Abstract

TAR DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43) plays a central role in the neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD-TDP) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, but the relationship between TDP-43 abnormalities and Alzheimer disease (AD) remains unclear. To determine whether TDP-43 can serve as a neuropathological marker of AD, we performed biochemical characterization and quantification of TDP-43 in homogenates from parietal neocortex of subjects with a clinical diagnosis of no cognitive impairment (NCI, n = 12), mild cognitive impairment (MCI, n = 12), or AD (n = 12). Immunoblots revealed increased detergent-insoluble TDP-43 in the cortex of 0/12, 3/12 and 6/12 individuals with NCI, MCI or AD, respectively. Detergent-insoluble TDP-43 was positively correlated with the accumulation of soluble Aβ42, amyloid plaques and paired helical filament tau. In contrast, phospho-TDP-43 was decreased in the cytosolic fraction and detergent-soluble membrane/nuclear fraction from AD patients and correlated with antemortem cognitive function. Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed that the frequencies of individuals with TPD-43 or phospo-TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions were higher in AD than in NCI, with MCI at an intermediate level. These data indicate that abnormalities of TDP-43 occur in an important subset of MCI and AD patients and that they correlate with the clinical and neuropathological features of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Amyloid, Human, Immunoblot, Mild cognitive impairment, tau, TDP-43

Introduction

Transactive response (TAR) DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43) proteinopathy is one of the rapidly evolving topics in neurodegenerative disease research. This protein, which is normally found in the cell nucleus, is the major component of the ubiquitin-positive neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions that are hallmarks of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions (FTLD-U, now designated FTLD-TDP) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) without superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) mutation (1-6). Since 2008, at least 38 mutations in the gene encoding TDP-43 have been found in people with familial and sporadic ALS and FTLD-TDP, supporting a causative role of TDP-43 in the neurodegenerative processes underlying these diseases (7, 8). Most forms of sporadic ALS and FTLD-TDP are now collectively referred to as TDP-43 proteinopathies (7, 9, 10).

TDP-43 is a DNA- and RNA-binding protein that is normally found in the nucleus and is involved in the regulation of gene expression by controlling several processes, including gene transcription, RNA splicing, mRNA stabilization and transport, miRNA binding and regulation (11-13). The pathogenicity of TDP-43 involves the perturbation of its trafficking between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, where it becomes sequestered as insoluble aggregates (7, 14, 15). Indeed, nuclear staining of TDP-43 is significantly reduced in neurons that bear cytoplasmic ubiquitin-positive inclusions (3, 5, 16). Moreover, pathological TDP-43 is cleaved to generate ubiquitinated and hyperphosphorylated 35 and 25 kD C-terminal fragments (17, 18).

The relationship between TDP-43 and Alzheimer disease (AD) has not yet been clearly defined. Qualitative analyses report the presence of TDP-43 immunostained aggregates in between 14 and 57% of AD brains examined (19-30), and even up to 75% in advanced stage AD patients (27). Using antibodies specifically targeting phosphorylated and/or C-terminal fragments, TDP-43-positive cytoplasmic inclusions can be detected in brain sections from AD cases (22, 27, 30); however, these studies used qualitative immunohistochemical and histological techniques and did not distinguish between soluble and insoluble protein fractions.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a general term used to describe mild cognitive deficits of insufficient severity to warrant a diagnosis of dementia in elderly people; in many cases this represents an early sign of developing AD (31). The neuropathological substrate of MCI is not well defined due to the low availability of brain samples from individuals who died at the time they suffered from the condition. Nevertheless, most studies report that individuals with MCI show levels of β-amyloid (Aβ) and tau pathologies at intermediate levels between AD and controls (32-34). To our knowledge, no quantitative assessment of the accumulation of TDP-43 in preclinical AD has been performed.

Clinicopathologic studies have established the importance of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary pathology in AD, but have also revealed imperfections in the correlation between Aβ and tau and cognitive decline (35-38). Although the complexity of the disease may explain these inconsistencies, it is conceivable that other neuropathological events contribute significantly to the AD. To determine whether TDP-43 can be considered a neuropathological marker of AD and/or MCI in comparison with Aβ and tau, we performed biochemical quantification of TDP-43 in brain homogenates from individuals with AD or MCI. Biochemical data were also correlated with qualitative analysis of TPD-43 and phospo-TDP-43 cytoplasmic immunofluorescence. Our principal aim was to investigate the relationship between clinical diagnosis, antemortem cognitive function, the extent of Aβ and tau neuropathology and the accumulation of TDP-43 in the parietal cortex.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-actin (ABM, Richmond, Canada), anti-tau 13 (Covance, Princeton, NJ), anti-tau CP-13 (phosphorylated at serine 202/threonine 205, gift from Dr Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY), anti-C-TDP-43 (12892 polyclonal antibody to C-terminal TDP-43, Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL), anti-TDP-43 2E2-D3 (human-specific monoclonal antibody to total TDP-43, Abnova, Walnut, CA [39]), anti-N-TDP-43 (polyclonal antibody to N-terminal TDP-43, Cosmo Bio, Carlsbad, CA), anti-TDP-43 pS403/S404 (polyclonal antibody to phosphorylated serine 403/serine 404 TDP-43, Cosmo Bio), anti-TDP-43 pS409/S410 (polyclonal antibody to phosphorylated serine 409/serine 410 TDP-43, Cosmo Bio) and anti-tubulin (ABM). All biochemical reagents were purchased from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ) unless otherwise specified.

Study Participants

Brain cortex samples were obtained from participants in the Religious Order Study, a longitudinal clinical-pathologic study of aging and dementia from which an extensive amount of clinical and neuropathological data were available (40). The Study included participants with the clinical diagnosis of MCI (n = 12), AD (n = 12), and persons with no obvious cognitive impairment (NCI, n = 12), as previously described (32). Each participant had undergone uniform structured baseline clinical evaluation and annual follow-up evaluation until death (33). Briefly, dementia and AD diagnosis required evidence of meaningful decline in cognitive function and impairment on at least 2 cognitive domains (for AD, 1 domain had to have been episodic memory), based on the results of 21 cognitive performance tests and their review by a clinical neuropsychologist and expert clinician. “MCI” refers to participants with cognitive impairment as assessed by the neuropsychologist but without a diagnosis of dementia, as determined by the clinician. At death, a neurologist, blinded to all postmortem data, reviewed all available clinical data and rendered a summary diagnostic opinion regarding the clinical diagnosis at the time of death (41-43).

