmental model using the SAAM II software.

Ex vivo cholesterol efflux assay.

Ex vivo cholesterol efflux capacity of hamster serum was measured as described by Fournier et al. (23) and Mweva et al. (24) (VascularStrategies LLC, Wynnewood, PA). ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux was determined in J774 mouse macrophages. Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI)-mediated cholesterol efflux was assessed in Fu5AH rat hepatoma cells. ABCG1-mediated efflux was assessed in baby hamster kidney cells overexpressing human ABCG1.

Bulk cholesterol/lipoprotein composition studies.

Bulk cholesterol and lipoprotein composition studies were performed at Merck Research Laboratories (Rahway, NJ). For determination of the effects of ANA treatment on lipoporotein composition and bulk cholesterol excretion, hamsters were administered dyslipidemic diet and treated with ANA as described above (n = 8 per group). Following ANA treatment, blood was collected and plasma isolated by low-speed centrifugation and stored at −80°C until analysis was performed. Feces were collected over a 24 h period prior to and following 2 weeks of treatment with either vehicle or ANA. A separate cohort of hamsters was used to determine possible effects of ANA on cholesterol absorption. In this study, the diet conditions and treatment were identical as described above with the inclusion of a group of animals treated with ezetimibe (n = 8) (1.5 mg/kg admixed into the diet) as a positive control for cholesterol absorption inhibition. In this cohort, hamsters were administered D6-cholesterol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) orally at a dose of 12 mg/kg. Feces were collected over a 24 h period following administration of D6-cholesterol at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h intervals. Fecal samples were frozen at −20°C until analyzed by LC/MS.

Serum lipoprotein analysis by gel electrophoresis.

Gel electrophoresis was employed in this study to separate lipoproteins for quantitating the cholesterol component in VLDL, LDL, and HDL fractions. This method was selected as it permits not only in-gel quantitation of cholesterol but also isolation of lipoprotein subfraction bands and post hoc analysis of lipid composition with high-resolution mass spectrometry.

Gel electrophoresis was performed using a commercially available kit (Lipoprint®, Quantimetrix, Redondo Beach, CA). Twenty five microliters of serum was loaded onto the gel and gels were run according to manufacturer's instructions. Gels were stained with Sudan black B and scanned for quantitation of cholesterol and CE in each lipoprotein band. Quantitation was performed by comparing the percentage of stain to the total stain of bands within the gel, and the total serum cholesterol concentration was measured by the Wako E cholesterol kit (Richmond, VA).

Lipoprotein lipid composition analysis by LC/MS.

VLDL, LDL, and HDL lipoprotein bands were cut from Lipoprint gels. Gel fragments were homogenized in PBS at 5,000 rpm for 15 s at room temperature, and homogenates were centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 10 min at 10°C. The resulting supernatant was extracted for lipids using the Bligh and Dyer method (25).

Lipid analysis by LC/MS was conducted using nonendogenous internal standards [(1,2-diheptadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC 17:0/17:0), 1-heptadecanoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (LysoPC 17:0), triheptadecanoin (TG 17:0/17:0/17:0), CE (CE 17:0) (Avanti Lipids, Alabaster, AL) and D6-cholesterol (Sigma)] standards were added to samples at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. In addition to this, external lipid calibrants [CEs (CE 16:0, CE 18:0, CE 18:1, CE 18:2, CE 18:3, CE 20:4, and CE 22:6) and free cholesterol (FC) (Avanti Lipids, Alabaster, AL)] in buffer ranging from 0.01 to 2 μg/ml were used for lipid quantitation.

The subsequent lipid extracts were analyzed on a hybrid orthogonal quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Synapt G2 HDMS, Waters, Manchester, UK). Positive ESI mode was utilized for the CE and TG analysis and atmospheric pressure photoionization mode was utilized for the measurement of FC in the lipoprotein fractions as described by Castro-Perez et al. (26). The mass spectrometer was coupled to an inlet system comprised of an Acquity UPLC (Waters, Milford, MA). Lipid extracts were injected (10 µL) onto a 1.8 µm particle 100 × 2.1 mm id Waters Acquity HSS T3 column (Waters); the column was maintained at 55°C. The flow rate used for these experiments was 0.4 ml/min. A binary gradient system consisting of acetonitrile (Burdick and Jackson) and water with 10 mM ammonium formate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (40:60, v/v) was used as eluent A. Eluent B, consisted of acetonitrile and isopropanol (Burdick and Jackson) both containing 10 mM ammonium formate (10:90, v/v). The sample analysis was performed by using a linear gradient (curve 6) over a 15 min total run time; during the initial portion of the gradient, it was held at 60% A and 40% B. For the next 10 min, the gradient was ramped in a linear fashion to 100% B and held at this composition for 2 min. The system was then switched back to 60% B and 40% A and equilibrated for an additional 3 min.

Fecal cholesterol and bile acid composition analysis by LC/MS.

