Abstract

Aqueous humor (AH) exiting the eye via the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm's canal (SC) passes through the deep and intrascleral venous plexus (ISVP) or directly through aqueous veins. The purpose of this study was to visualize the human AH outflow system 360 degrees in three dimensions (3D) during active AH outflow in a virtual casting.

The conventional A Houtflow pathways of 7 donor eyes were imaged with a modified Bioptigen spectral-domain optical coherence tomography system (Bioptigen Inc, USA; SuperLum LTD, Ireland) at a perfusion pressure of 20 mmHg (N=3), and 10 mmHg (N=4). In all eyes, 36 scans (3 equally distributed in each clock hour), each covering a 2 × 3 × 2 mm volume (512 frames, each 512 × 1024 pixels), were obtained. All image data were black/white inverted, and the background subtracted (ImageJ 1.40g, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Contrast was adjusted to isolate the ISVP.

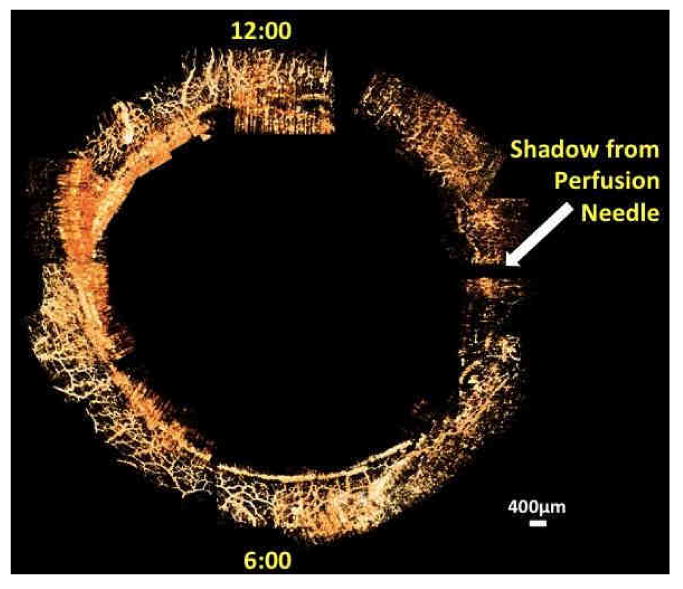

SC, collector channels, the deep and ISVP, and episcleral veins were observed throughout the limbus. Aqueous veins could be observed extending into the episcleral veins. Individual scan ISVP castings were rendered and assembled in 3D space in Amira 4.1 (Visage Imaging Inc. USA). A 360-degree casting of the ISVP was obtained in all perfused eyes. The ISVP tended to be dense and overlapping in the superior and inferior quadrants, and thinner in the lateral quadrants.

The human AH outflow pathway can be imaged using SD-OCT. The more superficial structures of the AH outflow pathway present with sufficient contrast as to be optically isolated and cast in-situ 360 degrees in cadaver eye perfusion models. This approach may be useful as a model in future studies of human AH outflow.

1. Introduction

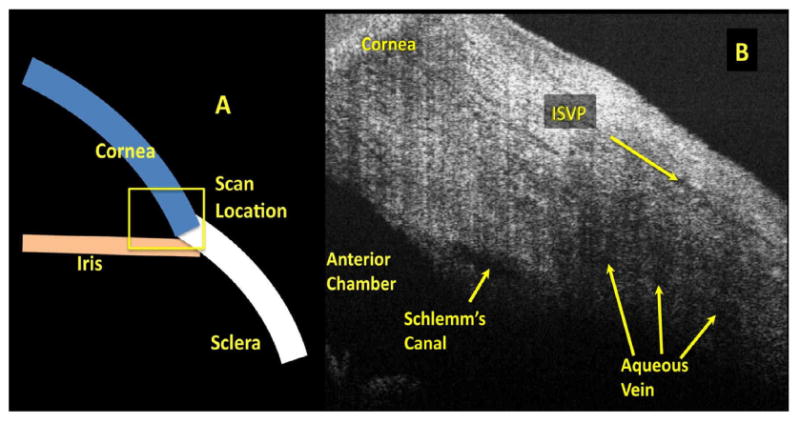

Glaucoma is the second leading cause of irreversible blindness, reducing quality of life and increasing healthcare costs for glaucoma patients. (Kymes et al.; Quigley and Broman, 2006) The greatest risk factor for the presence and progression of glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). (Dielemans et al., 1994; Kahn et al., 1977; Kass et al., 1980; Reynolds, 1977; Sommer, 1989; Vacharat, 1979) IOP is regulated by a balance between the production and drainage of aqueous humor (AH). (Duke-Elder, 1949; Millar and Kaufman, 1995) The majority of AH leaves the eye via the trabecular meshwork in the angle of the anterior chamber and through Schlemm's canal (SC). AH leaves SC either via collector channels to a complex network of aqueous venous plexuses including the deep, midlimbal and perilimbal scleral plexuses, ultimately draining into scleral veins or Ascher's aqueous veins which bypass this tortuous pathway and connect directly from SC to the episcleral veins. (Ascher, 1942; Ashton, 1951, 1952; Ashton and Smith, 1953; van der Merwe and Kidson, 2010) Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and ultrasound imaging of the anterior segment have produced cross-sectional images of the drainage system (Figure 1), but these do not yield sufficient visualization to ascertain the condition or density of the complex three-dimensional (3D) structures of the AH outflow system. (Irshad et al., 2010; Kagemann et al., 2010; Sarunic et al., 2008)

