Abstract

This work illustrates a simple approach for optimizing the lanthanide luminescence in molecular dinuclear lanthanide complexes and identifies a particular multidentate europium complex as the best candidate for further incorporation into polymeric materials. The central phenyl ring in the bis-tridentate model ligands L3–L5, which are substituted with neutral (X = H, L3), electronwithdrawing (X = F, L4), or electron-donating (X = OCH3, L5) groups, separate the 2,6-bis(benzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine binding units of linear oligomeric multi-tridentate ligand strands that are designed for the complexation of luminescent trivalent lanthanides, Ln(III). Reactions of L3–L5 with [Ln(hfac)3(diglyme)] (hfac− is the hexafluoroacetylacetonate anion) produce saturated single-stranded dumbbell-shaped complexes [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5), in which the lanthanide ions of the two nine-coordinate neutral [N3Ln(hfac)3] units are separated by 12–14 Å. The thermodynamic affinities of [Ln(hfac)3] for the tridentate binding sites in L3–L5 are average , but still result in 15–30% dissociation at millimolar concentrations in acetonitrile. In addition to the empirical solubility trend found in organic solvents (L4 > L3 ≫ L5), which suggests that the 1,4-difluorophenyl spacer in L4 is preferable, we have developed a novel tool for deciphering the photophysical sensitization processes operating in [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6]. A simple interpretation of the complete set of rate constants characterizing the energy migration mechanisms provides straightforward objective criteria for the selection of [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6] as the most promising building block.

Introduction

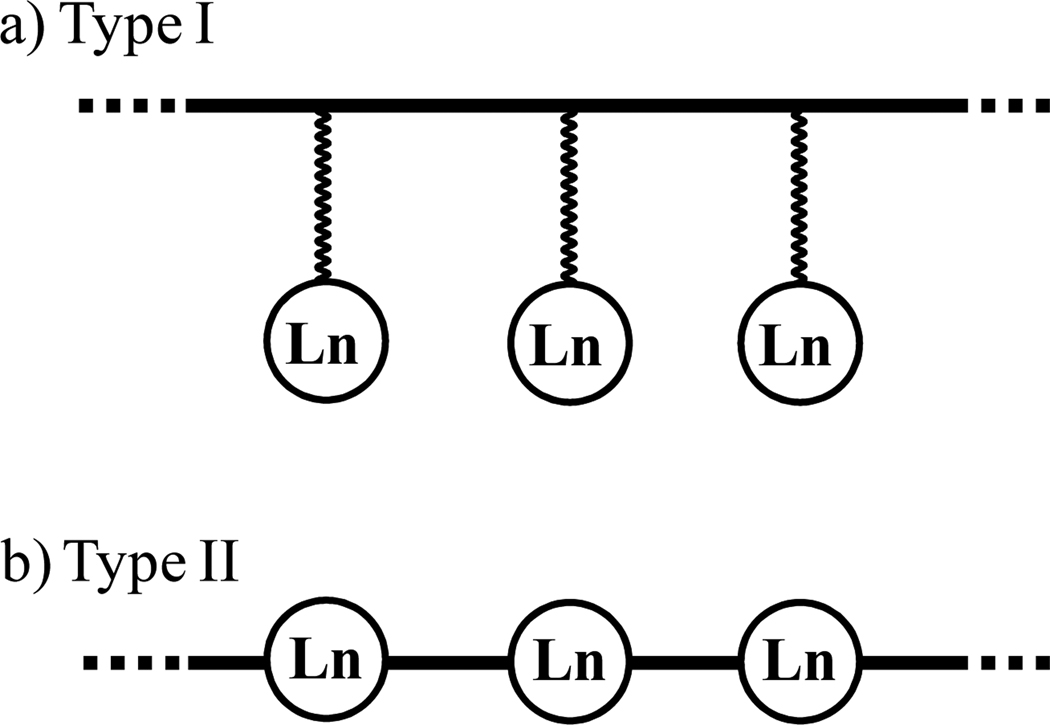

Beyond the now routine dispersion of luminescent trivalent lanthanides, Ln(III), into coordination polymers or hybrid materials for the production of improved dyes for organic light-emitting diodes (OLED) or lighting devices,1,2 an emerging strategy is to exploit well-identified organic polymeric scaffolds for the selective sequestration of luminescent trivalent lanthanides.3,4 In this context, specific binding sites coded for trivalent lanthanides, such as 2,2’;6’,2” terpyridine,3a,3b,3f 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA),3c diethylenetriamine-pentaacetic acid (DTPA)3d or propionic acid,3e are connected to the backbone of pre-formed polymers via flexible alkyl linkers (Fig. 1a, Type I). However, the final distribution of bound metal ions has evaded satisfactory supramolecular control.3 Alternatively, didentate 1,10-phenanthroline4a or tridentate 2,6-bis(2-thienyl)pyridine4b chelates can be incorporated within the backbone of the organic polymers with the aim of improving structural control over metal ion placement upon complexation (Fig 1b, Type II).

Figure 1.

The figure shows two different strategies for the introduction of lanthanide-binding sites into organic polymers. The chelating units are a) connected to the periphery (Type I)3f or b) incorporated within the polymer backbone (Type II).4

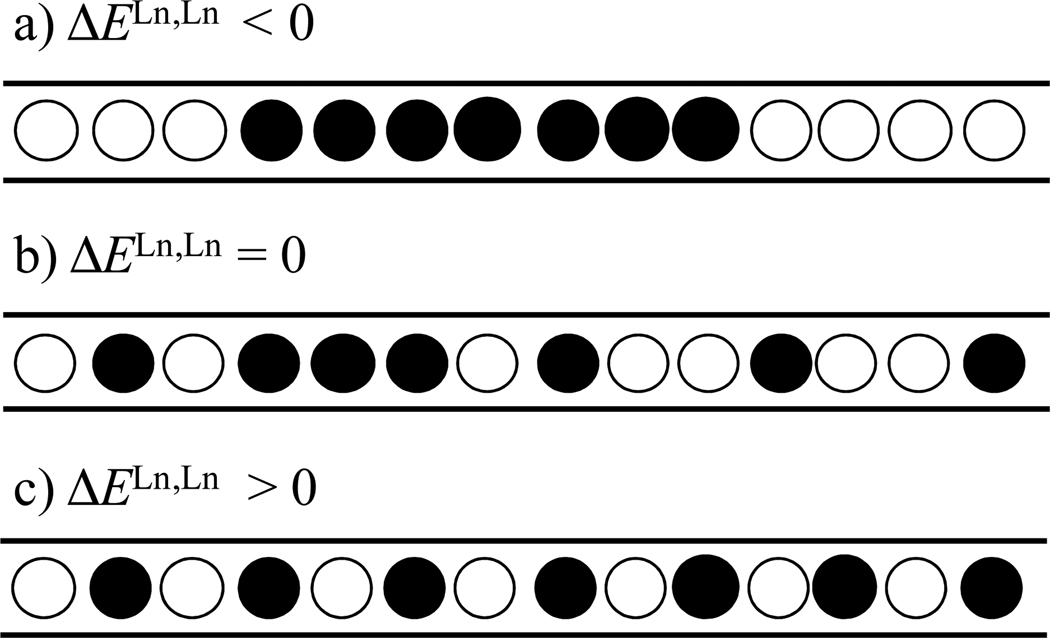

Alhough the structural and thermodynamic data reported for metal loading in these Type II polymers are still scarce,4 Borkovec and coworkers theoretically predicted that, depending on the sign of the pair interaction energy ΔELn,Ln between two occupied adjacent sites, such linear receptors can be intentionally half-filled with lanthanide cations in order to obtain either metal ion clustering (ΔELn,Ln < 0, Fig 2a), a statistical distribution (ΔELn,Ln ≈ 0, Fig. 2b), or metal ion alternation (ΔELn,Ln > 0, Fig 2c) in the binding sites.5 Interestingly, similar behavior is predicted for the saturation of these polymers with two different competitive lanthanide metals Ln1(50%) and Ln2(50%), if ΔELn,Ln is replaced with the effective pair interaction energy ΔEeff = ΔELn1,Ln1 + ΔELn2,Ln2 − 2ΔELn1,Ln2.5 Such unprecedented lanthanide discrimination offers great potential for the design of functional optoelectronic devices that require specific sequences of different metals, for instance in the field of optical downconversion,6 upconversion,7 dual analytic probes,8 and four-level lasers.9 However, the manipulation of ΔELn,Ln in solution is challenging because the net interaction energy arises from a delicate balance between the intramolecular electrostatic repulsions of the metal ions and the opposing stabilizing solvation energies; in addition, both of these contributions are highly sensitive to geometrical parameters.6

Figure 2.

The diagram shows a representation of microstates of half-occupied polymeric linear receptors displaying a) attractive, b) negligible, and c) repulsive nearest-neighbor pair interaction energies.5

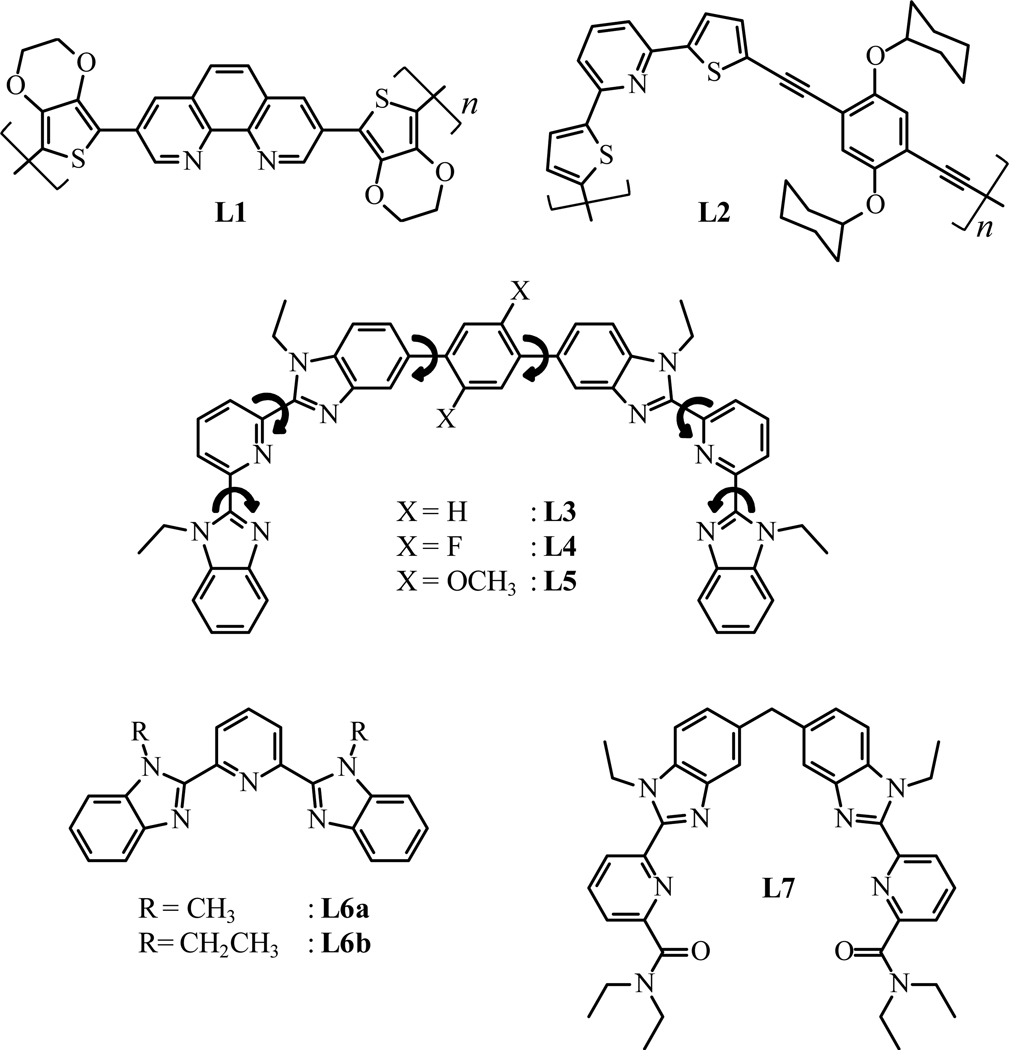

The state-of-the-art for rational control over ΔELn,Ln is only compatible with the production of rigid linear receptors that possess regularly spaced binding sites, as schematically depicted in Fig. 2.10 The quantification of the geometrical arrangement and thermodynamic parameters of the final metal-loaded polymers would greatly benefit from the use of metal cations that can also function as efficient luminescent reporters.11 Thus, semi-rigid polyaromatic tridentate binding units coded for luminescent cations and separated by rigid aromatic spacers are a promising tool for addressing this challenge. This conclusion was already reached by (i) Holliday and coworkers who took advantage of the electro-polymerization of thienyl spacers in L1 followed by reaction with luminescent Eu(β-diketonate)3,4a and by (ii) Bai and coworkers who used Sonogashira coupling reactions for connecting tridentate binding units with diacetylene-phenyl spacers in L2 (Scheme 1). Inspired by these pioneering efforts, we used a Suzuki-Miyaura protocol for coupling two tridentate 2,6-bis(benzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine binding units at the 1,4 positions of the rigid phenyl spacer in L3.12 Because of the restricted number of torsional degrees of freedom imposed by the polyaromatic scaffold (n = 6 inter-annular free rotations, Scheme 1), the reaction of L3 with trivalent lanthanides in acetonitrile shows the formation of the target linear complex [Ln2(L3)]6+ and a side product of [Ln2(L3)2]6+, instead of the usual saturated polycyclic triple-stranded helicates.13 Pushing further this advantage, we replaced the original Ln(O3SCF3)3 salts with poorly dissociable Ln(hfac)3 metallic units (hfac− is the didentate hexafluoroacetylacetonate anion)1 for ensuring the formation of the saturated single-stranded complex [Ln2(L3)(hfac)6] as the only stable product of the assembly process. Concomitantly, we exploited this synthetic effort for the development of a simple and general tool (i) for the deciphering of ligand-centered sensitization in luminescent lanthanide-containing polyaromatic complexes14 and (ii) for the optimization of luminescence efficiency in [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5) via specific substitutions of the central phenyl spacers with neutral (X = H, L3), electron-withdrawing (X = F, L4), or electron-donating (X = OCH3, L5) groups.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures are shown for ligands L1–L7.

