Abstract

Background

We have previously set up an in vitro mesenchymal-epithelial cell co-culture model which mimics the intestinal crypt villus axis biology in terms of epithelial cell differentiation. In this model the fibroblast-induced epithelial cell differentiation from secretory crypt cells to absorptive enterocytes is mediated via transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), the major inhibitory regulator of epithelial cell proliferation known to induce differentiation in intestinal epithelial cells. The aim of this study was to identify novel genes whose products would play a role in this TGF-β-induced differentiation.

Results

Differential display analysis resulted in the identification of a novel TGF-β upregulated mRNA species, the Sin3-associated protein 30-like, SAP30L. The mRNA is expressed in several human tissues and codes for a nuclear protein of 183 amino acids 70% identical with Sin3 associated protein 30 (SAP30). The predicted nuclear localization signal of SAP30L is sufficient for nuclear transport of the protein although mutating it does not completely remove SAP30L from the nuclei. In the nuclei SAP30L concentrates in small bodies which were shown by immunohistochemistry to colocalize with PML bodies only partially.

Conclusions

By reason of its nuclear localization and close homology to SAP30 we believe that SAP30L might have a role in recruiting the Sin3-histone deacetylase complex to specific corepressor complexes in response to TGF-β, leading to the silencing of proliferation-driving genes in the differentiating intestinal epithelial cells.

Background

The intestinal epithelium is a constantly renewing population of cells, which arise from the proliferating stem cells in the crypts of Lieberkuhn. In the intestinal mucosa the secretory crypt cells differentiate to absorptive enterocytes while migrating along the villus side to the villus tip. One of the most important modulators of intestinal epithelial cell differentiation is transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which affects the cell cycle machinery leading to terminal differentiation [1]. This acquisition of differentiated phenotype in epithelial cells requires finely tuned gene expression where the genes that drive proliferation are silenced while genes whose products are essential for a differentiated cell are activated.

We have previously shown by differential display PCR (DD-PCR) technique [2] that in a cell culture model, where differentiation of crypt-like T84 cells to enterocyte-like cells is induced by TGF-β [3] the changes in gene expression parallel those seen in differentiating intestinal epithelial cells in vivo [4]. In addition, a novel gene, apoptosis antagonizing transcription factor (AATF) (accession number HSA249940), whose expression was downregulated by TGF-β, was cloned from the undifferentiated crypt-like cells of the same cell culture system [5]. AATF is involved in epithelial cell proliferation, since it represses the growth suppression function of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb) [6] by inhibiting the recruitment of the histone deacetylase HDAC1 to the Rb/E2F complex [7].

The acetylation status of the histone proteins mainly responsible for the packing of chromatin plays a key role in transcriptional regulation. Acetylation of lysine residues in the histone tails is associated with a more open chromatin state and thus increased DNA accessibility to transcription factors [reviewed in [8]], while deacetylation or histone hypoacetylation is associated with tightly packed chromatin and transcriptional silencing [9,10]. Both transcriptional coactivators and corepressors regulate gene expression by influencing the histone acetylation status. Histone deacetylation is indeed a basic and well-conserved mechanism for gene silencing and it involves many corepressor proteins that vary depending on the repressor complex. The corepressor may well establish the target specificity of a given deacetylase complex as in the case of the Rb protein. It recruits a histone deacetylase complex to E2F transcription factors, leading to the repression of transcription of E2F-dependent target genes [11].

In this paper we now for the first time describe the initial characterization of another unknown transcript identified by DD-PCR in differentiating intestinal T84 epithelial cells. The newly identified gene codes for a protein markedly similar to the histone deacetylase-associated corepressor Sin3-associated protein 30 (SAP30), and therefore this novel Sin3-associated protein 30-like, SAP30L, could well have a role in silencing the genes crucial for proliferation in intestinal crypt epithelial cells.

