Abstract

All components of the renin angiotensin system necessary for ANG II generation and action have been reported to be present in renal proximal convoluted tubules. Given the close relationship between renal sodium handling and blood pressure regulation, we hypothesized that modulating the action of ANG II specifically in the renal proximal tubules would alter the chronic level of blood pressure. To test this, we used a proximal tubule-specific, androgen-dependent, promoter construct (KAP2) to generate mice with either overexpression of a constitutively active angiotensin type 1A receptor transgene or depletion of endogenous angiotensin type 1A receptors. Androgen administration to female transgenic mice caused a robust induction of the transgene in the kidney and increased baseline blood pressure. In the receptor-depleted mice, androgen administration to females resulted in a Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of angiotensin type 1A receptors in the proximal tubule and reduced blood pressure. In contrast to the changes observed at baseline, there was no difference in the blood pressure response to a pressor dose of ANG II in either experimental model. These data, from two separate mouse models, provide evidence that ANG II signaling via the type 1A receptor in the renal proximal tubule is a regulator of systemic blood pressure under baseline conditions.

Keywords: angiotensin II, kidney

the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is well recognized for its contributions to blood pressure regulation and sodium homeostasis, and all components of the RAS are expressed within the kidney. Within the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT), angiotensinogen (AGT) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) have been identified on the brush border of tubular epithelial cells (21). ANG II type 1A receptors (AT1AR) are localized in both apical and basolateral membranes of the PCT, with a higher density compared with the other nephron segments (20). Previous studies have also demonstrated that the ANG II concentration in the PCT is much higher than in plasma (10). These data suggest that local production and action of ANG II in the PCT may play a significant role in sodium retention and blood pressure.

The effects of ANG II on sodium transport in the PCT have been studied intensively. In the isolated PCT, ANG II stimulates sodium transport at physiological concentrations, primarily by activation of the sodium hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3) (19, 39). In vivo studies using transgenic and knockout mouse models of RAS components have also implicated PCT ANG II in blood pressure regulation. We previously generated two double-transgenic mouse models expressing human AGT (hAGT) under the control of the kidney androgen-regulated protein (KAP) promoter, which directs PCT cell-specific gene expression in an androgen-responsive manner (14, 15). In the first model, human renin expression was restricted to renal juxtaglomerular cells, its classic site of synthesis in the kidney. Juxtaglomerular-specific human renin combined with proximal tubule-specific expression of hAGT resulted in significantly elevated blood pressure, even though plasma ANG II concentrations were unchanged (13, 22). In the second model, human renin and hAGT were both coexpressed in proximal tubule cells (each under the control of the KAP promoter) resulting in elevated arterial pressure (23). These data provided strong evidence that ANG II generated in the PCT and acting in the kidney could raise blood pressure. However, because the receptors for ANG II are expressed along the entire nephron (20), it is possible that the sodium-retention and blood pressure effects evident in these animals were mediated through ANG II action at both PCT and downstream tubular segments. Recent studies by Gurley et al. (17) provide compelling data implicating an important role for PCT AT1AR in the regulation of arterial pressure.

In this study, we examined ANG II action specifically within the PCT. This was accomplished through the generation and characterization of two new transgenic mouse models. First, we developed mice expressing a ligand-independent, chronically active AT1AR mutant under transcriptional control of the PCT-specific, androgen-dependent, second generation KAP promoter (KAP2-AT1AR-N111G mice). Second, similar to the recent study by Gurley et al. (17), we developed mice with PCT-specific depletion of AT1AR (KAP2-AT1AR-KO mice), herein employing the androgen-dependent KAP2-iCre transgenic model previously reported by us (27). Subsequent characterization of these mice supports the hypothesis that AT1AR on the PCT regulate blood pressure in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of KAP2-AT1AR-N111G and KAP2-AT1AR-KO mice.

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa. To generate the KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgenic mice, a cDNA fragment encoding rat AT1AR (N111G) was inserted into the Not I site of the KAP2 construct. The KAP2 construct is composed of 1,542 bp of KAP promoter fused to a gutted coding region of the hAGT gene and has been shown to drive PCT-specific gene expression in an androgen-inducible manner (5). The rat AT1AR (N111G) cDNA fragment was amplified from the vector pRc-CMV-AT1R (provided by Dr. Walter G. Thomas, Baker Medical Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia) (1). The substitution of asparagine (N) at position 111 has been shown to confer constitutive activity on the receptor (16). All cloning junctions were confirmed by sequencing. The transgene was linearized by Spe I and Nde I digestion, gel purified, dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris·Cl pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EDTA) at a concentration of 2 ng/μl, and microinjected into the pronuclei of fertilized oocytes from C57BL/6J X SJL/J F2 mice. Among seven founder mice, line 43058/2, which exhibited the most restricted tissue-specific expression profile, was backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background for at least four generations before experimental studies. PCR was performed using genomic DNA isolated from tail clip for genotyping. Primer sequences used for genotyping and expression profiling are provided in Supplemental Table S1 (supplemental data are posted with the online version of this article).

Proximal tubule-specific AT1AR knockout mice (KAP2-AT1AR-KO) were generated by crossing AT1ARflox mice on an inbred C57BL/6 genetic background obtained from the University of Kentucky (35) with KAP2-iCre transgenic mice, which were originally generated by our laboratory (27). Both models are now available from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were studied at 4–6 mo of age. We examined both male and female mice in this study (except for Western blot analysis and radioligand binding, which were performed exclusively in female mice). However, a rise in arterial pressure in KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgenic mice was only observed in testosterone-treated female mice (see results). Therefore, for consistency, the majority of the data presented here are from females treated with testosterone. We clearly denote those experiments where males were included.

DNA and RNA isolation and PCR.

Mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. Tissues were harvested, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Tissues were cut into small pieces and digested in DNA lysis buffer (10 mM Tris·Cl pH8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, 0.4 mg/ml proteinase K) at 50°C with continuous shaking overnight. DNA was extracted with chloroform and precipitated in isopropanol. DNA (100 ng) was used for PCR. RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and incubated with DNase I (Qiagen) for 10 min at room temperature to remove genomic DNA contamination. RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using oligo(dT) primers and superscript transcriptase III (Invitrogen). For quantitative PCR, 50 ng of cDNA was PCR amplified in the presence of SYBR green using iCycler (Bio-Rad). Mouse β-actin was used as the internal control. Primers used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Constitutive activity of the AT1A receptor.

The kidney cortex from testosterone-treated female mice was separated from the medulla and was homogenized in RIPA buffer [0.05 M Tris·Cl, pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, pH8.0, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 0.5 mM PMSF, and proteinase inhibitor tablet (Roche)] on ice. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C, and supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and quantified using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Protein (10 μg) was denatured by boiling for 5 min before loading on 10% SDS-PAGE, which was then transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in 0.5% TBS-tween solution for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies overnight [pERK and ERK (Cell Signaling Technology); GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA)]. Membranes were rinsed with 5% nonfat milk three times (15 min each) and incubated with secondary antibody (sheep anti-mouse or rabbit antibody 1:1,000 dilution; GE Healthcare) and detected with ECL plus reagent (GE Healthcare). Quantification was performed with NIH Image.

