Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transforms B lymphocytes through the expression of the latent viral proteins EBNA and latent membrane protein (LMP). Recently, it has become apparent that microRNAs (miRNAs) also contribute to EBV's oncogenic properties; recombinant EBVs that lack the BHRF1 miRNA cluster display a reduced ability to transform B lymphocytes in vitro. Furthermore, infected cells evince a marked upregulation of the EBNA genes. Using recombinant viruses that lack only one member of the cluster, we now show that all three BHRF1 miRNAs contribute to B-cell transformation. Recombinants that lacked miR-BHRF1-2 or miR-BHRF1-3 displayed enhanced EBNA expression initiated at the Cp and Wp promoters. Interestingly, we find that the deletion of miR-BHRF1-2 reduced the expression level of miR-BHRF1-3 and possibly that of miR-BHRF1-1, demonstrating that the expression of one miRNA can potentiate the expression of other miRNAs located in the same cluster. Therefore, the phenotypic traits of the miR-BHRF1-2 null mutant could result partly from reduced miR-BHRF1-1 and miR-BHRF1-3 expression levels. Nevertheless, using an miR-BHRF1-1 and miR-BHRF1-3 double mutant, we could directly assess and confirm the contribution of miR-BHRF1-2 to B-cell transformation. Furthermore, we found that the potentiating effect of miR-BHRF1-2 on miR-BHRF1-3 synthesis can be reproduced with simple expression plasmids, provided that both miRNAs are processed from the same transcript. Therefore, this enhancing effect does not result from an idiosyncrasy of the EBV genome but rather reflects a general property of these miRNAs. This study highlights the advantages of arranging the BHRF1 miRNAs in clusters: it allows the synchronous and synergistic expression of genetic elements that cooperate to transform their target cells.

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infects and persists in a large majority of the world's human population. Primary infection is usually clinically silent but can give rise to an infectious mononucleosis (IM) syndrome if the first contact with the virus is delayed until adolescence (28). During IM, a potent T-cell immune response against EBV-infected B cells is characteristically observed. In patients with inherited or acquired immunodeficiencies, the ability of the virus to transform B cells can result in the development of B-cell lymphoproliferation. Crucially, the transforming potential of EBV can be reproduced by simply exposing primary B cells to the virus in vitro. Decades of work have established that B-cell transformation requires the expression of the latent proteins, two families of viral proteins known as the latent membrane proteins (LMPs) and the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens (EBNAs) (28). Among these proteins, the viral oncogene LMP1 and EBNA2 have been found to be central to the oncogenic potential of EBV (28). More recently, we and others have investigated the role played by microRNAs (miRNAs) during EBV-mediated B-cell transformation (10, 29). MiRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that bind to fully or partially complementary sequences from mRNAs through their seed sequences; this binding usually impairs translation and reduces the stability of the targeted mRNAs (3). EBVs that lack the BHRF1 miRNA cluster, a group of three miRNAs that includes two miRNAs located in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the BHRF1 gene and one miRNA present in the immediate vicinity of the BHRF1 mRNA transcription start site (24) (Fig. 1), have a reduced ability to transform B cells (10, 29). Although already discernible in infected bulk cultures, the contribution of the BHRF1 miRNA cluster to B-cell growth became especially obvious in infection experiments performed with low B-cell densities; the mutant viruses were ≥20 times less transforming than the wild-type (wt) controls (10). The BHRF1 miRNA cluster therefore appears to strongly potentiate the transforming properties of EBV. The growth defects displayed by B cells infected with the BHRF1 cluster-negative virus correlated with reduced entry into the S phase and a relative accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase (10, 29). These phenotypic traits suggest that the BHRF1 miRNA cluster downregulates genes that antagonize or prevent B-cell growth. Furthermore, there was evidence of increased apoptosis in B cells infected with a recombinant virus that lacks the three BHRF1 miRNAs (29). The deletion of the BHRF1 miRNAs also had profound consequences for the viral gene expression pattern; B-cell lines generated with the null EBV mutant produced between 15 and 30 times more latent transcripts initiated at the viral Cp or Wp promoter than the controls (10). These mRNAs encode all the EBNA proteins, and increases in their levels correlated with the enhanced synthesis of these proteins. This was particularly striking for EBNA-LP, whose expression level correlates directly with the number of Cp- and Wp-initiated transcripts (17).

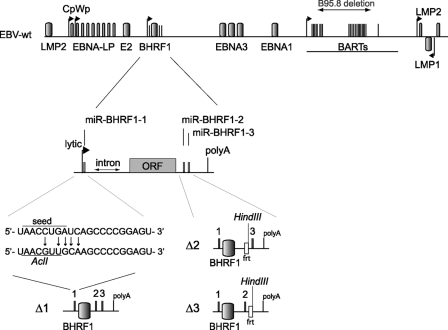

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the construction of the single and double BHRF1 miRNA viral mutants. The top panel shows a schematic representing the EBV wild-type genome. Shown are the latent EBV genes, the two promoters that initiate the latent EBNA transcripts (Cp and Wp), the lytic BHRF1 promoter, the BART regions, and the deletion in EBV strain B95.8. The EBV BHRF1 and BART microRNAs are presented as black bars. The middle panel shows an enlargement of the BHRF1 gene locus. We obtained the Δ1 mutant by mutating the miR-BHRF1-1 seed region (arrows) (bottom); this resulted in the introduction of an additional AclI restriction site that allowed the screening of the properly recombined mutants. MiR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3 were deleted by exchanging the mature miRNA sequences for a kanamycin resistance cassette flanked by flip recombinase target (Frt) sites. The excision of the kanamycin cassette by Flp recombinase led to the replacement of these miRNAs with an Frt site that includes a HindIII restriction site. The Δ13 mutant resulted from the sequential deletion of miR-BHRF1-1 and miR-BHRF1-3. ORF, open reading frame.

