Abstract

This is the first study to examine maternal predictors of comorbid trajectories of cigarette smoking and marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood. Participants (N=806) are part of an on-going longitudinal psychosocial study of mothers and their children. Mothers were administered structured interviews when participants were adolescents, and participants were interviewed at six time waves, from adolescence to adulthood. Mothers and participants independently reported on their relationship when participants were X̄ age 14.1 years. At each time wave, participants answered questions about their cigarette and marijuana use since the previous wave to the present. Latent growth mixture modeling determined the participants’ membership in trajectory groups of comorbid smoking and marijuana use, from X̄ ages 14.1 to 36.6 years. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association of maternal factors (when participants were adolescents) with participants’ comorbid trajectory group membership. Findings showed that most maternal risk (e.g., mother-child conflict, maternal smoking) and protective (e.g., maternal affection) factors predicted participants’ membership in trajectory groups of greater and lesser comorbid substance use, respectively. Clinical implications include the importance of addressing the mother-child relationship in prevention and treatment programs for comorbid cigarette smoking and marijuana use.

Keywords: Comorbid trajectories, Comorbid tobacco and marijuana use, Maternal risk and protective factors, Maternal smoking, Longitudinal substance use

1. Introduction

There have been a number of important studies (typically, from adolescence into young adulthood) on trajectories of tobacco use (e.g., Chassin, Presson, Pitts, & Sherman, 2000; Orlando, Tucker, Ellickson, & Klein, 2004), and somewhat fewer investigations on marijuana use trajectories (e.g., Windle & Weisner, 2004). Little research, however, has examined the comorbid trajectories of both cigarette smoking and marijuana use. Jackson, Sher, & Schulenberg (2008) discerned seven comorbid trajectory groups of tobacco and marijuana use (including abstainers) from late adolescence to young adulthood, and identified psychosocial factors, such as delinquency, which were related to trajectory group membership. Brook, Lee, Finch, & Brown (2010) found that greater emotional and behavioral problems, as well as deviant peer affiliations, were each associated with the heaviest comorbid cigarette and marijuana use group, among African Americans and Puerto Ricans.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the maternal predictors of comorbid smoking and marijuana use trajectories across several developmental periods (i.e., adolescence to adulthood). Our theoretical framework is based on Family Interactional Theory (FIT; Brook, Brook, Gordon, Whiteman, & Cohen, 1990), which posits that the parent-child relationship is the nexus of several interrelated domains (e.g., family, peer group) that may affect child outcomes, such as substance use. According to FIT, these domains are linked with the child’s behavior via social modeling, parent-child attachment, and the child’s identification with parental values and behaviors as a result of this attachment. The child’s social modeling and introjection of parental pro-social affect and behavior, in turn, will facilitate the child’s own emotional control, and the development of conventional personal attributes, as well as foster the child’s affiliation with non-substance-using peers. Here, we extend the FIT paradigm to an adult cohort.

The research literature has established the important etiological role of family factors, and especially, the parent-child relationship, in both cigarette smoking and marijuana use during adolescence and young adulthood (e.g., Gutman, Eccles, Peck, & Malanchuk, 2011; Marti, Stice, & Springer, 2010). For example, Butters (2002) demonstrated that poor parent-child relationships predicted marijuana use and marijuana use problems among adolescents.

Cigarette smoking and marijuana use often co-occur. Degenhardt, Hall, & Lynskey (2001), for instance, found that regular tobacco use was associated with marijuana use, abuse, and dependence among adults. Much less is known, however, about the long-term patterns of comorbid smoking and marijuana use or, moreover, their predictors. Based on previous research on trajectories of substance use (e.g., Ellickson, Martino, & Collins, 2004), we hypothesized the following 5–6 comorbid cigarette smoking and marijuana use trajectory groups: a) chronic heavy, b) moderate, c) late-onset, d) mixed groups (in which one substance was used more heavily than the other over time), e) non- or experimental users, and possibly, f) a group that matured out of both cigarette and marijuana use. We further hypothesized that the quality of several aspects of the mother-child relationship when participants were adolescents, as well as maternal smoking, would serve as risk (e.g., maternal-child conflict) or protective (e.g., maternal affection) factors for trajectory group membership.

