Abstract

Manganese(III)-transferrin (Mn(III)-Tf) was investigated as a way to accomplish manganese-labeling of murine hepatocytes for MRI contrast. It is postulated that Mn(III)-Tf can exploit the same transferrin-receptor-dependent and -independent metabolic pathways used by hepatocytes to transport the iron analogue Fe(III)-Tf. More specifically, it was investigated whether manganese delivered by transferrin could give MRI contrast in hepatocytes. Comparison of the T1 and T2 relaxation times of Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf over the same concentration range showed that the r1 relaxivities of the two metalloproteins are the same in vitro; with little contribution from paramagnetic enhancement. The degree of manganese cell labeling following incubation for 2–7 h in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf was comparable to that of hepatocytes incubated in 500 μM Mn2+ for 1 h. The intrinsic manganese tissue relaxivity between Mn(III)-Tf-labeled and Mn2+-labeled cells was found to be the same; consistent with Mn(III) being released from transferrin and reduced to Mn2+. For both treatment regimens, manganese uptake by hepatocytes appeared to saturate in the first 1–2 h of the incubation period and may explain why the efficiency of hepatocyte cell labeling by the two methods appeared to be comparable in spite of the ~16-fold difference in effective manganese concentration. Hepatocytes continuously released manganese, as detected by MRI, and this was the same for both Mn2+- and Mn(III)-Tf-labeled cells. Manganese release may be the result of normal hepatocyte function; much in the same way that hepatocytes excrete manganese into the bile in vivo. This approach exploits a biological process – namely receptor binding, endocytosis, and endosomal acidification – to initiate the release of an MRI contrast agent; potentially confering more specificity to the labeling process. The ubiquitous expression of transferrin receptors by eukaryotic cells should make Mn(III)-Tf particularly useful for manganese labeling of a wide variety of cells both in culture and in vivo.

Keywords: manganese-enhanced MRI, manganese(III)-transferrin, relaxivity, isolated hepatocytes, mouse hepatocytes, iron(III)-transferrin, transferrin receptor, endocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Manganese (Mn2+) has proven to be a useful MR contrast agent for functional imaging (1), neuronal tract tracing (2), and as an anatomical contrast agent (3). The paramagnetic properties of manganese provide localized T1-weighted MRI contrast following the cellular sequestration of Mn2+ (1). Functional imaging using manganese-enhanced MRI (MEMRI) methods assumes Mn2+ acts as a Ca2+ analogue and enters cells via calcium channels. Other mechanisms for manganese delivery into cells are also possible (4) and may play a role in the anatomical contrast detected using MEMRI. For example, transferrins (Tf) – a major class of plasma iron-binding proteins – can accommodate a variety of other metal ions in the two available iron-binding sites of the Tf molecule (5). In particular, Tf has been shown to be one of the major manganese plasma transport proteins in both rodents and humans (6, 7). Another potential pathway for manganese transport across biologic membranes is via the divalent metal ion transporter 1 (DMT-1), which can facilitate the influx/efflux of a number of divalent metal cations, including Mn2+ (8, 9). Lastly, Zn2+ uptake in cultured rat cortical neurons is strongly inhibited by manganese, suggesting that Mn2+ may also serve as a substrate for Zn2+ transporters (10, 11). The fact that manganese transport can be facilitated by a variety of transporters leads to possibilities for exploiting these pathways to deliver Mn2+ for MEMRI studies.

Transferrins are single-strand glycoproteins (~80kDa) containing two structurally similar metal-binding domains (12). Within the hydrophilic cleft of each metal-binding domain, four amino acid residues contribute donor groups that coordinate to the metal ion. For transition metals, the two other metal-coordination sites are occupied by “synergistic anions”(usually carbonate or bicarbonate) which act as bridging ligands between the protein and the metal ion (5). In addition to facilitating the formation and stabilization of the metal-Tf complex, the synergistic carbonate is thought to play an integral role in the subsequent release of the metal ion in low-pH environments within the cell (see below). In the case of manganese, Tf will only bind to the metal ion in the trivalent state (13). In solution under physiological conditions Mn2+ is the most stable form; however, Mn(III)-Tf is the only form of the metalloprotein. Presumably, the presence of oxidizing agents such as ceruloplasmin converts Mn2+ to its trivalent form in plasma (6).