Testosterone pellet implantation and ANG II infusion.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and a testosterone pellet (10 mg; Innovative Research of America) was implanted subcutaneously in the mouse back using a trocar (Innovative Research of America). Mice were infused with ANG II (800 ng·kg−1·min−1, 10 days) by using osmotic minipumps (model 1002; Alzet) implanted subcutaneously through a small incision during anesthesia with ketamine (87.5 mg/kg) and xylazine (12.5 mg/kg). All studies were performed on the animals (nontransgenic, AT1AR transgenic, or knockout) after 10 days of testosterone administration, unless otherwise indicated.

Tail cuff plethysmography and radiotelemetry.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and heart rate were measured using a computerized tail-cuff system (Visitech Systems). Mice were acclimated to the system for at least 5 days prior to measurements for 5 or 10 days. During the recording, mice were placed in restrainers on a heated platform. Care was taken to avoid overheating the mice or excessively restricting their movement. Ten preliminary cycles were performed followed by 30 measurement cycles. Values deviating more than two standard deviations from the mean were considered outliers and were eliminated from the analysis. The average of 5 or 10 days recording was used for each mouse.

Blood pressures were measured in conscious mice by using a radiotelemeter (model TA11PA-C10; Data Science International). Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (87.5 mg/kg) and xylazine (12.5 mg/kg), and the telemeter was inserted as described previously (24). After surgery, mice were kept on heating pads until fully awake. They were housed in individual cages for 10 days of recovery. SBP, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate were recorded using Dataquest ART 3.1 (Data Sciences International). Recordings were taken for 20 s every 5 min for 5 days. During the recordings, the mice were exposed to 12:12-h light-dark cycle and had access to water and food ad libitum. The measurements were averaged into 1-h and 12-h mean values. Recordings with pulse pressures < 20 mmHg or an absence of circadian rhythms were eliminated. The average of 5 days of recording was used for each mouse.

Metabolic studies and chemistry.

Mice were placed in metabolic cages (Nalgene) and had free access to chow (Teklad 7013, NIH-31 modified 6% mouse diet) and tap water. After 1 day of acclimation, food intake, fluid intake, and urine excretion were recorded for 2 days. Some mice had access to a two-bottle choice of water or normal saline. Bottle positions were switched daily to account for side bias. The mean of 2 days of measurements was used for comparisons. Urine collected from metabolic cages was centrifuged to remove food debris. Osmolality was measured with the freezing point depression method (FISKE 2400 multi-sample osmometer), and sodium and potassium concentrations were assessed by flame photometry (Instrumentation Laboratory).

Radioligand binding assays.

Angiotensin type 1 and 2 receptor density was measured using quantitative in vitro autoradiography using 125I-[Sar1, Ile8] ANG II as radioligand as described (25, 38). Briefly, 20-μm sections were cut through the midportion of the kidney by using a cryostat and mounted onto gelatin-coated glass slides. Consecutive sections from each kidney were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in phosphate-buffered NaCl containing 125I-[Sar1, Ile8] ANG II (∼90 pM) alone (total binding) or in the presence of 1 μM ANG II (nonspecific binding), 1 μM losartan (to displace binding from AT1 receptors, thus revealing AT2 receptors) or 10 μM PD123319 (to reveal AT1 receptors). The sections were then washed, dried, and exposed, along with radioactivity standards, to X-ray film (UM-MA HC medical X-ray film; Fuji). Binding densities were analyzed using a computerized imaging system and optical densities were converted (dpm/mm2; MCID Imaging). Ten samples of standard size were measured from the glomeruli and cortex in each section (n = 3–4 animals per genotype). Nonspecific binding was averaged and subtracted to give specific binding for total, AT1 and AT2 receptors. The measurements from each animal were then averaged according to genotype and expressed as means ± SE.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. For comparisons of metabolic parameters and gene expression levels between groups, Student's t-test was used. For comparisons of blood pressure and urine osmolalities, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used, followed by a Fisher least significant differences multiple-comparison correction. For real-time PCR, fold changes were calculated using the Livak method. P values < 0.05 were considered to represent statistical significance.

RESULTS

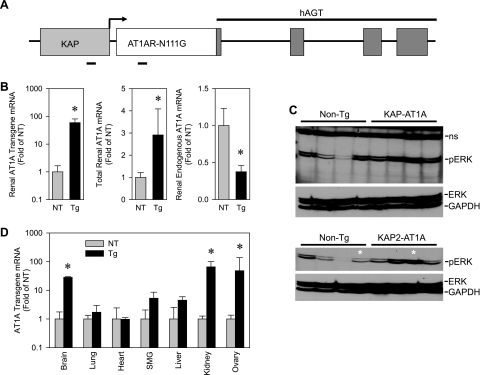

To investigate the function of the AT1ARs in the renal PCT, we overexpressed a constitutively active form (N111G) of the rat AT1AR that is active in the absence of ANG II. This form of AT1AR, when injected bilaterally into the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the brain, resulted in increased blood pressure (1). PCT specificity of the transgene was achieved using a chimeric construct containing the KAP promoter and a gutted nonfunctional portion of the hAGT gene. We have reported that this chimeric construct directs strong androgen-inducible and PCT-specific expression (Fig. 1A) (14).

Fig. 1.

Generation of transgenic (Tg) mice with proximal tubule-specific expression of constitutively active AT1AR. A: schematic of KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgene. KAP, kidney androgen-regulated protein; hAGT, human angiotensinogen. B: KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgene, total ANG II type 1A receptor (AT1AR), and endogenous mouse AT1AR gene expression in the kidney of the female KAP2-AT1AR-N111G nontransgenic (NT) and Tg mice administered testosterone. (n = 7 for each group). C: ERK phosphorylation in renal cortex from KAP2-AT1AR-N111G Tg mice after testosterone. Bottom: several samples from the top blot plus 2 additional independent samples (*). D: transgene expression in selected tissues from female NT and KAP2-AT1AR-N111G mice (Tg) after testosterone. SMG, submandibular gland. (NT, n = 4; Tg, n = 3). All data presented as means ± SE; *P < 0.05 vs. NT.

Because of androgen regulation of the transgene, we first examined expression of the transgene in kidneys of female mice in the presence and absence of testosterone. As expected, expression of the transgene in the kidney was induced strongly (∼9-fold) by exogenous testosterone (data not shown). Compared with nontransgenic mice, which by definition do not express the transgene, there was nearly a 100-fold increase in detection of transgene mRNA in kidney from testosterone-treated females (Fig. 1B). In these transgenic mice, there was a 2.8-fold increase in total (transgene and endogenous) AT1AR mRNA. Interestingly, increases in total AT1AR mRNA occurred in the face of a 2.6-fold decrease in endogenous mouse AT1AR mRNA (Fig. 1B). Consequently, there was no detectable increase in total ANG II binding in the kidney according to radioligand binding assays (Fig. 2). The radioligand was displaced by losartan, but not by PD123319, confirming that these results reflect ANG II binding to AT1, not AT2 receptors. Combined, these data suggest that the majority of endogenous wild-type receptors had been replaced with constitutively active receptors driven from the transgene. Consistent with this, under basal conditions, we observed increased signaling downstream of AT1ARs as indicated by an approximate twofold increase in phosphorylated ERK in the renal cortex of five testosterone-treated female transgenic mice compared with five testosterone-treated nontransgenic littermates when normalized either to total ERK or GAPDH (Fig. 1C). Although driven by a PCT-specific promoter, expression of the transgene was also observed in the brain and ovary (Fig. 1D). There was no detectable expression in the lung, heart, liver, or submandibular gland. Similar results were obtained in males (data not shown).