Our specific hypotheses were: 1) Heavy cigarette smokers/heavy marijuana users would score lower on the measures of mother-child attachment (e.g., less maternal affection), and higher on maternal smoking, than the other comorbid trajectory groups; 2) Heavy cigarette smokers who engaged in occasional or moderate marijuana use would report a weaker attachment relationship with their mother, and have mother’s with higher smoking scores, than the non- or experimental cigarette smokers/marijuana users; 3) Occasional cigarette smokers who were moderate or heavy marijuana users would have a weaker mother-child attachment relationship (e.g., greater conflict), and more maternal smoking, than non- or experimental smokers/marijuana users; and 4) Late-starting cigarette and marijuana users would have less mutual attachment with their mothers, and more maternal smoking, than the non- or experimental users.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Participants are part of an on-going psychosocial study of a community cohort of mothers and their children, begun in 1975. The original sample was representative of families residing in the northeast U.S., at that time, with respect to gender, structure, income, and parental education. The mothers’ reports used in the present analysis were obtained at Time 2 (T2; 1983). Interviews with participants were conducted in 1983 (T2, N=756; X̄ age=14.1 years, SD=2.8), 1985–1986 (T3, N=739; X̄ age=16.3, SD=2.8), 1992 (T4, N=750; X̄ age=22.3, SD=2.8), 1997 (T5, N=749; X̄ age=31.9, SD=2.8), 2002 (T6, N=673; X̄ age=31.9, SD=2.8), and 2005–2006 (T7, N=607; X̄ age=36.6, SD=2.8). Participants in the present study (N=806) were interviewed at least twice from 1983 onwards.

Interviews were administered in private by extensively trained interviewers. Written informed consent (and HIPAA authorization, as of April 2002) were obtained from the participants and their mothers at each time wave. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York University School of Medicine. Additional details regarding the study methodology are available in prior publications (e.g., Brook, Whiteman, Gordon, & Cohen, 1986).

2.2 Measures

Measures of the quantities and frequencies of cigarette smoking and marijuana use (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 2006) were used at each wave (T2-T7) to assess changes in the use of both substances since the previous wave. The response range for the cigarette smoking measure at each wave was: none (0), less than daily (1), 1–5 cigarettes a day (2), about half a pack a day (3), about a pack a day (4), and about 1.5 packs a day or more (5). The marijuana use measure at each time wave was coded as: none (0), a few times a year or less (1), once a month (2), several times a month (3), once a week (4), several times a week (5), and every day (6).

Maternal childrearing behaviors, and maternal smoking, were assessed at T2. The six scales that assessed maternal factors included: maternal identification (maternal admiration, emulation, and similarity; Brook et al., 1990), maternal affection (Schaefer, 1965), maternal satisfaction with the child (Brook et al., 1990), the child’s resistance to maternal control (a measure of mother-child conflict; Schaefer & Finkelstein, 1975), maternal rejection (Avgar, Bronfenbrenner, & Henderson, 1977), and maternal smoking (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 2006). The Cronbach’s alphas for the maternal scales ranged from 0.72 to 0.91, and were satisfactory.

2.3 Analysis

We used Mplus software (Muthén, & Muthén, 2010) to identify the comorbid developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking and marijuana use (N=806). The minimum Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used to determine the number of trajectory groups. The observed trajectories for a group were the averages of cigarette smoking and marijuana use at each time point for the participants assigned to the group.

We then performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to examine the associations between each of the maternal risk and protective factors and trajectory group membership. Gender, age, family income, and parental educational level at T2 were controlled for. The independent variable (e.g., maternal affection) was standardized.

3. Results

3.1

A five-group model was selected, based on the BIC criterion. For each group, the mean Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) of the participants who were assigned to the corresponding group ranged from 90% to 94%, which indicates a good classification.

