Abstract

Recent years have witnessed the growth of new information technologies and their applications to various disciplines. The goal of this paper is to demonstrate how the two innovative methods, upper level set scan (ULS) hotspot detection and the multicriterion prioritization scheme, facilitate population health and break new ground in public health surveillance. It is believed that the social environment (i.e. social conditions and social capital) is one of the determinants of human health. Using infant health data and 10 additional indicators of social environment in the 159 counties of Georgia, ULS identified 52 counties that are in double jeopardy (high infant mortality and a high rate of low infant birth weight). The multicriterion ranking scheme suggested that there was no conspicuous spatial cluster of ranking orders, which improved the traditional decision making by visual geographic cluster. Both hotspot detection and ranking methods provided an empirical basis for re-allocating limited resources and several policy implications could be drawn from these analytic results.

Keywords: Hotspot detection, multicriterion prioritization, infant mortality, social capital

INTRODUCTION

The goal of this paper is to demonstrate how to best utilize hotspot detection and multicriterion ranking methods to promote heath, both at the individual- and community-level. Improvement of hygiene, technology, and medicine has benefitted the U.S. population by increasing life expectancy and years of quality life (US DHHS 2000). However, in contrast to other industrialized countries, the U.S. has a notably low life expectancy at birth. The relatively high infant mortality rate at the national level is one of the major explanations (Paneth, 1995). According to the World Factbook (CIA 2009), the 2009 estimated infant mortality rate is 6.26 infant deaths per 1,000 live births in the U.S., which is higher than Sweden (2.75), Norway (3.58) and Canada (5.04). In response to the U.S. disadvantage, it is crucial to identify hotspots of high infant mortality and prioritize these hotspots in order to effectively and efficiently reduce infant mortality rates. In this paper, we use hotspot detection and prioritization to address two research questions related to infant health: (1) where are the hotspots of infant mortality and low birth weight, and (2) how should limited resources be applied?

Earlier studies have found that at the individual-level, low birth weight, nutrition intake, and maternal behavior are associated with infant death (McCormick 1985; Barker and Osmond 1986; Kleinman et al. 1988). At the ecological-level, air pollution (district level), income inequality (country level), and poor social conditions have been identified as being adversely related to infant health (Wilkinson 1996; 1997; Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009; Bobak and Leon 1992; Loomis et al. 1999; Waldmann 1992; Hogue and Hargraves 1993). Although the determinants of infant mortality have been discussed in the prior literature, little research has been done that combines hotspot detection and/or muticriterion ranking methods with these determinants of infant mortality in an effort to promote infant health. Therefore, in this study, we are among the first to use both hotspot detection and prioritization methods to examine the determinants of infant mortality rates and rates of low birth weight infants. This manuscript attempts to fill the gap in the literature by using a case study in Georgia. The purpose of the following discussion is to concisely articulate the linkages between infant mortality and the following factors: low birth weight, social conditions, and social capital. A more elaborate examination of these associations can be found elsewhere (Yang et al., 2009).

Low birth weight, which is when an infant weighs less than 2,500 grams at birth, is a factor that is closely associated with infant death (Paneth 1995; Barton et al., 1999). Social conditions have been regarded as fundamental causes of disease (Link and Phelan 1995; Phelan et al. 2004; Rogers et al. 2000). Neighborhood-level socioeconomic status, residents’ educational attainment, poverty, and the unemployment rate have been identified as important determinants of infant mortality. For example, mothers’ educational attainment has been identified as a crucial predictor of low birth weight. Mothers who never completed high school are almost 1.5 times more likely to have a low birth weight infant compared to those mothers with some college education (US DHHS 2000).

Social capital has been found to have an independent impact on infant mortality, after controlling for social conditions (Yang et al. 2009). It is believed that social capital is linked to infant health based on three ways. First, social capital enhances both tangible and invisible assistance, such as money, food, convalescent care, and health information (Kawachi et al. 1999; Putnam 2000). Second, social capital reinforces healthy behaviors and exerts control over deviant incidences (Berkman 1985; Kaplan et al. 1977; Kawachi et al. 1999). Third, social capital brings about advances in health through psychosocial progress (Schoenbach et al. 1986; Seeman et al. 1993). Simply put, high social capital is associated with low infant mortality. Following on this, low birth weight, social conditions, and social capital, which are all indicators of infant mortality rates, will be used in the ranking analysis.

People with more education generally have higher incomes and thus, can afford better housing and health insurance coverage. They are also more capable of adopting innovative medicines and accepting professional advice. In terms of infant mortality rates, these better social conditions could be translated into better nutrition, a cleaner and safer neighborhood, and more readily available health care services for children. Similarly, mothers suffer less pressure, receive better prenatal care, and have more thorough examinations. All of these advantages contribute to a lower infant mortality rate. Therefore, for the purpose of identifying where the limited resources should be funneled, social conditions are the most fundamental and crucial concepts. The places with the worst socioeconomic profiles deserve the most attention.

Social conditions and social capital can be defined using various indicators, such as unemployment rate, poverty status, household income, and education level. As it is difficult to determine which of these indicators is the most important, a multicriterion decision making scheme is desirable. Using this multicriterion prioritization approach, the places with lower socioeconomic profiles and weaker social capital could be regarded as places that need the most attention. The following section will provide a brief review of the hotspot detection technique, and the multicriterion prioritization scheme.