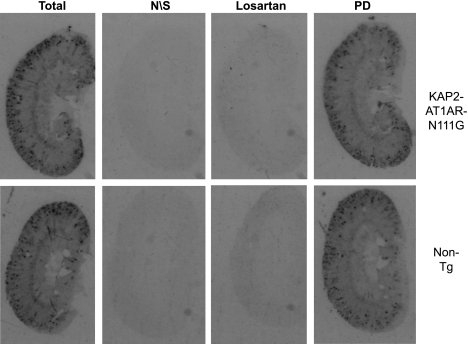

Fig. 2.

ANG II receptor expression in kidney using radioligand binding assay. ANG II binding in whole kidney from KAP2-AT1AR-N111G Tg female mice (KAP2-AT1A) administered testosterone and their NT controls. Total, binding in absence of receptor antagonists; N\S, nonspecific binding; losartan, binding after specific blockade of ANG II AT1 receptors; PD, binding after specific blockage of ANG II AT2 receptors with PD123319.

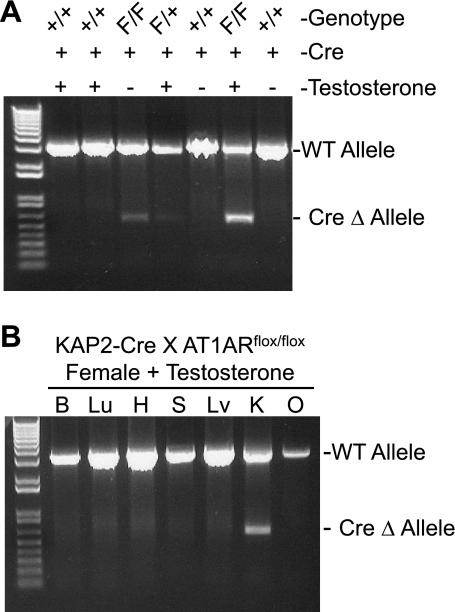

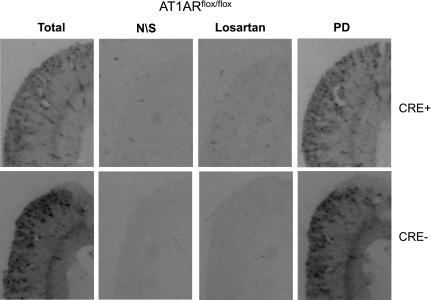

As a complement to the above model, we generated mice with PCT-specific depletion of endogenous AT1AR. This was done by breeding KAP2-Cre transgenic mice (27) for two generations with AT1ARflox/flox mice (35). Using a sensitive PCR-based assay on genomic DNA from kidney, we show that the Cre-recombination product (null or Δ allele) was detected only in kidney from mice carrying both Cre-recombinase and a floxed allele, and that the level of the null allele was increased in female mice treated with testosterone (Fig. 3A). The null allele was detected in genomic DNA from kidney, but not brain, lung, heart, submandibular gland, liver, or ovary, suggesting a high degree of tissue specificity (Fig. 3B). Overall, decreases in total AT1AR mRNA in response to Cre-recombinase averaged 30% of control mice. Despite decreases in AT1AR expression, there was no remarkable decrease in ANG II receptor binding detected in the cortex or glomeruli suggesting regulation of the AT1AR binding pool (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of proximal tubule-specific AT1AR-depleted mice. A: PCR for AT1AR genomic DNA isolated from kidney of KAP2-Cre X AT1ARflox/flox (F/F) mice, and heterozygous (F/+) and wild-type (+/+) littermates treated (+) or untreated (−) with testosterone. All mice were positive for KAP2-Cre transgene. The position of the PCR products from wild-type AT1A (WT) and recombined genomic DNA (Δ) are indicated. B: PCR for genomic DNA isolated from brain (B), heart (H), lung (Lu), spleen (S), liver (Lv), kidney (K), and ovary (O) of a KAP2-Cre X AT1ARflox/flox mouse treated with testosterone.

Fig. 4.

ANG II receptor expression in kidney using radioligand binding assay. ANG II binding in whole kidney from KAP2-Cre × AT1ARflox/flox mice and their controls. Total, binding in absence of receptor antagonists; N/S, nonspecific binding; losartan, binding after specific blockade of AT1R receptors; PD, binding after specific blockage of AT2R with PD123319.

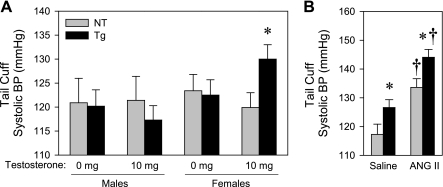

We next measured blood pressure in male and female KAP2-AT1A-N111G transgenic mice by tail cuff. There was a 10 mmHg rise in blood pressure in female transgenic mice, but not littermate controls after induction of transgene expression by testosterone (Fig. 5A). In males, although there was a marked increase in expression of the transgene after testosterone administration (data not shown), there was no difference in blood pressure in male transgenic mice, either with or without testosterone, compared with nontransgenic littermates (Fig. 5A). ANG II infusion caused a similar increase in blood pressure in both transgenic and nontransgenic controls and differences between genotypes were retained (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Blood pressure effects of AT1AR-N111G transgene expression in the proximal tubule measured by tail cuff. A: systolic blood pressure (BP) from NT and KAP2-AT1AR-N111G Tg mice, treated with 0 or 10 mg subcutaneous pellets of testosterone measured by tail cuff (male NT, n = 7; Tg, n = 9; female NT, n = 9; Tg without testosterone, n = 12; Tg with testosterone, n = 13). B: systolic BP in testosterone-administered female NT and Tg mice treated with saline (NT, n = 4; Tg, n = 9) or 800 ng·kg−1·min−1 ANG II measured by tail cuff (ANG II; NT, n = 4; Tg, n = 9). All data presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. NT, †P < 0.05 vs. saline-treated.

