Abstract

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) displays strong lymphotropism in vivo, but paradoxically, established B cell lines have largely been refractory to infection by soluble KSHV virions. Here we show that this block can be overcome by exposure to cell-associated virus. Doxycycline-inducible recombinant KSHV.219 (rKSHV.219)-harboring SLK (iSLK.219) cells were employed as KSHV donors. Cocultivation of lymphoid cell lines with reactivated iSLK.219 cells resulted in readily demonstrable viral entry into each cell line; similar observations were made in primary tonsillar B cell cultures. Moreover, infected lymphoid cells were able to outgrow upon puromycin selection, indicating development of persistent infection. Infected BJAB cells display signatures of latent infection, including classical latency-associated transcripts, a punctate pattern of LANA expression, and episomal maintenance of the KSHV genome. However, when lytically activated by various chemical stimuli, infected BJAB cells were able to produce only low levels of infectious virions. These data demonstrate that (i) cell-associated viruses can bypass viral entry blocks in most lymphoid cell lines, (ii) the determinants of cell-associated virus entry differ from those of soluble virion infection, and (iii) immortalized lymphoblastoid lines have partial postentry blocks to efficient lytic reactivation.

INTRODUCTION

Although Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) infects endothelial cells in KS tumors, it belongs phylogenetically to the lymphotropic subfamily of herpesviruses (40). Consistent with this, in the circulation KSHV is primarily found in B cells (2, 30). Moreover, KSHV infection is also strongly associated with two B cell-derived lymphoproliferative disorders, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) (9, 10) and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) (43). In PEL, all the clonally derived B cells of the tumor harbor episomal KSHV DNA. Most cells are latently infected, but lytic infection can be induced with a variety of chemicals (13, 27, 31, 38, 42). MCD is a more complex lesion histologically, but again in MCD-involved nodes KSHV infection is restricted to B cells. All these findings indicate that KSHV infection in vivo is profoundly lymphotropic.

In vitro, KSHV virions can infect a wide variety of cell lines, even those derived from cell types that are not naturally infected in vivo. Paradoxically, however, all established B cell lines tested to date have been refractory to infection by such stocks (5, 7, 37), a fact that has greatly retarded study of infection in the lymphoid compartment. There is good reason to believe that lymphatic infection by KSHV may have a number of properties not reproduced in nonlymphoid cells; for example, latently infected PEL cells display expression of vIRF3 (also called LANA2), a viral protein not expressed in latently infected KS specimens (39). Of course, lymphoid cells are the only cells in which effects of infection on B cell-specific processes such as B cell receptor (BCR) signaling or antigen presentation can be studied. However, the inability to infect B cell lines has made it difficult to address issues like these experimentally. Although many PEL cell lines exist (10, 25, 38), these are imperfect starting points for examination of the effects of KSHV on B cell biology, since for each such line no isogenic uninfected counterpart exists.

Although two systems now exist for infection of primary B cells in vitro, infection in these systems is inefficient, and infected primary B cells do not become immortalized and therefore cannot be substantially expanded (21, 32, 34, 35). Consequently, while there is much to be learned from such systems, they are not likely to be useful for detailed biochemical studies. Because of these limitations, we have reexamined the potential of established B cell lines to be infected by KSHV. We report here that although B cell lines are refractory to infection by cell-free virus, they can be infected by cocultivation with cell monolayers lytically infected with KSHV, and most infected lymphoma cell lines could establish stable KSHV-harboring clones. Furthermore, infected BJAB cells demonstrated characteristic features of latency. When properly induced, they produced viable viruses, although this process was inefficient and required more extensive chemical treatments. Thus, cell-mediated transmission mediates KSHV infection into otherwise resistant lymphoma cell lines. Such lines can now provide a reproducible system to examine selected aspects of the interactions of KSHV with lymphoid-specific functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, reagents, and plasmids.

SLK and Vero76 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% glutamate and penicillin-streptomycin. BJAB, Ramos, Jurkat, and SUP-T1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% glutamate and antibiotics. Hygromycin was purchased from Invitrogen, puromycin from Invivogen, and G418 from Sigma. QBI293A cells were purchased from QBiogene. Transwell permeable supports (0.4 μm) were purchased from Corning. CD13- and CD45-specific antibodies were purchased from BioLegend. Human CD45 microbeads were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec. RG108, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, was purchased from Sigma. pcDNA3-derived constructs expressing KSHV ORF50 (RTA) (28) and ORF57 (MTA) (24) were described elsewhere.

Cell-mediated transmission of rKSHV.219 by coculture.

Generation of inducible iSLK.219 cl.10 cells was as described elsewhere (33); these cells contain recombinant KSHV.219 (rKSHV.219) (45) and express RTA under control of a doxycycline (DOX)-responsive promoter (tetracycline-responsive element [TRE]). iSLK.219 cl.10 cells were left untreated or induced with 0.2 μg/ml DOX. At 48 h postinduction, lymphoma cells, including BCBL-1, JSC-1, BJAB, Ramos, Jurkat, and SUP-T1 cells, were added to the iSLK.219 cl.10 cell culture in the same compartment or the upper compartment, which allows two different cell types to be in direct contact or separated by a membrane, respectively. After 2 to 3 days of coculture, lymphoma cells were harvested and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. When indicated, lymphoma cells were purified using CD45 microbeads.

Flow cytometry.

Infected lymphoma cells were stained with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD13 antibody (specific to SLK cells) and phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody (specific to lymphoma cells). Infection of lymphoma cells by rKSHV.219 was examined by gating out CD13+ SLK cells and gating for green fluorescent protein-positive (GFP+) CD45+ lymphoma cells. Stained cells were subsequently washed once with incomplete phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min at room temperature (RT). With a subsequent wash in cold incomplete PBS, cells were resuspended in FACS staining buffer (4% FBS and 0.09% sodium azide). Titration of cell-free rKSHV.219 in the culture supernatant was performed as described previously (34). Cell marker-specific staining or GFP expression was examined on an LSR II instrument (BD Bioscience). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo software.

Cell sorting and selection of rKSHV-infected lymphoma cells.

To select rKSHV.219-infected lymphoma cells, cells were first sorted using human CD45 microbeads. The purity of the resulting cells reached over 98% (CD45+ CD13−). Isolated cells were cultured in the presence of puromycin at various concentrations until resistant cells outgrew and negative cells were completely eliminated: for BJAB cells at 0.4 μg/ml, for Ramos cells at 0.2 μg/ml, for Jurkat cells at 0.3 μg/ml, and for SUP-T1 cells at 1 μg/ml.

Generation of DOX-inducible BJAB cells containing rKSHV.219.

