Abstract

Despite high heritability, a large fraction of cases with schizophrenia do not have a family history of the disease (sporadic cases). Here, we examine the possibility that rare de novo protein-altering mutations contribute to the genetic component of schizophrenia by sequencing the exome of 53 sporadic cases, 22 unaffected controls and their parents. We identified 40 de novo mutations in 27 patients affecting 40 genes including a potentially disruptive mutation in DGCR2, a gene removed by the recurrent schizophrenia-predisposing 22q11.2 microdeletion. Comparison to rare inherited variants revealed that the identified de novo mutations show a large excess of nonsynonymous changes in cases, as well as a greater potential to affect protein structure and function. Our analysis reveals a major role of de novo mutations in schizophrenia and also a large mutational target, which together provide a plausible explanation for the high global incidence and persistence of the disease.

Schizophrenia (SCZ) has a strong genetic component1,2. Despite the high heritability, a large fraction of SCZ cases do not have a family history of the disease (sporadic cases)3. Although largely ignored in earlier efforts to model disease risk, de novo germline mutations may account for a significant fraction of sporadic SCZ cases. In agreement with this hypothesis, rare de novo copy number variants (CNVs)4 are emerging as an important genomic cause of psychiatric disease and the variant with strongest statistical support for association with SCZ, namely the 22q11.2 microdeletion, is a de novo and recurrent mutation5,6.

Availability of next-generation whole genome or exome sequencing7 now permits the study of de novo mutations [point substitutions (or single nucleotide variants, SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (in/dels)] in a systematic genome-wide manner8,9. Pilot studies in patients with SCZ focusing on specific synaptic genes identified a small number of putative de novo mutations 10. However, the full contribution of rare de novo SNVs and in/dels to SCZ remains unknown. In this study, we use family-based whole-exome sequencing to test the hypothesis that de novo protein-altering mutations contribute substantially to the genetic component of SCZ.

We sequenced the exomes of 53 family trios of subjects diagnosed with SCZ or schizoaffective (SCZAFF) disorder, with no history of the disease in a first- or second-degree relative (‘sporadic cases cohort’) as well as family trios from 22 unrelated healthy controls, all recruited from the European descent genetically homogeneous Afrikaner population in South Africa11,12. Presence or absence of family history in cases was not a screening criterion during recruitment but could be reliably determined because of the close-knit family structure of the families and the availability of detailed psychiatric records over several generations due to the large catchment area and long-term care provided by the local recruiting hospital6,12,13. Control families completed a detailed self-report questionnaire that inquired about several psychiatric conditions, including phobias, anxiety, depression and history of treatment for any of these conditions. Also, mental illness in first- or second-degree relatives was excluded. Based on previous results6,13 we excluded carriers of rare de novo CNVs. Identities were coded and analysis was performed blind to affected status while maintaining knowledge of the parent-child relations. From all 225 individuals we extracted DNA samples from whole blood.

We enriched exonic sequences using the Agilent SureSelect technology for targeted exon capture and performed Illumina paired-end sequencing (one lane of flow-cell per sample, see Methods). On average, we obtained 7.3 Gb of mappable sequence data per individual after exome enrichment, targeting 37 Mb from exons and their flanking regions. Overall, we covered 1.22% of the genome, a fraction corresponding to the NCBI Consensus Coding Sequences database (CCDS). The paired-end reads were cross-matched to the reference genome (hg19 build) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA v0.5.81536)14. 97.9% of the reads were properly aligned to the reference genome. Our median read depth is 65.2X, which is higher than the estimated average depth (33X) required for highly accurate downstream heterozygous variant detection. In addition, 92.4% of the captured target exons were covered by high quality genotype calls at least 8 times to ensure good detection sensitivity15 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of exome sequencing data production

| Average | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sequence (bp) | 7,475,900,117 | 100.00% |

