Abstract

Research has documented a relation between parents’ ethnic socialization and youth’s ethnic identity, yet there has been little research examining the transmission of cultural values from parents to their children through ethnic socialization and ethnic identity. This study examines a prospective model in which mothers’ and fathers’ Mexican American values and ethnic socialization efforts are linked to their children’s ethnic identity and Mexican American values, in a sample of 750 families (including 467 two-parent families) from an ongoing longitudinal study of Mexican American families (Roosa, Liu, Torres, Gonzales, Knight, & Saenz, 2008). Findings indicated that the socialization of Mexican American values was primarily a function of mothers’ Mexican American values and ethnic socialization, and that mothers’ Mexican American values were longitudinally related to children’s Mexican American values. Finally, these associations were consistent across gender and nativity groups.

Keywords: cultural values, ethnic socialization, Mexican American families, ethnic identity

In recent years there has been an increasing interest in the impact of the cultural adaptation of ethnic minority youths on their mental health, academic outcomes, and resilience (see Gonzales, Fabrett, & Knight, 2009 for a review). One subset of this literature has focused on the role of ethnic or cultural socialization in the culturally related behavior of Latino youths (e.g., Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006; Knight, Cota, & Bernal, 1993). Although there is a relatively small empirical literature bearing on the changes experienced by Mexican American (or other Latino) youths resulting from ethnic socialization, much of this has focused on the relations between socialization experiences and ethnic identity (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). Much less is known about the familial transmission of culturally related values, even though such values guide behavior in a wide range of contexts and are considered prime targets in the socialization of cultural orientation (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, & Cota, 1993; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009). The present study is designed to prospectively examine the process through which values linked to Mexican American culture are transmitted from parents to Mexican American youths through ethnic socialization within the family, as well as the role that youths’ ethnic identity plays in the adoption of these values.

The development of a strong ethnic identity has consistently been associated with positive psychological outcomes among adolescents (e.g., Armenta, Knight, Carlo, & Jacobson, 2010; Fuligni, Witkow, & Garcia, 2005; Phinney, 1990; Supple et al., 2006). There is also an emerging literature focused on the role of ethnic socialization in the transmission of culturally related values in Latino families (Berkel, Knight, Zeiders, Tein, Roosa, Gonzales, & Saenz, 2010; Calderón-Tena, Knight, & Carlo, 2011; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009) and the relation of these values to adjustment (e.g., Berkel et al., 2010; Calderón-Tena et al., 2011).

This research is based on theoretical models (Knight, Bernal, Garza, & Cota, 1993; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004) that emphasize broader cultural and contextual factors including both familial and non-familial socialization agents. Given the plethora of research indicating that family members, and particularly parents, are the foremost source of information about ethnicity for youths (Brown, Tanner-Smith, Lesane-Brown, & Ezell, 2007; Hughes et al., 2006; Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009), we focused on the familial context, including the parent’s nativity, the ethnic values endorsed by parents, and parents’ ethnic socialization efforts. Theoretical models of ethnic socialization also highlight developmental differences in the specific features of ethnic identity that are salient at different development stages. During early childhood, ethnic socialization may foster the development of behaviors (such as Spanish language use), ethnic self identification (awareness that one is a member of an ethnic group), ethnic constancy (awareness that one’s ethnicity is permanent), ethnic knowledge, and ethnic preferences (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993). The greater social and cognitive capabilities associated with adolescence may allow ethnic socialization to foster more advanced features of ethnic identity such as ethnic identity exploration (the degree to which one has tried to learn more about their ethnic group), and resolution (the degree to which one has clarified the role that ethnic identity plays in their life; e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). Further, the development of ethnic identity exploration and resolution (which are associated with parents’ ethnic socialization; e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004) may foster or be requisite for the internalization of values associated with the ethnic culture. Hence, this research is designed to examine a model suggesting that Mexican American mothers and fathers born in Mexico are more likely to endorse Mexican American values and engage in more ethnic socialization of their early adolescent children. This ethnic socialization will foster a stronger ethnic identity in their adolescent children (particularly ethnic exploration and ethnic resolution), which in turn will lead these adolescents to increased endorsement of Mexican American values.

