Abstract

The present review focuses on recent studies from our laboratory examining the neural circuitry subserving rat maternal motivation across postpartum. We employed a site-specific neural inactivation method by infusion of bupivacaine to map the maternal motivation circuitry using two complementary behavioral approaches: unconditioned maternal responsiveness and choice of pup- over cocaine-conditioned incentives in a concurrent pup/cocaine choice conditioned place preference task. Our findings revealed that during the early postpartum period, distinct brain structures, including the medial preoptic area, ventral tegmental area and medial prefrontal cortex infralimbic and anterior cingulate subregions, contribute a pup-specific bias to the motivational circuitry. As the postpartum period progresses and the pups grow older, our findings further revealed that maternal responsiveness becomes progressively less dependent on medial preoptic area and medial prefrontal cortex infralimbic activity, and more distributed in the maternal circuitry, such that additional network components, including the medial prefrontal cortex prelimbic subregion, are recruited with maternal experience, and contribute to the expression of late postpartum maternal behavior. Collectively, our findings provide strong evidence that the remarkable ability of postpartum females to successfully care for their developing infants is subserved by a distributed neural network that carries out efficient and dynamic processing of complex, constantly changing incoming environmental and pup-related stimuli, ultimately allowing the progression of appropriate expression and waning of maternal responsiveness across the postpartum period.

Keywords: Bupivacaine neural inactivation, Conditioned place preference, Maternal motivation, medial prefrontal cortex, medial preoptic area, nucleus accumbens, Postpartum period, ventral tegmental area

Introduction

In rats and other mammals, the maternal condition is associated with a constellation of profound behavioral adaptations mediated by underlying physiological and neuroendocrine processes that allow the postpartum female to effectively care for her young following parturition. The hormonal events associated with late pregnancy and parturition initially activate the maternal neural circuitry to coordinate the immediate maternal responsiveness of the parturient female rat upon her first exposure to pups, however this hormonal influence is transient (1). Thereafter, the continued sensory experiences acquired by the mother while interacting with her pups are thought to be instrumental for the subsequent continuance of maternal responsiveness (2, 3).

During the next 3 to 4 weeks following parturition, the postpartum female rat will focus exceptional attentional resources, and allocate a significant amount of her time and energy to the care and protection of her rapidly developing pups until they are weaned (4, 5, 6, 7). Even though postpartum female rats remain highly responsive to their young for a considerable period after parturition, her maternal responsiveness undergoes considerable plasticity from birth to weaning, resulting in marked variations in maternal care across postpartum attuned to the rapidly changing needs of the young as they grow and develop (4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Indeed, successful rearing of the offspring requires continual updating of incoming sensory information and learning to flexibly adjust appropriate maternal behaviors to the particular behavioral capacities and physiological needs of the developing pups, while allocating behavior in a manner biased toward offspring’s care and protection in a complex, dynamic environment, where many other incentives are available. Accordingly, this vitally important task requires coordination between sensory, cognitive and motor systems to shape the mother’s behavior adaptively for the survival and well-being of the pups.

The present review focuses on recent studies from our laboratory examining the neural circuitry underlying maternal motivational processes that both ensure the continued allocation of the mother’s behavior toward offspring (over alternative competitive incentives), and orchestrate appropriate maternal caregiving responses with considerable plasticity in relation to the developmental stage of the pups. We employed a site-specific neural inactivation method by infusion of bupivacaine hydrochloride (an amide local anesthetic which blocks voltage-dependent sodium channels) to map the maternal motivation circuitry using two complementary behavioral approaches: unconditioned maternal responsiveness and a pup/cocaine choice conditioned place preference (CPP) task. Our findings demonstrated that during the early postpartum period, specific brain structures contribute a pup-specific bias to the motivational circuitry. With the progression of the postpartum period, however, our findings revealed that the functional role of several of these structures changes, likely to allow for the changing expression and waning of maternal responsiveness that ultimately promotes the independence of the young.

Assessing maternal motivation across the postpartum period

A series of studies in our laboratory have focused on the temporal dynamics of maternal responsiveness across the postpartum period, revealing a progressive reduction in the allocation of the mother’s time and care-giving behaviors in relation to the developmental needs of the pups (7). Our results confirm and extend those reported over the past several decades (4, 5, 8, 10). Briefly, the first half of the postpartum period is characterized by an intensive maternal commitment of behavior, time and energy required for the care of the altricial newborn pups. Early postpartum females spend virtually all of their time with the pups, rarely leaving the litter unattended and only for very short periods of time. Furthermore, the majority of this time is consumed by active care-giving and nursing behaviors. At the beginning of the second half of the postpartum period, the pups undergo rapid and dramatic developmental changes (12), and by the time pups are 12–16 days old, they are much more self sufficient. They can see, hear, thermoregulate, eliminate waste independently, and are mobile actively seeking out the mother for nourishment and care-taking behaviors. As the pups grow older and change physically and behaviorally, the mother increasingly distances herself from the pups, by PPD12 spending less than 55% of her time in contact with them. Thus, pups are left alone more frequently and for longer durations. This is accompanied by a significant decrease in maternal responses when with the pups, particularly active care-giving behaviors, such as pup retrieval, pup licking, and nest building, which decline rapidly from PPD12 to very low levels around PPD16. Nursing bouts also become progressively shorter and inter-bout intervals become longer from PPD10–12 onward, relative to the first 10 postpartum days following parturition (13, 14, 15).

Most, if not all, of the above-mentioned differences between early and late postpartum maternal behavior become evident by employing fine-grained analysis of maternal care-giving responses directed toward pups during a 30-min test, including latency, frequency, and duration of the various active and huddling/nursing maternal behaviors. As a result of our extended analysis over the entire postpartum period, two distinct behavioral stages characterizing the first half (early: PPD7–8) and the second half (late: PPD13–14) of the postpartum period were selected to investigate the functional role of discrete brain structures in the evolving expression of maternal behavior. Thus, early postpartum females readily retrieve and group all pups into the nest, express more licking and nest building behaviors, and adopt nursing postures faster and for longer durations compared to late postpartum females.