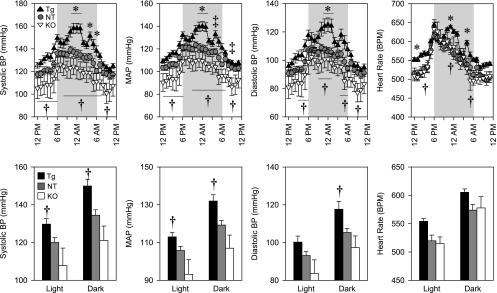

We next measured arterial pressure using radiotelemetry in testosterone-treated female KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgenic mice, KAP2-cre X AT1Aflox/flox, and their littermate controls (Fig. 6). First, we determined that there were no differences in arterial pressure or heart rate comparing control mice from the transgenic study with the control mice from the knockout study. Thus, those datasets were combined. There was a modest increase in systolic and mean arterial pressure in transgenic mice compared with controls that occurred at the peak of the blood pressure response during the dark cycle. This increase was accompanied by a transient increase in heart rate. Similarly, there were small transient decreases in mean arterial pressure in PCT-specific KAP2-Cre X AT1Aflox/flox mice compared with controls. Differences in arterial pressure were consistently observed when we compared KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgenic mice with PCT-specific KAP2-Cre X AT1Aflox/flox knockout mice suggesting a dose-dependent response to AT1AR expression. In aggregate, the differences in arterial pressure between transgenics and controls (15.4 mmHg SBP), and knockouts and controls (13.4 mmHg SBP) were slightly greater during the dark cycle than the light cycle (10.0 mmHg in transgenics and 12.2 mmHg in knockouts). Similarly, there were significant differences between transgenic and PCT-specific knockout mice during the light (21.9 mmHg systolic) and dark (28.8 mmHg systolic) phases for systolic and mean arterial pressure and during the dark phase for diastolic pressure. Similar results were obtained when a small number of testosterone-treated male control (n = 3) and knockout mice (n = 2) were added to this data set (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Fig. 6.

Arterial pressures of testosterone-treated female Tg and proximal convoluted tubule (PCT)-depleted mice measured by radiotelemetry. Top: 24-h systolic, mean and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate. Bottom: The same data shown (top) is averaged across the light and dark phases. Symbols indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05) at the indicated time interval (top) or for the indicated period (bottom) for the following comparisons: *Tg vs. NT; ‡knockout (KO) vs. Cre-control mice; †Tg vs. depleted (KO). NT, n = 11 (●); Tg, n = 6 (▲); KO, n = 6 (∇).

To assess metabolic and renal phenotypes, testosterone-treated female mice, including transgenic and nontransgenic littermate controls, were placed individually in metabolic cages and given a two-bottle choice (0.9% saline or water). There were no significant differences in body mass, food or water intake, sodium preference, total sodium intake, urinary sodium or potassium excretion, urinary volume, or urinary osmolality between groups (Table 1). Similarly, for KAP2-Cre X AT1Aflox/flox female mice treated with testosterone, no significant differences in metabolic or renal parameters were observed when mice were placed in metabolic cages with a single-choice protocol (water only) (Table 2). To address the issue of different protocols (i.e., one- vs. two-bottle), we also examined KAP2-Cre X AT1Aflox/flox mice given a two-bottle choice and observed no significant differences compared with the control group (data not shown).

Table 1.

Metabolic and hydromineral phenotypes of transgenics

| Parameter | NT, n = 5 | Transgenic, n = 10 | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass, g | 28.32 ± 0.12 | 26.63 ± 0.81 | 0.170 |

| Food intake, g/day | 3.94 ± 0.07 | 4.08 ± 0.10 | 0.356 |

| g/g/day | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.060 |

| Fluid intake, ml/day | 4.93 ± 0.36 | 4.58 ± 0.31 | 0.501 |

| ml/g/day | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.977 |

| Preference for 0.15 M NaCl, % | 49.4 ± 6.4 | 24.9 ± 7.4 | 0.053 |

| Sodium intake, meq/day | 0.91 ± 0.08 | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 0.113 |

| Urine output, g/day | 0.77 ± 0.30 | 0.65 ± 0.15 | 0.699 |

| g/g/day | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.727 |

| Urine osmolality, mosmol/kg | 5930 ± 1512 | 3909 ± 488 | 0.154 |

| mosmol/day | 2.84 ± 0.84 | 2.74 ± 0.38 | 0.901 |

| Urinary Na+, mM | 785.4 ± 180.0 | 432.0 ± 32.0 | 0.032 |

| meq/day | 0.42 ± 0.13 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.515 |

| Urinary K+, mM | 602.9 ± 160.1 | 506.8 ± 94.8 | 0.604 |

| meq/day | 0.28 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.836 |

Values are means ± SE.

Student's t-test. NT, nontransgenic.

Table 2.

Metabolic and hydromineral phenotypes of knockouts

| Parameter | NT, n = 4 | Knockout, n = 6 | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass, g | 23.54±0.24 | 22.72±0.36 | 0.127 |

| Food intake, g/day | 4.57 ± 0.10 | 4.52 ± 0.13 | 0.802 |

| g/g/day | 0.19 ± 0.00 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.434 |

| Water intake, ml/day | 3.58 ± 0.15 | 3.43 ± 0.13 | 0.501 |

| ml/g/day | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 0.899 |

| Sodium intake, meq/day | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.802 |

| Urine output, g/day | 0.55 ± 0.16 | 0.48 ± 0.12 | 0.728 |

| g/g/day | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.797 |

| Urine osmolality, mosmol/kg | 5136 ± 1094 | 5021 ± 812 | 0.679 |

| mosmol/day | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.967 |

| Urinary Na+, mM | 358.1 ± 55.3 | 370.8 ± 39.1 | 0.428 |

| meq/day | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.993 |

| Urinary K+, mM | 600.2 ± 79.6 | 695.6 ± 82.3 | 0.161 |

| meq/day | 0.31 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.10 | 0.791 |

Values are means ± SE.

Student's t-test.

Quantitative PCR was performed to examine whether constitutive activation or deletion of AT1AR in the PCT altered expression of the other RAS components in the kidney of testosterone-treated female mice (Table 3). As indicated above, we confirmed a decrease in expression of endogenous AT1AR mRNA in the transgenic mice. There were no changes in renin, AGT, ACE, ACE2, or AT1BR expression. Interestingly, a marked decrease in AT2 receptor expression was noted. In the knockout mice, a decrease in endogenous AT1AR and ACE expression was observed. A trend toward decreased AT2R mRNA was noted but did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Kidney RAS mRNA

| Gene | ΔCT | Fold of WT | ΔCT | Fold of WT | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT, n = 4 | Transgenic, n = 4 | ||||

| Renin | 3.39 ± 0.39 | 1.00(0.82−1.21) | 3.66 ± 0.16 | 0.83(0.73−0.93) | 0.553 |

| AGT | 3.85 ± 0.37 | 1.00(0.84−1.18) | 3.90 ± 0.24 | 0.97(0.84−1.12) | 0.912 |

| ACE | 1.48 ± 0.36 | 1.00(0.85−1.18) | 2.10 ± 0.19 | 0.65(0.58−0.73) | 0.177 |

| ACE2 | 5.83 ± 0.08 | 1.00(0.97−1.04) | 5.30 ± 0.56 | 1.44(1.07−1.94) | 0.319 |

| AT1A | 8.69 ± 0.54 | 1.00(0.78−1.28) | 10.78 ± 0.18 | 0.24(0.21−0.26) | 0.010 |

| AT1B | 15.85 ± 0.50 | 1.00(0.80−1.26) | 16.68 ± 0.80 | 0.56(0.34−0.93) | 0.413 |

| AT2 | 13.26 ± 0.58 | 1.00(0.77−1.31) | 15.16 ± 0.39 | 0.27(0.21−0.34) | 0.035 |

| NT, n = 5 | Knockout, n = 4 | ||||

| Renin | 5.28 ± 0.18 | 1.00(0.76−1.31) | 5.91 ± 0.42 | 0.65(0.36−1.17) | 0.181 |

