Abstract

Aerobic oxidation reactions have been the focus of considerable attention, but their use in mainstream organic chemistry has been constrained by limitations in their synthetic scope and by practical factors, such as the use of pure O2 as the oxidant or complex catalyst synthesis. Here, we report a new (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system that enables efficient and selective aerobic oxidation of a broad range of primary alcohols, including allylic, benzylic and aliphatic derivatives, to the corresponding aldehydes using readily available reagents, at room temperature with ambient air as the oxidant. The catalyst system is compatible with a wide range of functional groups and the high selectivity for 1° alcohols enables selective oxidation of diols that lack protecting groups.

Introduction

The oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes, ketones and carboxylic acids is among the most important and widely used class of oxidation reactions in organic chemical synthesis. Numerous classical reagents and methods are available for these reactions,1 including chromium2 and manganese3 oxides, “activated DMSO” methods,4 and hypervalent iodine reagents,5 which are well-suited for small-scale applications; and pyridine·SO36 and NaOCl/TEMPO (TEMPO = 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxyl),7 which are frequently employed in large-scale applications. In recent years, there has been growing demand for new environmentally benign methods suitable for large-scale applications, particularly within the pharmaceutical industry.8 Molecular oxygen is an ideal oxidant, and significant progress has been made in the development of catalytic methods for aerobic alcohol oxidation.9 Nevertheless, key challenges must be addressed in order for such reactions to find widespread use in the synthesis of complex molecules. Large-scale applications of aerobic alcohol oxidation are constrained by safety concerns associated with the combination of O2 and organic solvents and reagents,8a,b as well as the frequent use of halogenated solvents.8b On laboratory scale, existing aerobic alcohol oxidation reactions often have more-limited scope and offer few, if any, synthetic advantages over traditional reagents and methods. Practical considerations also limit the use of aerobic reactions on small scale. For example, few synthetic labs routinely stock O2 gas cylinders needed for reactions that require pure O2 as the oxidant; oxidation methods optimized with non-standard solvents, such as fluorinated arenes or ionic liquids, are less likely to be evaluated in routine synthetic applications; and some of the catalysts with the best reported activity are not commercially available, they must be independently synthesized, and/or they have limited shelf-life.10,11 Limitations such as these hinder widespread adoption of aerobic oxidation reactions in synthetic chemistry.

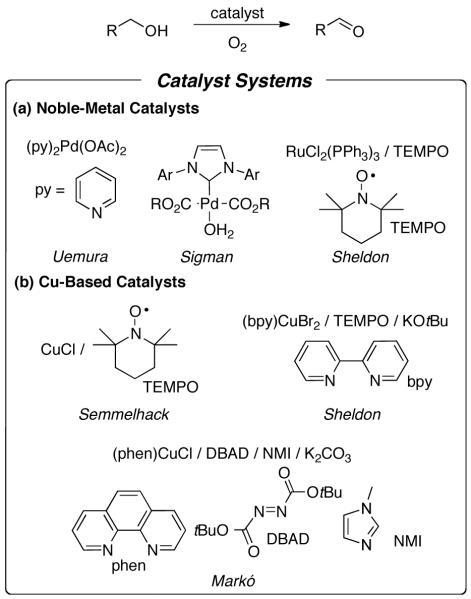

Many of the recently developed catalyst systems for aerobic alcohol oxidation are based on coordination complexes of noble metals, such as Pd12,13 and Ru14 (Scheme 1a). These catalysts are effective with a variety of alcohols, including 1° and 2° allylic, benzylic and aliphatic substrates; however, they are often inhibited by heterocycles and other nitrogen-, oxygen-, and sulfur-containing functional groups and can promote competing oxidation of other functional groups (e.g., Pd catalysts oxidize alkenes15). In addition, they typically use pure O2 (1 atm) as the oxidant. In recent years, we have performed mechanistic studies of Pd-based catalysts16 and explored their potential use in largescale applications,17 but the limitations on the synthetic scope of these systems prompted us to consider other options in our pursuit of practical aerobic alcohol oxidation methods.

Scheme 1.

Representative Catalyst Systems for Aerobic Oxidation of Primary Alcohols.

First-row transition metals tend to undergo more-facile ligand exchange, and empirical data suggest aerobic alcohol oxidation catalysts derived from these metals exhibit broader functional-group compatibility (e.g., Cu,18,19 Co,20 Fe21 and V22). Copper-based catalyst systems, particularly those employing TEMPO18 or a dialkylazodicarboxylate19 as redox-active cocatalysts (Scheme 1b), have emerged as some of the most effective catalysts.23 One of the earliest examples is a CuCl/TEMPO catalyst system reported by Semmelhack and coworkers in 1984,18a which was shown to be effective for the oxidation of 1° benzylic and allylic alcohols. Oxidation of aliphatic alcohols required the use of stoichiometric CuCl2 (2.2 equiv). Sheldon and coworkers developed a related catalyst system capable of using ambient air as the oxidant, which consisted of a CuII salt with 2,2′-bipyridine (bpy) as a ligand and KOtBu as a base.24 The reduced reactivity of aliphatic alcohols was again noted, and 1-octanol was the only successful example reported, employing a higher temperature and catalyst loading to achieve full conversion.25 Some progress in the oxidation of aliphatic alcohols was reported recently by Koskinen et al, albeit still using pure O2 as the oxidant.25c Another Cu/TEMPO catalyst system, introduced by Knochel and coworkers, uses fluorous biphasic conditions in combination with a fluoroalkyl-substituted bpy ligand.18b Independently, Markó and coworkers have developed a series of catalyst systems for aerobic alcohol oxidation employing (phen)CuCl (phen = 1,10-phenanthroline) as the catalyst, in combination with dialkylazodicarboxylates as redox-active cocatalysts.9e,19 These reactions exhibit the broadest scope of aerobic alcohol oxidation reported to date, successfully oxidizing a wide range of diversely functionalized 1° and 2° allylic, benzylic and aliphatic alcohols. Despite the advantages of these reactions, the use of pure O2 as the oxidant and fluorobenzene as the optimal solvent has limited their use in traditional synthetic chemistry applications.

