Abstract

Excessive absorption of products of dietary fat digestion leads to type 2 diabetes and other obesity-related disorders. Mice deficient in the group 1B phospholipase A2 (Pla2g1b), a gut digestive enzyme, are protected against diet-induced obesity and type 2 diabetes without displaying dietary lipid malabsorption. This study tested the hypothesis that inhibition of Pla2g1b protects against diet-induced hyperlipidemia. Results showed that the Pla2g1b−/− mice had decreased plasma triglyceride and cholesterol levels compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice subsequent to feeding a high-fat, high-carbohydrate (hypercaloric) diet. These differences were evident before differences in body weight gains were observed. Injection of Poloxamer 407 to inhibit lipolysis revealed decreased VLDL production in Pla2g1b−/− mice. Supplementation with lysophosphatidylcholine, the product of Pla2g1b hydrolysis, restored VLDL production rates in Pla2g1b−/− mice and further elevated VLDL production in Pla2g1b+/+ mice. The Pla2g1b−/− mice also displayed decreased postprandial lipidemia compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice. These results show that, in addition to dietary fatty acids, gut-derived lysophospholipids derived from Pla2g1b hydrolysis of dietary and biliary phospholipids also promote hepatic VLDL production. Thus, the inhibition of lysophospholipid absorption via Pla2g1b inactivation may prove beneficial against diet-induced hyperlipidemia in addition to the protection against obesity and diabetes.

Keywords: VLDL synthesis, postprandial lipidemia, gene knockout, lysophospholipid

Obesity and diabetes-related disorders, including atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease, are rapidly reaching pandemic levels in industrialized countries, due at least in part to increasing consumption of high-fat diets in the general population (1–3). Typically, dietary fat is delivered to the intestinal lumen as lipid emulsion particles consisting of a triglyceride and cholesteryl ester core surrounded by a monolayer of phospholipids, cholesterol, and nonesterified fatty acids (4). The lipid emulsions are hydrolyzed by pancreas-secreted lipolytic enzymes into fatty acids, monoacylglycerol, cholesterol, and lysophospholipids prior to the absorption of these lipid nutrients by the enterocytes (4–6). The lipid nutrients in the enterocytes are repackaged and then secreted into plasma circulation as triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (6). These chylomicrons, which are secreted by the intestine, supply lipid nutrients as an energy source to peripheral tissues, and excess fat is deposited in adipose tissues for storage as energy reserve (7). The intestinal-derived chylomicrons and their remnants also transport dietary lipids to the liver, where they are reutilized for VLDL synthesis and further dissipation of the lipid nutrients to extrahepatic tissues (8). Fatty acids stored in adipose tissues as triglycerides can also be liberated from the storage pool and transported to the liver (9, 10). Within the hepatocytes, the fatty acids are used as an energy source through β-oxidation, stored as triglycerides, or repackaged into VLDL for secretion into plasma (11, 12). Obesity and obesity-related metabolic complications ensue when dietary fat intake exceeds the energy requirement of each tissue. The excess fat stored in adipose tissues increases adiposity and promotes inflammation (13, 14). Excess fat uptake into skeletal muscle causes insulin resistance, and excessive fat deposited in the heart leads to lipotoxicity and cardiomyopathy (15, 16). Lipotoxicity of pancreatic islet cells due to excess fat uptake also reduces insulin secretion, resulting in robust hyperglycemia (16).

Recent genome-wide association studies have identified significant association (P < 0.01) between polymorphisms of the group 1B phospholipase A2 (PLA2G1B) gene PLA2G1B with central adiposity in humans (17–19). Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that Pla2g1b inactivation is protective against diet-induced obesity and hyperglycemia in mice (20, 21), suggesting that Pla2g1b contributes directly to these diet-induced metabolic disorders. The Pla2g1b−/− mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity due to their ability to sustain elevated energy expenditure via increased hepatic fatty acid oxidation when fed a hypercaloric diet (22). The elevated fatty acid catabolic rate in the liver of Pla2g1b−/− mice also reduces dietary fat availability to other metabolically active tissues, thereby increasing their dependence on glucose as a fuel source and resulting in protection against diet-induced glucose intolerance and hyperglycemia (23).

