Abstract

PURPOSE

Socioeconomic position (SEP) has been shown to be related to obesity and weight gain, especially among women. It is unclear how different measures of socioeconomic position may impact weight gain over long periods of time, and whether the effect of different measures vary by gender and age group. We examined the effect of childhood socioeconomic position, education, occupation, and log household income on a measure of weight gain using individual growth mixed regression models and Alameda County Study data collected over thirty four years(1965–1999).

METHODS

Analyses were performed in four groups stratified by gender and age at baseline: women, 17–30 years (n = 945) and 31–40 years (n = 712); men, 17–30 years (n = 766) and 31–40 years (n = 608).

RESULTS

Low childhood SEP was associated with increased weight gain among women 17–30 (0.13 kg/year, p < 0.001). Low educational status was associated with increased weight gain among women 17–30 (0.14 kg/year, p = 0.030), 31–40 (0.14 kg/year, p = 0.014), and men 17–30 (0.20 kg/year, p = 0.001).

CONCLUSION

Log household income was inversely associated with weight gain among men 31–40 (−0.10 kg/yr, p = 0.16). Long-term weight gain in adulthood is associated with childhood SEP and education in women and education and income in men.

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with obesity in women in the United States and most of the developed world, whereas studies of American men have yielded conflicting results (1). Much of the evidence for men and women has been derived from cross-sectional studies. A recently published review of longitudinal studies suggests that socioeconomic position (SEP), especially as measured by occupation/employment status, is associated with weight gain in both men and women (2).

Education, occupation, and income may influence weight gain in different ways. For example, those that are better educated may make more effective choices about food and physical activity because they have acquired more knowledge about nutrition and exercise than the less educated. Choices about diet and exercise may depend on the cost of healthy food and access to places to exercise (3). Occupation may influence weight change via the greater physical activity required of many blue-collar jobs It is difficult to test these various pathways, and many other possibilities, but a starting point is to examine the relative and independent contribution of education, income, and occupation to weight gain.

It may be important to also consider childhood SEP because it has been shown to be associated with adult obesity (4–9), possibly through an impact on weight gain in childhood. Some studies do suggest that there may be a continuing effect of childhood SEP on weight gain in adulthood particularly among women (10–12).

The aims of this study are (i) to determine the relative and independent contribution of different measures of socioeconomic position to weight gain in adulthood and (ii) to determine whether their impact varies by age and gender. This study makes use of a unique opportunity in that it uses information on weight collected over the course of 34 years and includes four measures of SEP; most previous studies were of much shorter duration and only included one or two measures of SEP. Previous analyses of the Alameda County data using these same SEP measures indicated that taken together these measures explained much of the difference in weight gain among African American and white women (13).

The associations of childhood SEP, education, occupation, and income with weight gain were explored; with and without simultaneous adjustment for each other in men and women in two different age groups. We hypothesized that education would have the strongest effect of all the measures because of its direct influence and because of its association with childhood socioeconomic circumstances and later occupation and income; that the younger age group (age 17–30 years) would experience a stronger effect of childhood SEP than the older age group (age 31–40 years); and that each measure would have stronger effect on weight gain in women than men.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The Alameda County Study is a longitudinal, population-based cohort study begun in 1965 of 6928 adults (86% of eligible) derived from a stratified, random household sample (14–16). All adults ages 18 or older (17 if married) in a household were eligible for inclusion in the study. Follow-up questionnaires were administered by mail in 1974, 1983, 1994, and 1999. Subjects were asked to respond to questions about their mental and physical health, SEP, and social relationships. The sample size in 1974, 1983 (50% sample), 1994 and 1999, respectively, was 4864 (85% of eligible), 1799 (87% of eligible), 2730 (93% of eligible), and 2123 (95% of eligible). More details of the sampling process are reported elsewhere (15). For this study, weight was included from all waves that a participant provided the information. Because of a limitation of the statistical modeling procedure, socioeconomic and adjustment variables used in the analyses represent levels reported at baseline (1965) only.