In addition to the BHRF1 miRNAs, the EBV genome also encodes 22 additional pre-miRNAs that are located within the BamHI-A rightward transcript (BART) intronic regions (5, 14, 24, 36), a small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) (18), and the 2 Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNAs (EBERs) (20). However, recombinant viruses that lack these other noncoding RNAs display either wild-type or only mildly reduced transformation efficiencies (18, 29, 31).

Previous work on the BHRF1 miRNA cluster did not delineate the respective contributions of the three BHRF1 miRNAs to the phenotypic traits displayed by B cells infected with the recombinant virus that lacks all three miRNAs. Therefore, we constructed recombinant viruses that lack only one of the BHRF1 miRNAs and their appropriate revertants. We compared their phenotypic traits with those observed with the triple BHRF1 miRNA knockout or with wild-type controls. This research reveals that all three miR-BHRF1 miRNAs contribute to B-cell transformation by EBV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary cells and cell lines.

HEK293 cells are neuroendocrine cells obtained by the transformation of embryonic epithelial kidney cells with adenovirus (11, 30). The Raji cell line is an EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cell line (26). The Elijah-neg cell line is an EBV-negative subclone of the EBV-positive Elijah BL cell line (courtesy of A. Rickinson, Birmingham, United Kingdom). WI38 cells are primary human lung embryonic fibroblasts (16). All cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Biochrom). Hygromycin (Hyg) at 100 μg/ml was added to the medium for the stable selection of HEK293 lines carrying the wild-type and recombinant viral genomes.

Plasmids and shuttle vectors.

The given coordinates correspond to EBV strain B95.8 (GenBank accession number V_01555.2). All PCR primers used for cloning are listed in Table 1. The targeting vector for the miR-BHRF1-1 mutant was generated by overlapping PCR cloning (see Table 1 for primer sequences). The resulting 1.8-kb PCR fragment includes a mutated miR-BHRF1-1 seed region (positions 52807 to 54651) and was cloned into a plasmid (B269) that consists of an arabinose-inducible temperature-sensitive bacterial origin of replication, the ampicillin (Amp) resistance gene, RecA, and the LacZ operon to generate a shuttle vector (B396) for chromosomal building. The following EBV fragments were cloned into B269 to construct shuttle vectors for the generation of revertant clones: a 1.1-kb Eco81I fragment (positions 53018 to 54169) for Δ1Rev (B404), a 2.9-kb BspTI/SalI fragment (positions 53222 to 56081) for Δ13Rev, and a 1.7-kb BglII/SalI fragment (positions 54359 to 56081) for Δ2Rev and Δ3Rev (B405).

Table 1.

Cloning primers used for generation of BHRF1 miRNA mutantsa

| Mutant | Oligonucleotide | Sequence | B95.8 positionsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Δ1 | fwd | GGTCTCTAGACTTCTTTTATCCTCTTTTTGG | 52807–52827 |

| rev | GCATCTAGAGTGAAATATCTCTAAAAATAC | 54631–54651 | |

| fwd.overlap | TATTAACGTTGCAAGCCCCGGAGTTGCCTGTTT | 53759–53791 | |

| rev.overlap | CGGGGCTTGCAACGTTAATAAGGAGCCGTCCTT | 53746–53778 | |

| Δ2 | fwd | CTTTTAAATTCTGTTGCAGCAGATAGCTGATACCCAATGTAACAGCTATGACCATGATTACGCC | 55136–55175 |

| rev | ATCCCACCTAGGACACCCAATTGTAGATATGGCCAGCACTCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAACGAC | 55199–55238 | |

| Δ3 | fwd | CAATTGGGTGTCCTAGGTGGGATATACGCCTGTGGTGTTCAACAGCTATGACCATGATTACGCC | 55216–55255 |

| rev | ATTTTAACGAAGAGCGTGAAGCACCGCTTGCAAATTACGTCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAACGAC | 55279–55318 |

EBV-specific sequences are underlined; mutated nucleotides are shown in boldface type. fwd, forward; rev, reverse.

GenBank accession number V_01555.2.

Expression plasmids spanning different parts of the BHRF1 gene region were cloned into the EcoRV site of pcDNA3.1(+); the wt plasmid spans the complete BHRF1 gene region with BHRF1 and the three BHRF1 miRNAs (positions 53222 to 56085), and plasmid B carries the BHRF1 gene only (positions 53805 to 55089). The B-2 plasmid carries BHRF1 and miR-BHRF1-2 (positions 53805 to 55216), B-3 includes BHRF1 and miR-BHRF1-3 (positions 53805 to 55089 and 55217 to 55563), plasmid B-2-3 includes BHRF1 and miR-BHRF1-2 and -3 (positions 53805 to 55563), and plasmid 1-B-2-3 includes BHRF1 and the three BHRF1 miRNAs (positions 53805 to 55089). A BspTI/ApaI fragment from the Δ2 mutant bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) that spans the mutated BHRF1 locus was cloned into the BspTI/ApaI site of pcDNA3.1(+) (positions 53222 to 55567).

Construction of BHRF1 miRNA recombinant viruses.

Wild-type EBV strain B95.8 cloned onto a prokaryotic F-plasmid, which carries the chloramphenicol (Cam) resistance gene, the gene for green fluorescent protein (GFP), and the Hyg resistance gene (p2089) (7), was used to generate the BHRF1 miRNA mutant clones. We constructed the miR-BHRF1-1 knockout virus (Δ1) by exchanging the seed region of this microRNA for an unrelated sequence in Escherichia coli by chromosomal building using B396 as a targeting vector, as described previously (9). The sequence of the mutant thus generated displays an additional AclI restriction site; digestion with this enzyme allows distinction between the mutant and the wild-type sequences (Fig. 1 and 2). The deletion of miR-BHRF1-2 or miR-BHRF1-3 was obtained by exchanging the viral DNA fragment that contains miR-BHRF1-2 (positions 55176 to 55197) or miR-BHRF1-3 (positions 55256 to 55278) for the kanamycin resistance gene flanked by Flp recombination sites, as described previously (9, 22). The kanamycin resistance cassette was amplified by using the primers listed in Table 1. After successful recombination the kanamycin cassette was excised by the transient transformation of the Flp recombinase cloned onto a temperature-sensitive plasmid (pCP20) to obtain the mutants Δ2 and Δ3 (Fig. 1 and 2). To generate virus producer cell lines, the Δ1, Δ2, and Δ3 recombinant viruses, which all contain a hygromycin resistance gene, were then transfected into HEK293 cells and submitted to hygromycin selection. Clones that showed good virus titers after lytic induction were selected and then evaluated by restriction enzyme analysis (Fig. 2) combined with sequencing to confirm both the integrity of the viral genomes and the exactitude of the introduced alterations. The three mutant genomes were used for the construction of revertant viruses in which the modified sequences were reexchanged with the original ones to reconstitute Δ1, Δ2, and Δ3 revertant virus genomes (22). Producer cell lines carrying the revertant genomes were then generated by using the hygromycin selection procedure described above for the mutants. The perfect identity of these revertants with wild-type sequences was confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis (Fig. 2) and sequencing.