Fecal samples were weighed and homogenized in 10 ml of 80% methanol 20% water in 50 ml Falcon tubes. The volume was increased to 20 ml if the weight of feces per animal exceeded 2 g. The samples were then incubated at room temperature for ∼30 min. Homogenates were then homogenized at 30,000 rpm for 3 min at room temperature. For neutral lipid extraction, 200 μl of the homogenate was transferred to an eppendorff tube, and 320 μl of dichloromethane containing 10 μg/ml D6-cholesterol (internal standard) and 5 μg/ml D6-cholesterol ester 18:2 internal standard was added to all the samples. For cholesterol absorption experiments, 13C18 CE 18:1 was used as the internal standard. Samples were vortexed for 60 s and 80 μl of H2O was added to each sample followed by another vortex cycle of 60 s. Samples were centrifuged at 20,000 rpm, 10°C for 10 min. Seventy five microliters of the lower organic layer was transferred to a 96-deep-well plate and diluted with 300 μl of injection solvent (65% acetonitrile:30% isopropanol:5% water). The plate was then centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min to pellet any residual solids. One hundred microliters of the supernatant was transferred to a new 96-well plate which was then sealed before analysis by LC/MS. External calibration curves were used for FC and CE measurements are described in the Methods section above.

For bile acid extraction from the fecal samples, 10 μl of the fecal homogenate was transferred to a 1.5 ml eppendorff tube, and the homogenate was diluted with 490 μl of 80% methanol containing 500 nM D4-cholic acid as the internal standard. The resulting mixture was then vortexed for 60 and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 10°C. One hundred microliters of the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and centrifuged again for 10 min to pellet any residual solids. The supernatant was transferred to a new 96-well plate for analysis. Resulting analyte concentrations for the samples were computed against each calibration line for the corresponding bile acid.

Data processing and statistical analysis.

Unless stated otherwise, data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed t-test was employed with a P-value < 0.05 being considered significant. For lipoprotein analysis using gel electrophoresis (Lipoprint), data processing was conducted using the manufacturer's software. Lipid composition and quantitation analysis from LC/MS experiments was carried out using MassLynx (Waters).

Lipid nomenclature.

The lipid nomenclature utilized throughout the paper is the same as described by Fahy et al. (27). For instance, CE 18:1 denotes CE containing 18 hydrocarbons and 1 double bond as the fatty acyl substituent. The same applies to TG cited in the article. For example, TG 54:3, translates to a TG containing 54 hydrocarbons attached to the glycerol back-bone and a total of three double bonds, which forms part of the three fatty acyl substituents.

RESULTS

RCT/FCR studies

Two weeks of ANA treatment was associated with reduced CETP activity and increased HDL-C with no effect on LDL-C.

There were no significant differences in serum TG, TC, HDL-C, or nonHDL-C between control and ANA groups prior to treatment (data not shown).

Two weeks of treatment with 60 mg/kg ANA in the diet resulted in serum ANA concentrations of 4.6 ± 0.6 μM at the time of blood collection for lipid and CETP activity analysis. Treatment with ANA was associated with 94% lower CETP activity compared with control animals (CETP activity control 43.3 ± 1.4, ANA 2.4 ± 0.4 pmol/μl/h; P < 0.001 vs. control).

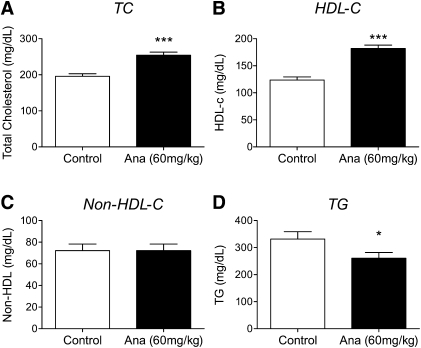

As shown in Fig. 1, ANA treatment resulted in a 47% increase in HDL-C levels compared with control animals (P < 0.001). The lack of any effect on nonHDL-C with ANA treatment suggests the increase in TC observed is primarily due to the change in HDL-C. A reduction in total plasma triglyceride was also observed with ANA treatment.

Fig.1.

CETP inhibition with ANA (60 mg/kg, 2 weeks) in dyslipidemic hamsters increases plasma HDL-cholesterol but not nonHDL-cholesterol. Lipids were measured as described in Methods. ANA treatment (solid bars) was associated with (A) increased total cholesterol, (B) increased HDL-cholesterol, (C) no change in nonHDL-cholesterol, and (D) reduced triglyceride. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05 versus control. Open bars, control; solid bars, ANA treated; n = 24 per group.

ANA promotes macrophage-to-feces RCT.

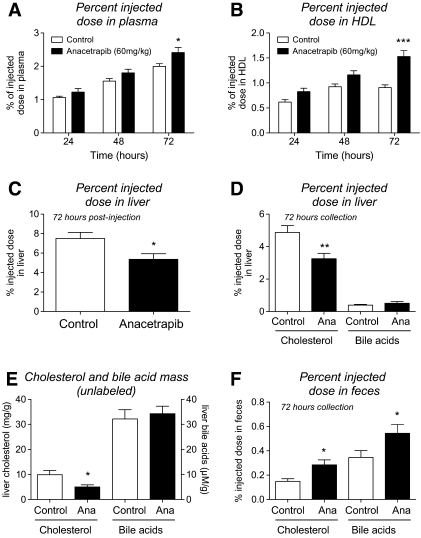

To determine whether ANA treatment affected RCT, radiolabeled cholesterol-loaded macrophages were injected in hamsters following treatment with either control or ANA-containing diets. As shown in Fig. 2A, the appearance of tracer in plasma was 20% higher in animals treated with ANA compared with controls at 72 h. When HDL was isolated from plasma, the appearance of tracer in HDL from ANA-treated animals was 69% higher than that of control animals at 72 h (Fig. 2B). When liver radioactivity was measured, animals treated with ANA displayed 29% lower amount of tracer in the liver compared with controls (Fig. 2C). The majority of this decrease was attributable to a 33% reduction in 3H-cholesterol compared with controls (Fig. 2D). Liver 3H-bile acids were not different between groups. Liver cholesterol mass (unlabeled) was also decreased in ANA-treated hamsters compared with vehicle and bile acid mass was unchanged (Fig. 2E). As shown in Fig. 2F, ANA treatment was associated with a significant increase in both fecal 3H-cholesterol and 3H-bile acids by 90 and 57%, respectively.