| AGT | 2.79 ± 0.49 | 1.00(0.47−2.13) | 3.90 ± 0.46 | 0.46(0.25−0.88) | 0.149 |

| ACE | 1.92 ± 0.27 | 1.00(0.66−1.52) | 2.74 ± 0.10 | 0.56(0.49−0.65) | 0.036 |

| ACE2 | 4.65 ± 0.35 | 1.00(0.61−1.63) | 4.87 ± 0.23 | 0.86(0.65−1.13) | 0.648 |

| AT1A | 9.05 ± 0.38 | 1.00(0.55−1.81) | 10.75 ± 0.52 | 0.31(0.15−0.63) | 0.030 |

| AT1B | 15.46 ± 0.41 | 1.00(0.53−1.90) | 16.11 ± 0.60 | 0.64(0.28−1.47) | 0.389 |

| AT2 | 14.00 ± 0.46 | 1.00(0.49−2.04) | 15.88 ± 0.73 | 0.27(0.10−0.75) | 0.058 |

Values are means ± SE.

Student's t-test. Numbers in parentheses represent ±1 SE. Fold induction were calculated using the Livak method. CT, threshold cycle; WT, wild-type; RAS, renin-angiotensin system.

Given the importance of sodium transporters in blood pressure regulation, we measured mRNA expression of the major sodium transporters in kidney from testosterone-treated female mice to assess whether constitutive activation or loss of PCT AT1A receptors altered their expression (Table 4). There was no change in the expression of the NHE3, the three splicing forms of the sodium potassium transporter type 2 (NKCC2A, NKCC2B, NKCC2F), the sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC), the three subunits of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC-α, ENaC-β, and ENaC-γ), the sodium potassium ATPase (NaKATPase), or the sodium phosphorus transporter 2(NaPi2) in the kidney of transgenic mice. On the contrary, a significant decrease in NKCC2A, NKCC2F, and NCC expression was detected in the kidneys of knockout mice.

Table 4.

Kidney sodium transporter mRNA

| Gene | ΔCT | Fold of WT | ΔCT | Fold of WT | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT, n = 8 | Transgenic, n = 6 | ||||

| NHE3 | 3.95 ± 0.77 | 1.00(0.56−1.78) | 4.93 ± 0.72 | 0.51(0.31−0.84) | 0.388 |

| NKCC2-A | 4.45 ± 1.04 | 1.00(0.46−2.16) | 4.92 ± 0.79 | 0.72(0.42-1.25) | 0.742 |

| NKCC2-B | 5.86 ± 0.90 | 1.00(0.51−1.95) | 6.42 ± 0.63 | 0.68(0.44−1.05) | 0.642 |

| NKCC2-F | 3.23 ± 0.69 | 1.00(0.60−1.67) | 3.83 ± 0.65 | 0.66(0.42−1.03) | 0.550 |

| NCC | 1.99 ± 1.02 | 1.00(0.47−2.13) | 2.50 ± 0.93 | 0.70(0.37−1.33) | 0.726 |

| ENaC-α | 3.94 ± 0.64 | 1.00(0.62−1.60) | 4.50 ± 0.75 | 0.68(0.40−1.14) | 0.575 |

| ENaC-β | 4.95 ± 0.70 | 1.00(0.60−1.68) | 6.01 ± 0.95 | 0.48(0.25−0.93) | 0.376 |

| ENaC-γ | 4.53 ± 0.77 | 1.00(0.56−1.77) | 4.87 ± 0.65 | 0.79(0.50−1.24) | 0.752 |

| Na/K-ATPase | 0.22 ± 0.83 | 1.00(0.54−1.85) | 1.75 ± 0.82 | 0.35(0.20−0.61) | 0.225 |

| NaPi2 | −0.76 ± 0.71 | 1.00(0.59−1.69) | −0.95 ± 0.97 | 1.14(0.58−2.24) | 0.875 |

| NT, n = 5 | Knockout, n = 4 | ||||

| NHE3 | 3.50 ± 0.30 | 1.00(0.79−1.26) | 4.16 ± 0.43 | 0.64(0.45−0.90) | 0.241 |

| NKCC2-A | 3.51 ± 0.27 | 1.00(0.81−1.23) | 4.27 ± 0.06 | 0.59(0.56−0.62) | 0.044 |

| NKCC2-B | 5.08 ± 0.29 | 1.00(0.80−1.25) | 5.49 ± 0.17 | 0.75(0.66−0.86) | 0.294 |

| NKCC2-F | 1.93 ± 0.14 | 1.00(0.90−1.12) | 2.79 ± 0.24 | 0.55(0.45−0.67) | 0.015 |

| NCC | 1.13 ± 0.25 | 1.00(0.82−1.22) | 2.05 ± 0.21 | 0.53(0.45−0.62) | 0.031 |

| ENaC-α | 3.07 ± 0.17 | 1.00(0.88−1.14) | 3.77 ± 0.31 | 0.61(0.48−0.79) | 0.073 |

| ENaC-β | 4.69 ± 0.49 | 1.00(0.68−1.46) | 5.32 ± 0.43 | 0.65(0.46−0.91) | 0.379 |

| ENaC-γ | 3.03 ± 0.30 | 1.00(0.79−1.26) | 3.73 ± 0.30 | 0.62(0.49−0.78) | 0.144 |

| Na/K-ATPase | −2.34 ± 0.39 | 1.00(0.74−1.36) | −1.71 ± 0.43 | 0.64(0.46−0.91) | 0.313 |

| NaPi2 | −0.43 ± 0.27 | 1.00(0.81−1.24) | 0.13 ± 0.64 | 0.68(0.40−1.17) | 0.411 |

Values are means ± SE.

Student's t-test. Numbers in parentheses represent ±1 SE. Fold induction were calculated using the Livak method.

Finally, since expression of the KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgene was evident in the brain, we assessed whether there was altered expression of other RAS components in the brain from testosterone-treated female mice (Table 5). There was no change in renin, AGT, ACE, endogenous AT1AR, or AT1BR mRNA. However, there was a significant increase in AT2 receptor mRNA in the brains of transgenic mice. There were no significant changes in expression of any RAS gene in the brain of the PCT AT1AR-depleted mice.

Table 5.

