Abstract

Bacterial O-SP–core antigens can be conjugated to proteins in the same, simple way as synthetic, linker-equipped carbohydrates by applying squaric acid chemistry. Introduction of spacers (linkers) to either O-SP–core antigens or protein carriers, which is involved in commonly applied protocols, is not required. The newly developed method here described consists of preparation of a squaric acid monoester derivative of O-SP–core antigen, utilizing the amino group inherent in the core, and reaction of the monoester with the carrier protein. The intermediate monoester can be easily purified, its conjugation can be monitored by SELDI-TOF mass spectrometry and, thus, readily controlled, since the conjugation can be terminated when the desired carbohydrate–protein ratio is reached. Here we describe production of conjugates containing the O-SP-core antigen of Vibrio cholerae O1, the major cause of cholera, a severe dehydrating diarrheal disease of humans. The resultant products are recognized by convalescent phase sera from patients recovering from cholera in Bangladesh, and anti-O-SP-core-protein responses correlate with plasma anti-lipopolysaccharide and vibriocidal responses, which are the primary markers of protection from cholera. The results suggest that such conjugates have potential as vaccines for cholera and other bacterial diseases.

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are carbohydrate polymers characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria. They consist of Lipid A, the toxic part through which the LPS is anchored into the bacterial cell wall, the intermediate core oligosaccharide, and the O-specific polysaccharide (O-antigen, O-SP), which extends into the bacterial environment, and is a virulence factor and the major protective antigen of V. cholerae and many other bacterial pathogens1–3. Because of their toxicity, complete LPS molecules are normally not used as components of vaccines, especially parenteral vaccines, although oral whole-organism killed vaccines contain a large component of LPS. Lipopolysaccharides can be detoxified in many ways, one of which is mild hydrolysis with dilute acetic acid, which separates the O-SP–core antigen from the Lipid A. Many methods for conjugation of carbohydrates, synthetic or bacterial, to proteins are available4–6, but most of them rely on significant chemical modification of the carbohydrate antigen to make it amenable to conjugation. Such approaches have the potential disadvantage that many epitopes in the antigen important for eliciting protective immunity may be changed by the treatment. This problem can be overcome by using for conjugation a functional group intrinsic to the polysaccharide, such as a carboxyl group in acidic polysaccharides or the free amino group in glucosamine that is present in the O-SP–core. A number of groups have produced conjugate vaccines targeting the O-SP of Vibrio cholerae, a Gram-negative bacterium and the cause of cholera, a severe dehydrating diarrheal illness of humans with epidemic potential7. Globally, almost all cholera is caused by organisms of two serotypes (Inaba and Ogawa) of theV. cholerae O1 serogroup. Protection against cholera is serogroup specific, and the vibriocidal response and anti-LPS antibodies are currently among the best markers of protection against cholera8. The vibriocidal response itself is largely directed against V. cholerae LPS9, 10.

The first to attempt conjugation of an acid-detoxified V. cholerae LPS to proteins utilizing the amino group in the core were Gupta and coworkers11. They derivatized the O-SP–core antigen of V. cholerae O1 (serotype Inaba, Fig. 1), as well as the carrier protein, with N-succinimidyl 3-(2-pyridyldithio) propionate, and effected single-point attachment between the two molecular species. A similar approach, but using different chemistry, was taken by Mulard and coworkers 12 in their more recent, very carefully executed work. When the latter authors12 revisited the approach by Gupta11, which involved derivatization of both carrier and antigen, they argued that introduction of linker was necessary to overcome the decreased reactivity of the amino group in the glucosamine, due to steric hindrance.

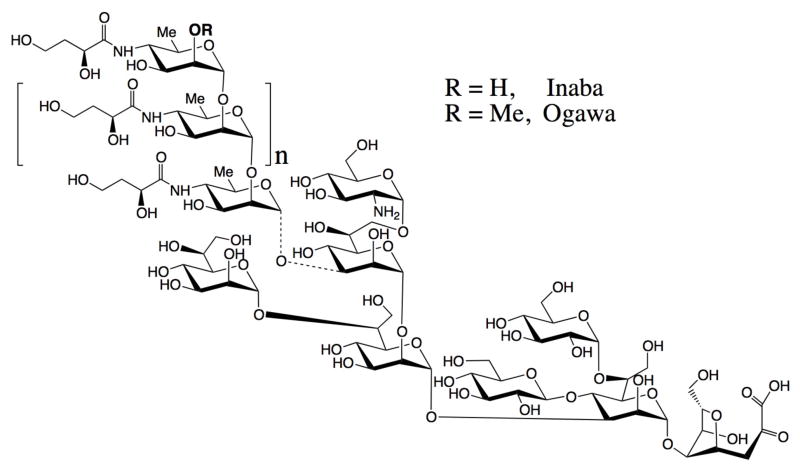

Fig. 1.