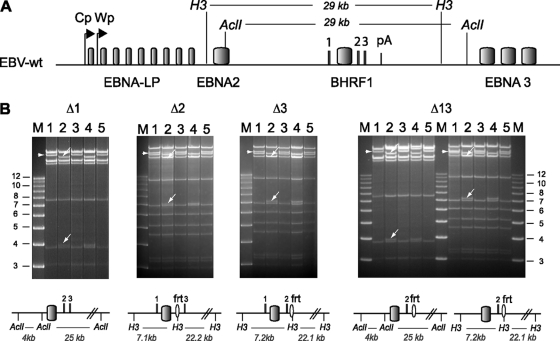

Fig. 2.

Restriction enzyme analysis of the BHRF1 miRNA single and double mutants. (A) Schematic overview of part of the EBV wt genome. Restriction enzyme recognition sites around BHRF1 and the size of the resulting restriction fragments are given. (B) For each recombinant virus, we analyzed the E. coli wt (lane 1), mutant (lane 2), and revertant (lane 3) BAC DNAs. Also included are the mutant (lane 4) and revertant (lane 5) EBV BACs isolated from the producer cell lines. The schematic inserted below each panel indicates the size of the predicted restriction fragments after successful mutagenesis, while the wild-type restriction profile is given in panel A. The resulting fragment changes observed after restriction analysis are indicated with arrows. H3, HindIII; M, molecular size marker (in kbp); frt, flip recombinase recognition site.

Subsequently, by use of the miR-BHRF1-1 mutant BAC, a double mutant lacking miR-BHRF1-1 and miR-BHRF1-3 (Δ13) was obtained by exchanging the viral DNA fragment that contains miR-BHRF1-3 for the kanamycin cassette, followed by the excision of the kanamycin cassette as described above and as reported previously (9). Revertant clones from all mutants were constructed by chromosomal building using the shuttle vectors described above. The construction of the triple mutant and its revertant was previously reported (10).

Cell transfections.

HEK293 cells were transfected with different expression plasmids that encode one or several BHRF1 miRNAs (0.5 μg/well of a 6-well plate) and pEGFP-C1 (0.2 μg/well) by lipofection (Metafectene; Biontex). The medium was changed the following day, cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and miRNAs were extracted as described below. The transfection efficiency was calculated by counting the number of GFP-positive cells in each well.

Stable clone selection and plasmid rescue into E. coli.

Recombinant EBV plasmids were transfected into HEK293 cells by lipofection and selected for hygromycin resistance (100 μg/ml). Recombinant EBV genomes were purified from GFP-positive hygromycin-resistant cell clones as described previously (12) and electroporated into E. coli DH10B cells as described previously (22).

Virus induction and titer quantification.

All described producer cell line clones were lytically induced by the transfection of a BZLF1 expression plasmid together with a BALF4 expression plasmid (23). The medium was changed the next day, and virus supernatants were harvested 3 days later, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and stored at −80°C. Viral genome equivalents were determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using EBV BALF5-specific primers and probe as described previously (8). Infectious titers were determined by infecting 105 Raji B cells with increasing 5-fold dilutions of supernatants. Three days after infection, the percentage of GFP-positive cells was assessed by using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Uninfected Raji cells were used as a negative control.

Infection of primary B lymphocytes.

Primary B cells were freshly isolated from adult human blood buffy coats by density gradient centrifugation, followed by positive selection using CD19 Dynabeads (Invitrogen). B cells were exposed to supernatants at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 infectious particles per B cell overnight at 37°C and then seeded at a concentration of 102 cells per well in 96-U-well plates coated with irradiated WI38 feeder cells. The number of wells with proliferating cells was determined at 6 weeks postinfection (p.i.). Infection experiments were also carried out at a high B-cell concentration; 2 × 106 B cells were exposed to infectious supernatant at an MOI of 0.1 infectious particles per cell and were harvested for RNA and protein extraction at different time points p.i.

Stem-loop real-time PCR.

RNAs were extracted from lymphoblastoid cell clones or transfected HEK293 cells by using an miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). One hundred ten nanograms of total RNA was reverse transcribed by using specific stem-loop primers and a TaqMan miRNA reverse transcription (RT) kit (Applied Biosystems) as described elsewhere previously (6, 25). qPCRs were performed as described previously (10). In brief, 110 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed by use of a mix of BHRF1 miRNA stem-loop primers in one RT reaction mixture. qPCR mixtures (20-μl volume) for each BHRF1 miRNA contained 1.5 μM forward primer, 0.7 μM reverse primer, 0.2 μM probe, and 1× TaqMan Universal Master Mix. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15s and 56°C for 1 min. Reverse transcription and amplification of cellular snoRNA RNU48 were performed in parallel to normalize for cDNA recovery (catalog no. 001006; Applied Biosystems) as recommended by the manufacturer. qPCR was performed on an ABI 7300 real-time detection system (Applied Biosystems).

Real-time PCR of latent EBV genes.