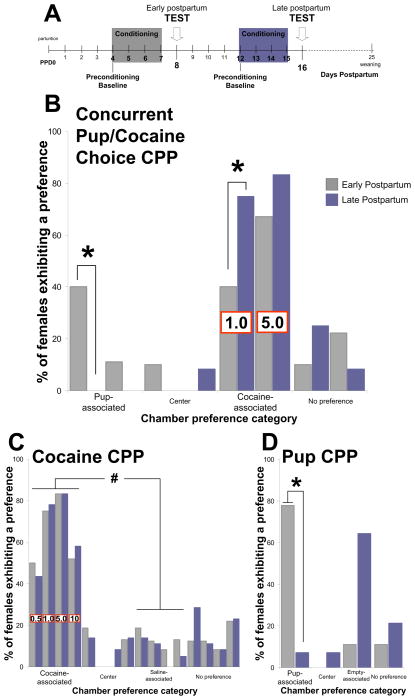

We originated and have used extensively a concurrent pup/cocaine choice conditioned place preference task, based on a modification of the basic conditioned place preference (CPP) procedure. The CPP procedure has been used widely to assess the reinforcing properties of natural and pharmacological stimuli and the behavioral and neural processes involved in context-induced stimulus-seeking (16). In an often-used example of the CPP paradigm, animals are conditioned to associate a uniquely featured environment (CS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US) with incentive motivational salience and an alternative environment with a neutral “control” stimulus. Building upon this procedure, our laboratory originated a version of a choice CPP task (17) to examine the conditioned responses of postpartum maternal rats when given a choice between environments associated with two motivationally significant alternatives: maternal interaction with pups or preferred doses of cocaine administration (1.0 and 5.0 mg/kg intraperitoneal:IP), either at early or late postpartum time points. As shown in Figure 1B, results demonstrated that even at these preferred doses of cocaine, the conditioned preferences of females for environments associated with cocaine are substantially reduced when pup-associated environments became the alternative option, in early, but not late postpartum time points (18). It should be noted that a dose of 1.0 mg/kg cocaine produces a bimodal distribution of preferences, with a roughly equal number of females choosing pup- and cocaine-associated environments. Consequently, this dose of cocaine was used in subsequent experiments to allow sensitive assessment of manipulations that either increase or decrease preferences for pup- or cocaine-associated environments.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the conditioned responses of postpartum females across postpartum during the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP task, the cocaine-induced CPP, or the pup-induced CPP procedure. (A) Timing of conditioning and testing in the CPP procedure; (B) Conditioned environment preferences during the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP test session, after conditioning with IP cocaine injection of either 1.0 or 5.0 mg/kg and maternal interaction with pups; cocaine doses are listed on bars representing cocaine-associated preference, and remain consistent across all chamber preference categories (C) Conditioned environment preferences during the cocaine-CPP test session, after conditioning with IP injections of either 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 or 10 mg/kg cocaine and saline; cocaine doses are listed on bars representing cocaine-associated preference, and remain consistent across all chamber preference categories. (D) Conditioned environment preferences during the pup-CPP test session, after conditioning with maternal interaction with pups and no specific unconditioned stimulus (empty chamber). *denotes significant differences at P<0.05 between postpartum groups, and # indicates significant within-group differences.

In additional studies we have demonstrated that cocaine remains highly reinforcing throughout postpartum, readily inducing robust CPP across a wide range of doses equally in early and late postpartum, with the most robust preferences at 1.0 and 5.0 mg/kg IP cocaine (19; Figure 1C). Moreover, plasma levels of cocaine and its metabolites, as well as their respective time courses, do not change substantially across postpartum, nor do the effects of cocaine on locomotor activity (20, 21). In contrast, the robust conditioned preference of early postpartum females for pup-associated environments markedly declines with the progression of the postpartum period (22; Figure 1D). Importantly, the unconditioned and conditioned maternal responses to pups are highly correlated with each other, across the postpartum period (7, 17, 18, 22, 23, 24).

The concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP task assesses how time is allocated in seeking pup-and alternative competing cocaine-conditioned incentives in a conflict situation, and hence provides a useful framework for studying the neural mechanisms involved in this decision process. The decision process in this concurrent choice task involves the knowledge of each CS-US association, as well as an evaluation of the incentive value of each competing representation, to choose one alternative over the other one. The data gathered from this concurrent choice CPP task further advance our understanding of maternal motivation circuitry by specifically examining those neural processes biasing the behavioral allocation toward offspring and related stimuli when challenged by a highly competitive, concurrently available alternative, such as cocaine-conditioned incentives. Accordingly, use of the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP procedure in combination with fine-grained analysis of maternal behavior at both early and late postpartum stages has proven to be a particularly powerful approach to examine the neural circuitry subserving maternal motivation, particularly in specifying the functional contribution of the medial preoptic area (mPOA), the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and distinct medial prefrontal cortical (mPFC) subregions.

Neural Circuitry of Motivation

In recent years a great deal of progress has been made in advancing our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying motivation. Considerable evidence from both animal and human research has revealed that motivational processes involved in the performance of goal-directed behaviors are mediated by a distributed network of brain structures, including the orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices, the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA), the hippocampus, the nucleus accumbens (NA) and its dopaminergic inputs from the VTA. The NA receives convergent excitatory inputs from all the above-mentioned cortical and subcortical structures (25, 26, 27, 28, 29), and hence has long been considered a corticolimbic-motor interface within this network (30, 31, 32). The major efferents of the NA are to the ventral pallidum (VP), substantia nigra pars reticulata, VTA, as well as several hypothalamic and brainstem nuclei (33). As a major modulatory component of this circuitry, NA dopamine (DA) is thought to play a critical role in modulating different aspects of goal-directed behaviors (34, 35, 36, 37, 38).

Connectivity related to maternal responsiveness

During the maternal state, additional brain regions are likely recruited and contribute specific interoceptive and exteroceptive pup-related information to this circuitry to promote appropriate maternal responsiveness to infant stimuli. Among the brain structures critically involved in postpartum maternal responsiveness, it is widely recognized that the medial preoptic area (mPOA) acts as a primary integrative locus, orchestrating maternal responsiveness. The mPOA receives converging pup-related information from multiple sensory modalities (3, 39) and is a primary neural site where the hormones of pregnancy act to promote maternal responsiveness to pup-related stimuli at parturition (1, 40, 41, 42). Furthermore, the mPOA has connections with the VTA, NA, and mPFC (43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48) that potentially allow pup-responsive mPOA neurons to interact with the motivational circuitry to bias the allocation of the mother’s behavior toward offspring.

Our previous work examining expression of the c-Fos protein product of the immediate early gene and cocaine- and amphetamine-related transcript (CART) peptide as markers of neuronal activation, showed that subsets of neurons within the mPFC, NA, BLA and mPOA were differentially activated depending on whether postpartum maternal rats expressed a conditioned preference for pup- or cocaine-associated environments in a concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP procedure (49). Notably, the mPOA was the only region that showed substantially greater c-Fos- and CART-IR neurons when postpartum females chose pup- over cocaine- associated environments (49). Postpartum females that chose pup- over cocaine-conditioned incentives had elevated c-Fos-IR expression relative to control females within the mPFC IL and Cg1 subregions, as well as within the BLA. In addition, there were more CART-IR-expressing neurons in the nucleus accumbens core and shell of postpartum females that preferred the pup-associated environment than the control group. It is noteworthy that choice of pup-conditioned incentives in the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP task correlates with a pattern of enhanced Fos-IR that is topographically similar to that observed following maternal interaction with pups (50, 51, 52, 53). This is also consistent with fMRI work showing a robust activation of mesocorticolimbic structures in mother rats in response to pup’s sensory stimulation (54, 55). This map of neuronal activation was subsequently used to define our initial circuitry blueprint, directing us to examine the functional role of these potential key components to maternal motivation.

Mapping maternal motivation circuitry

A methodological approach using transient site-specific neuronal inactivation by infusion of bupivacaine hydrochloride was chosen to allow the analysis of the function of discrete brain regions in a temporally specific manner (56). Specifically for the CPP procedure, this method allows regional inactivation during the expression of a previously learned and established CPP, without interfering with the prior associative learning of the subject during conditioning (i.e. acquisition phase), or with the memory consolidation of these learned associations, both needed to establish a CPP. Importantly, in contrast to permanent lesions, this method does not disrupt maternal caregiving in the homecage, nor during conditioning phases of the CPP procedure, so that interpretation of the inactivation of a region is not confounded by effects other than at CPP test. Furthermore, bupivacaine inactivation can be repeated during multiple experimental sessions in the same animal, allowing the longitudinal study of maternal behavior in the same individual females across postpartum (i.e. to serve as their own controls), which increases data reliability (56, 57). Bupivacaine is an amide-linked local anesthetic that, like the structurally similar lidocaine, produces an immediate transient neuronal inactivation by blocking voltage-dependent sodium channels (58, 59, 60), and unlike other pharmacological agents (i.e. other NA+ channel blockers like TTX or specific to a particular receptor, such as the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol), its effect is much shorter in duration, has a considerably smaller radius of functional spread, and does not ordinarily produce neuronal damage (56, 57, 61, 62).