Structure of bacterial O-SP–core antigen of Vibrio cholerae O1, serotype Inaba and Ogawa. The dotted bond indicates that the linkage of the O-SP to core has not been established.

The squaric acid chemistry of conjugation of two amine species discovered by Tietze13 has been shown to be a useful means for preparation of neoglycoconjugates from synthetic oligosaccharides14. The method is quite efficient6, but reservations have been expressed concerning its potential utility in conjugate vaccine development15. For instance, in limited animal studies, oligosaccharides linked to proteins via squaric acid chemistry induced lower anti-oligosaccharide antibody responses compared to responses induced by an oligosaccharide-protein conjugate linked via adipic acid chemistry, although both vaccines induced very prominent anti-oligosaccharide responses16. We have previously developed prototype cholera vaccines using short synthetic oligosaccharides involving the terminal sugar of V. cholerae O1 O-SP and squaric acid chemistry, and found these constructs to be immunogenic and protective in the standard cholera animal model17, calling into question the assumption that conjugation by squaric acid chemistry may not be of utility. We have examined a number of variables that affect the rate of conjugation by the squaric acid method18. Based on our more recent detailed study19, we have revised the original protocol and have now applied it to the full bacterial O-SP–core antigens of V. cholerae O1 Ogawa and Inaba, not just small oligosaccharide fragments, and a model protein BSA directly, without prior introduction of a linker to either O-SP–core antigen or protein carrier. Here, we report that such conjugation is not only possible, but equally simple as with synthetic, linker-equipped oligosaccharides and, as with synthetic oligosaccharides14, can be done with a very small amount of material. The method in the present form19 is simple to perform, gives reproducible results, allows preparation of carbohydrate–protein constructs in a predictable way, and appears to be superior to protocols developed earlier.

Experimental procedures

General

V Vials equipped with Spin Vanes (Wheaton Science) were used as reaction vessels. Conjugation of carbohydrates was monitored by the BioRad Protein Chip SELDI system using NP-20 chip arrays. 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (sinapinic acid) was used as matrix. 13C NMR spectra (150 MHz) of O-SP–core antigens were taken at ambient temperature for solutions in D2O with a Bruker Avance 600 spectrometer equipped with a cryoprobe. Assignments of NMR signals could be confidently made by comparison with spectra of synthetic20 α-glycosides of hexasaccharide fragments of the respective O-SPs, since spectra of the O-SP–core and the hexasaccharides showed close similarity of chemical shifts of equivalent carbon atoms of the internal residues and of the terminal upstream21 residues. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from Sigma (Cat. No. A-4503), and used as supplied. Squaric acid dimethyl ester was purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company and recrystallized from MeOH.

Isolation of the lipopolysaccharides of Vibrio cholerae O1, serotypes Inaba and Ogawa, and preparation of the O-SP–core antigens

LPS was obtained from V. cholerae O1, Ogawa (strain X-25049) or Inaba (strain 19479), by hot phenol/water extraction22 followed by enzymatic treatment (DNase, RNase and protease), and ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 3 h). The pellet containing LPS was dialyzed against distilled water and freeze-dried. The LPS [10 mg/mL in 1% (v/v) aqueous acetic acid] was heated at 105°C for 3 h23. Each hydrolysate was separated into chloroform-soluble and water-soluble fractions by thorough mixing with an equal volume of chloroform, followed by low-speed centrifugation. The water-soluble fraction containing the degraded polysaccharide moiety was separated, washed three or more times with chloroform, and then freeze-dried. The degraded polysaccharide was further fractionated by size exclusion chromatography (Sephacryl S-200) using water as eluant, giving two major peaks. The first peak corresponding to the O-SP-core23, 24 was isolated and freeze-dried. The crude O-SP–core products were further purified by ultrafiltration using centrifugal filter devices (3K Amicon Ultra, Millipore) and dialyzed against 10 mM aqueous ammonium carbonate (centrifugation at 4°C, 14,000 × g, 8 times, ~35 min each time) to remove the low molecular mass material. The retentate was lyophilized to afford the O-SP–core antigens as white solids. The 13C NMR spectra are in Fig. 2. The SELDI-TOF mass spectral analysis indicated that the average molecular mass of the Inaba and Ogawa O-SP–core antigens were ~5,100 and 5,900 Da, respectively.