Brain RAS mRNA

| Gene | ΔCT | Fold of WT | ΔCT | Fold of WT | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT, n = 4 | Transgenic, n = 5 | ||||

| Renin | 15.44 ± 0.86 | 1.00(0.55−1.81) | 15.10 ± 0.60 | 1.27(0.84−1.93) | 0.713 |

| AGT | 3.05 ± 0.24 | 1.00(0.85−1.18) | 3.09 ± 0.56 | 0.97(0.66−1.43) | 0.947 |

| ACE | 6.71 ± 0.16 | 1.00(0.90−1.12) | 5.89 ± 0.44 | 1.77(1.31−2.39) | 0.116 |

| ACE2 | 12.15 ± 1.01 | 1.00(0.50−2.01) | 11.30 ± 0.37 | 1.80(1.40−2.32) | 0.350 |

| AT1A | 15.37 ± 0.22 | 1.00(0.89−1.13) | 14.95 ± 0.75 | 1.34(0.80−2.25) | 0.658 |

| AT1B | 14.08 ± 0.36 | 1.00(0.78−1.28) | 13.65 ± 0.53 | 1.35(0.98−1.85) | 0.504 |

| AT2 | 12.20 ± 0.13 | 1.00(0.89−1.12) | 10.39 ± 0.35 | 3.50(2.75−4.47) | 0.006 |

| NT, n = 4 | Knockout, n = 6 | ||||

| Renin | 12.63 ± 0.93 | 1.00(0.41−2.47) | 14.56 ± 0.39 | 0.26(0.19−0.37) | 0.073 |

| AGT | 1.88 ± 0.81 | 1.00(0.53−1.90) | 2.93 ± 0.62 | 0.48(0.28−0.84) | 0.374 |

| ACE | 6.00 ± 0.43 | 1.00(0.70−1.43) | 7.14 ± 0.42 | 0.45(0.31−0.66) | 0.146 |

| ACE2 | 11.15 ± 0.82 | 1.00(0.50−2.00) | 11.04 ± 0.94 | 1.08(0.46−2.51) | 0.947 |

| AT1A | 13.10 ± 0.61 | 1.00(0.56−1.80) | 14.97 ± 0.64 | 0.27(0.15−0.48) | 0.114 |

| AT1B | 12.81 ± 0.64 | 1.00(0.54−1.87) | 13.68 ± 0.27 | 0.55(0.43−0.70) | 0.218 |

| AT2 | 10.80 ± 0.39 | 1.00(0.72−1.39) | 11.08 ± 0.47 | 0.83(0.54−1.26) | 0.727 |

Values are means ± SE.

Student's t-test. Numbers in parentheses represent ±1 SE. Fold induction were calculated using the Livak method.

DISCUSSION

Components of the RAS are present in the systemic circulation and are expressed in many different tissues and cell types; however, it has been difficult to separate the contribution of ANG II acting via its receptors in the vasculature from its actions in other cell types such as renal tubular cells. In the present study using two different mouse models, we show that PCT AT1AR play a role in the regulation of baseline blood pressure. PCT-specific overexpression of a constitutively active AT1AR mutant and cell-specific deletion of endogenous PCT AT1A receptor each had modest effects on arterial pressure compared with nontransgenic control mice. However, significant differences in arterial pressure were noted when we compared mice overexpressing constitutively active AT1AR directly with mice lacking AT1AR in the renal proximal tubule, suggesting a dose-response relationship may exist between AT1AR number in the proximal tubule and arterial pressure.

Transgenic mice expressing N111G mutant of AT1AR.

Expression of the N111G AT1AR mutant in the renal PCT resulted in a 10–15 mmHg rise in arterial pressure. However, a similar transgenic model expressing AT1AR driven by the γ-glutamyl transpeptidase promoter did not result in any elevation in arterial pressure either in normal or AT1AR-deficient mice (26). The increased arterial pressure noted in our study may be due to the constitutive activity of the AT1A-N111G receptor mutant employed herein. Interestingly, overexpression of the transgene in testosterone-treated female transgenic mice, decreased endogenous renal AT1AR by 76%, suggesting a negative feedback response to the expression of a constitutively active AT1AR. It remains unclear whether the decrease in endogenous AT1AR expression in the face of elevated transgenic N111G-AT1AR expression may have contributed to the level of arterial pressure in the model. Whereas mutants of AT1AR at the N111 position leads to constitutive activity, the receptors can still exhibit desensitization and internalization, which ultimately may limit their ability to initiate downstream signals (2, 3, 30). AT1R double mutants altering amino acids at positions 111 and 329 have been shown to exhibit reduced internalization and desensitization (6). Thus, it is possible that a larger effect on blood pressure may have been obtained if we had employed the 111/329 double mutant. Indeed, a knock-in mouse expressing the doubly mutant AT1R exhibited a 20 mmHg rise in blood pressure and an augmented pressor response to ANG II (7).

We hypothesized that a constitutively active AT1AR would not only raise baseline blood pressure, but would also augment the pressor response of exogenous ANG II, and that PCT-specific knockout of AT1AR would lessen the response. However, during high-dose ANG II infusion, blood pressure was increased to a similar extent in these mice as their nontransgenic controls. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to participate in the hypertensive action of infused ANG II, including arterial vasoconstriction, stimulation of sympathetic nervous system activity, release of aldosterone from the adrenal gland, and promotion of sodium reabsorption in both proximal and distal tubular segments (18). The results from the present study would suggest that ANG II action via the PCT AT1AR is not a significant component of the acute pressor action of increased circulating ANG II, but does contribute to the baseline level of blood pressure. This may be due to the fact that the PCT compartment is, at least partially, distinct from the systemic circulation. For example, proximal tubule luminal ANG II levels are significantly higher than that in the systemic circulation (31, 32), and are unaltered by volume expansion, a stimulus that robustly downregulated the systemic RAS (8). In addition, we have shown that proximal tubule-specific activation of the RAS increases blood pressure independent of systemic actions (13, 23). Moreover, the large decrease in endogenous AT1AR mRNA in whole kidney is remarkable given that the transgene was only expressed in the PCT, and thus may have been a compensatory response to limit the pressor action of enhanced ANG II signaling. Consistent with this, previous studies have shown that ANG II decreases the transcription rate of the AT1R by an AT1R-dependent mechanism and that binding of ANG II to the AT1R results in receptor internalization followed by degradation (33).

Given that the KAP2-AT1AR-N111G transgene is androgen responsive, it was surprising that male transgenic mice did not have a similar elevation in blood pressure, under baseline conditions, as testosterone-treated female mice. Because the strain of mice used (C57BL6) has been reported to have relatively low concentrations of testosterone in plasma (4, 9), we considered that the baseline circulating androgen concentration in the male mice might be insufficient to activate the transgene to the extent needed to detect a pressor response. Testosterone administration to male transgenic mice induced transgene expression to a level comparable to that in the similarly treated female but failed to change blood pressure. The reason for this is not clear, but may be due to a sex-specific difference in the response to increased ANG II signaling. In our experiment, we observed a decrease in renal AT2 receptor mRNA in female, but not in male transgenic mice (data not shown). In male mice, the maintenance of AT2R levels, and intact signaling via those receptors, may act as a buffer against the blood pressure raising actions of the AT1AR.

PCT-specific AT1AR depletion.