Fig.2.

Effects of ANA treatment (60 mg/kg, 2 weeks) of dyslipidemic hamsters on macrophage-to-feces RCT. A: 3H-tracer recovery in plasma; B: 3H-tracer recovery in HDL fraction of plasma; C: 3H-tracer recovery in liver tissue; D: 3H-tracer recovery in liver cholesterol and bile acid fraction; E: liver cholesterol and bile acid mass (unlabeled); F: 3H-tracer recovery in fecal cholesterol and bile acid fraction. ***P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 versus control. Open bars, control; solid bars, ANA treated; n = 12 per group.

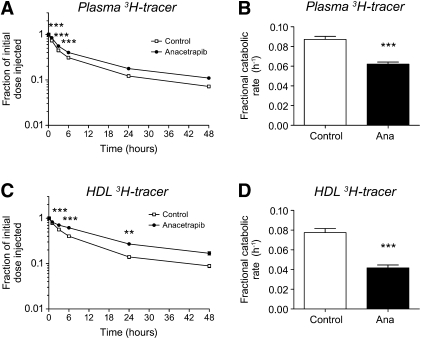

To further determine the effects of ANA on cholesterol flux, hamsters were injected with 3H-cholesteryl oleate-labeled HDL, and the rate of 3H-tracer disappearance from plasma and HDL was determined. As shown in Fig. 3, ANA treatment was associated with a slower rate of 3H tracer decay in plasma over the 48 hr monitoring period. This is reflected as a 29% reduction in FCR (Fig. 3B). The same trend was observed when the degree of tracer decay was monitored in the HDL fraction (Fig. 3C, D), where ANA treatment was associated with a 48% reduction in FCR of 3H-tracer. The reductions in 3H-tracer from both plasma and HDL therefore indicate that CETP inhibition with ANA increases HDL-C levels through a reduction of FCRs. From this experiment, liver and feces radioactivity were also measured 48 h after treatment. As was observed with 3H-labeled macrophages, ANA treatment was associated with decreased liver radioactivity (vehicle 38 ± 4%, ANA 30 ± 2% of injected dose, P < 0.05) and a nonsignificant trend toward increased fecal 3H-cholesterol and bile acids was observed with ANA treatment (fecal 3H-cholesterol: vehicle 0.08 ± 0.01%, ANA 0.09 ± 0.02% P = 0.4; 3H-bile acids: vehicle 0.07 ± 0.01%, ANA 0.1 ± 0.01% P = 0.09).

Fig.3.

Effects of ANA treatment (60 mg/kg, 2 weeks) of dyslipidemic hamsters on HDL-cholesteryl ester kinetics. A: Time course of 3H-tracer recovery in plasma; B: fractional catabolic rate of 3H-tracer in plasma; C: time course of 3H-tracer recovery in HDL fraction of plasma; D: fractional catabolic rate of 3H-tracer in HDL fraction. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 versus control. Open bars, control; solid bars, ANA treated; n = 12 per group.

Bulk cholesterol and lipid composition analysis

For analysis of changes in bulk cholesterol and lipoprotein composition with ANA treatment, a separate cohort of hamsters were subjected to the same diet and drug treatment conditions as the RCT/FCR studies described above. Two weeks of treatment with 60 mg/kg ANA in the diet resulted in serum ANA concentrations of 7.8 ± 1.9 μM. Analysis of HDL-C with gel electrophoresis (Lipoprint) showed a similar degree of increase in HDL-C with ANA treatment as was observed in the RCT study (53% increase compared with vehicle-treated). Also similar to the RCT study, no change in LDL/intermediate density lipoprotein/VLDL cholesterol was observed with ANA treatment (data not shown).