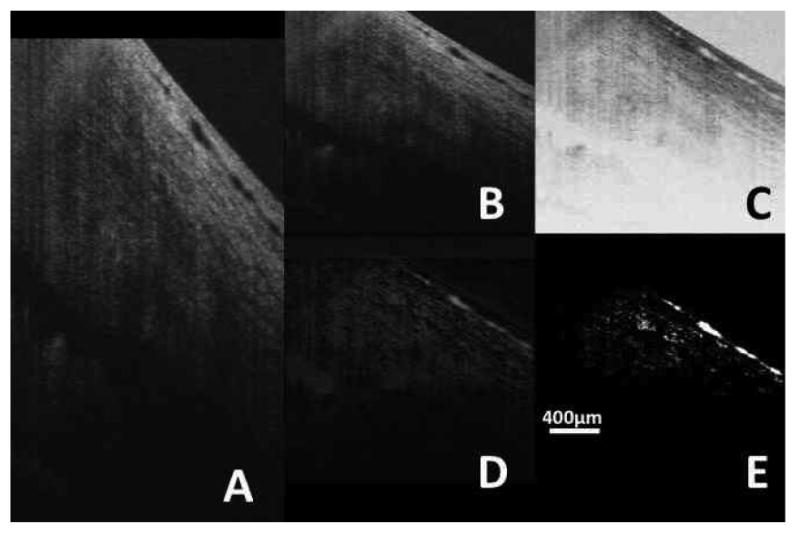

Figure 1.

The anterior chamber angle is scanned by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. (A) Scans contain portions of the iris, cornea, and limbus. Within the scan (B) Schlemm's canal and aqueous veins, and the intrascleral venous plexus (ISVP) are seen.

SD-OCT rapidly quantifies tissue reflectance in three-dimensional (3D) cubes at speeds up to 512,000 axial scans (A-scans) per second. (Rollins et al., 1998; Zhang and Kang) Coupling the high scanning speed with ultrahigh resolution, it is possible to visualize the individual components of the AH outflow system from the anterior chamber throughout the system of aqueous veins in the living human eye. (Kagemann et al., 2010) However, shadows from superficial structures may obscure the deeper structures. (Kagemann et al., 2010) Superficial outflow structures, specifically the intrascleral venous plexus (ISVP) and episcleral veins, are readily visualized by SD-OCT. The purpose of the present work was to develop a method for visualizing the 3D structures of the conventional AH outflow system in human cadaver eyes during perfusion with SD-OCT. After imaging, these same eyes were processed and examined by light microscopy for correlative histology.

2. Materials and Methods

Human cadaver eyes with no history of eye disease, trauma or ocular surgery other than cataract were obtained from the Florida Eye Bank (Miami, FL), and the Center for Organ Recovery and Education (Pittsburgh, PA). The Committee for Oversight of Research Involving the Dead of the University of Pittsburgh approved the study. Consent for the use of all tissues for research was obtained by the individual agency responsible for harvesting and supplying the tissue.

2.1 Tissue Preparation and Perfusion

To prepare for perfusion, seven eyes (Table) were wrapped in saline-soaked gauze, submerged in normal saline, and warmed to 34°C. Eyes were then placed in front of the SD-OCT scanner in a custom-made fixation mount. Throughout the experiment, the eye was irrigated with 40°C saline to prevent dehydration and to minimize cooling. A 27-gauge needle was inserted into the peripheral cornea, with the needle tip passing through the pupil and positioned posterior to the iris and anterior to the lens. This positioning prevented artificial deepening of the anterior chamber during perfusion and artifactual increases in outflow facility. (Ellingsen and Grant, 1971) Barany's mock AH (Barany, 1964) was used to perfuse the eyes. The initial 20 minutes of perfusion was used to establish baseline outflow. The rate of perfusion was determined by recording the weight of the AH in the reservoir in real time, 20 measurements per second. Measurements were recorded by a 4-channel 10-bit digital acquisition system (DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH). Immediately after completion of the perfusion experiments, the eyes were perfusion fixed with 10% formalin buffered solution before further processing for histological evaluation.

Table.