DOX-inducible BJAB cells, which express RTA under control of the TRE promoter, were generated as described below. BJAB cells were first transduced by retroviruses expressing rtTA, with subsequent selection with G418 (800 μg/ml). rtTA-expressing BJAB cells were subsequently transduced by retroviruses expressing RTA under control of the TRE. The resulting cells were selected with hygromycin B (200 μg/ml), and stable cells were termed iBJAB cells. iBJAB cells were infected with recombinant KSHV.219 viruses by coculturing with induced iSLK.219 cl.10 (cell-mediated transmission is described above). rKSHV.219-harboring iBJAB (iBJAB.219) cells were selected in the presence of puromycin (0.4 μg/ml).

Analysis of viral gene expression by tiling microarray analysis.

Tiling microarray analysis on the KSHV transcriptome was described previously (11). Briefly, total RNA from BJAB or BCBL-1 cells was extracted using RNA-Bee (Tel-Test, Inc.) and further purified using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Labeled cRNA was generated from 400 ng of total RNA using two-color Quick Amp labeling (Agilent) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Experimental samples (labeled with cyanine 5-CTP) and reference samples (labeled with cyanine 3-CTP) were competitively hybridized to custom viral microarrays (Agilent) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Washed and processed arrays were scanned using a GenePix 400B scanner (Axon Instruments), and a graphical presentation of processed data (heat map) was generated with Java Treeview.

Induction of lytic reactivation in infected B cell lymphoma cell lines.

iBJAB.219 cells were induced in the presence of DOX and/or valproate, sodium butyrate, or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA). Cells were induced for 2 to 3 days for the examination of red fluorescent protein (RFP) expression or for 5 days for virus production in the culture supernatant. BCBL-1 cells were induced by valproate (600 μM) for 2 to 3 days as indicated.

Confocal microscopy.

BJAB.219 cells were maintained before cytospin in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM glutamate, 400 μg/ml G418 (Sigma), 200 μg/ml hygromycin, and 1 μg/ml puromycin. One million cells were centrifuged at 1,300 rpm for 10 min on Histobond microscope slide (VWR) by employing a Cyto-Tek centrifuge (Sakura). Cells were washed twice in PBS, fixed in paraformaldehyde (PFA) (4% in PBS, 10 min), and then washed (twice in PBS) and permeabilized (10 min, in 0.1% sodium citrate and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS). And after two washes in PBS, cells were blocked in permeabilization buffer supplemented with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (blocking buffer) in PBS for 30 min. Unlabeled anti-LANA antibody (Advanced Biotechnologies) was labeled using the Alexa Fluor 647 monoclonal antibody labeling kit (Invitrogen) prior to cell staining, and 1 μg Alexa 647-conjugated anti-LANA antibody was diluted in blocking buffer, added to cells, and stored at 4°C for 60 min. After two washes in PBS, stained cells were covered with Vector Shield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories Inc.). The images presented in Fig. 2B were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy using a microscope system (EZ-C1Si; Nikon) equipped with a Plan-Apo 100×, 1.40-numerical-aperture (NA) oil objective and 405-, 488-, and 561-nm laser lines.

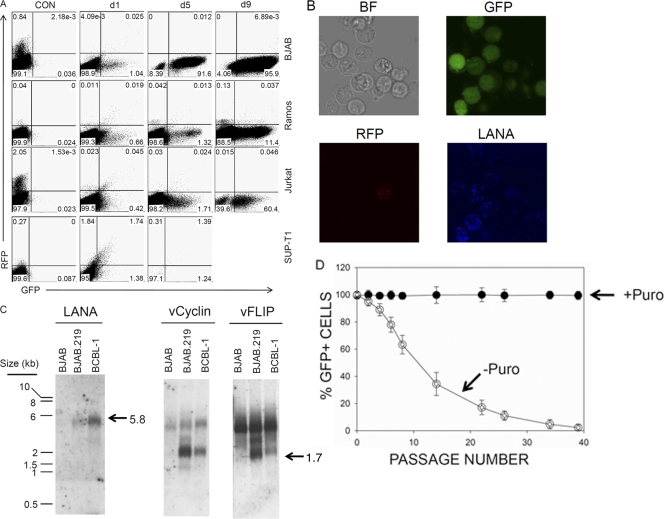

Fig. 2.

Stable rKSHV-infected lymphoma cells emerge upon puromycin selection and display key features of viral latency. (A) After being cocultured with induced iSLK.219 cl.10 cells, infected lymphoma cells were harvested and purified with human CD45 microbeads. Purified cells were selected in the presence of puromycin at various concentrations (see Materials and Methods). Emergence of puromycin-resistant rKSHV.219-infected lymphoma cells was monitored over time by flow cytometry on two channels: GFP (x axis) and RFP (y axis). (B) Infected BJAB cells (BJAB.219) were stained with Alexa Fluor 647-labeld anti-LANA antibody, and images were taken with a confocal microscope. (C) Total RNAs from BJAB, BJAB.219, and BCBL-1 cells were isolated, and mRNA was enriched. Two micrograms of mRNA was loaded and resolved on a 1% agarose gel (see Materials and Methods). Gene-specific probes were used to detect LANA, vCyclin, and vFLIP mRNAs. Size markers are shown on the left, and specific bands are indicated by an arrow with the estimated mRNA size. (D) BJAB.219 cells were cultured in the presence (1 μg/ml) (closed symbols) or absence (open symbols) of puromycin for the indicated number of passages. In each passage, 2 × 105 (/ml) cells were passed in fresh complete RPMI 1640 medium, and cells became confluent after 2 to 3 days (1 × 106 cells/ml). Cells were subjected to FACS analysis, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was examined.

Northern blot analysis of viral latent gene expression.

The detection of KSHV transcripts by Northern blotting has been published elsewhere (11). Total RNA was extracted from BJAB, BJAB.219, or BCBL-1 cells. mRNA was purified using the Oligotex mRNA midikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two micrograms of mRNA was loaded on a 1% agarose gel containing 1× MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) buffer and 37% formaldehyde. A biotin-11-UTP-labeled riboprobe was generated with T7 promoter-containing PCR products using the AmpliScribe T7-flash transcription kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For gene-specific riboprobes, the following primer sets were used: LANA forward primer, 5′-ATAATCTTGCACGGGTCGTC-3′; LANA reverse primer, 5′-AATTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGTTATGGGCGACTGGTCTG-3′; vCyclin forward primer, 5′-CGTTGGCCCTTAATCTTTTG-3′; vCyclin reverse primer, 5′-AATTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTATCCTGCGGAATGACGTT-3′; vFLIP forward primer, 5′-TTAAAGGAGGAGGGCAGGTT-3′; and vFLIP reverse primer, 5′-AATTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGGCGATAGTGTTGGGAGTGT-3′. Biotinylated riboprobes were hybridized to the membranes in Ultrahyb buffer at 68°C overnight. Bound biotinylated riboprobes were detected using BrightStar BioDetect (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Gardella gel analysis.