| Aligned Sequence (bp) | 7,319,357,510 | 98.34% |

| Aligned Paired reads | 69,747,339 | 97.55% |

| Aligned Singleton reads | 566,300 | 0.35% |

| Median Read Depth | 65.2 X | |

| 1x Coverage | 37,191,631 | 98.84% |

| 4x Coverage | 36,190,388 | 96.18% |

| 8x Coverage | 34,769,095 | 92.40% |

| 20x Coverage | 30,428,158 | 80.87% |

| 30x Coverage | 27,171,231 | 72.21% |

Our de novo mutation detection pipeline is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1. We implemented a series of filters, including final validation by standard Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Figure 2 and 3), to eliminate variants that would appear de novo either from under-calling in the parents or systematic false positive calls in the subjects (see Methods). In total, in the affected trios we observed 34 de novo point mutations (33 SNVs and 1 dinucleotide substitution) and 4 de novo in/del candidates (Table 2). Overall, 27 out of 53 patients (~51%) carry at least one de novo mutational event. This rate is comparable to the one reported for 20 parent-child trios with autism spectrum disorders (51%)8, but somewhat lower compared to the one reported for 10 parent-child trios with intellectual disability (90%)9. Ten of the 27 patients carried more than one de novo mutation and the rest each carried a single mutation or in/del. Among the 34 de novo point mutations, 32 were predicted to be non-synonymous missense mutations and only 2 synonymous. Of the 32 non-synonymous mutations, 19 affect evolutionarily conserved residues and are predicted to affect protein function by PolyPhen-2. Three of the in/dels result in protein truncations and 1 in single aminoacid deletion. Additional query of de novo SNVs located within the flanking intronic regions identified 2 SNVs located within predicted donor/acceptor splice sites (Table 2). Interestingly, among the identified exonic SNVs, 1 synonymous and 3 non-synonymous ones were also located within predicted donor/acceptor splice sites (Table 2). Further analysis using the HSF tool (http://www.umd.be/HSF/) showed that 2 out of 6 mutations directly alter splice signals and may interfere with splicing (Table 2). By our filtering criteria all identified de novo mutations are absent in a total of 1,658 control chromosomes (the exomes of the 679 individuals from the 1,000 Genomes Project16 included in dbSNP132, as well as of all 150 unaffected parents in our 2 cohorts). Using the same pipeline and filtering criteria, we identified 7 exonic de novo SNVs but no in/del candidates in 7 out of 22 control subjects. Among these 7 de novo point mutations, 4 are predicted to be non-synonymous missense and 3 synonymous. In addition, we identified 1 de novo mutation within a predicted intronic splice site (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, 7 out of 22 controls carry at least one de novo event, with one control carrying more than one de novo mutation. The fraction is lower when compared to cases but the difference is not statistically significant (Fisher’s Exact Test, P value = 0.2). There was no difference in the coverage between cases and controls and between trios with and without de novo events (Supplementary Figure 4).

Table 2.

De novo mutations identified in 53 SCZ trios

| Gene Symbol | Mutation Type | NS vs S | Polyphen-2 | Grantham Score | phyloP Score | Chr:Pos | Nucleotide change | Aminoacid change | Diagnosis | Sex | Trio ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLCL2 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 112 | 4.99 | 3:17051253 | TGT-aGT | p.Cys30Ser | SCZ | M | trio_002 |

| WDR11 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 29 | 6.30 | 10:122664879 | CGC-CaC | p.Arg1081His | SCZ | M | trio_011 |

| DPYD | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 125 | 3.89 | 1:97981407 | GGA-aGA | p.Gly539Arg | SCZ | M | trio_016 |

| OR4C46 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 125 | 1.61 | 11:51515885 | GGA-aGA | p.Gly202Arg | SCZ | F | trio_019 |

| UGT1A3 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 15 | 0.53 | 2:234637866 | TTG-aTG | p.Leu32Met | SCZ | F | trio_023 |

| FAM3D | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 194 | 1.18 | 3:58622886 | TAC-TgC | p.Tyr147Cys | SCZ | M | trio_024 |

| KLF12 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 112 | 6.02 | 13:74289537 | TCT-TgT | p.Ser45Cys | SCZ | M | trio_033 |

| ADCY7 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 56 | 4.93 | 16:50349011 | AGC-gGC | p.Ser1020Gly | SCZ | M | trio_038 |

| GPR153 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 89 | 5.80 | 1:6314661 | ACC-AtC | p.Thr102Ile | SCZAFF-dpr | M | trio_040 |

| PML | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 81 | 2.93 | 15:74290439 | ACG-AtG | p.Thr75Met | SCZAFF-dpr | M | trio_044 |

| SLC26A8 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 56 | 1.87 | 6:35927251 | GAG-aAG | p.Glu512Lys | SCZAFF-bp | F | trio_077 |

| CCDC108 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 46 | 2.43 | 2:219900235 | AAT-AgT | p.Asn105Ser | SCZ | F | trio_080 |

| TRAK1 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 29 | 4.80 | 3:42261055 | CAT-CgT | p.His678Arg | SCZ | F | trio_083 |

| FASTKD5 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 60 | 5.61 | 20:3128479 | GCA-GgA | p.Ala413Gly | SCZ | M | trio_089 |

| DGCR2 | SNV | NS | probably damaging | 103 | 6.24 | 22:19028681 | CCT-CgT | p.Pro429Arg | SCZ | M | trio_091 |