Although there is literature associating ethnic socialization with ethnic identity, and an emerging literature on the linkage between ethnic socialization and culturally related values, there has been little examination of the ways in which the formation of ethnic identity is associated with the development of culturally related values. Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) suggests that the activation of any particular social identity in a given immediate situation leads to attitudes, expectations, and values associated with that social identity becoming the guiding force for behavior in that situation. In addition, self categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987) suggests that the activation of a social identity increases the tendency to self stereotype, which enhances perceptions of oneself as being more similar to a stereotypic or prototypic member of one’s group. Self stereotyping, in turn, enhances the tendency to adopt group norms and engage in behaviors that are consistent with such norms (e.g., Oyserman & Lee, 2008). Together, these theories suggest that Mexican American youths’ degree of ethnic identification may determine the extent to which they are likely to internalize values associated with Mexican American culture because of their greater commitment to, and exploration of, their ethnic group membership. Indeed, this perspective is consistent with the evidence indicating that ethnic identity and the adoption of values associated with Mexican American culture are related (Armenta et al., 2010; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009). In addition, the search for the meaning of their ethnic group membership (i.e., ethnic exploration) may be required to discern the nature of the cultural values associated with the ethnic group, and ethnic group membership being an important element of one’s self concept (i.e., ethnic resolution) may be necessary to make a commitment to these culturally related values. If so, it is reasonable to expect that the development of more advanced features of ethnic identity, such as ethnic identity exploration and resolution, may foster the internalization of culturally related values. Indeed, Kiang and Fuligni (2009) used longitudinal data to support this hypothesized direction of the relation between ethnic identity and culturally related values.

Although there is existing research examining portions of this socialization model, this research has been based upon single time point assessment, generally based upon only single reporter data (usually adolescents), and rarely considered father’s contributions to the socialization of their children’s values. The present research is based upon prospective analyses of longitudinal data because this model proscribes that ethnic socialization leads to changes in culturally related values over time. In addition, this research examines the role of ethnic identity in the adoption of culturally related values. We also conducted multi-group analyses to examine the degree to which this model was moderated by the youth’s gender because there is some evidence, albeit mixed, suggesting that ethnic socialization effects may vary across youth characteristics (Brown et al., 2007; Hughes et al., 2006, Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009). Finally, to provide a more rigorous test of the directional effects hypothesized, several alternative models were tested as follows: (a) whether mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization uniquely informed youth’s ethnic identity or whether their interactive influence would be more informative; (b) whether mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization efforts informed youth’s ethnic identity and, in turn, youths’ values (i.e., ethnic identity as a mediator), or whether ethnic identity is independent of parents’ socialization efforts and independently informs the strength of the association between parents’ socialization and youth values (i.e., ethnic identity as a moderator); and (c) whether the direction of effect is from youth’s ethnic identity to youth’s values or from youths’ values to youths’ ethnic identity. The paths in our hypothesized model were all conceptually derived, and testing these alternative mechanisms provided an opportunity to rule out alternate processes that could explain the associations of interest.

Method

Participants

Data for this study come from the first and second assessments (between 2004 and 2008) of an ongoing longitudinal study investigating the role of culture and context in the lives of Mexican American families (Roosa et al., 2008). Participants were 750 Mexican American adolescents, their mothers, and 467 (62.3%) of their fathers, who were selected from rosters of schools that served ethnically and linguistically diverse communities in the Phoenix metropolitan area. To recruit a representative sample of Mexican American families, a multiple step process was implemented that included: a stratified random sampling strategy to select neighborhoods diverse in cultural and economic qualities, recruitment through 47 schools across 35 neighborhoods, the use of culturally sensitive recruitment and data collection processes, conducting interviews in participants’ homes in English or in Spanish according to the participants’ preference, and a financial incentive (Roosa et al., 2008). After receiving consent to contact families through a letter to the home we attempted to contact 1,982 families. Of these, 12 (0.6%) families could not be contacted, 55 (2.8%) declined to participate before being screened, and 1,970 were screened to determine if they met the eligibility requirements. Of the 1,085 who met the eligibility requirements 750 (69.1%) completed the initial interview, 270 (24.9%) declined to participate, 4 (0.3%) began the interview but were unable to complete it, and 61 (5.6%) were not asked to participate because we had reached our recruitment goal. Of those who were ineligible: 56 (2.8%) no longer attended the participating school, 99 (5.0%) and 243 (12.3%) did not have a biological mother or father (respectively) in the home, 298 (15.1%) and 106 (5.4%) did not have a Mexican American biological mother or father (respectively), 16 (0.8%) were severely learning disabled, 3 (.01%) could not speak either English or Spanish, and 9 (.04%) were participating in another research project. Hence, the overall recruitment success was 73.2% of those who were eligible and asked to participate. The resulting sample was diverse in cultural orientation, social class, and type of residential neighborhoods, and similar to the census description of this population. The participating families included both a biological mother and father (if willing) who self identified as Mexican or Mexican American and fifth grade adolescent that lived with the mother and that was not severely learning disabled. No stepfather or mother’s boyfriend was living with the adolescent (unless the boyfriend was the biological father of the target adolescent).