At death, each case was assigned a Braak score based on neuronal neurofibrillary tangle pathology (44), a neuritic plaque score based on modified the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer Disease (CERAD) criteria (excluding age and clinical diagnosis), and an AD pathologic diagnosis based on the National Institute on Aging-Reagan criteria, by examiners blinded to all clinical data (33). Neuritic plaques, diffuse plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles in the inferior parietal cortex were counted following Bielschowsky silver staining, as previously described (45). Concentrations of Aβ and tau in the parietal cortex were assessed using ELISA and Western immunoblotting, as described (32). Table 1 summarizes clinical and neuropathological data of subjects grouped by the clinical diagnosis. A global measure of cognition was attributed to each patient based on 19 cognitive performance tests and could also be summarized as cognitive abilities in 5 domains: episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual speed, and visuospatial ability (46).

Table 1. Selected Characteristics of Subjects From the Religious Order Study with a Clinical Diagnosis of No Cognitive Impairment, Mild Cognitive Impairment or Alzheimer Disease.

| Characteristics | NCI | MCI | AD | Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| Men, % | 8.4 | 50 | 25 | C; Pearson test, c2 = 5.26; p = 0.07 |

| Mean age at death | 85.0 (6.0) | 84.5 (3.8) | 86.1 (5.8) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 0.29; p = 0.75 |

| Mean education, y (SD) | 17.5 (3.9) | 19.6 (2.4) | 18.0 (2.8) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 1.49; p = 0.24 |

| Mean MMSE (SD) | 27.4 (2.0) | 26.9 (2.2) | 16.2 (8.9)a | A; F(group)2,33 = 16.57; p < 0.0001 |

| Global cognition score (SD) | -0.12 (0.23) | -0.43 (0.46) | -1.75 (0.96)a | A; F(group)2,32 = 22.22; p < 0.0001 |

| Time since last MMSE, days | 276 (327) | 237 (191) | 281 (80) | A; F(group)2,32 = 0.25; p = 0.77 |

| apoE e4 allele carriage, % | 25 | 33 | 50 | C; Pearson test, c2 = 1.69; p = 0.43 |

| Cerebellar pH (SD) | 6.36 (0.31) | 6.46 (0.21) | 6.49 (0.37) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 0.62; p = 0.55 |

| Post mortem delay, hours (SD) | 7.4 (6.4) | 6.0 (4.1) | 6.3 (3.9) | A; F(group)2,32 = 0.19; p = 0.83 |

| Aβ IHC density (SD) | 0.9 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.7) | 4.7 (3.0)b | A; F(group)2,22 = 7.66; p = 0.003 |

| PHFtau IHC density (SD) | 1.0 (2.6) | 4.0 (7.3) | 26.8 (35.5)c | A; F(group)2,27 = 4.59; p = 0.019 |

| Neuron Plaque Counts (SD) | 2.3 (2.8) | 4.7 (4.3) | 25.9 (26.5)d | A; F(group)2,33 = 8.12; p = 0.0014 |

| Neuron Diffuse Plaque Counts (SD) | 12.3 (23.8) | 22.8 (26.2) | 20.4 (17.2) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 0.69; p = 0.51 |

| Aβ40 concentration (soluble) (SD) | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.6) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 0.90; p = 0.42 |

| Aβ40 concentration (insoluble) (SD) | 1.9 (4.0) | 0.2 (0.6) | 20.42 (17.22) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 1.24; p = 0.30 |

| Aβ42 concentration (soluble) (SD) | 4.5 (4.5) | 5.9 (7.0) | 0.8 (2.3) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 1.93; p = 0.16 |

| Aβ42 concentration (insoluble) (SD) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.6)e | A; F(groups)2,33 = 4.65; p = 0.015 |

| Total tau content (soluble) (SD) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | A; F(groups)2,33 = 2.51; p = 0.10 |

| Total tau content (insoluble) (SD) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.9(0.7) | 1.5 (0.9)b | A; F(groups)2,33 = 5.46; p = 0.009 |

| Total PHFtau content (insoluble) (SD) | 3.7 (2.8) | 8.8 (13.0) | 29.1 (37.2)c | A; F(groups)2,33 = 4.16; p = 0.024 |

| CERAD score 4/3/2/1 (n) | 3/3/5/1 | 6/0/4/2 | 0/1/3/8 | n/a |

| Braak score I/II/III/IV/V (n) | 2/0/6/4/0 | 0/0/5/6/1 | 0/0/5/1/6 | n/a |

| Reagan score 3/2/1 (n) | 7/5/0 | 6/5/1 | 1/5/6 | n/a |

Neuropathological data were generated on coronal sections or Western immunoblots (total and PHF tau) and ELISA measurements (soluble and insoluble β-amyloid (Aß) concentration from the temporal and/or parietal cortex; diagnoses were based on clinical evaluation; brain pH was measured in cerebellum extracts. Abbreviations : A, ANOVA; Aβ, β-amyloid; AD, Alzheimer disease; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD; C, Contingency; IHC; immunohistochemistry; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NCI, no cognitive impairment; PHFtau, paired helical filament tau; SD, standard deviation; y, year. Values are expressed as mean (SD). Intergroup comparisons:

p < 0.001 vs. NCI and MCI;

p < 0.01 vs. NCI and p < 0.05 vs. MCI;

p < 0.05 versus NCI;

p < 0.01 versus NCI or MCI;

p < 0.05 versus NCI or MCI. Concentrations of Ab are expressed in pg/mg of protein or ng/ mg of tissue in soluble and insoluble fractions, respectively. Tau content is expressed in relative optical density from immunoblots. For more details on methodology see (32).

Protein Lysates Preparation

Postmortem samples, (∼100 mg), from the inferior parietal cortex from these 36 study volunteers were homogenized and centrifuged sequentially to generate a Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-soluble protein fraction that contains intracellular (cytosolic) and extracellular proteins, a detergent-soluble protein fraction containing membrane-bound and nuclear proteins and a detergent-insoluble protein fraction (formic acid extract), as described (32). Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized in 4 volumes (μl/mg tissue) of TBS buffer (50 mM tris-HCl, 138 mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl containing Complete protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 0.1 mM EDTA and 1 mM each of sodium vanadate and sodium pyrophosphate as phosphatase inhibitors), then sonicated 3 × for 5 × 1 second pulse. The solution was then spin at 100,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant, the TBS-soluble fraction, was removed and kept at -80°C until needed. The pellet was homogenized in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% triton X-100 containing the same protease and phosphatase inhibitors), sonicated and spin as previously described. After removing the supernatant (detergent-soluble protein fraction), the pellet was homogenized in 4 volumes (μl/mg pellet) formic acid, sonicated for 10 × 1 second pulse and spin at 10000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant (detergent-insoluble protein fraction) was removed, separated in aliquots, protein concentration was measured and the proteins were dried using a SpeedVac (Thermo Savant, Waltham, MA). For ELISA analysis the proteins were solubilized in guanidine 5M. The proteins for Western immunoblotting were solubilized in Laemmli's loading buffer (60 mM Tris, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.0025% bromophenol blue, 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.5), and kept at -80°C until needed. Protein concentration for all fractions was determined using bicinchonic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Western Immunoblotting and ELISA