Results

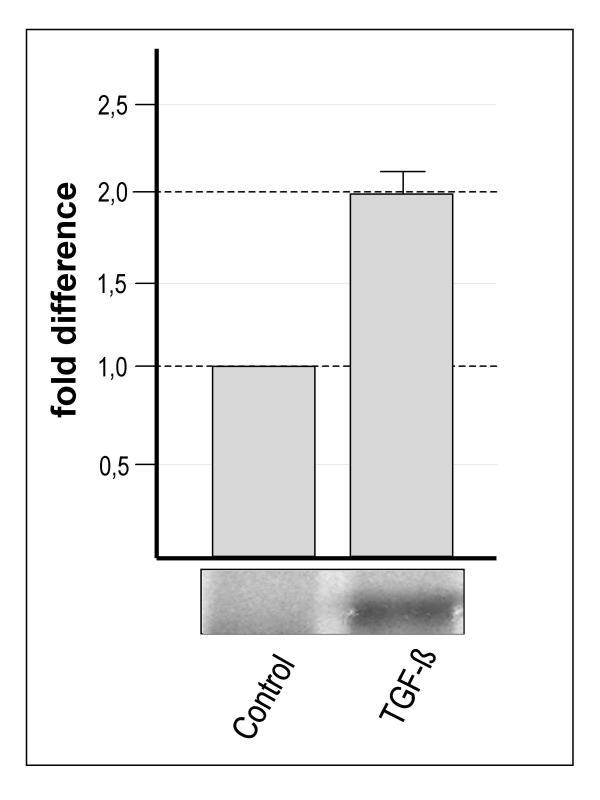

DD-PCR showed that TGF-β1 induced consistent and reproducible upregulation of a transcript denoted SAP30L (see later) (Figure 1) using the arbitrary 5' primer AP-3 and the 3' anchoring primer T12MG. Quantitative RT-PCR using LightCycler technology verified this induction by TGF-β in three independent experiments. The differentiated TGF-β-treated cells expressed this transcript 2.0 times more than the unstimulated T84 cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The expression of SAP30L in control and TGF-β-treated differentiated T84 epithelial cells. The lower panel shows that in DD-PCR the band representing SAP30L was present solely in the RNA sample from the differentiated T84 cells. Real time quantitative PCR verified this differential expression to be 2.0 times higher (SEM ± 0.13).

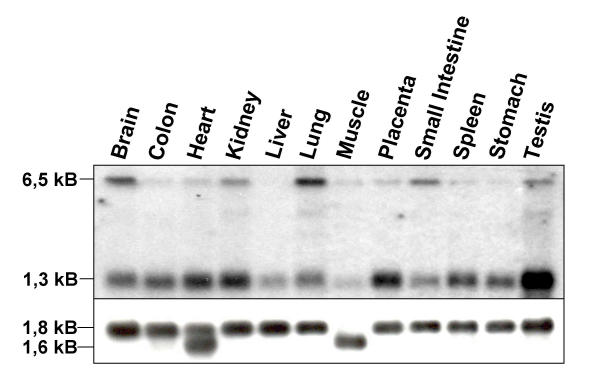

Sequence analysis of this transcript showed that SAP30L is identical with an mRNA transcribed from the gene FLJ11526 located in chromosome 5q33.2. The gene has four exons and the expected size of the transcribed mRNA is 1281 base pairs. Indeed, northern hybridization to a multi-tissue northern blot showed that a SAP30L-specific probe recognized an mRNA of approximately 1.3 kB (Figure 2). The mRNA was expressed in all tissues examined, with somewhat weaker expression in the liver and lung and particularly abundant expression in the testis. Interestingly, there was also a transcript of size 6.5 kB which was abundantly expressed in brain and lung but not at all in liver and stomach. As the genomic sequence did not predict an mRNA of this size, its identity remains to be established.

Figure 2.

SAP30L mRNA expression in human tissues. Northern hybridization to a multi-tissue northern blot showed that a 1.3 kB transcript is expressed in all tissues examined, with higher expression in the testis and weaker in the liver and lung. A transcript of size 6.5 kB was abundantly expressed in brain and lung but not at all in liver and stomach. The lower panel shows the control hybridization with an β-actin specific probe.