This sample of Mexican American families was diverse with respect to both SES and language (Roosa et al., 2008). Family incomes ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $95,000, with the average family reporting an income of $30,000 – $35,000. In terms of language, 30.2% of mothers, 23.2% of fathers, and 82.5% of adolescents were interviewed in English. The mean age of mothers in our study was 35.9 (SD = 5.81) and mothers reported an average of 10.3 (SD = 3.67) years of education. The mean age of fathers was 38.1 (SD = 6.26) and fathers reported an average of 10.1 (SD = 3.94) years of education. The adolescents (48.7% female) ranged in age from 9 to 12 with a mean of 10.42 (SD = .55; with 97.6% being 10 or 11 years old) at Time 1. A majority of mothers and fathers were born in Mexico (74.3%, 79.9%, respectively), and a majority of adolescents were born in the United States (70.3 %).

At Time 2, approximately two years after Time 1 data collection, most students were in the 7th grade. Of the 39 (5.2%) families who did not participate at Time 2, 16 (2.1%) refused to participate. Families who participated at Time 2 were compared to families who did not participate at Time 2 on several Time 1 demographic variables and no differences emerged on adolescent (i.e., gender, age, generational status, language of interview), mother (i.e., marital status, age, generational status), or father characteristics (i.e., age, generational status).

Procedure

Mothers, fathers, and adolescents completed computer assisted personal interviews at their home, scheduled at the family’s convenience, that were about 2.5 hours long. Cohabiting family members’ interviews were conducted concurrently by trained interviewers in separate locations at participants’ homes to ensure confidentiality. The interviewers were: 80–90% female (depending upon the assessment year), between 23 and 60 years of age (with the exception of a 19 year old civil rights activist), fluent in both English and Spanish, recipients of a master’s or bachelor’s degree (or the combination of education and a least 2 years of professional experience in a social service agency), strong in communication and organizational skills, and knowledgeable about computers. Each interviewer received at least 40 hours of training which included information on the project’s goals, characteristics of the target population, the importance of professional conduct when visiting participants’ homes as well as throughout the process, and the critical role they would play in collecting the data. Interviewers read each survey question and possible responses aloud in participants’ preferred language to reduce problems related to variations in literacy levels. Families were compensated $45 and $50 per participating family member at Time 1 and 2, respectively.

Measures

Nativity

In response to the question “In what country were you born?” mothers and fathers were asked to select among three possible options (the United States, Mexico, or other). Mothers were also asked to report on the country of birth of their participating child using these options.

Mexican American values

Mothers, fathers, and adolescents completed the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS: Knight, Gonzales, Saenz, Bonds, Germán, Deardorff, Roosa, & Updegraff, 2010) to assess Mexican American values. The MACVS was developed based upon focus groups conducted with Mexican American mothers, fathers, and adolescents about the Mexican American and mainstream American cultures. The current study used 5 subscales from this measure to assess adolescents’ Mexican American values: Familism-Support (6 items, e.g., “parents should teach their children that the family always comes first”); Familism-Obligation (5 items, e.g., “if a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible”); Familism-Referents (5 items, e.g., “a person should always think about their family when making important decisions”); Respect (8 items, e.g., “children should always be polite when speaking to any adult”); and Religiosity (7 items, e.g., “one’s belief in God gives inner strength and meaning to life”). Each family member indicated their endorsement of each item by responding with a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) not at all to (5) very much. Confirmatory factor analyses using the first assessment in this data set indicated that the items for each subscale fit best on the respective subscale and that these subscales also loaded on a higher order factor (Knight et al., 2010). In addition, these confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the factor loading for each item and the loading of each subscale on the higher order Mexican American values latent construct were comparable for adolescents, mothers, and fathers. Cronbach’s α for mothers T1, fathers T1, adolescents T1, and adolescents T2 were .86, .89, .87, and .89 respectively. The MACVS also includes Mainstream values scales (Material Success, Independence and Self-Reliance, and Competition and Personal Achievement) that were not included in this report because we did not have assessments of mainstream socialization or mainstream identity.