The group 1B phospholipase A2 is a 14 kDa protein expressed abundantly in the pancreas and secreted into the intestinal lumen in response to feeding (24). The major function of PLA2G1B is to digest phospholipids into fatty acids and lysophospholipids prior to intestinal absorption of lipid-soluble nutrients. Although other enzymes in the intestinal lumen can compensate for phospholipid digestion in the absence of Pla2g1b in mice (25), they do not produce lysophospholipids to the same extent during the digestive process (23). Reduced lysophospholipid levels in mice deficient in Pla2g1b (Pla2g1b−/− mice) provided the metabolic benefits of obesity and diabetes resistance in these animals, as both elevated hepatic fatty acid oxidation and improved glucose tolerance observed in Pla2g1b−/− mice can be abrogated with lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) supplementation (22, 23).

Although the effects of hypercaloric diet and Pla2g1b inactivation upon glucose response and homeostasis had been examined, whether Pla2g1b inactivation also influences plasma lipid homeostasis in response to hypercaloric feeding has not been determined. The elevation of hepatic fatty acid oxidation in Pla2g1b−/− mice suggests their more favorable lipid profile in response to hypercaloric feeding. This study was initiated to compare plasma lipid levels, hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) output, and postprandial triglyceride-rich lipoprotein clearance between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice in response to high-fat, high-carbohydrate feeding independent of weight gain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal maintenance and feeding protocol

The Pla2g1b−/− mice were generated by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells and backcrossed >10 times with C57BL/6J mice to obtain Pla2g1b−/− mice in homogenous C57BL/6 background (23, 25). Mice from Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mating colonies were used to obtain age-matched Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice for experiments. All animals were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water ad libitum. Only male mice were used for all experiments. They were fed either basal chow diet or a hypercaloric diet (D12331; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ), which consists of 58.5% fat from coconut oil, 25% sucrose, and 16.5% protein beginning at 5-10 weeks of age for the duration as indicated for each experiment. All animal housing and experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Cincinnati.

Plasma lipid determinations

Blood samples were collected from fasting mice through the tail vein or via cardiac puncture into EDTA-containing tubes. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation. Triglyceride and cholesterol levels were measured from plasma diluted in phosphate-buffered saline and assayed using commercial colorimetric kits (Fisher Scientific). Lipid distribution among various lipoproteins was analyzed by applying 200 µl of plasma samples to fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) gel filtration on two Superose 6 HR columns as described (26). Each fraction (0.5 ml) was collected for triglyceride and cholesterol measurements.

Hepatic VLDL production

Animals were fasted for 12 h beginning at 3-4 h into the dark cycle. Blood samples were collected to measure fasting plasma lipid levels at baseline. The mice were then given an intraperitoneal injection of Poloxamer 407 (P407) at a dosage of 1 g/kg body weight to inhibit lipolysis. For LPC supplementation studies, each mouse received 32 mg/kg of LPC, a dosage previously shown to restore LPC levels in Pla2g1b−/− mice to those observed in Pla2g1b+/+ mice (22, 23), 1 h prior to P407 injection. Hourly blood samples were collected for plasma triglyceride measurements to determine hepatic VLDL production rates (27). Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated by trapezoidal rule and averaged. Plasma apoB levels were measured by an ELISA kit (Uscn Life Science). In selected experiments, 1 µCi of [3H]LPC was included as tracer to assess potential use of LPC as substrate for VLDL synthesis.

Postprandial lipid clearance

Ten-week old mice were placed on hypercaloric diet for three weeks. The animals were then fasted overnight, and blood samples were collected to measure baseline plasma lipid levels. Each mouse received an oral gavage of olive oil (400 µl), and hourly blood samples were collected for plasma triglyceride determinations. AUC was calculated by trapezoidal rule and averaged.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means ± SEM. For comparison of means, an unpaired Student t-test was used assuming equal variance. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant differences between groups. For multiple comparisons, a one-way ANOVA with P < 0.05 was used to determine differences.

RESULTS

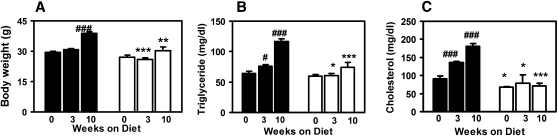

Consistent with results reported previously (20), age-matched male Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice displayed similar body weights when fed basal chow diet. When the animals were challenged with a high fat/sucrose hypercaloric diet, significant body weight gain was observed in the Pla2g1b+/+ mice in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the Pla2g1b−/− mice were resistant to body weight gain, with 12% increase in body weight compared with the 31% increase observed in Pla2g1b+/+ mice after 10 weeks of feeding the hypercaloric diet (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Responses of Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice to hypercaloric diet feeding. The Pla2g1b+/+ mice (filled bars) and Pla2g1b−/− mice (open bars) were placed on hypercaloric diets for the time indicated. Body weights (A), fasting plasma triglyceride (B), and cholesterol (C) levels were taken. Results shown are mean ± SE from six Pla2g1b+/+ and five Pla2g1b−/− mice (for weeks 0 and 3 time points) and seven mice in each group at the week 10 time point. *P ≤0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 versus Pla2g1b+/+ mice; and #P ≤ 0.05, ##P ≤ 0.01, and ###P ≤ 0.001 versus week 0 data of the respective genotype.