Metal-Tf transport is initiated when the metalloprotein binds to transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) – a transmembrane glycoprotein – at the cell surface (5). The metal-Tf/TfR1 complex is enveloped within a clathrin-coated pit and then transported into the cell via TfR1-mediated endocytosis. In this case, specific binding to the receptor is required to trigger endocytosis. The acidic pH (~5.5) within the resulting endosomal compartment subsequently releases the metal from the internalized protein complex, presumably via protonation of the synergistic carbonate group within each of the Tf metal-binding domains. In the case of manganese, the free Mn3+ should be rapidly reduced to its more stable Mn2+ oxidation state. The hypothesis for the present study is that the divalent Mn2+ can then be transported across the endosomal membrane into the cytosol. This can occur via the divalent metal transporter (DMT-1) (9). The metal-free apo-Tf/TfR1 complex that remains within the endosome can then be recycled back to the cell surface through exocytic vesicles. In the neutral-pH environment (~7.4) of the extracellular fluid, the apo-Tf/TfR1 complex dissociates and both proteins are reused in another cycle of cellular metal-ion uptake. In the case of iron, each Tf molecule is estimated to participate in 100–200 cycles of metal binding, transport, and release during its plasma lifetime in humans (12). Thus it should be possible to use Mn(III)-Tf to load cells with manganese for MEMRI. Indeed, this represents a novel way to use a biological pathway for targeting and to release an MRI contrast agent into cells.

Parenchymal liver cells (hepatocytes) play a major role in maintaining iron homeostasis in the body; employing transferrin as one of the primary iron-transport proteins. Although most eukaryotic cells use receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME) almost exclusively for Fe(III)-Tf uptake, hepatocytes also appear to have a number of transferrin-receptor-independent pathways available for iron accumulation via transferrin (14, 15). For example, non-specific mechanisms, such as pinocytosis (fluid-phase endocytosis), have been suggested as significant contributors to Fe(III)-Tf uptake (15). A redox-mediated model has also been proposed, which depends on metal-Tf binding to TfR1, but yet is independent of RME (14, 16). Finally, a cell-surface interaction not involving TfR1 may also play a role in transferrin-receptor-independent uptake of Fe(III)-Tf; however, the mechanism of this process remains unclear (15). Consequently, based primarily on experiments from isolated cells, there is considerable evidence that other transport mechanisms (in addition to RME) are major contributors to Fe(III)-Tf uptake in hepatocytes. However, all proposed mechanisms will lead to the metal-Tf complex residing in an acidic environment which in turn will initiate metal release.

This study investigates the feasibility of manganese labeling of murine hepatocytes via the transferrin-receptor-dependent and/or -independent metal-transport pathways described above for Fe(III)-Tf. The chemical similarities between manganese and iron (e.g., similar ionic radii; similar valence states – (II) and (III) – under physiological conditions; and similar binding affinities for Tf) suggest that these transport processes have the potential to label cells with relatively high concentrations of manganese using Mn(III)-Tf. Given the cyclic nature of RME, the extent of cellular labeling is not limited by the total number of available cell-surface transferrin receptors since TfR1 can be continuously regenerated following each metal-ion-transport cycle.

EXPERIMENTAL

Mn(III)-Tf Synthesis

Mn(III)-Tf was prepared using a modification of the procedure described by Aisen et al. (13). Metal-free, human Tf (apo-Tf) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO) and 0.4 g of the protein was dissolved in 16.8 mL of 0.1M KCl-0.05M TRIS buffer (pH=7.5). The affinity of human apo-Tf for the rodent TfR1 receptor is similar to that of the endogenous murine form (17). A 0.01M solution of 1:1 Mn(II)-citrate (pH=5.0) was prepared by adding 0.198 g of MnCl2·4H2O to 0.210 g of citric acid monohydrate dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. The pH of the resulting acidic solution (pH≈2.1) was then adjusted to 5.0 with drop-wise addition of 1.0M NaOH. To the buffered apo-Tf solution was added, with stirring, 3.2 mL of the Mn(II)-citrate solution. The apo-Tf/Mn(II)-citrate solution was then made 0.04M in NaHCO3 by adding 0.065 g of the compound. The solution was then gently aerated (to minimize foaming) with 100% O2 for 24 h, with stirring, in order to completely oxidize the Mn2+ to Mn3+ (the required oxidation state for effective binding to Tf). The initially colorless reaction mixture changed to dark brown over the 24-h period. The reaction mixture was then divided between two dialysis cassettes (10,000 MW cutoff) and dialyzed for 30 h against 4.0L of PBS (pH=7.4) with two dialysis-bath changes over the 30-h period. The two dialyzed samples were then combined to yield ~18.5 mL of a clear, dark-brown solution.