Ethnic socialization

Mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization was assessed with an adaptation of the 10-item Ethnic Socialization Scale from the Ethnic Identity Questionnaire (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993). This measure was designed to assess ethnic socialization about cultural traditions, values, beliefs, and ethnic group history. The adaptation was designed to eliminate items more appropriate for youths younger than those in the present study and to generate a few items specifically focused on the socialization of values that have been associated with a Mexican heritage (Knight et al., 2010). Mothers and fathers were asked to indicate, using a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) almost never or never to (5) a lot of the time (frequently), how often had they socialized their adolescent children about the Mexican American culture. Sample items included: “How often do you: “tell your child to be proud of his/her Mexican background”; “tell your child that he/she always has an obligation to help members of the family”; and “tell your child about the discrimination she/he may face because of her/his Mexican background.” Cronbach’s α was .76 for mothers and .79 for fathers.

Ethnic identity

Adolescents’ ethnic identity was assessed with the 17-item Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004), which includes three subscales that measure exploration (7 items), resolution (4 items), and affirmation (6 items). Adolescents were asked to indicate how true each item was using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) not at all true to (5) to very true. Because the EIS is designed to be administered to diverse ethnic samples, items were slightly revised for the current study to be specific to individuals of Mexican origin. Sample items included: “You have attended events that have helped you learn more about your Mexican/Mexican American background” (exploration), “You have a clear sense of what your Mexican/Mexican American background means to you” (resolution), and “You wish you were of a cultural background that was not Mexican/Mexican American” (affirmation, reverse scored). Cronbach’s α for adolescents was .73, .86, and .76 for the exploration, resolution, and affirmation subscales, respectively. Although the affirmation subscale has a reasonable internal consistency, confirmatory factor analyses and construct validity analyses have led to the suggestion that the reverse wording of all of the items on this subscale may be problematic among the relatively young adolescent Mexican Americans in this sample (White et al., 2010). Hence, the affirmation subscale of the EIS was not included in the current analyses.

Analysis Plan

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analyses were conducted using the full information maximum likelihood estimation procedures available in Mplus Version 5.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2008) to handle missing data. Other than the very small attrition of families between the initial and second assessment (described earlier) there was less than .2% missing data for any single item in the assessment battery. In all models, Mexican American values, ethnic socialization, and ethnic identity were treated as latent variables. Adolescents’ reports of their Mexican American values at Time 1 were included in the models to enable the prediction of change in Mexican American values over time. To control the number of paths being estimated because of the large number of items on each subscale other than ethnic socialization, the subscales of each multi-subscale latent construct were treated as observed variables. For ethnic socialization the individual items were used to create the latent construct. The factor loadings of all items on each subscale were significant and above .50, indicating the adequacy of the measurements. Nativity, Mexican American values, and ethnic socialization were allowed to correlate across mothers and fathers within each family for all models. Multiple practical fit indices (CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR) were used to evaluate the extent to which the model fit the data because no single indicator is unbiased in all analytic conditions. Model fit was considered good (acceptable) if the SRMR ≤ .05 (.08) and either a RMSEA ≤ .05 (.08) or a CFI ≥ .95 (.90) because simulation studies revealed that using this combination rule resulted in low Type I and Type II error rates (Hu & Bentler, 1999). To more rigorously examine the hypothesized direction of effects, several alternative models were examined following the tests of the hypothesized model. The reported findings are based upon the 750 mother/adolescent pairs and 467 participating fathers, however, analyses of only the families with two participating parents produced nearly identical findings.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables included in the model. Table 2 presents the direct and indirect effects included in the proposed model. Mothers’, but not fathers’, nativity was significantly associated with their endorsement of Mexican American cultural values and their ethnic socialization. Both mothers’ and fathers’ Mexican American cultural values were positively associated with their ethnic socialization. Mothers’ Mexican American values at the first assessment were not significantly correlated with their 10-year-olds Mexican American values at that assessment point, but they did significantly correlate with their children’s Mexican American values assessed two years later (and to changes in the adolescents values from Time 1 to Time 2). Mothers’ ethnic socialization was positively associated with adolescents’ ethnic identity; the association between fathers’ ethnic socialization and identity was in the same direction, but did not reach significance. Adolescents’ ethnic identity and cultural values at both time points were positively correlated. In addition, mothers’ and fathers’ nativity, Time 1 Mexican American cultural values, and Time 1 ethnic socialization were significantly correlated (r = .13, r = .21, and r = .23, all p < .001; respectively).