The oxidation of primary aliphatic alcohols to aldehydes is among the most synthetically important classes of alcohol oxidation reactions, but it is also among the most challenging. As already noted, aliphatic alcohols are less reactive than allylic and benzylic substrates, and the aliphatic aldehyde products are also more susceptible to over-oxidation to the carboxylic acids. Here, we report a new, highly active (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system that effects selective aerobic oxidation of a broad range of primary alcohols, including allylic, benzylic and aliphatic derivatives, to the corresponding aldehydes. The reactions proceed in high yield, exhibit broad functional-group compatibility and achieve chemoselective formation of aldehydes with negligible overoxidation to the carboxylic acids. Furthermore, the reactions exhibit exquisite selectivity for 1° over 2° alcohols, enabling selective oxidation of diols, without requiring the use of protecting groups. The use of a traditional organic solvent (acetonitrile), and the ability to carry out most of the reactions at room temperature with ambient air as the oxidant greatly enhances the practicality of these methods. Overall, the utility of these methods rivals or surpasses that of traditional laboratory-scale alcohol oxidation reactions. The development, scope and limitations of these methods are elaborated below.

Results and Discussion

Optimization of a new (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system

In the course of studying Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions, we attempted to prepare the aldehyde derived from the primary alcohol trans-4-hexen-1-ol via aerobic oxidation with a Pd(OAc)2/pyridine13a catalyst system. Only a low yield (5%) of the desired aldehyde was obtained, however, and little improvement (14% yield) was achieved by using the Ru(PPh3)3Cl2/TEMPO14b catalyst system (cf. Scheme 1a). Anticipating that first-row transition-metal catalysts of this type should be less susceptible to inhibition by the alkene in this substrate, we focused our attention on previously reported Cu-based catalyst systems described above. In addition, we targeted reactions performed at room temperature with ambient air as the source of oxidant.

To identify an efficient catalyst system that meets the criteria outlined above, we evaluated conditions related to those published previously by Semmelhack (CuCl/TEMPO),18a Sheldon ((bpy)CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu),24 and Markó (CuCl/phen/DBAD)19 (Table 1; see Supporting Information for full screening data). The Cu source, cocatalyst (TEMPO or DBAD), base, and solvent were varied, while the use of ambient temperature and air as the oxidant was retained throughout. Testing of the three previous catalysts, and modification of the Markó catalyst system using non-halogenated solvents, led to low product yields under the ambient conditions (0–36%; entries 1–5). Significant improvements were observed upon modifying the Sheldon catalyst system, specifically by replacing KOtBu with N-methylimidazole (NMI) and using acetonitrile as the solvent, without including water as a cosolvent. CuBr2 and CuBr were effective copper sources for small-scale reactions, such as those in Table 1, but they were not always reliable in larger scale reactions. For example, the reactions would occasionally form insoluble precipitates and fail to reach completion within 24 h. The use of CuI salts with non-coordinating anions (e.g., CuI(OTf)) as the catalyst afforded the desired aldehyde in quantitative yield, based on GC analysis (Table 1, entry 12). Reactions employing Cu(OTf) remained homogeneous throughout, and the results were highly reproducible on larger scales (see below).

Table 1.

Optimization of Cu/TEMPO Catalyst System for the Oxidation of trans-4-hexen-1-ol.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Cu salt (5 mol %) |

ligand (5 mol %) |

cocatalyst (5 mol %) |

base | mol % | solvent | yielda |

| 1 | CuClb | none | TEMPOb | none | DMF | 29% | |

| 2 | CuBr2 | bpy | TEMPO | KOtBu | 5 | MeCN/H2O | 33% |

| 3 | CuCl | phen | DBAD | KOtBu NMI |

5 7 |

PhCF3 | 36% |

| 4 | CuCl | phen | DBAD | KOtBu NMI |

5 7 |

toluene | 26% |

| 5 | CuCl | phen | DBAD | KOtBu NMI |

5 7 |

MeCN/H2O | NDc |

| 6 | CuCl | phen | TEMPO | KOtBu NMI |

5 7 |

MeCN/H2O | 12% |

| 7 | CuCl | bpy | TEMPO | KOtBu NMI | 5 7 |

MeCN/H2O | 85% |

| 8 | CuCl | bpy | TEMPO | KOtBu | 5 | MeCN/H2O | 11% |

| 9 | CuCl2 | bpy | TEMPO | KOtBu | 5 | MeCN/H2O | 14% |

| 10 | CuBr2 | bpy | TEMPO | NMI | 7 | MeCN | 95% |

| 11 | CuBr | bpy | TEMPO | NMI | 7 | MeCN | 98% |

| 12 | Cu(OTf) | bpy | TEMPO | NMI | 10 | MeCN | 100% |

| 13 | Cu(OTf)2 | bpy | TEMPO | NMI | 10 | MeCN | NDc |

| 14 | Cu(OTf) | bpy | TEMPO | none | MeCN | 92% | |

| 15 | Cu(OTf) | none | TEMPO | NMI | 10 | MeCN | 68% |

| 16 | Cu(OTf) | bpy | none | NMI | 10 | MeCN | NDc |

Yields were determined by GC analysis and are based on the ratio of product/(product + starting material).

10 mol %.

No product detected.