The UV-VIS spectrum of Mn(III)-Tf was obtained from a X3 dilution of the dialysate, using PBS as a reference. The UV-VIS spectrum showed absorption bands at 330 and 430 nm, consistent with the spectrum reported by Aisen et al. (13). The absorption band in the visible region (430 nm) was used to estimate the Mn(III)-Tf concentration of the dialysate, based on a molar absorptivity of 9,600 M−1cm−1 (18). The 248 μM dialysate solution contained 0.366 g of Mn(III)-Tf (92% yield).

Hepatocyte Isolation and Labeling

Murine hepatocytes were isolated from male FVB, B6, or B6D2 mice using a collagenase perfusion method (19). Isolated hepatocytes were suspended and cultured in DMEM/F12 + Glutamax (GIBCO 10565-018). Also added to the medium was 10% FBS, 2% Pen/Strep, 1% Insulin/Transferrin/Selenium, 100nM Dexamethasone, and 2mM EGF. Hepatocytes were plated at a density of ~6 × 105 cells/cm2 in T-75 plastic culture flasks and incubated to confluence at 37°C under atmospheric conditions (~24 h). Cell viability (using Trypan Blue staining) of plated hepatocytes was ~85–90%. After reaching confluence, the growth medium was replaced with GIBCO D-MEM/F-12 growth medium (Cat. No. 11039-021; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) containing 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf (typically 10–15 mL, depending upon the number of flasks being treated) and incubated over a range of time periods (2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 h). For control samples, hepatocytes were incubated with growth medium alone.

Following the Mn(III)-Tf incubation period, the growth medium was removed from each flask and saved for subsequent MRI analysis. Each flask was then washed twice with 5–10 mL of sterile Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (Cat. No. 21-022-CV; Mediatech, Inc., Hearndon, VA) to remove any residual serum. To each flask was then added 3.0 mL of trypsin (Trypsin-Versene mixture; Cat. No. 17-161E; BioWhitaker, Walkersville, MD) and the flasks were incubated at 37°C for successive 2–3 min intervals until the cells were detached. A 10-mL volume of GIBCO William’s Media E (Cat. No. 12551-032; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) – which contains serum – was then added to each flask to terminate the trypsinization process. The contents of each flask were then transferred to separate 15-mL conical centrifuge tubes and the cells were pelleted at 50XG for 5 min. The supernatant was then removed and the cells were resuspended in 5 mL of stock D-MEM/F-12 growth medium and then centrifuged again at 50XG for 5 min. After removal of the supernatant, the cell pellets were resuspended in 1.0 mL of stock D-MEM/F-12 growth medium, transferred to a 2.0-mL conical vial, and centrifuged at low speed for 1 min. MRI measurements were performed immediately thereafter.

For comparative studies with Mn2+ alone, hepatocytes were incubated for 1 h in growth media containing 500 μM MnCl2·4H2O(in place of the 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf); all other work-up procedures were the same as those used for Mn(III)-Tf. For comparative studies with Fe(III)-Tf (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO), a 268 μM Fe(III)-Tf stock solution was prepared by dissolving 0.1268 g of the compound in 6.0 mL of PBS. A 31.5 μM Fe(III)-Tf solution was prepared by diluting the stock solution with growth media. Hepatocytes were incubated in the 31.5 μM Fe(III)-Tf growth medium for 2-, 3.75-, and 5.75-h time periods; all other work-up procedures were the same as those used for Mn(III)-Tf. Cell viability was evaluated immediately prior to the final low-speed-centrifugation step in the work-up procedure and averaged 48% for Mn2+-treated hepatocytes and 43% for Fe(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes.

For Mn(III)-Tf relaxivity measurements, concentration standards (10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM) were prepared by diluting the 248 μM Mn(III)-Tf stock solution with PBS. For comparative Fe(III)-Tf relaxivity studies, concentration standards (10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM) were prepared by diluting the 268 μM Fe(III)-Tf stock solution with PBS. T1 and T2 relaxation time measurements on fresh growth media were performed on samples obtained directly from the stock bottles.