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for All Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | |||||||||

| 1. Nativity | |||||||||

| 2. T1 Mexican American Values | .11** | ||||||||

| 3. T1 Ethnic Socialization | .29*** | .35*** | |||||||

| Father | |||||||||

| 4. Nativity | .67*** | .06 | .28*** | ||||||

| 5. T1 Mexican American Values | .06 | .21*** | .10* | .07 | |||||

| 6. T1 Ethnic Socialization | .11* | .12** | .23*** | .06 | .30*** | ||||

| Adolescent | |||||||||

| 7. T1 Mexican American Values | −.04 | .02 | −.01 | .04 | .06 | −.03 | |||

| 8. T2 Ethnic Identity | .07† | .02 | .18*** | .11* | −.04 | .05 | .17*** | ||

| 9. T2 Mexican American Values | −.01 | .14*** | .04 | .00 | .06 | −.01 | .32*** | .42*** | |

|

| |||||||||

| Percent from Mexico | 74% | 80% | |||||||

| M | 4.40 | 3.1 | 4.37 | 3.0 | 4.51 | 4.02 | 4.36 | ||

| SD | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | ||

Note: T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Table 2.

Direct Effects and Indirect Effects for the Model of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Socialization of Their Young Adolescents’ Mexican American Values

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | Adolescent | |

| Parent | |||||||||

| 1. Nativity | |||||||||

| Direct Effect | .13** | .08 | |||||||

| Indirect Effects | .06† | .03 | .01* | .00 | .01* | .00 | |||

| 2. T1 Mexican American Values | |||||||||

| Direct Effect | .47*** | .36*** | |||||||

| Indirect Effects | .11*** | .00 | .05*** | .01 | |||||

| 3. T1 Ethnic Socialization | |||||||||

| Direct Effect | .23*** | .01 | |||||||

| Indirect Effects | .11*** | .00 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Adolescent | |||||||||

| 4. T1 Mexican American Values | |||||||||

| Direct Effect | .21*** | ||||||||

| Indirect Effects | |||||||||

| 5. T2 Ethnic Identity | |||||||||

| Direct Effect | .46*** | ||||||||

Notes: T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

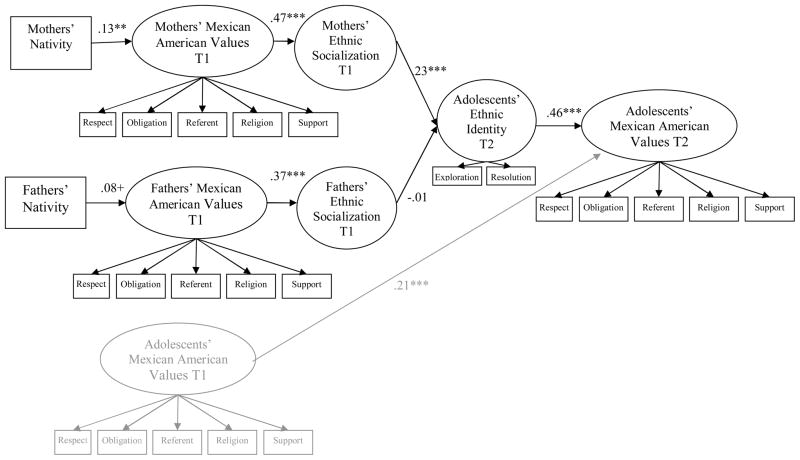

Test of the Hypothesized Model

To examine the pathways by which Mexican American cultural values may be transmitted to youth via ethnic socialization, we tested the model presented in Figure 1. The practical fit indices suggested good fit for the hypothesized model [χ2 (283) = 691.61, p ≤ .001; RMSEA = .04 (.04–.05); CFI = .93; SRMR = .05]. Mothers’ and fathers’ nativity (β = .16, p ≤ .001 and β = .09, p ≤ .08, respectively) were positively associated with their Mexican American values, which were in turn positively associated with their ethnic socialization practices (β = .47, p ≤ .001 and β = .36, p ≤ .001, respectively). Although mothers’ ethnic socialization was positively associated with adolescents’ ethnic identity across a two year time period (β = .22, p ≤ .001), fathers’ ethnic socialization was not associated with adolescents’ ethnic identity across this time period (β = .01, ns). In addition, adolescents’ ethnic identity was associated with an increase in Mexican American values over time (β = .48, p ≤ .001).

Figure 1.

The Model of the Generational Transmission of Mexican American Values in Mexican American Families.