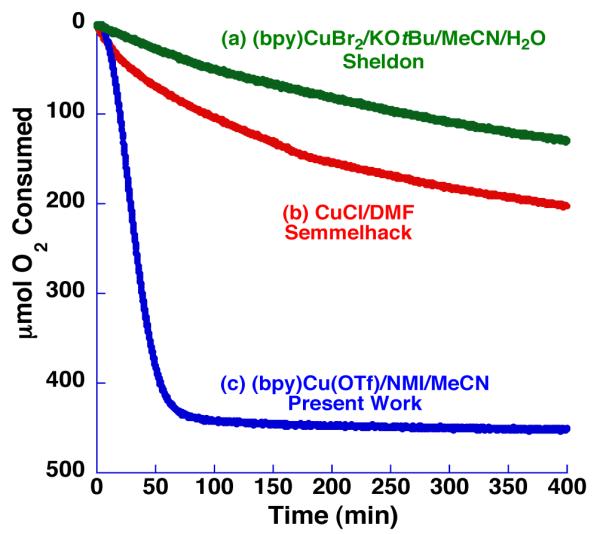

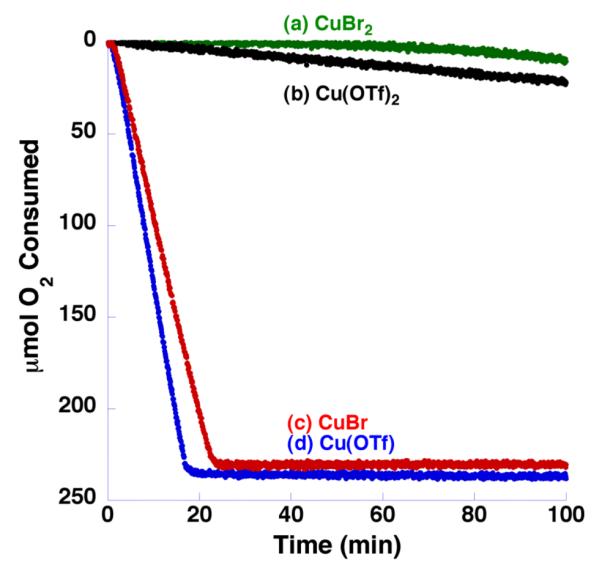

The dramatic improvement in catalytic activity with this (bpy)CuI(OTf)/TEMPO system over related catalyst systems is apparent from a comparison of their gas-uptake kinetic profiles for the oxidation of 1-octanol (Figure 1; 1 atm of O2 was used in these experiments). As shown in the time course plot, the new catalyst system enables complete conversion of this aliphatic alcohol within approximately 1 h at room temperature. A 10-15 min induction period is observed at the start of the reaction, the mechanistic origin of which is currently under investigation. Qualitatively, we observe that the initial oxidation state of the copper catalyst has a major impact on the reaction efficiency (Figure 2), with CuI salts exhibiting much higher reactivity. Sheldon and Koskinen have also noted the beneficial effect of non-coordinating anions with CuII-based catalyst systems.24b,25c It is reasonable to expect that Cu cycles between +1 and +2 oxidations states during the catalytic mechanism, so the origin of the dramatic difference in rates using CuI vs CuII precursors is not clear. Ongoing mechanistic studies are focused on elucidating the origin of this unusual effect.

Figure 1.

Comparison of three different Cu/TEMPO catalyst systems in the aerobic oxidation of 1-octanol (1.0 mmol) at 27 °C. Catalyst systems include the following: (a) “Sheldon conditions”24 (similar to Table 1, entry 2): CuBr2 (5 mol %), bpy (5 mol %), TEMPO (5 mol %), and KOtBu (5 mol %) in 2:1 MeCN:H2O (0.67 M) ( , green); (b) “Semmelhack conditions”18a (similar to Table 1, entry 1): CuCl (10 mol %) and TEMPO (10 mol %) in DMF (0.4 M) (

, green); (b) “Semmelhack conditions”18a (similar to Table 1, entry 1): CuCl (10 mol %) and TEMPO (10 mol %) in DMF (0.4 M) ( , red); and (c) Cu(OTf) (5 mol %), bpy (5 mol %), TEMPO (5 mol %), and NMI (10 mol %) in MeCN (0.2 M) (

, red); and (c) Cu(OTf) (5 mol %), bpy (5 mol %), TEMPO (5 mol %), and NMI (10 mol %) in MeCN (0.2 M) ( , blue). See the Supporting Information for additional details.

, blue). See the Supporting Information for additional details.

Figure 2.

Effect of Cu source on the rate of aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol (0.5 mmol) at 27 °C. The Cu source (5 mol %) was combined with TEMPO (5 mol %), NMI (10 mol %), and bpy (5 mol %) with [Cu] = (a) CuBr2 ( , green), (b) Cu(OTf)2 (

, green), (b) Cu(OTf)2 ( , black), and (c) CuBr (

, black), and (c) CuBr ( , red), and (d) Cu(OTf) (

, red), and (d) Cu(OTf) ( , blue). Reactions employing CuBr2 consistently exhibit a long induction period. See the Supporting Information for additional details.

, blue). Reactions employing CuBr2 consistently exhibit a long induction period. See the Supporting Information for additional details.

Scope and functional group tolerance of (bpy)CuI/TEMPO-catalyzed alcohol oxidation

In a preliminary effort to assess the potential scope and utility of this catalyst system, the oxidation of a small series of aliphatic alcohols with various functional groups was examined (Table 2). A broader context for the results was provided by investigating the same substrates with two of the most effective noble-metal catalyst systems that have been reported in the literature: Pd(OAc)2/pyridine,13a and RuCl2(PPh3)3/TEMPO,14b as well as the (bpy)CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu catalyst system.24a Reactions performed with catalysts from the literature used the conditions reported with the broadest substrate scope (see Table 2 for details). The data highlight the efficiency and broad functional-group compatibility of the new (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst. Good-to-excellent product yields were obtained with subtrates containing a number of coordinating functional groups, including alkynes, heterocycles, ethers and thioethers. These data amplify the higher activity of the (bpy)CuI/TEMPO/NMI catalyst system relative to the previous (bpy)CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu in the oxidation of aliphatic alcohols. The improved functional-group tolerance of the (bpy)CuI/TEMPO/NMI catalyst system relative to the noble-metal catalyst systems is clearly evident from the data in entries 2–6.

Table 2.

Comparison of Known Catalyst Systems for Aerobic Alcohol Oxidation in the Oxidation of Alcohols Bearing Functional Groups.a

| entry | aldehyde | Pd(OAc)2/py | RuCl2(PPh3)3 TEMPO |

CuBr2/KOtBu TEMPO |

Cu(I)/NMI TEMPOa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

93% | 71% | 56% | >98% |

| 2 |

|

<5% | 43% | 47% 52%b |

>98% |

| 3 |

|

23% | 24% | 33% | 97% |

| 4 |

|

26% | 53% | 29% | 85% c |

| 5 |

|

<5% | 14% | <5% | 76% |

| 6 |

|

12% | 7% | 28% | >98% |

Reaction conditions: Pd(OAc)2/pyridine13a: alcohol (0.20 mmol, 0.1 M in toluene), Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol %), py (20 mol %), 3Å MS (100 mg), O2 balloon, 80 °C, 2 h; RuCl2(PPh3)3/TEMPO14b: alcohol (0.50 mmol, 0.5 M in toluene), RuCl2(PPh3)3 (2 mol %), TEMPO (12 mol %), O2 balloon, 100 °C, 7 h; CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu24a: alcohol (0.25 mmol, 0.17 M in 2:1 MeCN:H2O), CuBr2 (5 mol %), bpy (5 mol %) TEMPO (5 mol %), KOtBu (5 mol %); CuI/TEMPO/NMI: alcohol (0.25 mmol, 0.2 M in MeCN), Cu(OTf), bpy (5 mol %), TEMPO (5 mol %), NMI (10 mol %), rt.