TDP-43 and tau were quantified in the TBS-soluble, detergent-soluble and detergent-insoluble fractions of brain homogenates using Western immunoblot. Proteins (15μg/sample) were heated at 95°C for 5 minutes in Laemmli's loading buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE on an 8% polyacryamide gel, transferred on a PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Billerica, MA) and blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% tween 20 in PBS buffer (Bioshop Canada Inc, Burlington, ON, Canada), as previously described (32). Proteins were detected using appropriate primary antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody and chemiluminescence reagents (Lumiglo Reserve, KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Band intensities were quantified using a KODAK Imaging Station 4000 MM Digital Imaging System (Molecular Imaging Software version 4.0.5f7, Carestream Health, Rochester, NY).

β-amyloid 40 (Aß40) and 42 (Aß42) concentrations were measured using specific Human Aß ELISA kits from Wako (Osaka, Japan), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The plates were read at 450 nm using a Synergy HT multi-detection microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT).

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence labeling was performed on 6-μm-thick sections of paraffin-embedded parietal cortex samples from the Religious Orders Study. Prior to immunostainning, the sections were microwaved 2 × for 2 minutes each in 0.01M citrate buffer, pH 6.0 for antigen retrieval. Anti-N-TDP-43 and anti-TDP-43 pS409/S410 were used as primary antibodies and processed as previously described (47). The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Pierce) for differentiation of cytoplasmic or nuclear TDP-43 staining. An analysis of each section was performed to determine the presence of extranuclear TDP-43 staining. Scores between 0 and 3 (0 = none, 1 = rare or mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) were assigned to each section for the presence of cytoplasmic TDP43 staining with the phosphorylation-dependent and independent antibody. Assessment was performed by an observer (C.T.) who was blind to clinical and neuropathological diagnoses. Sections with abundant intracellular sources of autofluorescence, such as lipofuscin pigments, were frequently found and were excluded.

Data Analysis

Statistical comparisons of data between groups were performed depending on the normality of distribution and variances equivalence between groups. In cases of equal variance and normal distribution, we used ANOVA followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons (e.g. Tukey-Kramer) when appropriate. When homogeneity of variance was not confirmed (p > 0.05 using Bartlett's test), Welch ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc tests were computed. Variances were reduced using logarithmic transformations to provide more normally distributed measures when needed. Otherwise, Kruskal-Wallis independent group comparisons were performed followed by Dunn's multiple comparison tests. For comparaisons between 2 groups, Mann-Whitney test was performed. Finally, coefficient of determination (r2) and significance of the degree of linear relationship between various parameters were determined with a simple regression model. All statistical analyses were done using JMP Statistical Analysis Software (version 8.0.2)

Results

Clinical and neuropathological data of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. As expected, individuals with AD showed significant cognitive deficits as assessed with mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and global cognition measures based on 19 cognitive performance tests vs. persons with MCI and NCI. The accumulation of tau, PHFtau and Aβ42 in the cerebral cortex was more prominent in AD, despite important inter-individual variation (Table 1).

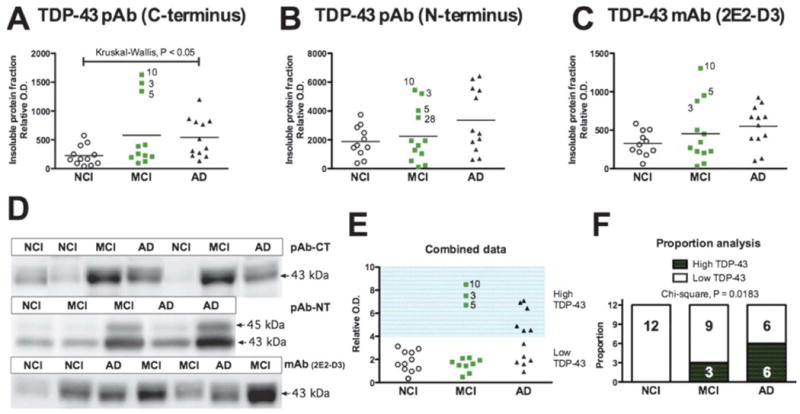

Proteinopathy has been associated with the conversion of pathogenic protein/peptide to insoluble aggregates. Hence, we first focused on the quantification of TDP-43 in the detergent-insoluble fraction in which TDP-43 aggregates are expected. Using 3 different antibodies, we determined that concentrations of detergent-insoluble TDP-43 were higher in an important subset of persons with MCI or diagnosed with AD (Fig. 1). Although a non-parametric distribution-free analysis with a Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed the increase in detergent-insoluble TDP-43 in the AD group (p < 0.05; Fig. 1A), the concentration of insoluble TDP-43 displayed a bimodal distribution, rendering statistical comparison hazardous. Indeed, only a few MCI or AD cases had increased levels while most remained comparable to controls (Fig. 1A-E). For example, subjects 3, 5 and 10 from the MCI group were consistently elevated (Fig. 1A-E). To assess these differences between groups better, we compared the proportion of individuals with a high level (as defined as a relative O.D. over 4) of TDP-43 using a contingency table with data combined from all experiments (Fig. 1E). The data from the 3 experiments were combined by expressing individual data to their respective controls. We found that the proportion of samples with a high level of TDP-43 was significantly increased in AD (Fig. 1F). Indeed, 3/12 (25%) and 6/12 (50%) of individuals with a clinical diagnosis of MCI and AD, respectively, had high concentrations of detergent-insoluble TDP-43, whereas this was not the case in any of the controls (Fig. 1E, F). In addition, correlative analyses showed that detergent-insoluble TDP-43 was associated with an antemortem level of perceptual speed, a measure of executive function (Table 2), with increased Aβ and tau pathologies (Table 3), but not with the neuropathological diagnosis of AD (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A261). However, among all the neuropathological (plaques and tangles, Braak/CERAD/Reagan scales), genetic (ApoE), biochemical (Aβ and tau) and cognitive variables (evaluation of cognitive domains and MMSE) available, none clearly distinguished the 3 MCI individuals with high TDP-43 pathology from the other 9 subjects.

Figure 1.