The analyses were restricted to participants who were age 40 years or younger at baseline (n = 3206). Older respondents were excluded to minimize problems of selective survival related to weight and to limit the population to one that was more likely to be gaining weight (weight loss is common in the elderly) (17). Participants who were missing baseline information on any covariates used in the statistical models (n = 148, 4.6%) were excluded from the analyses. Respondents in the older age group (ages 31–40 years, see analysis section) whose reported occupation was in the students/unemployed/other category at baseline (n = 27, 0.8%) also were excluded because their number was too small for a meaningful analysis. This left a total sample of 3031 (94.5% of those eligible). Those excluded from the analysis were more likely to be nonwhite, less educated, employed in a blue-collar occupation, poorer, shorter, and to have larger families.

Outcome Measure

Weight was self-reported in pounds, which were converted to kilograms for the analyses. Differences in weight gain by socioeconomic measures were examined.

Socioeconomic Variables

Childhood SEP

Childhood SEP was categorized based on father's occupation. When occupation information was missing, father's education was used. Father's occupation was available for 93.5% of the respondents. Low childhood SEP was assigned to respondents reporting a father with a blue-collar occupation, or an education of high school or less. Participants with a high childhood SEP were those whose father had a white-collar occupation, or had more than a high school degree.

Education

Years of education originally were reported as a continuous variable. For purposes of the analyses, categories were created to correspond to levels of certification: less than high school (<12 years), high school or some college (12–15 years), and college graduate (16 years).

Occupation

Occupation was classified (according to 1960 U.S census guidelines) as white-collar, blue-collar, keeping house (women only), or student/unemployed/other (age 17–30 years at baseline only).

Income

Household income was originally reported in intervals. Exact dollar income values were imputed using the 1965 Current Population Survey (CPS), a national representative sample of U.S. households (18). Income was imputed because 117 subjects (4.3%) did not report income, and analyses with missing information are subject to bias (19). A set of covariates (age, gender, race, education, marital status, number of household members, and income interval) present in both the Alameda County Study and the CPS was used to impute an income value using a series of regression models, using the same process described by Raghunathan et al. (20). The imputation was bound within reported income categories for ACS respondents with non-missing income information.

The CPS income distribution was used to create the categorical boundary for missing income data. This technique assumed data were missing at random with the joint distribution fully conditioned on all observed information. Approximations for missing income data were generated using separate regression models that created variables using non-missing or other imputed variables as covariates. The process was repeated until all imputed values converged. This imputation process has been shown to increase efficiency and provide unbiased risk estimates owing to its comprehensive use of all available data (21). The continuous imputed income was then log transformed.

Adjustment Variables

All models contained an adjustment for the respondent's age, race (black, white, other), and self-reported height (cm) and weight at baseline. Baseline weight was adjusted for by the inclusion of an intercept term in the models (see statistical analysis section below). An adjustment for height was needed because height is related to weight and may also be related to childhood socioeconomic conditions (22). All models containing household income also were adjusted for household size.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were done using PROC MIXED in SAS v. 8.0. A linear individual growth regression model was used to determine the effect of exposures on weight change slope. Random effects were calculated for intercept and time. The statistical model is:

Wt is body weight in kilograms at time t, β0i is the term for baseline weight, β1,i is the term for change in body weight from baseline until time t. SEP is the socioeconomic variable of interest and x1-p are covariates. ∊it, η0i, and η1i are error terms. All variables including adjustment variables were thus included in each model as a main effect term and as an interaction with time term. Linearity of the weight data was checked by visually comparing a plot of the line generated by the model to the average weight of subjects at each wave of data collection. All respondents with baseline weight data contributed to the intercept terms while respondents with at least two data points contributed to the slope terms.

The study population was divided into two age groups (age 17–30 years at baseline, age 31–40 years at baseline) for the analyses to determine if the dynamics of SEP differed in the two age groups. All analyses were also stratified by gender. The first set of analyses modeled the effect of each of the SEP variables separately, with adjustment for age, height, and race. A model containing all the SEP variables simultaneously was also estimated.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 provides the baseline distribution of the variables used in the analyses for each of the age/gender groups. The sample was predominately white, with the remainder of subjects nearly equally split between blacks and those of other races. Low childhood SEP was more common than high in all age/gender groups. Men were more likely to have a college education than women. Men in the older group were more likely to report white-collar jobs than blue-collar jobs; in the younger group, it was the reverse. This could be the result of the large number of younger men in the unemployed/student/other category who, based on 1974 occupational status (91.7% white-collar of those with 1974 data), were most likely students. Among women, blue-collar status was relatively uncommon. Large percentages of women reported keeping house and not working for income in 1965. Household income was greater in the older group than in the younger group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants aged 17–40 in 1965 in the Alameda County Study.