Seven eyes were imaged. The presence of the superficial tissues and anterior chamber pressure varied.

| Eye | Condition | Anterior Chamber Pressure |

|---|---|---|

| 1 and 2 | Intact | 20 mmHg |

| 3 | Conjunctiva and Tenon's Capsule Removed | 20 mmHg |

| 4-7 | Conjunctiva and Tenon's Capsule Removed | 10 mmHg |

Perfusion pressure is the hydrostatic force between the anterior chamber pressure and the pressure within the vessels receiving AH outflow. In this study, a normal episcleral venous pressure of 8 mmHg in living eyes was assumed (Erickson-Lamy et al., 1991). The first two intact eyes were perfused with an anterior chamber pressure of 20 mmHg. Since the episcleral venous pressure in a cadaver eye is approximately 0 mmHg, an anterior chamber pressure of 20 mmHg produced a perfusion pressure equivalent to an IOP of 28 mmHg in a living eye. An anterior chamber pressure of 10 mmHg yielded a perfusion pressure equivalent to an IOP of 18 mmHg in a living eye.

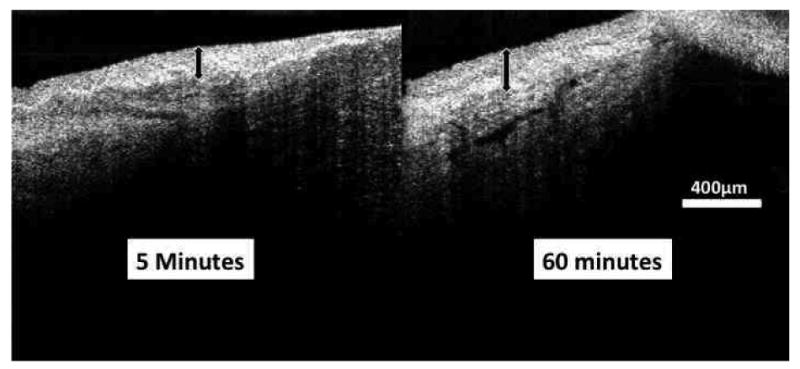

We previously established the ability to image the structures of the AH outflow system throughout. (Kagemann et al., 2010) In the cadaver model, there is no active circulatory system present to remove AH expelled from the outflow system. We found that fluid gradually accumulates in the conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule when that tissue was left intact on the globe (Figure 2), causing shadows obscuring visualization of outflow structures. Therefore, we found that cadaver eyes require the removal of these layers prior to perfusion to produce images of equal quality to those obtained in unperturbed living eyes. The conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule were dissected in all but the first pair of eyes.

Figure 2.

A cross-sectional spectral domain optical coherence tomography scan of the region of the limbus in a perfused eye reveals that the conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule engorge with AH. A section of the limbus is seen after being perfused for 5 minutes (left) and 60 minutes (right) showing thickening of the superficial tissue layers (black arrows).

Four eyes were perfused and imaged at 10 mmHg, and then perfusion fixed at 10 mmHg for histology. One of these eyes was first imaged at a perfusion pressure of 0 mmHg. One eye was perfused and imaged at 20 mmHg. After imaging, it was perfusion fixed at 20 mmHg.