Accumulation of total TDP-43 in detergent-insoluble fractions from the parietal cortex of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer disease (AD). (A-C) TDP-43 was measured by Western imunoblotting in the detergent-insoluble fraction (formic acid extracts) using a C-terminal polyclonal antibody (pAb-CT) (A), an N-terminal polyclonal antibody (pAB-NT) (B), and a total TDP-43 monoclonal antibody (mAb [2E2-D3]) (C). Statistical comparisons in panels A-C were performed using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Each point represents an individual and the horizontal bar is the average (n = 11-12 per group). (D) Examples of immunoblots. (E, F) The proportion of subjects with high levels of TDP-43 deposition in the formic acid extracts was higher in AD patients (E) as determined with a contingency analysis followed by a Pearson's chi-square test (F).

Table 2. Correlations Between Antemortem Cognitive Performance and Cortical Concentrations Of TDP-43 in Tris-Buffered Saline-, Detergent- and Formic Acid-Soluble Fractions.

| Total TDP43 | IF | Phosphorylated TDP43 | IF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractions: | formic acid 43 kD |

qualitative assessment | TBS 35 kD |

detergent 43 kD |

formic acid 25 kD |

qualitative assessment | |

| Size: | |||||||

| Cognitive domain | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | |

| Episodic memory | ∼0 | -0.10* | +0.18** | +0.18** | -0.04 | -0.18* | |

| Semantic memory | ∼0 | -0.04 | +0.04 | +0.06 | ∼0 | 0.14* | |

| Working memory | ∼0 | ∼1 | +0.08 | +0.10* | ∼0 | -0.16* | |

| Perceptual speed | -0.11* | -0.24** | ∼0 | +0.04 | -0.07 | -0.35*** | |

| Visuospatial ability | -0.02 | ∼0 | +0.14* | ∼0 | ∼0 | -0.23** | |

| Global cognitive score | -0.06 | -0.11* | +0.15* | +0.15* | ∼0 | -0.27** | |

Antemortem composite indexes of global cognition were determined as described (53). Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease patients; IF, immunofluorescence; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NCI, no cognitive impairment; TBS, tris-buffered saline; Statistical analyses were performed using linear regression including all subjects (NCI, MCI and AD): (−), negative correlation; (+), positive correlation;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Table 3. Summary of Correlative Analysis between TDP-43 Concentrations and Markers of Amyloid and Tau Pathologies in the Cortex of All Patients.

| Total TDP43 | Phosphorylated TDP43 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractions: | TBS 43 kD |

35 kD | detergent 43 kD |

formic acid 43 kD |

TBS 43 kD |

35 kD | detergent 43 kD |

formic acid 25 kD |

|

| Size: | |||||||||

| Markers | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | r2 | |

| Amyloid-related: | |||||||||

| Soluble Aβ42 | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | -0.18** | -0.11* | ∼0 | |

| Insoluble Aβ42 | ∼0 | 0.03 | ∼0 | +0.10* | ∼0 | -0.06 | -0.04 | +0.09* | |

| Amyloid plaques counts | -0.03 | ∼0 | ∼0 | +0.14* | ∼0 | ∼0 | -0.03 | ∼0 | |

| Diffuse plaque counts | ∼0 | ∼0 | -0.09* | +0.04 | ∼0 | -0.11* | -0.16** | +0.09* | |

| tau-related: | |||||||||

| Insoluble tau (total) | -0.03 | -0.04 | ∼0 | +0.18** | ∼0 | -0.04 | -0.07 | +0.05 | |

| PHFtau | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | +0.23** | ∼0 | ∼0 | -0.08* | ∼0 | |

| Neurofibrillary tangles | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | +0.07 | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | |

| TDP-43 IF qualitative assessment | |||||||||

| TDP-43 | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | +0.10* | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | |

| pTDP-43 | -0.13* | -0.08 | ∼0 | +0.38*** | ∼0 | ∼0 | ∼0 | +0.17* | |

Neuropathological data were generated on coronal sections or Western immunoblots (Insoluble and PHF tau) and ELISA measurements (soluble and insoluble Aß42) from the parietal cortex.. Abbreviations: Aβ, β-amyloid peptide; AD, Alzheimer disease; detergent, proteins soluble in detergent buffer; formic acid, proteins insoluble in detergent buffer; IF, immunohistofluorescence; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NCI, no cognitive impairment; PHFtau, paired helical filament tau; TBS, protein soluble in tris-buffered saline ; Statistical analyses were performed using linear regression including all subjects (NCI, MCI and AD): (−), negative correlation; (+), positive correlation;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

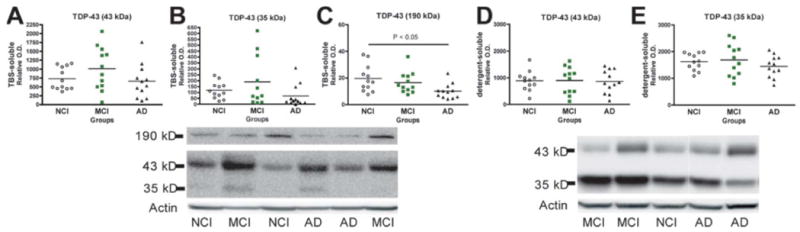

We next wanted to determine whether the above changes were associated with alterations of TDP-43 in the fractions containing TBS-soluble cytosol and extracellular proteins and the fractions with detergent-soluble membrane and nuclear proteins. No significant differences in TDP-43 and its 35-kDa fragment were detected in either TBS and detergent-soluble fractions (Fig. 2). We nevertheless observed a weaker TDP-43-positive 190-kDa band, which could represent an oligomeric form of TDP-43. Alternatively, it could be an SDS-resistant TDP-43/protein- and/or RNA-complex associated with normal physiological function of TDP-43. Interestingly, this higher molecular weight TDP-43-positive band was decreased in AD (-48% versus NCI, p = 0.019, Kruskal-Wallis test).

Figure 2.

Unchanged concentrations of total TDP-43 in soluble fractions from the parietal cortex of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer disease (AD). (A-E) TDP-43 was measured by Western immunoblotting in the TBS-soluble (cytosol) (A-C) and detergent-soluble (membrane/nucleus) fractions (D-E) using a C-terminal polyclonal antibody or a monoclonal antibody (2E2-D3). Each point represents an individual and the horizontal bar is the average (n = 11-12 per group). Statistical comparisons between groups were performed with Kruskal-Wallis tests.