Fasting plasma triglyceride levels were similar between chow-fed Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice. However, whereas the Pla2g1b+/+ mice showed progressive elevation of fasting plasma triglyceride levels during a 10-week hypercaloric diet (Fig. 1B), fasting plasma triglyceride levels did not change in the hypercaloric diet-fed Pla2g1b−/− mice and were significantly lower than those observed in Pla2g1b+/+ mice (Fig. 1B). Thus, after feeding the hypercaloric diet for 10 weeks, plasma triglyceride levels were 37% lower in Pla2g1b−/− mice compared with the wild-type Pla2g1b+/+ mice. The Pla2g1b−/− mice also displayed lower plasma cholesterol levels compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice, even under basal chow dietary conditions (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, whereas the wild-type Pla2g1b+/+ mice reached a hypercholesterolemic state after 10 weeks on the hypercaloric diet as expected (Fig. 1C), fasting plasma cholesterol levels in the Pla2g1b−/− mice were not susceptible to dietary changes, with 67 ± 2 mg/dl and 71 ± 8 mg/dl before and after feeding the hypercaloric diet (Fig. 1C). Thus, at the end of the 10-week hypercaloric diet, plasma cholesterol was 61% lower in Pla2g1b−/− mice compared with the Pla2g1b+/+ mice. FPLC analysis of plasma from hypercaloric diet-fed mice showed that difference in VLDL accounted for the different plasma triglyceride levels between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice. Additionally, the Pla2g1b−/− mice also did not display elevated plasma HDL levels (data not shown), which are typically observed in wild-type mice after high-fat feeding (28).

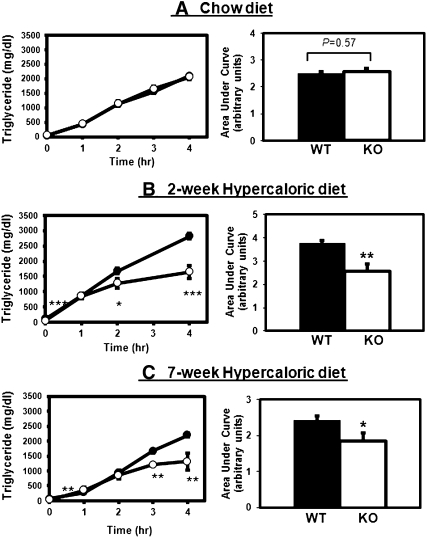

The mechanism underlying the differences in plasma lipid levels between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice was explored by comparing hepatic VLDL production rates in these animals under both basal and hypercaloric dietary conditions. In these experiments, mice were fasted for 12 h to achieve total clearance of chylomicron-associated triglycerides and then injected with P407 to inhibit lipolysis of nascent VLDL secreted by the liver. Plasma samples were collected at hourly intervals, and triglyceride levels were measured (27). When the animals were maintained on a basal chow diet, plasma triglyceride levels were similar between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice before and every hour after P407 injection (Fig. 2A, left). Calculation of hourly changes in plasma triglyceride levels revealed no significant difference in hepatic VLDL production rates between chow-fed Pla2g1b+/+ mice (555 ± 61 mg/dl per h) and Pla2g1b+/+ mice (538 ± 52 mg/dl per h). AUC analysis also revealed no difference in the total amount of triglyceride secreted by chow-fed Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice after 4 h (Fig. 2A, right). In contrast, significant differences in hepatic VLDL production were observed between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice after feeding the hypercaloric diet (Fig. 2B, C). Feeding the hypercaloric diet for two weeks increased hepatic VLDL production rates in Pla2g1b+/+ mice to 651 ± 90 mg/dl per h, whereas the hepatic VLDL production rates actually decreased in Pla2g1b−/− mice to 278 ± 171 mg/dl per h (Fig. 2B, left). At the end of the 4 h experimental period, significantly more VLDL-triglyceride was found in the plasma of Pla2g1b+/+ mice compared with that in Pla2g1b−/− mice (Fig. 2B, right). These differences in diet modulation of hepatic VLDL production rates between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice were observed prior to noticeable changes in their body weights (Fig. 1A). The differences in VLDL production persisted after seven weeks of hypercaloric diet feeding, when differences in body weight gains were also observed. Both the total amount of VLDL secretion over a 4-h period (Fig. 2C, right) and VLDL production rates were significantly higher in Pla2g1b+/+ mice (641 ± 43 mg/dl per h) compared with those in Pla2g1b−/− mice (321 ± 171 mg/dl per h) (Fig. 2C, left).