Four hundred nanograms of RNA isolated from infected B cells was reverse transcribed with avian myoblastosis virus (AMV) RT (Roche), using a mix of cDNA primers specific for Cp- and Wp-initiated transcripts, BHRF1 transcripts, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), as reported previously (4, 19). qPCR using primers specific for Cp- and Wp-initiated transcripts was performed as described previously (4). Latent BHRF1 transcripts were detected by using a forward primer in the Y2 exon as reported previously (19). qPCR and data analysis were carried out by using the universal thermal cycling protocol with an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR system. All samples were run in duplicates, together with primers for the amplification of the human GAPDH gene in combination with a VIC-labeled probe (Applied Biosystems) to normalize for variations in cDNA recovery.

Western blot analysis.

The preparation of cell extracts, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and Western blotting were performed as previously described (10). The following antibodies were used: EBNA-LP (JF186), actin (ACTN05; Dianova), and goat-anti-mouse antibody coupled with horseradish peroxidase as a secondary antibody (Promega). Antibody binding was revealed by use of an ECL detection reagent (Perkin-Elmer). Densitometric analyses of specific Western blot signals were performed by using ImageJ software.

RESULTS

All three BHRF1 miRNAs contribute to EBV-mediated B-cell transformation.

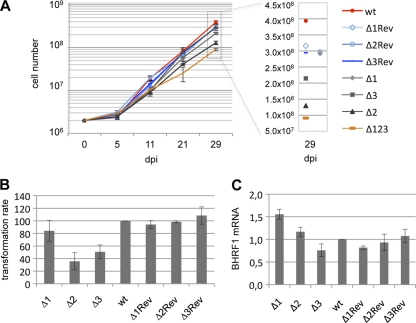

We started our investigations by performing B-cell transformation assays at high or at low B-cell concentrations with the mutants that lack one of the BHRF1 miRNAs; these viruses are described in the legends of Fig. 1 and 2. The first condition allowed the establishment of lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) derived from a large number of B cells and therefore avoided clonal effects. The second condition was more stringent but allowed a precise evaluation of the transforming potential of each viral mutant. Therefore, we exposed 2 × 106 primary resting B cells isolated from several peripheral blood samples to Δ1, Δ2, and Δ3 viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 infectious particles per B cell and monitored cell growth over a period of 4 weeks (Fig. 3A). Under these conditions, B cells infected with these defective viruses resumed growth and established continuously growing cell lines. We concluded that the loss of any single BHRF1 miRNA did not result in the ablation of the transforming properties of EBV. However, the growth kinetics were different among the different infected populations (Fig. 3A); the deletion of miR-BHRF1-1 had no effect on B-cell growth compared to that of wild-type controls. In contrast, only 30% and 50% of cell numbers could be obtained after infection with the Δ2 and Δ3 viruses, respectively. Interestingly, LCLs generated with either of these single BHRF1 miRNAs mutants grew more rapidly than the LCLs obtained by infection with the Δ123 triple mutant (Fig. 3A). This implies that the deletion of any one BHRF1 miRNA did not abrogate the transforming functions of the two remaining miRNAs. Infection experiments performed at low B-cell concentrations (102 cells/well) from multiple blood samples confirmed and refined the above-described results; all three BHRF1 miRNAs were found to contribute to EBV-mediated transformation (Fig. 3B). Based on three transformation assays, the Δ1 virus exhibited on average a 20% reduction in the transformation efficiency relative to that of wild-type controls, whereas B-cell transformation rates with the Δ2 and Δ3 viruses were 35% and 50% of those observed with the controls, respectively.

Fig. 3.

B cells transformed by the different single BHRF1 miRNA mutants display defective cell growth relative to that of their wild-type counterparts but evince normal BHRF1 expression levels. (A) Growth curve of EBV-infected B cells in the first weeks postinfection. Mean total cell numbers from three independent B-cell infection experiments are shown. Positive controls included LCLs generated with wild-type or revertant viruses. An LCL that carries Δ123 was also included in the panel as a reference. For clarity, the mean cell number measured at 29 days postinfection (dpi) is presented on the right at a higher resolution. (B) Cell transformation assays were carried out at a low B-cell concentration (102 cells/well) with an MOI of 0.1 infectious particles per B cell. The transformation rate is the ratio between the number of wells exhibiting B-cell outgrowth and the total number of seeded wells. Results are presented relative to the values obtained with the LCL generated with wt EBV. Averages of the results of three independent infection experiments are presented. (C) BHRF1 mRNA expression at day 30 postinfection in three unrelated primary B-cell samples infected with Δ1, Δ2, Δ3, their revertants, or wt EBV viruses. Results are presented relative to the values obtained with the LCL generated with wt EBV. The mean values from three independent analyses are given.

The BHRF1 protein was previously implicated in EBV-mediated B-cell transformation (19). BHRF1-specific transcripts can be initiated either from the Cp/Wp promoter in EBV-transformed cells or from a promoter located immediately 5′ of miR-BHRF1-1 in cells undergoing lytic replication (2). We examined latent BHRF1-specific transcription using a qPCR-based assay in which the 5′ primer binds to Wp; it therefore identifies latent BHRF1 mRNA transcripts and not the EBNA introns from which the miRNAs are produced (19). We found that latent BHRF1 expression was conserved in all tested samples, although there was some variation among them (Fig. 3C). However, this heterogeneity was also observed among the four different positive controls. We conclude that the effects of the BHRF1 miRNAs on B-cell growth are unlikely to result from alterations in BHRF1 global transcription.