medial preoptic area

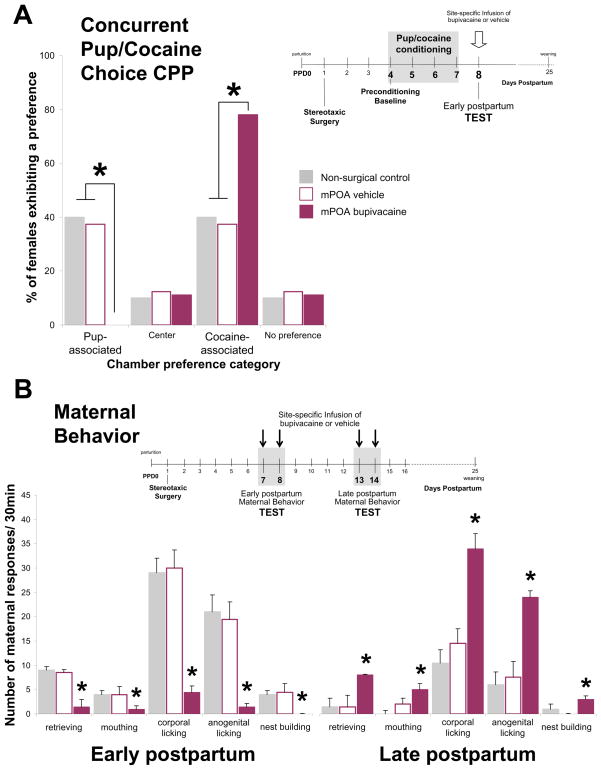

We started the examination of the neural circuitry modulating maternal motivated responses by investigating the functional role of the mPOA on processing the incentive value of pup-associated cues and influencing response allocation for pup- over cocaine-associated environments in the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP task. Females underwent pup/cocaine conditioning during PPD4–7 and were tested on PPD8 in the absence of the unconditioned stimuli, following infusion of either bupivacaine or saline vehicle into the mPOA or immediately adjacent control sites. As shown in Figure 2A, when given a choice between environments associated with maternal interaction with pups versus 1.0 mg/kg IP cocaine, functional inactivation of the mPOA substantially altered the choice behavior, biasing the preference of early postpartum females toward cocaine-associated environments, such that almost all females preferred the cocaine-associated environment and none the pup-associated option, highly contrasting with the bimodal distribution of conditioned preferences of both non-surgical and intra-mPOA vehicle-treated control groups for pup- and cocaine-associated environments. In additional experiments, the effect of transient inactivation of the mPOA on expression of conditioned responding induced by environments associated with either cocaine versus saline injections (cocaine-induced CPP) or maternal interaction with pups versus no specific unconditioned stimulus (empty chamber; pup-induced CPP) was examined separately. While transient inactivation of the mPOA had no impact on the motivational responsivity of early postpartum females to cocaine-related stimuli, this manipulation completely blocked the expression of the conditioned preferences for the pup-associated environment.

Figure 2.

Effect of mPOA inactivation on maternal motivated responses. (A) Effect of transient inactivation of the mPOA on the choice of pup- versus cocaine-associated environments during the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP test session. Data shown are from early postpartum non-surgical control females and mPOA-cannulated females following either vehicle or inactivation treatment with 2% bupivacaine. * denotes significant differences at P<0.05 between groups; (B) Effect of transient inactivation of the mPOA on median±SIQR number of active maternal responses over a 30-min behavioral test. Female rats were tested on PPD7 and 8 and then again on PPD13 and 14. Data shown are from non-surgical control females and mPOA-cannulated females following either vehicle or inactivation treatment with 2% bupivacaine. *Significant difference at P<0.05 on bupivacaine versus saline test days (within-group comparison) and versus the non-surgical control females (between-group comparison).

Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence that the functional integrity of the mPOA is necessary for the expression of context-induced pup- but not cocaine-seeking behavior, and further suggest that the competing properties of pup- over alternative cocaine-conditioned incentives rely on the functional integrity of the mPOA to provide relevant pup-related information to the circuitry processing the choice behavior (18). Several additional lines of research support the notion that the mPOA is involved in incentive motivational processes, particularly in relation to social incentives, including maternal and sexually motivated behaviors. For instance, using an operant bar-pressing procedure, Lee and colleagues (63) demonstrated that bar-pressing for access to pups in early postpartum females is substantially reduced following permanent mPOA lesions, while food-reinforced bar-pressing was unimpaired. Similarly, several reports using both permanent mPOA lesions and pharmacological manipulations have demonstrated involvement of the mPOA in sexual incentive motivation in both male and female rats (64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76).

As discussed above, the marked transition in maternal responsiveness that occurs across the postpartum period is well documented (4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11), as is the necessary role of the mPOA in both the onset and early expression of maternal behavior (3). We have extended the understanding of the neural basis of maternal responsiveness by examining the functional role of the mPOA in the regulation of maternal behavior throughout postpartum, particularly extending into the late postpartum, a relatively under-examined period (23). This study used a within-subject design to examine the functional role of the mPOA in the regulation of maternal behavior over two distinct behavioral stages of the postpartum period. Each postpartum female was tested for maternal behavior at both early and late postpartum days, following intracranial infusion of either bupivacaine or saline vehicle into the mPOA or anatomical control areas.

Collectively, these results demonstrated that the mPOA is differentially engaged throughout postpartum in orchestrating appropriate maternal responses to the different needs of the developing pups, from a necessary facilitatory role during early postpartum, to an inhibitory role during late postpartum (23). During the first week postpartum, and consistent with previous studies (45, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81), the mPOA was found to be a necessary component of the maternal circuitry facilitating the intensive care-giving activity required by the newborn pups, since its functional inactivation severely and selectively disrupted active maternal components of female rats, including retrieving, licking and nest building, whereas nursing behaviors were unaffected (Figure 2B).

In a novel finding inactivation at the very same mPOA location had a completely different effect during late postpartum, causing a significant increase in all active components of maternal behavior compare to that seen after vehicle infusion (Figure 2B). Further details of the approach and results can be found in Pereira and Morrell, 2009. The opposite effect of mPOA inactivation during early versus late postpartum demonstrates that the mPOA is differentially engaged throughout postpartum in the regulation of maternal responsiveness. For instance, the fact that inactivation of the mPOA did not inhibit maternal behavior in late postpartum, whereas severely disrupted early postpartum maternal behavior suggests that with the progression of the postpartum period, the necessary contribution of the mPOA to the expression of maternal behavior wanes in its importance. Furthermore, the finding that mPOA inactivation in fact facilitated late postpartum maternal behavior further suggests that the regulation of maternal responsiveness is more at this point distributed in the maternal circuitry such that additional network components are recruited with maternal experience. An important implication of this is that mPOA may remain sufficiently involved in aspects of maternal responsiveness, allowing the changing expression and waning of maternal behavior across postpartum by suppressing the ability of additional network components to inappropriately influence the expression of maternal behavior (23).

Nucleus accumbens and its DAergic input

Considerable evidence suggests that the NA is a nodal integration site for the convergence of corticolimbic inputs (25, 29, 30, 31, 82, 83) under the modulatory influence of DA-afferents from the VTA (84). Contemporary theories of the behavioral functions of NA DA neurotransmission propose that DA participates in information processing within the NA that underlie different aspects of goal-directed behaviors, including response selection, behavioral activation, and effort-related processes (34, 36, 37, 38, 85, 86, 87), by modulating the effects of specific corticolimbic afferents to the NA, thus influencing the transmission of information to output areas, and ultimately affecting the behavioral strategy of the animal (31, 32, 37, 83, 84, 88).

In common with other motivated behaviors, DA neurotransmission in NA is essential for the normal expression of the active components of maternal behavior. Interference with accumbens DA neurotransmission, following either DA antagonism or accumbens DA depletion, disrupts early postpartum maternal motivation by selectively affecting most forms of active maternal behaviors, while leaving nursing behaviors relatively intact (89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94). Furthermore, studies employing in vivo neurochemical monitoring techniques have reported that extracellular levels of DA in accumbens were significantly elevated during maternal interaction with pups in early postpartum females (95, 96), further characterizing the role of accumbens DA transmission in the execution of maternal behavior. In an elegant series of studies, Numan and colleagues (45, 97) have provided considerable evidence in support of the hypothesis that the mPOA modulates motivational aspects of early postpartum maternal responsiveness toward pups by influencing VTA DA neurons that project to the NA.