| Sex |

Men |

Women |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age group | 17–30 | 31–40 | 17–30 | 31–40 |

| N | 766 | 608 | 945 | 712 |

| Age, years* | 25.31 (3.08) | 35.59 (2.84) | 24.49 (3.17) | 35.78 (2.89) |

| Race** | ||||

| Black | 75 (9.79) | 57 (9.38) | 96 (10.16) | 96 (13.48) |

| White | 619 (80.81) | 485 (79.77) | 753 (79.68) | 522 (73.31) |

| Other | 72 (9.40) | 66 (10.86) | 96 (10.16) | 94 (13.20) |

| Height, cm* | 178.64 (7.59) | 177.57 (7.69) | 163.22 (7.14) | 162.70 (6.89) |

| Family size* | 2.75 (1.55) | 4.02 (1.71) | 3.07 (1.56) | 4.20 (1.77) |

| Childhood SEP** | ||||

| High | 350 (45.69) | 270 (44.41) | 454 (48.04) | 301 (42.28) |

| Low | 416 (54.31) | 338 (55.59) | 491 (51.96) | 411 (57.72) |

| Education** | ||||

| <12 years | 102 (13.32) | 169 (27.80) | 171 (18.10) | 203 (28.51) |

| 12–15 years | 455 (59.40) | 276 (45.39) | 606 (64.13) | 428 (60.11) |

| 16+ years | 209 (27.28) | 163 (26.81) | 168 (17.78) | 81 (11.38) |

| Occupation** | ||||

| Blue collar | 323 (42.17) | 281 (46.22) | 73 (7.72) | 100 (14.04) |

| White collar | 266 (34.73) | 327 (53.78) | 351 (37.14) | 207 (29.07) |

| Keeping house | n/a | n/a | 426 (45.08) | 405 (56.88) |

| Student /unemployed /other | 177 (23.11) | 95 (10.05) | ||

| Income, 1999 $* | 47,000 (35,406) | 56,582 (34,412) | 48,615 (36,596) | 55,249 (39,779) |

Mean and standard deviation are presented for continuous variables

number and proportion are presented for categorical variables

Weight Gain by Gender and Age

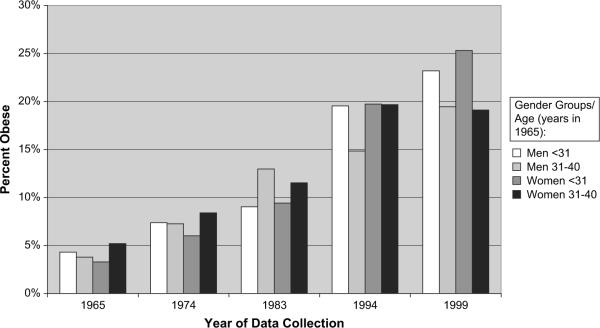

Subjects tended to gain weight regardless of their SEP. Women tended to gain more than men, and the younger group tended to gain more than the older. Men who were younger than 30 years of age at baseline had an average weight at baseline of 76.11 kg (SD = 10.89) and gained an average of 0.35 kg/year (SD = 0.21). Women in the same age group weighed 57.51 kg (SD = 9.68) on average at baseline and gained an average of 0.47 kg/year (SD = 0.29). Men ages 31–40 years at baseline began the study at an average of 77.67 kg (SD = 10.73) and gained 0.21 kg/year (SD = 0.20). Women in the older age group weighed an average of 59.93 kg (SD = 11.37) at baseline and gained 0.29 kg/year (SD = 0.21). The weight gain slopes represent substantial amounts of weight if multiplied by the potential 34-year follow-up of the study: Men ≤30 years = 11.90 kg; men 31–40 years = 7.14 kg; women ≤30 years = 15.98 kg; women 31–40 years = 9.86 kg. The percentage of obesity (BMI ≥ 30) in each group also increased substantially for each of the gender/age groups over time (see Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of obesity at each wave of data collection in the Alameda County Study by gender/age group.