AT1AR knockout and renal transplantation studies have demonstrated that complete loss of AT1A receptors from the kidney reduces blood pressure by about 20 mmHg (11). This is not a uniform finding, as smaller decreases in SBP were reported in a different AT1AR-deficient mouse model (12). Herein we report a 12–13 mmHg decrease in arterial pressure in testosterone-treated female KAP2-iCRE X AT1ARFlox/Flox mice exhibiting PCT-specific AT1AR deficiency. The 70% decrease in AT1AR mRNA and the presence of a cre-recombined null allele in genomic DNA from the kidney supports the effectiveness and efficiency of the Cre-recombinase-mediated deletion. Surprisingly, however, there was no detectable decrease in ANG II radioligand binding in these mice, a finding that remains unexplained. This stands in contrast to the recent report by Gurley et al. (17) that tested the same hypothesis using a similar (but not identical) AT1aRFlox/Flox model bred with PEPCK-cre transgenic mice. Normally, the PEPCK gene is abundantly expressed in the liver, kidney, and adipose tissue, and thus under most circumstances, utilizing the PEPCK promoter as the driver for cre-recombinase would seem to be counterintuitive as it would target both hepatic and adipose AT1AR. Apparently, they employed a unique transgenic line that expresses cre-recombinase specifically in renal PCT cells (34). Indeed, they showed PCT-specific activity of the PEPCK-cre in the kidney, but did not report whether there was activity in other AT1AR expressing tissues that could influence arterial pressure. It is notable that use of the PEPCK promoter as a driver of Cre-recombinase led to much more effective ablation (40%) of AT1R binding sites in the renal cortex when compared with two control mice than it was in our study employing the androgen-responsive KAP promoter. Interestingly, despite this important difference, both groups likewise measured a 10 mmHg decrease in baseline arterial pressure. Gurley et al. (17) extended their study by reporting that PCT AT1AR regulates fluid reabsorption and PCT AT1AR-deficient mice are protected from ANG II-induced hypertension. Future studies would have to be performed to assess whether PCT AT1AR deficiency using the KAP2-iCre model is similarly effective in protecting from ANG II or other forms of hypertension.

In a further point of similarity between the studies, there was no change in expression of NHE3, the sodium phosphate cotransporter (NaPi2), subunits of the epithelial sodium channel, or the sodium potassium ATPase under baseline conditions. We noted a significant decrease in expression of several subunits of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) in our PCT AT1AR-deficient mice. Interestingly, Gurley et al. (17) reported changes in the abundance of NHE3 in response to ANG II infusion, an effect augmented by PCT-specific AT1AR ablation. Thus, whereas PCT AT1AR deficiency may not alter the abundance of major renal sodium transporters under baseline conditions, PCT AT1AR may play important roles as regulators of renal transporters under conditions of AT1AR activation or under other pathological conditions. In our study, it remains unclear whether the modest decreases in ACE and AT2R mRNAs in the kidney of PCT-AT1AR-deficient mice played a mechanistic role in the regulation of arterial pressure.

Limitations of the study and remaining questions.

One of the most obvious limitations to our study was the apparent expression of the transgene in extra-renal tissues such as the ovary and brain. Although the consequences of ovarian expression of constitutively active AT1AR remains undefined, its expression in the brain could have obvious consequences for the regulation of arterial pressure. Remarkably, the chimeric KAP promoter (termed KAP2) originally developed by us (5) has been used by us and others to target PPARα (28), AGT (37), and renin (23) without notable expression in the brain. AT1 receptors in the brain have long been known to be an important regulator of arterial pressure, hydromineral balance, vasopressin release, and sympathetic drive, and therefore a contribution of brain AT1AR in the KAP2-AT1AR-N111G model cannot be excluded. In the case of the KAP2-N111G-AT1AR transgenic model, expression of the transgene in the brain led to increased expression of AT2 receptors in the brain. AT2 receptors largely counterbalance the effects of the AT1R. For example, intracerebroventricular injection of the AT2R antagonist PD123319 augments the pressor response to central ANG II, and the pressor response to intracerebroventricular ANG II is augmented in AT2R-deficient mice (29). Thus, overexpression of AT2R in the brain may have had the effect of diminishing arterial pressure in the overexpression model. On the contrary, there was no evidence of Cre-mediated recombination in the brain of the PCT-specific knockout mice, nor any change in expression of other RAS genes. Although, we originally reported low level expression of Cre-recombinase mRNA in the brain of KAP2-iCRE transgenic mice, we could not detect evidence of Cre-mediated recombination in the brain of KAP2-iCRE X ROSA mice (27).

Perspectives and Significance

In summary, our study using two different experimental mouse models has demonstrated that AT1AR in the renal PCT per se are regulators of systemic blood pressure. This finding, confirmed by a recent study also examining the importance of renal PCT AT1A receptors (17), provides additional support for the concept that ANG II regulates blood pressure through its combined actions in multiple sites including the peripheral circulation and local sites of action, such as the renal tubules. This is supported by evidence from our laboratory (13, 23), and collaborative studies with the Navar, Kobori, and Cook laboratories (22, 36) showing that renal-specific expression of the RAS can have effects on systemic arterial pressure without effecting the levels of circulating angiotensin peptides. Further studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of how PCT AT1AR regulates blood pressure and how it effects AT1 and AT2 receptors in the kidney, and elsewhere, under normal and pathological conditions.