2.2 SD-OCT Imaging

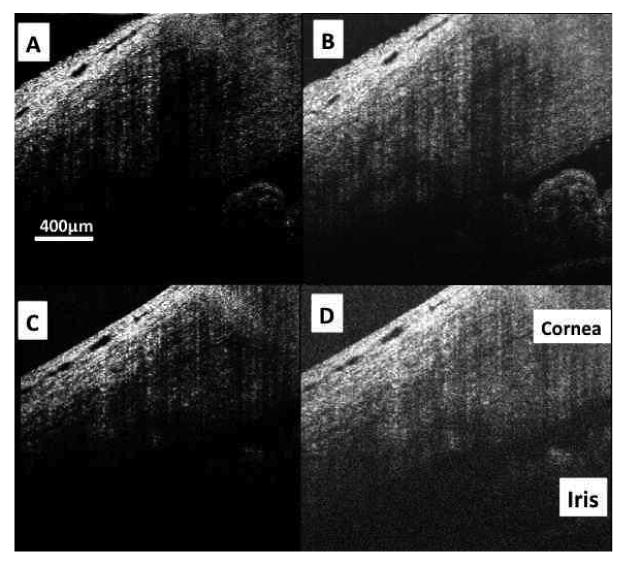

An SD-OCT optics engine (Bioptigen, Research Triangle, NC) was coupled with a high band width superluminescent diode array (870nm center wavelength, 200 nm bandwidth; model Q870, Superlum Ltd, Dublin, Ireland). This configuration provided a theoretical axial resolution of 1.3 μm in tissue. The optics engine allows the user to specify any number of A-scans per frame, and any number of frames, limited only by system memory. It also allows the user to specify any number of sequential a-scans to be acquired in a single location during a raster scan for the purpose of averaging and Doppler assessment; also limited only by system memory. Two scan protocols were created; one optimized for the acquisition of 3D data (the “volume” protocol) and one optimized for visualization of individual frames (the “2D slice” protocol). Each eye was scanned twice at the limbus, first with a protocol optimized for 3D volumes, and the second with a protocol optimized for visualization of 2D slices. Each set of images was comprised of 36 individual radial scansets; each clock hour imaged at its center, and offset to the left and right. The angle of each set of clock hour scans was set so that the center clock hour scan was on a radial line from the center of the pupil (i.e. the 9 o'clock scan was at 0°, the 10 o'clock scan at 30°, the 11 o'clock scan at 60°, etc.). The 3D volume scan protocol was limited by system memory, and consisted of 512 × 512 axial scans (A-scans) probing a 2 × 3 mm (radial × transverse) area of tissue (Figure 3 C and D).

Figure 3.

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography images would normally be displayed with a low level of brightness. (A) In the case of highly averaged image data (700 A-scans in this frame; each A-scan the average of 18 sequentially acquired A-scans), brightness can be increased (B) allowing visualization of deep low signal structures such as the iris, angle, trabecular meshwork, and endothelial/Descemet's complex without compromising due to visible noise. SDOCT images obtained without averaging (512 A-scans, each presented without averaging) and displayed with a low level of brightness (C) have an appearance similar to those obtained with averaging at the same noise suppression level. But, increasing brightness reveals the noise masking the deep layers where the signal is low (D).

This scan protocol only moved the 20 μm diameter SDOCT beam 9 μm between A-scans, thus including a single tissue volume in multiple adjacent samples (oversampling). Acquiring oversampled SDOCT data allowed post-process averaging. The 2D slice protocol consisted of 700 × 20 A-scans probing the same sized (2 × 3 mm) area of tissue. Each A-scan of the 2D slice imaging protocol was repeated 18 times, and the average of those 18 scans recorded (Figure 3 A and B). This method was previously described in detail. (Cense et al., 2006)

2.3 Correlative Light Microscopy Imaging

After imaging using SD-OCT, two eyes were perfusion-fixed at 10 mmHg and one eye was perfusion fixed at 20 mmHg. Following perfusion fixation, the three eyes were placed in 10% formalin buffered solution overnight and then transferred to PBS. The anterior chamber of each eye was cut radially into 12 pieces (1 clock hour each) and processed for light microscopic examination. The sections were post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide (Fisher Scientific, NJ) for 2 hours, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanols, and embedded in Epon-Araldite (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). 3 μm sections were cut (4 blocks each eye at 3, 6, 9 and 12 o'clock) and stained with 1% Toluidine Blue (Fisher Scientific, NJ). Light micrographs were taken at an original magnification of 4× and 10×. The histological images were compared with SD-OCT images from the same locations.

2.4 SD-OCT Image Processing

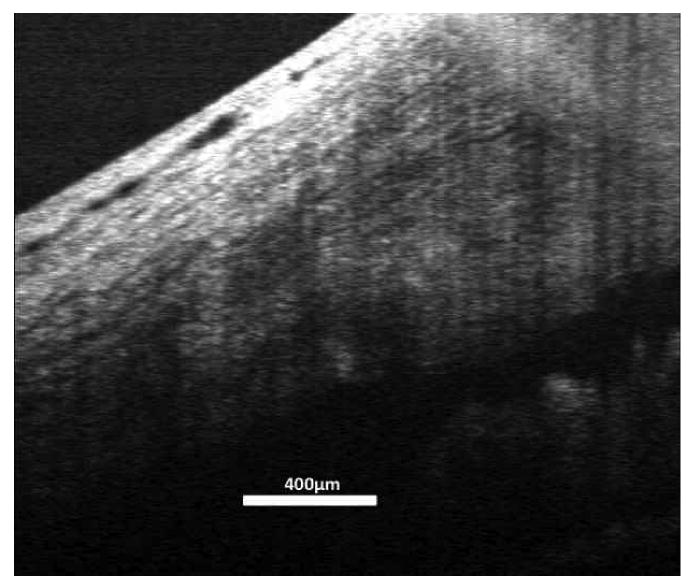

Raw SD-OCT scan data are analyzed by histogram. The 75% of SD-OCT data with the lowest reflectance values are set to 0 when displayed. (Stein et al., 2006) This approach is effective for the subjective improvement of visualization of highly reflective structures, but if the structures are in a region of low signal strength, they will not be displayed. In the slice image set, averaging during image acquisition improved visualization of structures with low reflectance. Increasing image brightness in highly averaged image data further improves visualization of the deep outflow structures (Figure 3). However, in the volume image data set, raw data acquired from deep outflow structures were difficult to visualize. Increasing image brightness increases visualization of deep low-reflectance structures, but also increases the appearance of speckle noise, obscuring structure details (Figure 3). This can be overcome by signal averaging. The volume image protocol spatially oversamples the tissue, allowing averaging with minimal loss of structural information. A floating 5 × 5 pixel transverse kernel, consisting of 5 pixels in each of 5 adjacent frames, was used to produce an average dataset, using customized software of our own design. Visualization of deep layers within the post-processing averaged volume dataset was comparable to that of the slice data (Figures 4 and 3B).