Weight Gain by SEP

Table 2 presents the results for the analyses of SEP on weight change. Childhood SEP had a significant effect only in women younger than 31 years with a 0.13 kg/year (p < 0.001) greater weight gain in those with low childhood SEP compared with those with high childhood SEP. In general, education tended to have the strongest effects on weight gain, with significant effects in three of the groups (≤high school vs. college: women 17–30 years: 0.14 kg/year, p = 0.030; women 31–40 years: 0.14 kg/year, p = 0.014, men 17–40 years: 0.20 kg/year, p = 0.001), and near significant results in men aged 31–40 years (0.09 kg/year, p = 0.062). Furthermore, the relationship for education was graded for all groups; those with less than high school education gained more than those with a high school education, who in turn gained more than those with a college education. Occupation did not have any effect on weight change in any group. Income was inversely related to weight gain only in the older group of men (−0.10 kg/year/log unit, p = 0.016).

Table 2.

Differences in weight gain by Life-course SEP. Results derived from mixed models of participants aged 17–40 in 1965 in the Alameda County Study

| Age < 30 years at baseline |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n=766) |

Women (n=945) |

|||||||

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

| Weight gain diff. (kg/yr) | p value | Weight gain diff. (kg/yr) | p value | Weight gain diff. (kg/yr) | p value | Weight gain diff (kg/yr) | p value | |

| Childhood SEP: | ||||||||

| Low vs. High | +0.05 | 0.181 | −0.01 | 0.862 | +0.13 | < 0.001 | +0.09 | 0.020 |

| Education: | ||||||||

| High School Vs. College < | + 0.11 | 0.003 | +0.07 | 0.117 | +0.11 | 0.014 | +0.03 | 0.531 |

| High School Vs. College | +0.20 | 0.001 | +0.14 | 0.056 | +0.14 | 0.030 | −0.00 | 0.954 |

| Occupation: | ||||||||

| Blue Collar Vs. White Collar | +0.05 | 0.206 | −0.01 | 0.770 | +0.05 | 0.579 | +0.01 | 0.882 |

| Keeping house Vs White Collar | −0.01 | 0.831 | −0.08 | 0.090 | ||||

| 1 log unit change HH income | −0.01 | 0.687 | −0.02 | 0.464 | −0.00 | 0.898 | −0.02 | 0.574 |

| Age = 31–40 years at baseline |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n=608) |

Women (n=712) |

|||||||

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

| Weight gain diff. (kg/yr) | p value | Weight gain diff. (kg/yr) | p value | Weight gain diff. (kg/yr) | p value | Weight gain diff. (kg/yr) | p value | |

| Childhood SEP: | ||||||||

| Low vs. High | +0.01 | 0.698 | −0.01 | 0.801 | +0.05 | 0.099 | +0.03 | 0.454 |

| Education: | ||||||||

| High School Vs. College < | +0.07 | 0.081 | +0.06 | 0.205 | +0.08 | 0.105 | +0.05 | 0.274 |

| High School Vs. College | +0.09 | 0.062 | +0.07 | 0.247 | +0.14 | 0.014 | +0.10 | 0.098 |

| Occupation: | ||||||||

| Blue Collar Vs. White Collar | +0.05 | 0.163 | −0.00 | 0.919 | +0.05 | 0.402 | +0.03 | 0.651 |

| Keeping house Vs White Collar | +0.00 | 0.943 | −0.03 | 0.407 | ||||

| 1 log unit change HH income | −0.10 | 0.016 | −0.08 | 0.056 | −0.04 | 0.156 | −0.03 | 0.392 |

Model 1: age, race, height, childhood SEP or education or occupation or income.

Model 2: age, race, height, childhood SEP, education, occupation, income.

p-value of t-test from mixed model, testing Ho: value of coefficient=0.

Associations were attenuated when all SEP measures were included in the model simultaneously (Table 2). Childhood SEP remained significant for the younger women (0.09 kg/year, p = 0.02). Education was the strongest factor for the younger men (less than high school vs. college: 0.14 kg/year, p = 0.056) and older women (less than high school vs. college: 0.10 kg/year, p = 0.098) and the only factor that approached significance at α=0.05 in these two groups. Income was the strongest predictor and borderline significant for the older men (−0.08 kg/year/log unit, p = 0.056).