Fig. 2.

Hepatic VLDL production by Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice. The Pla2g1b+/+ (filled symbols; WT) and Pla2g1b−/− (open symbols; KO) mice were fed basal chow diet (panel A, from five Pla2g1b+/+ and three Pla2g1b−/− mice) or a hypercaloric diet for two (panel B, from nine Pla2g1b+/+ and eight Pla2g1b−/− mice) or seven weeks (panel C from six Pla2g1b+/+ and seven Pla2g1b−/− mice). The mice were fasted for 12 h, and then received an intraperitoneal injection of Poloxamer 407 (1 g/kg body weight). Plasma samples were obtained at hourly intervals for triglyceride measurements. The left panels show time-dependent increases in plasma triglyceride levels, and the right panels show AUC analyses of the respective data. Results represent mean ± SE, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 versus Pla2g1b+/+ mice.

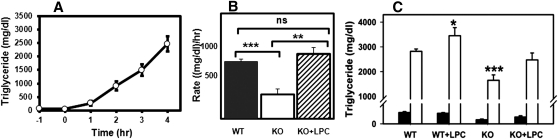

Note that VLDL production reached a saturation level after 2 h in the Pla2g1b−/− mice. Previous work in our laboratory has shown that Pla2g1b−/− mice on hypercaloric diet have reduced plasma levels of lysophospholipids, the enzymatic product of Pla2g1b, compared with wild-type Pla2g1b+/+ mice on similar diet (22). Moreover, restoration of plasma lysophospholipid level in Pla2g1b−/− mice to that comparable in Pla2g1b+/+ mice by intraperitoneal injection of LPC was found to ameliorate the protective effects of Pla2g1b inactivation against glucose intolerance and postprandial hyperglycemia (22). Therefore, in the current study, we evaluated whether intraperitoneal injection of LPC to hypercaloric diet-fed Pla2g1b−/− mice prior to P407 injection would also restore the linearity of the VLDL production curve. Indeed, results showed that LPC injection also increased the rate and total amount of VLDL accumulation to levels observed in Pla2g1b+/+ mice, which were ∼2-fold greater than that observed in Pla2g1b−/− mice without LPC injection (Fig. 3). Injection of LPC also increased VLDL-triglyceride levels in Pla2g1b+/+ mice to levels above those observed in mice without LPC injection (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results indicate that LPC promotes hepatic VLDL production and that the differences in plasma lipoprotein levels and VLDL production between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice are due to reduced absorption and transport of lysophospholipids in the absence of Pla2g1b.

Fig. 3.

Effect of LPC supplementation on hepatic VLDL production by Pla2g1b−/− mice. The Pla2g1b−/− mice (open symbols) were placed on hypercaloric diet for two weeks. (A) Fasting plasma triglyceride levels were measured after 11 h fasting (t = −1 h), and then LPC was injected intraperitoneally (32 mg/kg body weight). Poloxamer 407 was injected 1 h later at the 0 h time point, and plasma samples were obtained at hourly intervals thereafter to measure plasma triglyceride levels. (B) VLDL production rates of Pla2g1b+/+ (filled bar) and Pla2g1b−/− mice without (open bar) or with LPC injection (hatched bar). (C) Plasma triglyceride levels in Pla2g1b+/+ (WT) and Pla2g1b−/− (KO) mice with or without LPC injection measured before (filled bars) and 4 h after injection of Poloxamer 407 to inhibit lipolysis (open bars). Results represent mean ± SE from at least three mice in each group. Data were analyzed in comparison with Pla2g1b+/+ mice as the control group by Student t-test *P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. ns, no significant difference.