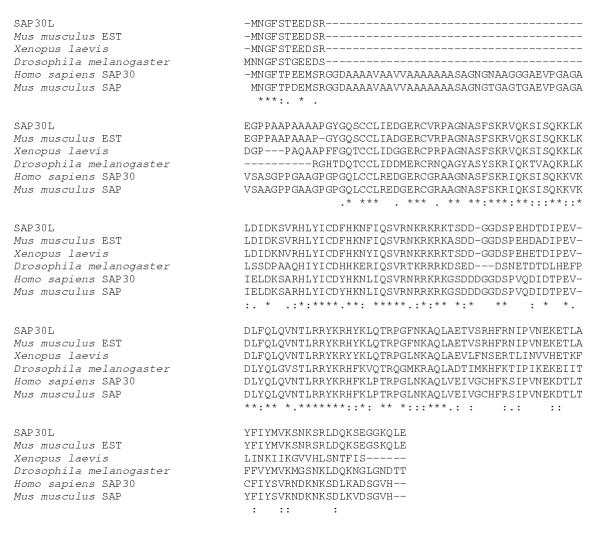

Screening of a heart cDNA library in order to find the whole-length transcript resulted in identification of a positive clone with an insert of size 1.3 kB. When the clone was sequenced and compared to the sequence of an Image clone FLJ11526, the two sequences were found to be identical. Both clones code for a protein of 183 amino acids (Figure 3), which was named Sin3-associated protein 30 like, SAP30L. Prosite scan identified two putative N-glycosylation sites (NASF, amino acids 44–47 and NKSR, amino acids 168–171), one N-myristoylation site (GQSCCL, amino acids 26–31) and several phosphorylation sites for different kinases. The PsortII program predicted the SAP30L protein to be nuclear, the putative nuclear localization signal being KRKRK, ranging from amino acid 87 to 91 (Figure 3). A database search for homologous proteins showed that SAP30L has orthologues in several species (Figure 4). The corresponding mouse protein is 97% identical with the human SAP30L. The Xenopus protein is 85% identical along the first 150 amino acids after which they begin to diversify considerably while the Drosophila melanogaster orthologue is fairly identical along the whole protein, the identity being 52%. Interestingly, there was a human protein called SAP30, which was 70% identical with SAP30L. Amino acid comparison of SAP30L with SAP30 showed SAP30 to have in its N-terminus a 38-amino-acid stretch that was absent in SAP30L. The corresponding SAP30 protein was also found in mouse but not in other species.

Figure 3.

The amino acid sequence of SAP30L. SAP30L had an open reading frame of 183 amino acids. The PsortII-predicted N-glycosylation sites are in italics, the N-myristoylation site is underlined and the nuclear localization signal is boxed.

Figure 4.

Multiple alignment of SAP30L with its orthologues and SAP30 proteins of human and mouse. All six proteins are highly identical except for the 38 amino acids which appear in SAP30 of human, and mouse. Asterisks mark identical amino acids, colons and periods designate conservative substitutions.