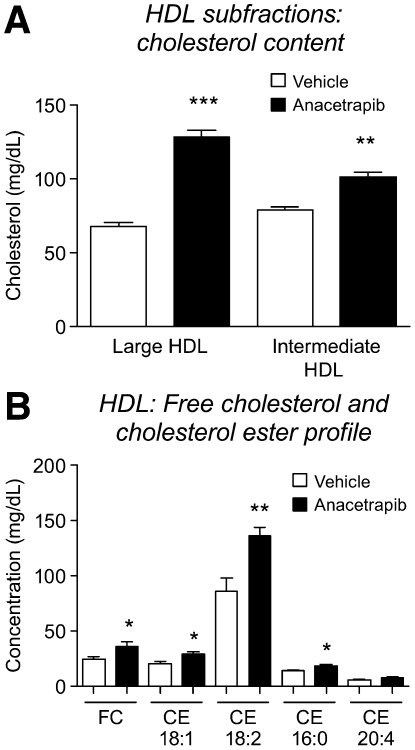

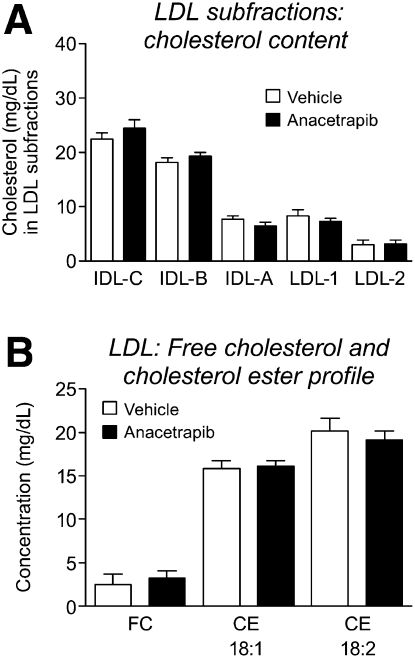

From analysis of HDL from gel electrophoresis, a greater degree of increase in cholesterol content in ANA-treated HDL was observed in large HDL particles (increase of 89% vs. vehicle) compared with intermediate HDL particles(increase of 29% vs. vehicle) (Fig. 4A). LC/MS analysis of FC and CE species in total HDL revealed significant increases in FC (increase of 33% vs. vehicle) and major CE species in ANA-treated hamster HDL, with the greatest increase observed with CE 18:2 (57% vs. vehicle) (Fig. 4B). No change in cholesterol or CE content was observed across the LDL subfractions (Fig. 5). This is similar to the lack of effect on LDL observed in the RCT study.

Fig.4.

Changes in HDL cholesterol composition with anacetrapib treatment. A: Increase in HDL total cholesterol is more prominent in large HDL fraction; B: majority of increase driven by free cholesterol and cholesteryl linoleate (18:2). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle.

Fig.5.

Lack of change in LDL cholesterol distribution with anacetrapib treatment. A: Distribution of cholesterol in LDL subfractions, and (B) major cholesterol species present in LDL.

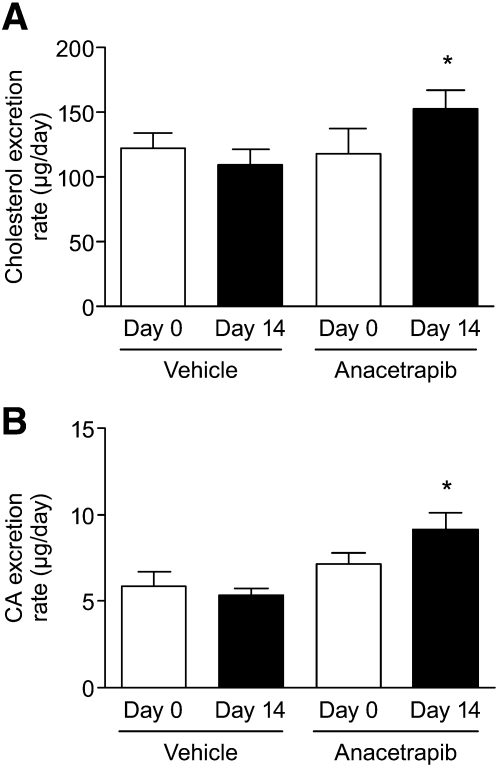

Fecal cholesterol excretion following CETP inhibition.

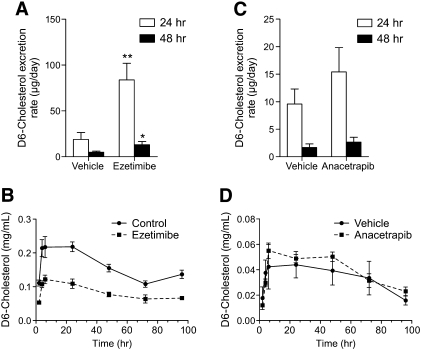

Treatment with ANA resulted in 30% increase in fecal cholesterol content compared with vehicle (Fig. 6). Cholic acid content (Fig. 6) was also increased by 29% in ANA-treated animals compared with vehicle. To determine whether the increase in fecal cholesterol content was due to effects on intestinal absorption, the appearance of orally administered D6-labeled cholesterol in the feces was used as an index of absorption. D6-cholesterol appeared in the feces over the course of 48 h for all animal groups. Time points beyond 48 h showed levels of D6-cholesterol near the limit of detection (data not shown). The positive control ezetimibe, which inhibits cholesterol absorption as an inhibitor of intestinal NPC1L1, showed a marked increase in fecal D6-cholesterol content (344%) over vehicle samples during the first 24 h after tracer administration (Fig. 7A). Fecal D6-cholesterol concentration was not different between vehicle and ANA treated hamster fecal samples (Fig. 7C). Plasma circulating levels of D6-cholesterol were determined by LC/MS analysis. For ezetimibe-treated animals, the area under the curve for plasma D6 cholesterol was significantly reduced (Fig. 7B) (reduction of 99.6%) For animals treated with ANA (Fig. 7D), plasma D6 cholesterol was slightly but not significantly increased (area under the curve increase of ∼15%).

Fig.6.