Figure 4.

Averaging the 3D volume protocol scan data improved visualization of the deep structures in the angle to a level similar to that of the 2D slice protocol image shown in figure 3.

Further image processing was performed using ImageJ 64 (ImageJ 1.40g, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Images were resampled to provide a 1:1:1 voxel aspect ratio in three dimensions; from 512 × 512 × 1024 (Figure 5A) to 342 × 512 × 342 (Figure 5B) for each 2 × 3 × 2 mm volume. Images were then inverted so that the black collector channels appeared as white structures (Figure 5C). The ImageJ “subtract background” filter was applied with a 30 pixel kernel and without further averaging (Figure 5D). Contrast was then adjusted to isolate the collector channels, (Figure 5E) and the volumes rendered using the ImageJ 64 3D viewer plug-in (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

The averaged image stack has a spatial resolution of 512 × 512 × 1024 voxels encompassing a physical volume of 2 × 3 × 2 mm. (A) A single averaged frame. (B) The data were resampled to yield a 1:1:1 aspect ratio. The resampled data were inverted (C) and background was subtracted. (D) Contrast was than adjusted to isolate the structures of interest (E).

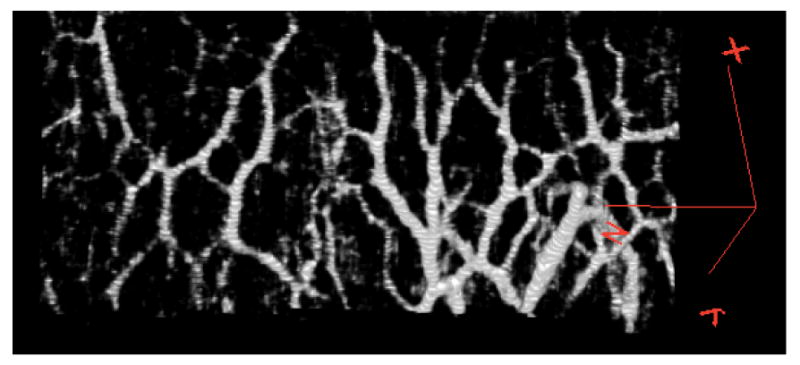

Figure 6.

The isolated intrascleral venous plexus image data can be rendered in 3D to visualize the ISVP during active outflow. This is one of 36 circumferential scans of the limbus, showing a portion of the venous network. The red marker on the right indicates the X, Y, and Z axes of the 3D space, with the interrogating SDOCT beam projecting down the Z axis, and raster scanning the X-Y plane.

Individual stacks were opened in Amira 4.1 (Visage Imaging Inc., San Diego, CA) and rendered in 3D space with the Voltex module (2D texture, rendering down sample 3,3,3). Stacks were manually assembled in 3D space by overlaying aqueous veins and structures visible in adjacent scans. The volume scan protocol provided a large degree of overlap; most individual aqueous veins were contained in two images, and occasionally in three.

3. Results

Outflow structures from the trabecular meshwork through the CC could be visualized throughout the limbus. The slice imaging protocol provided better visualization of outflow structures in cross-section, likely due to the combined effects of spatial oversampling (700 a-scans per frame) and aggressive averaging (18 sequentially acquired a-scans averaged to produce each displayed a-scan; Figure 3B). Unfortunately, scanner memory restrictions limit the number of frames that can be acquired using this protocol. The low number of frames makes the slice protocol unsuitable for enface imaging (Figure 3D) or 3D reconstructions. The volume imaging protocol provides excellent enface images, and post-processing averaging allows the recovery of detail within deep structures (Figure4, right). The sampling density of the volume protocol also allows high-resolution 3D reconstruction of the outflow system within individual scans (Figure 6).