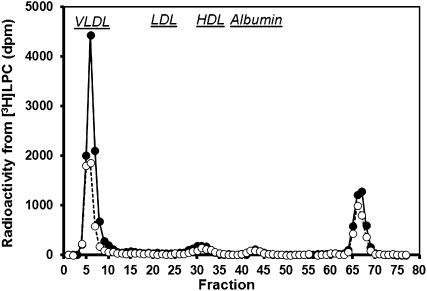

In the next set of experiments, [3H]LPC was injected into mice prior to P407 administration, and plasma was collected to determine if LPC serves as substrate for VLDL synthesis. More than half of the radioactivity recovered in plasma was found to be associated with VLDL in both Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice after 4 h, whereas the remaining radioactivity was not lipoprotein associated (Fig. 4). The amount of radioactivity from [3H]LPC incorporated into VLDL was not due to nonspecific association of the injected [3H]LPC with lipoproteins, because in vitro incubation of [3H]LPC with mouse plasma showed that most of the [3H]LPC was associated with albumin and none of the radioactivity was associated with VLDL. Moreover, the radioactivity found in VLDL after [3H]LPC injection was found in the triglyceride fraction after thin layer chromatography analysis, indicating that the LPC was used as substrate for VLDL lipid synthesis, with more radioactivity found in the VLDL fraction of Pla2g1b+/+ mice compared with Pla2g1b−/− mice (Fig. 4). Analysis of plasma apoB levels by ELISA found no difference between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice (data not shown), indicating that LPC did not change the number of particles secreted by the liver. Thus, LPC increases the production of VLDL particles with higher triglyceride content instead of increasing the number of apoB-containing lipoproteins secreted by the liver.

Fig. 4.

FPLC analysis of 3H radioactivity distribution in plasma subsequent to [3H]LPC injection. The Pla2g1b+/+ (solid symbols, n = 3) and Pla2g1b−/− (open symbols, n = 4) mice were placed on hypercaloric diet for two weeks. LPC was injected intraperitoneally (32 mg/kg body weight) after 11 h fasting (t = −1 h). Poloxamer 407 was injected 1 h later at the 0 h time point and plasma samples were obtained 4 h later (t = 4 h). Plasma was separated by FPLC, and radiolabel in each fraction was counted by liquid scintillation. Fractions where VLDL, LDL, HDL, and albumin were eluted from the column were identified based on comparison with standards as marked.

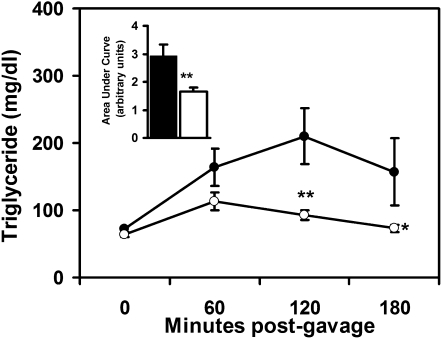

Plasma lipid levels are typically controlled by lipoprotein synthesis and catabolism. Therefore, additional experiments were performed to evaluate potential differences in triglyceride-rich lipoprotein clearance between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice. In these experiments, the mice were fasted overnight and then fed a bolus meal of olive oil by gastric gavage. Plasma triglyceride levels were monitored at hourly intervals without lipase inhibition. Results showed similar plasma triglyceride levels between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice at baseline and 60 min after oral lipid feeding. However, plasma triglyceride levels were significantly lower in Pla2g1b−/− mice compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice 120 min after lipid feeding (Fig. 5). Importantly, plasma triglyceride levels returned to their baseline fasting levels in Pla2g1b−/− mice 180 min after lipid meal, whereas plasma triglyceride levels in the wild-type Pla2g1b+/+ mice remained elevated compared with the fasting level throughout the 180 min study period (Fig. 5). AUC analysis of the data revealed a 2-fold decrease in postprandial lipidemia in the Pla2g1b−/− mice compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice (Fig. 5). As Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice are similar in lipid absorption efficiency (20, 25), the lower postprandial triglyceride levels observed in Pla2g1b−/− mice indicated their more efficient catabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice. Thus, the significant differences in fasting plasma triglyceride and cholesterol levels observed between hypercaloric diet-fed Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice were due to reduced hepatic production as well as increased clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in the Pla2g1b−/− mice.

Fig. 5.