Based upon studies of DAergic involvement in maternal responsiveness, coupled with our novel findings showing a critical involvement of the mPOA, which has connections with the VTA, in the modulation of both the unconditioned behavioral activation produced by pups (23), as well as the expression of conditioned responses to pup-related stimuli (18), a series of experiments were conducted in our laboratory to investigate the functional contribution of the VTA and NA to the expression of pup-induced CPP. Transient inactivation of the VTA and NA had remarkably different behavioral effects. Specifically, inactivation of the VTA prior to CPP testing completely blocked the conditioned preferences for the pup-associated environment, significantly contrasting the robust pup-CPP found in non-surgical and intra-VTA vehicle-treated control groups (98). Thus, none of the VTA inactivated females preferred the environment associated with pups, whereas the majority of control females preferred the pup-associated option. In contrast, inactivation of the NA had no impact on the motivational responsivity of postpartum females to pup-associated stimuli, compared with the non-surgical and intra-NA vehicle-treated control groups (Pereira and Morrell, unpublished results).

In order to obtain a more complete picture of the role of VTA and NA in maternal motivation, additional studies were conducted to examine the functional role of VTA and NA in the expression of early postpartum maternal behavior. In parallel with the above-reviewed findings, VTA inactivation selectively and severely disrupted active components of early postpartum maternal behavior (98), whereas functional inactivation of the NA did not (Pereira and Morrell, unpublished results). Remarkably, the impairments in early postpartum maternal behavior following VTA inactivation are strikingly similar to the effects of mPOA inactivation, and both outcomes are similar to those reported following DA antagonism in the NA (91, 92, 93, 94).

In order to reconcile these seemingly divergent findings, namely evidence of a critical role of the VTA but no demonstrable consequence of inactivation of NA, a major terminal field for VTA DAergic neurons, it is essential to consider prevailing models of basal ganglia function. These models propose that the NA, similar to dorsal neostriatum, consists of distinct populations of medium spiny GABAergic projection neurons that selectively express either D1 (positively coupled to cAMP) or D2 (negatively coupled to cAMP) receptors (99, 100, 101) and respectively project either directly or indirectly to basal ganglia output nuclei, namely substantia nigra pars reticulata and pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108). Through these opposing direct and indirect output pathways, NA neurons are proposed to select appropriate behavioral responses while inhibiting competing ones. One possibility that may account for the different behavioral effects of inactivation of the VTA versus the NA is related to the nature of the impact of the manipulation on the NA. For instance, our findings following VTA inactivation are consistent with studies showing that manipulations that selectively interfere with NA DA neurotransmission, including inactivation of the VTA (which contains the DAergic neurons that project to the NA), intra-NA DA receptor antagonism, and depletion of DA within the NA, all result in a marked impairment in behavioral responding to a variety of unconditioned and conditioned incentive stimuli (109, 110, 111), including pups and related stimuli (89, 90, 98, 112). In contrast, methods that result in transient inactivation or permanent cell body lesion of the NA uniformly inhibit all NA-neurons, regardless of medium spiny neuron subtype or their efferent destination, have virtually no effect on motivated behaviors (111, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118). Given the distinct populations of medium spiny neurons within the NA, transient NA inactivation might result in effects that effectively cancel each other at the level of basal ganglia output nuclei, with no net change in behavior. An alternative possibility relates to the notion that NA neurons appear to exert an inhibitory influence on behavior (119). According to this hypothesis, transient inactivation of the NA produces a general disinhibition of behavioral responding to stimuli regardless of their incentive value. Further consistent with such a disinhibitory effect, NA inactivation has been associated with increased spontaneous locomotion (111, 120, 121).

Viewed collectively, the evidence favors the idea that NA is an important locus at which DA facilitates activational aspects of maternal motivation, behavioral allocation and responsiveness toward pup-related stimuli. However, the precise role of accumbens DA in expression of pup-induced CPP is at best tentatively determined, and warrants further study using NA D1 and D2 receptor antagonism. Alternatively, it has been shown that a subset of VTA DA-containing neurons to the NA co-release glutamate (122, 123, 124), which may initiate the process that is consequently modulated by DA (122, 125). Hypothetically, in relation to our specific behavioral case, pup-associated stimuli could activate DA neurons in VTA, but pup-seeking behavior in response to conditioned stimuli might be sustained by the concomitant glutamate release. Furthermore, in addition to the extensively studied DA projections of the VTA, several studies have also demonstrated that some GABA- and glutamate-containing neurons project from the VTA to the NA (126, 127, 128), raising the possibility that the conditioned incentives of pups might be mediated by a VTA dopamine-independent mechanism. Finally, the VTA contains neurons that project to a variety of structures, including the mPFC, amygdala, mPOA, and VP (129, 130, 131, 132, 133), which may also importantly contribute to different aspects of goal-directed behaviors. Additional studies are necessary to further refine our understanding of the contribution of the VTA-accumbens projection system, including its DAergic, glutamatergic and GABAergic components, to maternal motivation.

medial Prefrontal Cortex

We continued to investigate the neural circuitry that regulates response selection among competing alternatives by examining the role of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which is interconnected with components of the motivational circuitry, including mPOA, VTA and NA, and is involved in stimulus recognition and executive functions contributing to attentional selection, optimal organization and planning, flexibility and decision-making in relation to complex goal-directed behaviors (134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140). The rodent mPFC can be functionally and anatomically subdivided into three distinct subregions - anterior cingulate (Cg1), prelimbic (PrL), infralimbic (IL) (141). The differences in the behavioral roles of these distinct subdivisions are thought to be due, at least in part, to differences in their extrinsic connections with specific striatal, limbic, midbrain, and preoptic-hypothalamic nuclei (48, 138, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152).

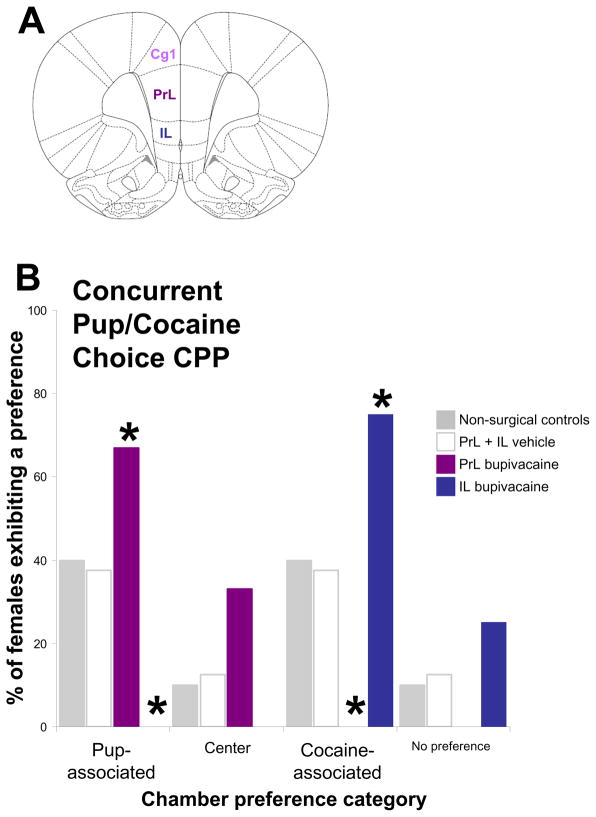

Reversible neural inactivation by infusion of bupivacaine into these three distinct subregions of the mPFC was used to examine their respective roles in the choice of pup- versus cocaine-associated environments in a concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP task (153, Pereira and Morrell, in preparation). When given a choice between environments associated with maternal interaction with pups or cocaine administration, it was found that inactivation of PrL biased the choice of early postpartum females toward pup- over competing cocaine-conditioned incentives, such that almost all females preferred pup- and none the cocaine-associated option (Figure 3). This is in marked distinction from the outcome of inactivating the IL which had the opposite effect on the choice behavior, biasing the preference of early postpartum females for cocaine-over competing pup-conditioned incentives, such that almost all preferred cocaine- and none the pup-associated option in the concurrent pup/cocaine CPP task (Figure 3; 153, Pereira and Morrell, in preparation). However, when cocaine-induced CPP and pup-induced CPP were examined individually, the effect of PrL or IL inactivation on the expression of conditioned responses was much less pronounced. Thus, transient inactivation of the PrL subregion only moderately reduced CPP of postpartum females for cocaine-related stimuli, while a similar effect was observed for pup-CPP following IL inactivation.

