Abstract

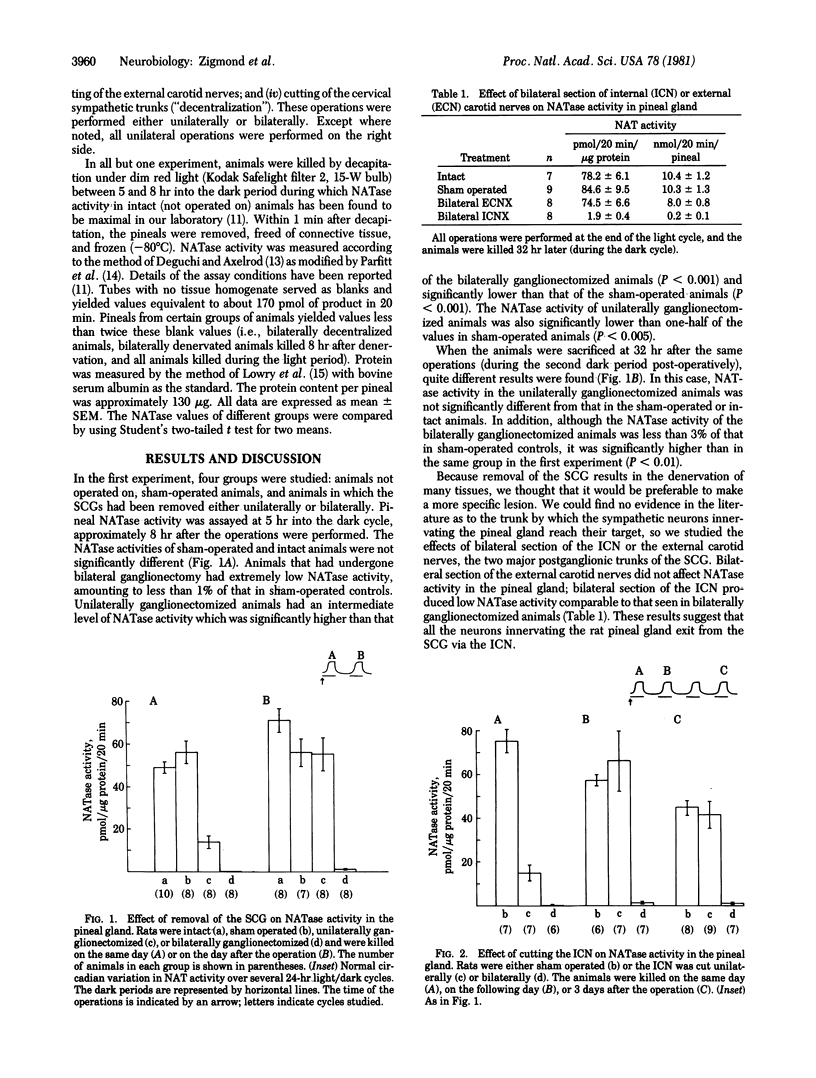

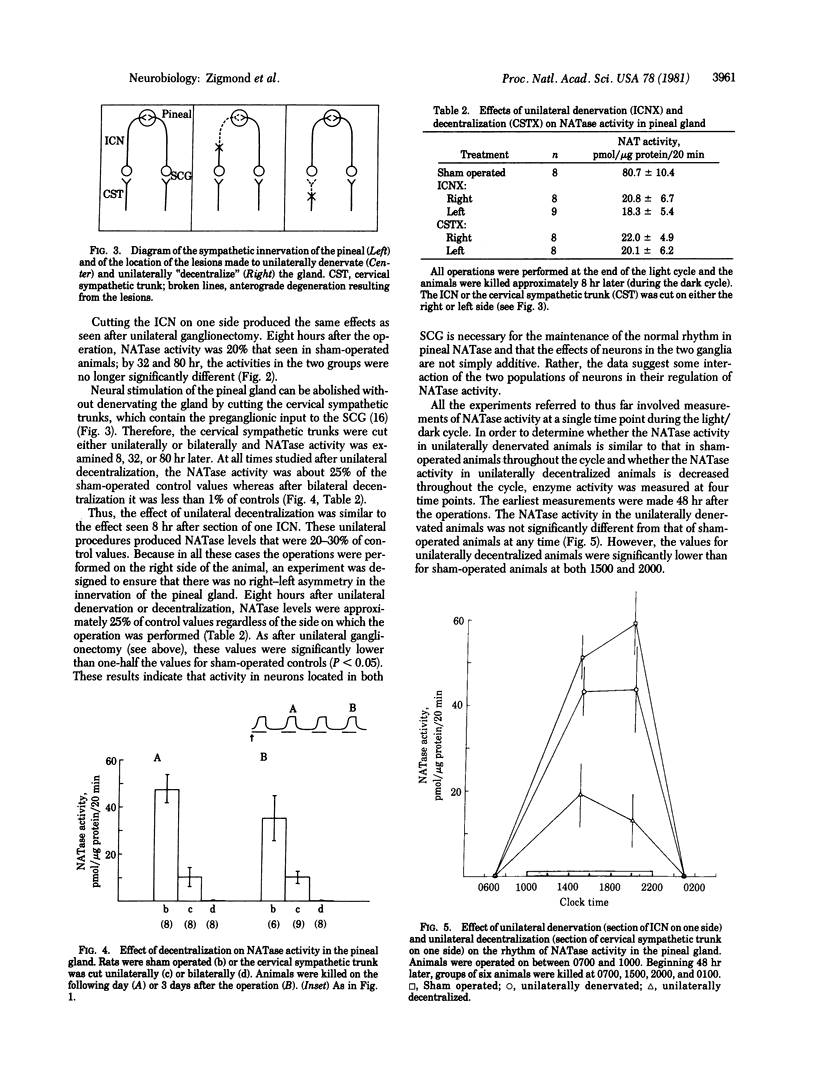

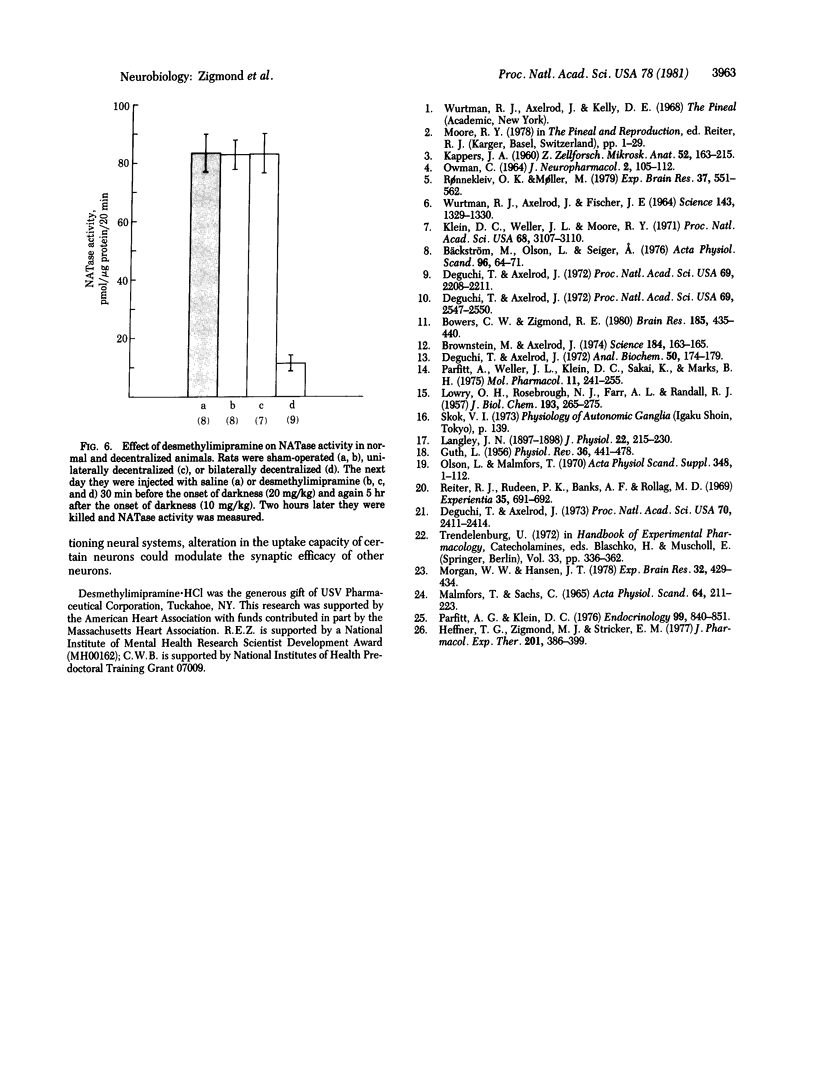

The activity of serotonin N-acetyltransferase (NATase) in the rat pineal gland exhibits a large (approximately 100-fold) circadian variation, with peak activity occurring in the dark part of the light/dark cycle. Surgical removal of both superior cervical ganglia abolishes this rhythm in enzyme activity. Unilateral ganglionectomy caused a 75% decrease in NATase activity during the dark period immediately following the operation; however, by the subsequent dark period (32 hr after operation) the rhythm in NATase activity had returned to normal. Similar results were found after the internal carotid nerve was cut, and data are presented indicating that this is the postganglionic trunk by which sympathetic neurons reach the pineal gland. Denervation of one superior cervical ganglion (unilateral "decentralization") also produced a 75% decrease in NATase activity during the dark period immediately following the operation; however, after decentralization, enzyme activity did not return to normal in subsequent cycles. It is hypothesized that this recovery is due to loss of norepinephrine uptake sites in the degenerating sympathetic nerve terminals. As a result of decreased norepinephrine uptake, the effectiveness of the norepinephrine released by surviving neurons may be enhanced. This hypothesis is supported by experiments in which pharmacological blockade of norepinephrine uptake in unilaterally decentralized animals increased NATase activity to control levels. We propose that neural systems which use transmitter uptake as the mechanism of transmitter inactivation have a built-in "reserve stimulatory capacity."