Hotspot Detection and Prioritization

To detect infant mortality hotspots in the counties of Georgia, and hence, rank those hotspots to determine where the limited resources should be allocated, two innovative statistical techniques proposed by Patil and Taillie (2004a, 2004b) are employed: upper level set (ULS) scan for arbitrarily shaped hotspots, and multiple indicator decision making schemes. Inspired by the need for geoinformatic surveillance and software for hotspot detection, the ULS scan statistic used a more flexible, but also highly sophisticated analytic and computational system to improve the disadvantages of the current popular software programs. In order to successfully conduct a surveillance system, the capability to point out potential elevated clusters is essential. Moreover, the hotspot clusters should not be constrained by circle-based spatial scan statistics. That is, the mature hotspot detection software should be able to handle arbitrarily shaped hotspot clusters; otherwise, more false alarms and a false sense of security may be introduced. The ULS scan statistic is believed to overcome these difficulties (Patil and Tallie 2004b). Therefore, this paper is going to take advantage of the ULS scan to implement arbitrarily shaped hotspot detection.

The ULS will be applied to both the infant mortality rate and the rate of low infant birth weight variables. Four groups can thus be identified: counties with only infant mortality hotspots, counties with only low birth weight hotspots, counties with both types of hotspots, which we refer to as double jeopardy, and those counties without any hotspots. An ANOVA analysis will be implemented upon these groups in order to validate the results of the ULS. The pair-wise t-test will be used to determine whether the differences between groups are statistically significant. We expect the double jeopardy counties to have the highest infant mortality and low birth weight rate. If the ANOVA and pair-wise t-test results confirm this expectation, the ULS detection results are valid.

Often times, in the social sciences, the most commonly used way to deal with multiple indicators is to create a composite index score using factor analysis or another similar variable reduction method. However, this conventional approach usually involves subjective judgments about tradeoffs among indicators. Using both Hasse diagrams of the partial order and a stochastic ordering of probability distribution with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, Patil and Taillie (2004a) suggested a multicriterion decision making scheme, which could be applied to a hotspot ranking analysis without the involvement of subjective judgment.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Units of Analysis

Counties in the state of Georgia constitute the entirety of the analytic units. Though many studies have investigated the impacts of smaller units of analysis, such as zip codes and census tracts, on health outcomes, geographic units that are smaller than the county-level come with several flaws. First and foremost, the administrative hierarchy capable of effecting policy solutions is limited to the federal, state, and county governments. This policy making structure does not extend to units below the county level. That is, the county is the smallest analytic unit with useful policy implications, and other smaller units would not be as practical as the county (Allen 2001). Second, the data at county-level are more popular and readily available. Not only does the U.S. Census Bureau prepare the data, but also they are accessible in many governmental offices. Third, census tracts or zip-code areas cannot capture dwellers’ social, economic, and living environment as completely as does the county. For these reasons, counties are considered the most appropriate units of analysis for this study. The average area of Georgia counties is 373.74 square miles and the average population density is about 188 people per square mile (Census Bureau 2008). While both area and population density vary greatly within the state, these features should not affect the prioritization and hotspot detection results.

Data Sources and Measures

There are two health outcome variables in this paper: the infant mortality rate and the rate of low birth weight infants (See Table 1 for definitions). Although the infant mortality rate is the designated dependent variable for hotspot detection, the rate of low birth weight infants is documented to be one of the best predictors of infant death. The reason for including the rate of low birth weight infants is two-fold. First, following the findings in the literature, the rate of low birth weight infants can be used to predict the infant mortality rate. If the hotspot detection results for low birth weight agree with those for infant mortality, the government could foresee the coming public health problem based on the rate of low birth weight infants. The government and policy makers may then be able to take preventive action to help mothers reduce the risk of experiencing an infant death. Second, the rate of low birth weight infants itself can also be used in ranking, and therefore will be used as one of the indicators in prioritization analysis. The Bureau of Health Professions’ Area Resource File (ARF) 2003 provides the following county-level data that enable both hotspot detection and multicriterion decision making: a three-year (1998–2000) average of the number of infant deaths, a three-year average of the number of live births, and a three-year average of the number of low birth weight infants.

Table 1.

Variables in Hotspot Detection and Prioritization

| Variables | Definition | Data Source |

Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant Mortality | Number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births | ARF | 9.34 | 3.97 |

| Low Birth Weight Rate | Number of infants weighing below 2,500 grams at birth per 1,000 live births | ARF | 90.38 | 20.50 |

| Education Attainment | Percent of population without high school diploma | Census 2000 | 29.30 | 7.54 |

| Poverty | Percent of population below poverty line | Census 2000 | 17.04 | 6.50 |

| Public Assistance | Percent of population receiving public assistance | Census 2000 | 3.78 | 1.84 |

| Not Employed | Percent of unemployed workers | Census 2000 | 5.81 | 2.26 |

| Female-headed household | Percent of female-headed households with children | Census 2000 | 8.40 | 2.74 |

| Moving | Percent of residents moving in the past 5 years | Census 2000 | 0.43 | 0.08 |

| Non-ownership | Percent of non-homeowners | Census 2000 | 0.26 | 0.08 |

| Forgery | Forgery and counterfeiting crimes per 1,000 population | UCR | 0.82 | 0.52 |

| Fraud | Fraud crimes per 1,000 population | UCR | 1.83 | 2.01 |

| Property Crime | Total part I property crimes per 1,000 population | UCR | 5.32 | 2.69 |

Socioeconomic status and other related measures of social class are associated with human health. To reflect social conditions, the following variables are included: the percentage of population aged 25 years and over without a high school diploma, the percentage of population below the poverty line, the percentage of the population receiving public assistance, the unemployment rate, and the percentage of female-headed households with children. These variables are calculated based on The 2000 Census of Population and Housing SF3 Files. Higher percentages on these measures indicate a greater disadvantage.