Figure 3.

Effect of transient mPFC subregion-specific inactivation on the choice of pup- versus cocaine-associated environments during the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP test session. (A) Graphic illustration of a cross-section of the rat brain labeling the mPFC subregions, including the anterior cingulate (Cg1), prelimbic (PrL), and infralimbic (IL) cortices (adapted from Paxinos and Watson, 2004). (B) Effect of transient inactivation of mPFC PrL or IL on the choice of pup- versus cocaine-associated environments during the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP test session. Data shown are from non-surgical control females, mPFC PrL + IL vehicle-treated, mPFC PrL bupivacaine-treated, and mPFC IL bupivacaine-treated early postpartum females. Conditioned environment preferences during the concurrent pup/cocaine choice CPP test session did not differ between mPFC PrL vehicle-treated and mPFC IL vehicle-treated groups and were pooled for graphical representation purposes. *denotes significant between groups differences at P<0.05.

Collectively, our findings indicate that IL and PrL subregions of the mPFC likely crucially participate in the resolution of the choice conflict, and are less directly involved in context-induced pup- or cocaine-seeking behavior, respectively, when conflict representations are not present. Nevertheless, the selective involvement of IL and PrL subregions is stimulus-specific as seen in the processes of mediating the pup- or cocaine-associated bias in response-conflict situations, in which postpartum female rats have to choose between competing alternative representations. In support of this conclusion, previous studies have shown that PrL is critically involved in cognitive aspects of cocaine-seeking behaviors, whereas mPFC IL is not (154, 155, 156, 157, 158).

We were particularly interested in examining the medial prefrontal cortical contribution to the expression of maternal behavior across the postpartum period. A separate experiment examined the effects of site-specific neural inactivation of these distinct mPFC subregions on the expression of maternal behavior in the first half (PPD7–8) versus the second half postpartum (PPD13–14), demonstrating distinct and dissociable mPFC subregion-specific contributions to the changing expression of maternal behavior across postpartum. Specifically, transient inactivation of IL subregion severely disrupted all components of early postpartum maternal behavior, whereas inactivation of PrL subregion did not (159, Pereira and Morrell, in preparation). It is worth mentioning that the effects of mPFC inactivation, in contrast to those of mPOA inactivation, also extended to nursing behaviors. Unlike our mPOA results showing selective disruptions on the active maternal components, mPFC IL-inactivated females did not direct their behavior toward pups, but instead engaged in other activities such as eating, drinking and resting during the maternal behavior test. Later in the postpartum period, however, assessment of the function of these same subregions indicated a change in their roles. Specifically, transient inactivation of the IL subregion had no effect on late postpartum maternal behavior, whereas inactivation of PrL severely disrupted the expression of maternal behavior (159, Pereira and Morrell, in preparation). Inactivation of Cg1 affected the organizational aspects of early and late postpartum maternal behavior, resulting in a behavioral effect distinct from that produced by inactivation of either IL or PrL subregions (159, Pereira and Morrell, in preparation).

The behavioral effects obtained in early postpartum after reversible mPFC subregion-specific inactivation confirm and extend those reported earlier following global lesion or inactivation of mPFC (160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165), by demonstrating a specific, necessary role for the IL subregion of mPFC in early postpartum maternal behavior. Our data also demonstrate that with the progression of the postpartum period, the necessary facilitatory role of the IL subregion wanes, while additional subregions, such as the PrL, are recruited and contribute to the expression of late postpartum maternal behavior.

Synthesis, concluding remarks and additional reflections

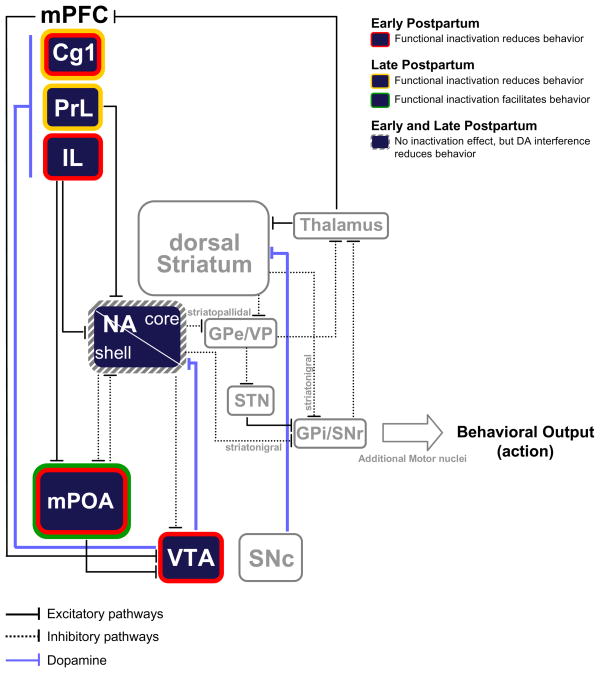

Collectively, our findings provide strong evidence that the remarkable ability of postpartum females to successfully care for their developing infants is subserved by a distributed neural network that carries out efficient and dynamic processing of complex incoming environmental and pup-related stimuli that is constantly changing across the postpartum period, ultimately promoting a progression of appropriate care-giving behavior (Figure 4). Specifically, our data strongly suggest that during early postpartum the integrated functional contribution of mPOA, VTA and mPFC IL and Cg1 is essential for the extensive maternal commitment of behavior, time and resources required for the care of altricial newborn pups. As the postpartum period progresses and the pups grow older, our findings further suggest that substantial functional reorganization of specific brain structures and their connections occurs, likely sculpted by the continuous experience of interaction with the developing pups, mediating the changing expression of maternal care-giving responses across postpartum. The combined analysis of the functional contribution of the mPOA, VTA, NA and mPFC to the unconditioned and conditioned responses to pups and associated stimuli has proven particularly powerful in specifying the role of each of the above structures in maternal motivation.

Figure 4.

A simplified schematic representing some of the neural circuitry that mediates aspects of maternal responsiveness across the postpartum period. Colored bands surrounding each structure highlight the behavioral effect of the bupivacaine inactivation of the given structure. Hatched-shaded bands indicate no effect of bupivacaine inactivation, but an effect under pharmacological manipulation or other conditions. These structures are linked via a complex network of excitatory and inhibitory connections (shown as solid and dotted lines, respectively). DAergic synapses are denoted by filled blue lines. The major projections of D1R-expressing striatonigral and D2R-expressing striatopallidal neurons are depicted. Cg1: anterior cingulate cortex; GPe: external globus pallidus; GPi: internal globus pallidus; IL: infralimbic cortex; mPFC: medial prefrontal cortex; mPOA: medial preoptic area; NA: nucleus accumbens; PrL: prelimbic cortex; SNc: Substantia nigra pars compacta; SNr: Substantia nigra pars reticulata; STN: subthalamic nucleus; VP: ventral pallidum; VTA: ventral tegmental area.

During early postpartum…

While our collective findings demonstrate that the competing properties of pup- over alternative cocaine-conditioned incentives rely on the integrated functions of the mPOA, VTA and mPFC IL components of the circuitry processing the choice behavior, they also suggest that each of these interconnected regions contributes distinct, yet complimentary functions. Specifically, these findings indicate that both the mPOA and the mPFC IL are part of an integrated neural network that influences the behavioral allocation toward pup-related stimuli, as the functional integrity of each of these two structures is necessary to promote the choice of pup- over competing cocaine-conditioned incentives. Equally informative about the functioning of these regions, our data also show that neither the mPOA nor the mPFC IL are necessary for the expression of context-induced cocaine-seeking behavior. On the other hand, transient inactivation of the mPOA, but not of mPFC IL, completely eliminated the ability of pup-associated environmental cues to promote pup-seeking behavior. Taken together, these findings suggest a primary role for the mPOA in encoding pup-related information and promoting goal-directed behaviors for pups and associated stimuli. In contrast, it is likely that the mPFC IL is primarily involved in the response selection among possible choices in a conflict situation.