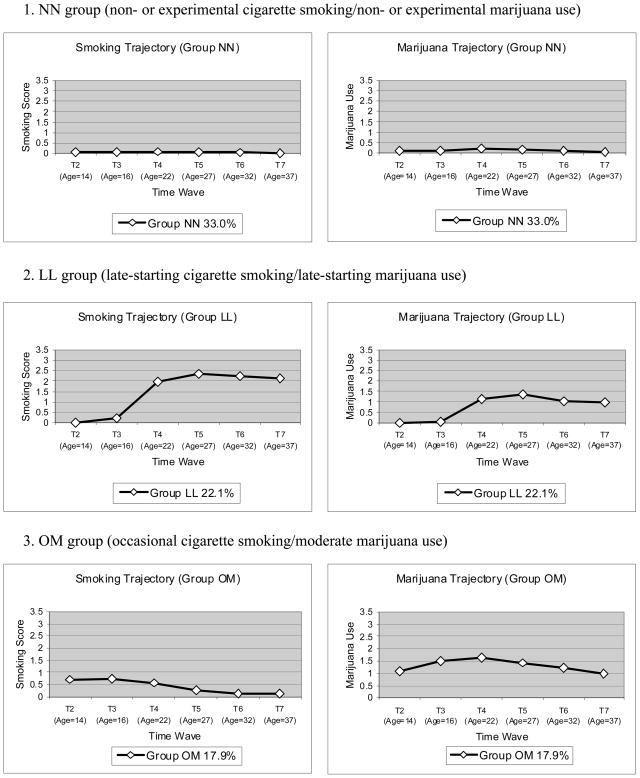

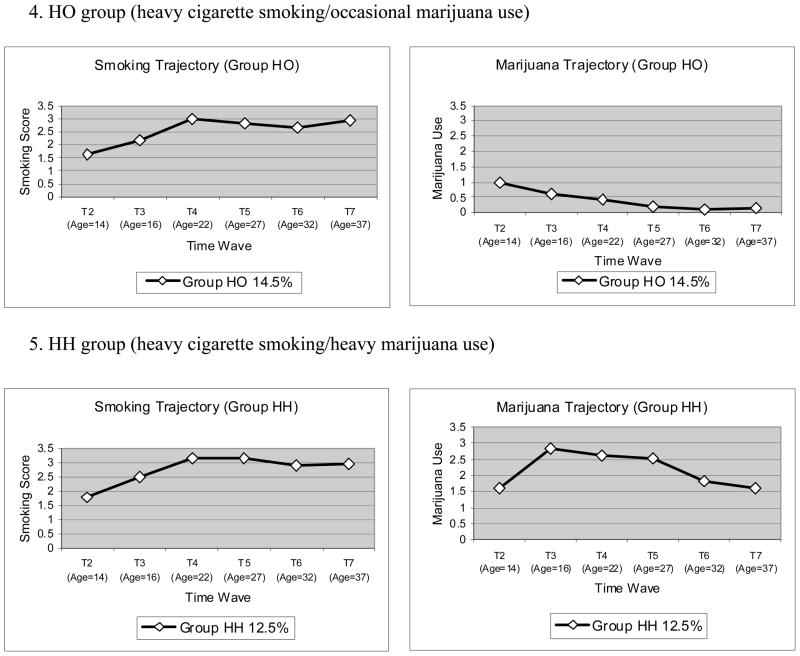

The five comorbid trajectory groups were named: 1) non- or experimental cigarette smoking/non- or experimental marijuana use (NN, 33%), 2) late-starting cigarette smoking/late-starting marijuana use (LL, 22.1%), 3) occasional cigarette smoking/moderate marijuana use (OM, 17.9%), 4) heavy continuous cigarette smoking/occasional marijuana use (HO, 14.5%), and 5) heavy continuous cigarette smoking/heavy continuous marijuana use (HH, 12.5%). (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Comorbid Trajectories of Cigarette Smoking and Marijuana Use

Notes:

- The cigarette smoking measure at each time point was: 0=none, 1=less than daily, 2=1–5 cigarettes a day, 3=about half a pack a day, 4=about a pack a day, and 5=about 1.5 packs a day or more;

- The marijuana use measure at each time point was: 0=none, 1=a few times a year or less, 2=once a month, 3=several times a month, 4=once a week, 5=several times a week, and 6=every day.

- NN group: mean BPP=94%, min. BPP=49%, max. BPP=100%; LL group: mean BPP=92%, min. BPP=28%, max. BPP=100%; OM group: mean BPP=91%, min. BPP=48%, max. BPP=100%; HO group: mean BPP=91%, min. BPP=49%, max. BPP=100%; HH group: mean BPP=90%, min BPP=45%, max BPP=100%.

3.2

Table 1 presents the results from the multivariate logistic regression analyses for comorbid trajectory group memberships. All maternal risk and protective factors were associated with an increased and a decreased likelihood, respectively, of being in the HH group compared with the NN group (Table 1, columns 1–4). Similar, but relatively weaker and fewer, findings were obtained when the HH users were compared with the other trajectory groups. Resistance to maternal control consistently differentiated the HH users from the other groups. Next, as shown in Table 1, columns 5–7, most maternal risk and protective factors predicted membership in the OM trajectory group, with less maternal identification distinguishing the OM group from the NNs, LLs, and HOs. Third, protective factors, such as maternal satisfaction, were associated with a decreased likelihood of membership in the HO group as compared with the NN or LL groups (columns 8–9). Fourth, no factors significantly differentiated between the LL and NN user groups (column 10). (See Table 1.)