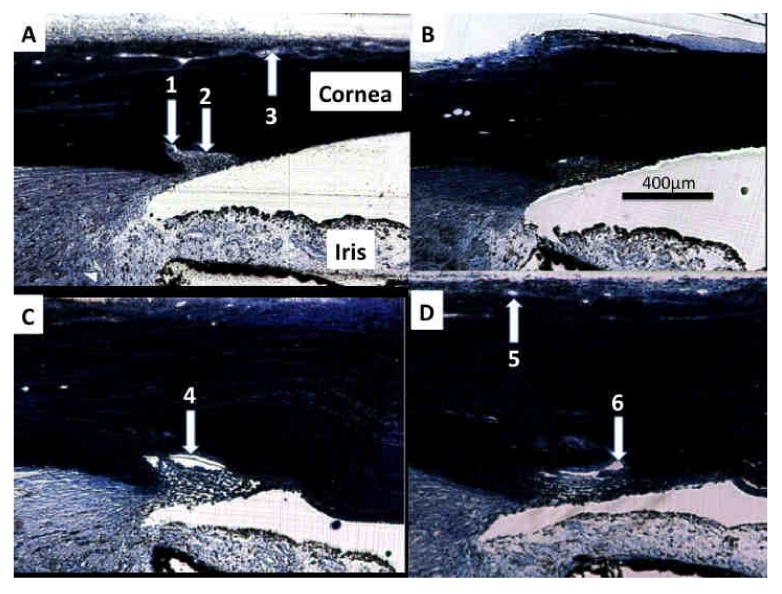

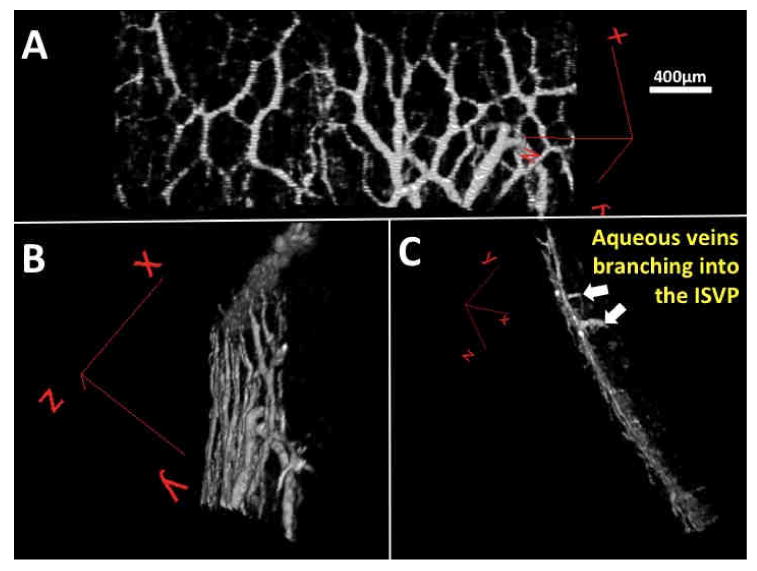

It has been shown that exposure to elevated IOP may lead to closure of SC as the TM pushes and compresses the inner wall towards the outer wall. (Battista et al., 2008) At 20 mmHg perfusion pressure, SD-OCT revealed very few locations with a visible patent SC. This finding was confirmed by histology (Figure 7). Collector channel ostia and patent aqueous venous structures were observed by SD-OCT and confirmed by histology (Figure 7). At 10 mmHg, SC was not compressed (Figure 7). Smaller scleral veins running from the ISVP down toward the deep scleral venous plexus were frequently observed in individual frames of the 3D datasets, but seldom achieved sufficient contrast, relative to background tissue, to be observed in the 3D reconstructions. Occasionally, a large aqueous vein could be observed, but only when isolated from other branches of the ISVP. Figure 8 shows the front and side views of a scan obtained from one eye. Note the vessels that penetrate perpendicular to the ISVP.

Figure 7.

(A) A histological section from the 6:00 position in an eye perfused at 20 mmHg presents with an open ostium (1) despite the anterior surface of the trabecular meshwork compressing Schlemm's canal (SC, 2). Vessels of the intrascleral venous plexus (ISVP) are visible (3). (B) The same eye at the 9:00 position also presents with a compressed SC, but no visible ISVP vasculature. (C) A different eye perfused at only 10 mmHg presents with a large open SC at the 9:00 position (4). (D) At the 12:00 position, SC ISVP vessels are present (5), as are SC and open ostia (6).

Figure 8.

To reveal the posterior surface of the vascular network a single slice is rotated and seen from three perspectives. Aqueous veins could be observed penetrating the intrascleral venous plexus from proximal structures in the aqueous humor outflow system. (A) A virtual casting from the 6:00 position in an eye perfused at 20 mmHg can be rotated (B) to expose the posterior surface (C) revealing two aqueous veins. (white arrows)

After individually processing the 36 scans of the limbus of the structural imaging protocol a composite casting of the collector channels of the AH outflow system was rendered (Figure 9) The densest arrays of aqueous veins within the ISVP were observed near the 6 and 12 o'clock positions.

Figure 9.

36 circumferential limbal scans were processed and assembled manually in 3D space to yield a full casting of the episcleral and intrascleral venous plexus throughout the limbus in-situ during active perfusion.