Cells were washed in cold incomplete PBS twice, resuspended in sample loading buffer (15% Ficoll, 40 μg/ml RNase A, and 0.01% bromophenol blue in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer), and subsequently loaded on a Gardella gel as previously described (18, 19) with minor modifications. Samples were loaded and run immediately at 40 V for 4 h and at 120 V for an additional 16 h. A KSHV-specific probe was prepared using the Rediprime II random prime labeling system (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions to incorporate [32P]CTP (Perkin-Elmer), with 25 ng purified BAC36 (48) used as the template. 32P-labled probes were hybridized to the membrane at 42°C overnight. The hybridized membrane was washed three times with low-stringency buffer (2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.5% SDS) at 42°C for 30 min and three times with high-stringency buffer (1× SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 62°C for 1 h for each wash. The membrane was exposed to a Kodak BioMax MS film.

Quantitative real-time PCR on viral gene expression.

The detailed experimental procedure was described elsewhere (34). Fifty nanograms of DNase I-treated of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using gene-specific primers for ORF50 (RTA), ORF59, and ORF22 (gH). Primers and probes were as follows: ORF50 forward primer, 5′-CACAAAAATGGCGCAAGATGA-3′; ORF50 reverse primer, 5′-TGGTAGAGTTGGGCCTTCAGTT-3′; ORF50 probe, 5′-FAM-TAGAGTTGGGCCTTCAGTT-MGB-3′; ORF59 forward primer, 5′-GTTTACCCCCGGGCTGAT-3′; ORF59 reverse primer, 5′-GGGCACACCTTCCACTTCTAAT-3′; ORF59 probe, 5′-FAM-TGGCACTCCAACGAA-MGB-3′; ORF22 forward primer, 5′-TGTGGCCGCCACACAA-3′; ORF22 reverse primer, 5′-GGGCAAACTGGCCAACTTC-3′; and ORF22 probe, 5′-FAM-TAGCTCGCGTGTCCG-MGB-3′. Reverse primers were used to generate gene-specific cDNA in reverse transcription reactions. Plasmids carrying each gene were used as standards.

Statistical analysis.

The data represented in this study are either representative or shown as the means ± standard deviations (SD) from 3 or 4 independent experiments. The statistical significance of differences in the mean values was evaluated with the 2-tailed Student t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Cell-associated but not cell-free virus can infect established lymphoid lines.

Since immortalized B cell lines cannot be infected with soluble KSHV virions (references 5, 7, and 37 and unpublished observations), we explored a different route of infection, using cell-associated rather than cell-free virus. For these studies, we employed rKSHV.219, which bears a constitutive GFP gene (and puromycin resistance locus) as well as an RFP gene under the control of a lytic promoter (45). This virus was used to infect SLK endothelial cells that had previously been engineered to express a doxycycline (DOX)-inducible RTA gene (33). RTA (replication and transcription activator) is the viral transcription factor whose expression governs the switch from latency to lytic replication in KSHV (27, 28, 44, 47). As such, this line (called iSLK.219) is latently infected in the absence of DOX but lytically infected in its presence. From this mass culture, a clone (cl.10) was identified (33), which had a very low basal level of RFP expression (<0.1%) but was strongly induced by DOX (>98% of cells were RFP+ by day 4 of DOX exposure). Supernatants from DOX-induced cultures of cl.10 had >107 infectious KSHV virions/ml, as judged by their ability to transduce naïve 293 cells to GFP positivity. Accordingly, iSLK.219 cl.10 was used as the donor of KSHV in all transmission experiments described below.

We examined 6 lymphoid cell lines for infectibility by rKSHV.219: BJAB and Ramos (KSHV-negative B cell lines), BCBL1 and JSC1 (KSHV-positive PEL lines), and Jurkat and SupT1 (T cell lines). Transmission from induced iSLK.219 cl.10 was examined in two contexts: (i) donor and recipient lines were cocultured at 1:1 ratios, and (ii) donor and recipients were plated in opposite wells of a Transwell dish (in this case, the lymphoid cells were exposed to virus-laden culture medium but could not make direct contact with SLK cells). To assay for transmission, lymphoid cells were removed from the dishes by aspiration (since they grow in suspension, while SLK cells are adherent) and examined for GFP expression by flow cytometry. To ensure that no contaminating SLK cells could be scored in this assay, we gated on CD45+ cells, since all lymphoid lines express this marker (CD45+ and CD13−), while SLK cells do not (CD45− and CD13+), and we quantitated the percentage of these cells that were GFP+. To our surprise, in a given culture, CD45+ CD13+ cells accounted for fewer than 0.2% by FACS analysis (Fig. 1). This suggests that a minimal number of cell fusion events occurred, and lymphoid and endothelial cells were easily distinguishable after coculture.

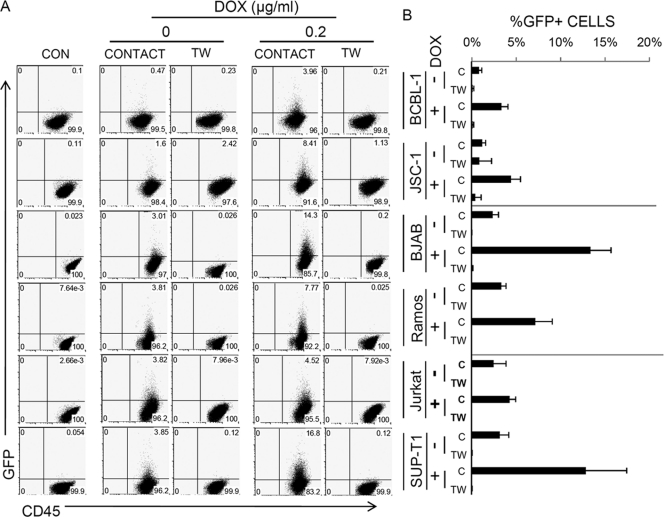

Fig. 1.

Lymphoma cells are efficiently infected by cell-mediated transmission. (A) iSLK.219 cl.10 cells, left uninduced or induced by 0.2 μg/ml for 2 days, and various lymphoma cells were cocultured in direct contact or separated by a Transwell membrane (TW). After 2 days of coculture, CD45-positive lymphoma cells were gated for their GFP expression. A representative FACS plot is shown. CON, control lymphoma cells without coculture. (B) Means and standard errors of the means (SEM) from 3 independent cell-mediated transmission experiments. C and TW, contact and Transwell, respectively.