| ACOT6 | SNV | NS | possibly damaging | 194 | -0.08 | 14:74086428 | TAT-TgT | p.Tyr170Cys | SCZ | F | trio_047 |

| PITPNM1 | SNV | NS/SPLICEa | probably damaging | 101 | 0.30 | 11:67267884 | CGG-tGG | p.Arg217Trp | SCZ | M | trio_039 |

| NPRL2 | SNV | NS/SPLICEb | possibly damaging | 56 | 6.11 | 3:50385987 | GGC-aGC | p.Gly231Ser | SCZ | F | trio_023 |

| MAGEC1 | SNV | NS | unknown | 58 | 0.37 | X:140993957 | ACT-AgT | p.Thr256Ser | SCZ | M | trio_003 |

| TRRAP | SNV | NS | unknown | 21 | 5.12 | 7:98498329 | ATC-tTC | p.Ile295Phe | SCZ | M | trio_033 |

| COL3A1 | SNV | NS/SPLICEc | unknown | 155 | 2.54 | 2:189851792 | TCT-TtT | p.Ser152Phe | SCZ | M | trio_089 |

| GIF | SNV | NS | benign | 29 | 0.83 | 11:59603474 | GTA-aTA | p.Val294Ile | SCZAFF-dpr | F | trio_001 |

| TEKT5 | SNV | NS | benign | 89 | 0.25 | 16:10783119 | ATC-AcC | p.Ile237Thr | SCZ | M | trio_011 |

| THBS1 | SNV | NS | benign | 56 | 5.66 | 15:39881442 | GAG-aAG | p.Glu605Lys | SCZ | M | trio_015 |

| PAG1 | SNV | NS | benign | 29 | 0.15 | 8:81905378 | GTC-aTC | p.Val29Ile | SCZ | M | trio_020 |

| RGS12 | SNV | NS | benign | 98 | 0.06 | 4:3429844 | CCA-CtA | p.Pro518Leu | SCZAFF-dpr | M | trio_040 |

| SAP30BP | SNV | NS | benign | 56 | 5.37 | 17:73702542 | GGC-aGC | p.Gly274Ser | SCZ | F | trio_047 |

| ZNF530 | SNV | NS | benign | 46 | -0.04 | 19:58118122 | AGT-AaT | p.Ser410Asn | SCZAFF-bp | F | trio_077 |

| MTOR | SNV | NS | benign | 46 | 2.82 | 1:11293489 | AAT-AgT | p.Asn796Ser | SCZ | F | trio_080 |

| INPP5A | SNV | NS | benign | 64 | 2.62 | 10:134463942 | GCG-GtG | p.Ala80Val | SCZAFF-bp | F | trio_093 |

| EDEM2 | SNV | NS | benign | 83 | 3.39 | 20:33703457 | TAC-cAC | p.Tyr469His | SCZ | M | trio_095 |

| CELF2 | SNV | S/SPLICEd | coding-synon | 3.06 | 10:11356223 | GGT-GGc | p.Gly345Gly | SCZ | M | trio_016 | |

| SLC26A7 | SNV | S | coding-synon | 0.03 | 8:92346630 | CAG-CAa | p.Gln250Gln | SCZ | M | trio_094 | |

| VPS35 | SNV | SPLICEe | - | - | 16:46705610 | C/T | SCZ | M | trio_002 | ||

| ADAMTS3 | SNV | SPLICEf | - | - | 4:73185683 | G/A | SCZ | F | trio_023 | ||

| GPR115 | DNV | NS | probably damaging | 99 | 3.35 | 6:47682855 | CTC-aaC | p.Leu625Asn | SCZ | F | trio_080 |

| SPATA5 | IN/DEL | AA DELETION | damaging | 215g | - | 4:123855728 | TTCTT-caa-CAACA | SCZ | F | trio_023 | |

| RB1CC1 | IN/DEL | FRAMESHIFT DELETION | damaging | 215 | - | 8:53568705 | ACTGT-tc-TCTGT | SCZ | M | trio_026 | |

| LAMA2 | IN/DEL | FRAMESHIFT DELETION | damaging | 215 | - | 6:129835668 | GGTGG-aagccca-AAGCC | SCZ | M | trio_092 | |

| ESAM | IN/DEL | FRAMESHIFT INSERTION | damaging | 215 | - | 11:124626163 | tggac-AGCG-agcgg | SCZ | M | trio_042 |

NS = Non-synonymous; S = Synonymous; SNV = single nucleotide variant; DNV = dinucleotide variant; SCZ = schizophrenia; SCZAFF-dpr = schizoaffective disorder depressed subtype; SCZAFF-bp = schizoaffective disorder bipolar subtype; M = Male; F = Female