40°C with 7.5 mol % TEMPO

1 atm O2 in place of air. Yields were determined by GC analysis and are based on the ratio of product/(product + starting material). Low yields primarily reflect incomplete conversion of starting material.

These preliminary data provided the basis for more-thorough analysis of the substrate scope, and a number of different benzylic, aliphatic, allylic, and propargylic alcohols undergo efficient reaction with this (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system (Table 3). No oxidation of the alkene or alkyne is observed, even if the product remains in the reaction mixture after completion of the reaction. The method is compatible with a Me3Si-terminated alkyne (entry 12). Purification of this aldehyde results in a reduced yield; however, the product was obtained in 86% yield with 95% purity following workup of the crude reaction mixture.

Table 3.

Scope of (bpy)CuI/TEMPO-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidation of Hydrocarbon-Containing Alcohols to Aldehydes.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | aldehyde | time | comments | yielda |

| 1 |

|

3 h | 95% | |

| 2 |

|

22 h 23 h |

X = OTf− BF4− |

>98% 98% |

| 3 |

|

24 h 11 h |

air bal. O2 bal. |

92% 88% |

| 4 |

|

24 h 11 h |

air bal. O2 bal. |

83% 98% |

| 5 |

|

6 h 4 h |

1 mmol 10 mmol |

>98% 97% |

| 6 |

|

24 h | >20:1 dr | >98% |

| Alkenes and Alkynes | ||||

| 7 |

|

2 h | 92% | |

| 8 |

|

3 h 4 h |

X = OTf− BF4− PF6− |

>98% >99% 97% |

| 9 |

|

2 h | 20:1 Z:E | >98% |

| 10 |

|

24 h 24 h 5 h |

air air bal. O2 bal. |

72% 88% 92% |

| 11 |

|

2 h | >98% | |

| 12 |

|

24 h | (86%)b 65% |

|

Yields given are for isolated material.

Yield of crude reaction product, 95% purity by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Functionalized alcohols also undergo facile oxidation to the corresponding aldehydes (Table 4). Alcohols containing esters, ethers and thioethers (entries 1, 3, 4, 5 and 10), oxygen-, nitrogen- and sulfur-containing heterocycles (entries 2, 6, 7, and 11), as well as alcohols with an unprotected aniline (entry 8) and a Boc-protected secondary amine (entry 9) undergo efficient oxidation in excellent yields. Aryl halides, including those with ortho iodo substituents, are also compatible with the reaction conditions (entries 12-15). Some alcohols (e.g., Table 4, entries 5, 6, and 9) did not reach completion within 24 h at ambient temperature; however, full conversion was achieved in this time period by performing the reaction at 50 °C.26

Table 4.

Scope of (bpy)CuI/TEMPO-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidation of Heteroatom-Containing Alcohols to Aldehydes.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | aldehyde | time | comments | yielda |

| Oxygen | ||||

| 1 |

|

2.5 h 1.5 h |

1 mmol 50 mmol |

>98% 96% |

| 2 |

|

3 h | 83% | |

| 3 |

|

5 h | >98% | |

| 4 |

|

1.5 h | 19:1 Z:E | >98% |

| 5 |

|

24 h | 50 °C >98 : 2 dr |

>98% |

| 6 |

|

24 h | 50 °C O2 bal. |

(79%)b 47% |

| Nitrogen | ||||

| 7 |

|

3 h | 95% | |

| 8 |

|

3 h 4 h |

X = OTf− BF4− |

>98% >98% |

| 9 |

|

21 hc | 50 °C >20:1 erc |

>98% |

| Sulfur | ||||

| 10 |

|

24 h | (78%)d 25% |

|

| 11 |

|

3 h | 83% | |

| Aryl Halides | ||||

| 12 |

|

5 h | 94% | |

| 13 |

|

1 h | 96% | |

| 14 |

|

1.5 h | 96% | |

| 15 |

|

3 h | >98% | |

Isolated yields.

Yield determined by 1H NMR spectrocopy and is based on the ratio of product/(product + starting material).

Enantiomeric ratio based on 1H NMR determination of the diastereomeric ratio of derivatized product, full details given in SI.

Yield of crude reaction product, 94% purity by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

The mildness of the reaction conditions is evident by the lack of epimerization of the α-stereocenter of the prolinal product (Table 3, entry 9) and the two formylcyclohexane derivatives (Table 3, entry 6 and Table 4, entry 5). Moreover, we observe near-complete retention of cis-alkene stereochemistry in the oxidation of cis-allylic alcohols (Table 3, entry 9 and Table 4, entry 4). Aldehyde products derived from the latter reactions are highly susceptible to isomerization, even under mildly basic conditions.27

This new (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system has many appealing practical characteristics. Most of the reactions were carried out in open reaction vessels employing ambient air as the source of oxidant. In some cases, low-boiling aldehydes can be lost to evaporation over the course of the reaction, in which case a balloon of house air (or O2) enables the aldehydes to be obtained in high yields (Table 3, entries 3, 4, and 10). In addition, separation and isolation of the aldehyde is very straightforward, in most cases requiring only filtration of the reaction mixture through a silica plug or an aqueous extraction to remove the Cu salts to provide aldehyde product that is pure, based on 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis. Reproducibly high yields of aldehyde following these procedures could be obtained on scales up to 50 mmol (Table 3, entry 5 and Table 4, entry 1). Finally, the CuI catalyst is commercially available with several non-coordinating anions (OTf−, BF4−, and PF6−), each of which proved effective in the reactions (Table 3, entry 8).

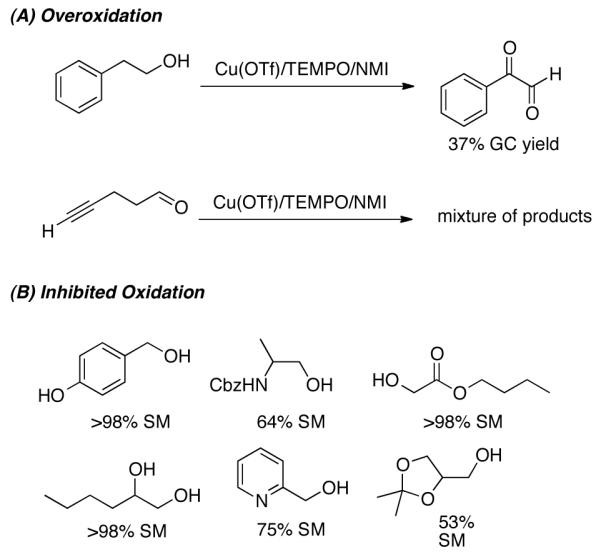

Some limitations were identified in the course of these studies. For example, a homobenzylic alcohol underwent oxygenation at the benzylic position to afford the corresponding α-ketoaldehyde in low yield, and a terminal alkyne reacted to form a complex mixture of products (Figure 3A). Vicinal diols and other 1° alcohols bearing vicinal chelating groups (e.g., ethers, amines, and esters), and substrates with phenol substituents proved to be less reactive and led to incomplete conversion of the starting material (SM) (Figure 3B). The latter limitations probably arise from chelation of the adjacent functional group or preferential formation of an unreactive Cu-phenolate species. That similar limitations are not evident with other TEMPO and related nitroxyl-based alcohol oxidation reactions (e.g., TEMPO/NaOCl)7a,11 suggest that these observations are associated with the Cu-based catalyst system.