In addition to social conditions, there are five additional indicators derived from the concept of social capital: percent of residents moving from other counties, percent of owner-occupied households, forgery, fraud, and total part I property crime rates. The first two variables are extracted from census data and are expected to reflect neighborhood stability. This is a crucial factor in the development of social capital, because it takes time to accumulate social capital and increase residents’ interaction. Also, a recent finding suggested that home ownership is strongly related to social capital (Glaeser et al., 2002). Hence, moving and home ownership are utilized as part of the ranking indicators. The last three variables are used to reflect mutual trust and the sense of safety. Higher crime rates lead to weaker social capital within a community. To measure the degree of mutual trust and sense of safety, crime rates would be a reliable and valid indicator. High white-collar crime rates, forgery, counterfeiting, and fraud, would undermine the establishment of mutual trust. Total part I property crimes, such as burglary, larceny, arson, and auto theft, lead to the lack of a sense of neighborhood safety and thus hinder the accumulation of social capital. Based on these concepts, the five indicators must be considered in prioritization. To reduce variation, the five-year average rates calculated from the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) 1998–2002 by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) are employed. These social condition variables have been used in various health-related studies (i.e. Matthews and Yang, 2010). All of the data used in this study are available upon request.

Analytic Strategy

This paper intends to apply these two innovative information systems (ULS and prioritization) to public health issues and demonstrate how these sophisticated statistical methods promote population health. Based on the data and methods at hand, the analytic strategy is performed as follows: (1) Using ULS to detect low birth weight hotspot clusters; (2) Using ULS to identify infant mortality hotspots; (3) Comparing the results from the previous two steps and using Geographic Information Systems to identify the counties which are in “double jeopardy”; (4) Ranking the counties in double jeopardy with indicators derived from social conditions and social capital; (5) Finally, showing the ranking results and providing policy implications. The next section will demonstrate the analytic results with both figures and tables, and will be followed by the discussion section.

