Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the influence of race and age on aqueous humor levels of transforming growth factor-beta 2 (TGF-β2).

Methods

Patients >40 years of age and undergoing cataract or glaucoma surgery without associated significant intraocular pathology were selected for this study. In bilateral cases, only the first operated eye was included for evaluation. At the time of surgery, a small amount of aqueous was withdrawn. The concentration of total TGF-β2 was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in duplicate by a masked observer.

Results

Fifty-five aqueous humor samples were analyzed from subjects with an average age of 68.05 ± 10.94 years. Overall median TGF-β2 concentration was 247.03 pg/mL. The median concentration of TGF-β2 was higher in eyes with glaucoma than in eyes without glaucoma (269.39 vs. 165.56 pg/mL, respectively; P = 0.001). Subgroup analysis found no significant difference between African American and Caucasian American subjects in the nonglaucomatous or glaucomatous subgroups. Age showed positive correlation with TGF-β2 in nonglaucomatous eyes (r2 = 0.44, P = 0.019). No correlation between age and TGF-β2 was noted in the glaucoma group (r2 = 0.02, P = 0.343).

Conclusion

The aqueous humor concentration of TGF-β2 was significantly higher in eyes with glaucoma than in eyes without glaucoma. No significant difference between the aqueous humor levels of TGF-β2 from African American and Caucasian American subjects could be measured. However, a significant and positive correlation between age and aqueous humor concentration of TGF-β2 in the eyes of nonglaucomatous subjects was measured. These results are consistent with the idea that elevated levels of TGF-β2 within the anterior segment contribute to the development of glaucoma. In addition, the increased risk for developing glaucoma as one ages may in part be related to the rise of this cytokine.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a disease that can affect people of all ages and ethnicities. Although multiple risk factors have been identified, glaucoma is more common with increasing age and in African Americans. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in adults over 40 years of age in the United States is reported as 1.87%.1 Prospective epidemiological studies found a 4%–6% increase in risk for developing glaucoma for each year of a subject's age beyond the baseline mean age, when entered into their studies.2,3 Studies evaluating racial differences have shown that the prevalence of glaucoma in Caucasian Americans is 1.69% compared to 3.47% in African Americans.1 In addition, significant ethnic differences exist in the outcomes for many glaucoma treatments aimed at reducing intraocular pressure (IOP) and optic nerve cell damage.4 Age and race represent surrogate risk factors that parallel the underlying pathophysiological events in glaucoma.

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) has been shown to play a central role in organ development and homeostasis regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.5 In the eye, TGF-β2 is a normal component of aqueous humor and the principle isoform found in the anterior segment.6–10 Under normal conditions, TGF-β2 is thought to contribute to the development of immune privilege within the eye11; however, several studies have provided evidence that elevated levels of TGF-β2 in aqueous humor are associated with the development of primary open-angle glaucoma.8,9,12,13 The current studies were undertaken to investigate whether the increased risk in developing glaucoma in African American subjects or in aging was associated with higher levels of TGF-β2 in the aqueous humor.

Methods

This project conforms to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, and received approval from the Human Investigation Review Board at MUSC. Patients >40 years of age and undergoing cataract or glaucoma surgery without associated significant intraocular pathology (uveitis, neovascular glaucoma, etc.) were selected for the study. In bilateral cases, only 1 eye (the first operated eye) was included in the study to avoid a correlation effect in statistical analysis. Glaucoma was defined on the basis of either glaucomatous optic disc damage (neural rim thickening, notching, saucerization, etc.), or glaucomatous visual-field changes (nasal step or paracentral, Seidel or arcuate scotoma, etc.), or both. Subjects with a history of any intraocular surgery during the previous 6 months were excluded. Data on age, gender, race, and IOP (with or without medication) were collected during preoperative visit.

Aqueous humor was aspirated before any conjunctival or intraocular manipulation. At the time of surgery, a small amount of aqueous (75–100 μL) was withdrawn through an ab-externo corneal paracentesis site using a 27-gauge needle on a tuberculin syringe. All aqueous samples were stored at −80°C until analyzed. TGF-β2 was measured using the human TGF-β2 DuoSet enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay development kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), with a detection lower-limit of 31.2 pg/mL. Inactive TGF-β2 was activated, and further analysis was performed as per instructions provided by the manufacturer.