Results and discussion

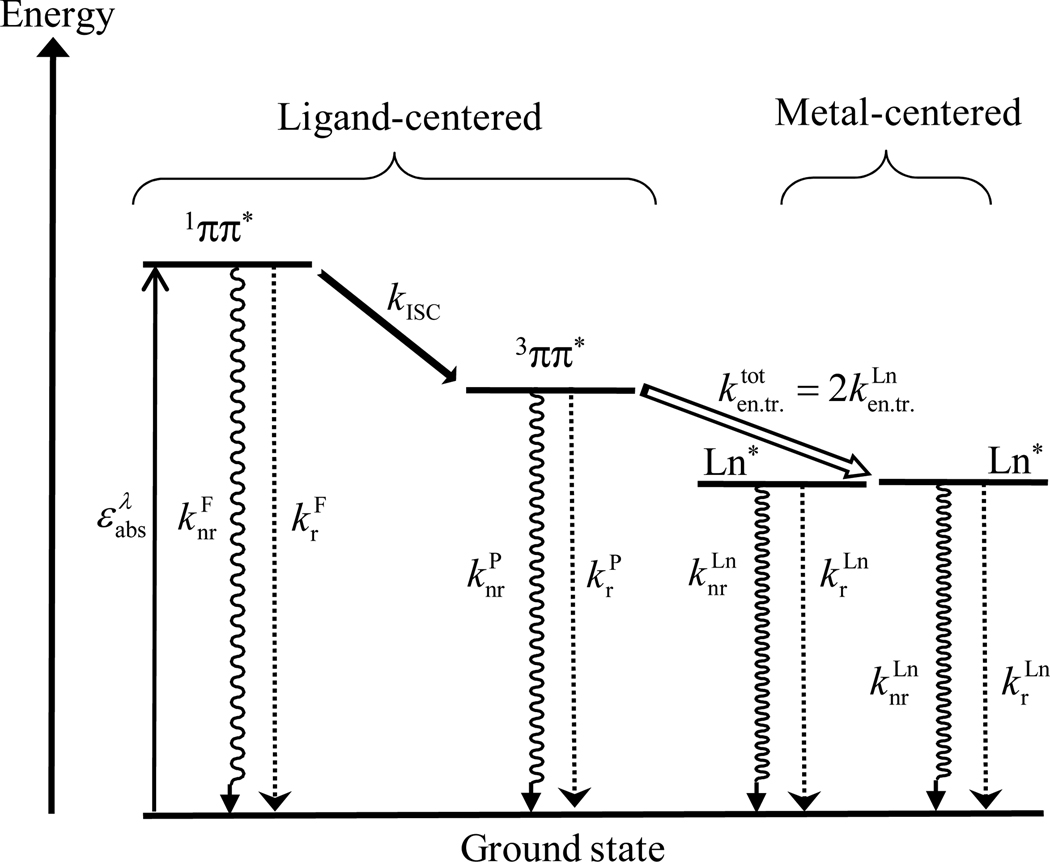

Theoretical justifications for the design of ligands L3–L5

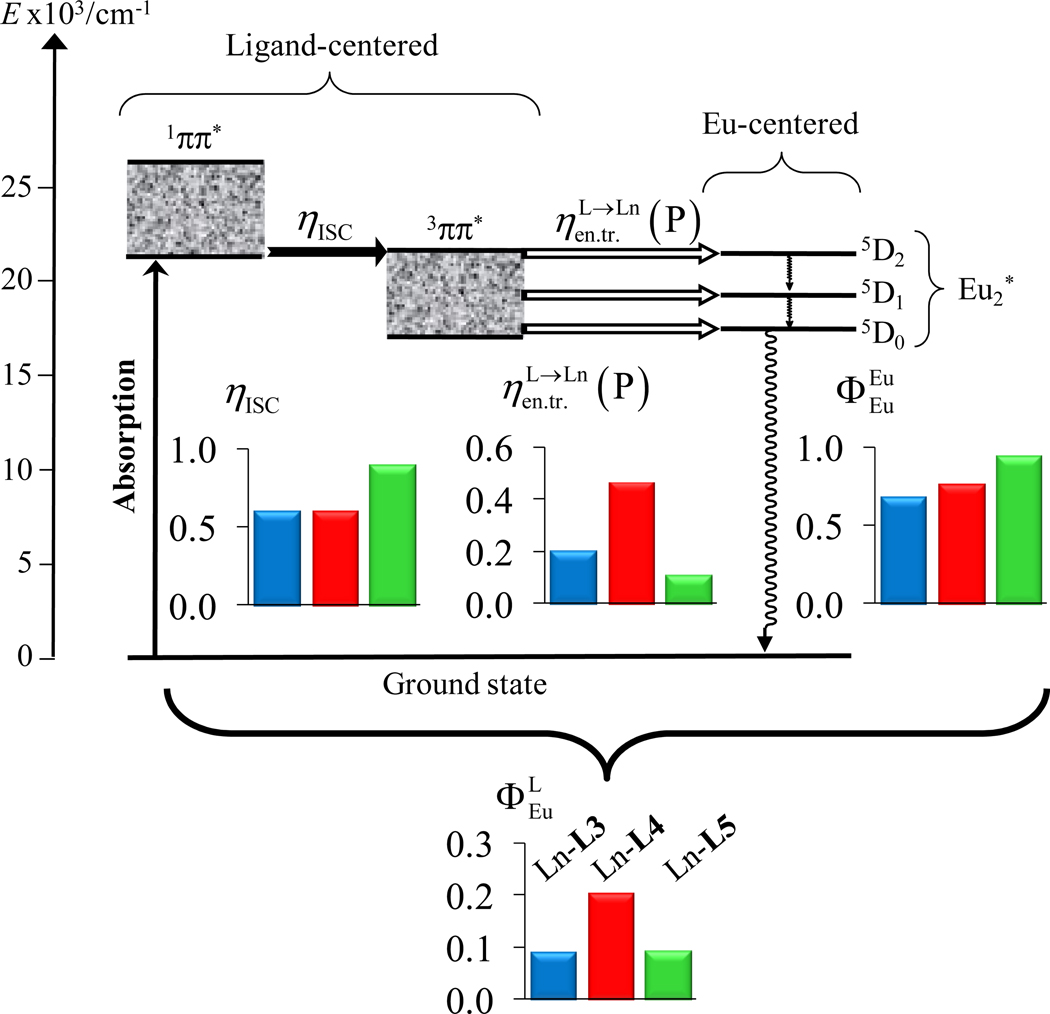

Beyond empirical solubility considerations, the benefit of a substituted phenyl spacer in the ligands L3–L5 strongly depends on the substituent’s influence on the photophysics of the final complexes [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6]. Since the discovery of the concept of indirect ligand-centered sensitization of lanthanide cations, i.e. the antenna effect, by Weissman in 1942,15 pertinent energy migration mechanisms have been described and detailed in many reports.14,16,17 For Eu(III), the accepted model relies on a resonant or phonon-assisted feeding of metal-centred excited states from ligand-centered excited 1ππ* or 3ππ* levels when their characteristic lifetimes are long enough to significantly contribute to the global energy transfer.17 Given the experimental ligand-centered fluorescence lifetimes of only 30–70 ps that are measured for the [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] (Lk = L3–L5, Table 2, vide infra) complexes, it appears likely that the energy migration processes in [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] can be satisfyingly modeled with the exclusive contribution of the triplet state as shown in Fig. 3.14,16 With this hypothesis in mind, it is worth noting that the rate equations 1–5 describe the efficiency of the indirect ligand-centered sensitization of Ln(III). In these equations, are the intrinsic ligand-centered quantum yields of fluorescence (F) and phosphorescence (P), respectively; is the intrinsic metal-centered quantum yield of luminescence;18 are the efficiencies of intersystem crossing and ligand-to-metal energy transfer processes, respectively;19 and τL (F) and τL (P) are the characteristic excited-state lifetimes of ligand-centered fluorescence (F) and phosphorescence (P). τLn is the excited-state lifetime of the metal-centered luminescence. The definition of each individual rate constant is given in the caption of Fig. 3.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Table 2.

Fluorescence Quantum Yields and Lifetimes (τL(F)), Computed Rate Constants and π-Conjugation Lengths (Aπ) for L3–L6 and for their Complexes [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] at 293K.

| Compound | Conc./ M | ν̄exc /cm−1 | ε(ν̄exc) /M−1cm−1 |

τL(F)/ ns |

kISC /ns−1a |

ηISCa |

|

Aπ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution (CH2Cl2) | |||||||||||||||

| QSO4c | 6.42·10−6 | 27780 | 8100 | 0.546 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.18 | ||||

| L3 | 10−5 | 27780 | 4000 | 0.80(8) | 2.04(7) | 0.39(4) | 0.10(7) | - | - | - | 1.39(6) | ||||

| L4 | 10−5 | 27780 | 4300 | 0.74(8) | 1.374(4) | 0.54(6) | 0.17(2) | - | - | - | 1.05(7) | ||||

| L5 | 10−5 | 27780 | 3300 | 0.40(5) | 2.37(18) | 0.19(10) | 0.25(4) | - | - | - | −0.41(8) | ||||

| L6ad | 9.86·10−5 | 28820 | 5130 | 1.00(7) | 1.9(1) | 0.53(5) | 0.00(6) | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Solid state | |||||||||||||||

| L3 | - | 29550 | - | 0.045(2) | 0.149(12) | 0.30(3) | 6.41(4) | - | - | - | −3.05(3) | ||||

| L4 | - | 29550 | - | 0.049(2) | 0.160(3) | 0.31(1) | 5.94(2) | - | - | - | −2.97(3) | ||||

| L5 | - | 29550 | - | 0.023(1) | 0.221(7) | 0.104(6) | 4.421(9) | - | - | - | −3.75(3) | ||||

| [Gd2(L3)(hfac)6] | - | 29850 | - | 0.00316(7) | 0.060(2) | 0.053(2) | 16.6(7) | 10.0(6) | 0.60(3) | 6.7(8) | −4.84(5) | ||||

| [Gd2(L4)(hfac)6] | - | 29850 | - | 0.0035(5) | 0.066(14) | 0.05(1) | 15(4) | 9(2) | 0.6(1) | 6(4) | −4.8(3) | ||||

| [Gd2(L5)(hfac)6] | - | 29850 | - | 0.0027(10) | 0.028(16) | 0.09(7) | 36(24) | 31(18) | 0.9(5) | 4(27) | −3.8(2.7) |

Figure 3.

This simplified Jablonski diagram for [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5) shows the ligand-centered triplet-mediated sensitization mechanism of the two trivalent lanthanides.20 , kISC = intersystem crossing rate constant, and .19

The overall luminescence intensity (eq 6)14a,21 expressed in M−1·cm−1, combines the contribution of the light-harvesting step (measured by the molar absorption coefficients of the ligand-centered 1ππ→1ππ* transition) with that of the global quantum yield characterizing the complete energy migration scheme (eq 7).14

| (6) |

| (7) |

The intrinsic lanthanide quantum yield (eq 3) has been the subject of considerable investigations,18a,22 and its rationalization in coordination complexes relies on the Judd-Ofelt theory which considers odd-rank crystal-field contributions as the origin of the non-negligible radiative rate ,23 while vibrationally-coupled deactivation pathways control .24 These parameters are not particularly sensitive to substituents on the phenyl spacer in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5), and thus is not expected to vary significantly in these complexes. The next important contribution to the overall emission yield is the efficiency of the ligand-to-metal energy transfer (eq 5), which has undergone intense investigations during the last decades, also.11,14,16,24,25 Assuming the exclusive contribution of the triplet mechanism for Eu sensitization, a good match between the energy of the donor ligand-centered 3ππ* excited state and the accepting Eu(III) excited levels is a prerequisite for optimizing .26 Because the energy of the ligand-centered triplet-state may be influenced by the substituents on the central phenyl ring in L3–L5, this factor should be considered in the ligand design. Surprisingly, the parameters influencing ηISC (eq 4) in lanthanide complexes have been rarely studied in detail or systematically optimized, except for (i) the elucidation of the origin of the favorable heavy atom and paramagnetic effects produced by the coordination of open-shell Ln(III) to aromatic ligands,27 and (ii) the intrinsic advantage of using fused polyaromatic scaffolds as antennae for sensitizing Eu and Tb.28 Eq 4 suggests that ηISC may be further optimized when the sum of the rate constants is negligible with respect to kISC . Following Yamaguchi and coworkers, the rate constants in polyaromatic systems correlate with the so-called π-conjugation length Aπ(no unit), which is proportional to the charge displacement that is induced in the excited state by the 1ππ→1ππ* transition of the organic scaffold.29

| (8) |

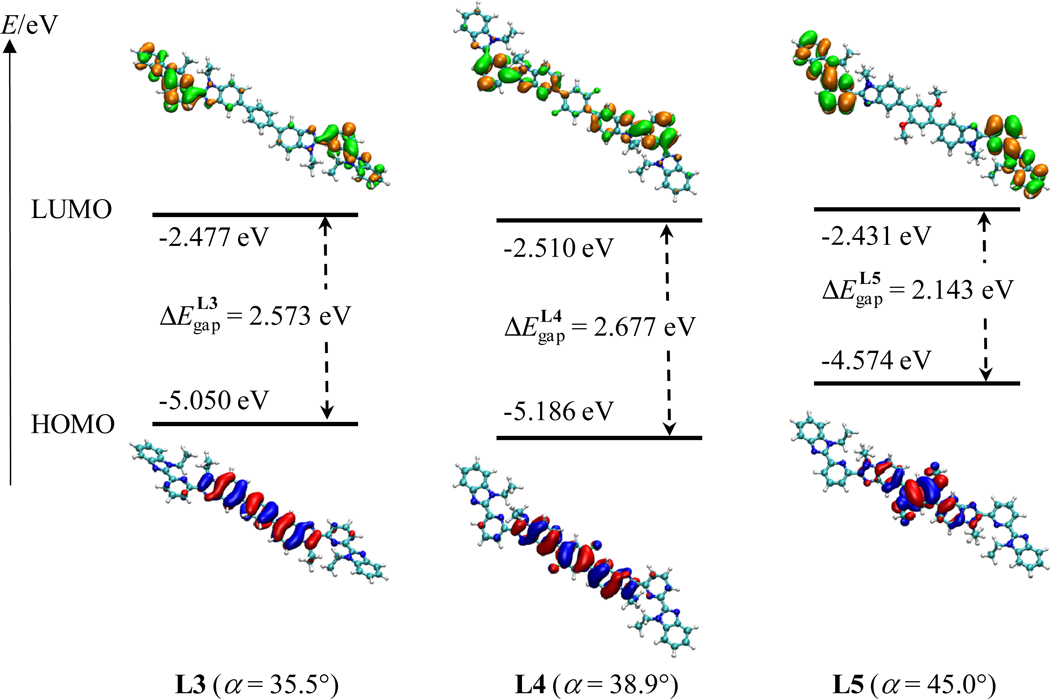

We immediately deduce from eq 8 that is a minimal value when both and Aπ are minimum. A significant tuning of is not expected for minor changes in the substitution of the central phenyl ring in L3–L5. However, Aπ could be seriously affected if the relevant low-energy 1ππ→1ππ* transition possesses charge transfer character involving the phenyl spacer. In order to address this specific point, DFT calculations were performed on the non-complexed ligand strands. First, we note that the computationally optimized gas-phase centrosymmetrical structures are very similar for the three ligands L3–L5, except for a small stepwise increase of the inter-annular torsion angles between the central 1,4-disubstituted phenyl spacer and the adjacent 5-benzimidazole rings (α(L3) = 35.5° 30 < α(L4) = 38.9° < α(L5) = 45.0°, Fig. 4 and Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information). Second, the calculated frontier orbitals show the HOMOs to be located on the central bis(benzimidazole)phenyl spacer and the LUMOs to lie on the terminal benzimidazole-pyridine rings of each binding unit (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The frontier orbitals, computed by DFT, are shown for L3–L5 in their optimized gas-phase geometries (1 eV = 8065.5 cm−1)