Anacetrapib treatment increases (A) fecal cholesterol and (B) fecal cholic acid excretion. * P < 0.05 versus day 0.

Fig.7.

Anacetrapib treatment does not affect cholesterol absorption. A: Fecal D6-cholesterol excretion over the time-course of 48 hr for vehicle and ezetimibe treated hamsters. B: Plasma levels of D6-cholesterol for vehicle and ezetimibe treated hamsters. C: Fecal D6-cholesterol excretion over the time-course of 48 hr for vehicle and anacetrapib treated hamsters. D: Plasma levels of D6-cholesterol for vehicle and anacetrapib treated hamsters. **P < 0.01 ezetimibe 24 h versus vehicle 24 h; *P < 0.05 ezetimibe 48 h versus vehicle 48 h.

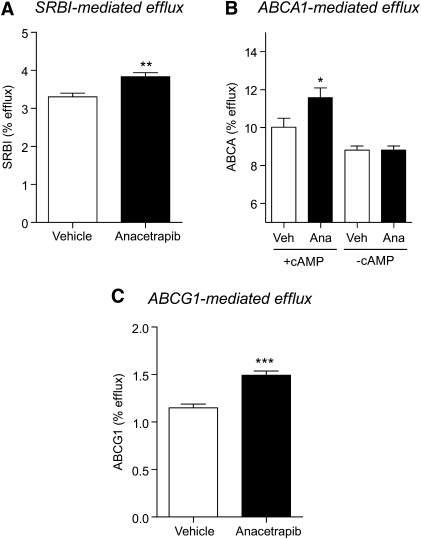

HDL from hamsters treated with ANA exhibited increased cholesterol efflux capacity.

A statistically significant increase in SR-BI-mediated efflux (P = 0.003) in the ANA group was observed (3.83% ± 0.30%) versus the vehicle group (3.30% ± 0.27%) (Fig. 8A). In the ABCA1-dependent efflux assay, treatment of cells with ANA treated plasma was associated with an increase in the average cholesterol efflux compared with vehicle in the ABCA1-upregulated group (11.58 ± 0.51% vs. 10.01 ± 0.48%, P < 0.05; Fig. 8B) but not in the group in which ABCA1 was not upregulated. ANA-treated plasma was also associated with an increase in ABCG1-mediated efflux compared with vehicle controls (1.49 ± 0.05% vs. 1.15 ± 0.04%, P < 0.001).

Fig.8.

Cholesterol efflux was increased in HDL from anacetrapib-treated hamsters. A: SR-BI mediated cholesterol efflux. B: Cholesterol efflux ± ABCA1 upregulation with cAMP. C: ABCG1 mediated cholesterol efflux. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 versus vehicle.

DISCUSSION

Inhibitors of CETP are being evaluated clinically for managing the treatment of cardiovascular disease, relying on the hypothesis that prevention of transfer of cholesterol ester from HDL to LDL will reduce levels of atherogenic CE associated with LDL and promote removal of cholesterol from blood vessel macrophages and excretion into the feces. The process of RCT involves efflux of cholesterol from peripheral tissues onto HDL particles, which transport the cholesterol to the liver for biliary excretion into the feces as cholesterol and bile acids (28). The method most widely used to examine effects of dietary challenge and pharmacotherapy on RCT is the labeled macrophage method described by Rader and Rothblat (16–21). This method utilizes J774 macrophages labeled in vitro with 3H-cholesterol and oxidized LDL and monitors the movement of 3H-tracer into cholesterol and bile acid pools in plasma, liver, and feces following injection into animals. This method has been used in hamsters to examine the effects of several pharmacotherapies on macrophage-to-feces RCT, including liver X receptor activation (22) and CETP inhibition with torcetrapib (29). To comprehensively assess the effects of a pharmacological intervention on cholesterol handling and excretion, it is important not only to study macrophage-to-feces RCT but also to take into account the bulk movement of cholesterol mass within lipoproteins and in the fecal compartment.

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the effects of CETP inhibition with ANA on RCT, cholesterol mass, and lipoprotein composition using multiple approaches in a hamster model of dyslipidemia. The dyslipidemic hamster provides an advantage in the study of CETP, as it expresses CETP endogenously (unlike mice and rats). The results from the current study are the first to describe promotion of RCT and bulk cholesterol excretion by ANA in a hamster model of dyslipidemia. This is evidenced by data generated from two independent and distinct study designs: one that shows an increase in tracer appearance in plasma, HDL, and feces following injection of labeled macrophages, and another that shows an increase in CE content in large HDL particles and an increase in the fecal content of both neutral sterols and bile acids. In combination with the in vitro cholesterol efflux data, showing an improvement in the ability of ANA-treated hamster HDL to collect cholesterol from macrophages, the results of this study strongly support the hypothesis that ANA promotes a shift of the cholesterol pool out of the body via HDL trafficking.