RESULTS

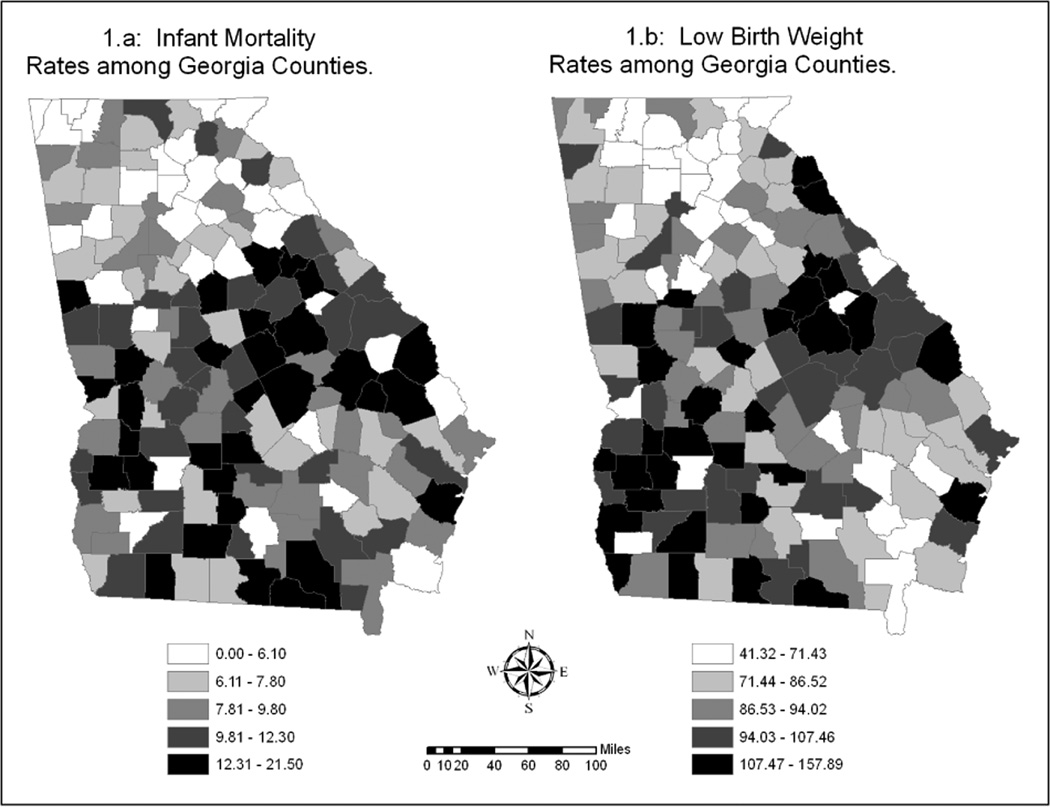

There is a total of 159 counties in the state of Georgia, and the geographical distributions of both infant mortality and low birth weight rates are shown in Figure 1.a and Figure 1.b, respectively. All counties are divided into five groups according to their mortality and low birth weight rates. It is apparent that counties in the northwestern and southeastern areas of the state are in a favorable position in contrast to those located in the middle of the state. As Figure 1.a demonstrates, most of the counties in the first quintile (lowest infant mortality rates) are concentrated in the northeast. On the other hand, those with the highest infant mortality rates are concentrated in the east-central region of the state and along the Florida border. In Figure 1.b, the southeastern counties exhibit a conspicuous cluster of low rates, and the northwestern counties continue to have better health outcomes in terms of infant birth weight. Moreover, the southwestern corner of Georgia experiences the worst low birth weight rate. Coupled with Figure 1.a, the following findings should be noted: (1) the counties in northeastern Georgia have lower infant mortality and low birth weight rates in comparison to other counties; (2) although southeastern counties have better rates of low birth weight infants, this advantage could not be translated into better infant mortality rates. In other words, despite the fact that low infant birth weight is an imperative predictor of infant death, some factors sitting between infant birth weight and death are ignored. As discussed above, social capital and other social conditions could be regarded as the missing variables (these measures will be investigated) and (3) both figures do show arbitrarily shaped clusters, which legitimizes the usage of ULS hotspot detection.

Figure 1.

The distributions of infant mortality and low birth weight rates

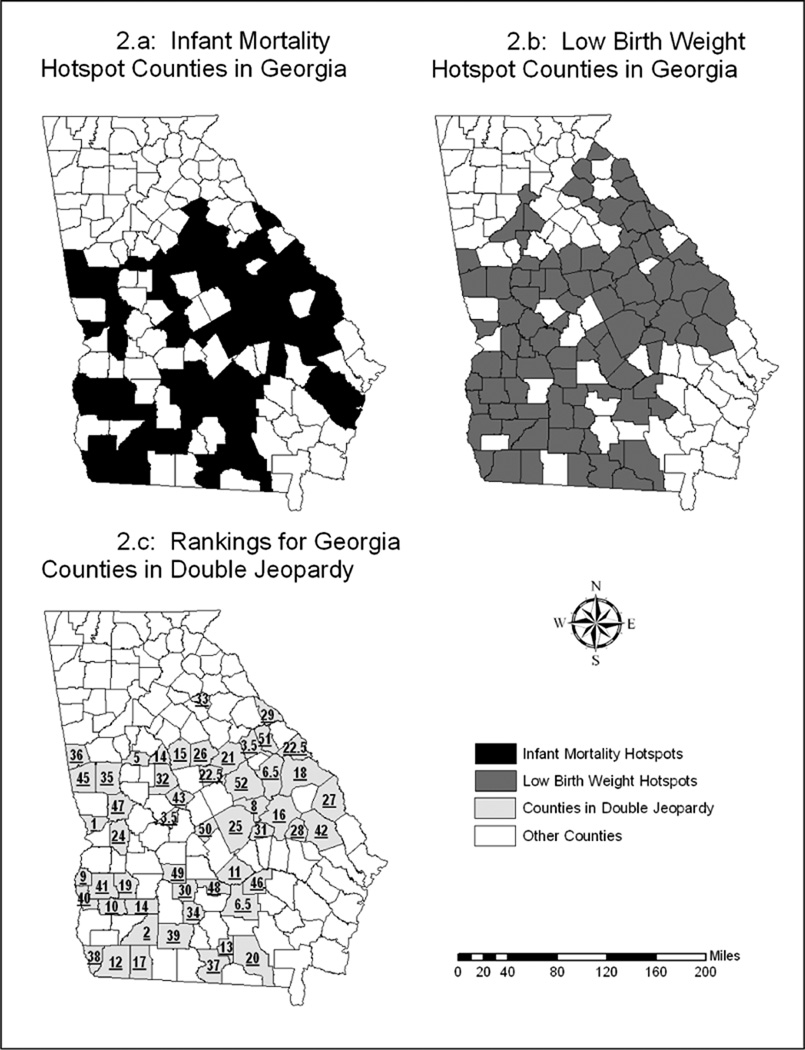

The previous paragraph introduced some initial results and accompanying maps dealing with infant mortality and low birth weight rates. However, the question of where the hotspots are located has not yet been addressed. With respect to the analytic strategies outlined above, the infant mortality hotspots should be detected first. According to the ULS results, 8 potential hotspots are initially evident, but only one hotspot comprised of 65 counties is identified with a p-value that is significant at 0.001 level. The risk ratio is 1.81, which means that the counties in this hotspot are 1.81 times more likely to have higher infant mortality rates than others. Figure 2.a shows the infant mortality hotspot counties. Compared to Figure 1.a, it’s clear that most of the counties north of the city of Atlanta are not included in the significant hotspot. Although three counties are classified into the second highest quintile group (Fannin County, White County, and Franklin County), they are not identified as part of the hotspot. The ULS hotspot detection takes the effect of neighboring counties into account, and thus, detects hotspots with greater precision.

Figure 2.