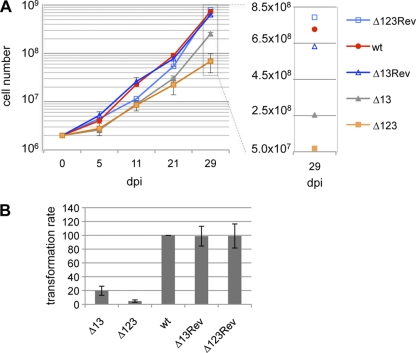

We next extracted RNA from the various LCLs thus obtained and assessed their BHRF1 miRNA expression patterns with the help of a specific RT-qPCR assay. This analysis, reported in Fig. 4, revealed that LCLs transformed with the Δ1 virus express miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3 at levels comparable to or even slightly higher than those of wild-type controls in the case of miR-BHRF1-3. MiR-BHRF1-1 expression was completely negative, as expected. LCLs that carried Δ3 viruses also displayed the expected pattern; i.e., transformed B cells expressed solely miR-BHRF1-1 and miR-BHRF1-2 at levels that were slightly increased relative to those of the wild-type controls. However, analyses of B-cell lines that carry the Δ2 virus yielded unexpected results. Indeed, LCLs generated with the Δ2 virus evinced a 25 to 30% reduction in miR-BHRF1-1 expression levels compared to those of the wild-type controls and those of its revertant. However, it is important that other wild-type revertants expressed miR-BHRF1-1 at levels only marginally higher than those in the LCL that carries this defective virus. The picture was clearer with miR-BHRF1-3, whose expression level was only 13% to 16% relative to that of the wild type or revertant controls, suggesting that miR-BHRF1-2 is required for the full expression of miR-BHRF1-3. This opened the enticing prospect of a so-far-uncharacterized mechanism of regulation of miRNA expression. However, it also questioned the validity of Δ2 viruses to specifically delineate miR-BHRF1-2 functions. Indeed, it was unclear whether the reduced miR-BHRF1-3 expression level would have an impact on the functions exerted by this miRNA during B-cell transformation. We therefore constructed a double-knockout virus that lacked miR-BHRF1-1 and miR-BHRF1-3 (Δ13). We reasoned that a comparison of the Δ13 and Δ123 transforming abilities would directly address the contribution of miR-BHRF1-2 to this process. We therefore repeated the above-described experiments with this double mutant. At high B-cell concentrations, B cells transformed with Δ13 grew more slowly than B cells from the same donors exposed to the wild-type viruses (Fig. 5A). However, the growth rate of B cells exposed to this double mutant remained higher than that of a B-cell line generated from the same B cells exposed to the Δ123 virus. Transformation assays performed with low B-cell numbers from the same donors and single, double, and triple BHRF1 miRNA mutants gave an overview of the contribution of the BHRF1 miRNAs to B-cell transformation (Fig. 3B and 5B). Indeed, monitoring of B-cells transformed with the Δ13 virus revealed that this mutant exhibits an enhanced transformation efficiency (20% relative to that of the wt) compared to that of Δ123 (5% relative to that of the wt), thereby confirming that miR-BHRF1-2 plays a substantial role during EBV-mediated transformation. The expression of miR-BHRF1-2 at wt levels in the Δ13 LCLs was confirmed by stem-loop RT-qPCR (Fig. 4). Taken together, we found that the single BHRF1 miRNA mutants were more transforming than the double mutant that was itself more transforming than the triple mutant.

Fig. 4.

miR-BHRF1-2 is necessary for full miR-BHRF1-3 expression. We determined the BHRF1 miRNA expression profile from three LCL sets generated with Δ1, Δ2, Δ3, Δ13, Δ123, and their wild-type counterparts by stem-loop RT-qPCR using primers specific for miR-BHRF1-1, miR-BHRF1-2, and miR-BHRF1-3. Data were normalized to RNU48 expression levels and are expressed relative to the value observed for one wt LCL, which was set to 1. EBV-negative Elijah cells were used as a negative control.

Fig. 5.

B cells transformed by viruses expressing only miR-BHRF1-2 display defective cell growth relative to that of their wild-type counterparts. A B-cell transformation assay with Δ13 viruses was performed at high (A) or low (B) B-cell concentrations under the same conditions as those described in the legends of Fig. 3A and B. Controls included Δ123 and the wild-type counterparts.

miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3 modulate EBNA transcription initiated from both the Cp and Wp promoters.

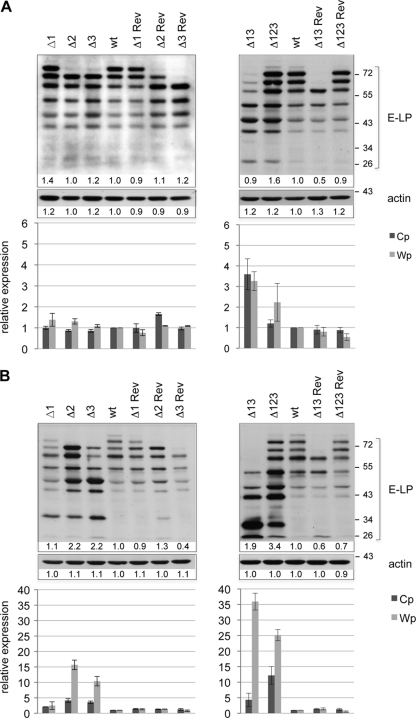

The other defining phenotypic trait displayed by the Δ123 miRNA knockout was enhanced latent gene transcription (10). While in B cells infected with the wild-type virus, levels of Wp-initiated EBNA transcripts were maximal 5 days after infection and decreased rapidly thereafter, they persisted at high levels in B cells from the same donors infected with the Δ123 virus. Similarly, Cp-driven EBNA transcription was markedly stronger in B cells transformed with Δ123 than in control LCLs (10). We therefore gauged the transcriptional activity from these 2 promoters in cell lines generated with our panel of defective viruses or with wild-type and revertant viruses. These experiments, illustrated in Fig. 6, evidenced enhanced transcription from both the Cp and Wp promoters in all LCLs generated with defective viruses except Δ1. This process became obvious at day 36 postinfection (Fig. 6B, bottom) but was already visible to some extent after 11 days (Fig. 6A, bottom). However, EBNA transcription levels were proportional to the number of deleted BHRF1 miRNAs; B cells infected with the Δ2 or Δ3 virus exhibited lower transcription levels than those infected with the double or the triple deletion mutants (Fig. 6B, compare bottom left and right panels). B cells infected with Δ123 produced more Cp-derived transcripts than did those exposed to Δ13. The opposite picture emerged for Wp-initiated transcripts, which remained more abundant in B cells transformed by Δ13 than in those infected with Δ123. This upregulated transcription resulted in an increased protein expression level, as indicated by the results of a Western blot analysis performed with a monoclonal antibody specific to EBNA-LP (Fig. 6A and B, top panels). EBNA-LP is a latent protein whose expression was most profoundly altered in B cells transformed with the Δ123 virus (10). Although the level of expression of this protein typically declines a few days after the onset of transformation, as can be seen for the controls, B cells infected with the Δ2, Δ3, Δ13, or Δ123 virus retained high levels of EBNA-LP production even at 36 days postinfection (Fig. 6B, top panels).