Figure 3.

Limitations of (bpy)CuI/TEMPO oxidation system due to (A) overoxidation and (B) inhibited oxidation.

Chemoselective Oxidation of Unprotected Diols by (bpy)CuI/TEMPO

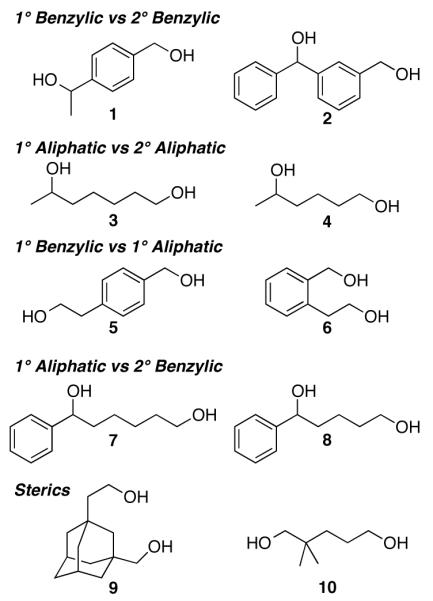

The studies outlined above reveal that most primary alcohols undergo very efficient oxidation with this catalyst system. These results, together with the very poor reactivity of secondary alcohols (data not shown), suggested that it might be possible to achieve chemoselective oxidation of unprotected diols containing 1° and/or 2° alcohols with the (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst. Such reactivity has very limited precedent, even with traditional oxidants for alcohol oxidation, and selective oxidation of diols often requires the use of protecting groups. In cases where selectivity has been observed (e.g., with halogen, hypervalent iodine and peroxide-based reagents), 2° alcohols typically react more readily.28,29 Few methods exist for the selective oxidation of a 1° alcohol within a diol. The best examples employ stoichiometric OsO4,30 stoichiometric RuCl2(PPh3)3,31 or Br2 with a Ni(O2CPh)2 catalyst.32 Sheldon et al. reported selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol in an intermolecular competition experiment with 2-octanol or 2-phenyl ethanol using their (bpy)CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu catalyst system.24b Intramolecular competition studies with substrates containing both 1° and 2° alcohols were not investigated. Our efforts to explore the chemoselective oxidation of diols were based on a series of substrates (1-10) that exhibit specific selectivity challenges, including the oxidation of 1° versus 2° alcohols, aliphatic versus benzylic alcohols, and sterically differentiated 1° alcohols (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

Unprotected Diol Substrates Examined for Selective Oxidation.

Initial studies focused on substrates 1, 3, 8 and 10, and we tested their reactivity with the (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system and the three previously reported catalyst systems tested above: Pd(OAc)2/pyridine, RuCl2(PPh3)3/TEMPO, and CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu (Table 5). The Pd(OAc)2/pyridine catalyst shows essentially no selectivity for any of these substrates. The Ru catalyst system is moderately selective for oxidation of the less-hindered 1° alcohol in substrates 1, 3 and 10; however, competing oxidation of the 2° benzylic alcohol is observed with substrate 8. As noted in the introduction, the (bpy)CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu catalyst system also shows a preference for oxidation of less-hindered 1° alcohols; however, it is substantially less reactive than the new (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system. The latter catalyst affords very good product yields, in all cases leading to products that reflect oxidation of the least hindered alcohol. Building upon these results, we investigated the full scope of substrates 1–10 in order to assess the preparative utility of these reactions.

Table 5.

Comparison of Different Catalyst Systems in the Aerobic Oxidation of Unprotected Diols.a

| diol | aldehyde product | ketone product | overoxidation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Pd(OAc)2/py (13 min, 80 °C) | 41% | 32% | 12% | 15% |

| RuCl2(PPh3)3/TEMPO (7 h, 100 °C) | <1% | 75% | <1% | 19% |

| CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu (24 h, rt) | <1% | 86% | <1% | 14% |

| CuBr/TEMPO/NMI (6 h, rt) | <1% | 64% | <1% | 36% |

| CuBr2/TEMPO/NMI (1 h, rt) | <1% | 94% | <1% | 6% |

|

| ||||

|

||||

| Pd(OAc)2/py (13 min, 80 °C) | 7% | 33%b | 14% | 46% |

| RuCl2(PPh3)3/TEMPO (7 h, 100 °C) | 44% | 39%b | <1% | 3% |

| CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu (24 h, rt) | 38% | 62%b | <1% | <1% |

| Cu(OTf)/TEMPO/NMI (24 h, rt) | <1% | 97%b | <1% | 2% |

|

|||||

| Pd(OAc)2/py (2 h, 80 °C) | 40% | 17% | 11% | 27% | 5% |

| RuCl2(PPh3)3/TEMPO (7 h, 100 °C) | 7% | 36% | 33% | 13% | 11% |

| CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu (24 h, rt) | 34% | 34% | 14% | <1% | 18% |

| Cu(OTf)/TEMPO/NMI (24 h, 50 °C) | 4% | 6% | 86% | 1% | 7% |

|

| |||||

|

|||||

| Pd(OAc)2/py (2 h, 80 °C) | <1% | <1% | 61% | 39% | |

| RuCl2(PPh3)3/TEMPO (7 h, 100 °C) | 7% | 26% | 67% | <1% | |

| CuBr2/TEMPO/KOtBu (24 h, rt) | 32% | 62% | 6% | <1% | |

| Cu(OTf)/TEMPO/NMI (3 h, 50 °C) | <1% | 4% | 96% | <1% | |

Diols 1-10 all underwent selective oxidation, undergoing nearly exclusive oxidation of 1° over 2° alcohols (Table 6). In some cases, however, the Cu(OTf)-based catalyst system is too active to achieve optimal selectivity, and improved results could be obtained with an alternate Cu source. For example, to obtain selective oxidation between the 1° and 2° benzylic positions of substrates 1 and 2, more selective oxidation was observed with a catalyst in which Cu(OTf) was replaced with the less active CuBr2. With substrate 1, undesired oxidation of the 2° position was further attenuated by using 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) in place of NMI, and the aldehyde product 11 could be obtained in very high selectivity and yield. With other substrates, no modification of the parent catalyst system was required. For example, oxidation of 1,5-hexanediol (4) with Cu(OTf)/TEMPO/NMI afforded selective oxidation at the primary position, followed by cyclization and further oxidation to yield the corresponding lactone 14. Lactonization with the Cu(OTf)/TEMPO/NMI system can also occur to form 7-membered lactones; however, the use of CuBr reduces lactonization and yields the linear aldehydes preferentially (13 and 17).