Figure 1 shows that at baseline, all lymphocytes were GFP negative, and, in accord with previous studies (5, 7), none became GFP positive by exposure to culture medium from iSLK.219 cl.10 in Transwell dishes, even after strong induction of lytic replication in that cell line by exposure to DOX. However, after cocultivation in contact with DOX-induced iSLK.219 cl.10, every lymphoid line displayed CD45+ GFP+ cells, albeit with different efficiencies. BJAB B cells and SupT1 T cells were the most efficiently infected by cocultivation, with ∼15% of each population showing evidence of infection. Even PEL cells, which already harbor resident KSHV genomes, could be superinfected with rKSHV.219 at an efficiency of ∼5%. It is interesting to note that Vero cells, a fibroblast cell line derived from African green monkey, could transmit virus to BJAB and Ramos cells by direct cell-cell contact at different efficiencies (unpublished observations). Thus, cell-mediated transmission is effective even across species barriers. Interestingly, smaller numbers of cells in several lines became infected following contact with iSLK.219 cl.10 cells in the absence of DOX, although no resistant cells grew out in those cultures upon selection; as expected, such transfer was greatest in the most susceptible recipient lines (e.g., BJAB and SupT1).

Infected BJAB cells display many key features of latent infection.

Cell-cell transfer of KSHV resulted in 5 to 15% of cells being infected. To expand the available number of infected lymphoid cells, we sought to derive stable lines by selecting for the puromycin resistance marker carried by rKSHV.219 (45). Following cocultivation with induced iSLK.219 cl.10 cells, lymphoid suspension cells were harvested by aspiration and cell enrichment with microbeads coated with anti-CD45 antibody and were recultured in the presence of puromycin at various concentrations. In BJAB, Ramos, and Jurkat cells we successfully established stable puromycin-resistant lines (Fig. 2A). However, despite repeated attempts, we were unable to recover a stable puromycin-resistant line with SUP-T1 cells in this fashion. The failure to establish stable clones with SUP-T1 cells is most likely due to lytic replication in infected cells, as suggested by spontaneous RFP expression (Fig. 2A, bottom panels). On day 9 postselection, there were not enough numbers of live SUP-T1 cells for FACS analysis, and there were insufficient numbers of events at day 5 postselection as well. Other potential mechanisms are discussed below. Furthermore, the kinetics of stable line generation were different among infected lymphoid lines (Fig. 2A). Stable BJAB cells outgrew by 5 days after selection with puromycin. However, it took notably longer for the other cell lines to establish rKSHV.219-harboring stable cultures: roughly 3 weeks for Jurkat cells and 4 weeks for Ramos cells.

As KSHV establishes latent infection in most established cell lines in vitro (5; reviewed in reference 17), we characterized the viral latency program in infected BJAB B cells, which readily yielded puromycin-resistant cells after cocultivation (Fig. 2A). Figure 2B shows that the cells were GFP positive and also displayed abundant LANA expression by immunofluorescence, in the classical punctate nuclear pattern. Northern blotting for the mRNAs of the major latency locus revealed the presence of the classically described mRNAs for LANA, v-Cyc, and v-FLIP (Fig. 2C). This suggests that the cells were latently infected.

Latent infection by KSHV is often unstable, particularly after de novo infection in vitro (19). To see whether infected BJAB cultures share this property, we removed the selection for puromycin and followed the persistence of the viral genome, as judged by GFP expression. As shown in Fig. 2D, the cells rapidly became GFP negative, suggesting episome loss—exactly as authentic KSHV episomes behave following virion infection in adherent cell lines (19). Episomal maintenance of the KSHV genome in BJAB cells was further supported by Gardella gel analysis (18, 19) (unpublished observations). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that rKSHV.219 virus can establish latency in BJAB cells when transmitted by cell-cell contact.

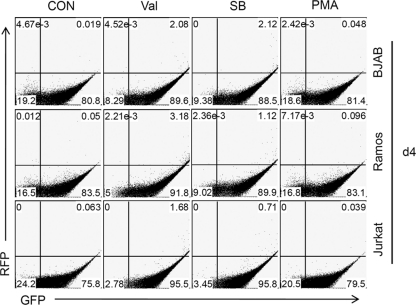

Infected lymphoma cells are poorly inducible by chemical stimuli.

As infected lymphoma cells display normal latency upon infection (Fig. 2), we next sought to rescue the virus from its latency by treating the cells with chemical inducers (31, 38, 42). Stably infected BJAB.219, Ramos.219, and Jurkat.219 cells were tested for their inducibility by valproate, sodium butyrate, or PMA (Fig. 3). On the basis of RFP expression, none of them seemed to robustly reactivate in the presence of inducing stimuli. Consistent with this interpretation, induced culture supernatants from all 3 lines at day 5 did not contain any GFP-transducing infectious viruses, as judged by titration on 293 cells (unpublished observations).

Fig. 3.

Reactivation of stable rKSHV.219-infected lymphoma cells in response to chemical stimuli. Established rKSHV.219-infected lymphoma cells were induced using valproate (600 μM) (Val), sodium butyrate (600 μM) (SB), or PMA (20 ng/ml). At day 4 postinduction, cells were subjected to flow cytometry to analyze lytic reactivation based on RFP expression (y axis). SUP-T1 cells were not included, as they failed to establish stable puromycin-resistant clones.

Generation of DOX-inducible RTA-expressing BJAB cells harboring rKSHV.219 (iBJAB.219 cells) and viral reactivation in response to inducing stimuli.

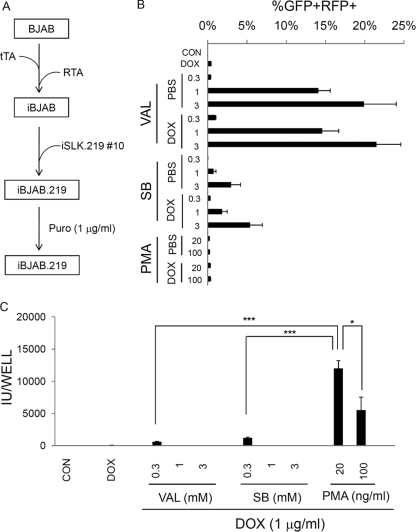

As lymphoma cells display very low levels of reactivation based on RFP expression and little, if any, viable virus production in response to inducing stimuli (Fig. 3 and unpublished observations), we hypothesized that the failure of infected lymphoma cells to reactivate may be attributed to low levels of expression of RTA, the lytic switch protein of KSHV (27, 28, 44, 47). RTA binds to the promoters of many delayed-early genes (e.g., those for polyadenylated nuclear transcript [PAN], kaposin, thymidine kinase, ORF57, K8/RAP, K2, K9, and K14) in a sequence-specific manner and to one late gene (that for gB) (reviewed by Deng et al. [16]), upregulating their expression. Thus, it is plausible that ectopic expression of RTA in a controlled manner may avoid cell toxicity due to RTA overexpression, ensuring lytic replication of KSHV. To test this possibility, we generated an iBJAB.219 cell line (Fig. 4A), in which an RTA transgene is inducible by DOX. Although DOX alone proved to be an inefficient inducer of these cells (as judged by RFP expression), addition of valproate or sodium butyrate led to much more efficient induction of RFP expression in these cultures. However, these histone deacetylase complex (HDAc) inhibitors resulted in the release of only trace quantities of infectious KSHV from these BJAB cells, as judged by the ability of the medium to transduce naïve 293 cells to GFP positivity (Fig. 4C). Surprisingly, PMA treatment, which induced minimal levels of RFP expression (Fig. 4B), reproducibly induced more viable GFP-transducing viruses than the HDAc inhibitors (Fig. 5C). This implies that PAN promoter-driven RFP expression may not provide an accurate assessment of full viral replication in lymphoid cell lines. We have noticed a similar discrepancy in primary tonsillar cells (34) as well as in iSLK.219 cells under certain experimental conditions (reference 33 and unpublished observations). We do not know the basis of this phenomenon.