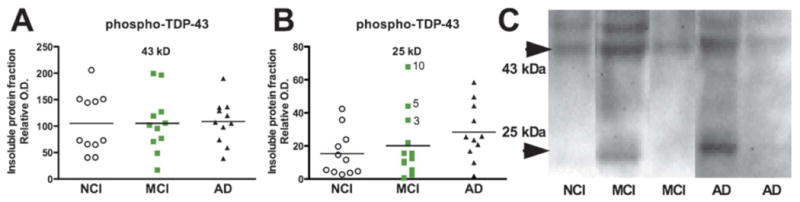

The pathogenicity of TDP-43 has been associated with its phosphorylation. Much interest is devoted to the 25-kDa C-terminal fragment of TDP-43, which is more prone to phosphorylation at S409/S410, and is particularly neurotoxic in vitro (17, 48). Hence, we investigated the concentration of phospho-TDP-43 in our samples. In the formic acid extracts containing detergent-insoluble proteins the signal was relatively weak, perhaps due to a partial loss of phospho-epitopes during the tissue preparation steps. However, both the 43- and 25-kDa bands were detected and quantified, revealing no major differences between groups (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the 25-kDa phosphorylated C-terminal fragment of TDP-43 showed a trend toward an increase in AD and was relatively high in the same 3 patients with MCI (subjects 3, 5 and 10) (Fig. 3B). The 25-kDa fragment was also positively associated with accumulation of detergent-insoluble Aβ42 (r2 = +0.09, p < 0.05, Table 3).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of phosphorylated TDP-43 in insoluble fractions from the parietal cortex of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer disease (AD). (A-C) TDP-43 was measured by Western immunoblotting in the detergent-insoluble fraction (formic acid extracts) using a polyclonal antibody targeting TDP-43 phosphorylated at serine 409/410. The signal was relatively weak and bands at 43 and 25 kDa were quantified. Each point represents an individual and the horizontal bar is the average (n = 11-12 per group). No statistical difference was detected using Kruskal-Wallis tests.

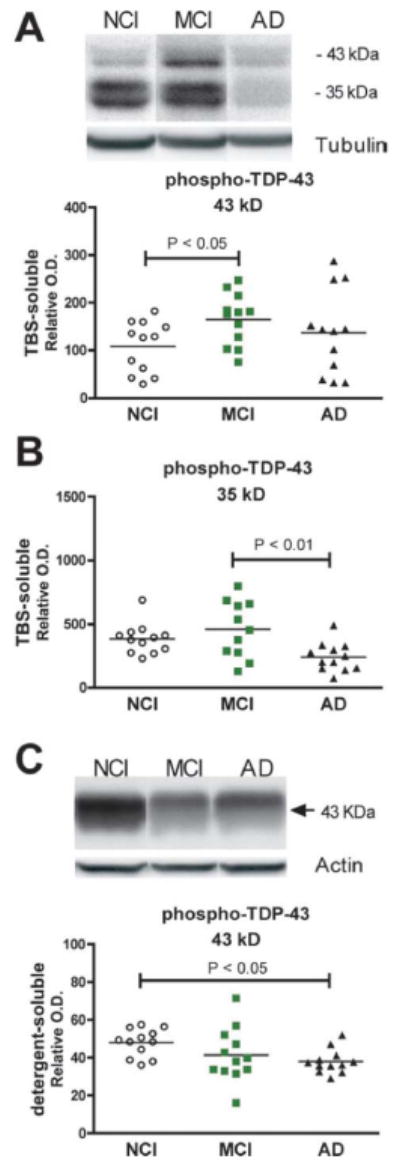

Soluble protein fractions were also subjected to immunoblot for phospho-TDP-43 and several significant alterations were detected. First, the TBS-soluble phospho-TDP-43 was increased in MCI vs. NCI (+ 35%, p = 0.0304, Mann-Withney), but showed an abnormal distribution in the AD group (Fig. 4A). Second, the 35-kDa phospho-TDP-43 fragment remained high in the cortex of persons with MCI but was decreased in AD (-47% compared to MCI, p < 0.01, Welch-ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test; Fig. 4B). Finally, we observed a significant decrease of phospho-TDP-43 in the detergent-soluble fraction (-21% compared to NCI, p < 0.05, Welch-ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test; Fig. 4C). Detergent-soluble phospho-TDP-43 was decreased in individuals with a neuropathological diagnosis consistent with a high likelihood AD (Braak IV-V and Reagan) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A261) (44).

Figure 4.

Alteration of phosphorylated TDP-43 in soluble fractions from the parietal cortex of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer disease (AD). (A-C) TDP-43 was measured by Western immunoblotting in the TBS-soluble (cytosol) (A, B) and detergent-soluble (membrane/nucleus) fractions (C), using a polyclonal antibody, targeting TDP-43 phosphorylated at serine 403/404. Each point represents an individual; the horizontal bar is the average (n = 11-12 per group). Statistical comparisons were performed using a Mann-Whitney U test (A) or Welch-ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test (B, C). NC = no cognitive impairment.

Next, we performed correlative analysis between soluble phosphorylated species and both levels of cognition and neuropathology. We first found a significant relationship between the TBS-soluble 35-KDa fragment and detergent-soluble full-length TDP-43 with cognitive performance before death, particularly strong with episodic memory (r2 = +0.18, p < 0.01, Table 2). In addition, the TBS-soluble phospho-TDP-43 35-KDa fragment was inversely correlated with soluble Aβ42 whereas concentration of detergent-soluble phospho-TDP-43 was inversely associated with soluble Aβ42, amyloid plaques, PHFtau levels and tangles counts (Table 3).