Tests of Alternative Models

Interaction between mothers and fathers ethnic socialization

To determine if there was an interactive or joint influence of the ethnic socialization of mothers and fathers beyond their individual effects, we examined a model that added the interaction between the mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization. The inclusion of this interaction did not improve model fit [χ2 (306) = 747.65, p ≤ .001; RMSEA = .04 (.04–.05); CFI = .92; SRMR = .05], and the path coefficient for the interaction of mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization on adolescents’ ethnic identity was not significant (β = −.02).

Moderation by gender

To determine the degree to which the pathways in the hypothesized model were moderated by adolescents’ gender, a series of multi-group SEM models was examined. In these analyses, a first model constrained the path coefficients to be equal across gender groups and a second model allowed the path coefficients to vary across groups (i.e., was unconstrained). Model fit was deemed to be different across groups if the chi-square difference test between these nested models was significant, and if there were substantial differences in the practical fit indices (CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR) in the constrained and unconstrained models. If the model fit is significantly better for the unconstrained model compared to the constrained model then moderation exists. One can then examine the differences in the path coefficients across genders and also test partially constrained models to determine exactly which pathways are moderated by gender. The model constraining the path coefficients to be equal for girls and boys fit the data well [χ2 (610) = 1018.51, p ≤ .001; RMSEA = .04(.04–.05); CFI = .93; and SRMR = .08]. The unconstrained model, which allowed the path coefficients to differ for girls and boys also fit the data well [χ2 (606) = 1,013.19, p ≤ .001; RMSEA = .04(.04–.05); CFI = .93; and SRMR = .08]. In addition to the practical fit indices being comparable across these two models, the difference in χ2 across the constrained and unconstrained models was not significant [Δχ2 (Δdf=4) = 5.32, p = .26]. Hence, there was no youth gender difference in the fit of this socialization model.

Ethnic identity as a moderator

To determine whether adolescents’ ethnic identity functioned as a moderator, rather than a mediator, an alternative model that included direct pathways from mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization to adolescents’ Mexican American values at Time 2, with adolescents’ ethnic identity as a moderator of these pathways was examined. Although this model fit the data reasonably well [χ2 (376) = 848.89, p ≤ .001; RMSEA = .04 (.04–.05); CFI = .93; SRMR =.05], neither interaction path was significant (β = .03 and .01, for mothers’ and fathers’ respectively), nor were the direct paths from mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization to adolescents’ Mexican American values significant (β = .04 and −.05, for mothers’ and fathers’ respectively). Hence, this alternative model was less satisfactory.

Direction of adolescent ethnic identity and Mexican American values relation

To determine whether the direction of the relation between the adolescents’ ethnic identity and Mexican American values could be opposite than in the hypothesized model an alternate model switching the sequence of adolescents’ ethnic identity and adolescents’ Mexican American values was examined. Although this model fit the data reasonably well [χ2 (287) = 714.26, p ≤ .001; RMSEA = .05 (.04–.05); CFI = .93; SRMR = .05], neither of the direct pathways between the mothers’ or fathers’ ethnic socialization to the change in adolescents’ Mexican American values were significant (i.e., βs = .02 and −.06, for mothers’ and fathers’ respectively). Hence, this alternative model was less satisfactory.

Discussion

The present findings of the hypothesized and alternative models support the socialization model developed by Knight Bernal, Garza, and Cota (1993) and expanded by Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al. (2009) by indicating that: (a) mothers’ and (tentatively) fathers’ nativity was positively related to their Mexican American values, (b) mothers’ and fathers’ Mexican American values were positively related to the ethnic socialization experiences they provided for their early adolescent children, and (c) mothers’ reported ethnic socialization practices at the first assessment were positively related to adolescents’ ethnic identity and Mexican American values two years later (at approximately 12 years of age), and to their changes in their early adolescents Mexican American values over those two years. Not only are these findings consistent across boys and girls of Mexican descent, but the cross-reporter and longitudinal prospective nature of these analyses, as well as the reliance on a relatively diverse sample of Mexican American families, provides greater confidence in the proposition that Mexican American mothers’ culturally related values are being transmitted to their early adolescents. Hence, Mexican American adolescents’ ethnic identity development and internalization of Mexican American values are facilitated by mother-child interactions and the importance placed on Mexican American values through ethnic socialization. This evidence of the familial transmission of ethnic identity and culturally related values is particularly important given the evidence that a strong ethnic identity and culturally related values may have important and positive developmental outcomes (e.g., Berkel et al., 2010; Calderón-Tena et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2006; Huynh & Fuligni, 2008; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007).