Fig. 6.

Latent promoter usage and EBNA-LP synthesis in transformed B cells. EBNA-LP expression in B cells transformed with mutant and control viruses at day 11 (A) and day 36 (B) postinfection was determined by Western blot analysis (top panels). The intensity of the Western blot signals was measured by using ImageJ software. Results are given below each sample as a ratio of the intensity compared to that of the corresponding wt band, which was set as 1. RT-qPCR was performed to assess Cp- and Wp-initiated EBNA transcript levels at day 11 (A) or day 36 (B) postinfection (bottom panels). Analyses of the single mutant and corresponding revertant viruses are depicted in the left panel, and the double (Δ13) and triple (Δ123) mutants and the corresponding revertants are shown in the right panel. RT-qPCR results obtained at a given time point are given relative to those for wt EBV at the same time point and represent mean values obtained from three independent infection experiments.

miR-BHRF1-2 is required for full miR-BHRF1-3 expression.

We then wished to investigate the downregulation of miR-BHRF1-3 in the Δ2 mutant in more detail. We first attempted to reproduce these results with an expression plasmid that exactly reproduces the gene organization present in this virus. With this aim, the viral DNA fragment that encompasses the complete BHRF1 locus in the Δ2 virus was cloned onto a eukaryotic expression plasmid. The corresponding wild-type sequence was also cloned to provide a positive control, and both plasmids were transfected into HEK293 cells. We then assessed BHRF1 miRNA expression levels in these cells using stem-loop RT-qPCR; we found that, as expected, miR-BHRF1-2 was not expressed and that the expression levels of miR-BHRF1-3 and, to a certain extent, of miR-BHRF1-1 were reduced relative to wild-type levels (Fig. 7A), reflecting the situation seen with the Δ2 mutant virus. We conclude that the expression pattern observed for the complete virus depends only on the genetic elements present in the BHRF1 locus. Furthermore, as this locus has been completely sequenced, we can be confident that the miRNA expression pattern seen for B cells infected with Δ2 is not the result of unwanted mutations in the recombinant virus. We then sought to directly demonstrate that miR-BHRF1-2 enhances the expression of miR-BHRF1-3. With this aim, we compared the expression levels of miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3 from plasmids that carry only one of these genetic elements or both miRNAs together on one plasmid. To ensure that the flip recombinase target (Frt) site that was introduced onto the recombinant plasmid had no influence on miRNA processing, we excluded this bacterial DNA sequence from this series of plasmids. The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 7B. We found that the expression of miR-BHRF1-2 was not influenced by the presence (B-2 plus B-3) or absence (B-2) of miR-BHRF1-3. In contrast, the expression level of miR-BHRF1-3 in the absence of miR-BHRF1-2 (B-3) was about 10-fold lower than wild-type levels (1-B-2-3), but the cotransfection of miR-BHRF1-2 had no enhancing effect (B-2 plus B-3). The expression of miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3 from the same plasmid (B-2-3), however, gave rise to a 25-fold increase in the expression level compared to that with a plasmid that expresses miR-BHRF1-3 only, clearly demonstrating that the enhancing effect of miR-BHRF1-2 on miR-BHRF1-3 requires both miRNAs to be present on the same transcript. The expression of miR-BHRF1-2 was marginally enhanced after the transfection of B-2-3 that carries miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3. We also noted that the transfection of a plasmid that contains all three BHRF1 miRNAs (1-B-2-3) gave rise to lower expression levels than those with plasmids that contain only one or two miRNAs. This effect was already observed to a certain extent for LCLs exposed to Δ3, in which the levels of both remaining miRNAs were slightly increased, or in LCLs generated with Δ1, which were found to produce slightly more miR-BHRF1-3 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 7.

miR-BHRF1-2 stimulates expression of miR-BHRF1-3 if both microRNAs are located on the same transcript. (A) The BHRF1 locus was cloned from a wt EBV BAC or from a Δ2 BAC onto an expression plasmid and was transfected into HEK293 cells to assess miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3 expression by stem-loop RT-qPCR. Shown are means of data from three independent transfection experiments, and results are given relative to values obtained with one experiment with the wt. (B) Expression plasmids that carry the BHRF1 open reading frame (B) and miR-BHRF1-2 (B-2), miR-BHRF1-3 (B-3), or both miRNAs (B-2-3) were transfected into 293 cells alone or in combination (B2 + B3). The expression levels of both BHRF1 miRNAs are given as mean values from two independent transfection experiments relative to values obtained with one wt plasmid comprising the complete BHRF1 miRNA locus (1-B-2-3).

DISCUSSION

Using EBV genomes that lack only one member of the BHRF1 miRNA cluster, we find that all three of these noncoding RNAs contribute to the transforming properties of EBV. How much these three miRNAs contribute to transformation appears more difficult to quantify precisely. MiR-BHRF1-1 seems to play only a limited role, since LCLs generated with the Δ1 virus grow at nearly the same rate as that of LCLs generated with wild-type viruses at high B-cell concentrations and retain 80% of the wild-type transformation potential at low B-cell concentrations. Experiments conducted with Δ3 viruses revealed that the deletion of this miRNA reduces transformation by roughly 50% and therefore appears to contribute more substantially to B-cell growth than miR-BHRF1-1. The results of the transformation assays conducted with Δ2 are more difficult to interpret, as this mutant not only is defective for miR-BHRF1-2 but also displays reduced miR-BHRF1-3 and possibly reduced miR-BHRF1-1 expression levels. Therefore, B cells infected with the Δ13 recombinant that expressed only miR-BHRF1-2 are more suitable for evaluations of the effect of this viral miRNA on B-cell transformation. We found that this mutant retained a transformation rate of 20% relative to that of wild-type viruses at low B-cell concentrations and compares to a transformation rate of 5% when all three miRNAs are deleted.