The observation of dissociable functional roles of mPFC IL and mPOA is further supported by the differential effects obtained following inactivation of these regions on early postpartum maternal behavior. The fact that IL inactivation caused a greater disruption, severely affecting all components of maternal behavior, in contrast to the comparatively more selective effect of mPOA inactivation on only active maternal components, raises interesting implications for the basic understanding of the functional role of these structures in the modulation of early postpartum maternal motivation. Inactivation of mPFC IL caused early postpartum females to be impaired at either selecting maternal responses, sustaining maternal responsiveness to pups, or at disinhibiting responses to competing stimuli present in the home cage. Furthermore, without a functional mPFC IL, the intact mPOA was not sufficient to promote the female’s responsivity to pups in expression of maternal behaviors.

Taken together, it is tempting to speculate that the mPFC IL is primarily involved in guaranteeing the behavioral allocation toward pups and associated stimuli in complex environments where more than one relevant stimulus is available. Specifically, we posit that the mPFC IL, integral to various corticocortical and corticostriatal networks implicated in higher-order cognition, receives polymodal sensory input and has connections with several subcortical structures, including many involved in maternal behavior (mPOA, BST, VTA, NA, and the periaqueductal grey), is in a nodal position to integrate exteroceptive pup-related information with interoceptive information related to the maternal state, and to exert executive control to bias behaviors toward pups (48, 145, 146, 166, 167). In contrast, the mPOA is critically involved in mediating both the unconditioned behavioral activation produced by pups (23), as well as the conditioned responses to pup-associated stimuli (18), suggesting that the mPOA is a key component in motivational processing of pups and related incentive stimuli. Substantial evidence suggests that the mPOA regulates motivational aspects of early postpartum maternal responsiveness toward pups by influencing VTA DA projection neurons to the NA (45, 97, 112). Our finding that both the active components of maternal behavior and context-induced pup-seeking minimally require the concurrent functional integrity of the mPOA and the VTA (18, 23, 98), because following inactivation of either, functional integrity of the remaining one was insufficient to maintain these responses, further supports Numan’s model by suggesting that serial transmission of information between the mPOA and the VTA is required for motivational aspects of early postpartum maternal responsiveness (45, 97, 112).

Later in the postpartum period…

As the postpartum period progresses and the pups grow older, our findings suggest that the regulation of maternal responsiveness becomes progressively less dependent on mPOA and mPFC IL activity, and more distributed in the maternal circuitry, such that additional network components, including the mPFC PrL, are recruited with maternal experience and contribute to the expression of late postpartum maternal behavior.

The necessary roles of mPOA and mPFC IL demonstrated during early postpartum highly contrast the comparative lack of disruptive effect during late postpartum, indicating that with the progression of the postpartum period, the expression of maternal behavior can be executed without the cognitive regulation of the mPFC IL and the excitatory influence of the mPOA. In parallel, it appears that with the progression of the postpartum period the role of the mPOA changes, from promoting active maternal care giving in early postpartum to actively inhibiting maternal behaviors as the pups develop in later postpartum stages (23). Moreover, the disinhibitory effect of mPOA inactivation on maternal behavior in late postpartum resembled a type of habitual responding, as indicated by a lack of sensitivity of the maternal response to the developmental stage of the pups. Taken together, these data support the speculation that with the progression of postpartum, the mPOA might remain sufficiently involved in aspects of maternal responsiveness by suppressing the ability of additional network components to inappropriately influence maternal behavior in late postpartum, hence allowing the natural progression of maternal behavior that occurs in the postpartum period.

Highly contrasting with the necessary role of the mPFC IL during early postpartum, inactivation of IL in late postpartum had no impact on maternal behavior, suggesting that with the progression of the postpartum period, the mPFC IL no longer biases behavioral allocation toward pups. In parallel with a progressive waning of the role of mPFC IL, our findings suggest that mPFC PrL becomes involved in maternal responsiveness. This role transfer within subregions of the mPFC throughout postpartum might be related to the transition from goal-directed to habitual responding that probably occurs over time with continuous exposure to pups. This suggestion is consistent with considerable data supporting the general hypothesis that various regions of the mPFC regulate the transition between these behaviors presumably via glutamatergic efferent projections to the NA and the neostriatum (134, 151, 168).

Importantly, the changing role of distinct brain regions in the regulation of maternal responsiveness is consistent with the reduced CPP for pup-associated environments, overwhelmingly promoting the choice for cocaine-associated environments during late postpartum (7, 17, 22).

Ongoing studies in our laboratory involve disconnection procedures and intracranial administration of neurotransmitter-specific drugs to further refine the understanding of the neural circuitry that supports maternal responsiveness throughout the postpartum period. Obtaining a more complete understanding of the neural circuitry that orchestrates maternal responsiveness throughout postpartum is essential, not only for a better understanding of the nature of the mother–infant relationship under both adaptive and maladaptive circumstances, but also for developing strategies for treatment of maternal neuropsychiatric and drug use disorders during the postpartum period.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award and NIDA SOAR DA027945 awarded to MP and NIDA DA014025 awarded to JIM.