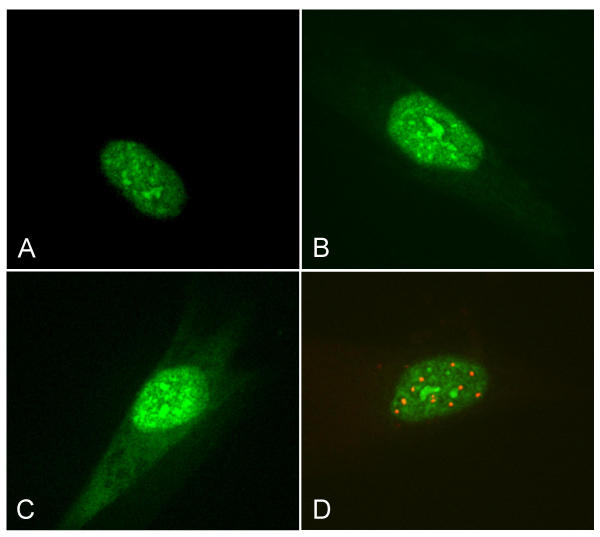

In transient transfection experiments on IMR-90 fibroblasts we were able to show that the wild-type SAP30L-EGFP fusion protein is indeed nuclear and concentrates in small dense bodies (Figure 5a). The transfection of the EGFP fusion protein, which had only the putative nuclear localization and six flanking amino acids on either side (pEGFP-NLS), also resulted in the nuclear localization of the protein (Figure 5b), thus providing evidence for the functionality of the signal. Mutation in the nuclear localization signal (NLS) (KRKRK → KSNRK) disturbed this nuclear localization to some extent, causing the protein to be visible also in the cytosol although it did not completely inhibit the protein's nuclear transport (Figure 5c). Immunocytochemical staining of these transfected cells with anti-promyelotocytic leukaemia (PML) antibody showed these nuclear structures to be other than PML bodies (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Transfection of the different EGFP fusion constructs to IMR-90 fibroblasts. A) The wild-type SAP30L concentrates in small dense bodies in the nuclei. B) The nuclear localization of the fusion protein with only the NLS of SAP30L provides evidence for the functionality of the nuclear localization signal. C) Mutating the NLS disrupts the nuclear localization of the protein to some extent. D) Anti-PML-antibody staining (red) of wild-type SAP30L-transfected cells shows that the nuclear concentrates are other than PML bodies.

Discussion

We describe here the cloning of a novel human TGF-β-upregulated mRNA from differentiated T84 epithelial cells. The novel mRNA is approximately 1.3 kB long and was ubiquitously expressed in all tissues examined. The protein, called SAP30L, is 183 amino acids in length and located in the nucleus, where it concentrates in small dense structures other than PML bodies.

SAP30L protein is 70% identical to a protein called SAP30, the most prominent difference being the lack of 38 amino acids in the N terminus of SAP30L. At the genomic level, although their DNA sequences differ, their exon-intron organization is exactly the same, which suggests a common evolutionary origin for these genes. It would appear that SAP30L is evolutionarily older than SAP30, since only mammals have the protein with the extra 38 N-terminal amino acids. The size of for example the Drosophila orthologue corresponds better with the size of SAP30L than with SAP30.

Based on the extremely high degree of identity in the primary structure of SAP30L and SAP30 it is probable that they also share functional similarity. SAP30 is a 30 kD nuclear protein associated with the Sin3 corepressor complex [12,13], which contains at least mSin3, HDAC1 and 2, SAP18, RbAp46 and RbAp48 proteins [14]. The Sin3 complex facilitates transcriptional repression by being recruited to specific sites by different DNA-binding transcription factors [15,16] such as Mad, Ikaros, p53 and nuclear hormone receptors [17]. SAP30 is involved in the interaction at least in the case of nuclear hormone receptors, where it is thought to act as a specificity factor stabilizing or facilitating the interaction between the DNA-binding N-CoR and Sin3A [14]. SAP30 binds to N-CoR by its 129 N-terminal amino acids and to Sin3 with amino acids 129–220 [14]. Since the C-terminal part of SAP30L and SAP30 are markedly similar but SAP30L lacks 38 amino acids in the N-terminus when compared to SAP30, SAP30L is likely to bind Sin3A but not N-CoR. Further evidence for the binding of SAP30L to mSin3a comes from a recent study by Fleischer and associates [18] where they identified a novel 28 kD protein which binds to mSin3a. The identified protein is very probably SAP30L. In the Sin3 repressor complex SAP30L might work similarly to SAP30 eg to recruit Sin3a to other repressor complexes than N-CoR.

The recruitment of the Sin3-HDAC repressor complex to E2-dependent promoters leads to exit from the cell cycle, thus allowing differentiation to occur [19]. TGF-β promotes exit from cell cycle in many ways, for example by directly inhibiting the expression of c-myc [20], which is mediated by proteins E2F4/5, Smads and p107 [21]. P107 is a pocket protein able to bind to HDACs. It is interesting to speculate that SAP30L could be upregulated by TGF-β in order to fulfil its role in the stabilization of the Sin3 repressor complex in E2F-dependent promoter sites to repress transcription of proliferation-associated genes such as c-myc and may thus have a crucial role in differentiation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report here the identification of a novel transcript, SAP30L, which encodes a protein that very likely has a role in a histone deacetylase complex. Since the protein is 70% identical with a previously known protein SAP30 it might function similarly to SAP30, e.g. in recruiting Sin3A to a specific repressor complex other than N-CoR, leading to the silencing of proliferation-driving gene(s) and ultimately to the differentiation of the intestinal epithelial cells.