Postprandial plasma lipid response to a bolus lipid-rich meal. The Pla2g1b+/+ (solid symbols) and Pla2g1b (−/−open symbols) mice were placed on a hypercaloric diet for three weeks. Fasting animals were fed 400 µl of olive oil by intragastric gavage. Plasma triglyceride levels were measured at hourly intervals as indicated. The inset shows AUC calculations. Results represent mean ± SE from six Pla2g1b+/+ and ten Pla2g1b−/− mice. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 versus Pla2g1b+/+ mice.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that inactivation of the intestinal digestive enzyme Pla2g1b protects mice against elevated plasma triglyceride and cholesterol levels induced by a high-fat/sucrose-supplemented (hypercaloric) diet. The protection is independent of adiposity, but it is a direct consequence of reduced hepatic VLDL production and increased triglyceride-rich lipoprotein clearance in Pla2g1b−/− mice. This conclusion is supported by data showing ∼40% decrease in hepatic VLDL production in Pla2g1b−/− mice compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice upon short-term hypercaloric diet feeding, prior to any observed differences in body weight gain. The group 1B phospholipase A2 digests phospholipids in the intestinal lumen to facilitate lipid nutrient absorption through the gastrointestinal tract (4). The products of this enzymatic reaction are nonesterified fatty acids and LPC. The difference in hepatic VLDL production between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice cannot be attributed to differences in nonesterified fatty acid absorption because other phospholipases present in the digestive tract can compensate for the absence of Pla2g1b in phospholipid digestion in mediating normal fat absorption in Pla2g1b−/− mice (25), The difference in reaction products in phospholipid hydrolysis is that lysophospholipids, which are rapidly absorbed and transported to the liver through the portal vein (23, 29), are significantly reduced in the Pla2g1b−/− mice (23). Results of the current study show LPC is a direct substrate for VLDL-triglyceride synthesis. In the absence of Pla2g1b, substrate limitation reduces VLDL-triglyceride synthesis over time. Furthermore, VLDL production can be restored by LPC supplementation. Thus, these results documented that absorption of lysophospholipid, in addition to fatty acids, also plays an important role in hepatic VLDL production.

The causative relationship of lysophospholipid absorption with VLDL synthesis is not unprecedented. Previous studies suggested that metformin decreases hepatic apoB secretion via reduction of cellular lysophosphatidylcholine (30). Although the current study showed no difference in apoB secretion between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice, lysophospholipids may contribute to hepatic VLDL production through several other mechanisms. Previous in vitro cell culture experiments illustrated that LPC can be effectively reacylated to phosphatidylcholine in hepatocytes, thereby providing the substrates necessary for VLDL synthesis under choline-deficient conditions (31). Lysophospholipids also inhibit fatty acid β-oxidation in the liver (22), thus increasing substrate availability for VLDL-triglyceride synthesis. Lysophospholipids may also provide additional substrates to promote both triglyceride and phospholipid synthesis in hepatocytes (32), thus decreasing intracellular degradation of apoB and facilitating VLDL secretion (33). Our in vivo data are consistent with the in vitro observations that reducing LPC levels limits substrate availability of VLDL synthesis and secretion. Our results showed that VLDL secretion was similar between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice during the initial h of lipolysis inhibition. The differences observed were due mainly to limited VLDL production by Pla2g1b−/− mice at later time points whereas VLDL production in Pla2g1b+/+ mice continued at a linear rate (Fig. 2B, C). The provision of LPC to the Pla2g1b−/− mice restored VLDL production rate to comparable levels as that observed in Pla2g1b+/+ mice (Fig. 3). The LPC supplied to the animals was utilized directly as lipid substrates for VLDL synthesis, and additional provision of LPC further increased VLDL production in Pla2g1b+/+ mice. Interestingly, whereas previous studies showed that the cytosolic calcium-independent phospholipase A2 expressed in the liver is important for VLDL maturation and secretion (34), the current study revealed that suppression of lysophospholipid absorption via Pla2g1b gene inactivation is also effective in suppressing VLDL synthesis.

In addition to reduced VLDL secretion, hypercaloric diet-fed Pla2g1b−/− mice also displayed enhanced clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins compared with similarly fed Pla2g1b+/+ mice. Typically, triglyceride-rich lipoprotein catabolism occurs via lipoprotein lipase-mediated hydrolysis of the lipoprotein-associated triglycerides to nonesterified fatty acids, which are then taken up by extrahepatic tissues as nutrients or stored in adipose tissues as energy reserves, and via receptor-mediated uptake of remnant lipoproteins. Although the mechanism underlying the difference in triglyceride-rich lipoprotein clearance between Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice has not been determined, a difference in lipoprotein lipase activity between these animals is unlikely. Increased lipoprotein lipase activities in adipose tissues and muscle/heart to facilitate fat uptake from triglyceride-rich lipoproteins are known to promote obesity and insulin resistance, respectively (35, 36). However, the Pla2g1b−/− mice are more resistant to diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance (20, 23). In contrast, the increase in hepatic fatty acid oxidation (22) and reduced plasma lipid levels observed in Pla2g1b−/− mice suggests that these animals are more resistant to diet-induced suppression of LDL receptor expression in the liver. Thus, the accelerated plasma clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in hypercaloric diet-fed Pla2g1b−/− mice is likely due to increased receptor-mediated clearance by the liver. Taken together, these results indicate that Pla2g1b inactivation reduces diet-induced hyperlipidemia by decreasing VLDL production and accelerating the clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins; hence, pharmacological inhibition of phospholipase A2 activity in the digestive tract may be sufficient to reduce diet-induced hyperlipidemia in addition to the previously reported beneficial effects on obesity and diabetes (21).