GRANTS

Transgenic mice were generated at the University of Iowa Transgenic Animal Facility supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and from the Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine. This work was also supported through research grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to C. D. Sigmund (HL-084207, HL-048058, and HL-061446), L. A. Cassis (HL-073085), and A. Daugherty (HL-062846 and HL-080100), and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council to A. M. Allen (566563). J. L. Grobe was supported by a K99/R00 “Pathway to Independence” award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-098276). H. Li was supported through a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the generous research support of the Roy J. Carver Trust.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the University of Iowa Animal Care and Veterinary staff for their assistance in this project. We also thank Norma Sinclair, Patricia Yarolem, and Joanne Schwarting for their technical expertise in generating transgenic mice, and Jaspreet Bassi for technical assistance with receptor autoradiography.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allen AM, Dosanjh JK, Erac M, Dassanayake S, Hannan RD, Thomas WG. Expression of constitutively active angiotensin receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla increases blood pressure. Hypertension 47: 1054–1061, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Auger-Messier M, Arguin G, Chaloux B, Leduc R, Escher E, Guillemette G. Down-regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in cells stably expressing the constitutively active angiotensin II N111G-AT(1) receptor. Mol Endocrinol 18: 2967–2980, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Auger-Messier M, Clement M, Lanctot PM, Leclerc PC, Leduc R, Escher E, Guillemette G. The constitutively active N111G-AT1 receptor for angiotensin II maintains a high affinity conformation despite being uncoupled from its cognate G protein Gq/11α. Endocrinology 144: 5277–5284, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartke A. Increased sensitivity of seminal vesicles to testosterone in a mouse strain with low plasma testosterone levels. J Endocrinol 60: 145–148, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bianco RA, Keen HL, Lavoie JL, Sigmund CD. Untraditional methods for targeting the kidney in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F1027–F1033, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Billet S, Bardin S, Tacine R, Clauser E, Conchon S. The AT1A receptor “gain-of-function” mutant N111S/delta329 is both constitutively active and hyperreactive to angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E840–E848, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Billet S, Bardin S, Verp S, Baudrie V, Michaud A, Conchon S, Muffat-Joly M, Escoubet B, Souil E, Hamard G, Bernstein KE, Gasc JM, Elghozi JL, Corvol P, Clauser E. Gain-of-function mutant of angiotensin II receptor, type 1A, causes hypertension and cardiovascular fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest 117: 1914–1925, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boer WH, Braam B, Fransen R, Boer P, Koomans HA. Effects of reduced renal perfusion pressure and acute volume expansion on proximal tubule and whole kidney angiotensin II content in the rat. Kidney Int 51: 44–49, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brouillette J, Rivard K, Lizotte E, Fiset C. Sex and strain differences in adult mouse cardiac repolarization: importance of androgens. Cardiovasc Res 65: 148–157, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cervenka L, Wang CT, Mitchell KD, Navar LG. Proximal tubular angiotensin II levels and renal functional responses to AT1 receptor blockade in nonclipped kidneys of Goldblatt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 33: 102–107, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Oliverio MI, Pazmino AK, Griffiths R, Flannery PJ, Spurney RF, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM. Distinct roles for the kidney and systemic tissues in blood pressure regulation by the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 115: 1092–1099, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daugherty A, Rateri DL, Lu H, Inagami T, Cassis LA. Hypercholesterolemia stimulates angiotensin peptide synthesis and contributes to atherosclerosis through the AT1A receptor. Circulation 110: 3849–3857, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davisson RL, Ding Y, Stec DE, Catterall JF, Sigmund CD. Novel mechanism of hypertension revealed by cell-specific targeting of human angiotensinogen in transgenic mice. Physiol Genomics 1: 3–9, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ding Y, Davisson RL, Hardy DO, Zhu LJ, Merrill DC, Catterall JF, Sigmund CD. The kidney androgen-regulated protein (KAP) promoter confers renal proximal tubule cell-specific and highly androgen-responsive expression on the human angiotensinogen gene in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 272: 28142–28148, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ding Y, Sigmund CD. Androgen-dependent regulation of human angiotensinogen expression in KAP-hAGT transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F54–F60, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Groblewski T, Maigret B, Larguier R, Lombard C, Bonnafous JC, Marie J. Mutation of Asn111 in the third transmembrane domain of the AT1A angiotensin II receptor induces its constitutive activation. J Biol Chem 272: 1822–1826, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gurley SB, Riquier-Brison AD, Schnermann J, Sparks MA, Allen AM, Haase VH, Snouwaert JN, Le TH, McDonough AA, Koller BH, Coffman TM. AT1A angiotensin receptors in the renal proximal tubule regulate blood pressure. Cell Metab 13: 469–475, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hall JE. Control of sodium excretion by angiotensin II: intrarenal mechanisms and blood pressure regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 250: R960–R972, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris PJ, Young JA. Dose-dependent stimulation and inhibition of proximal tubular sodium reabsorption by angiotensin II in the rat kidney. Pflügers Arch 367: 295–297, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG, Ho MM, Vinson GP, el-Dahr SS. Immunohistochemical localization of ANG II AT1 receptor in adult rat kidney using a monoclonal antibody. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F170–F177, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev 59: 251–287, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Satou R, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Hase N, Suzaki Y, Sigmund CD, Navar LG. Kidney-specific enhancement of ANG II stimulates endogenous intrarenal angiotensinogen in gene-targeted mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F938–F945, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lavoie JL, Lake-Bruse KD, Sigmund CD. Increased blood pressure in transgenic mice expressing both human renin and angiotensinogen in the renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F965–F971, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lavoie JL, Liu X, Bianco RA, Beltz TG, Johnson AK, Sigmund CD. Evidence supporting a functional role for intracellular renin in the brain. Hypertension 47: 461–466, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Le TH, Kim HS, Allen AM, Spurney RF, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Physiological impact of increased expression of the AT1 angiotensin receptor. Hypertension 42: 507–514, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Le TH, Oliverio MI, Kim HS, Salzler H, Dash RC, Howell DN, Smithies O, Bronson S, Coffman TM. A γGT-AT1A receptor transgene protects renal cortical structure in AT1 receptor-deficient mice. Physiol Genomics 18: 290–298, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li H, Zhou X, Davis DR, Xu D, Sigmund CD. An androgen-inducible proximal tubule-specific Cre recombinase transgenic model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1481–F1486, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li S, Nagothu KK, Desai V, Lee T, Branham W, Moland C, Megyesi JK, Crew MD, Portilla D. Transgenic expression of proximal tubule peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α in mice confers protection during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 76: 1049–1062, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Z, Iwai M, Wu L, Shiuchi T, Jinno T, Cui TX, Horiuchi M. Role of AT2 receptor in the brain in regulation of blood pressure and water intake. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H116–H121, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miserey-Lenkei S, Parnot C, Bardin S, Corvol P, Clauser E. Constitutive internalization of constitutively active agiotensin II AT1A receptor mutants is blocked by inverse agonists. J Biol Chem 277: 5891–5901, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Navar LG, Imig JD, Wang CT. Intrarenal production of angiotensin II. Sem Nephrol 17: 412–422, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Navar LG, Lewis L, Hymel A, Braam B, Mitchell KD. Tubular fluid concentrations and kidney contents of angiotensins I and II in anesthetized rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1153–1158, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ouali R, Berthelon MC, Begeot M, Saez JM. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes AT1 and AT2 are down-regulated by angiotensin II through AT1 receptor by different mechanisms. Endocrinology 138: 725–733, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rankin EB, Tomaszewski JE, Haase VH. Renal cyst development in mice with conditional inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Cancer Res 66: 2576–2583, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rateri DL, Moorleghen JJ, Balakrishnan A, Owens APIII, Howatt DA, Subramanian V, Poduri A, Charnigo R, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Endothelial cell-specific deficiency of ANG II type 1a receptors attenuates ANG II-induced ascending aortic aneurysms in LDL receptor−/− mice. Circ Res 108: 574–581, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Redding KM, Chen BL, Singh A, Re RN, Navar LG, Seth DM, Sigmund CD, Tang WW, Cook JL. Transgenic mice expressing an intracellular fluorescent fusion of angiotensin II demonstrate renal thrombotic microangiopathy and elevated blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1807–H1818, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang SL, Liu F, Hsieh TJ, Brezniceanu ML, Guo DF, Filep JG, Ingelfinger JR, Sigmund CD, Hamet P, Chan JS. RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int 69: 1016–1023, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Song K, Allen AM, Paxinos G, Mendelsohn FAO. Mapping of angiotensin II receptor subtype heterogeneity in rat brain. J Comp Neurol 316: 467–484, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang X, Armando I, Upadhyay K, Pascua A, Jose PA. The regulation of proximal tubular salt transport in hypertension: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 412–420, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.