Methods

Cell lines and cultures

Human intestinal epithelial T84 cells (CCL 248) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium and Ham's F-12 (1:1) (Gibco BRL, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 5% foetal calf serum (FCS) and antibiotics (500 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin; Gibco BRL). Three-dimensional type I collagen gel cultures were conducted as previously described [3]. Differentiation of T84 cells was induced by adding 20 ng/ml of human recombinant TGF-β1 (hTGF-β1, R&D Systems Europe, Oxon, UK) to the cultures and the cultures were kept in 5% CO2 at 37°C for seven days.

The human embryonic lung fibroblast cell line IMR-90 (CCL 186) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The cells were cultured in basal medium (Eagle) supplemented with 10% FCS, 0.075% NaHCO3 and 2 mmol/l glutamine.

RNA isolation and differential display PCR

Total RNA was isolated from control and hTGF-β1-treated three-dimensionally cultured T84 cells with TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL) as instructed by the manufacturer and subjected to DNase I (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) treatment, after which they were extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). DD-PCR was done according to the RNAmap™ protocol (GenHunter Corporation, Nashville, TN) with arbitrary 5' primers and anchoring 3' primers. The reactions were repeated twice with newly purified RNA in order to confirm the reproducibility of the results. The differentially expressed transcripts were recovered from the gel and sequenced using the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) as instructed by the manufacturer.

Primers

The primers used in different experiments are shown in Table 1 and were purchased from either Genset Oligos (Paris, France) or TAG Copenhagen (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Table 1.

Primers used in the study.

| Primer | Sequence (5'→3') | Method | Company |

| FLJforward | CCCAAGCTTGGGGCGGGGAGATGAACGGCTTC | EGFP-PCR | Genset Oligos |

| FLJreverse | CCGGAATTCTCAAGCTGCTTGCCACCCTCCGA | EGFP-PCR | Genset Oligos |

| EX1S | AGCACGGAGGAGGACAGCCGCGAA | Sequencing | Genset Oligos |

| EX2S | GTAAGGCACCTATATATCTGTGAT | Sequencing | Genset Oligos |

| EX2AS | GTGTCGTGCTCGGGAGAATCTCCG | Sequencing | Genset Oligos |

| EX3S | GTTGATCTGTTCCAGCTGCAGGTG | Library screening LightCycler Northern probe |

Genset Oligos |

| EX3AS | TTCTGCTAACTGGGCCTTATTGAA | Sequencing | Genset Oligos |

| EX4AS | TCAAGCTGCTTGCCACCCTCCGA | Library screening LightCycler Northern probe |

Genset Oligos |

| 3G3TNLSfor | CGAAATAAAAGTAACAGGAAGACAAGT | NLS mutation | TAG Copenhagen |

| 3G3TNLSrev | ACTTGTCTTCCTGTTACTTTTATTTCG | NLS mutation | TAG Copenhagen |

The table indicates the names and sequences of the primers used in given experiments.

Quantitative PCR

Differential expression was confirmed using LightCycler technology in three independent RNA populations. One microgram of the Dnase I-treated total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL) with 0.5 μg of oligo(dT) primer. This cDNA was then subjected to PCR using a LightCycler Fast Start Cyber Green kit (Roche Diagnostics, Espoo, Finland) according to manufacturer's instructions. The primers 3EX3S and 3EX4AS (see Table 1) were used at a concentration of 0.5 μM. The cycling conditions were as follows; 96C 10 min followed by 45 cycles at 96C 10 s, 57C 10 s and 72C 10 s. The relative amounts of the unknown samples (control and TGF-β treated) were calculated by setting their cross points to the standard curve generated by a serial dilution of cDNA produced from T84 cells. The expression level of SAP30L in undifferentiated and differentiated T84 cells was normalized by the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase.

Screening of cDNA library for the whole length transcript

A human heart cDNA library (Rapid-Screen Arrayed cDNA Library Panel; OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD) was screened by PCR using primers 3EX3S and 3EX4AS. The conditions of the PCR amplification for both Master Plate and Sub-plates were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 45 s, annealing at 57°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 60 s with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. For the third round of screening, PCR was performed on single bacterial colonies. DNA from positive clones was sequenced using both vector- and gene-specific primers indicated in the table. The accession number for SAP30L is AY341060

Northern hybridization

A SAP30L specific PCR fragment was labelled with [α-32P]dATP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Amersham, UK) using Strip-Ez DNA™ Random Primed StribAble™ DNA probe synthesis and removal kit (Ambion, Austin, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions and hybridised to human 12 tissue northern blot (Origene Technologies). A β-actin specific probe served as a positive control.