Thus, the substitution of the central phenyl rings mainly affects the energy of the HOMO, while that of the LUMO is only marginally affected. Consequently, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap increases as the electron-withdrawing capacity of the substituent increases; i.e., . Taking the trend in the HOMO→LUMO transition as a guide for how the π-conjugation length changes, we conclude that the variable charge-transfer character of this transition in L3–L5 may significantly affect this parameter. Thus, L3–L5 are good candidates for simultaneously optimizing solubilities and ligand-centered photophysical properties, while minimizing structural variations and synthetic efforts, and preserving metal-centered photophysical properties.

Synthesis, structures and photophysical properties of the bis-tridentate ligands L3–L5

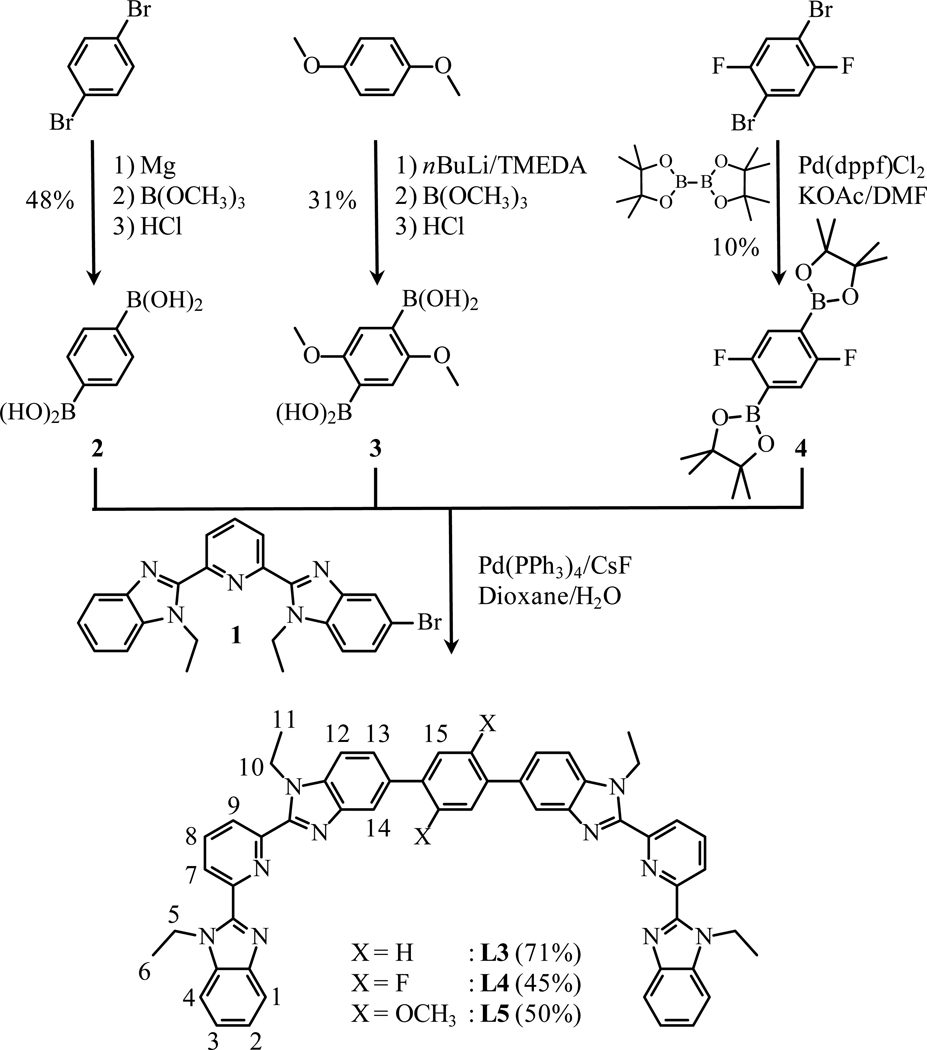

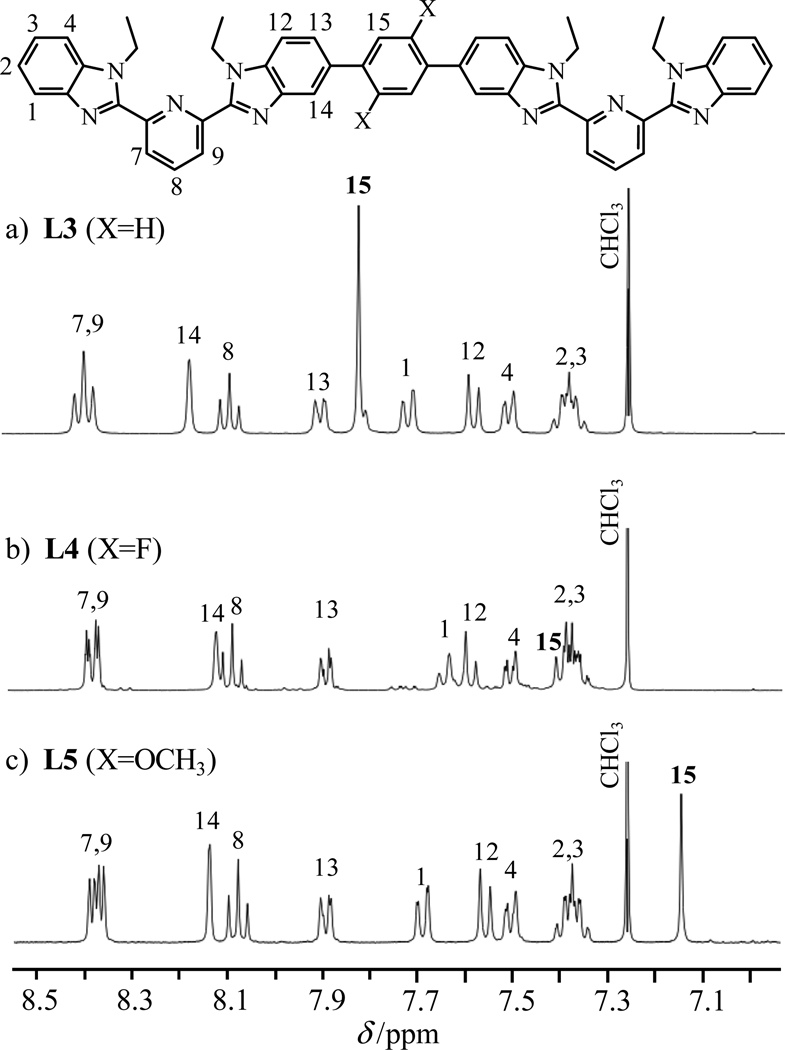

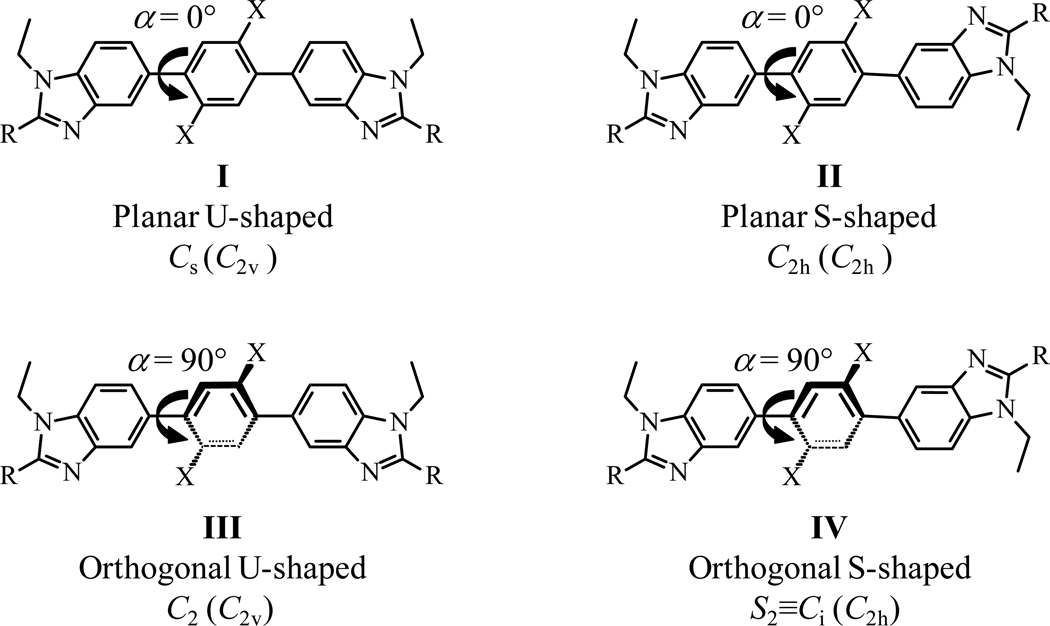

The formation of two Carom-Carom bonds are obtained via a Miyaura-Suzuki strategy12 using the mono-brominated compound 1 (Scheme S1, appendix 4). Reactions of the bis-boronic acids 2 and 3,31 or the bis-boronic ester 432 (1 eq) with 1 (2 eq) using standard Pd(0) catalyzed conditions12 provide L3–L5 in acceptable yields (Scheme 2). Because of the existence of an average twofold symmetry axis in solution (C2 or S2=Ci, Fig. 5 and Table S1), the 1H NMR spectrum of each ligand exhibits fifteen signals (Fig. S2); this pattern disqualifies arrangement I among the four static limiting structures shown in Scheme 3. The systematic detection of enantiotopic pairs for the methylene protons H5 and H10 (numbering in Scheme 2 and Fig. S2) discards structures III and IV because of the lack of the required additional symmetry plane for X = F, OCH3. Ligands L3–L5 thus adopt the average planar S-shaped arrangement II in chloroform, in agreement with the optimized DFT organization computed in the gas-phase.

Scheme 2.

The synthesis scheme and numbering scheme for 1H NMR of the ligands L3–L5 is shown here.

Figure 5.

Aromatic parts of the 1H spectra of L3–L5 in CDCl3 at 293 K are shown.

Scheme 3.

Possible static geometries are shown for the central bis(benzimidazole)phenyl spacer for ligands L3–L5 in solution (point groups are given for X ≠ H, while the related point groups for X = H are given in parentheses).