Results of the current study also showed lower plasma HDL-cholesterol levels in hypercaloric diet-fed Pla2g1b−/− mice compared with Pla2g1b+/+ mice. At first glance, these results may suggest an undesirable effect of Pla2g1b inhibition. However, note that Pla2g1b inactivation did not reduce HDL-cholesterol levels, as comparable HDL-cholesterol levels were observed between hypercaloric diet-fed Pla2g1b−/− mice and chow-fed Pla2g1b+/+ and Pla2g1b−/− mice. The Pla2g1b−/− mice were insensitive to the increase in HDL-cholesterol levels after chronic feeding of a hypercaloric diet, suggesting that these animals were not sensing the increased supply of dietary lipids with lipid metabolism (current study) and glucose metabolism (23) similar to those observed in chow-fed animals. In fact, the dietary lipids were readily oxidized in the liver and not available to alter the metabolism in Pla2g1b−/− mice (22). The ability of Pla2g1b inactivation to reduce the synthesis of VLDL, the precursor lipoprotein of the atherogenic LDL, while sustaining normal HDL levels has direct clinical implications for targeted improvement of plasma lipoprotein profile in humans.

Footnotes

- AUC

- area under the curve

- LPC

- lysophosphatidylcholine

- P407

- poloxamer 407

- Pla2g1b

- group 1B phospholipase A2

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant DK-069967 (D.Y.H.) and supplemental Grant DK-069967-04S1 to promote diversity in a health-related research program (N.I.H.) and by American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship Grant 11PRE7310047 (N.I.H.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other granting agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moller D. E., Kaufman K. D. 2005. Metabolic syndrome: a clinical and molecular perspective. Annu. Rev. Med. 56: 45–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Després J. P., Lemieux I. 2006. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 444: 881–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel 2002. Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 106: 3143–3421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey M. C., Small D. M., Bliss C. M. 1983. Lipid digestion and absorption. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 45: 651–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui D. Y., Howles P. N. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of cholesterol absorption and transport. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16: 183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansbach C. M., Siddiqi S. A. 2010. The biogenesis of chylomicrons. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72: 315–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gesta S., Tseng Y-H., Kahn C. R. 2007. Developmental origin of fat: tracking obesity to its source. Cell. 131: 242–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahley R. W., Hussain M. M. 1991. Chylomicron and chylomicron remnant catabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2: 170–176 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iozzo P., Bucci M., Roivainen A., Nagren K., Jarvisalo M. J., Kiss J., Guiducci L., Fielding B., Naum A. G., Borra R., et al. 2010. Fatty acid metabolism in the liver, measured by positron emission tomography, is increased in obese individuals. Gastroenterology. 139: 846–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen S., Guo Z., Johnson C. M., Hensrud D. D., Jensen M. D. 2004. Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 113: 1582–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis G. F. 1997. Fatty acid regulation of very low density lipoprotein production. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 8: 146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berge R. K., Tronstad K. J., Berge K., Rost T. H., Wergedahl H., Gudbrandsen O. A., Skorve J. 2005. The metabolic syndrome and the hepatic fatty acid drainage hypothesis. Biochimie. 87: 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotamisligil G. S., Shargill N. S., Spiegelman B. M. 1993. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 259: 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisberg S. P., McCann D., Desai M., Rosenbaum M., Leibel R. L., Ferrante A. W., Jr 2003. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 112: 1796–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olefsky J. M., Glass C. K. 2010. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72: 219–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unger R. H. 2003. Minireview: weapons of lean body mass destruction: the role of ectopic lipids in the metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 144: 5159–5165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pérusse L., Rice T., Chagnon Y. C., Despres J-P., Lemieux S., Roy S., Lacaille M., Ho-Kim M-A., Chagnon M., Province M. A., et al. 2001. A genome-wide scan for abdominal fat assessed by computed tomography in the Quebec family study. Diabetes. 50: 614–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chagnon Y. C., Merette C., Bouchard R. H., Emond C., Roy M. A., Maziade M. 2004. A genome wide linkage study of obesity as secondary effect of antipsychotics in multigenerational families of eastern Quebec affected by psychoses. Mol. Psychiatry. 