Counties in the hotspots of infant mortality, low birth weight rates, and double jeopardy

The next step in our analytic strategy is to identify hotspots of low infant birth weight rates. Nine potential hotspots are initially proposed by the ULS, and the simulation result identifies one significant hotspot consisting of 86 counties. The risk ratio is 1.35 and the p-value is 0.001. Figure 2.b demonstrates the low birth weight hotspot, which extends from the northeast to the southwestern part of the state. As illustrated in Figure 1.b, Georgia is divided by this hotspot and the northwestern and southeastern counties are more advantageous with respect to low birth weight rates. In contrast to the significant infant mortality hotspot, this low birth weight hotspot is comprised of a greater number of counties, and is concentrated in central Georgia.

Because both infant mortality and low birth weight rate hotspots are identified by the ULS, the next step is to determine which counties are classified into both, a situation we refer to as ‘double jeopardy’. In this case, there are 52 counties that meet the criteria and are identified as double jeopardy counties. Table 2 summarizes the average infant death and low birth weight rates by different groups. For all Georgia counties, fewer than 10 infant deaths occurred per 1,000 live births, while more than 90 infants per 1,000 live births were categorized as low birth weight. In Panel A, note that the highest infant mortality and low birth weight rates were both found within the double jeopardy group. Not surprisingly, those counties that are not part of any hotspot had the best infant health outcomes. Panel B indicates that the average occurrence of low birth weight and infant mortality were significantly different among groups (both p-values were below the 0.001 level). The post hoc test, Tukey’s Test, further demonstrated the comparison results (see Panel C). Specifically, the low birth weight rate of group 4 (double jeopardy) was significantly higher than that of groups 1 and 3. However, group 2 showed a rate that was not statistically different from that of group 4. With respect to infant mortality, the only insignificance was between groups 2 and 3, but, again, the double jeopardy group showed the highest infant mortality. This finding echoed our expectation and validated the ULS results. The ULS hotspot detection could precisely identify arbitrarily shaped hotspots. In addition, the hotspot detection results also confirmed earlier findings in the literature that elevated low birth weight rates could not be translated into high infant death rates directly. The average low birth weight rate was higher for the counties in the low birth weight hotspot, but their mean infant mortality rate was lower than that of the counties in the infant mortality hotspot.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, ANOVA, and Tukey’s Test results

| Panel A: Groups | Low Birth Weight Rates (LBWR) | Infant Mortality Rates (IMR) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |||

| All counties (N=159) | 90.3813 | 20.4987 | 9.3365 | 3.9745 | ||

| Group 1. Counties not in any hotspots (N=60) | 73.0467 | 12.9623 | 6.7517 | 2.1583 | ||

| Group 2. Counties only in LBWR hotspots (N=34) | 100.8191 | 13.2149 | 8.7529 | 4.4853 | ||

| Group 3. Counties only in IMR hotspots (N=13) | 78.8808 | 15.1531 | 9.7538 | 2.3761 | ||

| Group 4. Counties in double jeopardy(N=52) | 106.4331 | 14.7584 | 12.5962 | 3.1996 | ||

| Panel B: ANOVA Results | F-statistics | P-value | F-statistics | P-value | ||

| 64.4553 | 0.000 | 32.6932 | 0.0000 | |||

| Panel C: Comparisons | 1 v.s 2 | 1 v.s. 3 | 1 v.s. 4 | 2 v.s. 3 | 2 v.s. 4 | 3 v.s. 4 |

| Tukey’s Test results | ||||||

| Difference in LBWR | 27.7725*** | 5.8341 | 33.3864*** | −21.9384*** | 5.6140 | 27.5523*** |

| Difference in IMR | 2.0013* | 3.0022* | 5.8445*** | 1.0009 | 3.8432*** | 2.8423* |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

According to our analytic strategy, after identifying the 52 counties in double jeopardy, the next step was ranking these counties with a multicriterion prioritization scheme. There are 11 indicators used in the prioritization, and they are all weighted equally. Figure 2.c shows the results calculated by the cumulative rank-frequency (CRF) operator. The CRF operator is capable of linearizing a poset without combining indicators by using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling method (Patil and Taillie 2004b). It is noteworthy that the prioritization results indicated three two-way ties in ranking. Specifically, the third, sixth, and twenty-second places were shared by two counties, respectively. The results implied that given these social indicators, these counties deserved equal attention in each ranking. A smaller ranking number in Figure 2.c indicates that the county requires more immediate help with respect to low birth weight rates, social capital, and other socioeconomic profiles (detailed ranking results can be found in the appendix). For instance, the county ranked number 1 is Muscogee County. That is, based on the 11 indicators, Muscogee County needs more resources to develop better social capital and establish better social conditions, such as encouraging further interaction among neighbors, fighting vandalism, and reducing unemployment rates. Moreover, it should also be noted that the counties with larger numbers are still in need of help, while their demands are not as urgent as those of higher ranking counties. Note that lower numbers indicate higher ranks and the more immediate need for attention.