All measurements were performed in duplicate. A masked observer assessed the TGF-β2 concentration (unaware of age, race, or if the sample had been taken from a cataractous or glaucomatous eye). Results are expressed in picograms per milliliter. Descriptive statistics were used to report baseline parameters. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used for comparison of TGF-β2 values by race, as the data were not normally distributed. Due to the limited number of cases, it was not possible to do multivariate analysis. The level of significance was set at ≤0.05 (two-sided) in all statistical tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, ver. 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Fifty-five aqueous humor samples were analyzed from subjects with an average age of 68.05 ± 10.94 years. Of these 55 subjects, 32 (58.2%) were women, 38 (69.1%) were Africa American, and 43 (78.2%) were found to have glaucoma. Age in the nonglaucomatous and glaucomatous groups was not significantly different (median age, 65 vs. 68 years, respectively; P = 0.569). Overall demographics of the subgroups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and Transforming Growth Factor-Beta 2 Results of the Study Populations

| Study groups and comparisons | Nonglaucomatous eyes | Glaucomatous eyes |

|---|---|---|

| African American (sample size) | N = 5 | N = 33 |

| Median age (range, year) | 63 (52–88) | 66 (42–88) |

| Gender (no. of men and women) | M = 0; W = 5 | M = 15; W = 18 |

| Median IOP (range, mmHg) | 16 (12–20) | 18 (11–29) |

| Median TGF-β2 (range, pg/mL) | 165.69 (54.84–616.31) | 269.39 (59.56–577.38) |

| Caucasian American (sample size) | N = 7 | N = 10 |

| Median age (range, year) | 73 (51–80) | 74 (58–86) |

| Gender (no. of men and women) | M = 2; W = 5 | M = 6; W = 4 |

| Median IOP (range, mmHg) | 14 (11–17) | 17 (11–30) |

| Median TGF-β2 (range, pg/mL) | 145.54 (43.70–229.87) | 266.58 (195.22–430.16) |

TGFβ2, transforming growth factor-beta 2; IOP, intraocular pressure.

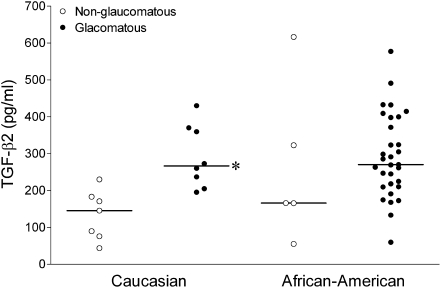

For all samples, median aqueous humor TGF-β2 concentration was 247.03 pg/mL (range 43.7–616.3). In nonglaucomatous eyes, median aqueous humor TGF-β2 concentration was 165.56 versus 269.4 pg/mL for glaucomatous eyes (P = 0.001, Mann–Whitney test). Analysis of racial subgroups found that median TGF-β2 concentration in nonglaucomatous Caucasian American subjects (145.5 pg/mL) was significantly lower than that in glaucomatous Caucasian American subjects (266.6 pg/mL; P = 0.002). However, no significant difference between median nonglaucomatous and glaucomatous African American subjects could be detected (P = 0.353; Fig. 1). Analysis of African American subjects versus Caucasian American subjects found no significant difference when comparing either the nonglaucomatous (P = 0.372) or the glaucomatous groups (P = 0.977).

FIG. 1.

Aqueous humor concentrations of TGF-β2 in nonglaucomatous and glaucomatous African American and Caucasian American subjects. Values are for individual subjects; the horizontal line represents the median value for each group. Groups were compared using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test. The asterisk represents a significant difference (P < 0.05) between nonglaucomatous and glaucomatous subjects within a racial group. No significant difference was measured when corresponding African American and Caucasian American groups were compared. TGF-β2, transforming growth factor-beta 2.