Fig. 4.

Generation of DOX-inducible RTA-expressing rKSHV.219-infected BJAB (iBJAB.219) cells and their reactivation in response to various stimuli. (A) iBJAB.219 cells were generated as described in Materials and Methods. (B) iBJAB.219 cells were left uninduced or induced for 3 days with DOX (1 μg/ml) and/or various chemicals at different concentrations as indicated. Subsequently, cells were subjected to flow cytometry, and GFP+ RFP+ cells were scored. One representative plot out of 3 independent experiments is shown. Results for duplicate samples were averaged, and means were plotted with standard deviations. Val and SB, valproate (VAL) (mM) and sodium butyrate (SB) (mM), respectively. PMA was used at 20 or 100 ng/ml. (C) At day 5 postinduction, culture supernatants from induced cells (B) were titrated on 293 cells (see Materials and Methods). Mean infectious units (IU) for duplicate samples were plotted. CON, PBS control group. Means and SEM from 4 independent experiments are shown. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

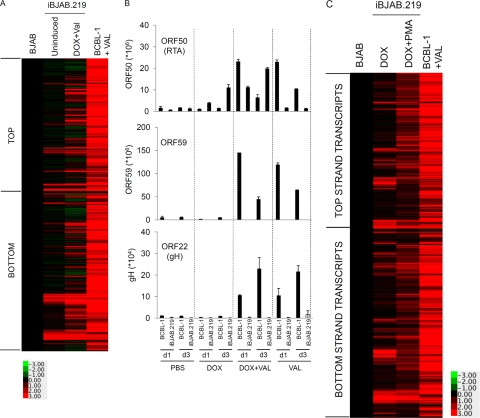

Fig. 5.

Viral gene expression profiling in iBJAB.219 cells. (A) Total RNA was extracted from BJAB cells, iBJAB.219 cells (uninduced or induced [1 μg/ml DOX and 600 μM valproate]), and BCBL-1 cells (induced with 600 μM valproate). Cells were induced for 3 days. Four hundred nanograms total RNA was used for labeling and hybridized to a custom KSHV genomic tiling microarray (see Materials and Methods). KSHV tiling microarray data (ordered by genome position) are displayed for 13,444 unique probes. The color bar indicates the fold change relative to the level for BJAB cells. VAL, valproate. TOP and BOTTOM, top- and bottom-strand transcripts of the KSHV genome, respectively. Data for one representative experiment out of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on ORF50, ORF59, and ORF22 to validate the microarray data. Plasmids carrying each gene were used as positive controls and standards to enumerate the number of mRNA copies per 200 ng total RNA used. Each experimental group is indicated by dotted lines for comparison between groups. (C) iBJAB.219 cells were induced with DOX alone or with DOX and PMA, and total RNA was extracted. Custom KSHV array analysis was performed as for panel A to profile viral gene expression. For comparison, BCBL-1 cells induced for 3 days with valproate (600 μM) were included. The color bar indicates the fold change relative to the level for BJAB cells. Data for one representative experiment 2 independent experiments are shown.

Of note, the levels of viable viruses from iBJAB.219 cells (induced by DOX plus PMA) are ∼1,000-fold below those produced by induced iSLK.219 cl.10 cells (∼ 107 infectious units [IU]/ml) (33). These data suggest that there is a partial postentry block(s) to KSHV reactivation, as previously suggested by others for BJAB cells, in which studies viral entry was bypassed by transfection of BAC36 or its derivatives (14, 15).

Viral gene expression is defective in iBJAB.219 cells treated with DOX and valproate.

The seemingly normal latency but scant production of infectious virus from iBJAB.219 cells led us to postulate that viral gene expression by HDAc inhibitors may be abnormal or defective in those cells although they are able to upregulate expression of RFP in response to HDAc inhibitors. To characterize the extent of viral gene transcription in iBJAB.219 cells, we undertook expression profiling on a custom KSHV tiling array (11) (Fig. 5A). As expected, this revealed a restricted pattern of viral gene expression in uninduced cells, although the extent of viral gene transcription in such cells is greater than observed in latently infected SLK.219 cells (reference 11 and unpublished observations). In addition to the major latency locus, iBJAB.219 cells also express detectable transcripts emanating from LANA2/vIRF3 as well as ORF9, -10, and -11, an antisense transcript of LANA, and transcripts from repeated regions (Fig. 5A and Table 1). More importantly, induced iBJAB.219 cells (Fig. 5A, lane 3) displayed much less extensive transcription than induced PEL cells such as BCBL-1 cells (lane 4). Although over 20 lytic genes were being transcribed at appropriate levels in induced iBJAB.219 cells (Table 1), many other essential lytic functions were unexpressed or poorly expressed in these cells, including many key regulatory genes and much of the machinery of viral DNA replication (Table 1). Selected abnormalities of viral lytic gene expression in iBJAB.219 cells induced by DOX and valproate were confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR for 3 viral lytic genes (Fig. 5B): ORF50, ORF59, and ORF22. In contrast, when induction was by DOX and PMA, the gene expression profile of iBJAB.219 cells was much more extensive than that induced by DOX and valproate (Fig. 5C), albeit at lower levels than that of induced BCBL-1 cells. This observation partly explains why iBJAB.219 cells produce detectable viable viruses when induced by DOX and PMA but not when induced by valproate. In addition, it is interesting to note that valproate seems to counteract PMA-mediated reactivation of KSHV from its latency (Fig. 6) (see below). Further investigation is required to delineate the basis of this phenomenon.

Table 1.

Viral lytic gene expression in induced lymphoma cell lines

| Expression level compared to that in uninduced cellsa | Genesb |

|---|---|

| Higher/comparable | K2, ORF2, K3, K4, K4.1, K4.2, K5, ORF23, ORF24, ORF39, ORF65, antisense LANA, ORF9, ORF10, ORF11, PAN, ORF16, ORF18, ORF27, ORF33, K8, K8.1, ORF37, vGPCR |

| Lower/little | RTA (IE), ORF45 (IE), antisense ORF29 (IE), ORF57 (DE), ORF21 (DE), DNA synthesis machinery (DE) |

Gene expression was categorized based on probe intensity (iBJAB.219 versus BCBL-1) obtained from microarray data (Fig. 5A). Note that the classification is arbitrary, based on the overall fold difference of the probe intensity.