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bowers C. W., Zigmond R. E. Electrical stimulation of the cerivcal sympathetic trunks mimics the effects of darkness on the activity of serotonin:N-acetyltransferase in the rat pineal. Brain Res. 1980 Mar 10;185(2):435–440. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein M., Axelrod J. Pineal gland: 24-hour rhythm in norepinephrine turnover. Science. 1974 Apr 12;184(4133):163–165. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4133.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström M., Olson L., Seiger A. N-acetyltransferase and hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase activity in intraocular pineal transplants: diurnal thythm as evidence for functional sympathetic adrenergic innervation. Acta Physiol Scand. 1976 Jan;96(1):64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1976.tb10171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi T., Axelrod J. Control of circadian change of serotonin N-acetyltransferase activity in the pineal organ by the beta--adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972 Sep;69(9):2547–2550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.9.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi T., Axelrod J. Induction and superinduction of serotonin N-acetyltransferase by adrenergic drugs and denervation in rat pineal organ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972 Aug;69(8):2208–2211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.8.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi T., Axelrod J. Sensitive assay for serotonin N-acetyltransferase activity in rat pineal. Anal Biochem. 1972 Nov;50(1):174–179. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi T., Axelrod J. Supersensitivity and subsensitivity of the beta-adrenergic receptor in pineal gland regulated by catecholamine transmitter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Aug;70(8):2411–2414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.8.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUTH L. Regeneration in the mammalian peripheral nervous system. Physiol Rev. 1956 Oct;36(4):441–478. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1956.36.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner T. G., Zigmond M. J., Stricker E. M. Effects of dopaminergic agonists and antagonists of feeding in intact and 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977 May;201(2):386–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAPPERS J. A. The development, topographical relations and innervation of the epiphysis cerebri in the albino rat. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1960;52:163–215. doi: 10.1007/BF00338980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. C., Weller J. L., Moore R. Y. Melatonin metabolism: neural regulation of pineal serotonin: acetyl coenzyme A N-acetyltransferase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 Dec;68(12):3107–3110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.12.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley J. N. On the Regeneration of Pre-Ganglionic and of Post-Ganglionic Visceral Nerve Fibres. J Physiol. 1897 Nov 20;22(3):215–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1897.sp000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmfors T., Sachs C. Direct studies on the disappearance of the transmitter and changes in the uptake-storage mechanisms of degenerating adrenergic nerves. Acta Physiol Scand. 1965 Jul;64(3):211–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1965.tb04171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan W. W., Hansen J. T. Time course of the disappearance of pineal noradrenaline following superior cervical ganglionectomy. Exp Brain Res. 1978 Jul 14;32(3):429–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00238713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OWMAN C. SYMPATHETIC NERVES PROBABLY STORING TWO TYPES OF MONOAMINES IN THE RAT PINEAL GLAND. Int J Neuropharmacol. 1964 Apr;3:105–112. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(64)90052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L., Malmfors T. Growth characteristics of adrenergic nerves in the adult rat. Fluorescence histochemical and 3H-noradrenaline uptake studies using tissue transplantations to the anterior chamber of the eye. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1970;348:1–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt A. G., Klein D. C. Sympathetic nerve endings in the pineal gland protect against acute stress-induced increase in N-acetyltransferase (EC 2.3.1.5.) activity. Endocrinology. 1976 Sep;99(3):840–851. doi: 10.1210/endo-99-3-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt A., Weller J. L., Klein D. C., Sakai K. K., Marks B. H. Blockade by ouabain or elevated potassium ion concentration of the adrenergic and adenosine cyclic 3',5'-monophosphate-induced stimulation of pineal serotonin N-acetyltransferase activity. Mol Pharmacol. 1975 May;11(3):241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Rudeen P. K., Banks A. F., Rollag M. D. Acute effects of unilateral or bilateral superior cervical ganglionectomy on rat pineal N-acetyltransferase activity and melatonin content. Experientia. 1979 May 15;35(5):691–692. doi: 10.1007/BF01960402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rønnekleiv O. K., Møller M. Brain-pineal nervous connections in the rat: an ultrastructure study following habenular lesion. Exp Brain Res. 1979;37(3):551–562. doi: 10.1007/BF00236823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WURTMAN R. J., AXELROD J., FISCHER J. E. MELATONIN SYNTHESIS IN THE PINEAL GLAND: EFFECT OF LIGHT MEDIATED BY THE SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM. Science. 1964 Mar 20;143(3612):1328–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]