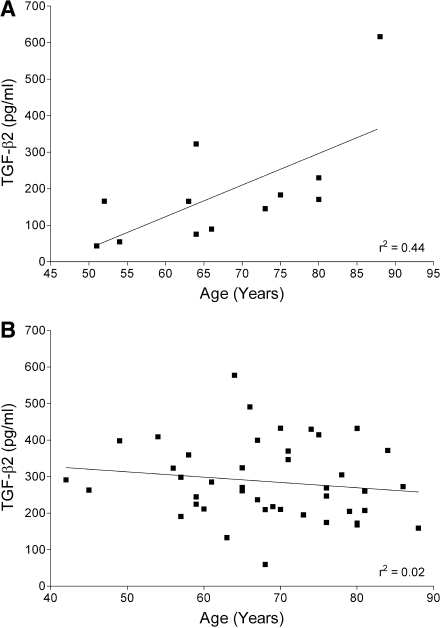

As no significant difference was detected between racial subgroups, these racial data were combined for analysis of age-dependent changes in aqueous humor concentration of TGF-β2. Figure 2 illustrates the age-dependent changes in TGF-β2 in aqueous humor samples from nonglaucomatous and glaucomatous eyes. In nonglaucomatous eyes, a significant correlation was found between increasing TGF-β2 concentrations and advancing age (r2 = 0.44, P = 0.019). However, no correlation between TGF-β2 and age was measured in samples from glaucomatous eyes (r2 = 0.02, P = 0.343).

FIG. 2.

Scatter-plots illustrating the age-dependent changes in TGF-β2 in aqueous humor samples from nonglaucomatous (A) and glaucomatous eyes (B). The solid line represents the linear regression analysis in each group.

Discussion

TGF-β is a family of proteins consisting of three isoforms: TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3. Responses to the three isoforms are mediated by binding to a receptor complex composed of type I and II receptors, which activate both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling cascades. In the eye, TGF-β2 is a normal component of aqueous humor and the principle isoform found in the anterior segment.6–10 Under normal conditions TGF-β2 is thought to contribute to the development of immune privilege within the eye.11 However, elevated levels of TGF-β2 have been associated with the development of open-angle glaucoma.9,10,12 TGF-β2 is thought to contribute to the development of glaucoma by increasing the secretion of extracellular matrix materials, increasing extracellular matrix crosslinking, and reducing protease activity and the formation of cellular stress fibers in the trabecular meshwork.14 These events are thought to increase the resistance of aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular meshwork, thereby elevating IOP.

In the current study, we found that significantly higher levels of aqueous humor TGF-β2 in eyes diagnosed with glaucoma when compared to samples from nonglaucomatous eyes. Our results are consistent with previous studies showing that TGF-β2 levels are higher in individuals with a glaucoma diagnosis.9,10,12 These results, together with studies showing that TGF-β2 increases outflow resistance and IOP in ex vivo and in vivo glaucoma models,15,16 support the idea that elevated levels of TGF-β2 contribute to the development of open-angle glaucoma.

Analysis of racial subgroups revealed that aqueous humor concentrations of TGF-β2 were not significantly different in African American subjects compared to Caucasian American subjects, in the glaucomatous or nonglaucomatous eyes. The close agreement of TGF-β2 levels in the glaucomatous group of African American and Caucasian American subjects provides evidence that the increased rate of glaucoma progression observed in studies of African American subjects cannot be attributed to the difference in TGF-β2 levels in the anterior segment. However, in the nonglaucomatous group, aqueous humor concentrations of TGF-β2 show a trend toward higher aqueous humor levels of TGF-β2 in the African American subjects (165.69 pg/mL) compared to the Caucasian American subjects (145.54 pg/mL). This trend may provide a partial explanation for the higher incidence of glaucoma in African Americans than in Caucasian American subjects. Additional studies with larger sample sizes will be required to determine whether the risk of developing open-angle glaucoma associated with racial differences is in part related to higher levels of TGF-β2.

In glaucomatous subjects, age did not show any correlation with the aqueous humor concentration of TGF-β2. However, in nonglaucomatous subjects, age was positively correlated (r2 = 0.44) with the aqueous humor concentration of TGF-β2. Higher aqueous humor levels of TGF-β2 with increasing age may help to explain why the incidence of glaucoma increases with age. TGF-β2 aqueous humor levels increase with increasing age, and this is consistent with tonographic studies showing that outflow facility decreases with age in nonglaucomatous individuals.17 In contrast to our results, Yamamoto and colleagues reported that the TGF-β2 concentration in aqueous humor from the anterior chamber decreases with age.13 The difference in results is not readily apparent; however, the sensitivity of detection methods may have played a role. Finally, although the original data by Tripathi and colleagues did not explicitly examine the relationship between age and TGF-β2, our examination of their results indicates a moderately positive correlation between age and TGF-β2 in nonglaucomatous subjects.9 Taken together, these reports support the idea that the elevation of TGF-β2 within the anterior segment provides a partial explanation for the increasing risk of developing glaucoma in an aging population.