Table 6.

Selective Oxidation of Unprotected Diols using Cu/TEMPO/NMI.a

|

| |

|

| |

| 1° Benzylic vs 2° Benzylic | |

|

|

| 1° Aliphatic vs 2° Aliphatic | |

|

|

| 1° Benzylic vs 1° Aliphatic | |

|

|

| 1° Aliphatic vs 2° Benzylic | |

|

|

| Sterics | |

|

|

Isolated yields.

With DBU instead of NMI.

50 °C.

In a competition between a 1° benzylic and a 1° aliphatic alcohol, selective oxidation at the more activated benzylic position is observed (5 and 6 to yield 15 and 16, repectively). More challenging selectivities arise when an activated 2° benzylic alcohol and an unactivated 1° aliphatic alcohol are present within the same molecule (diols 7 and 8); however, selective oxidation of the 1° position of diol 8 can be achieved to yield lactone 18. In the absence of cyclization, (7 → 17), the (bpy)CuI(OTf)/TEMPO/NMI system is sufficiently active to oxidize both alcohols with little selectivity. Using a CuBr salt, however, provides a more selective catalyst that leads to preferential oxidation of the 1° alcohol. A similar benefit was observed in the competition between aliphatic 1° and 2° alcohols in the conversion of 3 to 13. Steric differentiation between two 1° aliphatic alcohols is also possible, as reflected by the selective oxidation of subsrates 9 and 10 into 19 and 20, respectively. With both of these substrates, the presence of an adjacent quaternary center enables selective oxidation of the less hindered alcohol.

These observations demonstrate that the activity of the (bpy)Cu/TEMPO catalyst system can be tuned to achieve highly selective oxidation of unprotected diols. The parent (bpy)CuI(OTf)/NMI catalyst appears to be the most active, giving high yields of aliphatic aldehydes and showing high steric selectivity. Replacement of OTf– with other non-coordinating counterions (BF4– or PF6–) has no impact on the catalyst activity. This catalyst, however, can effect oxidative lactonization and oxidation of 2° benzylic alcohols. The CuIBr/NMI pair is less active and more selective, affording aldehydes in high yields while minimizing the sequential oxidation of the substrate to form lactones (e.g., 7 → 17).33 The CuBr2 salt, in combination with NMI or DBU, is the least active and most selective, enabling control over the selectivity between 1° and 2° benzylic alcohols.

Conclusion

The present report highlights the development of a highly practical (bpy)CuI/TEMPO catalyst system for the selective oxidation of 1° alcohols to aldehydes. Several features of the catalyst system suggest that it is ideally suited for widespread use in synthetic chemistry. It is the first aerobic alcohol oxidation catalyst that exhibits high selectivity for primary alcohols and mediates efficient oxidation of aliphatic substrates. The methods are compatible with substrates bearing a variety of important functional groups, including heterocycles and other heteroatom-containing groups, as well as unprotected 2° alcohols. And, the methods exhibit a number of highly favorable practical characteristics: (1) ambient air can be used as the oxidant, (2) acetonitrile, a standard organic solvent, is the reaction medium and (3) all of the catalyst components (CuX salt, bpy, TEMPO, and NMI) are inexpensive, stable and commercially available reagents.

Experimental

General Considerations

1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 300 MHz or Varian Mercury 300 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in parts per million and referenced to the residual solvent signal;34 and all coupling constants are reported in Hz. High resolution mass spectra were obtained by the mass spectrometry facility at the University of Wisconsin. GC analyses were performed using a DB-Wax column installed in a Shimadzu GC-17A equipped with flame-ionization detector. Melting points were taken on a Mel-Temp II melting point apparatus. Column chromatography was performed on an Isco Combiflash system using Silicycle 60 silica gel.

The catalyst components and other commercially available reagents were obtained from Aldrich and used as received, unless otherwise noted. Most alcohols were obtained from commercial sources and used as received; however, diols were typically synthesized by reduction of the corresponding carboxylic acids with LiAlH4 in THF and purified by silica column chromatography (gradient elution of EtOAc in Hexanes). CH3CN was obtained from a solvent drying column present in the laboratory packed with activated molecular sieves; however, identical results were obtained with solvent used directly from commercial sources (e.g., Aldrich, HPLC grade). No precautions were taken to exclude air or water from the solvent or reaction mixtures. Reaction mixtures were monitored by TLC using KMnO4 as a staining agent.

Representative Procedure for the Oxidation of Primary Alcohols

To a solution of alcohol (1 mmol) in dry CH3CN (1 mL) in a 20 mm culture tube were added the following solutions: (1) [Cu(MeCN)4]X (X = OTf−, BF4−, or PF6−, 0.05 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN) (2) bpy (0.05 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN) (3) TEMPO (0.05 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN) (4) N-methyl imidazole (0.1 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN). The dark red/brown reaction mixture was stirred rapidly open to air and monitored by TLC until no starting material remained (often accompanied by a change in reaction color to green/blue). Preliminary studies indicate that the reactions described here are not subject to mass-transfer effects, and the rate of mixing and stir bar shape do not have a significant impact on the outcome of the reaction.

Larger scale reactions were run in over-sized round bottom flasks: (i) 10 mmol scale reactions were carried out with 50 mL of CH3CN in a 250 mL flask; (ii) 50 mmol scale reactions were carried out with 250 mL of CH3CN in a 1 L flask. Reactions to form volatile aldehydes were carried out in a round bottom flask fitted with a reflux condenser, a septum, and a balloon of house air (or O2).