Interestingly, the singlet observed for H15 is the only 1H NMR signal sensitive to the nature of the substituent for L3–L5 (Fig. 5).33 This observation implies a limited conjugation of the central aromatic core in solution, which can be tentatively assigned to fast rotations and/or oscillations of the central substituted phenyl spacers on the NMR time scale at room temperature, an interpretation in complete agreement with the small activation energies reported for inter-aromatic rotations occurring in closely related diethyl-substituted terphenyl.34

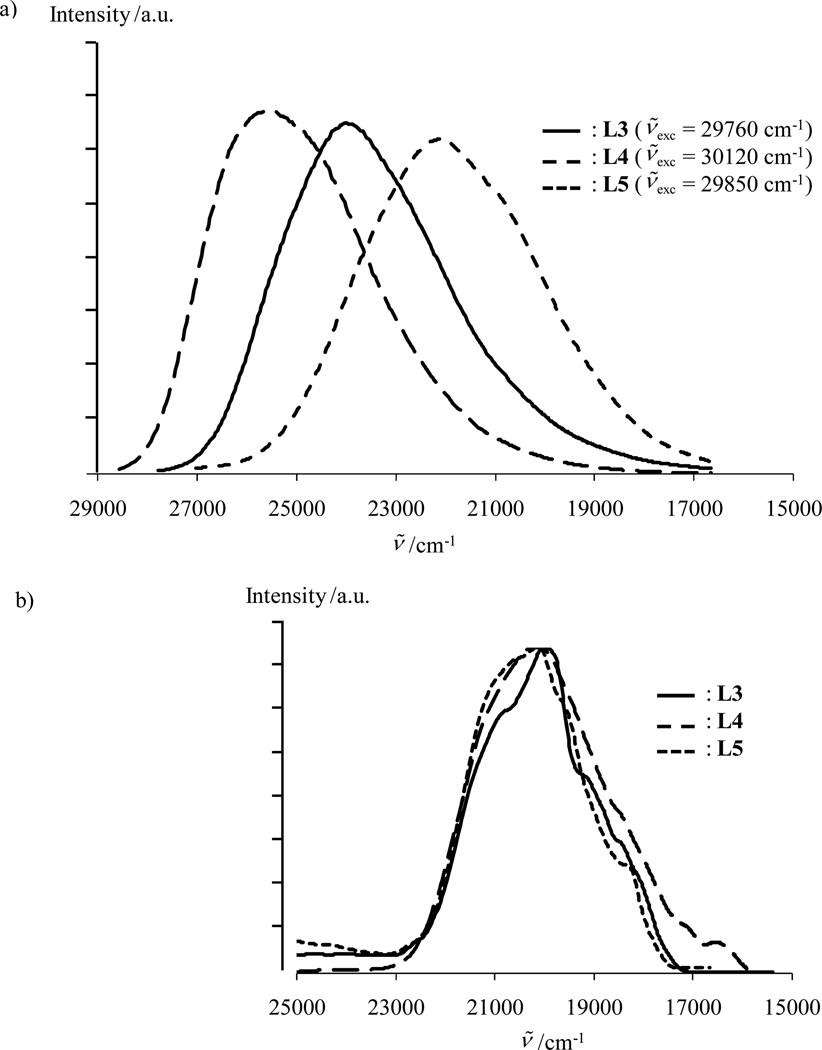

The electronic absorption spectra recorded in dichloromethane are similar for L3–L5 and show a broad and intense spin-allowed low-energy π→π* transition centered around 30000 cm−1 (Table 1 and Fig. S3). The decreasing energy order L4 > L3 > L5 found for the latter transition is also apparent in their associated emission spectra, in which the emission maxima follow the trend 25400 cm−1 (L4) > 23900 cm−1 (L3) > 22270 cm−1 (L5). These observations are in qualitative agreement with DFT calculations (Fig. 6a and Table 1). The same trend is retained in frozen solution at 77 K (Fig. S4), however the emission band envelopes shift slightly because of the thermal redistribution of the vibrational level populations and the possible blocking of the internal inter-annular rotations at low temperature (Fig. S5).34 Surprisingly, the position of the weak, but reliable, emission of the ligand-centered triplet states are not sensitive to the substitution of the phenyl spacer, and an average value of 20200 cm−1 can be assigned to all Lk(3ππ*) excited states at 77K (Table 1, Fig. 6b).

Table 1.

Ligand-centered Absorption and Emission Properties of L3–L6 and of their Complexes [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6].

| Compound | T /K | λmax,abs /cm−1a 1ππ→1ππ* |

λmax,flu /cm−1 1ππ*→1ππ |

Lifetime /ns τ (1ππ*) |

λmax,phos /cm−1 3ππ* |

Lifetime /ms τ (3ππ*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution (CH2Cl2) | ||||||

| L3 | 293 | 34250(57000) | 23900 | 2.04(7) | - | - |

| 77 | 29850(69500) | 24650 | - | 20200 | b | |

| L4 | 293 | 37480(43400) | 25400 | 1.374(4) | - | - |

| 77 | 29860(73300) | 25500 | - | 20240 | b | |

| L5 | 293 | 36850(50320) | 22200 | 2.37(18) | - | - |

| 77 | 29590(73300) | 24300 | - | 20200 | b | |

| L6a c | 293 | 41360(16000) | 27100 | 1.9(1) | - | - |

| 77 | 30980(35000) | 26400 | - | 22000 | b | |

| Solid state | ||||||

| L3 | 293 | 29850 | 23350 | 0.149(12) | - | - |

| 77 | - | 23310 | - | 18720 | b | |

| L4 | 293 | 29660 | 24180 | 0.160(3) | - | - |

| 77 | - | 25250 | - | 19480 | b | |

| L5 | 293 | 29590 | 24540 | 0.221(7) | - | - |

| 77 | - | 24600 | - | 19470 | b | |

| [Gd2(L3)(hfac)6] | 293 | 28650 | 22620 | 0.060(2) | 19070 | 0.123(7) |

| 77 | - | 22600 | 19070 | 0.69(5) | ||

| [Gd2(L4)(hfac)6] | 293 | 28650 | 23820 | 0.066(14) | 19470 | 0.16(2) |

| 77 | - | 22700 | - | 19470 | 0.67(5) | |

| [Gd2(L5)(hfac)6] | 293 | 28730 | 23780 | 0.028(16) | 19100 | 0.141(6) |

| 77 | - | 22100 | - | 19100 | 0.69(5) |

The molar absorption coefficients ε are given between parentheses in M−1·cm−1

The intensity is too weak to obtain reliable lifetime measurements.

Taken from ref. 21 and recorded in CH3CN.

Figure 6.

a) Fluorescence (293 K) and b) phosphorescence (delay time after excitation flash 0.1 ms, 77 K) emission spectra are shown for L3–L5 in solution (10−4 M in CH2Cl2).

The absolute quantum yields of fluorescence of L3–L5 in solution are considerable ( , see Table 2, column 5), and their combination with the Lk(1ππ*) fluorescence lifetimes (τL (F), Table 2, column 6), via eq 1 gives radiative fluorescence rate constants that follow a trend consistent with Einstein equation for spontaneous emission (L4 > L3 > L5, Table 2 column 7).35 The sum of the non-radiative rate constants remain similar for the three ligands within experimental errors (Table 2, column 8). Following Yamaguchi and coworkers who reasonably assume that for free polyaromatic ligands,29 eq 8 provide π-conjugation lengths of −0.4 ≤ Aπ≤ 1.4 for L3–L5 in solution (Table 2, column 12), which make these centrosymmetrical bis-tridentate polyaromatic ligands comparable to triphenylene (Aπ= −0.04) and tetraphenylene (Aπ= 1.82).29 A comparison of the photophysical and spectral properties of L3–L5 with that of the precursor ligand L6a, shows that the connection of two tridentate bis(benzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine units via substituted aromatic phenyl spacers in L3–L5 has two major consequences. First, both electronic absorption (1ππ→1ππ*, Fig. S3) and emission (1ππ*→1ππ and 3ππ*→1ππ) transitions of L3 to L5 are red-shifted by 1800–4800 cm−1 (Table 1). Second, novel non-radiative deactivation pathways are present for L3 to L5, and they limit the fluorescence quantum yields (Table 2). Note that upon crystallization, the fluorescence quantum yields and fluorescence lifetimes τL (F) concomitantly decrease by more than one order of magnitude (Table 2, columns 5 and 6), while the calculated radiative rate constant (eq 1) remains constant (Table 2, column 7). This observation indicates that the non-radiative rate constants are magnified by the additional intermolecular interactions in the solid state (Table 2, column 8).

Synthesis, structures and stabilities of the dinuclear complexes [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] (Ln = Gd, Eu, Y and Lk = L3–L5)

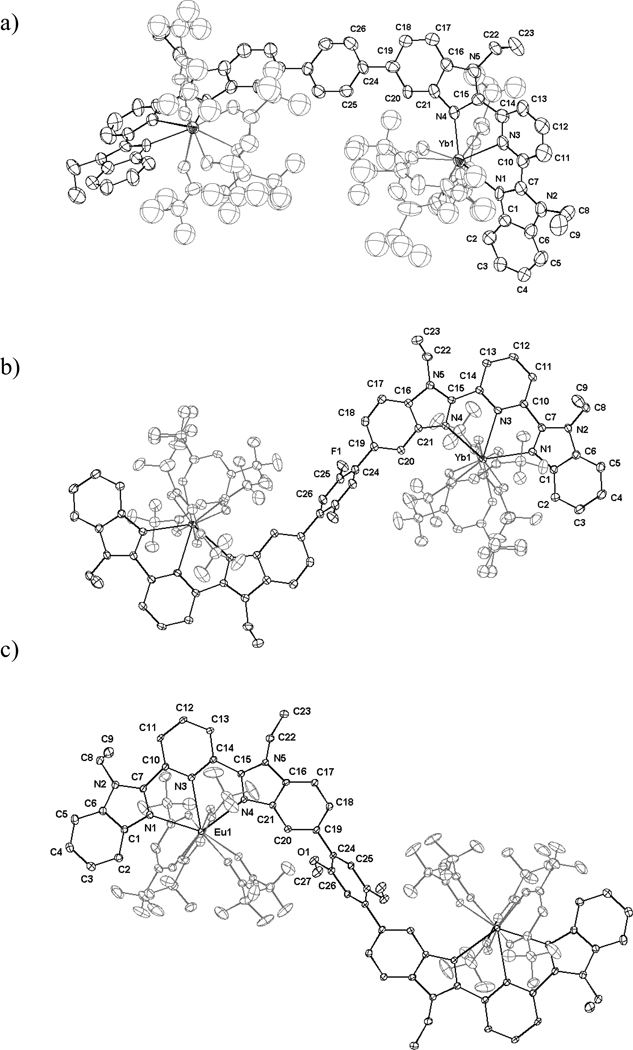

Reaction of Lk (1 eq) with [Ln(hfac)3diglyme] (2.0 eq, Ln = Gd, Eu, Yb, Y)38 in chloroform yields 50–90% of [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] as microcrystalline precipitates (Table S2). Subsequent re-crystallizations by slow diffusion of diethylether into saturated acetonitrile/chloroform solutions of the complexes provide X-ray quality prisms for [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] (1), [Y2(L3)(hfac)6] (2), [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] (3) and [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (4) (Table S3). The crystal structures can be described as the packing of neutral dinuclear complexes held together by networks of intermolecular π-stacking interactions (Figs S6–S8). As expected, the size of the lanthanide cation does not greatly affect the crystal organization and [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] (1) is thus isostructural with [Y2(L3)(hfac)6] (2, Table S3 and Fig. S9). Only the former complex will be considered for further comparisons with 3 and 4. Each dinuclear complex possesses a crystallographic symmetry element passing through the substituted phenyl ring leading to a twofold U-shaped arrangement of the ligand strand in [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] (Yb⋯Yb = 12.624(2) Å, Fig. 7a), and centrosymmetrical S-shaped geometries in [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] (Yb⋯Yb = 14.77(1) Å, Fig. 7b) and [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (Eu⋯Eu = 14.928(3) Å, Fig. 7c).

Figure 7.

ORTEP views of the molecular structures are shown with the numbering schemes for a) [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6], b) [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] and c) [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] in the crystal structures of 1, 3 and 4. Thermal ellipsoids are represented at the 30% probability level and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Each trivalent lanthanide cation in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] is nine-coordinated by the three nitrogen donor atoms of the 2,6-bis(benzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine moiety and the six oxygen atoms of three bidentate hfac− anions, and form distorted polyhedra (Fig. 7). The Ln-O39 and Ln-N40 distances are typical of those found in other complexes (Table 3 and Tables S4–S11). Close scrutiny of the bond valences νLn,N and νLn,O (Tables S12–S14)41 shows that the replacement of the nitrate groups found in the model complex [Eu(L6)(NO3)3] (νEu,N(bzim) = 0.39, νEu,N(py) = 0.29 and νEu,O-nitrate = 0.28)40 with hexafluoroacetylacetonate in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] is accompanied by a significant reduction of νLn,N(bzim) and νLn,N(py) that is compensated by a parallel increase of νLn,O-anion (Table 3). We deduce that the hfac− counter-anions exhibit stronger interactions with Ln(III) than does NO3−, and the resulting decrease of the metal’s effective positive charge reduces the affinity of Ln(hfac)3 for the tridentate site in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Ln⋯Ln, Ln-N and Ln-O Distances (Å), Bond Valences (νLn,j)a and Bond Valence Sums (VLn)b in the Crystal Structures of [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] (1), [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] (3) and [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (4).

| [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] | [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] | Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ln-Nbzim c /Å | 2.443(4) | 2.476(4) | 2.581(1) |

| Ln-Npy /Å | 2.519 | 2.526 | 2.61 |

| Ln-O d /Å | 2.38(8) | 2.36(7) | 2.43(2) |

| Ln⋯Ln /Å | 12.624 | 14.77 | 14.928 |

| νLn, N(bzim)c | 0.359(4) | 0.328(4) | 0.322(1) |

| νLn,N(py) | 0.292 | 0.287 | 0.297 |

| νLn,Od | 0.33(6) | 0.34(6) | 0.35(2) |

| VLn | 2.964 | 2.980 | 3.039 |

νLn,j = e[(RLnj−dLn,j)/b], whereby dLn,j is the Ln-donor atom j distance. The valence bond parameters RLn,N and RLn,O are taken from refs 41e,f and b = 0.37 Å.

.41

Each value is the average of twoc or sixd bond distances and the numbers between brackets correspond to the standard deviations affecting the average values (the original uncertainties affecting each bond length are given in Tables S4, S8 and S10; bzim = benzimidazole and py = pyridine).

This trend is further substantiated by the observed decrease, 2–3 orders of magnitude, in the thermodynamic formation constants that are measured in acetonitrile when NO3− counter-anions (equilibrium 9; , see scheme 1 for the structure of L7)42 are replaced with hfac− counter-anions (equilibrium 10, , see appendix 1 for details).

| (9) |

| (10) |

Finally, it is worth noting that the stepwise insertion of bulkier substituents onto the central phenyl ring (X = H (L3), < X = F (L4) ≈ X = OCH3 (L5)) substantially increases the inter-annular phenyl-benzimidazole interplanar angles from α = 25.26(4)° in [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] to α = 54.1(1)° in [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] and to 45.34(4)° in [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (Tables S5, S9 and S11). This change in twist angle should affect the HOMO-LUMO gap in the various complexes, but it is not expected to change the trend in the HOMO-LUMO gap through the series, i.e., (Fig. S5).