Abbreviations

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- Cg1

anterior cingulate cortex

- CPP

conditioned place preference

- IL

infralimbic cortex

- IP

intraperitoneal

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- mPOA

medial preoptic area

- NA

nucleus accumbens

- PPD

postpartum day

- PrL

prelimbic cortex

- VP

ventral pallidum

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

References

- 1.Bridges RS. Endocrine regulation of parental behavior in rodents. In: Krasnegor NA, Bridges RS, editors. Mammalian parenting: biochemical, neurobiological, and behavioral determinants. New York: Oxford Press; 1990. pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magnusson JE, Fleming AS. Rat pups are reinforcing to the maternal rat: Role of sensory cues. Psychobiology. 1995;23:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Numan M, Insel TR. The neurobiology of parental behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grota LJ, Ader R. Continuous recording of maternal behavior of Rattus norvegicus. Animal Behavior. 1969;17:722–729. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(70)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grota LJ, Ader R. Behavior of lactating rats in a dual-chambered maternity cage. Horm Behav. 1974;5:275–282. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(74)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Numan M, Woodside B. Maternity: neural mechanisms, motivational processes, and physiological adaptations. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124(6):715–41. doi: 10.1037/a0021548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira M, Seip KM, Morrell JI. Maternal motivation and its neural substrate across the postpartum period. In: Bridges RS, editor. The Neurobiology of the Parental Mind. San Diego (CA): Elsevier Academic Press; 2008. pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming AS, Rosenblatt JS. Maternal behavior in the virgin and lactating rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1974;86(5):957–72. doi: 10.1037/h0036414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira M, Ferreira A. Demanding pups improve maternal behavioral impairments in sensitized and haloperidol-treated lactating female rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175(1):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisbick S, Rosenblatt JS, Mayer AD. Decline of maternal behavior in the virgin and lactating rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;89(7):722–32. doi: 10.1037/h0077059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uriarte N, Ferreira A, Rosa XF, Sebben V, Lucion AB. Overlapping litters in rats: effects on maternal behavior and offspring emotionality. Physiol Behav. 2008;93(4–5):1061–70. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenblatt JS, Mayer AD, Siegel HI. Maternal behavior among nonprimate mammals. In: Adler N, Pfaff D, Goy RW, editors. Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology. Vol. 7. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 229–298. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattheij JA, Swarts HJ, van Mourik S. Plasma prolactin in the rat during suckling without prior separation from pups. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1985;108(4):468–474. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1080468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taya K, Sasamoto S. Changes in FSH, LH and prolactin secretion and ovarian follicular development during lactation in the rat. Endocrinol Jpn. 1981;28(2):187–196. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.28.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taya K, Greenwald GS. Peripheral blood and ovarian levels of sex steroids in the lactating rat. Endocrinol Jpn. 1982;29(4):453–459. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.29.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addiction Biology. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattson BJ, Williams SE, Rosenblatt JS, Morrell JI. Comparison of two positive reinforcing stimuli: pups and cocaine throughout the postpartum period. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:683–694. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.3.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira M, Morrell JI. The medial preoptic area is necessary for maternally motivated choice of pup but not cocaine-associated environments in postpartum rats. Neuroscience. 2010;167:216–231. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seip KM, Pereira M, Wansaw MP, Dziopa EI, Reiss JI, Morrell JI. Incentive salience of cocaine is remarkably stable across postpartum in the lactating female rat: route of administration and dose manipulations using place preference. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199(1):119–30. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1140-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernotica EM, Morrell JI. Plasma cocaine levels and locomotor activity after systemic injection in virgin and in lactating maternal female rats. Physiol Behav. 1998;64(3):399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wansaw MP, Lin SN, Morrell JI. Plasma cocaine levels, metabolites, and locomotor activity after subcutaneous cocaine injection are stable across the postpartum period in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82(1):55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wansaw MP, Pereira M, Morrell JI. Characterization of maternal motivation in the lactating rat: contrasts between early and late postpartum responses. Horm Behav. 2008;54(2):294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira M, Morrell JI. The changing role of the medial preoptic areas in the regulation of maternal behavior across the postpartum period: facilitation followed by inhibition. Behav Brain Res. 2009;205:238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seip KM, Morrell JI. Increasing the incentive salience of cocaine challenges preference for pup- over cocaine-associated stimuli during early postpartum: place preference and locomotor analyses in the lactating female rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194:309–319. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0841-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brog JS, Salyapongse A, Deutch AY, Zahm DS. The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338(2):255–78. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groenewegen HJ, Wright CI, Beijer AV, Voorn P. Convergence and segregation of ventral striatal inputs and outputs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:49–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGeorge AJ, Faull RL. The organization of the projection from the cerebral cortex to the striatum in the rat. Neuroscience. 1989;29(3):503–37. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright CI, Beijer AV, Groenewegen HJ. Basal amygdaloid complex afferents to the rat nucleus accumbens are compartmentally organized. J Neurosci. 1996;16(5):1877–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01877.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zahm DS, Brog JS. On the significance of subterritories in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum. Neuroscience. 1992;50(4):751–67. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90202-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groenewegen HJ, Wright CI, Beijer AV. The nucleus accumbens: gateway for limbic structures to reach the motor system? Prog Brain Res. 1996;107:485–511. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mogenson GJ, Jones DL, Yim CY. From motivation to action: functional interface between the limbic system and the motor system. Prog Neurobiol. 1980;14(2–3):69–97. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(80)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennartz CM, Groenewegen HJ, Lopes da Silva FH. The nucleus accumbens as a complex of functionally distinct neuronal ensembles: an integration of behavioural, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42(6):719–61. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zahm DS, Heimer L. Specificity in the efferent projections of the nucleus accumbens in the rat: comparison of the rostral pole projection patterns with those of the core and shell. J Comp Neurol. 1993;8:327(2):220–32. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;28(3):309–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Floresco SB. Dopaminergic regulation of limbic-striatal interplay. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;2(6):400–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikemoto S, Panksepp J. The role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in motivated behavior: a unifying interpretation with special reference to reward-seeking. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;31(1):6–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicola SM. The flexible approach hypothesis: unification of effort and cue-responding hypotheses for the role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in the activation of reward-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2010;30(49):16585–600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3958-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar A, Mingote SM. Effort-related functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine and associated forebrain circuits. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191(3):461–82. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simerly RB, Swanson LW. The organization of neural inputs to the medial preoptic nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1986;246(3):312–42. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bridges RS, Robertson MC, Shiu RP, Friesen HG, Stuer AM, Mann PE. Endocrine communication between conceptus and mother: placental lactogen stimulation of maternal behavior. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;64(1):57–64. doi: 10.1159/000127098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Numan M, Rosenblatt JS, Komisaruk BR. Medial preoptic area and onset of maternal behavior in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91(1):146–64. doi: 10.1037/h0077304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen CA, Caldwell JD, Walker C, Ayers G, Mason GA. Oxytocin activates the postpartum onset of rat maternal behavior in the ventral tegmental and medial preoptic areas. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108(6):1163–71. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kita H, Oomura Y. An HRP study of the afferent connections to rat medial hypothalamic region. Brain Res Bull. 1982;8:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kocsis K, Kiss J, Csáki A, Halasz B. Location of putative glutamatergic neurons projecting to the medial preoptic area of the rat hypothalamus. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Numan M. Hypothalamic neural circuits regulating maternal responsiveness toward infants. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2006;5(4):163–90. doi: 10.1177/1534582306288790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Risold PY, Thompson RH, Swanson LW. The structural organization of connections between hypothalamus and cerebral cortex. Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:197–254. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saper C. Hypothalamic connections with the cerebral cortex. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:40–48. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vertes RP. Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse. 2004;51:32–58. doi: 10.1002/syn.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattson BJ, Morrell JI. Preference for cocaine- versus pup-conditioned contexts differentially engages neurons expressing either Fos or CART in lactating, maternal rodents. Neuroscience. 2005;135:315–328. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fleming AS, Suh EJ, Korsmit M, Rusak B. Activation of Fos-like immunoreactivity in the medial preoptic area and limbic structures by maternal and social interactions in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108(4):724–34. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lonstein JS, Simmons DA, Swann JM, Stern JM. Forebrain expression of c-fos due to active maternal behaviour in lactating rats. Neuroscience. 1998;82(1):267–81. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lonstein JS, De Vries GJ. Maternal behaviour in lactating rats stimulates c-fos in glutamate decarboxylase-synthesizing neurons of the medial preoptic area, ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and ventrocaudal periaqueductal gray. Neuroscience. 2000;100(3):557–68. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Numan M, Numan MJ, Marzella SR, Palumbo A. Expression of c-fos, fos B, and egr-1 in the medial preoptic area and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis during maternal behavior in rats. Brain Res. 1998;792(2):348–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Febo M, Numan M, Ferris CF. Functional magnetic resonance imaging shows oxytocin activates brain regions associated with mother-pup bonding during suckling. J Neurosci. 2005;25(50):11637–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3604-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferris CF, Kulkarni P, Sullivan JM, Jr, Harder JA, Messenger TL, Febo M. Pup suckling is more rewarding than cocaine: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging and three-dimensional computational analysis. J Neurosci. 2005;25(1):149–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3156-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lomber SG. The advantages and limitations of permanent or reversible deactivation techniques in the assessment of neural function. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;86(2):109–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin JH, Ghez C. Pharmacological inactivation in the analysis of the central control of movement. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;86(2):145–59. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Catterall WA, Mackie K. Local Anesthetics. In: Hardman JG, Limbard LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, Gilman A, editors. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 9. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. pp. 321–347. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hille B. Common mode of action of three agents that decrease the transient change in sodium permeability in nerves. Nature. 1966;210(5042):1220–2. doi: 10.1038/2101220a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hille B. The pH-dependent rate of action of local anesthetics on the node of Ranvier. J Gen Physiol. 1977;69(4):475–96. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.4.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boehnke SE, Rasmusson DD. Time course and effective spread of lidocaine and tetrodotoxin delivered via microdialysis: an electrophysiological study in cerebral cortex. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;105(2):133–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tehovnik EJ, Sommer MA. Effective spread and timecourse of neural inactivation caused by lidocaine injection in monkey cerebral cortex. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;74(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)02229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee A, Clancy S, Fleming AS. Mother rats bar-press for pups: Effects of lesions of the mpoa and limbic sites on maternal behavior and operant responding for pup-reinforcement. Behav Brain Res. 1999;100(1–2):15–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00109-0. Corrected and republished in: Behav Brain Res 2000;108(2):215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ågmo A, Gómez M. Sexual reinforcement is blocked by infusion of naloxone into the medial preoptic area. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107(5):812–818. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Band LC, Hull EM. Morphine and dynorphin(1–13) microinjected into the medial preoptic area and nucleus accumbens: effects on sexual behavior in male rats. Brain Res. 1990;524(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90494-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.García-Horsman SP, Agmo A, Paredes RG. Infusions of naloxone into the medial preoptic area, ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, and amygdala block conditioned place preference induced by paced mating behavior. Horm Behav. 2008;54(5):709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoshina Y, Takeo T, Nakano K, Sato T, Sakuma Y. Axon-sparing lesion of the preoptic area enhances receptivity and diminishes proceptivity among components of female rat sexual behavior. Behav Brain Res. 1994;61(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hughes AM, Everitt BJ, Herbert J. Comparative effects of preoptic area infusions of opioid peptides, lesions and castration on sexual behaviour in male rats: studies of instrumental behaviour, conditioned place preference and partner preference. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;102(2):243–256. doi: 10.1007/BF02245929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hull EM, Dominguez JM. Sexual behavior in male rodents. Horm Behav. 2007;52:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hurtazo HA, Paredes RG, Agmo A. Inactivation of the medial preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus by lidocaine reduces male sexual behavior and sexual incentive motivation in male rats. Neuroscience. 2008;152(2):331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kindon HA, Baum MJ, Paredes RJ. Medial preoptic/anterior hypothalamic lesions induce a female-typical profile of sexual partner preference in male ferrets. Horm Behav. 1996;30(4):514–527. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1996.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paredes RG, Highland L, Karam P. Socio-sexual behavior in male rats after lesions of the medial preoptic area: evidence for reduced sexual motivation. Brain Res. 1993;618(2):271–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91275-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paredes RG, Tzschentke T, Nakach N. Lesions of the medial preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus (MPOA/AH) modify partner preference in male rats. Brain Res. 1998;813(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00914-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sakuma Y. Neural substrates for sexual preference and motivation in the female and male rat. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:55–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Furth WR, Wolterink G, van Ree JM. Regulation of masculine sexual behavior: involvement of brain opioids and dopamine. Brain Res Rev. 1995;21(2):162–184. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(96)82985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xiao K, Kondo Y, Sakuma Y. Differential regulation of female rat olfactory preference and copulatory pacing by the lateral septum and medial preoptic area. Neuroendocrinology. 2005;81(1):56–62. doi: 10.1159/000084893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arrati PG, Carmona C, Dominguez G, Beyer C, Rosenblatt JS. GABA receptor agonists in the medial preoptic area and maternal behavior in lactating rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;87(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jacobson CD, Terkel J, Gorski RA, Sawyer CH. Effects of small medial preoptic area lesions on maternal behavior: retrieving and nest building in the rat. Brain Res. 1980;194(2):471–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miller SM, Lonstein JS. Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor antagonism in the preoptic area produces different effects on maternal behavior in lactating rats. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:1072–83. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.4.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Popeski N, Woodside B. Central nitric oxide synthase inhibition disrupts maternal behavior in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(6):1305–16. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.6.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vernotica EM, Rosenblatt JS, Morrell JI. Microinfusion of cocaine into the medial preoptic area or nucleus accumbens transiently impairs maternal behavior in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113(2):377–90. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heimer L, Alheid GF, de Olmos JS, Groenewegen HJ, Haber SN, Harlan RE, Zahm DS. The accumbens: beyond the core-shell dichotomy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9(3):354–81. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zahm DS. An integrative neuroanatomical perspective on some subcortical substrates of adaptive responding with emphasis on the nucleus accumbens. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(1):85–105. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sesack RS, Grace AA. Cortico-Basal ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology REVIEWS. 2010;35:27–47. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Floresco SB, St Onge JR, Ghods-Sharifi S, Winstanley CA. Cortico-limbic-striatal circuits subserving different forms of cost-benefit decision making. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2008;8(4):375–89. doi: 10.3758/CABN.8.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Phillips PEM, Walton ME, Thomas CJ. Calculating utility: preclinical evidence for cost-benefit analysis by mesolimbic dopamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:483–495. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. A role for mesencephalic dopamine in activation: commentary on Berridge (2006) Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:433–437. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brady AM, O’Donnell P. Dopaminergic modulation of prefrontal cortical input to nucleus accumbens neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2004;24(5):1040–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hansen S, Harthon C, Wallin E, Löfberg L, Svensson K. Mesotelencephalic dopamine system and reproductive behavior in the female rat: effects of ventral tegmental 6-hydroxydopamine lesions on maternal and sexual responsiveness. Behav Neurosci. 1991;105:588–98. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hansen S, Harthon C, Wallin E, Löfberg L, Svensson K. The effects of 6-OHDA-induced dopamine depletions in the ventral or dorsal striatum on maternal and sexual behavior in the female rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;39:71–7. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90399-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Keer SE, Stern JM. Dopamine receptor blockade in the nucleus accumbens inhibits maternal retrieval and licking, but enhances nursing behavior in lactating rats. Physiol Behav. 1999;67:659–69. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Numan M, Numan MJ, Pliakou N, Stolzenberg DS, Mullins OJ, Murphy JM, Smith CD. The effects of D1 or D2 dopamine receptor antagonism in the medial preoptic area, ventral pallidum, or nucleus accumbens on the maternal retrieval response and other aspects of maternal behavior in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119(6):1588–604. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.6.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Parada M, King S, Li M, Fleming AS. The roles of accumbal dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in maternal memory in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(2):368–76. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Silva MRP, Bernardi MM, Cruz-Casallas PE, Felicio LF. Pimozide injections into the nucleus accumbens disrupt maternal behaviour in lactating rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;93:42–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.930106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Champagne FA, Chretien P, Stevenson CW, Zhang TY, Gratton A, Meaney MJ. Variations in nucleus accumbens dopamine associated with individual differences in maternal behavior in the rat. J Neurosci. 2004;24(17):4113–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5322-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hansen S, Bergvall AH, Nyiredi S. Interaction with pups enhances dopamine release in the ventral striatum of maternal rats: a microdialysis study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;45(3):673–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90523-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Numan M, Stolzenberg DS. Medial preoptic area interactions with dopamine neural systems in the control of the onset and maintenance of maternal behavior in rats. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30(1):46–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seip KM, Morrell JI. Transient inactivation of the ventral tegmental area selectively disrupts the expression of conditioned place preference for pup- but not cocaine-paired contexts. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123(6):1325–1338. doi: 10.1037/a0017666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee KW, Kim Y, Kim AM, Helmin K, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Cocaine-induced dendritic spine formation in D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-containing medium spiny neurons in nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(9):3399–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511244103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Le Moine C, Bloch B. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor gene expression in the rat striatum: sensitive cRNA probes demonstrate prominent segregation of D1 and D2 mRNAs in distinct neuronal populations of the dorsal and ventral striatum. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355(3):418–26. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Le Moine C, Bloch B. Expression of the D3 dopamine receptor in peptidergic neurons of the nucleus accumbens: comparison with the D1 and D2 dopamine receptors. Neuroscience. 1996;73(1):131–43. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Deniau JM, Menetrey A, Thierry AM. Indirect nucleus accumbens input to the prefrontal cortex via the substantia nigra pars reticulata: a combined anatomical and electrophysiological study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1994;61(3):533–45. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maurice N, Deniau JM, Menetrey A, Glowinski J, Thierry AM. Position of the ventral pallidum in the rat prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuit. Neuroscience. 1997;80(2):523–34. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maurice N, Deniau JM, Glowinski J, Thierry AM. Relationships between the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia in the rat: physiology of the corticosubthalamic circuits. J Neurosci. 1998;18(22):9539–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09539.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maurice N, Deniau JM, Menetrey A, Glowinski J, Thierry AM. Prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits in the rat: involvement of ventral pallidum and subthalamic nucleus. Synapse. 1998;29(4):363–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199808)29:4<363::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maurice N, Deniau JM, Glowinski J, Thierry AM. Relationships between the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia in the rat: physiology of the cortico-nigral circuits. J Neurosci. 1999;19(11):4674–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Montaron MF, Deniau JM, Menetrey A, Glowinski J, Thierry AM. Prefrontal cortex inputs of the nucleus accumbens-nigro-thalamic circuit. Neuroscience. 1996;71(2):371–82. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Winn P, Brown VJ, Inglis WL. On the relationships between the striatum and the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1997;11(4):241–61. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v11.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]