Appendix Multicriterion prioritization results for counties in double jeopardy

| Ranking | Low Birth Weight Rate |

Educational Attainment |

Poverty | Public Assistance |

Not employed |

Female- headed Household |

Moving | Non- ownership |

Forgery | Fraud | Property Crime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | 116.88 | 34.19 | 22.29 | 4.60 | 6.30 | 10.39 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 1.58 | 2.77 | 8.27 |

| 2.00 | 119.66 | 34.15 | 29.31 | 7.68 | 7.03 | 13.92 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 1.31 | 1.42 | 17.08 |

| 3.50 (tie) | 111.11 | 32.24 | 15.46 | 3.60 | 6.22 | 9.81 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 2.00 | 4.83 | 9.65 |

| 3.50 (tie) | 109.52 | 32.06 | 19.91 | 3.52 | 6.80 | 10.06 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 1.20 | 3.59 | 10.13 |

| 5.00 | 105.88 | 32.96 | 18.54 | 6.09 | 6.24 | 7.74 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 1.68 | 0.94 | 6.16 |

| 6.50 (tie) | 105.94 | 26.34 | 24.76 | 6.54 | 10.15 | 13.99 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 1.05 | 5.56 | 8.23 |

| 6.50 (tie) | 100.30 | 29.66 | 18.43 | 3.43 | 5.16 | 10.18 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 1.52 | 2.46 | 12.65 |

| 8.00 | 100.86 | 27.02 | 14.83 | 3.63 | 5.18 | 10.57 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 1.32 | 4.65 | 8.66 |

| 9.00 | 96.15 | 28.26 | 15.88 | 5.44 | 6.04 | 8.58 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 1.54 | 0.77 | 5.97 |

| 10.00 | 138.30 | 34.49 | 26.50 | 6.21 | 5.60 | 12.17 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 1.68 | 0.22 | 5.54 |

| 11.00 | 109.79 | 30.60 | 21.34 | 3.94 | 7.41 | 8.95 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 1.84 | 4.26 |

| 12.00 | 118.77 | 31.72 | 22.90 | 6.21 | 9.53 | 12.58 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.65 | 2.56 | 6.80 |

| 13.00 | 100.90 | 35.17 | 19.14 | 2.69 | 6.36 | 8.41 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 2.13 | 0.61 | 11.45 |

| 14.00 | 94.02 | 36.71 | 19.40 | 4.00 | 5.64 | 6.42 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 2.24 | 10.20 | 7.21 |

| 15.00 | 98.19 | 35.15 | 28.66 | 5.73 | 9.29 | 14.14 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 4.66 |

| 16.00 | 108.43 | 42.92 | 26.96 | 7.04 | 9.38 | 11.82 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.38 | 3.06 |

| 17.00 | 93.02 | 36.44 | 21.15 | 4.12 | 6.45 | 7.56 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 1.64 | 1.44 | 9.28 |

| 18.00 | 91.72 | 30.32 | 22.65 | 5.71 | 6.49 | 11.11 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 1.09 | 4.82 | 7.22 |

| 19.00 | 94.02 | 41.14 | 23.44 | 7.23 | 4.19 | 9.93 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 1.08 | 0.09 | 5.61 |

| 20.00 | 97.70 | 33.29 | 18.42 | 4.07 | 7.66 | 11.84 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 8.87 | 2.52 |

| 21.00 | 92.54 | 35.10 | 19.82 | 5.95 | 6.30 | 8.80 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 6.45 |

| 22.50 (tie) | 117.76 | 27.40 | 16.77 | 3.12 | 6.20 | 10.58 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 1.19 | 4.03 | 7.10 |

| 22.50 (tie) | 91.95 | 38.16 | 26.35 | 6.31 | 9.35 | 10.23 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 3.12 | 4.17 |

| 24.00 | 103.17 | 37.59 | 22.63 | 5.94 | 5.45 | 10.59 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 2.13 | 6.64 |

| 25.00 | 111.91 | 41.46 | 22.99 | 6.85 | 11.76 | 12.33 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 6.87 |

| 26.00 | 99.14 | 22.34 | 18.35 | 3.77 | 5.76 | 10.03 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 7.40 |

| 27.00 | 116.50 | 33.07 | 20.06 | 4.78 | 9.38 | 8.46 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 1.13 | 5.32 | 6.00 |

| 28.00 | 108.99 | 34.72 | 26.42 | 5.71 | 6.23 | 14.30 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 1.10 | 4.78 |

| 29.00 | 124.03 | 37.76 | 29.43 | 8.23 | 13.69 | 16.33 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 4.72 |

| 30.00 | 157.89 | 42.24 | 21.90 | 3.03 | 5.81 | 8.90 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.54 | 0.77 | 2.39 |

| 31.00 | 142.86 | 35.25 | 24.21 | 4.63 | 8.69 | 12.32 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1.11 |

| 32.00 | 92.54 | 26.62 | 20.23 | 5.43 | 12.94 | 12.09 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 2.28 | 3.29 |

| 33.00 | 108.84 | 32.12 | 23.17 | 8.34 | 7.01 | 8.59 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 9.35 |

| 34.00 | 105.96 | 32.35 | 26.73 | 6.46 | 8.01 | 11.01 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 1.22 | 1.77 | 7.05 |

| 35.00 | 93.75 | 43.06 | 26.13 | 6.41 | 7.16 | 9.57 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 1.34 | 1.15 | 5.89 |

| 36.00 | 88.35 | 24.55 | 14.57 | 3.28 | 3.84 | 5.90 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.74 | 5.71 | 4.19 |

| 37.00 | 91.23 | 30.23 | 11.47 | 3.64 | 3.85 | 7.58 | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0.64 | 2.87 | 5.30 |