The rationale for using hamsters fed a high-fat (“Western-type”) diet was to more closely mimic the state of dyslipidemia seen in the clinic. Although the LDL-C levels were still relatively low in this model, the goal was to increase the amount of cholesterol that was absorbed from the diet providing substrate for the CETP system, similar to what occurs in the patient population currently consuming a Western diet. Indeed, the dyslipidemic hamster has been used to examine multiple mechanism/pharmacological interventions and their effects on RCT and cholesterol excretion (reviewed in Ref. 16). A single study by Niesor et al. (30) reported a lack of effect of ANA in a different model of RCT in normolipidemic hamsters. Although the goal of the current study was not to examine the effects of ANA in normal animals, but rather in dyslipidemic animals, it is possible that the methodological differences in how RCT was tested in each study (including the method of labeling macrophages, duration of feces monitoring) in addition to the dietary conditions used could have contributed to the different results reported. In the current study, we observed an increase in the fecal excretion of 3H-neutral sterols and 3H-bile acids (both derived from labeled macrophages) and of unlabeled cholesterol and bile acid, in two separate studies. The congruence of in vivo data from two experimental approaches in a disease model coupled with in vitro efflux data strengthens the finding that ANA promotes cholesterol movement from the macrophage to the feces.

Interestingly, in the RCT study, in both 3H-labeled macrophage and 3H-labeled HDL experiments, a lower hepatic 3H-tracer recovery was observed. The liver 3H recovery in the current study was examined at a single time point, which may not represent the intermediate role of the liver in the overall biliary flux of cholesterol from HDL to the feces. Using a hamster model of RCT, Tchoua et al. (29) demonstrated that CETP inhibition with torcetrapib promoted macrophage-to-feces RCT without increasing 3H-cholesterol in the liver. Although it is beyond the scope of the current study, it would be useful to determine the kinetics of the appearance and disappearance of tracer in the liver over time to determine the timing of 3H-cholesterol appearance into HDL, liver, and, ultimately, feces.

In the current study, gel electrophoresis was used to quantitate lipoprotein composition, due to the high degree of separation of different LDL, IDL, and HDL subfractions, and the ability to isolate these fractions for LC/MS analysis. Between the RCT and bulk cholesterol studies, we saw good agreement in the degree of HDL-C increase with ANA treatment between the phosphotungstate-MgCl2 precipitation method (RCT study) and gel electrophoresis method (bulk cholesterol study). LC/MS analysis of lipoproteins showed that all sterols (FC and CEs) were upregulated in the HDL fraction with CE 18:2 being the most abundant CE component of the HDL fraction. It has been shown in rodents that LCAT preferentially hydrolyses phosphatidylcholines containing linoleate (18:2) as the fatty acyl motif in the sn-2 position (31, 32). In the current study, levels of FC were upregulated in the HDL fraction from ANA-treated animals, which could provide increased cholesterol scaffold for LCAT esterification.

The majority of the increase in HDL-C occurred in large HDL particles. This result is similar to findings by Matsuura et al. (33), who described that large spherical HDL particles are good acceptors of cholesterol from macrophages (cholesterol efflux). In that study, samples were analyzed from human subjects genetically deficient in CETP and the results described the presence of large HDL-2 particles. In these genetically deficient subjects, cholesterol efflux from macrophages was enhanced by 2- to 3-fold with respect to control HDL-2 in liver X receptor activated macrophages (34). Furthermore, Yvan-Charvet et al. (35) recently reported that plasma from humans treated with ANA showed enhanced cholesterol efflux capacity in vitro. Both of these reports are consistent with the in vitro cholesterol efflux data from the current study where an increase in efflux capacity of HDL from CETP-inhibited animals was observed.

In both experiments from the current study, the increase in HDL-C relative to CETP inhibition is similar to what has been reported in normolipidemic and dyslipidemic hamsters using both small molecules and antibody approaches (29, 30, 36). Although this increase in HDL-C is consistent with what is observed by others in similar preclinical models, no reduction in LDL-C was observed, which is in contrast to what is observed in humans. Although high-fat/high-cholesterol diet does increase LDL-C in the hamster above what is observed on normal diet (17, 22), the Syrian golden hamster still appears to carry less cholesterol on LDL. Blockade of cholesterol absorption with ezetimibe will reduce LDL-C in a dyslipidemic hamster model (37) and has been shown to promote RCT in mice due to inhibition of reabsorption of 3H-cholesterol derived from injected macrophages (38). The dyslipidemic hamster model has been used with limited success to study the LDL-lowering effects of statins (39, 40). Therefore, whereas prevention of intestinal absorption of cholesterol from the diet would directly affect LDL-C levels in a dietary model, removal of LDL via increased clearance by statins or by CETP inhibition appears more difficult to reproduce in the dyslipidemic hamster, due possibly to a greater upregulation of PCSK9 compared with LDL receptor as reported by Dong et al. (41). Regardless, the effects of ANA on cholesterol excretion and RCT are clear from the current study, and it is tempting to speculate whether an even greater increase in cholesterol excretion might be observed in a model where ANA lowers LDL-C (i.e., in a nonhuman primate) where LDL-C and HDL-C levels are much more similar to the human.