Photophysical properties of the dinuclear complexes [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] (Ln = Gd, Eu and Lk = L3–L5)

Taking estimated in acetonitrile for equilibrium 10, we calculate that millimolar concentrations are required for ensuring that more than 80% of [Y2(Lk)(hfac)6] is formed in solution (Table S15). Because of the sub-millimolar solubilities of these complexes (Fig. S10), the photophysical investigations were strictly limited to solid state samples, where quantitative complexation has been firmly established by X-ray diffraction studies. According to standard protocols,2,26 the ligand-centered photophysical properties were investigated in the gadolinium complexes [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] because paramagnetic Gd(III) induces some mixing of ligand and metal wavefunctions, similar to that expected upon complexation of luminescent Eu(III) (heavy-atom effect and paramagnetic coupling).27 Moreover, Gd(III) does not possess low-lying metal-centered excited state levels that could participate in energy transfer, from either Lk(1ππ*) or Lk(3ππ*).43

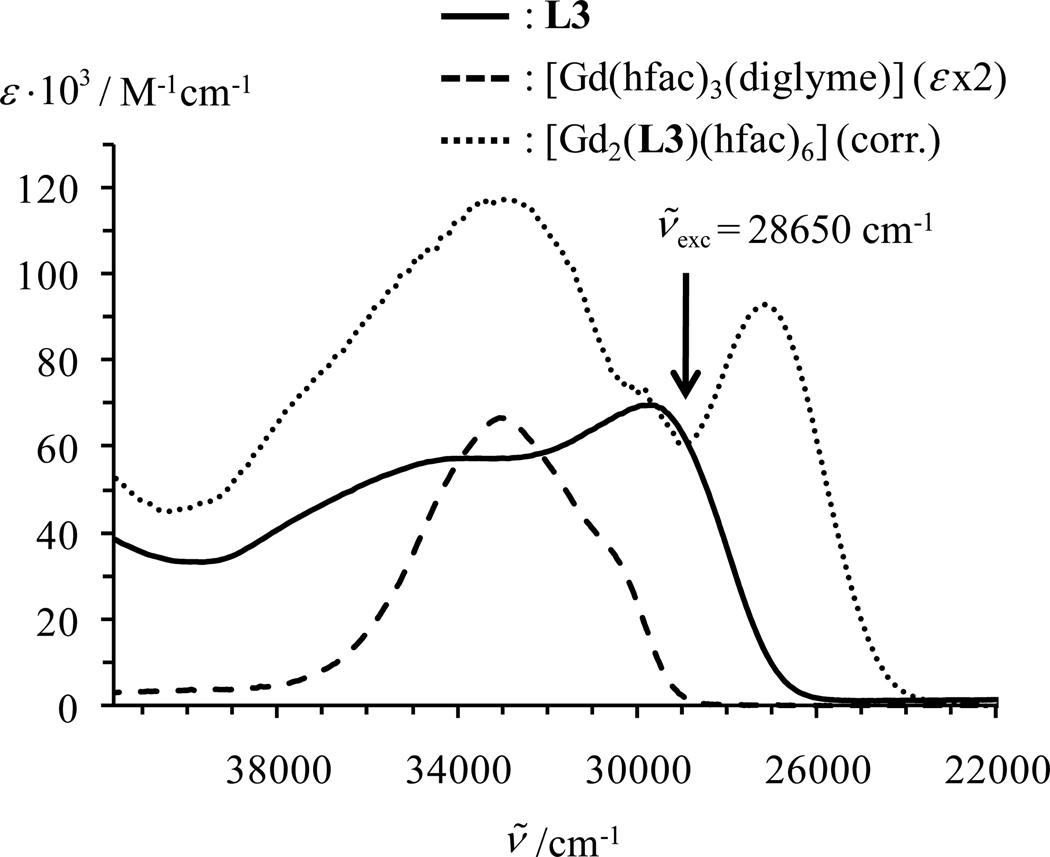

The UV-vis absorption spectrum of [Gd2(L3)(hfac)6], corrected for partial dissociation, appears to combine the characteristics of the [Gd(hfac)3] unit at high energy (a main band is present at 33060 cm−1) with that of the L3 coordinated Gd(III) at low energy; the L3-centred π→π* transition is split by a Davydov exciton coupling, giving bands with apparent maxima at 30000cm−1 and 27000 cm−1, Fig. 8).44,45

Figure 8.

UV-vis absorption spectra are shown for L3 (CH2Cl2, solid line), [Gd(hfac)3(diglyme)2] (CH3CN, dashed line, ε × 2 for comparison purpose) and [Gd2(L3)(hfac)6] (CH2Cl2:CH3CN 1:1, dotted line) recorded at 293 K. The absorption spectrum of the latter ternary complex is corrected for partial decomplexation according to equilibrium 10 with (see appendix 2).

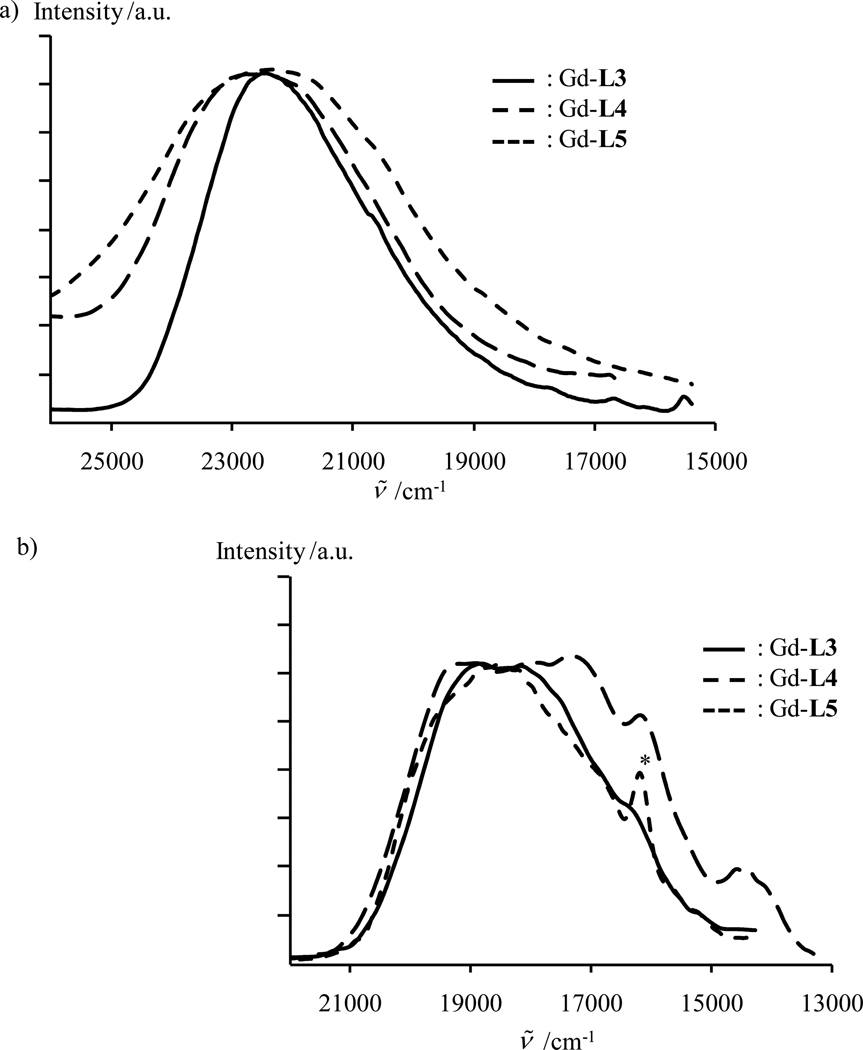

The Lk-centered irradiation of solid state samples of [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] at ν̄exc = 28650 cm−1 provides a short-lived fluorescence that is centered near E(1ππ*) = 23000-22000 cm−1 with a lifetime τL (F) = 30–70 ps at 293 K (see Fig. 9a and Table 1) and a weaker long-lived phosphorescence band located at lower energy (E(3ππ*) = 19500-19000 cm−1 τL (P) = 123–160 µs at 293 K, Fig. 9b and Table 1). Since the excited states centered onto the coordinated hfac− anions are located at energies exceeding 30000 cm−1 (Fig 8),46 they cannot significantly contribute to the luminescence process in the target complexes [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] for excitation energies below 29000 cm−1, and the emission characteristics collected for the Gd-complexes in Tables 1 and 2 can be thus safely assigned as originating from the coordinated bis-tridentate ligand strands. The predicted, and observed, decrease of the energy of the Lk(1ππ*) excited states along the series L4 > L3 > L5 (Fig. 6) is globally retained upon complexation in [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] (Fig. 9a), as well as the energies characterizing the ligand-centered triplet states (Fig. 9b). Compared to the free ligands, the values of the fluorescence quantum yields are reduced by an order of magnitude in the associated Gd-complexes, while the characteristic 1ππ* lifetimes only decrease by a factor of three to five (Table 2, columns 5 and 6). Consequently, we deduce from eq 1 that the radiative rate constants of the ligand-centered 1ππ* levels are significantly reduced in [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] while the overall the nonradiative processes, increases (Table 2, columns 7 and 8).27 Because I(3ππ*)/I(1ππ*) = 2.1·10−4 for the similar tridentate binding unit in L6a,21 we can reasonably assume that kISC(Lk) ≪ kISC([Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6], and in the Gd-complexes can then be roughly estimated with eq 11 (Table 2, column 9).47 Once is obtained, then (i) the value of ηISC can be found by using eq 4 (Table 2, column 10), (ii) is obtained from the definition of the luminescence lifetime (Table 2, column 11) and (iii) Aπ is calculated with eq 8 (Table 2, column 12).

| (11) |

Figure 9.

Panel a) shows fluorescence and panel b) shows phosphorescence (delay time after flash 0.1 ms) spectra of [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5, solid state, 77 K, ν̄exc = 28650 cm−1). The * indicates contamination with traces of highly-emissive Eu(III) cations.

Despite the non-negligible uncertainties affecting , and ηISC values because of the demanding experimental determination of very short 1ππ* fluorescence lifetimes (Table 2, column 6), we conclude that the efficient ISC processes observed in [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6] (ηISC ≈ 50–80%) have two concomitant origins. First, the well-known favorable heavy atom and paramagnetic effects induced by the coordination of open-shell Ln(III) to aromatic ligands makes the intersystem crossing rate constant comparable with other non-radiative processes.27 Second, the specific polarization of the aromatic system by the coordinated cation decreases the π-conjugation lengths Aπ(Table 2, column 12) and the radiative rate constants (eq 8; Table 2, column 7) in the Gd-complexes

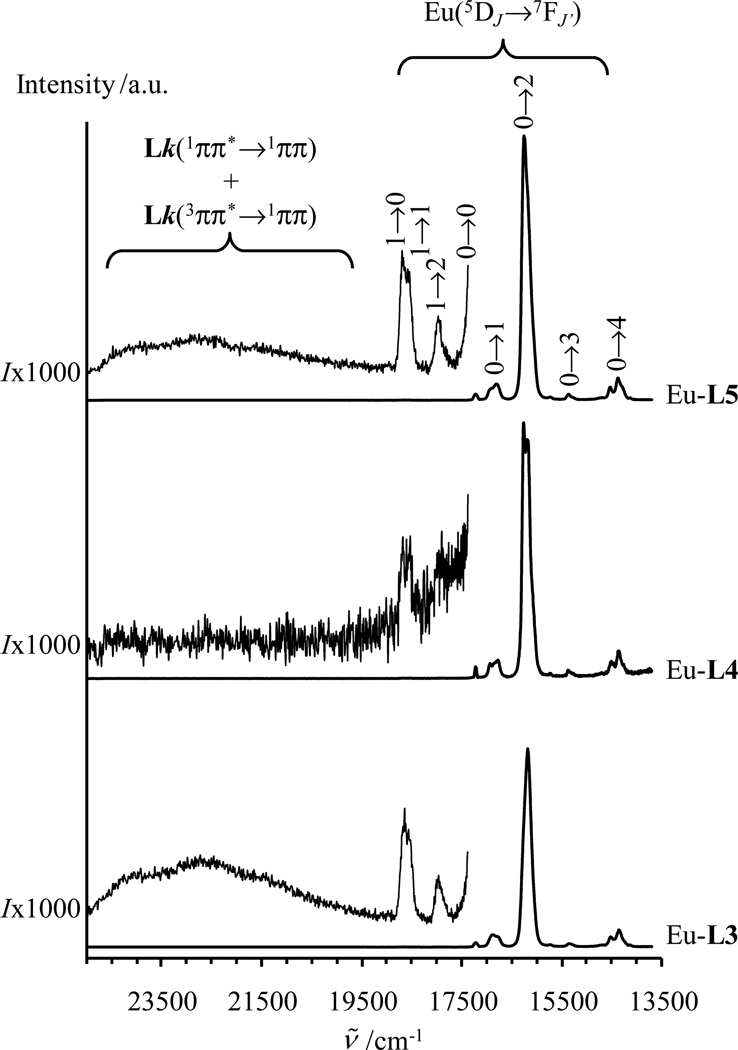

When Gd(III) is replaced with emissive Eu(III) in the complexes [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6], irradiation in the ligand-centered excited states at ν̄exc = 28650 cm−1 produces weak ligand-centered fluorescence (1ππ*→1ππ) with traces of phosphorescence (3ππ*→1ππ) and an intense red signal arising from Lk→Eu energy transfer followed by Eu(5D1) and Eu(5D0)-centered luminescence (Figs. 3 and 10). The intensities of the Eu(5D1→7FJ) transitions are extremely small compared to the luminescence arising from the Eu(5D0→7FJ) transitions,11a and the emission spectra are dominated by the hypersensitive forced electric dipolar Eu(5D0→7F2) transition centered at 16340 cm−1. These two spectral characteristics are well-documented for low-symmetry tris-β-diketonate Eu(III) complexes (Fig. 10).23,25 With the naked eye, one immediately notices that the strong red luminescence obtained upon UV irradiation of solid samples is brightest for [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6]. This qualitative observation is substantiated by measurements of the global absolute quantum yields (upon excitation of the ligand excited states and monitoring the Eu3+ emission) reaching 20.6(7)% for [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6], 9.3(3)% for [Eu2(L3)(hfac)6] and 9.2(3)% for [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (solid state, 293K, Table 4, entry 6). Using Einstein’s result35 for the spontaneous radiative emission rate A, given here as eq 12, AMD,0 = 14.65 s−1 is obtained for the magnetic dipolar Eu(5D0→7F1) transition. This calculation used n = 1.5 for the refractive index of the solid, and Itot/IMD was estimated as the ratio between the total integrated emission arising from the Eu(5D0) level to the 7FJ manifold and the integrated intensity of the magnetic dipolar Eu(5D0→7F1) transition.18a,22b

| (12) |

Figure 10.