HSF variation (%) between the reference and mutant sites:

−2.48;

56.53;

−0.68;

−34.92;

0;

−8.14

Maximum Grantham score (215) was used for the in/dels

The overall de novo rate in affected families (0.75 events per family) is comparable to several empirical estimates of the background de novo mutation rate8,16, suggesting that we identified most of the de novo events in these trios. Several lines of evidence suggest that the identified mutations have a high likelihood of causation with respect to SCZ. First, our screen yielded a ratio of non-synonymous missense (n = 32) to synonymous (n = 2) de novo changes (NS/S ratio) of 16:1, which is considerably higher than the 2.85:1 ratio expected based on the probability of causing an aminoacid change under a random model (71.25% non-synonymous missense substitutions and 25% synonymous17 ). By contrast, the ratio of non-synonymous missense (n = 4) to synonymous (n = 3) de novo changes in the control cohort (NS/S ratio of 1.33:1) is consistent to neutral expectation and very close to the NS/S ratio reported by the 1,000 Genome Project (1.14 – 1.45)16. Second, non-synonymous de novo point mutations were found in large excess compared to neutral ones relative to rare inherited variants, which are less likely to contribute to the pathogenesis of the sporadic cases (Table 3). Specifically, we first compared the relative enrichment of non-synonymous de novo point mutations to the one observed among all novel (i.e. not observed in dbSNP132) inherited variants segregating in cases. Our analysis revealed a NS/S substitution ratio of 1.61:1, consistent with previous analysis of normal genetic variation16,18. Thus, in sporadic SCZ cases, rare de novo variants are ~10 times more likely than inherited rare variants to harbor non-synonymous changes (Chi-square test, P = 0.0002). A similar analysis in the control cohort did not reveal significant differences. The NS/S ratio was 1.33 and ~1.60 for rare de novo and inherited variants, respectively (relative enrichment 0.83; Chi-square, P = 0.81). We obtained similar results when we limited the analysis to the private inherited variants (i.e. present only in one affected family), which serve as a proxy for evolutionarily young mutation events. This analysis yielded a NS/S ratio of ~ 1.69:1 in cases (relative enrichment 9.5; Chi-square test, P = 0.0003) and ~1.74 in controls (relative enrichment 0.76; Chi-square test, P = 0.73). Consistent with expectations that disease mutations have a greater impact on protein function19, we observed a more striking enrichment when we restricted our analysis to non-synonymous SNVs predicted by PolyPhen-2 to affect protein function. For such changes, the NS/S ratio in SCZ cases is 9.5 and ~ 0.79 for rare de novo and private inherited variants, respectively (relative enrichment 12.1; Chi-square test, P < 0.0001).

Table 3.

NS/S ratio comparison between de novo and rare inherited mutations in SCZ trios

| Cases | Controls | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Class | Total Number | NS | S | NS/S | P value (de novo vs inherited) | Total Number | NS | S | NS/S | P value (de novo vs inherited) |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| de novo mutations | 34 | 32 | 2 | 16 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 1.33 | ||

| novel inherited mutations | 14378 | 8867 | 5511 | 1.61 | 0.0002 | 6213 | 3825 | 2388 | 1.60 | 0.81 |

| private inherited mutations | 6727 | 4223 | 2504 | 1.69 | 0.0003 | 3079 | 1956 | 1123 | 1.74 | 0.73 |

S = Synonymous mutations

NS = Non-synonymous mutations

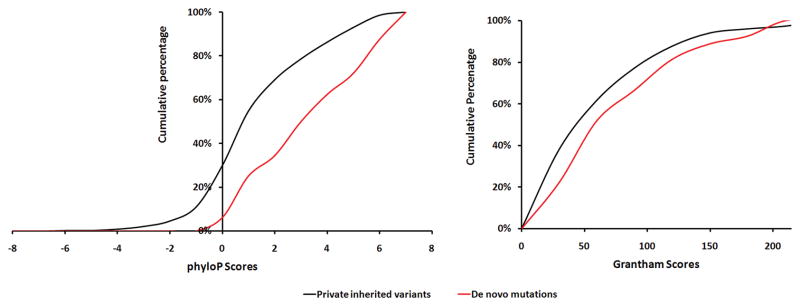

We explored further the possibility that de novo mutations in cases have a greater potential to affect protein structure and function than private inherited variants by examining the evolutionary conservation of affected nucleotides (using the phyloP score20), as well as the potential of the de novo protein-altering mutations to affect the structure or function of the resulting proteins (using the Grantham score21) (Table 2). When we compared the cumulative distribution of these scores between de novo and private inherited variants in the sporadic cases cohort (Figure 1) we observed that the distribution of the de novo variants was clearly shifted to the right (phyloP, P = 0.0005; Grantham, P = 0.14). Overall, our analysis reveals an enrichment of highly conserved and disruptive aminoacid mutations among de novo events and suggests a high likelihood for pathogenicity. Notably, carriers of one or more de novo mutations appear to be indistinguishable from other SCZ patients in terms of sex distribution, clinical presentation and developmental course (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1. The potential of de novo SNVs in cases to affect protein function.