IE and DE, immediate-early and delayed-early gene, respectively.

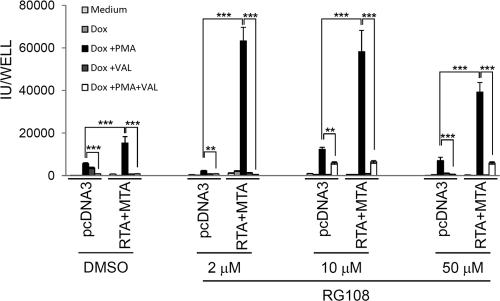

Fig. 6.

Partial remedy of viral production from iBJAB.219 cells by chemical treatment. iBJAB.219 cells were cultured in the presence of RG108 at different concentrations for 35 days before transfection with RTA plus MTA. At 20 h posttransfection, cells were treated with various chemicals as indicated for 5 days. Induced culture supernatants were titrated on QBI293A cells. Data from one representative experiment out of 3 independent experiments are shown. Values are means and standard deviations for duplicates. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Partial remediation of the defects of iBJAB.219 by inducers of demethylation of DNA and by ectopic expression of RTA and MTA.

The poor expression of RFP observed in chemically induced BJAB.219 cells (Fig. 3) suggested the possibility that defects in expression of key regulators (such as RTA and/or MTA), which control expression of many downstream genes, might account for some of the impairment of virus production in iBJAB.219 cells. We also considered the possibility that defective epigenetic regulation might make an additional contribution to the poor permissivity of BJAB cells to lytic growth, as the inducibility of iBJAB.219 cells seemed to decrease over time based on RFP expression in response to various inducing stimuli (unpublished observations). To explore these possibilities, we cultured iBJAB.219 cells for up to 35 days in the presence or absence of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor RG108 (8), which is efficient in demethylation and not toxic to cells, and then examined their ability to produce viable viruses either before or after transfection with expression vectors for RTA and MTA. RG108-treated cells did not show any signs of toxicity or growth retardation (reference 8 and unpublished observations). As shown in Fig. 6, RG108 and/or RTA and MTA coexpression by itself had very little effect on lytic induction; however, when cells were treated with PMA in conjunction with RG108 treatment and RTA/MTA coexpression, lytic reactivation was enhanced up to 10-fold compared to that with PMA alone. When these factors were optimized, yields of up to 60,000 to 80,000 infectious units/ml could be achieved.

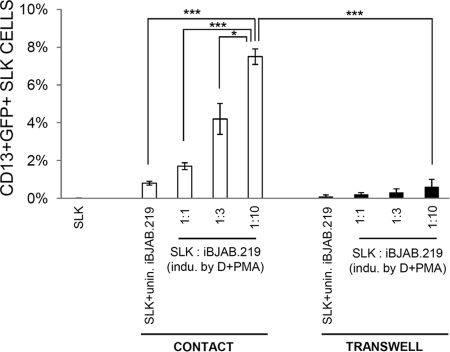

Induced iBJAB.219 cells transmit KSHV to uninfected SLK cells by cell-mediated transmission.

Although virus release from iBJAB.219 cells is lower (Fig. 4 and 6) than that from iSLK.219 cells, it is possible that induced iBJAB.219 cells may still be able to transmit KSHV by cell-associated transmission. To test for this possibility, iBJAB.219 cells were cultured with SLK cells either in direct contact or separated by a 0.4-μm membrane (Fig. 7). Induced iBJAB.219 cells were added to uninfected SLK cells at various ratios to ensure that the SLK cell culture monolayer was fully covered by iBJAB.219 cells (at ratios of 1:3 and 1:10). As expected, when separated by a membrane, induced iBJAB.219 cells could not efficiently transmit viruses to SLK cells (Fig. 7, right). In contrast, when induced BJAB.219 cells were cocultivated with SLK cells, up to 6 to 8% of the SLK cells became GFP positive. Furthermore, SLK cells infected in this manner could be selected in the presence of 1 μg/ml puromycin (unpublished observations), suggesting that stable latency was achieved. In addition, it is not likely that efficient cell-mediated transmission of KSHV from iBJAB.219 cells to SLK cells occurred by cell-cell fusion, as there were few, if any, cells doubly positive for CD13 (an endothelial marker) and CD45 (a leukocyte marker) in all experiments (<0.2% [data not shown]).

Fig. 7.

iBJAB.219 cells, when properly induced, are capable of transmitting viral progeny to uninfected SLK cells only through direct cell-cell contact. Uninfected SLK cells were cultured with iBJAB.219 cells in direct contact (CONTACT) or separated by a 0.4-μm membrane (TRANSWELL). Prior to coculture, iBJAB.219 cells were either left uninduced or induced by doxycycline (D) (1 μg/ml) and PMA (20 ng/ml) for 2 days. Uninduced iBJAB.219 cells were added at a 1:3 ratio and induced iBJAB.219 cells were added at various ratios to 5 × 104 SLK cells in a 24-well plate as indicated. After 3 days of coculture in the presence of DOX and PMA, SLK cells were washed twice with warm incomplete PBS and trypsinized for staining with anti-CD13-APC and anti-CD45-PE-Cy7. Stained cells were subjected to FACS analysis. CD45+ lymphoma cells were gated out with CD13+ SLK cells analyzed for GFP expression. unin., uninduced; indu., induced. Means and SEM from 3 independent experiments are shown. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

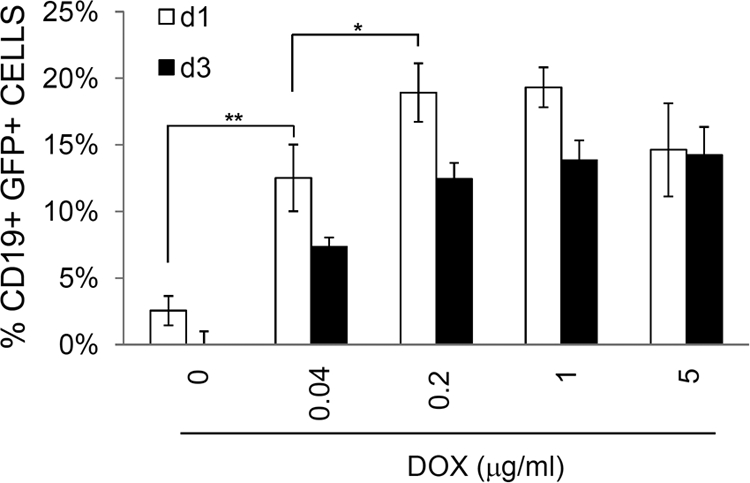

Tonsillar B cells are efficiently infected by cell-mediated transmission.