9: 1067–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson S. G., Adam G., Langdown M., Reneland R., Braun A., Andrew T., Surdulescu G. L., Norberg M., Dudbridge F., Reed P. W., et al. 2006. Linkage and potential association of obesity-related phenotypes with two genes on chromosome 12q24 in a female dizygous twin cohort. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 14: 340–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huggins K. W., Boileau A. C., Hui D. Y. 2002. Protection against diet-induced obesity and obesity-related insulin resistance in Group 1B PLA2-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 283: E994–E1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui D. Y., Cope M. J., Labonté E. D., Chang H-T., Shao J., Goka E., Abousalham A., Charmot D., Buysse J. 2009. The phospholipase A2 inhibitor methyl indoxam suppresses diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 157: 1263–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labonté E. D., Pfluger P. T., Cash J. G., Kuhel D. G., Roja J. C., Magness D. P., Jandacek R. J., Tschop M. H., Hui D. Y. 2010. Postprandial lysophospholipid suppresses hepatic fatty acid oxidation: the molecular link between group 1B phospholipase A2 and diet-induced obesity. FASEB J. 24: 2516–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labonté E. D., Kirby R. J., Schildmeyer N. M., Cannon A. M., Huggins K. W., Hui D. Y. 2006. Group 1B phospholipase A2-mediated lysophospholipid absorption directly contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 55: 935–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richmond B. L., Hui D. Y. 2000. Molecular structure and tissue-specific expression of the mouse pancreatic phospholipase A2 gene. Gene. 244: 65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richmond B. L., Boileau A. C., Zheng S., Huggins K. W., Granholm N. A., Tso P., Hui D. Y. 2001. Compensatory phospholipid digestion is required for cholesterol absorption in pancreatic phospholipase A2 deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 120: 1193–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerdes L. U., Gerdes C., Klausen I. C., Faegeman O. 1992. Generation of analytic plasma lipoprotein profiles using prepacked superose 6B columns. Clin. Chim. Acta. 205: 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millar J. S., Cromley D. A., McCoy M. G., Rader D. J., Billheimer J. T. 2005. Determining hepatic triglyceride production in mice: comparison of poloxamer 407 with Triton WR-1339. J. Lipid Res. 46: 2023–2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayek T., Ito Y., Azrolan N., Verdery R. B., Aalto-Setala K., Walsh A., Breslow J. L. 1993. Dietary fat increases high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels both by increasing the transport rates and decreasing the fractional catabolic rates of HDL cholesteryl ester and apolipoprotein A-I. J. Clin. Invest. 91: 1665–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portman O. W., Soltys P., Alexander M., Osuga T. 1970. Metabolism of lysolecithin in vivo: effects of hyperlipemia and atherosclerosis in squirrel monkeys. J. Lipid Res. 11: 596–604 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wanninger J., Neumeier M., Weigert J., Liebisch G., Weiss T. S., Schaffler A., Aslanidis C., Schmitz G., Scholmerich J., Buechler C. 2008. Metformin reduces cellular lysophosphatidylcholine and thereby may lower apolipoprotein B secretion in primary human hepatocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1781: 321–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson B. S., Yao Z., Baisted D. J., Vance D. E. 1989. Lysophosphatidylcholine metabolism and lipoprotein secretion by cultured rat hepatocytes deficient in choline. Biochem. J. 260: 207–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiggins D., Gibbons G. F. 1996. Origin of hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein triacylglycerol: the contribution of cellular phospholipid. Biochem. J. 320: 673–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Z., Luchoomun J., Bakillah A., Hussain M. M. 1998. Lysophosphatidylcholine increases apolipoprotein B secretion by enhancing lipid synthesis and decreasing its intracellular degradation in HepG2 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1391: 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tran K., Wang Y., DeLong C. J., Cui Z., Yao Z. 2000. The assembly of very low density lipoproteins in rat hepatoma McA-RH7777 cells is inhibited by phospholipase A2 antagonists. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 25023–25030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H., Eckel R. H. 2009. Lipoprotein lipase: from gene to obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297: E271–E288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voshol P. J., Rensen P. C., van Dijk K. W., Romijn J. A., Havekes L. M. 2009. Effect of plasma triglyceride metabolism on lipid storage in adipose tissue: studies using genetically engineered mouse models. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1791: 479–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]