Comparison of the distribution of phyloP scores (which depend on the evolutionary conservation of affected nucleotides) (A) and Grantham scores (which depend on the properties of the changed residue) (B) among de novo mutations and private inherited variants in SCZ cases.

All mutations occurred in different genes, precluding statistical assessment for any specific locus. Identification of recurrent mutations will provide definitive proof for disease causality. With one exception, none of the affected genes have been previously associated with genetic loci or biological pathways unequivocally associated with SCZ. We therefore used phyloP and Grantham scores as a guide to prioritize for further discussion events that are more likely to be causal. In addition to protein truncating in/dels (in LAMA2, SPATA5, RB1CC1) there are 12 SNVs with phyloP scores ≥ 4 and 9 SNVs with Grantham score ≥ 100, while 3 SNVs (in DGCR2, KLF12 and PLCL2) show high values for both scores (see Table 2). Most notable among the putative pathogenic events is a p.Pro429Arg substitution in DGCR2 in a male patient with SCZ (see Supplementary Information). DGCR2 is located in the 22q11.2 locus and is hemizygously deleted by recurrent de novo microdeletions at this locus, which have high penetrance (~30%) and account for up to 2% of sporadic SCZ cases. The gene encodes a putative transmembrane adhesion receptor of unknown function22. The p.Pro429Arg substitution is located within a conserved domain of the protein (Supplementary Figure 2) and shows one of the highest Grantham and phyloP scores among all identified changes. Identification of a disruptive de novo SNV in the DGCR2 gene, in a patient with structurally intact 22q11.2 chromosomes suggests that disruption of this gene may be contributing to the elevated SCZ risk associated with the 22q11.2 locus. Whether heterozygous deletions or point mutations in the DGCR2 are sufficient to render the susceptibility to SCZ observed in 22q11.2 microdeletion carriers or whether additional genetic interactions are required23, cannot be resolved until more DGCR2 mutations are identified and their penetrance is determined. Additional putative pathogenic events were identified in three G-protein coupled receptors (GPRs: GPR153, GPR115 and OR4C46)24,25 as well as in genes encoding proteins thought to either modulate (i.e. RGS12) or mediate aspects of GPR signaling, such as regulation of cAMP levels (i.e. ADCY726). Notably, we have recently reported an association between SCZ and structural de novo mutations in another GPR (VIPR2)27 and showed that these mutations alter cAMP levels. For other genes with high phyloP or Grantham scores. such as WDR11, PLCL2, TRAK1, KLF12 and LAMA2, evidence for a potential causal link with SCZ is provided by literature on previously described mutations, model organisms and other functional studies (Supplementary Information).

Our work conclusively demonstrates that de novo protein-altering mutations contribute substantially to the genetic component of SCZ and, taken together with previous estimates of the de novo CNV rate in the same population6, it indicates that de novo mutations account for more than half of the sporadic cases of SCZ. Our findings are also in line with results from genome-wide scans for de novo CNVs6,28 or CNVs in general29,30 supporting the notion that multiple de novo genetic variants that affect many different genes contribute to the genetic risk of SCZ. The complexity of the neural substrates affected in SCZ and other psychiatric disorders offers a large mutational target comprised of many genes. We propose that this large number of targets that, when mutated, can give rise to SCZ along with the relatively high rate of protein-altering mutations, empirically demonstrated in the present study, provides a plausible explanation for both the high global incidence and the persistence of SCZ despite extremely variable environmental factors, severely reduced fecundity and increased mortality. Our findings represent a decisive step towards understanding the pathogenesis of the disease and emphasize the challenge in determining the neural substrates that these diverse genetic risk factors converge upon to generate a common pattern of clinical dysfunction and symptoms23,31–34.