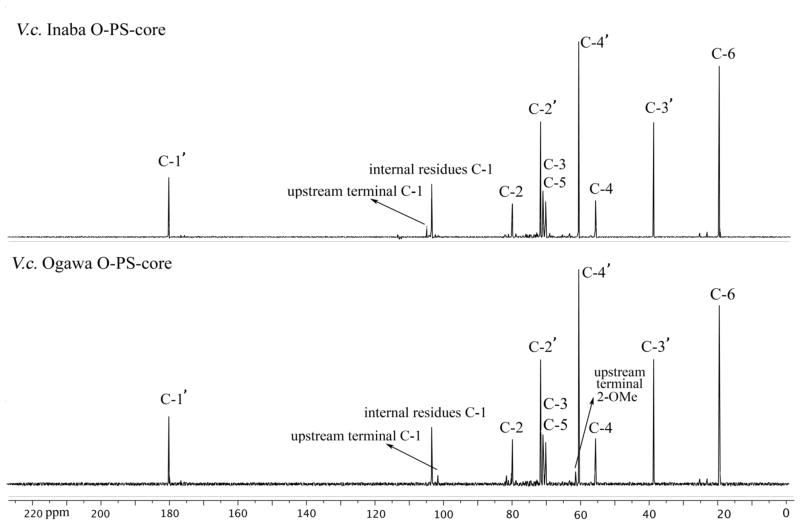

Fig. 2.

13C NMR spectra of the crude O-SP–core antigens of V. cholerae, serotype Inaba and Ogawa in D2O.

Preparation of squarate derivatives of the O-SP–core antigens

3,4-Dimethoxy-3-cyclobutene-1,2-dione (~0.5 mg) was added to a solution of O-SP-core antigen (0.80 mg and 0.92 mg for Inaba and Ogawa, respectively) in pH 7 phosphate buffer (0.05 M, 50 μL) contained in a 1 mL V shaped reaction vessel, and the mixture was gently stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The resulting solution was transferred into an Amicon Ultra (0.5 mL, 3K cutoff) centrifuge tube and dialyzed against pure water (centrifugation at 4°C, 14,000 × g, 8 times, ~35 min each time). The retentate was lyophilized to afford the O-SP-core squarate monomethyl ester as white solid [0.75 mg (94 %) and 0.86 mg (93 %)] for Inaba and Ogawa, respectively.

Conjugation of the O-SP–core antigens to BSA

Conjugation of the Inaba O-SP–core antigen

BSA (0.9 mg) and the methyl squarate derivative of the Inaba O-SP–core antigen described above (0.75 mg) were weighed into a 1 mL V shape reaction vessel and 60 μL of 0.5 M pH 9 borate buffer was added (to form ~2.5 mM solution with respect to the antigen; antigen: carrier = 10.8: 1). A clear solution was formed. The mixture was stirred at room temperature and the reaction was monitored by SELDI-TOF MS at 24, 48, 72, 96 and 240 h (Fig. 3), when the reaction was terminated by addition of 300 μL of pH 7 phosphate buffer. The solution was transferred into an Amicon Ultra (0.5 mL, 30 K cutoff) centrifuge tube and dialyzed (centrifugation at 4°C, 10,000 × g, 8 times, 12 min) against 10 mM aqueous ammonium carbonate. After lyophilization, 0.80 mg (73%, based on BSA) of conjugate was obtained as a white solid. Based on the average MW of the hapten, the ratio of hapten:BSA was 2.8:1 (conjugation efficiency, 26%).