Sequence analysis

The nucleic acid sequence and the deduced amino acid sequence were searched against the NCBI Blast database [22]. PSORTII server [23] was used to predict the subcellular localization of the SAP30L protein and to identify the putative peptide responsible for this localization.

Construction of EGFP expression vectors and transfection

Wild-type SAP30L cDNA was cloned into the pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto CA) expression vector by polymerase chain reaction using primers (Table 1) with EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites at the 5'- and 3' ends, respectively. The mutation to the putative nuclear localization signal was generated by PCR using two complementary oligos (Table 1) bearing the mutated sequence (R88→S and K89→N) and the previously mentioned primers with EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites for cloning the insert into the EGFP vector. In addition, for generation of the pEGFP-NLS construct a double-stranded oligo containing the predicted consensus nuclear localization signal plus six flanking amino acids on either terminus was ordered from TAG Copenhagen and cloned into pEGFP-C1.

5 × 104 cells were plated on chamber slides (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) and cultured for 24 hours prior to transfection with 1 μg of the appropriate EGFP construct and Tfx-50 reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) for 2 hour. Detection of the green fluorescence protein by confocal microscopy (Ultraview Confocal Imaging System, PerkinElmer Life Sciences Inc., Boston, MA) was performed 24 hours after transfection.

Immunocytochemistry

Expression of the PML protein in transfected IMR-90 fibroblasts was detected using a commercial antibody PG-M3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA). The transfected cells were fixed with methanol 24 hours after transfection, whereafter the non-specific binding of antibodies was blocked with normal serum. The anti-PML-antibody was diluted 1:50 and incubated for one hour. The TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse secondary serum (1:200) (Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) was incubated for an hour before the slides were dried and mounted with 50% glycerol in PBS. To assess the overlapping of the EGFP-emitted green and TRITC-emitted red fluorescence the slides were studied under a confocal microscope and the images were merged.

Abbreviations

TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; DD-PCR, differential display PCR; AATF, apoptosis antagonising transcription factor; Rb, retinoblastoma; SAP30, Sin3-associated protein 30; SAP30L, Sin3-associated protein 30-like; PML, promyelocytic leukaemia; FCS, foetal calf serum

Authors' contributions

KL performed the differential display analysis, analyzed the sequences and constructed the EGFP fusion vectors and participated in the transfections, immunocytochemical stainings and also in the design of the study. She also wrote the manuscript. KMV performed the transfection experiments and the immunohistochemical stainings. MN carried out the real-time quantitative PCR, screened the cDNA library for the whole-length transcript and performed the northern hybridization. TYKH participated in the sequence analysis and library screening. MM and HK conceived, coordinated and designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jorma Kulmala for technical assistance.

The Coeliac Disease Study Group is supported by the Academy of Finland Research Council for Health, funding decision numbers 73489 and 201361, the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, the Foundation of the Friends of the University Children's Hospitals in Finland, the Foundation for Paediatric Research in Finland, the Medical Research Fund of Tampere University Hospital and the Commission of the European Communities, specific RTD programme "Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources", QLK1-CT-1999-00037, "Evaluation of the prevalence of coeliac disease and its genetic components in the European population". The study does not necessarily reflect the Commission's views and in no way anticipates its future policy in this area.

Contributor Information

Katri Lindfors, Email: katri.lindfors@uta.fi.

Keijo M Viiri, Email: keijo.viiri@uta.fi.

Marjo Niittynen, Email: marjo.niittynen@ktl.fi.

Taisto YK Heinonen, Email: taisto.heinonen@uta.fi.

Markku Mäki, Email: markku.maki@uta.fi.

Heikki Kainulainen, Email: heikki.kainulainen@uta.fi.