Also noteworthy, is that the transmission of Mexican American values appears to be based more upon Mexican American mothers’ values and ethnic socialization efforts than Mexican American fathers’ values and ethnic socialization. Although fathers’ endorsement of Mexican American values was positively associated with their reported ethnic socialization, neither their values nor their socialization were substantially related to their adolescents’ ethnic identity or Mexican American values. These differences in the influence of mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization on their youths cultural orientation is consistent with the findings from several other studies of families from several ethnic/racial groups (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; McHale et al., 2006; Su & Costigan, 2009). There are a number of potential speculative reasons for differences between fathers’ and mothers’ roles in socializing their youths’ cultural orientation. Mothers may be more likely to be the primary socializing agents of their adolescents’ cultural orientation and have a more direct impact on their adolescent’s culturally related values. Particularly in relatively traditional Mexican American families, fathers may leave the direct socialization of values to the mother. It may also be that fathers’ ethnic socialization effects occur when their youths are at a different age or developmental state, or father’s ethnic socialization may occur though some other type of socialization experience other than talking with their youths about their culture. There is evidence, for example, that fathering roles in Latino families have traditionally included more of a focus on modeling and sanctioning than verbal parenting (Taylor & Behnke, 2005). Further examination of this issue would make a valuable contribution to our understanding of the familial transmission of cultural orientation.

The present model is based upon the hypothesis that some substantial commitment to, and understanding of, the Mexican American culture is to some extent a necessary precondition to the internalization of Mexican American values. Learning about Mexican American culture is essential in identifying the values associated with that culture, and a commitment to the Mexican American ethnic group is essential to having a positive vision of those values. Hence, as expected, ethnic identity (indexed by ethnic exploration and resolution) functioned as a mediator between the mother’s ethnic socialization and their youth’s Mexican American values. This is consistent with social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), self categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987), and the empirical evidence linking ethnic identity to cultural orientation (e.g., Armenta et al., 2010; Kiang & Fuligni, 2009; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009). Given that late childhood and early adolescence may be a prime developmental stage for the development of ethnic identity as well as the internalization of culturally related values, empirical investigation of the relations among these constructs may be very useful in furthering our understanding of the socialization of cultural orientations and the mental health outcomes associated with that socialization.

Interestingly, mothers’ Mexican American values at the first assessment were not concurrently related to their 10-year-olds Mexican American values, but they did significantly forecast children’s Mexican American values two years later, as well as changes in Mexican American values between 10- and 12-years-of-age. This may also have to do with the youths’ developmental readiness for the internalization of values. Internalization is the process whereby these values become a self chosen guide for behavior rather than guidance imposed by socialization agents. Younger children may behave in accordance with the cultural values of the parents and other socialization agents largely because of the sanctions, either positive or negative, associated with behaving accordingly. With repeated socialization experiences, and with advancing cognitive development, early adolescents’ acquire the capacity to abstract rules from these experiences and may begin to understand that their parents’ behavioral expectations have some common and more general threads that apply to a broader set of situations than those in which these socialization experiences are encountered. This abstraction and elaboration of rules may be the beginning of the creation of a value system. Indeed, there is evidence that late childhood or early adolescence is a time at which important changes in reasoning and values begin to emerge (e.g., Eisenberg, Miller, Shell, McNalley, & Shea, 1991).

There are a number of limitations in this research that are noteworthy. First, even though the theoretical model on which this research is based (Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004) and other socialization models (e.g., Arnett, 1995) described both familial and non-familial socialization influences including the broader cultural context, we focused only on the generational transmission of culturally related values from parents to their children. Although we believe that parents have the greatest impact on the generational transmission of cultural orientation, we also believe that other family members and a wide array of non-familial socialization agents in the living context may also be impactful. Second, we assessed a relatively narrow set of indicators of ethnic socialization by asking parents about the kinds of things they tell their early adolescent children rather than assessing broader ethnic socialization such as the specific behavioral sanctions they impose or the specific behaviors they model. The examination of these and other ways ethnic parents may engage in ethnic socialization is sorely needed. However, the type of verbal ethnic socialization examined in this study may be particularly important for the development of culturally related values because it may reduce the somewhat demanding cognitive load associated with the internalization of values. Perhaps the discussion mothers have with their early adolescent children supports the abstraction and elaboration of the rules that form the basis for any particular value. The types of verbal exchanges assessed in this measure of ethnic socialization may provide the context in which ethnic identity development advances, and may be necessary for the generational transmission of culturally related values. This is consistent with the significant longitudinal, but not concurrent, relations between mothers’ and adolescent’s Mexican American values at the first assessment and their early adolescents’ Mexican American values; as well as much of the literature on racial socialization that focuses on how parents talk with their children about prejudice and discrimination and the impact of these discussions on preparation for racial bias, self esteem maintenance, and racial identity (e.g., Hughes et al., 2006). Third, ethnic identity was assessed at only one point in time which limits our ability to address the causal direction issue. However, evidence from earlier research (Kiang & Fuligni, 2009) and the alternative models tested herein strongly suggests that the development of ethnic identity is a precursor to the internalization of culturally related values.