Luminescence emission spectra are shown for [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5, solid state, 293 K, ν̄exc = 28650 cm−1).

Table 4.

Experimental Global and Intrinsic Quantum Yields, Luminescence Lifetimes and Calculated Energy Migration Efficiencies and Rate Constants for [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] in the solid state at 293 K.

| Compound | [Eu2(L3)(hfac)6] | Eu2(L4)(hfac)6] | [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu-centered luminescence | ||||

| Itot/IMDa | 17.5(3) | 18.2(3) | 18.6(3) | |

| (eq 12) | 0.86(2) | 0.90(2) | 0.92(2) | |

| τEu /ms | 0.88(4) | 0.83(15) | 1.06(16) | |

| (eq 3) | 0.68(2) | 0.76(2) | 0.95(2) | |

| (eq 3) | 0.21(1) | 0.23(4) | 0.031(3) | |

| Global quantum yield and sensitization efficiency | ||||

| 0.092(3) | 0.206(7) | 0.093(3) | ||

| (eq 7) | 0.122(7) | 0.28(5) | 0.096(8) | |

| Energy migration and associated rate constants (method 1)b | ||||

| ηISCc | 0.60(3) | 0.6(1) | 0.9(5) | |

| (eq 7) | 0.20(2) | 0.47(14) | 0.11(6) | |

| (eq 13) | 2.1(3) | 5.5(2.3) | 0.9(7) | |

| 8.1(5) | 6.3(8) | 7.1(3) | ||

| Energy migration and associated rate constants (method 2)d | ||||

| 0.10(1) | 0.10(3) | 0.11(1) | ||

| (eq 15) | 2(1) | 4(3) | 2.0(9) | |

| (eq 16) | 0.19(2) | 0.38(12) | 0.22(2) | |

| ηISC (eq 7) | 0.65(8) | 0.7(3) | 0.44(6) | |

| kISC/ns−1 (eq 4) | 10.8(1.5) | 11(5) | 16(9) | |

Ratio between the total integrated emission for the Eu(5D0) level to the 7FJ manifold and the integrated intensity of the magnetic dipolar Eu(5D0→7F1) transition.

A schematic illustration of these numerical data is shown in Fig. 11.

Taken from Table 2 for the analogous complexes [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6].

A schematic illustration of these numerical data is shown in Fig. S13.

The integration of the corrected luminescence spectra recorded for [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] (Fig. 10) gives 17.5 ≤ Itot/IMD ≤ 18.6 (Table 4, entry 1), which translate into comparable radiative rate constants for the three complexes (Table 4, entry 2). Combining these results with the experimental Eu(5D0) lifetimes (Table 4, entry 3) provides efficient intrinsic quantum yields (eq 3, Table 4 entry 4), whose magnitudes only smoothly increase along the series , a trend which contrasts with that found for the global quantum yields (Table 4 entry 6), but in line with recently determined in acetonitrile at 293 K.36 Application of eq 7 yields the sensitization efficiency , which is twice as large for [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6] (0.28(5)) than for [Eu2(L3)(hfac)6] (0.122(7)) or [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (0.096(8), Table 4, entry 7). Considering that the values of ηISC estimated for the respective Gd(III) complexes also hold for the Eu(III) complexes (Table 4, entry 8), we deduce values for (see Table 4, entry 9). If we assume that the Lk(3ππ*)→Eu(III) energy transfer processes is the only additional perturbation affecting the deactivation of 3ππ* upon replacement of Gd(III) with Eu(III) in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6], the assumption (Table 4, entry 11) is valid and eq 5 transforms into eq 13, from which the global rate constants for energy transfer can be estimated (Table 4, entry 10)

| (13) |

Figs 11, S13 and S14 summarizes the efficiency and rate constant for each step contributing to the ligand-centered sensitization processes in the three complexes [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5). Focusing on the average numerical values, we conclude that the Lk(3ππ*)→Eu(III) energy transfer process represents the bottleneck which limits the global quantum yield, whatever the choice of the substituents. However, the rate limiting step is fastest for the difluoro-phenyl spacer found in [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6]. Because the Fermi golden rule implies that the probability WDA of any resonant energy transfer depends on the spectral overlap integral ΩDA between the absorption spectrum of the acceptor A and the emission spectrum of the donor D (eq 14),16d,20 we hypothesize that the global blue-shifted ligand-centered emission observed for the fluorinated complex [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6] causes a larger spectral overlap with Eu(5D2) and/or Eu(5D1) levels of Eu(III) acting as accepting levels (Fig. 11).48 We cannot however completely exclude some concomitant changes in the perturbation terms |〈DA*|H'| D*A〉|2 due to specific stereoelectronic characteristics of the ground and excited states in [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6].

| (14) |

Figure 11.

The figure shows the Jablonski diagram established for [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k = 3–5) and collects the efficiencies of intersystem crossings (ηISC), energy transfers , intrinsic quantum yields and global quantum yields for the global ligand-mediated sensitization of Eu(III) (solid-state, 293 K). Color codes : [Eu2(L3)(hfac)6] = blue, [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6] = red and [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] = green.

However, the propagation of uncertainties49 prevents a deeper interpretation of ηISC and , especially for [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6], by using the latter approach (termed method 1 in Table 4, entries 8–9). This limitation can be tentatively overcome when the intensity of the residual ligand-centered triplet state phosphorescence in [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6] is strong enough to allow the reliable experimental determination of its characteristic lifetime (Table 4, entry 12). Relying on the usual assumption that the Lk(3ππ*)→Eu(III) energy transfer process (characterized by in Fig. 3) is the only additional perturbation affecting the deactivation of 3ππ* upon replacement of Gd(III) with Eu(III) in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6], (Table 4, entry 13) can be deduced from eq 15 (termed method 2 in Table 4; (Table 1, column 7) and (Table 4, entry 12) are the experimental luminescence lifetimes for the ligand-centered triplet state in the complexes with Gd(III) and Eu(III), respectively). can be then estimated with eq 16 (Table 4, entry 14).

| (15) |

| (16) |

The values for (Table 4, entry 15) are obtained from the known sensitization factors ηsens (Table 4, entry 7) without resorting to the recording of sub-nanosecond fluorescence lifetimes for [Gd2(Lk)(hfac)6]. Reasonably assuming that ηISC is identical in the dinuclear Gd(III) and Eu(III) complexes, we can calculate kISC by using eq 4 (Table 4, entry 16). Both approaches converge toward the same average values for the rate constants within experimental errors (Fig. 11 and S13–S14), and a close scrutiny of the uncertainties shows that the accuracy of each technique is complementary.

Experimental section

Chemicals were purchased from Strem, Acros, Fluka AG, and Aldrich, and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. The synthesis of the starting compound 1 is described in the Supporting Information (Scheme S1). The hexafluoroacetylacetonate salts [Ln(hfac)3C8H12O3] were prepared from the corresponding oxide (Aldrich, 99.99%, appendix 3).38 Acetonitrile and dichloromethane were distilled over calcium hydride. Silica gel plates Merck 60 F254 were used for thin layer chromatography (TLC) and Fluka silica gel 60 (0.04–0.063 mm) or Acros neutral activated alumina (0.050–0.200 mm) was used for preparative column chromatography.

Preparation of 2

A 20 mL THF solution of 1,4-dibromobenzene (4.72 g, 20 mmol) was added dropwise to a suspension of magnesium shavings (1.06 g, 43.6 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL) under an inert atmosphere. The mixture was refluxed for 24–48 h until the appearance of a grey precipitate. Trimethylborate (5 mL, 4.66 g, 44.8 mmol) in THF (50 mL) was added and the mixture refluxed for 2 h. The white gel was poured into aq. hydrochloric acid (2 m, 200 mL) and stirred for 1 h at RT. The clear solution was extracted with diethylether (4×200 mL) and the combined organic phases were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated to dryness. Recrystallization from hot water (200 mL) gave 2 as transparent crystals (1.6 g, 9.6 mmol, 48%). 1H NMR (d6-acetone; 400 MHz): δ = 7.86 (s, 4H), 7.13 (s, 4H). ESI-MS (negative mode/CH3OH) : m/z 165.3 ([M−H]−), 179.1 ([M+CH3OH-H]−).

Preparation of 3

1–4 dimethoxy benzene (1.38 g, 10.0 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of dry hexane and the solution was kept at 0 °C. nBuLi (37.5 mL, 1.6 M in hexane, 60.0 mmol) and TMEDA (4.5 mL, 30.0 mmol) were slowly added to the solution during 30 min. The resulting yellow solution was stirred at room temperature for 48 h under inert atmosphere and was cooled at 0 °C. B(OMe)3 (7.6 mL, 66 mmol) was added via a syringe under vigorous stirring and produced a white precipitate. After two hours, the turbid solution was evaporated to dryness. The white solid was poured into aq. hydrochloric acid (1M, 200 mL). The clear solution was extracted with diethylether (4×200 mL) and the combined organic phases were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated to dryness to give 3 as a white powder (0.70 g, yield = 31%). 1H NMR (d6-DMSO; 400 MHz): δ = 7.15 (s, 2H), 3.77 (s, 6H). ESI-MS (positive mode/CH3OH): m/z 226.4 ([M+H).

Preparation of 4

1–4 dibromo 2–5 difluorobenzene (1.23 g, 4.7 mmol) and PdIIdppfCl2 (112 mg, 0.153 mmol, dppf = 1,1’-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene) were dissolved in degassed DMF (40 mL). The resulting red solution was slowly transferred via a cannula in a schlenk vessel charged with bis(pinacolato)diboron (2.54 g, 10.0 mmol) and potassium acetate (2.03 g, 20.5 mmol). The resulting red mixture was heated at 80 °C for 24 h. The cooled black solution was partitioned between dichloromethane (100 mL) and half-sat. aq. NaCl (100 mL). The organic layer was separated, washed with water (2×100mL), dried (MgSO4) and evaporated. The black solid was loaded in a Kugelrohr apparatus and heated at 140 °C under vacuum to give white crystals of 4 (170 mg; yield = 10%). 1H NMR (CDCl3; 400 MHz): δ = 7.33 (t, JH-F=6.6 Hz, 2H), 1.35 (s, 24H). ESIMS (positive mode/CH3OH): m/z 385.3 ([M+H3O]+).

Preparation of L3

Compounds 1 (0.89 g, 2.0 mmol) and 2 (166 mg, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in dioxane/ethanol (30 mL:20 mL) containing cesium fluoride (1.37 g, 9 mmol) under an inert atmosphere. The turbid solution was degassed by nitrogen bubbling during 20 min. Pd(PPh3)4 (100 mg, 0.09 mmol) was added and the resulting yellow solution was stirred for 20 min at RT, then refluxed for 24 h. After evaporation to dryness, the solid residue was partitioned between dichloromethane (150 mL) and half-sat. aq. NaCl (200 mL). The aq. phase was separated, extracted with dichloromethane (200 mL) and the combined organic phases were dried (Na2SO4), filtered and evaporated to dryness. The crude brown solid was purified by column chromatography (Silicagel, CH2Cl2:CH3OH:NEt3 = 99.5:0:0.5→96.5:3:0.5) to give a pale yellow solid, which was crystallized from dichloromethane:ethanol to give L3 as a pale yellow powder (0.58 g, 0.71 mmol, yield = 71%). 1H NMR (CDCl3; 400 MHz): δ =1.40 (t, 3J = 7 Hz, 3H), 1.42 (t, 3J = 7 Hz, 3H), 4.83 (q, 3J = 7 Hz, 2H), 4.85 (q, 3J = 7 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (multiplet, 4H), 7.51 (dd, 3J = 6 Hz, 4J = 2 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (d, 3J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (dd, 3J = 7 Hz, 4J = 1 Hz, 2H), 7.83 (s, 4H), 7.91 (dd, 3J = 7 Hz, 4J = 1 Hz, 2H), 8.10 (t, 3J = 7 Hz, 2H), 8.18 (d, 4J = 1 Hz, 2H), 8.39 (d, 3J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.41 (d, 3J = 8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz): δ = 150.64, 150.18, 150.04, 149.98, 143.67, 143.05, 140.39, 138.23, 136.16, 136.09, 135.70, 127.94, 125.87, 125.81, 123.66, 123.43, 122.90, 120.47, 118.62, 110.60, 110.37, 40.09, 39.91, 15.60, 15.54. ESI-MS (positive mode/CH3OH):m/z 405.5 ([L3+2H]2+), 810 ([L3+H]+). Elemental analyses: calcd for C52H44N10·H2O %C 75.52, %H 5.60, % N 16.94. Found %C 75.60, %H 5.47, %N 16.72.

Preparation of L4

Compounds 1 (311 mg, 0.70 mmol) and 4 (106 mg, 0.29 mmol) were dissolved in dioxane/ethanol (50 mL:30 mL) containing cesium fluoride (200 mg, 1.4 mmol) under an inert atmosphere. The turbid solution was degassed by nitrogen bubbling for 20 min. Pd(PPh3)4 (50 mg, 0.04 mmol) was added and the resulting yellow solution stirred for 20 min at RT, then refluxed for 24 h. After evaporation to dryness, the solid residue was partitioned between dichloromethane (150 mL) and half-sat. aq. NaCl (200mL). The aq. phase was separated, extracted with dichloromethane (200 mL), and the combined organic phases were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The crude brown solid was purified by column chromatography (Silicagel, CH2Cl2:CH3OH:NEt3 = 99.5:0:0.5→96.5:3:0.5) to give a yellow solid, which was crystallized from dichloromethane:petroleum ether to give L4 as a off-white powder (110 mg, 0.13 mmol, yield = 45%). NMR 1H (400 MHz CDCl3): 1.39 (t, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.42 (t, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 4.82 (q, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 4.85 (q, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (m., 2H), 7.40 (t, 3JH-F=4JH-F=8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (dd, 3J = 6.3 Hz, 4J=1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, 3J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, 3J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (dd, 3J = 7.0 Hz, 4J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (t, 3J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 8.39 (dd, 3J = 7.9 Hz, 4J=2.0 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS: m/z 423.4 ([L4+2H]2+), 845.3 ([L4+H]+). NMR 13C (101 MHz CDCl3) : 147.14, 146.51, 146.24, 139.95, 139.72, 135.25, 133.16, 133.08, 127.84 (1JC–F= 350.2 Hz, 4JC–F=10.1 Hz), 127.02, 126.87 (2JC–F=3JC–F=11.6 Hz), 123.60, 123.49, 122.53, 121.45, 120.72, 118.77, 118.40, 116.01 (2JC–F= 3JC–F=17.5 Hz), 108.95, 108.86, 42.43, 42.24, 19.24, 19.19. Elemental analyses: calcd for C52H42N10F2 %C 73.91, %H 5.01, % N 16.58. Found %C 72.66, %H 4.70, %N 15.95.