To explore the possibility that cell-mediated transmission can be utilized for infection of primary B cells, iSLK.219 cl.10 cells were induced by DOX and cocultured with tonsillar B cells for the indicated duration of infection. The results of a representative infection study are shown in Fig. 8. When cocultured with iSLK.219 cells induced by 0.2 μg/ml DOX, as many as 20% of the tonsillar B cells became GFP+. This level of infection was seen in cell-free virus infection only when the MOI was over 100 (unpublished observations). Therefore, these data imply that cell-mediated transmission is much more effective than cell-free virus infection.

Fig. 8.

Efficient infection of primary tonsillar B cells by cell-mediated transmission. Tonsillar B cells were purified and cocultured with iSLK.219 cells previously induced in the presence of DOX at various concentrations as indicated. At day 1 or 3, B cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometry for their expression of GFP (CD19+ GFP+). Means for duplicate samples were plotted with standard deviations. One representative plot out of 4 independent experiments is shown. Means and SEM for triplicates is shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

A longstanding paradox in the field of KSHV research has been that established B cell lines are resistant to infection with soluble KSHV virions, despite the known lymphotropism of the virus in vivo (5, 7, 37; reviewed in reference 17). In this report, we clearly demonstrate that cell-mediated transmission renders otherwise resistant B (and T) cell lymphoma cell lines susceptible to KSHV infection.

The inability of BJAB cells to support KSHV entry may be due, at least in part, to their lack of cell surface heparin sulfate, which is known to promote herpesvirus adsorption (1, 6). When a plasmid encoding functions for heparin sulfate was transfected into BJAB cells (23), the cell-free virus could bind to BJAB cells without apparent infection. Furthermore, our work and that of others indicate that BJAB cells have additional postentry blocks to KSHV lytic growth. Chen and Lagunoff (14, 15) bypassed de novo infection by transfection of the KSHV genome and demonstrated that BJAB cells can support viral postentry maintenance of a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-based KSHV genome (BAC36). Although BAC36-BJAB cells maintained BAC36 as an episome and displayed latent gene expression comparable to that of BCBL-1 cells when examined by Northern blotting, the authors were unable to detect lytic replication. Similarly, when we established infection of BJAB cells (and other lines) by cell-cell spread of KSHV, we also observed a profound (but not absolute) block to lytic reactivation in these lines. This block resides at least in part at the RNA level, since expression profiling (Fig. 5A and Table 1) reveals multiple defects in lytic RNA accumulation, which can be partly restored by PMA treatment (Fig. 4, 5C, and 6). DNA methylation may play an adjunctive role in this restriction of gene expression, since prolonged cultivation with a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor sensitizes BJAB cells to reactivation by the combination of PMA and ectopic expression of RTA and MTA (Fig. 7 and unpublished observations). Nonetheless, these yields still represent <1% of the yields of virus from induced iSLK.219 cells. Therefore, viral reactivation in infected BJAB cells seems to be more restricted than that in BCBL-1 cells and endothelial cells (Fig. 5 and unpublished observations), and this restriction is likely due to partial blocks at multiple steps in reactivation.

Our work builds on an earlier observation of Sakurada et al. (41), who demonstrated that cell-mediated transmission can efficiently mediate infection in adherent cell lines (e.g., endothelial cells) that are also susceptible to cell-free virions. Our work establishes for the first time that even cells that lack the canonical entry pathways mediating uptake of cell-free virions can be successfully infected by cell-cell spread. This indicates that the molecular determinants of viral entry by cell-cell spread must differ from those that mediate infection by soluble virions. The molecular identity of the determinants of cell-cell spread is presently unknown and constitutes an important subject for future investigation.

One criticism of cocultivation experiments might be that cell-cell fusion, rather than bona fide virus infection, might be responsible for the appearance of GFP+ CD45+ cells in the culture, as exemplified by some cellular processes and Sendai virus-induced cell fusion (3, 36; reviewed in reference 12). However, we believe that this is not the case in our experiments. If cell fusion takes place and is the main reason for emergence of GFP+ lymphoma cells, then most GFP+ lymphoma cells are expected to be doubly positive for CD45 (a lymphoid marker) and CD13 (an SLK marker). However, CD45+ CD13+ lymphoid cells were fewer than 0.2% of the infected population in all the experiments carried out. Furthermore, if cell fusion were the sole mechanism of cell-cell transfer of virus, the resulting syncytia would not be expected to grow out efficiently as stable cell lines, and such lines should display obvious heterokaryon formation, which we did not observe among stable lines generated in this way. We conclude that cell-cell fusion has little involvement in the cell-associated virus spread described here.

Cell-mediated transmission was also highly effective in primary tonsillar B cell infection by KSHV (Fig. 8). Up to 20% of tonsillar cells expressed GFP after 1 day of culture in direct cell-cell contact with iSLK.219 cl.10 cells, which were induced prior to coculture. This level of infection was detectable with cell-free viruses only at MOIs of over 100 infectious units (unpublished observations). These results indicate that cell-associated viruses are much more effective in infecting not only established lymphoma cell lines but also primary B cells. It is known that dendritic cell (DC) association with HIV facilitates viral transmission to naïve uninfected T cells. An accumulating body of evidence shows that virological synapses are established between DC-T cell junctions (22, 29), which allows efficient HIV transmission (20, 46). Viral proteins seem to be involved in the process of polarization for synapse formation (4, 26). However, there is little evidence to date that DCs play a similar role in KSHV infection, and it remains to be determined whether cell-cell spread of KSHV proceeds via the formation of virological synapses similar to those in HIV transmission.