METHODS

Cohorts

All 53 SCZ families were recruited from the Afrikaner population in South Africa and heritage was established by surname and by having 4 Afrikaans-speaking grandparents. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Institutional Review Committees of Columbia University and University of Pretoria approved all procedures. Diagnostic evaluations were done in person, as previously described6,13. Family history was obtained from the proband, each participating parent, and additional relatives as needed, by two independent raters, a nursing sister, who recorded pedigree information, and by the clinical interviewer, who inquired in detail about family history during the clinical interview6,13. For additional cohort characteristics, see Supplementary Information. The control cohort consisted of 22 families (triads) with established Afrikaner heritage recruited from the Afrikaner community. Paternity and maternity were confirmed prior to sequencing for all case and control families via the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 5.06,13 as well as via a panel of microsatellite markers.

Exome library construction

Exome enrichment was conducted using the SureSelect Human All Exon Target Enrichment System (Agilent Technologies) based on the methodology described in35. Briefly, 3 ug of genomic DNA was fragmented by sonication using the Covaris S2 to achieve a uniform distribution of fragments with a mean size of 300 bp. The sonicated DNA was purified using Agencourt’s AMPure XP Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization paramagnetic bead (SPRI) followed by polishing of the DNA ends by removing the 3′ overhangs and filling in the 5′ overhangs resulting from sonication using T4 DNA polymerase and Klenow fragment (New England Biolabs). Following end polishing, a single ‘A’-base was added to the 3′ end of the DNA fragments using Klenow fragment (3′ to 5′ exo minus). This prepares the DNA fragments for ligation to specialized adaptors that have a ‘T’-base overhang at their 3′ends. The end-repaired DNA with a single ‘A’-base overhang is ligated to the Illumina paired-end adaptors in a standard ligation reaction using T4 DNA ligase and 2 uM – 4 uM final adaptor concentration, depending on the DNA yield following purification after the addition of the ‘A’-base. Following ligation, the samples were purified using SPRI beads, quality controlled by assessment on the Agilent Bioanalyzer and then amplified by 6 cycles of PCR to maintain complexity and avoid bias due to amplification.

Library capture and sequencing

500 ng of amplified, purified DNA (DNA library) was prepared for hybridization by adding the DNA library to Agilent blocking reagents, denaturing at 95 °C and incubating at 65 °C. All subsequent steps were performed at 65 °C. Hybridization buffer was added to the prepared library and the entire mix was then added to an aliquot of the Agilent SureSelect Capture Library and mixed. The DNA library and biotin-labeled Capture Library were hybridized by incubation at 65 °C for 24 hours. Following hybridization, streptavidin coated magnetic beads were used to purify the RNA:DNA hybrids formed during hybridization. The RNA capture material was digested via acid hydrolysis following elution from the purification beads. The neutralized captured DNA was purified, desalted and amplified by 12 cycles of PCR using Herculase II Fusion DNA polymerase. The libraries were purified following amplification and the library was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer. A single peak between 300 – 400 bp indicates a properly constructed and amplified library ready for sequencing. Final quantitation of the library was performed using the Kapa Biosciences Real-time PCR assay and appropriate amounts of the library were loaded onto the Illumina flowcell for sequencing by paired-end 50 nt sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument. Sequencing was performed largely as described in16. Following dilution to 10 nM final concentration based on the real-time PCR and bioanalyzer results, the final library stock was then used in paired-end cluster generation at a final concentration of 6 – 8 pM to achieve a cluster density of 600,000/mm2 (on the Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument). Following cluster generation, 50 nt paired-end sequencing was performed using the standard Illumina protocols.

Exome data analysis for de novo coding point mutations, in/dels and splice site mutations

Raw sequencing data for each individual were mapped to the human reference genome (build hg19) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA v0.5.81536)14. The BWA aligned sequencing reads were processed by Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net/) to label the PCR duplicates. The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, version 5091) was then used to remove duplicates, perform local realignment and map quality score recalibration to produce a “cleaned” BAM file for each individual. SNP calls were made by the Unified Genotyper module in GATK using the “cleaned” BAM files in batch fashion (90 samples per batch). The resulting Variant Call Format (VCF, version 4.0) files were annotated using the GenomicAnnotator module in GATK to identify and label the called variants that are within the targeted coding regions and overlap with known and likely benign SNPs reported in dbSNP v132 (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/organisms/human_9606/VCF/v4.0/00-All.vcf.gz). The annotated VCF files were then filtered using the GATK variant filter module with a hard filter setting and a custom script for initial filtering. Variant calls that failed to pass the following filters were eliminated from the call set: i) MQ0 >= 4 && ((MQ0/(1.0 * DP)) > 0.1); ii) QUAL < 30.0 || QD < 5.0 || HRun > 5 || SB > 0.00; iii) Cluster size 10; iv) Contain dbSNP id; v) Outside the targeted regions. Combined VCF files were then split into individual files and variants in each offspring were compared to variants present in parents using a custom script pipeline in order to determine the inheritance pattern and annotate de novo mutations.