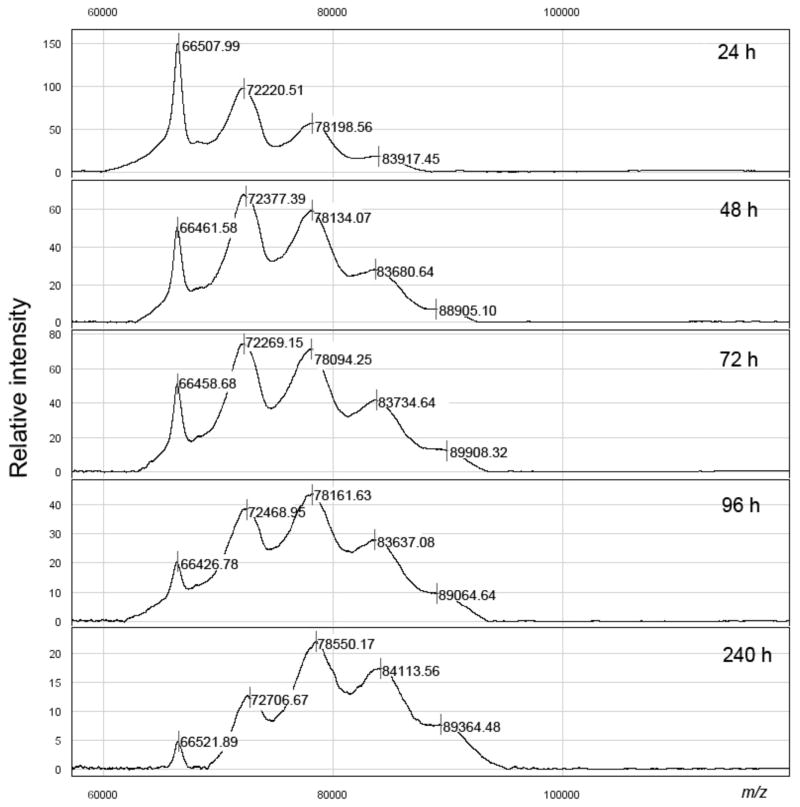

Fig. 3.

Monitoring of the conjugation of Inaba O-SP–core antigens to BSA.

Conjugation of the Ogawa O-SP–core antigen

The protocol described above was followed with 0.86 mg of the methyl squarate derivative of the Ogawa antigen described above, 0.45 mg of BSA (antigen: carrier = 21.5: 1) and 30 μL of pH 9 borate buffer (~4.9 mM solution with respect to hapten). Monitoring of the progress of the conjugation is shown in Fig. 4. After freeze-drying, 0.54 mg (84%, based on BSA) of conjugate was obtained as a white solid. Based on the average MW of the hapten, the ratio of hapten: BSA was 4.8:1 (conjugation efficiency, 23%).

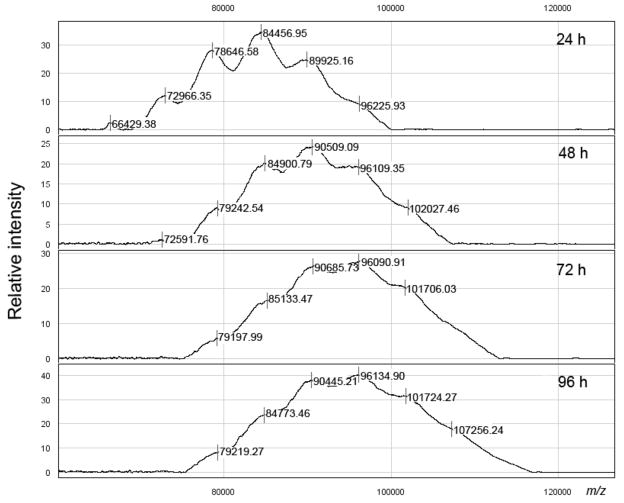

Fig. 4.

Monitoring of the conjugation of Ogawa O-SP–core antigens to BSA.

Evaluation of immuno-reactivity of conjugates

Assessing lipopolysaccharide (LPS), O-SP-core-BSA and BSA-specific antibody responses in plasma of patients with cholera, as well as vibriocidal responses

Acute and convalescent phase blood was obtained through fully Institutional Review Board-approved protocols from twenty individuals with V. cholerae O1 stool-culture-confirmed cholera (Ogawa=10; Inaba=10) admitted to the hospital of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, in Dhaka Bangladesh (ICDDR, B). For this study, we used blood samples obtained on days 2 and 7 after onset of illness for antigen-specific and vibriocidal assays. We measured the vibriocidal antibody titer and antigen-specific IgG antibody responses using the homologous serotype of V. cholerae O1 LPS, or O-SP-core-BSA, Ogawa or Inaba.