DISCUSSION

Our first hypothesis that education would have the strongest effect on adult weight gain was largely supported, as there was a significant or near-significant effect of education in all age/gender groups. Childhood SEP impacted weight gain in the younger group of women but not men, thus lending only partial support to our second hypothesis. Income only impacted the older group of men. Occupation did not impact weight gain in any group. Taken together, these findings suggest a qualitatively (not quantitatively as hypothesized) different SEP-weight gain pathway for men and women. Women are impacted at younger ages by their childhood circumstances and later by their educational attainment. On the other hand men are first impacted by their educational attainment and later by their income.

The importance of childhood SEP in women (but not men) could be the result of different SEP activity patterns that may exist in boys and girls; unfortunately, few if any studies have examined this issue. Physical activity patterns developed early in life may continue into adulthood and thus continue to impact weight (23). Adult leisure-time physical activity did vary by SEP in the ACS data, but the association was nearly the same for men and women. It is also possible that diet could be patterned by SEP in girls but not boys, and thus causes SEP differences in weight gain. Perhaps girls from families with higher SEP were encouraged to diet more than girls from lower SEP, whereas boys of any SEP were not encouraged to restrict calories. One study of recent high school graduates found just such a SEP pattern of dieting by gender (24).

The importance of income in men, but not women suggests that men are more influenced by a “price pathway.” When making decisions on weight impacting behaviors, men may be more influenced by the financial costs of food and staying physically active (gym memberships and exercise equipment) than women.

The lack of an association with occupation also may suggest processes influencing body weight. One explanation for the lack of an association is that the higher workplace physical activity of blue-collar workers may counterbalance lower physical activity and poorer eating habits (“social norms pathway”) outside the workplace. It is also possible that the measure of occupation was not specific enough. For instance, the blue-collar category included occupations with vastly different physical activity requirements, such as construction workers and bus drivers. Although Ball and Crawford's review of the SEP-weight change literature found occupation the measure most likely to be associated with weight gain, it should be noted that most of the reviewed studies included different measures of occupation or used employment status, included different age ranges, were usually of shorter duration, and did not always include adjustments for other measures of SEP (2).

There are several limitations of the analyses. The use of self-reported weight is an obvious limitation. Two studies examining the validity of self-reported weight found similar results. Self-reported weight was highly correlated with measured weight (rs = 0.99) (25, 26). Although the correlation was high, the tendency was for both men and women to underreport their weight. Men with higher education tended to underreport weight to a greater degree than lower educated men. A reporting bias of less than a 1 kg between low and high education was found in the aforementioned studies. This amount cannot fully account for the results observed in this study, and if people tend to underreport by the same amount at each wave the slope estimates should not be affected.

Childhood SEP data were collected retrospectively and are therefore subject to recall bias. The other exposure variables are limited by using only baseline values; this is a limitation of individual growth models. Baseline educational attainment may not be a true reflection of lifetime educational attainment in the younger group, since many in this group had not completed their educations by 1965. Any findings influenced by this type of misclassification should be biased toward the null. Presumably the lifetime weight gain experience of those who were still students in 1965 should mirror that of those who had already completed their education in 1965 to the same level eventually achieved by the students. Students were assigned to a lower educational category at baseline than they would eventually achieve. The category the students were assigned to at baseline should have a lower average weight gain than if the students were assigned to a higher education category. In actuality, the education results for the younger group were rather similar to the results for the older group where such misclassification is less of a concern. Furthermore, when 1974 educational level was entered into the models the results did not change significantly for the younger age group.

The results do not clarify what factors are responsible for the observed socioeconomic associations. Few studies to date have examined potential mediating factors. One study by Martikainen and Marmot found that cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity and diet explained some of the socioeconomic association with weight gain over the course of 25 years (27). An exploration of the causal pathway was beyond the scope of this paper, further examination of the Alameda County Study data will clarify if marital status, children, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and depression are in the pathway connecting SEP and long-term weight gain. Further studies should also examine people's motivation for eating/ physical activity patterns to confirm or refute the existence of the information, price, occupational physical activity, and social norms SEP-weight gain pathways.