Finally, although the low permissivity of lymphoblastoid cell lines for lytic KSHV infection limits their experimental utility (e.g., as virus producer lines), the ability to infect such lines should provide useful reagents for the study of lymphoid cell-specific signaling and its regulation by latent KSHV infection. In addition, the ability to infect lymphoid lines by cell-cell spread provides an experimental system in which identification of the receptor(s) required for this form of entry can be approached.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant R01 CA096491-05 from the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akula S. M., Wang F. Z., Vieira J., Chandran B. 2001. Human herpesvirus 8 interaction with target cells involves heparan sulfate. Virology 282:245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ambroziak J. A., et al. 1995. Herpes-like sequences in HIV-infected and uninfected Kaposi's sarcoma patients. Science 268:582–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aroeti B., Henis Y. I. 1991. Accumulation of Sendai virus glycoproteins in cell-cell contact regions and its role in cell fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15845–15849 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnard A. L., Igakura T., Tanaka Y., Taylor G. P., Bangham C. R. 2005. Engagement of specific T-cell surface molecules regulates cytoskeletal polarization in HTLV-1-infected lymphocytes. Blood 106:988–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bechtel J. T., Liang Y., Hvidding J., Ganem D. 2003. Host range of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured cells. J. Virol. 77:6474–6481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Birkmann A., et al. 2001. Cell surface heparan sulfate is a receptor for human herpesvirus 8 and interacts with envelope glycoprotein K8.1. J. Virol. 75:11583–11593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blackbourn D. J., et al. 2000. The restricted cellular host range of human herpesvirus 8. AIDS 14:1123–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brueckner B., et al. 2005. Epigenetic reactivation of tumor suppressor genes by a novel small-molecule inhibitor of human DNA methyltransferases. Cancer Res. 65:6305–6311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cesarman E., Chang Y., Moore P. S., Said J. W., Knowles D. M. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1186–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cesarman E., et al. 1995. In vitro establishment and characterization of two AIDS-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood 86:2708–2714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chandriani S., Xu Y., Ganem D. 2010. The lytic transcriptome of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus reveals extensive transcription of noncoding regions, including regions antisense to important genes. J. Virol. 84:7934–7942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen E. H., Olson E. N. 2005. Unveiling the mechanisms of cell-cell fusion. Science 308:369–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen J., et al. 2001. Activation of latent Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by demethylation of the promoter of the lytic transactivator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:4119–4124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen L., Lagunoff M. 2005. Establishment and maintenance of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency in B cells. J. Virol. 79:14383–14391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen L., Lagunoff M. 2007. The KSHV viral interleukin-6 is not essential for latency or lytic replication in BJAB cells. Virology 359:425–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deng H., Liang Y., Sun R. 2007. Regulation of KSHV lytic gene expression. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 312:157–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ganem D. 2006. KSHV infection and the pathogenesis of Kaposi's sarcoma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 1:273–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gardella T., Medveczky P., Sairenji T., Mulder C. 1984. Detection of circular and linear herpesvirus DNA molecules in mammalian cells by gel electrophoresis. J. Virol. 50:248–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grundhoff A., Ganem D. 2004. Inefficient establishment of KSHV latency suggests an additional role for continued lytic replication in Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 113:124–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gummuluru S., KewalRamani V. N., Emerman M. 2002. Dendritic cell-mediated viral transfer to T cells is required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 persistence in the face of rapid cell turnover. J. Virol. 76:10692–10701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hassman L. M., Ellison T. J., Kedes D. H. 2011. KSHV infects a subset of human tonsillar B cells, driving proliferation and plasmablast differentiation. J. Clin. Invest. 121:752–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Igakura T., et al. 2003. Spread of HTLV-I between lymphocytes by virus-induced polarization of the cytoskeleton. Science 299:1713–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jarousse N., Chandran B., Coscoy L. 2008. Lack of heparan sulfate expression in B-cell lines: implications for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infections. J. Virol. 82:12591–12597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirshner J. R., Lukac D. M., Chang J., Ganem D. 2000. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus open reading frame 57 encodes a posttranscriptional regulator with multiple distinct activities. J. Virol. 74:3586–3597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Komanduri K. V., Luce J. A., McGrath M. S., Herndier B. G., Ng V. L. 1996. The natural history and molecular heterogeneity of HIV-associated primary malignant lymphomatous effusions. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 13:215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Llewellyn G. N., Hogue I. B., Grover J. R., Ono A. 2010. Nucleocapsid promotes localization of HIV-1 gag to uropods that participate in virological synapses between T cells. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lukac D. M., Kirshner J. R., Ganem D. 1999. Transcriptional activation by the product of open reading frame 50 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for lytic viral reactivation in B cells. J. Virol. 73:9348–9361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lukac D. M., Renne R., Kirshner J. R., Ganem D. 1998. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection from latency by expression of the ORF 50 transactivator, a homolog of the EBV R protein. Virology 252:304–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McDonald D., et al. 2003. Recruitment of HIV and its receptors to dendritic cell-T cell junctions. Science 300:1295–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mesri E. A., et al. 1996. Human herpesvirus-8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a new transmissible virus that infects B cells. J. Exp. Med. 183:2385–2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller G., et al. 1997. Selective switch between latency and lytic replication of Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus and Epstein-Barr virus in dually infected body cavity lymphoma cells. J. Virol. 71:314–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Myoung J., Ganem D. 2011. Active lytic infection of human primary tonsillar B cells by KSHV and its noncytolytic control by activated CD4+ T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 121:1130–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Myoung J., Ganem D. 2011. Generation of a doxycycline-inducible KSHV producer cell line of endothelial origin: maintenance of tight latency with efficient reactivation upon induction. J. Virol. Methods 174:12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Myoung J., Ganem D. 2011. Infection of primary human tonsillar lymphoid cells by KSHV reveals frequent but abortive infection of T cells. Virology 413:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rappocciolo G., et al. 2008. Human herpesvirus 8 infects and replicates in primary cultures of activated B lymphocytes through DC-SIGN. J. Virol. 82:4793–4806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rawling J., Garcia-Barreno B., Melero J. A. 2008. Insertion of the two cleavage sites of the respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein in Sendai virus fusion protein leads to enhanced cell-cell fusion and a decreased dependency on the HN attachment protein for activity. J. Virol. 82:5986–5998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Renne R., Blackbourn D., Whitby D., Levy J., Ganem D. 1998. Limited transmission of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured cells. J. Virol. 72:5182–5188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Renne R., et al. 1996. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat. Med. 2:342–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rivas C., Thlick A. E., Parravicini C., Moore P. S., Chang Y. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA2 is a B-cell-specific latent viral protein that inhibits p53. J. Virol. 75:429–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Russo J. J., et al. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:14862–14867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sakurada S., et al. 2001. Effective human herpesvirus 8 infection of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by cell-mediated transmission. J. Virol. 75:7717–7722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shaw R. N., Arbiser J. L., Offermann M. K. 2000. Valproic acid induces human herpesvirus 8 lytic gene expression in BCBL-1 cells. AIDS 14:899–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Soulier J., et al. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood 86:1276–1280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun R., et al. 1998. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:10866–10871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vieira J., O'Hearn P. M. 2004. Use of the red fluorescent protein as a marker of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression. Virology 325:225–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang J. H., Kwas C., Wu L. 2009. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), but not ICAM-2 and -3, is important for dendritic cell-mediated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission. J. Virol. 83:4195–4204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu Y., et al. 2005. A Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 ORF50 deletion mutant is defective for reactivation of latent virus and DNA replication. J. Virol. 79:3479–3487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou F. C., et al. 2002. Efficient infection by a recombinant Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cloned in a bacterial artificial chromosome: application for genetic analysis. J. Virol. 76:6185–6196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]