We quantified anti-LPS, O-SP-core-BSA and BSA IgG responses in plasma using standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocols25, 26. To assess anti-LPS IgG responses, we coated ELISA plates with the homologous serotype of V. cholerae O1 LPS (2.5 μg/mL)27 in PBS. To assess anti-O-SP–core-BSA or anti-BSA IgG responses, we coated ELISA plates with O-SP–core/BSA (1 μg/mL) or BSA (5 μg/mL) in carbonate buffer pH 9.6, respectively. To each well, we added 100 μL/well of plasma (diluted 1:50 in 0.1% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline–Tween), and detected the presence of antigen-specific antibodies using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG antibody. After 1.5 h incubation at 37°C, we developed the plates with a 0.55 mg/mL solution of 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS; Sigma) with 0.03% H2O2 (Sigma), and determined the optical density at 405 nm with a Vmax microplate kinetic reader (Molecular Devices Corp. Sunnyvale, CA). Plates were read for 5 min at 14 s intervals, and the maximum slope for an optical density change of 0.2 U was reported as millioptical density units per minute (mOD/min). We normalized ELISA units by calculating the ratio of the optical density of the test sample to that of a standard of pooled convalescent-phase plasma from patients recovered from cholera. We assessed vibriocidal responses as previously described, using guinea pig complement and the homologous serotype of V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (X-25049) or Inaba (19479) as the target organism25. The vibriocidal titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution resulting in >50% reduction of the optical density associated with V. cholerae growth compared to that of the positive control wells without plasma26. We compared the magnitude of acute to convalescent phase responses, and tested for significance using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, and used linear regression for correlation analysis between vibriocidal antibody and antigen-specific antibody responses. All reported P values were two-tailed, with a cutoff of P < 0.05 considered a threshold for statistical significance.

Results and Discussion

Conjugations were performed with O-SP–core antigens of Vibrio cholerae O1, serotypes Inaba and Ogawa, and the increasing molecular mass of the conjugate was monitored as described28. The structures of O-SPs of the two strains are very similar; they consist of a chain of (1→2)-α-linked moieties of 4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-α-D-mannopyranose (perosamine), the amino groups of which are acylated with 3-deoxy-L-glycero-tetronic acid. The O-SPs of the two strains differ in that the terminal, upstream perosamine moiety in the Ogawa strain carries a methoxy group at C-2 (Fig. 1). The 13C NMR spectra (Fig. 2) of the antigens, where the signals of the O-SPs largely predominate, show all structurally significant peaks present in the spectra of the related, synthetic hexasaccharides20.

To ascertain whether simple, direct conjugation of O-PS–core antigens is feasible, the antigens were treated with excess of squaric acid dimethyl ester at pH 7 for 2 days, when the product was isolated by dialysis followed by freeze-drying. The material thus obtained showed only moderate UV absorption at the wavelength characteristic of squaric acid, but successful formation of the corresponding monomethyl ester manifested itself when the material was treated with BSA at pH 9 resulting in smooth conjugate formation (Fig. 3 and 4).

Knowing that the reaction rate of conjugation decreases with the size of oligosacchrides, and considering the actual reaction rates for a disaccharide, tetrasaccharide and a hexasaccharide19, the conjugation was carried out at initial Inaba O-SP–core/BSA ratio 1: 1.2 (w/w), which corresponded to an approximate molar Inaba O-SP–core/BSA ratio of 10.8/1. The conjugation was performed at an O-SP–core concentration of ~2.5 mM. When the conjugation process was terminated after 10 d, SELDI analysis of the purified conjugate after freeze drying showed that the average molecular mass of the conjugate obtained was 81,000 Da (molar ratio O-SP–core: BSA = ~2.8). The conjugate still contained some (~5%) of the unchanged BSA (shown also in Fig. 3, 240 h).

To ensure that no BSA used at the onset of the conjugation would be left unconjugated, the reaction of the Ogawa O-SP–core antigen was set up at a higher initial O-SP–core: BSA ratio [~2: 1 (w/w), which corresponded to an approximate initial molar Ogawa O-SP–core/BSA ratio of 21.5: 1]. As shown in Fig. 4, only a negligible amount of unchanged BSA was present in the conjugation mixture after 24 h of the reaction time. After 96 h, when the conjugation was terminated, the conjugate was isolated, and MS analysis by SELDI showed the average molecular mass of the conjugate obtained to be ~95,000 Da (molar ratio O-SP–core: BSA = ~4.8).