4. Discussion

We present the first virtual casting of superficial venous plexus of AH outflow system. The imaging process is completely non-contact and requiring no dyes or contrast agents. In living human eyes, the imaging process would be completely non-invasive. In the cadaver model, the conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule must be removed to produce images of similar quality as those produced in living eyes. Virtual casting was made possible by the high degree of contrast between the superficial venous plexus of AH outflow system, including aqueous veins, and surrounding tissues achieved by aggressive post-processing averaging.

There was good agreement between features observed in the SD-OCT 2D scans and the corresponding histological sections (Figure 7). This included the appearance of SC under different perfusion pressure conditions as well as the presence or absence of the open superficial vessels comprising the ISVP.

A cadaver eye, as used in this experiment, differs from a living eye. Specifically the cadaver eye lacks circulatory-related pulsations in IOP and blinking which each may contribute force to outflow. (Johnstone, 2004) The change from a pulsatile to non-pulsatile environment may alter the conditions dictating the preferential location of outflow within the eye. There is also a lack of pulsatility in the vessels receiving AH. In the living eye, scleral veins receive AH in an environment of transient pressure waves. In the cadaver eye, AH arrived in vessels with no backpressure. During perfusion, the vessels were observed to fill with AH, resulting in some small constant backpressure. Combined with gravity, it is possible that the preferential outflow path in a cadaver model differs significantly from that of a living eye. But, if gravity were the only influence, we would have expected full aqueous vessels in the inferior with a gradual diminution of the casting until it appeared empty in the superior. The present study found the fullest ISVP castings in the superior and inferior quadrants. Previously, we reported that in living human eyes, SC near CC ostia appeared to be larger in the nasal quadrant of the limbus. (Kagemann et al., 2010)

Our initial data indicated that the conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule needed to be removed before perfusion in order to image the deep layers of the limbus with quality equal to that obtained in living human eyes and avoid distention of the outer tissue layers as they filled with AH. It is likely that the superficial-most vessels of the outflow system were also removed. In the remaining tissues, it is impossible to determine what percentage, if any, of the virtual casting consisted of ISVP or the midlimbal intrascleral plexus, or some combination therein. Interconnectivity was observed within the vascular network. The lack of blood flow supports the contention that the casting is of active AH outflow, though the identity of the actual observed vessels, whether aqueous vessels or venules, can only be inferred by their location and connectivity. We are confident that some portion of the castings consisted of aqueous veins, as those portions were observed to penetrate into the limbus (Figure 8) and could be seen in individual frames extending directly to SC ostia. Nevertheless, since there was no active cardiac circulation in the imaged tissues, all passages captured in the casting were open and connected because they were carrying mock AH as part of the outflow process.

It would be desirable to have a complete casting of the outflow system, down to SC. A recent study produced virtual castings of the outflow system at the level of SC in sections of a stained eye using micro CT. (Hann et al.) In the present method, only the superficial venous plexus or occasional large penetrating aqueous veins could be optically isolated from surrounding tissues, though this was accomplished non-invasively and without introduction of any contrast agents. It is possible that a more sophisticated image processing technique could include more structures in the casting. Specifically, imposing a connectivity requirement for inclusion in the casting might reduce the use of contrast for isolation and allow the smaller structures to be included despite weak signal levels.

As we continue to develop the ability to image AH outflow as it occurs, our goal is to be able to detect deficits associated with disease, and determine the effects of glaucoma medications and surgical interventions on outflow and the associated structures. Currently the two largest impediments to clinical implementation are penetration and eye movements. The structural and functional scan protocols used in this study required approximately 10 seconds each, with a data acquisition rate of 28,000 a-scans per second. This is far too slow to obtain useful data in human eyes, as eye movement artifacts are readily visible in 2 second scans obtained with commercially available SD-OCT's. However, “cutting edge” SD-OCT systems have achieved a scan rate of 512,000 a-scans per second, which would reduce the scan time to 0.5 seconds. (Zhang and Kang) Longer wavelength systems may overcome current limitations in penetration, but despite the limits of the 870nm centered system, using aggressive averaging we are able to resolve the structures of the angle and conventional outflow system (Figures 3 and 4).