In summary, the current study used multiple in vivo and in vitro approaches to assess the effects of anacetrapib on cholesterol metabolism in the dyslipidemic Syrian golden hamster. Taken together, the data from these independent approaches indicate that in this model, anacetrapib promotes both macrophage-to-feces RCT and the movement of the bulk cholesterol pool from the body and into the feces, with strong evidence that anacetrapib improves the ability of HDL to remove cholesterol from the system. Therefore, these results support the development of anacetrapib as a treatment for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ANA

- anacetrapib

- CE

- cholesteryl ester

- CETP

- cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- FC

- free cholesterol

- FCR

- fractional catabolic rate

- HDL-C

- high density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

- low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- RCT

- reverse cholesterol transport

- TC

- total cholesterol

- TG

- triglyceride

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon T., Castelli W. P., Hjortland M. C., Kannel W. B., Dawber T. R. 1977. High-density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart-disease - Framingham Study. Am. J. Med. 62: 707–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller N. E., Thelle D. S., Forde O. H., Mjos O. D. 1977. Tromso Heart-Study - high-density lipoprotein and coronary heart-disease - prospective case-control study. Lancet. 1: 965–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keys A. 1980. Alpha-lipoprotein (Hdl) cholesterol in the serum and the risk of coronary heart-disease and death. Lancet. 2: 603–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namboodiri K. K., Bucher K. D., Kaplan E. B., Laskarzewski P. M., Glueck C. J., Rifkind B. M. 1985. A major gene for low-levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol - the Collaborative Lipid Research Clinics Family Study. Clin. Res. 33: A890. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs D. R., Mebane I. L., Bangdiwala S. I., Criqui M. H., Tyroler H. A. 1990. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as a predictor of cardiovascular-disease mortality in men and women - the follow-up-study of the Lipid Research Clinics Prevalence Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 131: 32–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitamura A., Iso H., Naito Y., Iida M., Konishi M., Folsom A. R., Sato S., Kiyama M., Nakamura M., Sankai T., et al. 1994. High-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and premature coronary heart-disease in urban Japanese men. Circulation. 89: 2533–2539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson M. H., McKenney J. M., Shear C. L., Revkin J. H. 2006. Efficacy and safety of torcetrapib, a novel cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor, in individuals with below-average high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48: 1774–1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKenney J. M., Davidson M. H., Shear C. L., Revkin J. H. 2006. Efficacy and safety of torcetrapib, a novel cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor, in individuals with below-average high-density lipoproteín cholesterol levels on a background of atorvastatin. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48: 1782–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barter P. J., Caulfield M., Eriksson M., Grundy S. M., Kastelein J. J. P., Komajda M., Lopez-Sendon J., Mosca L., Tardif J., Waters D. D., et al. 2007. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N. Engl. J. Med. 357: 2109–2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forrest M. J., Bloomfield D., Briscoe R. J., Brown R. N., Cumiskey A. M., Ehrhart J., Hershey J. C., Keller W. J., Ma X., McPherson H. E., et al. 2008. Torcetrapib-induced blood pressure elevation is independent of CETP inhibition and is accompanied by increased circulating levels of aldosterone. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154: 1465–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DePasquale M., Cadelina G., Knight D., Loging W., Winter S., Blasi E., Perry D., Keiser J. 2009. Mechanistic studies of blood pressure in rats treated with a series of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors. Drug Dev. Res. 70: 35–48 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu X., Dietz J. D., Xia C. S., Knight D. R., Loging W. T., Smith A. H., Yuan H. D., Perry D. A., Keiser J. 2009. Torcetrapib induces aldosterone and cortisol production by an intracellular calcium-mediated mechanism independently of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibition. Endocrinology. 150: 2211–2219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishna R., Bergman A. J., Jin B., Fallon M., Cote J., Van Hoydonck P., Laethem T., Gendrano I. N., 3rd, Van Dyck K., Hilliard D., et al. 2008. Multiple-dose pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of anacetrapib, a potent cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitor, in healthy subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 84: 679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloomfield D., Carlson G. L., Sapre A., Tribble D., McKenney J. M., Littlejohn W. T., 3rd, Sisk C. M., Mitchel Y., Pasternak R. C. 2009. Efficacy and safety of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor anacetrapib as monotherapy and coadministered with atorvastatin in dyslipidemic patients. Am. Heart J. 157: 352–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannon C. P., Shah A., Dansky H. M., Davidson M., Brinton E. A., Gotto A. M., Stepanavage M., Liu S. X., Gibbons P., Ashraf T. B., et al. 2010. Safety of anacetrapib in patients with or at high risk for coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 363: 2406–2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rader D. J., Alexander E. T., Weibel G. L., Billheimer J., Rothblat G. H. 2009. The role of reverse cholesterol transport in animals and humans and relationship to atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 50: S189–S194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briand F. 2010. The use of dyslipidemic hamsters to evaluate drug-induced alterations in reverse cholesterol transport. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 11: 289–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y., Zanotti I., Reilly M. P., Glick J. M., Rothblat G. H., Rader D. J. 2003. Overexpression of apolipoprotein A-I promotes reverse transport of cholesterol from macrophages to feces in vivo. Circulation. 