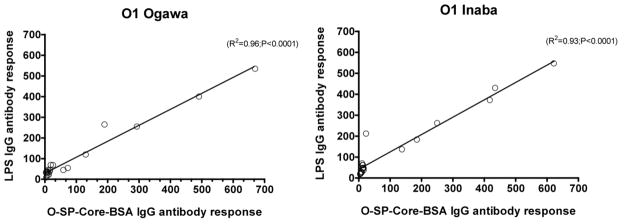

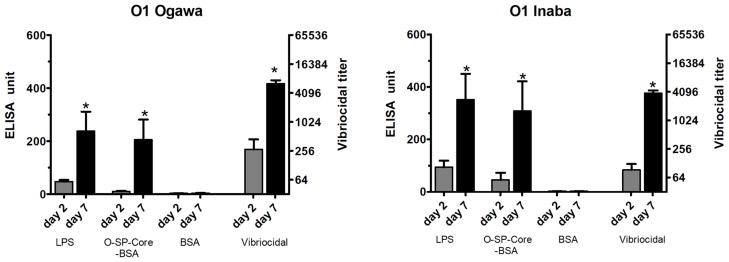

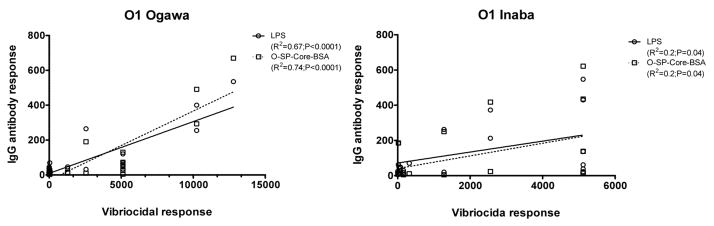

To assess the immunoreactivity of the conjugates and their potential use as cholera vaccines, we measured anti-O-SP-core-BSA antibody levels in the blood of patients with cholera in Bangladesh, and compared these responses to anti-LPS and vibriocidal responses, the latter two being among the primary predictors of protection against cholera8, 29–31. There was excellent correlation of the immunoreactivity of the O-SP–core–BSA conjugates and the homologous anti-LPS responses in convalescent phase blood of humans recovering from cholera in Bangladesh (Ogawa, R2 =0.96, P<0.001; Inaba, R2 =0.93, P<0.001; Fig 5). There was also significant and antigen-specific increases in anti-O-SP–core–BSA responses in convalescent compared to acute phase blood for both the Ogawa and Inaba constructs (P<0.05; Fig. 6). Responses correlated with the vibriocidal response for Ogawa, and less well for Inaba (Ogawa, R2 =0.74, P<0.001; Inaba, R2 =0.2, P<0.04; Fig. 7); importantly these correlation curves mirrored those of the LPS IgG to vibriocidal relationship.

Fig. 5.

Correlation between anti-V. cholerae O1 LPS IgG antibody responses and corresponding O-SP–core–BSA IgG antibody responses. Lines designate the linear correlations between the responses. Antibody responses were assessed for 10 patients with Ogawa (left panel) and 10 with Inaba (right panel) during the acute and convalescent phases of infection.

Fig. 6.

Mean normalized antigen-specific IgG and vibriocidal antibody responses in plasma (with standard errors of the means [SEM]). Plasma IgG and vibriocidal responses are shown on the left and right (log 2) axes, respectively. An asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference (P<0.05) from the baseline (day 2) titer.

Fig. 7.

Correlation between vibriocidal antibody responses and the corresponding LPS or O-SP–core-BSA IgG antibody responses. Lines designate the linear correlations between the responses. Ogawa and Inaba refer to serotype of V. cholerae used in vibriocidal assay.

As pointed out above, previous researchers have proposed that conjugate vaccines using squaric acid chemistry may not permit the development of maximal immune responses targeting sugar moieties. Here we show that O-SP–core-protein conjugates produced by this simplified protocol are recognized by convalescent phase sera from patients recovering from cholera in Bangladesh, and anti-O-SP-core-protein responses correlate with plasma anti-LPS and vibriocidal responses. These results suggest that such conjugates might have utility as vaccines, although this can only be addressed by direct immunization studies and immunologic analysis. Currently available cholera vaccines use the oral route of immunization with killed whole cell preparations, require repetitive dosing, and provide protection that lasts for six to 36 months32. Infection with natural cholera results in protection that lasts for years or decades33–35. Development of inexpensive and simple-to-produce cholera vaccines that provide durable protective immunity would be significant. Whether a conjugate vaccine administered parenterally, transcutaneously, singly, or as booster would fulfill these parameters is currently unclear and will be the objective of our future investigations.