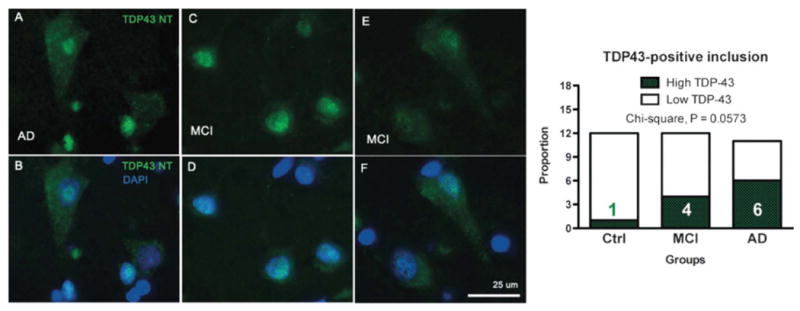

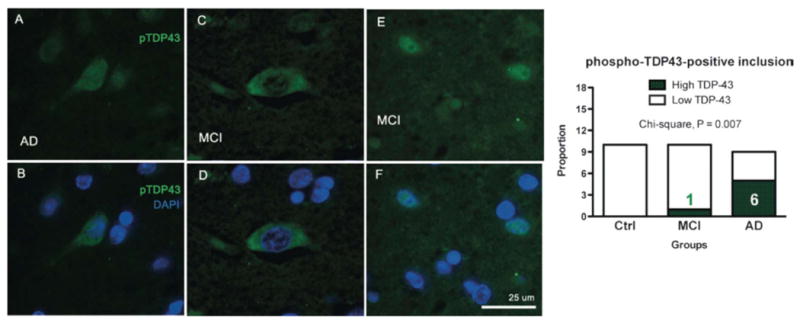

To evaluate the subcellular distribution of TDP-43, we performed immunofluorescence staining using antibodies targeting TDP-43 (Fig. 5) and phospho-TDP-43 (Fig. 6) on paraffin-embeded sections from the parietal cortex from the same series of samples. Additional objectives included the comparison of our biochemical mesurements with a qualitative immunofluorescence approach and with the available literature. As expected, TDP-43 was normally found in the nucleus, (Figs. 5C, D, 6E, F). The frequencies of cytoplasmic TDP-43 immunolabeling were increased in MCI and AD, indicating the presence of an abnormal redistribution of TDP-43. Indeed, numerous TDP-43 inclusions were observed in 8%, 33% and 55% of persons with NCI, MCI and AD, respectively (χ2 = 0.057, Fig. 5). When assessing phospho-TDP-43 the difference between groups became more definite as the frequencies of phospho-TDP-43-positive cytoplasmic inclusion were 0%, 8% and 55% in NCI, MCI and AD (χ2 = 0.007, Fig. 6). The frequency of phospho-TDP-43-positive cytoplasmic inclusion showed a significant association with the concentration of TDP-43 in the detergent-insoluble fractions (r2 = +0.38, p = 0.0002) but an inverse relationship with TBS-soluble TDP-43 (r2 = -0.13, p = 0.031), underscoring the importance of the conversion from soluble TDP-43 to aggregates (Table 3). On the other hand, TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions did not correlate with the neuropathological diagnosis of AD (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A261). Strikingly, however, our assessment of phospho-TDP-43-positive cytoplasmic inclusion showed a very strong inverse relationship with antemortem global cognitive (r2 = -0.27, p = 0.0028), especially in the sphere of perceptual speed (r2 = -0.35, p = 0.0005, Table 2). Similar, but less robust, correlations were detected with total TDP-43-positive cytoplasmic labeling (Table 2). These correlative analyses with cognitive function emphasize the importance of TDP-43 cytoplasmic distribution in the clinical expression of AD.

Figure 5.

TDP-43 immunofluorescence in the cytoplasm of neuron-like cells from the parietal cortex of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer disease (AD). (A-F) Cytoplasmic TDP-43 labeling was more frequent in neuron-like cells from individuals with MCI and AD that -in controls (Ctrl) with no cognitive impairment. TDP-43 immunostaining (using anti-N-TDP-43) is shown in green; nuclei are identified with DAPI and shown in blue. All sections were from the parietal cortex. Qualitative assessment showed a trend toward a higher frequency of subjects with high levels of TDP-43 cytoplasmic labeling in AD patients (contingency analysis followed by a Pearson's chi-square test, n = 11-12 per group).

Figure 6.

Phospho-TDP-43 immunofluorescence in the cytoplasm of neuron-like cells from the parietal cortex of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer disease (AD). (A-F) Cytoplasmic phospho-TDP-43 signal was more frequent in neuron-like cells from individuals with MCI and AD that in controls (Ctrl) with no cognitive impairment. pTDP-43 immunostaining (anti-TDP-43 pS409/S410, green); nuclei are identified with DAPI (blue). All sections are from the parietal cortex. Qualitative evaluation showed that cytoplasmic TDP-43 was more frequently observed in AD patients (contingency analysis followed by a Pearson's chi-square test, n = 11-12 per group).

Discussion

The present study revealed important biochemical and subcellular alterations of TDP-43 in an important proportion of persons with MCI or AD; the data suggest that they may contribute to the expression of cognitive impairment and could explain some inconsistencies between neuropathology and clinical impariment in individuals with MCI or AD.

Is TDP-43 Altered in MCI?

To our knowledge, TDP-43 has not been previously investigated in MCI. In general, TDP-43 changes observed here did not reach statistical significance and were at an intermediate level between NCI and AD. However, phosphorylated TDP-43 in the TBS fraction was higher in MCI compared to NCI, indicating possible compensatory mechanisms. Among individuals with MCI, 3 had consistently higher accumulation of TDP-43 in the detergent-insoluble fraction as confirmed with 3 different antibodies. This is remarkable because very few aggregating proteins have been shown to accumulate at such an early preclinical state. Our correlative analysis established an association between insoluble TDP-43 and markers of AD neuropathology. Nevertheless, even with the wealth of available clinical and neuropathological data, we could not pinpoint specific clinical or neuropathologic features of these 3 individuals that would clearly distinguish them from the rest of their group. Overall, these data suggest that there is a subset of persons with MCI with alterations in TDP-43, possibly reflecting a higher risk of developing AD, or alternatively the incipient development of another neurodegenerative disease such as FTLD-TDP.

Can TDP-43 be Considered a Neuropathological Marker of AD?

To answer that question, it is essential to put it in the general context of MCI and AD neuropathology. Amyloid and tau pathologies are the well-accepted hallmarks of AD. However, postmortem quantification has revealed that accumulations of Aβ and tau are highly variable in most individuals with MCI or AD (32, 38, 49). In addition, significant accumulation of Aβ and neuritic plaques has been described in persons with no cognitive impairment (32, 36, 50), suggesting that there are additional factors that contribute to the expression of dementia. A relative absence of postmortem tau deposition or neurofibrillary tangles has also been observed despite the antemortem clinical diagnoses of AD (32, 50, 51), showing that the clinical AD phenotype may be expressed by other pathologic processes. Thus, the interindividual variation and the lack of clear differences between groups observed here for TDP43 in both the MCI and AD groups is similar in some respects to that described for Aβ and tau. Nevertheless, it was clear in the present study that TDP-43 pathology was more commonly found in persons with MCI and AD.