Table 1.

Logistic regression of risk and protective maternal factors associated with the comorbid trajectories of cigarette smoking and marijuana use over time. Adjusted odds ratio (A.O.R.) adjusted for gender, age, family income, and parental educational level.

| Column # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables: | HH vs. NN A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

HH vs. LL A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

HH vs. HO A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

HH vs. OM A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

OM vs. NN A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

OM vs. LL A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

OM vs. HO A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

HO vs. NN A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

HO vs. LL A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

LL vs. NN A.O.R. (95% C.I.) |

| Maternal Identification | .62*** (.49–.79) | .61*** (.45–.81) | .64** (.47–.89) | N.S. | .66*** (.52–.84) | .69** (.52–.92) | .63** (.46–.87) | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. |

| Maternal Affection | .70** (.55–.87) | .67** (.50–.90) | N.S. | N.S. | .74** (.60–.92) | .70a (.57–1.00) | N.S. | .73* (.57–.93) | .68* (.49–.94) | N.S. |

| Maternal Satisfaction | .45** (.27–.76) | N.S. | N.S. | .63a (.37–1.06) | N.S. | N.S. | 2.15** (1.24–3.75) | .33*** (.20–.56) | .34** (.18–67) | N.S. |

| Resistance to Maternal Control | 1.81*** (1.32–2.49) | 2.03** (1.31–3.15) | 1.54* (1.07–2.21) | 1.55* (1.09–2.20) | 1.39a (0.98–1.96) | 1.65* (1.05–2.60) | N.S. | N.S. | 1.85* (1.11–3.08) | N.S. |

| Maternal Rejection | 1.29* (1.01–1.64) | N.S. | 1.35a (0.99–1.86) | N.S. | 1.25* (1.00–1.56) | N.S. | 1.30a (0.95–1.77) | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. |

| Maternal Smoking | 1.49** (1.16–1.90) | 1.50* (1.09–2.05) | N.S. | 1.25a (0.96–1.64) | 1.21a (0.97–1.51) | N.S. | N.S. | 1.29* (1.02–1.64) | N.S. | N.S. |

Notes:

p<0.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001 (two-tailed tests);

Each of the independent variables was continuous and standardized;

NN = non- or experimental cigarette smoking/non- or experimental marijuana use; LL = late-starting cigarette smoking/late-starting marijuana use; OM = occasional cigarette smoking/moderate marijuana use; HO = heavy cigarette smoking/occasional marijuana use; and HH = heavy cigarette smoking/heavy marijuana use.

Maternal identification, maternal affection, and maternal rejection were based on youth reports; maternal satisfaction, resistance to maternal control, and maternal smoking were based on mothers’ reports.

4. Discussion

The present study extends prior research by examining patterns of comorbid smoking and marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood, and by the inclusion of several familial predictors of these comorbid trajectories. Approximately one-third of the sample did not engage in either cigarette smoking or marijuana use, one-third used both substances concurrently, and one-third of participants predominantly used one substance or the other over time.

Consistent with our theoretical framework (FIT; Brook et al., 1990), findings showed that the quality of the mother-child mutual attachment relationship, and maternal smoking, predicted trajectory group membership. Non- or experimental cigarette smokers/marijuana users (NNs) demonstrated greater maternal-child protective factors, and fewer risk factors, than all other trajectory groups, except the late-starters (further discussed below). Conversely, the HH group reported a weaker relationship with their mothers, and had more maternal smoking, than all other groups. The two mixed groups (OMs and HOs) showed intermediary levels of maternal risk and protective factors. Maternal identification, mother-child conflict, maternal affection, and maternal smoking were the most potent predictors of trajectory group membership.

According to FIT (Brook et al., 1990), children with a strong parental mutual attachment are more likely to a) identify with that parent, b) model the parent’s prosocial behavior, (Berenson, Crawford, Cohen, & Brook, 2005), and c) develop emotional self-regulation; all of which may aid the child in refraining from substance use. Conversely, individuals with poor parental attachment may have greater difficulty in regulating emotions and, therefore, engage in substance use to cope with emotional dysregulation (Caspers, Cadoret, Langbehn, Yucuis, & Troutman, 2005). Parental smoking has also been found to predict offspring tobacco and marijuana use, via e.g., role modeling (White, Johnson, & Buyske, 2000), fewer smoking rules (Emory, Saquib, Gilpin, & Pierce, 2010), and genetic predisposition (e.g., Lynskey, Agrawal, & Heath, 2010).