References

- Dignass A, Tsunekawa S, Podolsky D. Fibroblast growth factor modulates epithelial cell growth and migration. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Pardee A. Differential display of eukaryotic messenger RNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science. 1992;257:967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halttunen T, Marttinen A, Rantala I, Kainulainen H, Mäki M. Fibroblasts and transforming growth factor-beta induce organization and differentiation of T84 human epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1252–1262. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindfors K, Halttunen T, Kainulainen H, Mäki M. Differentially expressed CC3/TIP30 and rab11 along in vivo and in vitro intestinal epithelial cell crypt-villus axis. Life Sciences. 2001;69:1363–72. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindfors K, Halttunen T, Huotari P, Nupponen NN, Vihinen M, Visakorpi T, Mäki M, Kainulainen H. Identification of novel transcription factor-like gene from human intestinal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 2000;276:660–666. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanciulli M, Bruno T, Di Padova M, De Angelis R, Iezzi S, Iacobini C, Floridi A, Passananti C. Identification of a novel partner of RNA polymerase II subunit 11, Che-1, which interacts with and affects the growth suppression function of Rb. FASEB J. 2000;14:904–912. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.7.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno T, De Angelis R, De Nicola F, Barbato C, Di Padova M, Corbi N, Libri V, Benassi B, Mattei E, Chersi A, Saddu S, Floridi A, Passananti C, Fanciulli M. Che-1 affects cell growth by interfering with the recruitment of HDAC1 by Rb. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein M, Rose AB, Holmes SG, Allis CD, Broach JR. Transcriptional silencing in yeast is associated with reduced nucleosome acetylation. Genes De. 1993;7:592–604. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BM. Decoding the nucleosome. Cell. 1993;75:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira R, Naguibneva I, Mathieu M, Ait-Si-Ali S, Robin P, Pritchard LL, Harel-Bellan A. Cell cycle-dependent recruitment of HDAC-1 correlates with deacetylation of histone H4 on an Rb-E2F target promoter. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:794–799. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassig CA, Fleischer TC, Billin AN, Schreiber SL, Ayer DE. Histone deacetylase activity is required for full transcriptional repression by mSin3A. Cell. 1997;89:341–347. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Iratni R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone deacetylases and SAP18, a novel polypeptide, are components of the human Sin complex. Cell. 1997;89:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laherty CD, Billin AN, Lavinsky RM, Yochum GS, Bush AC, Sun J-M, Mullen T-M, Davie JR, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfield MG, Ayer DE, Eisenman RN. SAP30, a component of the mSin3 corepressor complex involved in N-CoR-mediated repression by specific transcription factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadosh D, Struhl K. Repression by Ume6 involves recruitment of a complex containing Sin3 corepressor and Rpd3 histone deacetylase to target promoters. Cell. 1997;89:365–371. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundlett SE, Carmen AA, Suka N, Turner BM, Grunstein M. Transcriptional repression by UME6 involves deacetylation of lysine 5 of histone H4 by RPD3. Nature. 1998;392:831–835. doi: 10.1038/33952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfler PS, Eisenman RN. Sin meets NuRD and other tails of repression. Cell. 1999;99:447–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer TC, Yun UI, Ayer DE. Identification and characterization of three new components of the mSin3a corepressor complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3456–3467. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3456-3467.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A, Kennedy BK, Barbie DA, Bertos NR, Yang XJ, Theberge MC, Tsai SC, Seto E, Zhang Y, Kuzmichev A, Lane WS, Reinberg D, Harlow E, Branton PE. RBP1 recruits the mSIN3-histone deacetylase complex to the pocket of retinoblastoma tumour suppressor family proteins found in limited discrete regions of the nucleus at growth arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2918–2932. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2918-2932.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane J, Pouponnot C, Staller P, Schader M, Eilers M, Massague J. TGFβ influences Myc, Miz and Smad to control the CDK inhibitor p15Ink4b. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:400–408. doi: 10.1038/35070086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-R, Kang Y, Siegel PM, Massague J. E2F4/5 an p107 as Smad cofactors linking the TGFβ receptor to c-myc repression. Cell. 2002;110:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00801-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden T, Schaffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai K, Kanehisa M. A knowledge base for predicting protein localization sites in eukaryotic cells. Genomics. 1992;14:897–911. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]