Because the GATK Unified Genotyper is set to maximize the sensitivity of variant calls, it allows for a significant portion of false positives among candidate variants even following the initial filtering process. To address this issue and eliminate potential false positive calls in the offspring and false negative calls in the parents, we took advantage of the inheritance information provided by our family design and revalidated all variants identified using the mpileup module in the SAM tools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/) according to the following rules: i) the forward reference (fr) count (i.e. the number of forward reads that match the reference base at this locus), the reverse reference (rr) count (i.e. the number of reverse reads that match the reference base at this locus), the forward non reference (fnr) count (i.e. the number of forward reads that do not match the reference base at this locus) and the reverse non reference (rnf) count (i.e the number of reverse reads that do not match the reference base at this locus) in the offspring must be 2 or greater; ii) total read depth in both parents must be 10 or greater; iii) both fr and rr count in both parents must be 2 or greater; iv) either fnr or rnr count in both parents must be 0; v) The fnr and rnr count to total count ratio in the parental population (defined as all 150 parental samples sequenced) must be less than 1/2n, where n is the population size; vi) If any of rules 1–5 was violated, the sequence information was considered insufficient to make a de novo call at this locus.

In/del calls were made by the Dindel software using one “cleaned” BAM file per run. The resulting VCF files were used to determine inheritance patterns using the same procedure described above for point mutations. To determine potential mutations at splice-donor or acceptor sites, GATK variant calls were made in a batch fashion (with 90 samples per batch) that covered each target coding region and 50 bp flanking segments in each direction. The variants in the resulting VCF files were annotated according to ftp://gatk-ftp:PH5UH7Pa@ftp.broadinstitute.org/refGene/refGene-big-table-hg19.txt.gz.

The PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) online server was used to determine the non-synonymous and synonymous nature of the mutations and predict their functional impact by further classifying them as non-tolerated (damaging) or benign at a given site. The Grantham score for each coding variant was determined by the Grantham matrix table21. The phyloP score for each coding variant was extracted from the “phyloP46wayAll” table in the UCSC Table Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables). The Human Splicing Finder (HSF, Version 2.4.1) software (http://www.umd.be/HSF/) was used to predict potential functional impact of the mutations at splice sites.

Statistics

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (KS-test) was used to compare the distribution of phyloP and Grantham scores among de novo or private inherited mutations in cases. The KS-test was conducted using R (www.r-project.org/). Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test with Yates’ correction was used for the analysis of contingency tables depending on the sample sizes.

De novo mutation validation

Candidate de novo variants were tested using standard Sanger sequencing on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer to validate presence of each mutation in the subjects and absence in the parental genomes, by designing custom primers (Sigma) based on ~500 bp of genomic sequence flanking each variant. De novo occurrence of mutations was not confirmed in 6 out of 46 and 2 out of 9 candidate alterations in cases and controls, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the families who participated in this research. We also thank H. Pretorius and nursing sisters R. van Wyk, C. Botha and H. van den Berg for their assistance with subject recruitment, family history assessments and diagnostic evaluations. We thank Yan Sun for technical assistance with DNA extractions and sample preparations and Joseph Grun for IT support. We also thank Emily Fledderman and Stephen Thomas for support of the sequencing studies, and Melanie Robinson for critical project support. This work was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants MH061399 (to M.K.) and MH077235 (to J.A.G.) and the Lieber Center for Schizophrenia Research at Columbia University. BX was partially supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award.

Footnotes

URLs:

Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net/)

SAM tools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/)

PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/)

UCSC Table Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables)

The Human Splicing Finder (HSF, Version 2.4.1) software (http://www.umd.be/HSF/)

dbSNP v132 (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/organisms/human_9606/VCF/v4.0/00-All.vcf.gz)

GATK VCF annotation file for hg19 (ftp://gatk-ftp:PH5UH7Pa@ftp.broadinstitute.org/refGene/refGene-big-table-hg19.txt.gz)