Representative Procedure for the Selective Oxidation of Unprotected Diols

To a solution of alcohol (1 mmol) in dry CH3CN, (1 mL) in a 20 mm culture tube were added the following solutions: (1) Cu salt (0.05 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN) (2) bpy (0.05 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN) (3) TEMPO (0.05 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN) (4) base (0.1 mmol in 1 mL CH3CN). The reaction mixture was stirred rapidly open to air and monitored by TLC (see Table S3) until no starting material remained. The product was then worked up according to one of the following two methods (see SI for details):

Workup Method A

The reaction mixture was then neutralized with 1 N HCl and diluted with water (~10 mL) and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 20 mL). The combined organics were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by silica column chromatography (gradient elution of EtOAc in Hex).

Workup Method B

The crude reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by silica column chromatography (gradient elution of EtOAC in Hex).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Charles Alt (Eli Lilly) for performing HPLC analysis of the aldehyde product in Table 4, Entry 5. Financial support of this work was provided by the NIH (RC1-GM091161), the ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Postdoctoral Program in Environmental Chemistry. NMR spectroscopy facilities were partially supported by the NSF (CHE-9208463) and NIH (S10 RR08389).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Additional catalyst screening data, experimental details, and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).(a) Tojo G, Fernández M. Basic Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Springer; New York: 2010. Oxidation of Alcohols to Aldehydes and Ketones. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tojo G, Fernández M. Basic Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Spriner; New York: 2010. Oxidation of Primary Alcohols to Carboxylic Acids. [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Bowden K, Heilbron IM, Jones ERH, Weedon BC. J. Chem. Soc. 1946:39–45. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Suggs JW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:2647–2650. [Google Scholar]; (c) Piancatelli G, Scettri A, D’Auria M. Synthesis. 1982:245–258. [Google Scholar]; (d) De A. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 1982;41:484–494. [Google Scholar]; (e) Luzzio FA, Guziec FS. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1988;20:533–584. [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Ladbury JW, Cullis CF. Chem Rev. 1958;58:403–438. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fatiadi AJ. Synthesis. 1976:65–104. [Google Scholar]; (c) Taylor RJK, Reid M, Foot J, Raw SA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:851–869. doi: 10.1021/ar050113t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Pfitzner KE, Moffatt JG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:3027–3028. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mancuso AJ, Huang S-L, Swern D. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:2480–2482. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mancuso AJ, Brownfain DS, Swern D. J. Org. Chem. 1979;44:4148–4150. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tidwell TT. Synthesis. 1990:857–870. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Dess DB, Martin JC. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:4155–4156. [Google Scholar]; (b) Frigerio M, Santagostino M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:8019–8022. [Google Scholar]; (c) Uyanik M, Ishihara K. Chem. Commun. 2009:2086–2099. doi: 10.1039/b823399c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Parikh JR, Doering W. v. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:5505–5507. [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Anelli PL, Biffi C, Montanari F, Quici S. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:2559–2562. [Google Scholar]; (b) de Nooy AEJ, Besemer AC, van Bekkum H. Synthesis. 1996:1153–1176. [Google Scholar]; (c) De SMVN. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2006;3:155–165. [Google Scholar]; (d) Vogler T, Studer A. Synthesis. 2008:1979–1993. [Google Scholar]; (e) Ciriminna R, Pagliaro M. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2010;14:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Caron S, Dugger RW, Ruggeri S,G, Ragan JA, Ripin DHB. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2943–2989. doi: 10.1021/cr040679f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Constable DJ, Dunn PJ, Hayler JD, Humphrey GR, Leazer JL, Linderman RJ, Lorenz K, Manley J, Pearlman BA, Wells A, Zaks A, Zhang TY. Green Chem. 2007;9:411–420. [Google Scholar]; (c) Alfonsi K, Colberg J, Dunn PJ, Fevig T, Jennings S, Johnson TA, Kleine HP, Knight C, Nagy MA, Perry DA, Stefaniak M. Green Chem. 2008;10:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- (9).For reviews, see: Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. In: Modern Oxidation Methods. Bäckvall J-E, editor. Wiley-VCH Verlag Gmb & Co.; Weinheim: 2004. pp. 83–118. Sheldon RA, Arends IWCE, ten Brink G-J, Dijksman A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002;35:774–781. doi: 10.1021/ar010075n. Zhan B-Z, Thompson A. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:2917–2935. Mallat T, Baiker A. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3037–3058. doi: 10.1021/cr0200116. Markó IE, Giles PR, Tsukazaki M, Chellé-Regnaut I, Gautier A, Dumeunier R, Philippart F, Doda K, Mutonkole J-L, Brown SM, Urch CJ. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2004;56:211–240. Schultz MJ, Sigman MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8227–8241.

- (10).(a) Mueller JA, Goller CP, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9724–9734. doi: 10.1021/ja047794s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dijksman A, Marino-González A, Payeras AM, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6826–6833. doi: 10.1021/ja0103804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).A versatile organocatalytic aerobic oxidation method was reported recently using 5-Fluoro-2-azaadamantane-N-oxyl (F-AZADO) or the corresponding oxammonium nitrate salt as the catalyst. These reactions exhibit broad scope, including 1° and 2° allylic, benzylic and aliphatic substrates. The reactions were performed with an air balloon in acetic acid as the solvent. This catalyst is not yet available commercially, however the parent AZADO species can be obtained from Aldrich (250 mg, $219). For leading references, see: Shibuya M, Osada Y, Sasano Y, Tomizawa M, Iwabuchi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6497–6500. doi: 10.1021/ja110940c. Shibuya M, Tomizawa M, Suzuki I, Iwabuchi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8412–8413. doi: 10.1021/ja0620336.

- (12).For reviews, see ref. 9 and the following: Gligorich KM, Sigman MS. Chem. Commun. 2009:3854–3867. doi: 10.1039/b902868d. Stahl SS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3400–3420. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300630.

- (13).For leading references, see: Nishimura T, Onoue T, Ohe K, Uemura S. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:6750–6755. doi: 10.1021/jo9906734. Schultz MJ, Park CC, Sigman MS. Chem. Commun. 2002:3034–3035. doi: 10.1039/b209344h. ten Brink G-J, Arends IWCE, Hoogenraad M, Verspui G, Sheldon RA. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003;345:1341–1352. Mueller JA, Goller CP, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9724–9734. doi: 10.1021/ja047794s. Schultz MJ, Hamilton SS, Jensen DR, Sigman MS. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3343–3352. doi: 10.1021/jo0482211. Bailie DS, Clendenning GMA, McNamee L, Muldoon MJ. Chem. Commun. 2010:7238–7240. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01138j.