Even given these limitations, the present research makes several important contributions to the literature. First, although portions of the model of the generational transmission of culturally related values and cultural orientation have been examined in the literature, to our knowledge this is perhaps the only empirical assessment of the entire process. Furthermore, our tests of hypothesized and alternative models provide support for the thesis that maternal values are transmitted to children through an active and developmental process. Specifically, at the transition to adolescence, parents’ values are associated with their ethnic socialization practices, which support youths’ development of Mexican American identities, which in turn lead to the internalization of cultural values. Second, although ethnic socialization has been related to adolescents’ ethnic identity and cultural orientation (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009), the existing literature has generally relied upon data from a single reporter (usually the adolescent, and rarely included the fathers’ self reports), allowing the possibility of a relation between ethnic socialization and ethnic identity because of common reporter effects. Third, even though bidirectional effect cannot be examined in this study the longitudinal nature and the prospective analyses allow greater confidence in the hypothesized causal pathways, especially in contrast to the alternative models, relative to previous research. Finally, these findings provide strong support for the notion that the development of ethnic identity mediates the association between mothers’ ethnic socialization and adolescents’ Mexican American values.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by NIMH grant MH68920 (Culture, Context, and Mexican American Mental Health) and the NIMH Training Grant T32MH18387. The authors are thankful for the support of Mark Roosa, Jenn-Yun Tein, Marisela Torres, Jaimee Virgo, our Community Advisory Board and interviewers, and the families who participated in the study.

References

- Armenta BE, Knight GP, Carlo G, Jacobson RP. The relation between ethnic group attachment and prosocial tendencies: The mediating role of cultural values. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;40:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Broad and narrow socialization: The family in the context of a cultural theory. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1995;57:617–628. [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein JY, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, Saenz D. Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Tanner-Smith EE, Lesane-Brown CL, Ezell ME. Child, parent, and situational correlates of familial ethnic/race socialization. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Tena CO, Knight GP, Carlo G. The socialization of prosocial behavior tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: The role of familism values. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:98–106. doi: 10.1037/a0021825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Miller PA, Shell R, McNalley S, Shea C. Prosocial development in adolescence: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:849–857. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Witkow M, Garcia C. Ethnic identity and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:799–811. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Fabrett FC, Knight GP. Acculturation, enculturation and the psychosocial adaptation of Latino youth. In: Villaruel FA, Carlo G, Grau J, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook of US Latino Psychology: Developmental and Community-Based Perspectives. Sage Publications; 2009. pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic socialization and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(4):1202–1208. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic identity and family processes among adolescents from Latin American, Asian and European backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:228–241. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal MB, Garza CA, Cota MK, Ocampo KA. Family socialization and the ethnic identity of Mexican American children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1993;24:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal ME, Garza CA, Cota MK. A social cognitive model of ethnic identity and ethnically-based behaviors. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Cota MK, Bernal ME. The socialization of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic preferences among Mexican American children: The mediating role of ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1993;15:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds D, German M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim J, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, et al. Mothers' and fathers' racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development. 2006;77:1387–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user's guide (Version 5.1) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Lee S. Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:311–342. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity is adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Liu F, Torres M, Gonzales N, Knight G, Saenz D. Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su TF, Costigan CL. The development of children’s ethnic identity in immigrant Chinese families in Canada: The role of parenting practices and children’s perceptions of parental family obligation expectations. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:638–663. [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, Behnke A. Fathering across the border: Latino fathers in Mexico and the U.S. Fathering. 2005;3:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, Guimond AB. The central role of family socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Examining ethnic identity among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:36–59. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Guimond AB. Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development. 2009;80:391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents' mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(4):549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Knight GP, Zeiders KH. Language measurement equivalence of the Ethnic Identity Scale with Mexican American early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. doi: 10.1177/0272431610376246. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]