We also investigated latent gene expression in LCLs generated with the various mutants and found that miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3, but not miR-BHRF1-1, are required to keep EBNA transcription at wild-type levels. However, B cells infected with Δ13 exhibited higher transcription levels than those of B cells infected with Δ3; we infer that the latent gene expression level parallels the B-cell growth defects induced by the ablation of the BHRF1 miRNAs. However, it remains unclear whether enhanced EBNA expression is a cause or a consequence of impaired cell growth.

It was important to ensure that the abnormally low miR-BHRF1-3 expression level in B cells infected with Δ2 was not attributable to an adventitious mutation introduced into the virus mutant during its construction. This was unlikely, as we sequenced the BHRF1 locus in this mutant. Furthermore, we constructed a revertant of Δ2 that displayed a normal BHRF1 miRNA expression pattern and a normal transformation efficiency. Nevertheless, we wished to confirm these observations with another experimental system. With this aim, we subcloned the genomic locus that carries the BHRF1 gene, wild-type miR-BHRF1-1 and -3, as well as the miR-BHRF1-2 deletion from the Δ2 virus onto an expression plasmid. The transfection of this plasmid into HEK293 cells approximately reproduced the expression pattern observed in the context of the complete Δ2 virus (compare Fig. 4 and 7A); while miR-BHRF1-1 was expressed at around 40% of wild-type levels, miR-BHRF1-3 was downregulated by 10-fold. This establishes that the potentiating effect of miR-BHRF1-2 on miR-BHRF1-3 requires only sequences present in the BHRF1 locus. We conclude that the reduced miR-BHRF1-3 expression level observed for LCLs generated with Δ2 compared to those of wild-type controls is a direct consequence of the deletion of miR-BHRF1-2. Furthermore, we found that miR-BHRF1-2 exerts regulatory cis effects on miR-BHRF1-3; indeed, the expression level of miR-BHRF1-3 remained unchanged after the cotransfection of miR-BHRF1-2 relative to levels observed with the transfection of miR-BHRF1-3 alone. It is important that the constructs used in the latter experiments were devoid of the Frt sequence that we introduced into the virus recombinant. We can therefore formally exclude that the influence of miR-BHRF1-2 on miR-BHRF1-3 expression is due to the introduction of a bacterial sequence. One potential explanation for this observation is that the first miRNA facilitates the processing of the second. BHRF1 pre-miRNAs are formed in latency III-infected cells from intronic sequences of the large primary EBNA transcripts initiated from the Cp/Wp promoter (1, 5, 33). Previous work performed with the EBV-positive Burkitt's cell lymphoma cell line Akata identified a 1.3-kb transcript generated from large transcripts that span the BHRF1 locus following Drosha cleavage 3′ of miR-BHRF1-1 and 5′ of miR-BHRF1-2, together with processed BHRF1 miRNAs (33). Interestingly, a longer transcript that would stem from the cleavage between miR-BHRF1-2 and -3 could not be detected (33). This suggests, but does not formally prove, that the processing of the BHRF1 miRNAs located in the BHRF1 3′UTR is sequential and is initiated at miR-BHRF1-2. However, the structural requirements for pre-miRNA processing by the Drosha/DCGR8 complex (15, 34, 35), e.g., the basal stem that defines the Drosha cleavage site 11 bp away from the single-stranded basal segment, the overall length of the pre-miRNA, and the terminal loop, should not be affected in either the Δ2 mutant or the miR-BHRF1-3 expression plasmid, although it remains formally possible that the mutational inactivation of miR-BHRF1-2 induces some form of conformational rearrangement in the primary miRNA precursor that impacts the structure and, hence, the processing of the miR-BHRF1-3 stem-loop. Nevertheless, in total, these data suggest that the control of miRNA processing within the cluster extends beyond presently known sequence requirements. It is important that the miR-BHRF1-1 expression level was also reduced relative to that of wild-type controls in the plasmid context, suggesting that miR-BHRF1-2 might also be involved in the control of miR-BHRF1-1 expression. Therefore, interactions between miRNAs could extend beyond the identified interactions between miR-BHRF1-2 and miR-BHRF1-3. However, it remains unclear whether this mechanism is also effective in the context of the complete virus. In the same vein, we noticed the possible existence of a mild increase in the miRNA expression level in LCLs generated with Δ3 relative to wild-type levels. This became more obvious when these genetic elements were placed onto expression vectors, and we conclude that complex cis-acting regulatory interactions take place within the miRNA cluster.

Up to 40% of all human miRNAs are found organized into clusters (13). However, information about the respective contributions of each member to the functions of these clusters remains limited. We canvassed the literature and found three examples of human bicistronic miRNA clusters in which mice deficient in the whole cluster or in only one of its members were engineered. Mice devoid of miR144/451 or of miR451 alone exhibited impaired late erythroblastic maturation, suggesting that miR144 plays a limited role, if any, in vivo (27). The deletion of miR133a-1 or of miR133a-2 had no visible impact on mice (21). However, the deletion of both genes led to lethal heart ventricular-septal defects. Another example is provided by mice in which miR143 and miR145 were deleted either singly or in combination (32). The double-knockout mice exhibited abnormalities of the smooth muscle layers of arteries, arterial hypotension, and a profoundly impaired response to vascular injury. Most of these phenotypic traits were found to the same extent in the miR145−/− mice but were considerably milder in the miR143−/− mice (32). These three examples show that in cellular miRNA clusters, one miRNA contributes most or even all the observable functions performed by these miRNAs. In contrast, the viral BHRF1 cluster provides a new model in which all three miRNAs contribute to EBV-mediated B-cell transformation.