Accession codes: Reference sequences are available from NCBI under the following accession codes: PLCL2, NM_001144382; WDR11, NM_018117; DPYD, NM_000110; OR4C46, NM_001004703; UGT1A3, NM_019093; FAM3D, NM_138805; KLF12, NM_007249; ADCY7, NM_001114; GPR153, NM_207370; PML, NM_002675; SLC26A8, NM_052961; CCDC108, NM_152389; TRAK1, NM_001042646; FASTKD5, NM_021826; DGCR2, NM_005137; ACOT6, NM_001037162; PITPNM1, NM_001130848; NPRL2, NM_006545; MAGEC1, NM_005462; TRRAP, NM_003496; COL3A1, NM_000090; GIF, NM_005142; TEKT5, NM_144674; THBS1, NM_003246; PAG1, NM_018440; RGS12, NM_002926; SAP30BP, NM_013260; ZNF530, NM_020880; MTOR, NM_004958; INPP5A, NM_005539; EDEM2, NM_001145025; CELF2, NM_001083591; SLC26A7, NM_134266; VPS35, NM_018206; ADAMTS3, NM_014243; GPR115, NM_153838; SPATA5, NM_145207; RB1CC1, NM_014781; LAMA2, NM_000426; ESAM, NM_138961

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

BX, JAG and MK designed the study, interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript; BX developed the analysis pipeline and had the primary role in analysis and validation of sequence data; JLR collected the samples and was the primary clinician on the project; SL and BP performed exome library construction, capture and sequencing; PD contributed to the analysis of the data; BB contributed to the primary sequence data analysis; SL supervised the sequencing project at HudsonAlpha Institute and contributed to the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Gottesman II, Shields J. A polygenic theory of schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;58:199–205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1187–92. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein P, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373:234–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lupski JR. Genomic rearrangements and sporadic disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:S43–7. doi: 10.1038/ng2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karayiorgou M, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility associated with interstitial deletions of chromosome 22q11. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7612–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu B, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:880–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirulli ET, Goldstein DB. Uncovering the roles of rare variants in common disease through whole-genome sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:415–25. doi: 10.1038/nrg2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Roak BJ, et al. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ng.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vissers LE, et al. A de novo paradigm for mental retardation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1109–12. doi: 10.1038/ng.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awadalla P, et al. Direct measure of the de novo mutation rate in autism and schizophrenia cohorts. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:316–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abecasis GR, et al. Genomewide scan in families with schizophrenia from the founder population of Afrikaners reveals evidence for linkage and uniparental disomy on chromosome 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:403–17. doi: 10.1086/381713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karayiorgou M, et al. Phenotypic characterization and genealogical tracing in an Afrikaner schizophrenia database. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;124B:20–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu B, et al. Elucidating the genetic architecture of familial schizophrenia using rare copy number variant and linkage scans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16746–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908584106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentley DR, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durbin RM, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch M. Rate, molecular spectrum, and consequences of human mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:961–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912629107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, et al. Resequencing of 200 human exomes identifies an excess of low-frequency non-synonymous coding variants. Nat Genet. 2010;42:969–72. doi: 10.1038/ng.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botstein D, Risch N. Discovering genotypes underlying human phenotypes: past successes for mendelian disease, future approaches for complex disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33 (Suppl):228–37. doi: 10.1038/ng1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard KS, Hubisz MJ, Rosenbloom KR, Siepel A. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome Res. 2010;20:110–21. doi: 10.1101/gr.097857.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science. 1974;185:862–4. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4154.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kajiwara K, et al. Cloning of SEZ-12 encoding seizure-related and membrane-bound adhesion protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:144–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karayiorgou M, Simon TJ, Gogos JA. 22q11.2 microdeletions: linking DNA structural variation to brain dysfunction and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:402–16. doi: 10.1038/nrn2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjarnadottir TK, et al. The human and mouse repertoire of the adhesion family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Genomics. 2004;84:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gloriam DE, Schioth HB, Fredriksson R. Nine new human Rhodopsin family G-protein coupled receptors: identification, sequence characterisation and evolutionary relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1722:235–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz MT, et al. Type 7 Adenylyl Cyclase is Involved in the Ethanol and CRF Sensitivity of GABAergic Synapses in Mouse Central Amygdala. Front Neurosci. 2011;4:207. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vacic V, et al. Duplications of the neuropeptide receptor gene VIPR2 confer significant risk for schizophrenia. Nature. 2011;471:499–503. doi: 10.1038/nature09884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefansson H, et al. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ISC. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh T, et al. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fenelon K, et al. Deficiency of Dgcr8, a gene disrupted by the 22q11.2 microdeletion, results in altered short-term plasticity in the prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4447–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101219108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sigurdsson T, Stark KL, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA, Gordon JA. Impaired hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony in a genetic mouse model of schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;464:763–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arguello PA, Gogos JA. Cognition in mouse models of schizophrenia susceptibility genes. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:289–300. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arguello PA, Gogos JA. Modeling madness in mice: one piece at a time. Neuron. 2006;52:179–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gnirke A, et al. Solution hybrid selection with ultra-long oligonucleotides for massively parallel targeted sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:182–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.