- (14).For leading references, see: Lenz R, Ley SV. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1997:3291–3292. Dijksman A, Marino-González AM, Payeras M, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6826–6833. doi: 10.1021/ja0103804. Hasan M, Musawir M, Davey PN, Kozhevnikov IV. J. Mol. Catal. A. 2002;180:77–84. Mizuno N, Yamaguchi K. Catal. Today. 2008;132:18–26.

- (15).(a) Nishimura T, Kakiuchi N, Onoue T, Ohe K, Uemura S. J. Chem. Soc., Perking Trans. 1. 2000:1915–1918. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mifsud M, Parkhomenko KV, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:1040–1044. [Google Scholar]

- (16).For leading references, see: Steinhoff BA, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11268–11278. doi: 10.1021/ja049962m. Steinhoff BA, King AE, Stahl SS. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:1861–1868. doi: 10.1021/jo052192s. Steinhoff BA, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4348–4355. doi: 10.1021/ja057914b.

- (17).Ye X, Johnson MD, Diao T, Yates MH, Stahl SS. Green Chem. 2010;12:1180–1186. doi: 10.1039/c0gc00106f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cu/TEMPO catalyst systems: Semmelhack MF, Schmid CR, Cortés DA, Chou CS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:3374–3376. Ragagnin G, Betzemeier B, Quici S, Knochel P. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:3985–3991. Geisslmeir D, Jary WG, Falk H. Monatsh. Chem. 2005;136:1591–1599. Jiang N, Ragauskas AJ. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:7087–7090. doi: 10.1021/jo060837y. Mannam S, Alamsetti SK, Sekar G. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:2253–2258. Figiel PJ, Sibaouih A, Ahmad JU, Nieger M, Räisänen MT, Leskelä M, Repo T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:2625–2632.

- (19).Copper/dialkylazodicarboxylate catalyst systems: See ref. 9e for a review and the following primary references: Markó IE, Giles PR, Tsukazaki M, Brown SM, Urch CJ. Science. 1996;274:2044–2046. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2044. Markó IE, Gautier A, Mutonkole J-L, Dumeunier R, Ates A, Urch CJ, Brown SM. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001;624:344–347. Markó IE, Gautier A, Dumeunier R, Doda K, Philippart F, Brown SM, Urch CJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:1588–1591. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353458.

- (20).Iwahama T, Yoshino Y, Keitoku T, Sakaguchi S, Ishii Y. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:6502–6507. doi: 10.1021/jo000760s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Martín SE, Suárez DF. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4475–4479. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yin W, Chu C, Lu Q, Tao J, Liang X, Liu R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:113–118. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang N, Liu R, Chen J, Liang X. Chem. Commun. 2005:5322–5324. doi: 10.1039/b509167e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a) Maeda Y, Kakiuchi N, Matsumura S, Nishimura T, Kawamura T, Uemura S. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:6718–6724. doi: 10.1021/jo025918i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hanson SK, Wu R, Silks LA. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1908–1911. doi: 10.1021/ol103107v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).The present study targets catalysts with utility in synthetic organic chemistry. A number of catalyst systems for alcohol oxidation have been developed that are functional mimics of galactose oxidase, a Cu-containing enzyme that mediate primary alcohol oxidation. These catalysts are important from a mechanistic perspective, specifically their use of Cu in combination with a ligand-based radical to effect two-electron alcohol oxidation, but they typically exhibit rather narrow synthetic scope. For leading references, see: Wang YD, DuBois JL, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Stack TDP. Science. 1998;279:537–540. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.537. Chaudhuri P, Hess M, Flörke U, Wieghardt K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:2217–2220. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2217::AID-ANIE2217>3.0.CO;2-D. Chaudhuri P, Hess M, Muller J, Hildenbrand K, Bill E, Weyhermuller T, Wieghardt K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9599–9610.

- (24).(a) Gamez P, Arends IWCE, Reedijk J, Sheldon RA. Chem. Commun. 2003:2414–2415. doi: 10.1039/b308668b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gamez P, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA, Reedijk J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:805–811. [Google Scholar]

- (25).The mechanisms of these reactions are not well understood; however, recent studies suggest the selectivity for 1° over 2° alcohols reflects a Cu/TEMPO-based oxidant that differs from the free oxammonium species that is the active oxidant in the NaOCl/TEMPO system, for example (see ref. 7). For mechanistic considerations, see the following reports: Dijksman A, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1:3232–3237. doi: 10.1039/b305941c. Michel C, Belanzoni P, Gamez P, Reedijk J, Baerends EJ. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:11909–11920. doi: 10.1021/ic902155m. Kumpulainen ETT, Koskinen AMP. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009;15:10901–10911. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901245.

- (26).Somewhat increased reaction rates can also be achieved by using a more electron-rich bpy ligand, as noted by Sheldon and coworkers (see ref. 24b). For example, in the oxidation of N-Boc-prolinol, the yield increased from 67% to 80% upon replacing the parent bpy ligand with 4,4′-dimethoxy-2,2′-bipyridine [(MeO)2bpy] under standard reaction conditions (ambient temperature, 24 h).

- (27).When (Z)-4-benzyloxy-but-2-enol (cf. Table 4, entry 4) was oxidized under Swern conditions, extensive alkene isomerization was observed (cis:trans 1:8), consistent with literature reports: Clarke PA, Rolla GA, Cridland AP, Gill AA. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:9124–9128.

- (28).Aterburn JB. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9765–9788. [Google Scholar]

- (29).For efforts to achieve selectivity with catalytic aerobic oxidation methods, see: Mizoguchi H, Uchida T, Ishida K, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:3432–3435. Painter RM, Pearson DM, Waymouth RM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:9456–9459. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004063.

- (30).Romeo A, Maione AM. Synthesis. 1984;11:955–957. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tomioka H, Takai K, Oshima K, Nozaki H. Tetreahedron Lett. 1981;22:1605–1608. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Doyle MP, Dow RL, Bagheri V, Patrie WJ. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:476–480. [Google Scholar]

- (33).The mechanistic origin of catalyst-controlled selectivity in these cases is not clear; however, time courses of the reactions of substrate 7 show that the lactol intermediate undergoes further oxidation to the lactone more readily with the Cu(OTf)-based catalyst system.

- (34).Gottlieb HE, Kotlyar V, Nudelman A. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7512–7515. doi: 10.1021/jo971176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.