Contrary to our hypothesis, maternal factors did not differentiate between LL and NN group membership. Findings suggest that maternal influences were effective in restraining cigarette smoking and marijuana use among LL users (over one-fifth of our sample) until approximately age 16, but not thereafter. It is possible that social, personal, contextual, and/or hormonal changes occur during late adolescence which could affect susceptibility to comorbid smoking and marijuana use among this group.

4.1 Limitations

One limitation of the present research is that the sample is predominantly white and, therefore, we cannot generalize our findings to other racial/ethnic groups. Second, our data are based on self-report, and did not include biological measures of cigarette or marijuana use. However, prior research has shown self-report of substance use to be valid and reliable (Harrison, Martin, Enev, & Harrington, 2007).

Despite these limitations, our developmental trajectory approach identified groups of adolescents most at-risk for comorbid cigarette smoking and marijuana use. Moreover, risk and protective aspects of the mother-child relationship, as well as maternal smoking, were found to predict comorbid trajectory group membership from adolescence to adulthood.

4.2 Clinical Implications

Overall, the patterns of comorbid smoking and marijuana use shown in all trajectory groups (except the NNs) suggest that smoking prevention and cessation programs should include assessment and, as needed, treatment of marijuana use, and vice-versa. In addition, members of the groups with the highest levels of comorbid smoking and marijuana use should be referred to treatment, as they may be most at-risk for impaired functioning, health problems, and other illicit drug use/abuse/dependence (e.g., Fischer et al., 2010). The pattern of comorbidity shown by the LL group also suggests the need for repeated assessments throughout adolescence. Finally, adolescent prevention programs and clinical interventions might enlist the mother’s participation (e.g., family therapy), while adult treatment programs should address the earlier mother-child attachment relationship.

References

- Avgar A, Bronfenbrenner U, Henderson CR., Jr Socialization practices of parents, teachers, and peers in Israel: kibbutz, moshav, and city. Child Development. 1977;48:1219–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Berenson KR, Crawford TN, Cohen P, Brook J. Implications of identification with parents and parents’ acceptance for adolescent and young adult self-esteem. Self and Identity. 2005;4:289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1990;116:111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Lee JY, Finch SJ, Brown EN. Course of comorbidity of tobacco and marijuana use: psychosocial risk factors. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:474–482. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Cohen P. Some models and mechanisms for explaining the impact of maternal and adolescent characteristics on adolescent stage of drug use. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- Butters JE. Family stressors and adolescent cannabis use: a pathway to problem use. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:645–654. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers KM, Cadoret RJ, Langbehn D, Yucuis R, Troutman B. Contributions of attachment style and perceived social support to lifetime use of illicit substances. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psycholology. 2000;19:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. The relationship between cannabis use and other substance use in the general population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;64:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Martino SC, Collins RL. Marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: multiple developmental trajectories and their associated outcomes. Health Psychology. 2004;23:299–307. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emory K, Saquib N, Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. The association between home smoking restrictions and youth smoking behaviour: a review. Tobacco Control. 2010;19:495–506. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.035998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Rehm J, Irving H, Ialomiteanu A, Fallu JS, Patra J. Typologies of cannabis users and associated characteristics relevant for public health: a latent class analysis of data from a nationally representative Canadian adult survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19:110–124. doi: 10.1002/mpr.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Eccles JS, Peck S, Malanchuk O. The influence of family relations to trajectories of cigarette and alcohol use from early to late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LD, Martin SS, Enev T, Harrington D. DHHS Publication No SMA 07-4249, Methodology Series M-7. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult substance use. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:723–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the Future: Questionnaire responses from the nation’s high school senior, 2005. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Agrawal A, Heath AC. Genetically informative research on adolescent substance use: methods, findings, and challenges. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti NC, Stice E, Springer DW. Substance use and abuse trajectories across adolescence: a latent trajectory analysis of a community-recruited sample of girls. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/Mplus%20Users%20Guide%20v6.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking and their correlates from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:400–410. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s report of parental behavior: an inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES, Finkelstein NW. Child behavior toward parents: an inventory and factor analysis; Paper presented at: 83rd Annual Meeting of American Psychological Association; Chicago, IL. 1975. August 30–September 2, [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Johnson V, Buyske S. Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use. A growth curve analysis. Substance Abuse. 2000;12:287–310. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Wiesner M. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: predictors and outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:1007–1027. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]