Conclusions

We have shown that when a sufficiently powerful method of conjugation is applied, coupling of bacterial O-SP–core antigens to proteins is a simple, high yielding process, and derivatization aimed at introducing linkers to either O-SP–core antigens or carrier proteins prior to conjugation is not necessary. This could eliminate lengthy and often costly operations involved in industrial conjugate production. Squaric acid chemistry of conjugation of amine-containing substances13, 19 is a useful tool for conjugation of carbohydrate antigens, synthetic or bacterial, to amine containing carriers. As can be expected from reaction rates determined for various oligosaccharides by this method19, high molecular mass substances, such as the fragments of LPS used in this work, conjugate at a proportionally diminished, but acceptable, rate and efficiency. Conjugation of O-SP–core antigens to protein carriers by this method utilizes the free amino group that is inherent in the LPS core and, thus, yields neoglycoconjugates with single-point attachment of ligands to carriers. From this point of view, the method is analogous to those involving chemical attachment of spacers to the synthons involved prior to conjugation11, 12. Compared to the latter approaches, the conjugation described herein is much simpler and less laborious, and affords conjugates in higher yields with comparable overall conjugation efficiency. It produces conjugates that are fully and specifically recognized by immune responses in humans recovering from infection. Such features are particularly attractive for development of conjugate vaccines such as cholera, targeting infections of the world’s most impoverished.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDDK, as well the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Dhaka, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B), and NIAID AI077883 (ETR), AI058935 (SBC, FQ), AI089721 (RCC), and the Fogarty International Center (FIC) TW05572 (MMA, FQ).