In summary, our results confirm that the aqueous humor concentration of TGF-β2 in glaucomatous subjects is significantly higher than that in nonglaucomatous subjects. We were unable to detect any significant difference in the aqueous humor levels of TGF-β2 between Caucasian Americans and African Americans. However, in the nonglaucomatous group, eyes of African American subjects demonstrated a trend toward a higher level of TGF-β2 concentration than those of Caucasian American subjects. In addition, we found that in the nonglaucomatous subjects, age was positively correlated with increasing aqueous humor concentration of TGF-β2. With continued research into cytokines such as TGF-β2 and their functions, it may be possible to understand the underlying pathophysiological basis of surrogate risk factors like age and race in the development of glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of James Fant, B.S., M.B.A., and Luanna Bartholomew, Ph.D. This study was supported in part by National Institute of Aging and an unrestricted grant to MUSC-SEI from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Friedman D.S. Wolfs R.C. O'Colmain B.J. Klein B.E. Taylor H.R. West S. Leske M.C. Mitchell P. Congdon N. Kempen J. Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2004;122:532–538. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Voogd S. Ikram M.K. Wolfs R.C. Jansonius N.M. Witteman J.C. Hofman A. de Jong P.T. Is diabetes mellitus a risk factor for open-angle glaucoma? The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1827–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leske M.C. Wu S.Y. Hennis A. Honkanen R. Nemesure B. BESs Study Group. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ederer F. Gaasterland D.A. Dally L.G. Kim J. Van-Veldhuisen P.C. Blackwell B. Prum B. Shafranov G. Allen R.C. Beck A. AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 13. Comparison of treatment outcomes within race: 10-year results. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:651–664. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang J.S. Liu C. Derynck R. New regulatory mechanisms of TGF-beta receptor function. Trends Cell. Biol. 2009;19:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jampel H.D. Roche N. Stark W.J. Roberts A.B. Transforming growth factor-beta in human aqueous humor. Curr. Eye Res. 1990;9:963–969. doi: 10.3109/02713689009069932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cousins S.W. McCabe M.M. Danielpour D. Streilein J.W. Identification of transforming growth factor-beta as an immunosuppressive factor in aqueous humor. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1991;32:2201–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tripathi R.C. Chan W.F. Li J. Tripathi B.J. Trabecular cells express the TGF-beta 2 gene and secrete the cytokine. Exp. Eye Res. 1994;58:523–528. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathi R.C. Li J. Chan W.F. Tripathi B.J. Aqueous humor in glaucomatous eyes contains an increased level of TGF-beta 2. Exp. Eye Res. 1994;59:723–727. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasquale L.R. Dorman-Pease M.E. Lutty G.A. Quigley H.A. Jampel H.D. Immunolocalization of TGF-beta 1, TGF-beta 2, and TGF-beta 3 in the anterior segment of the human eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Streilein J.W. Immunoregulatory mechanisms of the eye. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1999;18:357–370. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picht G. Welge-Luessen U. Grehn F. Lütjen-Drecoll E. Transforming growth factor beta 2 levels in the aqueous humor in different types of glaucoma and the relation to filtering bleb development. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2001;239:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s004170000252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto N. Itonaga K. Marunouchi T. Majima K. Concentration of transforming growth factor beta2 in aqueous humor. Ophthalmic Res. 2005;37:29–33. doi: 10.1159/000083019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchshofer R. Stephan D.A. Russell P. Tamm E.R. Gene expression profiling of TGFbeta2- and/or BMP7-treated trabecular meshwork cells: identification of Smad7 as a critical inhibitor of TGF-beta2 signaling. Exp. Eye Res. 2009;88:1020–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottanka J. Chan D. Eichhorn M. Lütjen-Drecoll E. Ethier C.R. Effects of TGF-beta2 in perfused human eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:153–158. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shepard A.R. Millar J.C. Pang I.H. Jacobson N. Wang W.H. Clark A.F. Adenoviral gene transfer of active human transforming growth factor-{beta}2 elevates intraocular pressure and reduces outflow facility in rodent eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:2067–2076. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaasterland D. Kupfer C. Milton R. Ross K. McCain L. MacLellan H. Studies of aqueous humour dynamics in man VI. Effect of age upon parameters of intraocular pressure in normal human eyes. Exp. Eye Res. 1978;26:651–656. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(78)90099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]