Proteinopathy-associated neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by the conversion of the pathogenic protein/peptide into insoluble agregates. For example, we and others have found that insoluble stable deposits of Aβ and tau are strongly associated and particularly well correlated with antemortem cognitive impairment (32, 52-54). As for tau, Aβ and α-synuclein, TDP-43 forms insoluble deposits in the brain or spinal cord of ALS and FTDP patients (3, 4, 18, 55-58). The accumulation of detergent-insoluble TDP-43 in the parietal cortex was more frequent in individuals with MCI (25%) or AD (50%), compared to controls (NCI, 0%), based on semi-quantitative assessment using Western immunoblots. In agreement with the present results, the data accumulated so far with qualitative immunohistochemichal assessment suggest that between 14% and 57% of cases with a pathologic diagnosis of AD have evidence of TDP-43 pathology (19-30). As in ALS and FTLD-TDP, the TDP-43-positive inclusions in AD brains are mostly cytoplasmic. We also reported the presence of a 25-KDa caspase-cleaved TDP-43 fragment, in accordance with others (29, 57), consistent with the extensive amount of evidence showing caspase activation during AD progression (59-64). In cell culture systems, the caspase-processed C-terminal fragments of 35 and 25 KDa can be produced upon induction of apoptosis (65), and the aggregation prone 25-KDa C-terminal fragment results in abnormal TDP-43 cytosolic localization and increase in cellular toxicity, possibly through a toxic gain-of-function mechanism (17).

Similarly to tau, abnormal phosphorylation has been consistently associated with pathologic TDP-43 (3, 18, 56, 58). In AD, phospho-TDP-43 was detected in 14% (30), 36% and 56% (22) individuals in 3 independent series. Likewise, we identified phospho-TDP-43-positive cytoplasmic inclusions in 50% of AD (6/12) and 8% of MCI patients (1/12) using imunofluorescence measurements. In contrast, we observed a decrease of phospho-TDP-43 levels in the detergent-soluble fractions, consistent with the hypothesis that nuclear TDP-43 is translocated into insoluble deposits in AD. Hence, the present data argue for a scheme in which, during AD pathogenesis, phosphorylated TDP-43 species decrease in the cytosolic and nuclear fraction to progressively accumulate in detergent-insoluble agregates. On one hand, the diminution of phosphorylated TDP-43 in TBS and detergent-soluble fractions correlates with cognitive deterioration and accumulation of amyloid and tangle pathologies. On the other hand, severe deposition of TDP-43 was observed more frequently in MCI and AD, a phenomenon associated with both amyloid and tangle pathologies as well. Overall, alterations in TDP-43 are common but appear not to be necessary in clinical and pathologic AD. Similar to MCI, it remains unclear whether TDP43 proteinopathy in AD represents an additional neuropathologic marker of AD; or alternatively is revealing the presence of a co-existing FTLD disease.

Which TDP-43 Form Correlates Better with AD Neuropathology or Cognitive Impairment?

The present clinicopathological study allowed us to compare the value of different assessment of TDP-43. A strong correlation between the accumulation of detergent-insoluble TDP-43 and key markers of AD neuropathology, including amyloid deposition and PHFtau, was observed. Mapt (coding for tau) have been recently identified among TDP-43 RNA targets (66). It is conceivable that a loss of normal TDP-43 function could be associated to tau RNA dysregulation and increase tau pathology in AD. Nevertheless, the neuropathological diagnosis of AD did not accurately predict the amount of detergent-insoluble TDP-43 in the parietal cortex, which remained poorly associated with cognitive scores, except perhaps with perceptual speed. Alteration of phospho-TDP-43 in soluble fractions correlated better than insoluble TDP-43 with cognition, especially with episodic memory, while still showing good association with pathology, especially with soluble Aβ42. Interestingly, TDP-43-positive cytoplasmic inclusions correlated particularly well with perceptual speed, a measure of executive function, contrasting with Aβ and tau, which show the strongest association with episodic memory (32). This differential cognitive profile, which is more typical of frontal-temporal lobar degeneration rather than AD, may indicate that TDP-43 abnormalities may have a unique cognitive phenotype.

Unexpectedly, immunofluorescence assessment of cytoplamic TDP-43 correlated better with antemortem evaluation of cognitive performance. Cytoplasmic TDP-43 immunofluorescence on paraffin-embedded sections from the parietal cortex was clearly more common in AD than in NCI. Despite the fact that our immunofluorescence measurements were essentially qualititative, the presence of cytoplasmic TDP-43 was highly corelated with cognitive assessment. Such association was even stronger when using antibodies specifically targeting phosphorylated TDP-43, suggesting that immunofluorescence evaluation of TDP-43 neuropathology on brain sections is a reliable approach. Overall, our immunofluorescence measuments indicate that, despite the use of non-quantitative parameters, the presence of cytoplamic inclusions of TDP-43 determines its relationship with cognition scores and that this can only be achieved with histologic evaluation of brain sections.

Conclusion

This clinicopathological study confirmed that TDP-43 pathology occurs in an important subset of AD patients. Our observations are consistent with a pathogenic scheme in which nuclear/cytoplasmic soluble phospho-TDP43 is decreased along with an increased deposition of detergent-insoluble TDP-43, and the deposition of amyloid and tau pathology. The translocation of TDP-43 into the cytoplasm, which can be assessed by immunohistochemical analysis of brain sections, is a very good technique to assess TDP-43 neuropathology and correlates best with cognitive function. Furthermore, the presence of TDP-43 pathology in a subset of MCI patients could imply that TDP-43 impairment is an early event in the evolution of clinical AD.

In summary, our results confirm and further describe the alterations of TDP-43 in clinical and pathologic AD; they provide new data on a role for TDP-43 alterations in MCI and show that TDP-43 alterations have a complex relationship with the hallmark pathologies of AD, Aβ and tau. The exact role of TDP-43 pathology in the pathogenesis of clinical and neuropathologic AD should be the focus of further studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the hundreds of nuns, priests, and brothers from the Catholic clergy participating in the Religious Orders Study.

This work was supported by grants from the Alzheimer Society Canada (FC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (FC - MOP 102532), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (FC - 10307), and National Institute of Aging grants (D.A.B.) P30AG10161 and R01AG15819. The work of F. Calon was supported by the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