References

- 1.Manning PA, Stroeher UH, Morona R. Molecular basis for O-antigen biosynthesis in Vibrio cholerae O:1 Ogawa-Inaba switching. In: Wachsmuth IK, Blake PA, Olsvik O, editors. Vibrio cholerae and Cholera: Molecular to Global Perspectives. Chapter 6. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, D.C: 1994. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passwell JH, Harlev E, Ashkenazi S, Chu C, Miron D, Ramon R, Farzan N, Shiloach J, Bryla DA, Majadly F, Roberson R, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. Safety and immunogenicity of improved Shigella O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines in adults in Israel. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69:1351–1357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1351-1357.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Szu SC, Pozsgay V. Bacterial polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines. Pure Appl Chem. 1999;71:745–754. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. Academic Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dick WE, Jr, Beurret M. Glycoconjugates of bacterial carbohydrate antigens. In: Cruse JM, Lewis RE Jr, editors. Conjugate Vaccines. Krager; Basel: 1989. pp. 48–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundle DR. New Frontiers in the Chemistry of Glycoconjugate Vaccines. In: Bagnoli RRaF., editor. Vaccine Design: Innovative Approaches and Novel Strategies. Caister Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan ET. The cholera pandemic, still with us after half a century: time to rethink. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramamurthy T, Garg S, Sharma R, Bhattacharya SK, Nair GB, Shimada T, Takeda T, Kurazano H, Pal A. Emergence of novel strain of Vibrio cholerae with epidemic potential in southern and eastern India. Lancet. 1993;341:703–704. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90480-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majumdar AS, Dutta P, Dutta D, Ghose AC. Antibacterial and antitoxin responses in the serum and milk of cholera patients. Infect Immun. 1981;32:1–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.1.1-8.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svennerholm AM. Experimental studies on cholera immunization. 4 The antibody response to formalinized Vibrio cholerae and purified endotoxin with special reference to protective capacity. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1975;49:434–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta RK, Szu SC, Finkelstein RA, Robbins JB. Synthesis, Characterization and some immunochemical properties of conjugates composed of the detoxified lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1 serotype Inaba bound to cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3201–3208. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3201-3208.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grandjean C, Boutonnier A, Dassy B, Fournier JM, Mulard LA. Investigation towards bivalent chemically defined glycoconjugateimmunogens prepared from acid-detoxified lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1, serotype Inaba. Glycoconjugate J. 2009;26:41–55. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tietze LF, Schröter C, Gabius S, Brinck U, Goerlach-Graw A, Gabius HJ. Conjugation of p-aminophenyl glycosides with squaric acid diester to a carrier protein and the use of neoglycoprotein in the histochemical detection of lectins. Bioconjugate Chem. 1991;2:148–153. doi: 10.1021/bc00009a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamath VP, Diedrich P, Hindsgaul O. Use of diethyl squarate for the coupling of oligosaccharide amines to carrier proteins and characterization of the resulting neoglycoproteins by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Glycoconjugate J. 1996;13:315–319. doi: 10.1007/BF00731506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, Ling CC, Bundle DR. A New Homobifunctional p-Nitro Phenyl Ester Coupling Reagent for the Preparation of Neoglycoproteins. Organic Letters. 2004;6:4407–4410. doi: 10.1021/ol048614m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mawas F, Niggemann J, Jones C, Corbel MJ, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG. Immunogenicity in a Mouse Model of a Conjugate Vaccine Made with a Synthetic Single Repeating Unit of Type 14 Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Coupled to CRM197. Infection and Immunity. 2002:5107–5114. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5107-5114.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chernyak A, Kondo S, Wade TK, Meeks MD, Alzari PM, Fournier JM, Taylor RK, Kováč P, Wade WF. Induction of protective immunity by synthetic Vibrio cholerae Hexasaccharide derived from Vibrio cholerae O:1 Ogawa lipopolysaccharide bound to a protein carrier. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:950–962. doi: 10.1086/339583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Yergey A, Kowalak J, Kováč P. Studies towards neoglycoconjugates from the monosaccharide determinant of Vibrio cholerae O:1, serotype Ogawa using the diethyl squarate reagent. Carbohydr Res. 1998;313:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(98)00261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou S-j, Saksena R, Kováč P. Preparation of glycoconjugates by dialkyl squarate chemistry revisited. Carbohydr Res. 2008;343:196–210. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Kováč P. Synthesis of ligands related to the Vibrio cholerae specific antigen. Part 14 Synthesis of methyl a-glycosides of some higher oligosacchairde fragments of Vibrio cholerae O1, serotype Inaba and Ogawa. Carbohydr Res. 1997;300:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNaught AD. Nomenclature of Carbohydrates. Carbohydr Res. 1997;297:1–92. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)83449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westfal G, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Extraction with phenol-water and further applications of the procedure. Methods Carbohydr Chem. 1965;5:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raziuddin S. Immunochemical Studies of the Lipopolysaccharides of Vibrio cholerae:ConstitutionofO-SpecificSideChainandCore Polysaccharide. Inf and Immun. 1980;27:211–215. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.211-215.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustafsson B, TH Immunological characterization of Vibrio cholerae O:1 lipopolysaccharide, O-side chain, and core with monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1985;49:275–280. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.275-280.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qadri F, Wenneras C, Albert MJ, Hossain J, Mannoor K, Begum YA, Mohi G, Salam MA, Sack RB, Svennerholm AM. Comparison of immune responses in patients infected with Vibrio cholerae O139 and O1. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3571–3576. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3571-3576.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qadri F, Mohi G, Hossain J, Azim T, Khan AM, Salam MA, Sack RB, Albert MJ, Svennerholm AM. Comparison of the vibriocidal antibody response in cholera due to Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal with the response in cholera due to Vibrio cholerae O1. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:685–688. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.6.685-688.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qadri F, Ahmed F, Karim MM, Wenneras C, Begum YA, Abdus Salam M, Albert MJ, McGhee JR. Lipopolysaccharide- and cholera toxin-specific subclass distribution of B-cell responses in cholera. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:812–818. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.6.812-818.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chernyak A, Karavanov A, Ogawa Y, Kováč P. Conjugating Oligosaccharides to proteins by squaric acid diester chemistry; rapid monitoring of the progress of conjugation, and recovery of the unused ligand. Carbohydr Res. 2001;330:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(01)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosley WH, Ahmad S, Benenson AS, Ahmed A. The relationship of vibriocidal antibody titre to susceptibility to cholera in family contacts of cholera patients. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;38:777–785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glass RI, Svennerholm AM, Khan MR, Huda S, Huq MI, Holmgren J. Seroepidemiological studies of El Tor cholera in Bangladesh: association of serum antibody levels with protection. J Infect Dis. 2008;151:236–242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Logvinenko T, Faruque ASG, Ryan ET, Qadri F, Calderwood SB. Susceptibility to Vibrio cholerae infection in a cohort of household contacts of patients with cholera in Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cholera vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec (WHO Publication; no author listed) 2010;85:117–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koelle K, Rodo X, Pascual M, Yunus M, Mostafa G. Refractory periods and climate forcing in cholera dynamics. Nature. 1974;436:696–700. doi: 10.1038/nature03820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cash RA, Music SI, Libonati JP, Craig JP, Pierce NF, Hornick RB. Response of man to infection with Vibrio cholerae. II Protection from illness afforded by previous disease and vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:325–333. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cash RA, Music SI, Libonati JP, Snyder MJ, Wenzel RP, Hornick RB. Response of man to infection with Vibrio cholerae. I Clinical, serologic, and bacteriologic responses to a known inoculum. J Infect Dis. 1974;129:45–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]