Clinical and research use will require the development of meaningful parameters that quantify outflow structures. The outflow structures are too numerous and dense, and with marked regional variation, to arbitrarily choose individual CC's to represent outflow. Assessment of the outflow venous network will involve an automated quantification of aqueous vein density and the distribution of vein sizes. Quantification of the number of branch points may also have some clinical meaning. Ultimate utility will depend on determination of how each of these potential parameters are affected by the presence of glaucoma. There is an unmet need for development of outflow casting analysis software.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we present the first virtual casting of AH outflow structures obtained non-invasively in-situ ex-vivo. Continued development of this technique may lead to clinically useful direct assessment of outflow in patients with glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported in part by National Institute of Health contracts R01-EY13178, and P30-EY08098 (Bethesda, MD), the National Glaucoma Research Program of the American Health Assistance Foundation, the Eye and Ear Foundation (Pittsburgh, PA), and unrestricted grants from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Wollstein received research funding from Carl Zeiss Meditec and Optovue. Drs. Wollstein, Ishikawa and Schuman have intellectual property licensed by the University of Pittsburgh to Bioptigen. Dr. Schuman received royalties for intellectual property licensed by Massachusetts Institute of Technology to Carl Zeiss Meditec.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ascher KW. Aqueous veins: physiologic importance of visible elimination of intraocular fluid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1942;25 doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton N. Anatomical study of Schlemm's canal and aqueous veins by means of neoprene casts. Part I. Aqueous veins. Br J Ophthalmol. 1951;35:291–303. doi: 10.1136/bjo.35.5.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton N. Anatomical study of Schlemm's canal and aqueous veins by means of neoprene casts. II. Aqueous veins. Br J Ophthalmol. 1952;36:265–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.36.5.265. contd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton N, Smith R. Anatomical study of Schlemm's canal and aqueous veins by means of neoprene casts. III. Arterial relations of Schlemm's canal. Br J Ophthalmol. 1953;37:577–586. doi: 10.1136/bjo.37.10.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barany EH. Simultaneous Measurement of Changing Intraocular Pressure and Outflow Facility in the Vervet Monkey by Constant Pressure Infusion. Invest Ophthalmol. 1964;3:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista SA, Lu Z, Hofmann S, Freddo T, Overby DR, Gong H. Reduction of the available area for aqueous humor outflow and increase in meshwork herniations into collector channels following acute IOP elevation in bovine eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5346–5352. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cense B, Chen TC, Nassif N, Pierce MC, Yun SH, Park BH, Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, de Boer JF. Ultra-high speed and ultra-high resolution spectral-domain optical coherence tomography and optical Doppler tomography in ophthalmology. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2006:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dielemans I, Vingerling JR, Wolfs RC, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, de Jong PT. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in a population-based study in The Netherlands. The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1851–1855. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke-Elder S. The physiology of the intraocular fluids and its clinical significance. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1949;54:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsen BA, Grant WM. The relationship of pressure and aqueous outflow in enucleated human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol. 1971;10:430–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson-Lamy K, Rohen JW, Grant WM. Outflow facility studies in the perfused human ocular anterior segment. Exp Eye Res. 1991;52:723–731. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann CR, Bentley MD, Vercnocke A, Ritman EL, Fautsch MP. Imaging the human aqueous humor outflow pathway in human eyes by three-dimensional micro-computed tomography (3D micro-CT) Exp Eye Res. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad FA, Mayfield MS, Zurakowski D, Ayyala RS. Variation in Schlemm's canal diameter and location by ultrasound biomicroscopy. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:916–920. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone MA. The aqueous outflow system as a mechanical pump: evidence from examination of tissue and aqueous movement in human and non-human primates. J Glaucoma. 2004;13:421–438. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000131757.63542.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagemann L, Wollstein G, Ishikawa H, Bilonick RA, Brennen PM, Folio LS, Gabriele ML, Schuman JS. Identification and assessment of Schlemm's canal by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4054–4059. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn HA, Leibowitz HM, Ganley JP, Kini MM, Colton T, Nickerson RS, Dawber TR. The Framingham Eye Study. I. Outline and major prevalence findings. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106:17–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass MA, Hart WM, Jr, Gordon M, Miller JP. Risk factors favoring the development of glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;25:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(80)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kymes SM, Plotzke MR, Li JZ, Nichol MB, Wu J, Fain J. The increased cost of medical services for people diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma: a decision analytic approach. Am J Ophthalmol. 150:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar C, Kaufman P. Aqueous humor: secretion and dynamics. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, editors. Duane's foundations of clinical ophthalmology. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DC. Relative risk factors in chronic open-angle glaucoma: an epidemiological study. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1977;54:116–120. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197702000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins A, Yazdanfar S, Kulkarni M, Ung-Arunyawee R, Izatt J. In vivo video rate optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 1998;3:219–229. doi: 10.1364/oe.3.000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarunic MV, Asrani S, Izatt JA. Imaging the ocular anterior segment with real-time, full-range Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:537–542. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer A. Intraocular pressure and glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:186–188. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DM, Ishikawa H, Hariprasad R, Wollstein G, Noecker RJ, Fujimoto JG, Schuman JS. A new quality assessment parameter for optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:186–190. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.059824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacharat N. Risk factors in glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1979;19:157–197. doi: 10.1097/00004397-197901910-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe EL, Kidson SH. Advances in imaging the blood and aqueous vessels of the ocular limbus. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Kang JU. Real-time 4D signal processing and visualization using graphics processing unit on a regular nonlinear-k Fourier-domain OCT system. Opt Express. 18:11772–11784. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.011772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]