108: 661–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naik S. U., Wang X., Da Silva J. S., Jaye M., Macphee C. H., Reilly M. P., Billheimer J. T., Rothblat G. H., Rader D. J. 2006. Pharmacological activation of liver X receptors promotes reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. Circulation. 113: 90–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Da Silva J. R., Reilly M., Billheimer J. T., Rothblat G. H., Rader D. J. 2005. Hepatic expression of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) is a positive regulator of macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 115: 2870–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore R. E., Navab M., Millar J. S., Zimetti F., Hama S., Rothblat G. H., Rader D. J. 2005. Increased atherosclerosis in mice lacking apolipoprotein A-I attributable to both impaired reverse cholesterol transport and increased inflammation. Circ. Res. 97: 763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briand F., Treguier M., Andre A., Grillot D., Issandou M., Ouguerram K., Sulpice T. 2010. Liver X receptor activation promotes macrophage-to-feces reverse cholesterol transport in a dyslipidemic hamster model. J. Lipid Res. 51: 763–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fournier N., Francone O., Rothblat G., Goudouneche D., Cambillau M., Kellner-Weibel G., Robinet P., Royer L., Moatti N., Simon A., et al. 2003. Enhanced efflux of cholesterol from ABCA1-expressing macrophages to serum from type IV hypertriglyceridemic subjects. Atherosclerosis. 171: 287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mweva S., Paul J. L., Cambillau M., Goudouneche D., Beaune P., Simon A., Fournier N. 2006. Comparison of different cellular models measuring in vitro the whole human serum cholesterol efflux capacity. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 36: 552–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37: 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro-Perez J., Previs S. F., McLaren D. G., Shah V., Herath K., Bhat G., Johns D. G., Wang S. P., Mitnaul L., Jensen K., et al. 2011. In vivo D2O labeling to quantify static and dynamic changes in cholesterol and cholesterol esters by high resolution LC/MS. J. Lipid Res. 52: 159–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fahy E., Subramaniam S., Murphy R.C., Nishijima M., Raetz C.R., Shimizu T., Spener F., van Meer G., Wakelam M.J., Dennis E.A. 2009. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res 50 Suppl:S9–S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuchel M., Rader D. J. 2006. Macrophage reverse cholesterol transport: key to the regression of atherosclerosis? Circulation. 113: 2548–2555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tchoua U., D'Souza W., Mukhamedova N., Blum D., Niesor E., Mizrahi J., Maugeais C., Sviridov D. 2008. The effect of cholesteryl ester transfer protein overexpression and inhibition on reverse cholesterol transport. Cardiovasc. Res. 77: 732–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niesor E. J., Magg C., Ogawa N., Okamoto H., von der Mark E., Matile H., Schmid G., Clerc R. G., Chaput E., Blum-Kaelin D., et al. 2010. Modulating cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity maintains efficient pre-β-HDL formation and increases reverse cholesterol transport. J. Lipid Res. 51: 3443–3454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grove D., Pownall H. J. 1991. Comparative specificity of plasma lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase from ten animal species. Lipids. 26: 416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu M., Bagdade J. D., Subbaiah P. V. 1995. Specificity of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and atherogenic risk: comparative studies on the plasma composition and in vitro synthesis of cholesteryl esters in 14 vertebrate species. Lipid Res. 36: 1813–1824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuura F., Wang N., Chen W., Jiang X. C., Tall A. R. 2006. HDL from CETP-deficient subjects shows enhanced ability to promote cholesterol efflux from macrophages in an apoE- and ABCG1-dependent pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 116: 1435–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miwa K., Inazu A., Kawashiri M., Nohara A., Higashikata T., Kobayashi J., Koizumi J., Nakajima K., Nakano T., Niimi M., et al. 2009. Cholesterol efflux from J774 macrophages and Fu5AH hepatoma cells to serum is preserved in CETP-deficient patients. Clin. Chim. Acta. 402: 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yvan-Charvet L., Kling J., Pagler T., Li H., Hubbard B., Fisher T., Sparrow C. P., Taggart A. K., Tall A. R. 2010. Cholesterol efflux potential and antiinflammatory properties of high-density lipoprotein after treatment with niacin or anacetrapib. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30: 1430–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans G. F., Bensch W. R., Apelgren L. D., Bailey D., Kauffman R. F., Bumol T. F., Zuckerman S. H. 1994. Inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer protein in normocholesterolemic and hypercholesterolemic hamsters: effects on HDL subspecies, quantity, and apolipoprotein distribution. J. Lipid Res. 35: 1634–1645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Heek M., Austin T. M., Farley C., Cook J. A., Tetzloff G. G., Davis H. R. 2001. Ezetimibe, a potent cholesterol absorption inhibitor, normalizes combined dyslipidemia in obese hyperinsulinemic hamsters. Diabetes. 50: 1330–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briand F., Naik S. U., Fuki I., Millar J. S., Macphee C., Walker M., Billheimer J., Rothblat G., Rader D. J. 2009. Both the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) delta agonist GW0742, and ezetimibe promote reverse cholesterol transport in mice by reducing intestinal re-absorption of HDL-derived cholesterol. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2: 127–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Himber J., Missano B., Rudling M., Hennes U., Kempen H. J. 1995. Effects of stigmastanyl-phosphocholine (Ro 16–6532) and lovastatin on lipid and lipoprotein levels and lipoprotein metabolism in the hamster on different diets. J. Lipid Res. 36: 1567–1585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ugawa T., Kakuta H., Moritani H., Shikama H. 2002. Experimental model of escape phenomenon in hamsters and the effectiveness of YM-53601 in the model. Br. J. Pharmacol. 135: 1572–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong B., Wu M., Li H., Kraemer F. B., Adeli K., Seidah N. G., Park S. W., Liu J. 2010. Strong induction of PCSK9 gene expression through HNF1alpha and SREBP2: mechanism for the resistance to LDL-cholesterol lowering effect of statins in dyslipidemic hamsters. J. Lipid Res. 51: 1486–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]