Whether the synergistic effect of miRNA clustering that we describe here extends to other viral or cellular clusters remains to be seen. However, in the case of EBV, the clustering of the 3 BHRF1 miRNAs permits the synchronous and synergistic expression of 3 genetic elements that all stimulate B-cell growth. A precise measurement of miR-BHRF1 miRNA expression levels revealed that BHRF1 miRNAs are expressed at lower levels than those of some highly expressed cellular miRNAs for reasons that are not yet apparent (1, 25). However, the clustering of miRNAs that serve the same functions might help reach a threshold above which they can collectively contribute significantly to transformation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Rowe for providing the EBNA-LP antibody.

Research reported here was supported by DKFZ grants to H.-J.D. and by award number R01-AI067968 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to B.R.C. S.D.L. was supported by grant T32-AI007392 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amoroso R., et al. 2011. Quantitative studies of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNAs provide novel insights into their regulation. J. Virol. 85:996–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Austin P. J., Flemington E., Yandava C. N., Strominger J. L., Speck S. H. 1988. Complex transcription of the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI fragment H rightward open reading frame 1 (BHRF1) in latently and lytically infected B lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:3678–3682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartel D. P. 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116:281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bell A. I., et al. 2006. Analysis of Epstein-Barr virus latent gene expression in endemic Burkitt's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumour cells by using quantitative real-time PCR assays. J. Gen. Virol. 87:2885–2890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cai X., et al. 2006. Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and differentially expressed. PLoS Pathog. 2:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen C., et al. 2005. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delecluse H. J., Hilsendegen T., Pich D., Zeidler R., Hammerschmidt W. 1998. Propagation and recovery of intact, infectious Epstein-Barr virus from prokaryotic to human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:8245–8250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feederle R., Bannert H., Lips H., Muller-Lantzsch N., Delecluse H. J. 2009. The Epstein-Barr virus alkaline exonuclease BGLF5 serves pleiotropic functions in virus replication. J. Virol. 83:4952–4962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feederle R., Bartlett E. J., Delecluse H. J. 2010. Epstein-Barr virus genetics: talking about the BAC generation. Herpesviridae 1(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feederle R., et al. 2011. A viral microRNA cluster strongly potentiates the transforming properties of a human herpesvirus. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1001294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graham F. L., Smiley J., Russell W. C., Nairn R. 1977. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 36:59–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Griffin B. E., Bjorck E., Bjursell G., Lindahl T. 1981. Sequence complexity of circular Epstein-Bar virus DNA in transformed cells. J. Virol. 40:11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Griffiths-Jones S., Saini H. K., van Dongen S., Enright A. J. 2008. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D154–D158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grundhoff A., Sullivan C. S., Ganem D. 2006. A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA 12:733–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Han J., et al. 2006. Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell 125:887–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hayflick L. 1965. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 37:614–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hutchings I. A., et al. 2006. Methylation status of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) BamHI W latent cycle promoter and promoter activity: analysis with novel EBV-positive Burkitt and lymphoblastoid cell lines. J. Virol. 80:10700–10711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hutzinger R., et al. 2009. Expression and processing of a small nucleolar RNA from the Epstein-Barr virus genome. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kelly G. L., et al. 2009. An Epstein-Barr virus anti-apoptotic protein constitutively expressed in transformed cells and implicated in Burkitt lymphomagenesis: the Wp/BHRF1 link. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lerner M. R., Andrews N. C., Miller G., Steitz J. A. 1981. Two small RNAs encoded by Epstein-Barr virus and complexed with protein are precipitated by antibodies from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:805–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu N., et al. 2008. microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev. 22:3242–3254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neuhierl B., Delecluse H. J. 2005. Molecular genetics of DNA viruses: recombinant virus technology. Methods Mol. Biol. 292:353–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neuhierl B., Feederle R., Hammerschmidt W., Delecluse H. J. 2002. Glycoprotein gp110 of Epstein-Barr virus determines viral tropism and efficiency of infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:15036–15041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pfeffer S., et al. 2004. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science 304:734–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pratt Z. L., Kuzembayeva M., Sengupta S., Sugden B. 2009. The microRNAs of Epstein-Barr virus are expressed at dramatically differing levels among cell lines. Virology 386:387–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pulvertaft R. J. V. 1964. Cytology of Burkitt's lymphoma (African lymphoma). Lancet i:238–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rasmussen K. D., et al. 2010. The miR-144/451 locus is required for erythroid homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 207:1351–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rickinson A. B., Kieff E. 2007. Epstein-Barr virus, p. 2655–2700 In Knipe D. M., et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 29. Seto E., et al. 2010. Micro RNAs of Epstein-Barr virus promote cell cycle progression and prevent apoptosis of primary human B cells. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shaw G., Morse S., Ararat M., Graham F. L. 2002. Preferential transformation of human neuronal cells by human adenoviruses and the origin of HEK 293 cells. FASEB J. 16:869–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swaminathan S., Tomkinson B., Kieff E. 1991. Recombinant Epstein-Barr virus with small RNA (EBER) genes deleted transforms lymphocytes and replicates in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:1546–1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xin M., et al. 2009. MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes Dev. 23:2166–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xing L., Kieff E. 2007. Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1 micro- and stable RNAs during latency III and after induction of replication. J. Virol. 81:9967–9975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zeng Y., Cullen B. R. 2003. Sequence requirements for micro RNA processing and function in human cells. RNA 9:112–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zeng Y., Yi R., Cullen B. R. 2005. Recognition and cleavage of primary microRNA precursors by the nuclear processing enzyme Drosha. EMBO J. 24:138–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu J. Y., et al. 2009. Identification of novel Epstein-Barr virus microRNA genes from nasopharyngeal carcinomas. J. Virol. 83:3333–3341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]