Preparation of L5

Compounds 1 (0.86 g, 1.94 mmol) and 3 (218 mg, 0.97 mmol) were dissolved in dioxane/ethanol (30 mL:20 mL) containing cesium fluoride (1.37 g, 9 mmol) under an inert atmosphere. The turbid solution was degassed by nitrogen bubbling for 20 min. Pd(PPh3)4 (150 mg, 0.13 mmol) was added and the resulting yellow solution was stirred for 20 min at RT, then refluxed for 24 h. After evaporation to dryness, the solid residue was partitioned between dichloromethane (150 mL) and half-sat. aq. NaCl (200mL). The aq. phase was separated, extracted with dichloromethane (200 mL), and the combined organic phases were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The crude brown solid was purified by column chromatography (Silicagel, CH2Cl2:CH3OH:NEt3 = 99.5:0:0.5→96.5:3:0.5) to give a yellow solid, which was crystallized from dichloromethane:ethanol to give L5 as a microcrystalline yellow powder (0.42 g, 0.48 mmol, yield = 50%). NMR 1H (400 MHz CDCl3) : 1.39 (t, 3J = 7 Hz, 3H), 1.42 (t, 3J = 7 Hz, 3H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 4.82 (q, 3J = 7 Hz, 2H), 4.84 (q, 3J = 7 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (s, 2H), 7.38 (m., 4H), 7.51 (dd, 3J = 6 Hz, 4J = 2 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (d, 3J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (dd, 3J = 7 Hz, 4J = 1 Hz, 2H), , 7.89 (dd, 3J = 7 Hz, 4J = 1 Hz, 2H), 8.08 (t, 3J = 7 Hz, 2H), 8.14 (d, 4J = 1 Hz, 2H), 8.37 (d, 3J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.39 (d, 3J = 8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.90, 150.46, 150.18, 150.15, 150.04, 143.15, 143.08, 138.25, 136.13, 135.41, 133.43, 130.68, 125.81, 123.68, 122.92, 121.20, 120.51, 115.28, 110.39, 109.85, 56.60, 40.06, 39.97, 15.66, 15.58. ESI-MS (positive mode/CH3OH): m/z 435.6 ([L5+2H]2+), 869.3 ([L5+H]+). Elemental analyses: calcd for C54H48N10O2.0.15CHCl3 %C 73.30, %H 5.47, % N 15.79. Found %C 73.35, %H 5.23, %N 15.66.

Preparation of the complexes [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6] (k=3–5)

In a typical procedure, 0.05 mmol (ca 40–45 mg) of [Ln(hfac)3diglyme] was dissolved in chloroform (2 ml) and then added to 0.024 mmol of ligand (ca. 20 mg) in chloroform (1 mL). For ligands L3 and L5, precipitation occurred immediately. For ligand L4, the solution was cooled for 2 h at −20 °C until precipitation. Complexes were collected as pale yellow microcrystalline powders by filtration and dried under vacuum at 70 °C (yields = 50–90 %, Table S2). Monocrystals suitable for X-Ray diffraction were obtained by reacting 0.015 mmol of [Ln(hfac)3diglyme] in acetonitrile (2 mL) with 0.006 mmol of ligand in chloroform (0.2 mL). Slow evaporation or slow diffusion of diethyl ether yielded yellow prisms.

Spectroscopic measurements

1H, 19F and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K on Bruker Avance 400 MHz and Bruker DRX-300 MHz spectrometers. Chemical shifts are given in ppm with respect to TMS. Pneumatically-assisted electrospray (ESI-MS) mass spectra were recorded from 10−4 M solutions on an Applied Biosystems API 150EX LC/MS System equipped with a Turbo Ionspray source®. Elemental analyses were performed by Dr. H. Eder or K. L. Buchwalder from the Microchemical Laboratory of the University of Geneva. Electronic absorption spectra in the UV-Vis were recorded at 20 °C from solutions in CH2Cl2 with a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 900 spectrometer using quartz cells of 10 or 1 mm path length. Some of the excitation and emission spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer LS-50B spectrometer equipped for low-temperature measurements. The quantum yields Φ for the free ligands in solution have been recorded through the relative method with respect to quinine sulfate 6.42 10−6 M in 0.05 M H2SO4 (refractive index 1.338 and quantum yield 0.546),37 and calculated using the equation

where x refers to the sample and r to the reference; A is the absorbance, ν the excitation wavenumber used, I the intensity of the excitation light at this energy, n the refractive index and D the integrated emitted intensity. Luminescence spectra in the visible were measured using a Jobin Yvon–Horiba Fluorolog-322 spectrofluorimeter equipped with a Hamamatsu R928. Spectra were corrected for both excitation and emission responses (excitation lamp, detector and both excitation and emission monochromator responses). Quartz tube sample holders were employed. Quantum yield measurements of the solid state samples were measured on quartz tubes with the help an integration sphere developed by Frédéric Gumy and Jean-Claude G. Bünzli (Laboratory of Lanthanide Supramolecular Chemistry, École Polytechnique Féderale de Lausanne (EPFL), BCH 1402, CH- 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland) commercialized by GMP S.A. (Renens, Switzerland). Long luminescence lifetimes: triplet states (on Eu3+ and Gd3+ complexes) and lanthanide-centered luminescence lifetimes were measured at 293K using either a Nd:YAG Continuum Powerlite 8010 laser or a Quantel YG 980 (354 nm, third harmonic) as the excitation source. Emission was collected at a right angle to the excitation beam, and wavelengths were selected either by a Spectral Products CM 110 1/8 meter monochromator or interferential filters. The signal was monitored by a Hamamatsu R928 photomultiplier tube, and was collected on a 500 MHz band pass digital oscilloscope (Tektronix TDS 724C). Experimental luminescence decay curves were treated with Origin 7.0 software using exponential fitting models. Three decay curves were collected on each sample, and reported lifetimes are an average of at least two successful independent measurements. Rapid decays analysis (singlet states). The time-resolved luminescence decay kinetics was measured using the time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) technique. Samples were excited with the frequency-doubled output (centered at ~335 nm) of a synchronously pumped cavity dumped dye laser (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, model 599) using 4-(Dicyanomethylene)-2-methyl-6-(4-dimethylaminostyryl)-4H-pyran (DCM) as the gain medium; emission from the sample was collected at different wavelengths using a monochromator. The instrument response function had a full-width-at-half-maximum (fwhm) of ~40 ps. A 1 cm path length quartz cuvette was used for all the time-resolved measurements in solutions. Measurements with solid samples were performed in a quartz capillary. All measurements were performed at room temperature. Experiments were performed with a 1MHz laser repetition rate. Lifetime decay traces were fitted by an iterative reconvolution method with IBH DAS 6 decay analysis software.

X-Ray Crystallography

Summary of crystal data, intensity measurements and structure refinements for [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] (1), [Y2(L3)(hfac)6] (2), [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] (3) and [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (4) are collected in Table S3 (Supporting Information). All crystals were mounted on quartz fibers with protection oil. Cell dimensions and intensities were measured between 150–200 K on a Stoe IPDS diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Mo[Kα] radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Data were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects and for absorption. The structures were solved by direct methods (SIR97),50 all other calculation were performed with ShelX9751 systems and ORTEP52 programs. CCDC-822835 to CCDC-822838 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for 1–4, respectively. The cif files can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html (or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: (+ 44) 1223-336-033; or deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Comments on the crystal structure of [Yb2(L3)(hfac)6] (1), [Y2(L3)(hfac)6] (2)

These complexes were isostructural. [Ln2(L3)(hfac)6] were located on a twofold axis passing through the central phenyl ring and leading to only one half of the complex in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 7a). The crystal packing displayed channel voids along the [1 0 1] direction, where solvent molecules were highly disordered (Fig. S15). Squeezed calculations were thus performed and the solvent-free structures were refined. The presence of these channels may explain loss of solvent during the measurement which results in partial decomposition of the crystal and incomplete data collection. The CF3 units of the counter-anions showed some disorder and were refined isotropically. Hydrogen atoms were calculated and refined with restraints on bond lengths and bond angles.

Comments on the crystal structure of [Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] (3)

[Yb2(L4)(hfac)6] was located around an inversion center (in the center of the central phenyl ring) leading to only one half of the complex in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 7b). One CF3 unit (F5-F6-F7) was disordered (rotation) and was refined with identical isotropic displacement parameters on two sites with population parameters refined to PP = 0.54/0.46. H atoms were observed from the Fourier difference map and refined with restraints on bond lengths and bond angles.

Comments on the crystal structure of [Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] (4)

[Eu2(L5)(hfac)6] was located around an inversion center (in the center of the central phenyl ring) leading to only one half of the complex in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 7c). H atoms were observed from the Fourier difference map and refined with restraints on bond lengths and bond angles. All non H atoms were refined anisotropically.

Computational Details

The lowest electronic excitations at the optimized geometry of the ligands were obtained by means of TD-DFT calculations.53 The preliminary analyses of the excited state properties were made to estimate the weighting of the HOMO-LUMO transitions, which indeed provided the dominant component to the excitation energy for the studied systems. We thus limited the discussions of the electronic state of the ligands to the HOMO and LUMO orbitals obtained from ground-state DFT calculations. All calculations were performed using the Turbomole package (version 6.1)54 with the PBE functional.55 The geometry optimization was carried out without symmetry constraints, using the def2-TZVP basis set. In geometry optimization, the following thresholds were applied: 10−6 Hartree for energy difference and 10−3 Hartree/Bohr for the norm of the energy gradient. The HOMO-LUMO gap was calculated at the optimized geometry. The optimization started from the crystallographic structure. The dependence of the HOMO-LUMO gap on the torsion angle α between the 1,4-disubstituted phenyl spacer and the adjacent 5-benzimidazole rings (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information) was studied by a series of single-point calculations with all remaining degrees of freedom frozen.

Conclusion

Reactions of stoichiometric amounts of bis-tridentate ligands L3–L5 with [Ln(hfac)3diglyme] in acetonitrile quantitatively give the anhydrous and poorly soluble dinuclear complexes [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6]. While the limited affinity of the Ln(hfac)3 moiety for the tridentate binding unit prevents the formation of more than 80% of the complex at the highest accessible concentrations (0.1–0.5 mM), X-ray diffraction data unambiguously demonstrate the formation of the expected single-stranded dumbbell-shaped complexes. In the solid state, one finds that two globular nine-coordinate [N3Ln(hfac)3] units are connected by a di-substituted phenyl ring and separated by 1.3–1.5 nm. Except for the slightly larger solubility of [Ln2(L4)(hfac)6], objective arguments for selecting one specific phenyl spacer for further development of a polymerization protocol relies on the specific photophysical properties of the luminescent Eu(III) complexes. The thorough characterization of the energy kinetic rate constants responsible for the indirect sensitization of Eu(III) in [Eu2(Lk)(hfac)6], within the frame of a simple triplet energy migration scheme, shows that both ligand-centered intersystem crossing (ηISC ≈ 50–80%) and metal-centered luminescence are efficient. These kinetic steps are not very sensitive to the nature of the substituents studied. In contrast, the ligand-to-metal energy transfer acts as the rate limiting step , and it is significantly affected by the choice of the substituents. Whatever the origin of the favorable effect brought by fluorine substitution in [Eu2(L4)(hfac)6], it is worth stressing here that the energy transfer step is the only significant parameter amenable to tuning by minor substitutions of the central phenyl spacer in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6]. Though in line with innumerable previous reports, a safe assertion of this conclusion requires a comprehensive determination of all rate constants involved in the sensitization processes as shown in Fig 11. The two complementary and general methods used in this contribution exploit the routine experimental determination of global and intrinsic quantum yields as a starting point. Method 1 focuses on the measurement of short 1ππ* fluorescence lifetimes, and data obtained for the free ligand and for the corresponding Gd(III) complex are compared. The accuracy is strongly dependent on the quality of the ps→ns timescale lifetime data. Alternatively, the method 2 relies on the determination of more easily accessible long 3ππ* lifetimes, and compares the data obtained for the Gd(III) and Eu(III) complexes. In this case, the accuracy is limited by the faint (if any) intensities detected for the residual 3ππ*→1ππ phosphorescence in the emissive Eu(III) complexes at room temperature. It is obvious that the simultaneous use of both methods will produce more reliable results, but systems which escape one approach, for instance [Ln2(L5)(hfac)6] because of the ultra-short fluorescence lifetime of the Gd(III), can be still investigated following the alternative protocol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. DHW and SP acknowledge support from the National Institute of Health, via NIH grant R21-EB008257-01A1 and DHW acknowledges partial support from the National Science Foundation (CHE-0718755). SP acknowledges support in France from la Ligue contre le Cancer and from Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM). The work in France was carried out within the COST Action D38. KAG acknowledges support from the Mary E. Warga Predoctoral Fellowship

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Details for the determination of stability constants (appendix 1) and for the correction of electronic absorption spectra (appendix 2). Synthesis of starting materials (appendices 3 and 4). Tables of 1H NMR shifts, elemental analyses, crystal data, geometric parameters and bond valences. Figures showing DFT calculations, 1H NMR spectra, electronic absorption and emission spectra, Jablonski diagram and crystal packing. A CIF file for 1–4. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes and References