The findings of this study can inform obesity-prevention programs. Prevention programs need to begin early in life, particularly among girls. Educational and health literacy campaigns may impact both men and women, while financial incentives to eat well or exercise may be more effective for men.

Selected Abbreviations and Acronyms

- SEP

socioeconomic position

REFERENCES

- 1.Sobal J, Stunkard AJ. Socioeconomic status and obesity: A review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;05:260–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball K, Crawford D. Socioeconomic status and weight change in adults: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1987–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drewnowski A, Darmon N. The economics of obesity: dietary energy density and energy cost. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1 Suppl):265s–273s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.265S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braddon FE, Rodgers B, Wadsworth ME, Davies JM. Onset of obesity in a 36 year birth cohort study. Br Med J. 1986;293:299–303. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6542.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laitinen J, Power C, Jarvelin MR. Family social class, maternal body mass index, childhood body mass index, and age at menarche as predictors of adult obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:287–294. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power C, Graham H, Due P, et al. The Contribution of childhood and adult socioeconomic position to adult obesity and smoking behavior: an international comparison. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:335–344. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James SA, Fowler-Brown A, Raghunathan TE, Van Hoewyk J. Life-course socioeconomic position and obesity in African American Women: the Pitt County Study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:554–560. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ball K, Mishra GD. Whose socioeconomic status influences a woman's obesity risk: her mother's, her father's, or her own? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:131–138. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons TJ, Power C, Logan S, Summerbell CD. Childhood predictors of adult obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(Suppl 8):S1–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahmann PH, Lissner L, Gullberg B, et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with long-term weight gain, current body fatness and central adiposity in Swedish women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;26:685–594. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenlund KJ, Liu K, Dyer AR, Kiefe CI, Burke GL, Yunis C. Body mass index in young adults: Associations with paremtal body size and education in the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:480–485. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.4.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy R, Wadsworth M, Kuh D. The influence of childhood weight and socioeconomic status on change in adult body mass index in a British national birth cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:725–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baltrus PT, Lynch JW, Everson-Rose SA, Ragunathan TE, Kaplan GA. Race/ethnicity, life-course socioeconomic position, and body weight trajectories over 34 years: the Alameda County Study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1595–1601. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.046292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochstim JR. Health and ways of living. In: Kessler II, Levin ML, editors. The Community as an Epidemiologic Laboratory. Johns Hopkins Press; Baltimore: 1970. pp. 149–175. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berkman L, Breslow L. Health and Ways of Living: The Alameda County Study. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan GA. Health and aging in the Alameda County Study. In: Schaie KW, Blazer DG, House JSK, editors. Aging, Health Behaviors, and Health Outcomes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace JI, Schwartz RS, LaCroix AZ, et al. Involuntary weight loss in older outpatients: incidence and clinical significance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Current Population Survey–Design and Methodology. Bureau of Labor Statistics/ US Census Bureau; Washington DC: 2002. Technical paper 63RV. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghunathan TE. What do we do with missing data? Some options for analysis of incomplete data. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:99–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.102802.124410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, et al. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27:83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raghunathan TE, Siscovick DS. A multiple-imputation analysis of a case-control study of the risk of primary cardiac arrest among pharmacologically treated hypertensives. Appl Stat. 1996;45:335–352. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Power C, Manor O, Li L. Are inequalities in height underestimated by adult social position? Effects of changing social structure and height selection in a cohort study. Br Med J. 2002;325:131–134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7356.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alfano CM, Klesges RC, Murray DM, et al. History of sport participation in relation to obesity and related health behaviors in women. Prev Med. 2002;34:82–89. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drewnowski A, Kurth CL, Krahn DD. Body weight and dieting in adolescence: impact of socioeconomic status. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:61–65. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199407)16:1<61::aid-eat2260160106>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart AL. The reliability and validity of self-reported weight and height. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35:295–309. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffery RW. Bias in reported body weight as a function of education, occupation, health and weight concern. Addict Behav. 1996;21:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martikainen PT, Marmot MG. Socioeconomic differences in weight gain and determinants and consequences of coronary risk factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:719–726. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]