| 38.00 | 98.29 | 22.03 | 19.56 | 5.20 | 9.20 | 12.35 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 8.92 |

| 39.00 | 98.59 | 35.67 | 31.28 | 5.31 | 6.82 | 14.83 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.60 | 1.43 | 3.75 |

| 40.00 | 104.76 | 34.55 | 22.42 | 3.80 | 3.64 | 9.46 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 1.15 | 2.69 |

| 41.00 | 88.49 | 18.96 | 28.27 | 2.70 | 10.23 | 7.82 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.93 | 9.92 | 9.51 |

| 42.00 | 89.42 | 22.06 | 24.49 | 2.76 | 10.23 | 7.00 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 1.01 | 1.39 | 7.41 |

| 43.00 | 131.58 | 37.59 | 27.73 | 7.37 | 7.94 | 11.28 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 4.11 |

| 44.00 | 125.85 | 34.23 | 17.83 | 5.22 | 6.96 | 9.54 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 5.59 |

| 45.00 | 102.83 | 21.08 | 15.66 | 4.34 | 7.00 | 11.39 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.78 | 10.43 | 10.93 |

| 46.00 | 115.91 | 22.79 | 19.12 | 4.73 | 7.54 | 12.12 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.26 | 8.46 |

| 47.00 | 122.91 | 35.51 | 28.55 | 10.51 | 8.49 | 13.45 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.64 | 0.04 | 5.32 |

| 48.00 | 106.25 | 38.55 | 27.39 | 5.98 | 4.40 | 11.18 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 1.16 | 9.74 | 7.39 |

| 49.00 | 87.84 | 34.02 | 13.59 | 3.90 | 5.66 | 7.36 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 2.49 | 4.09 |

| 50.00 | 107.14 | 28.98 | 15.35 | 4.25 | 5.99 | 6.34 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 1.17 | 1.25 | 3.52 |

| 51.00 | 100.00 | 30.26 | 14.18 | 2.63 | 4.69 | 7.52 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.89 | 2.87 |

| 52.00 | 96.09 | 22.28 | 9.81 | 2.38 | 3.42 | 6.75 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.52 | 2.40 | 7.57 |

Figure 2.c also shows no significant geographic connectivity of ranking orders among the 52 counties. Take the first 5 counties for example, they are not adjacent to one another at all, nor are they evenly distributed geographically (in light of a two-way tie in the third place, there were two 3.5 rankings and the fourth place county was omitted). When adding five more counties to the first five, only three counties are connected: Warren (rank order = 3.5), Jefferson (rank order = 6.5), and Johnson (rank order = 8). Were it not for the multicriterion prioritization schemes, it would be very difficult to identify where the limited resources should be allocated. In Figure 2.c, one conspicuous cluster is located in the east-central part of Georgia, which is not far from South Carolina. Although several of these counties are adjacent to one another, it does not mean that the counties in this cluster deserve more attention than others. In fact, the prioritization results suggest that several high ranking counties are located next to low ranking counties. For example, Muscogee County (rank order = 1) is adjacent to Talbot County whose rank order was 47.

This section includes the ULS hotspot detection and multicriterion ranking results. Generally, the counties in northwestern and southeastern Georgia are favorable in terms of infant mortality and low birth weight rates. Out of the 159 counties statewide, 65 counties make up the infant death rate hotspot and 86 counties comprise the low birth rate hotspot. Additionally, 52 counties are simultaneously grouped into both hotspots. The t-test results have proven that ULS hotspot detection could identify arbitrarily shaped hotspots with greater precision, which is the major advantage of the ULS detection method. Using 11 indicators, the multicriterion prioritization scheme ranks the 52 counties and indicates that there is no clear geographic clustering pattern. In other words, the traditional clustering pattern used for decision making is not as ideal as the multiple-indicator ranking scheme. The following section will discuss the policy implications derived from these results.

DISCUSSION

This goal of this paper is to apply two innovative information techniques, ULS hotspot detection and a multicriterion ranking scheme, to public health in order to demonstrate how these new methods could promote infant health. Using data from the ARF on infant death and low birth weight statistics in Georgia counties, our results show that the counties located in the central part of Georgia are at a greater disadvantage compared to those counties in the northern and southern regions. Furthermore, coupled with socioeconomic indicators from other data sources, the ranking results indicate that there is no geographic clustering pattern among the 52 counties in double jeopardy. These results concur with the literature in that although low birth weight is an important predictor of infant mortality, it cannot be directly translated into infant death, which leaves room for the participation of other ranking criteria.

Several important policy implications can be drawn from the hotspot detection and ranking results: (1) the geographic distributions of infant mortality and low birth weight rates are significant and share a similar pattern. As such, in order to more effectively improve child and maternal health, limited resources should be allocated first to central Georgia, where hotspot counties are concentrated. (2) For the areas of double jeopardy, our analysis suggests that the contextual factors, such as social capital and other maternal behaviors, are crucial for effective governance, because they could be improved via policy reform. (3) The ranking results indicate that there is no apparent spatial cluster in terms of ranking order, which provides an empirical basis for decision making and sheds new light on the concept of resource re-allocation. (4) According to the ranking order, those counties further up the hierarchy should seek to establish stronger social capital and ameliorate social conditions. Strengthening mutual trust, reciprocity, and neighbors’ interactions, combating vandalism, and maintaining residential stability are crucial to accumulating social capital. Providing affordable housing prices and lowering loan interests are two practical policies that can help to achieve this goal. Educating people with maternal and child health knowledge and disseminating related public health information could make up the deficiency of socioeconomic profiles. Decreasing unemployment rates and fighting poverty are strategies that could improve basic social conditions.