- 1.(a) Binnemans K. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:4283–4374. doi: 10.1021/cr8003983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vigato PA, Peruzzo V, Tamburini S. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009;253:1099–1201. [Google Scholar]; (c) Brito HF, Malta OML, Felinto MCFC, Teotonio EES. The Chemistry of Metal Enolates. chap 3. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. pp. 131–184. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Evans RC, Douglas P, Winscom CJ. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250:2093–2126. [Google Scholar]; (b) de Bettencourt-Dias A. Dalton Trans. 2007:2229–2241. doi: 10.1039/b702341c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Katkova MA, Bochkarev MN. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:6599–6612. doi: 10.1039/c001152e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Shunmugam R, Tew GNJ. Polymer Science, Part A: Polymer Chem. 2005;43:5831–5843. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shunmugam R, Tew GN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13567–13572. doi: 10.1021/ja053048r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lou X, Zhang G, Herrera I, Kinach R, Ornatsky O, Baranov V, Nitz M, Winnik MA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6111–6114. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Balamurugan A, Reddy MLP, Jayakannan M. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:14128–14138. doi: 10.1021/jp9067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Oxley DS, Walters RW, Copenhafer JE, Meyer TY, Petoud S, Edenborn HM. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:6332–6334. doi: 10.1021/ic9002324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wild A, Winter A, Schlütter F, Schubert US. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1459–1511. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00074d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Chen X-Y, Yang X, Holliday BJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1546–1547. doi: 10.1021/ja077626a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu B, Bao Y, Du F, Wang H, Tian J, Bai R. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:1731–1733. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03819a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borkovec M, Hamacek J, Piguet C. Dalton Trans. 2004:4096–4105. doi: 10.1039/b413603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Ende BM, Aarts L, Meijerink A. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:11081–11095. doi: 10.1039/b913877c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Auzel F. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:139–173. doi: 10.1021/cr020357g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang F, Liu X. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:976–989. doi: 10.1039/b809132n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Koullourou T, Natrajan LS, Bhavsar H, Pope SJA, Feng J, Narvainen J, Shaw R, Scales E, Kauppinen R, Kenwright AM, Faulkner S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2178–2179. doi: 10.1021/ja710859p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nonat AM, Quinn SJ, Gunnlaugsson T. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:4646–4648. doi: 10.1021/ic900422z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Andrews M, Amoroso AJ, Harding LP, Pope SJ. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:3407–3411. doi: 10.1039/b923988j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tallec G, Imbert D, Fries PH, Mazzanti M. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:9490–9492. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00994f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lewis DJ, Glover PB, Solomons MC, Pikramenou Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1033–1043. doi: 10.1021/ja109157g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Reisfeld R, Jørgensen CK. Lasers and Excited States or Rare Earths, Springer-Verlag. New York: Berlin Heidelberg; 1977. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen Y, Riedener T, Bray KL. Phys. Rev. B. 2000;61:11460–11471. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kuriki K, Koike Y, Okamoto Y. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:2347–2356. doi: 10.1021/cr010309g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Riis-Johannessen T, Dalla Favera N, Todorova TK, Huber SM, Gagliardi L, Piguet C. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:12702–12718. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dalla Favera N, Kiehne U, Bunzen J, Hyteballe S, Lützen A, Piguet C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:125–128. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Bünzli J-CG. Lanthanide Probes in Life, Chemical and Earth Sciences. chap 7. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989. [Google Scholar]; (b) Parker D, Dickins RS, Puschmann H, Crossland C, Howard JAK. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1977–2010. doi: 10.1021/cr010452+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Comby S, Bünzli J-CG. In: Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Gschneidner KA Jr, Bünzli J-CG, Pecharsky VK, editors. Vol. 37. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2007. pp. 217–470. [Google Scholar]; (d) dos Santos CMG, Harte AJ, Quinn SJ, Gunnlaugsson T. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008;252:2512–2527. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemonnier J-F, Guénée L, Bernardinelli G, Vigier J-F, Bocquet B, Piguet C. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:1252–1265. doi: 10.1021/ic902314f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A drastic anti-cooperative chelate factor of γ = EM1 · EM2/(EM)2 = 10−5.6 (compared with γ = 1 for a statistical behavior) prevents the detection of the usual saturated macrobicyclic triple-stranded helicate [Ln2(L3)3]6+, while the macromonocyclic double-stranded helicate [Ln2(L3)2]6+ suffers from the operation of a very low effective molarity EM1 = 10−7(1) M. Ercolani G, Schiaffino L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1762–1768. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004201.

- 14.(a) Sabbatini N, Guardigli M, Manet I. In: Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Gschneidner KA Jr, Eyring L, editors. Vol. 23. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1996. pp. 69–120. [Google Scholar]; (b) Moore EG, Samuel APS, Raymond KN. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:542–552. doi: 10.1021/ar800211j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Petoud S. Chimia. 2009;63:745–752. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissman SI. J. Chem. Phys. 1942;10:214–217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Beeby A, Faulkner S, Parker DA, Williams JAG. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin 2. 2001:1268–1273. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dossing A. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005:1425–1434. [Google Scholar]; (c) Faulkner S, Pope SJA, Burton-Pye BP. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2005;40:1–35. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ward MD. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010;254:2634–2642. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Malta OL. J. of Luminescence. 1997;71:229–236. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang C-Y, Fu L-M, Wang Y, Zhang J-P, Wong W-T, Ai X-C, Qiao Y-F, Zou B-S, Gui L-L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:5010–5013. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lo W-K, Wong WK, Wong W-Y, Guo J, Yeung K-T, Cheng Y-K, Yang X, Jones RA. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:9315–9325. doi: 10.1021/ic0610177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Perry WS, Pope SJA, Allain C, Coe BJ, Kenwright AM, Faulkner S. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10974–10983. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00877j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ha-Thi M-H, Delaire JA, Michelet V, Leray I. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010;114:3264–3269. doi: 10.1021/jp909402k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Bünzli J-CG, Chauvin A-S, Kim HK, Deiters E, Eliseeva SV. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010;254:2623–2633. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wagenknecht PS, Ford PC. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011;255:591–616. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Since the two [Ln(hfac)3] accepting units are related by symmetry operations in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6], Neumann’s principle implies that the kinetic rate constants for the two bound metals are identical Nye JF. Physical Properties of Crystals. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1985. p. 20. Haussühl S. Kristallphysik. Weinheim: Physic-Verlag; 1983. p. 13.

- 20.All possible internal conversion processes are omitted for clarity, which justifies that the intersystem crossing and energy transfer processes are represented by non-horizontal arrows; Henderson B, Imbusch GF. Optical Spectroscopy of Inorganic Solids. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1989.

- 21.(a) Sabbatini N, Guardigli M, Lehn J-M. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1993;123:201–228. [Google Scholar]; (b) Petoud S, Bünzli J-CG, Glanzman T, Piguet C, Xiang Q, Thummel R. J. Luminesc. 1999;82:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Carnall WT. In: Hanbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Gschneidner KA Jr, Eyring L, editors. Vol 3. Amsterdam New York Oxford: North-Holland Publishing Company; 1979. pp. 171–208. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aebischer A, Gumy F, Bünzli J-CG. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:1346–1353. doi: 10.1039/b816131c. references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Görller-Walrand C, Binnemans K. In: Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Gschneidner KA Jr, Eyring L, editors. Vol. 25. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1998. pp. 101–264. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinhard C, Güdel HU. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:1048–1055. doi: 10.1021/ic0108484. references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Sa GF, Malta OL, de Mello Donega C, Simas AM, Longo RL, Santa-Cruz PA, da Silva EF., Jr Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000;196:165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latva M, Takalo H, Mukkala V-M, Matachescu C, Rodriguez-Ubis JC, Kankare J. J. of Luminescence. 1997;75:149–169. [Google Scholar]; (b) D'Aléo A, Xu J, Moore EG, Jocher CJ, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:6109–6111. doi: 10.1021/ic8003189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Samuel APS, Xu J, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:687–698. doi: 10.1021/ic801904s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shavaleev NM, Eliseeva SV, Scopelliti R, Bünzli J-CG. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3929–3936. doi: 10.1021/ic100129r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Tobita S, Arakawa M, Tanaka I. J. Phys. Chem. 1984;88:2697–2702. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tobita S, Arakawa M, Tanaka I. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:5649–5654. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steemers FJ, Verboom W, Reinhoudt DN, van der Tol EB, Verhoeven JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9408–9414. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yamaguchi Y, Matsubara Y, Ochi T, Wakamiya T, Yoshida Z-I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13867–13869. doi: 10.1021/ja8040493. The conjugation length has no unit and it is proportional to the difference Δµ between the S1 state dipole moment (µ1) and S0 state dipole moment (µ0). Δµ can be estimated by using the Lippert-Mataga equation , in which ν̃a − ν̃f corresponds to the difference in energy between the absorption and fluorescence peaks and a is the molecular radius.

- 30.26°< α < 34° were found in the crystal structure of L3·3CHCl3.12

- 31.Crowther GP, Sundberg RJ, Sarpeshkar AM. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:4657–4663. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iovine PM, Kellett MA, Redmore NP, Therien MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8717–8727. [Google Scholar]

- 33.For L4, H15 appears as a pseudo-triplet because of its scalar coupling with the two fluorine atoms with Clerc T, Pretsch E. Kernresosonanz-Spectroskopie. Frankfurt: Akademische Verlagsgesellshaft; 1973. p. 114.

- 34.Lunazzi L, Mazzanti A, Minzoni M, Anderson JE. Org, Lett. 2005;7:1291–1294. doi: 10.1021/ol050091a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The rate of Einstein spontaneous emission in the dipole approximation is given by where ω is the emission frequency, n is the index of refraction, µ12 is the transition dipole moment, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, ħ is the reduced Planck constant and c is the vacuum speed of light. Einstein A, Physik Z. 1917;18:121. Pais A. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1977;49:925–938. Valeur B. Molecular Fluorescence. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2002.

- 36.Yuasa J, Ohno T, Miyata K, Tsumatori H, Hasegawa Y, Kawai T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9892–9902. doi: 10.1021/ja201984u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meech SR, Phillips DC. J. Photochem. 1983;23:193–217. [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) Evans WJ, Giarikos DG, Johnston MA, Greci MA, Ziller JW. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2002:520–526. [Google Scholar]; (b) Malandrino G, Lo Nigro R, Fragalà IL, Benelli C. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004:500–509. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Binnemans K. In: Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Gschneidner KA Jr, Bünzli JCG, Pecharsky VK, editors. Vol. 35. Amsterdam: Elsevier North Holland; 2005. pp. 107–272. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Escande A, Guénée L, Buchwalder K-L, Piguet C. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:1132–1147. doi: 10.1021/ic801908c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Brown ID, Altermatt D. Acta Cryst B. 1985;41:244–247. [Google Scholar]; (b) Breese NE, O'Keeffe M. Acta Cryst. B. 1991;47:192–197. [Google Scholar]; (c) Brown ID. Acta Cryst B. 1992;48:553–572. [Google Scholar]; (d) Brown ID. The Chemical Bond in Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]; (e) Trzesowska ID, Kruszynski R, Bartczak TJ. Acta Cryst B. 2004;60:174–178. doi: 10.1107/S0108768104002678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Trzesowska A, Kruszynski R, Bartczak TJ. Acta Cryst B. 2005;61:429–434. doi: 10.1107/S0108768105016083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zocchi F. J. Mol. Struct. 2007;825–846:73–78. [Google Scholar]; (h) Brown ID. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:6858–6919. doi: 10.1021/cr900053k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalla Favera N, Guénée L, Bernadinelli G, Piguet C. Dalton Trans. 2009:7625–7638. doi: 10.1039/b905131g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carnall WT, Fields PR, Rajnak K. J. Chem. Phys. 1968;49:4443–4446. [Google Scholar]

- 44.(a) Davydof AS. Theory of Absorption of Light in Molecular Crystals. Kiev: Ukrainian Academy of Sciences; 1951. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kasha M, Oppenheimer M. Theory of Molecular Excitons. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. Inc; 1962. [Google Scholar]; (c) Telfer SG, McLean T, Waterland MR. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:3097–3108. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01226b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.(a) Nakamoto K. J. Phys. Chem. 1960;64:1420–1425. [Google Scholar]; (b) Piguet C, Bocquet B, Müller E, Williams AF. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1989;72:323–337. [Google Scholar]

- 46.The π-delocalized bidentate hfac− counter-anions also possess ligand-centered excited states which may contribute to the global sensitization process in [Ln2(Lk)(hfac)6]. This assumption is demonstrated by the absorption spectrum of the starting metallic complex [Gd(hfac)3(diglyme)] which exhibits an intense absorption band centered at 33060 cm−1 (ε = 33300 M−1·cm−1, Figs 8 and S11) that is assigned to the hfac-centered π→* transitions. Irradiation of [Gd(hfac)3(diglyme)] at ν̄exc = 32790 cm−1 produces both faint fluorescence (E(1ππ*) = 26320 cm−1, Fig. S12a) and weak phosphorescence (E(3ππ*) = 21800 cm−1,τL (P) = 270(20) µs at 293 K, Fig. S12b).

- 47.Eq 11 holds when the intersystem crossing process (ISC) is the only significant additional perturbation of the 1ππ* deactivation pathway produced by the complexation of Gd(III). Torelli S, Imbert D, Cantuel M, Bernardinelli G, Delahaye S, Hauser A, Bünzli J-CG, Piguet C. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:3228–3242. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401158.

- 48.Carnall WT, Fields PR, Rajnak K. J. Chem. Phys. 1968;49:4450–4455. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skoog DA, West DM, Holler FJ, Crouch SR. Fundamentals of Analytical Chemistry. 8th Ed. chapt 3. Brooks Cole; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altomare A, Burla MC, Camalli M, Cascarano G, Giacovazzo C, Guagliardi A, Moliterni G, Polidori G, Spagna R. J. Appl. Cryst. 1999;32:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheldrick GM. SHELXL97 Program for the Solution and Refinement of Crystal Structures. Germany: University of Göttingen; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson CK. ORTEP II; Report ORNL-5138. Tennessee: Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casida ME. In: Recent Developments and Applications of Modern Density Functional Theory. Seminario JM, editor. Amsterdam: Ed, Elsevier; 1996. pp. 391–439. [Google Scholar]

- 54.TURBOMOLE V6.1. University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007. TURBOMOLE GmbH, since 2007. 2009 available from http://www.turbomole.com.

- 55.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.