References

- 1.Johnson BS, Snead D, Lee JJ, et al. TDP-43 is intrinsically aggregation-prone and ALS-linked mutations accelerate aggregation and increase toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20329–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319:1668–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie IRA, Bigio EH, Ince PG, et al. Pathological TDP-43 distinguishes sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with SOD1 mutations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:427–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arai T, Hasegawa M, Akiyama H, et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:602–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0612-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pesiridis GS, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Mutations in TDP-43 link glycine-rich domain functions to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R156–62. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R46–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann M. Molecular neuropathology of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:232–246. doi: 10.3390/ijms10010232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Robinson J, et al. Clinical and pathological continuum of multisystem TDP-43 proteinopathies. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:180–189. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buratti E, Baralle FE. The molecular links between TDP-43 dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Adv Genet. 2009;66:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(09)66001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Kwong LK, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia and beyond: the TDP-43 diseases. J Neurol. 2009;256:1205–14. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buratti E, De Conti L, Stuani C, et al. Nuclear factor TDP-43 can affect selected microRNA levels. FEBS J. 2010;277:2268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igaz LM, Kwong LK, Chen-Plotkin A, et al. Expression of TDP-43 C-terminal Fragments in Vitro Recapitulates Pathological Features of TDP-43 Proteinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8516–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809462200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothstein JD. Current hypotheses for the underlying biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(Suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairns NJ, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. TDP-43 in familial and sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin inclusions. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:227–40. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang YJ, Xu YF, Cook C, et al. Aberrant cleavage of TDP-43 enhances aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7607–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900688106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasegawa M, Arai T, Nonaka T, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:60–70. doi: 10.1002/ana.21425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu WT, Josephs KA, Knopman DS, et al. Temporal lobar predominance of TDP-43 neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:215–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadokura A, Yamazaki T, Lemere CA, et al. Regional distribution of TDP-43 inclusions in Alzheimer disease (AD) brains: their relation to AD common pathology. Neuropathology. 2009;29:566–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uryu K, Nakashima-Yasuda H, Forman MS, et al. Concomitant TAR-DNA-binding protein 43 pathology is present in Alzheimer disease and corticobasal degeneration but not in other tauopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:555–64. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817713b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arai T, Mackenzie IRA, Hasegawa M, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:125–36. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, et al. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:435–45. doi: 10.1002/ana.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higashi S, Iseki E, Yamamoto R, et al. Concurrence of TDP-43, tau and [alpha]-synuclein pathology in brains of Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res. 2007;1184:284–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, et al. Abnormal TDP-43 immunoreactivity in AD modifies clinicopathologic and radiologic phenotype. Neurology. 2008;70:1850. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304041.09418.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rauramaa T, Pikkarainen M, Englund E, et al. TAR-DNA binding protein-43 and alterations in the hippocampus. J Neural Transm. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0574-5. Epub Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King A, Sweeney F, Bodi I, et al. Abnormal TDP-43 expression is identified in the neocortex in cases of dementia pugilistica, but is mainly confined to the limbic system when identified in high and moderate stages of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathology. 2010;30:408–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigio EH, Mishra M, Hatanpaa KJ, et al. TDP-43 pathology in primary progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia with pathologic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohn TT. Caspase-cleaved TAR DNA-binding protein-43 is a major pathological finding in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2008;1228:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lippa CF, Rosso AL, Stutzbach LD, et al. Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 burden in familial Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1483–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1447–55. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tremblay C, Pilote M, Phivilay A, et al. Biochemical characterization of Abeta and tau pathologies in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;12:377–90. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, et al. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology. 2005;64:834–41. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152982.47274.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markesbery WR. Neuropathologic Alterations in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:221–8. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imhof A, Kovari E, von Gunten A, et al. Morphological substrates of cognitive decline in nonagenarians and centenarians: a new paradigm? J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haneuse S, Larson E, Walker R, et al. Neuropathology-based risk scoring for dementia diagnosis in the elderly. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:875–85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jellinger KA. Criteria for the neuropathological diagnosis of dementing disorders: routes out of the swamp? Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:101–10. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0466-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson PT, Braak H, Markesbery WR. Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease: a complex but coherent relationship. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:1–14. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181919a48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang HX, Tanji K, Mori F, et al. Epitope mapping of 2E2-D3, a monoclonal antibody directed against human TDP-43. Neurosci Lett. 2008;434:170–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett DA. Postmortem indices linking risk factors to cognition: results from the Religious Order Study and the Memory and Aging Project. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:S63–8. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200607001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, et al. The Rush Memory and Aging Project: study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:163–75. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Boyle PA, et al. Cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:351–6. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele, AD pathology, and the clinical expression of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2003;60:246–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000042478.08543.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, et al. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychol Aging. 2002;17:179–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourasset F, Ouellet M, Tremblay C, et al. Reduction of the cerebrovascular volume in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:808–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang YJ, Gendron TF, Xu YF, et al. Phosphorylation regulates proteasomal-mediated degradation and solubility of TAR DNA binding protein-43 C-terminal fragments. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forman MS, Mufson EJ, Leurgans S, et al. Cortical biochemistry in MCI and Alzheimer disease: lack of correlation with clinical diagnosis. Neurology. 2007;68:757–63. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256373.39415.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jellinger KA, Attems J. Prevalence of dementia disorders in the oldest-old: an autopsy study. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:421–33. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson PT, Kukull WA, Frosch MP. Thinking outside the box: Alzheimer-type neuropathology that does not map directly onto current consensus recommendations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:449–54. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d8db07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Julien C, Tremblay C, Bendjelloul F, et al. Decreased drebrin mRNA expression in Alzheimer disease: correlation with tau pathology. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2292–2302. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:378–84. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naslund J, Haroutunian V, Mohs R, et al. Correlation between elevated levels of amyloid {beta}-peptide in the brain and cognitive decline. Jama. 2000;283:1571–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rutherford NJ, Zhang YJ, Baker M, et al. Novel mutations in TARDBP (TDP-43) in patients with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inukai Y, Nonaka T, Arai T, et al. Abnormal phosphorylation of Ser409/410 of TDP-43 in FTLD-U and ALS. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2899–2904. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arai T, Hasegawa M, Nonoka T, et al. Phosphorylated and cleaved TDP-43 in ALS, FTLD and other neurodegenerative disorders and in cellular models of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Neuropathology. 2010;30:170–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neumann M, Kwong LK, Lee EB, et al. Phosphorylation of S409/410 of TDP-43 is a consistent feature in all sporadic and familial forms of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:137–49. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gamblin TC, Chen F, Zambrano A, et al. Caspase cleavage of tau: linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gervais FG, Xu D, Robertson GS, et al. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid-[beta] precursor protein and amyloidogenic A [beta] peptide formation. Cell. 1999;97:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rissman RA, Poon WW, Blurton-Jones M, et al. Caspase-cleavage of tau is an early event in Alzheimer disease tangle pathology. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:121–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI20640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rohn TT, Head E, Su JH, et al. Correlation between caspase activation and neurofibrillary tangle formation in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:189–98. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang F, Sun X, Beech W, et al. Antibody to caspase-cleaved actin detects apoptosis in differentiated neuroblastoma and plaque-associated neurons and microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:379–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.LeBlanc AC. The role of apoptotic pathways in Alzheimer's disease neurodegeneration and cell death. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:389–402. doi: 10.2174/156720505774330573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dormann D, Capell A, Carlson AM, et al. Proteolytic processing of TAR DNA binding protein-43 by caspases produces C-terminal fragments with disease defining properties independent of progranulin. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1082–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sephton CF, Cenik C, Kucukural A, et al. Identification of Neuronal RNA Targets of TDP-43-containing Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1204–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.