This study also bears several implications for future research in hotspot detection and prioritization. First, the state-of-the-art hotspot detection tool, specifically ULS, is only capable of univariate analysis, which is the primary reason this study employed a two-step approach to identify double jeopardy hotspots. Without a multivariate hotspot detection tool, it is difficult to statistically test whether or not the counties in double jeopardy were found by chance. A multivariate hotspot detection technique using permutations should be pursued. Second, different ranking frameworks should be applied to this data set to explore whether the prioritization results are comparable. If different approaches demonstrate similar rankings, then policy makers have strong scientific evidence to form place-specific intervention policies. Finally, the temporal dimension needs to be considered in future studies. As more and more spatiotemporal data are collected, there will be a greater demand for space-time multivariate hotspot detection and prioritization techniques.

This paper has shown how to employ innovative information techniques to facilitate population health and establish two-way communication between administration and the public. Two important components of social environment, social capital and social conditions, are integrated into this paper and several public health policy implications are derived from the analytic results. This work has addressed our two research questions by establishing and mapping counties’ rankings. Furthermore, the innovative information techniques used in this study could be suited to a wide range of applications and should not be constrained to the public health or a similar social science field; therefore, it is possible to apply these innovative information techniques to questions within a much wider range of disciplines.

Footnotes

We acknowledge the support of Penn State’s Social Science Research Institute for the continued support of Dr. Yang’s position. Additional support has been provided by the Population Research Institute (PRI) at Penn State, which receives core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24-HD41025). We thank the anonymous reviewers’ for their suggestions. We also thank Drs. G.P. Patil, Wayne Myers, and Sharadchandra Joshi for their assistance and insight.

REFERENCES

- Allen D. Social Class, Race, and Toxic Release in American Counties, 1995. Social Science Journal. 2001;38:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJP, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet. 1986;8489:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L, Hodgman JE, Pavlova Z. Cause of death in the extremely low birth weight infant. Pediatrics. 1999;103(2):446–451. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF. The relationship of social networks and social support to morbidity and mortality. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social Support and Health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, Leon DA. Air pollution and infant mortality in the Czech Republic, 1986–88. Lancet. 1992;(8826):1010–1014. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93017-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau. Population Estimate Program. 2008 Retrieved on the 30th March 2010. http://www.census.gov/popest/counties/CO-EST2008-01.html.

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) The World Factbook. 2009 Retrieved on the 30th March 2010. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

- Glaeser EL, Laibson D, Sacerdote B. The economic approach to social capital. Economic Journal. 2002;112:F437–F458. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue CJ, Hargraves MA. Class, race, and infant mortality in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(1):9–12. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BH, Cassel JC, Gore S. Social support and health. Medical Care. 1977;15(5):47–58. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197705001-00006. Supplement: Issues in Promoting Health Committee Reports of the Medical Sociology Section of the American Sociological Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R. Social capital and self-rated health: a contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman JC, Pierre MB, Jr, Madans JH, Land GH, Schramm WF. The effects of maternal smoking on fetal and infant mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;127(2):274–282. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:80–94. Spec. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis D, Castillejos M, Gold DR, McDonnell W, Borja-Aburto VH. Air pollution and infant mortality in Mexico City. Epidemiology. 1999;10(2):118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA, Yang T-C. Exploring the role of the built and social environment in moderating stress and health. Annuals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39:170–1783. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1985;312:82–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501103120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paneth NS. The problem of low birth weight. The Future of Children. 1995;5(1):19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil GP, Taillie C. Multiple Indicators, Partially Ordered Sets, and Linear Extensions: Multi-criterion Ranking and Prioritization. Environmental and Ecological Statistics. 2004a;11:199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Patil GP, Taillie C. Upper Level Set Scan Statistic for Detecting Arbitrarily Shaped Hotspots. Environmental and Ecological Statistics. 2004b;11:183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, Kawachi I, Levin B. “Fundamental Causes" of Social Inequalities in Mortality: A Test of the Theory. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45(3):265–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Nam CB. Living and Dying in the USA: Behavioral, Health, and Social Differentials of Adult Mortality. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbach VJ, Kaplan BH, Fredman L, Kleinbaum DG. Social ties and mortality in Evans County, Georgia. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;123(4):577–591. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Rodin J, Albert MA. Self-efficacy and functional ability: How beliefs relate to cognitive and physical performance. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5:455–474. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS] Healthy People 2010. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann RJ. Income distribution and infant mortality. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1992;107(4):1283–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy Societies. The Afflictions of Inequality. Routledge, London: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG. Health Inequalities: relative or absolute material standards? British Medical Journal. 1997;314:591–595. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, Pickett K. The Spirit Level: Why More equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Allen Lane (Penguin Books); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang T-C, Teng H-W, Haran M. The impacts of social capital on infant mortality in the U.S.: A spatial investigation. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy. 2009;2:211–227. [Google Scholar]