MRI Measurements

MRI was performed at 7.0T using a Bruker Biospec console interfaced to a Pharmascan magnet. Sample vials were arrayed in a 2 × 3-vial sample holder and positioned upright in a 59-mm-diameter birdcage RF coil. T1 and T2 relaxation times of the hepatocyte cell pellets, growth media, and concentration standards were determined from calculated T1 and T2 maps. For T1 and T2 measurements of hepatocyte and growth media samples, 8–12 (depending on the number of sample vials) axial slices (i.e., oriented parallel to the long axis of the sample vials and perpendicular to the B0 field) were acquired through the sample-vial array. The slice thickness varied from 2.5–2.7 mm and the slice separation (from center-to-center) was varied from 2.75–3.0 mm, respectively. The slice-packet position was optimized to maximize coverage of the hepatocyte cell pellets in all of the vials and – under these conditions – each cell pellet was often intersected by two adjacent slices. For T1 and T2 measurements of the concentration standards, a single 5-mm-thick slice was acquired perpendicular to the long axis of the sample vials.

T1 measurements were performed using the progressive saturation method with multi-slice, spin-echo images acquired with repetition time (TR) values of 110.2 (or 126 in some cases), 300, 500, 750, 1000, 2000, 4000, and 8000 ms. Other imaging parameters were: echo time (TE) = 10.4 or 11.9 ms; field-of-view (FOV) = 45 mm × 45 mm; data acquisition matrix = 256 × 128 (zero-filled to 256 × 256); and number of averages (NEX) = 1 for the concentration standards and NEX = 2 for the hepatocyte and growth media samples.

T2 measurements were performed using multi-slice, multi-spin-echo imaging. For measuring short-T2-components (e.g., Mn(III)-Tf-, Fe(III)-Tf-, and Mn2+-treated hepatocytes), 40 echoes were acquired with intervening TE values of 10.4, 11.9, or 15.0 ms. For measuring longer-T2-components (e.g., treated and untreated growth media samples), 25 echoes were acquired with intervening TE values of 25 ms. Other imaging parameters were: TR varied from ~1000–10000 ms (depending upon TE, the number of echoes, and the number of slices); FOV = 45 mm × 45 mm or 50 mm × 50 mm; data acquisition matrix = 256 × 128 (zero-filled to 256 × 256); and NEX = 1.

Calculated T1 and T2 maps were obtained using the MRI Analysis Calculator plug-in (v1.0; Karl Schmidt, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA) in ImageJ (20). Following MRI, the cell pellets were evaporated to dryness within their respective sample vials and then submitted for manganese elemental analysis (West Coast Analytical Service, Inc., Santa Fe Springs, CA). Duplicate 1-mL samples of the 248 μM Mn(III)-Tf stock solution were also evaporated to dryness within separate 2-mL conical vials and analyzed for elemental manganese.

Treatment of Elemental Analysis Data

The results from the manganese elemental analyses of the hepatocyte cell pellets were reported as total manganese/dry weight of cellular material (μg/g). Hepatocyte water content was estimated from the formula: (wet weight – dry weight)/dry weight = 3.65 (21). The manganese concentration was then converted to mmole/L (mM).

Data Analysis

For each slice through the cell-containing sample vials, the boundary of the cell pellet in the image was used to define a region of interest (ROI). The T1 and T2 relaxation times of each cell pellet in the slice were then estimated from the respective calculated T1 and T2 relaxation-time maps by averaging the pixel values within the ROIs using ImageJ. For pellets that were intersected by more than one image slice, the T1 and T2 values from the pellet in each slice where averaged to derive the overall relaxation time values for the entire pellet.

For sample vials containing only growth media or concentration standards, an ellipsoidal ROI was defined (using ImageJ) within the signal boundaries of each vial within the image. The T1 and T2 relaxation times of each sample were then estimated from the respective calculated T1 and T2 relaxation-time maps by averaging the pixel values within the ROIs.

Statistical analysis for distinguishing between two normally-distributed sample populations was performed using a one-tailed, Student’s t-test, with unequal variances (Microsoft Office Excel 2003, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA); a value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All P values were corrected (Bonferroni) for multiple comparisons. Linear-least-squares regression analysis and the associated plots were generated using the Scientific Fig.Processor (Fig.P) software package (BIOSOFT, Cambridge, UK; Ferguson, MO, USA). Excel was used to exclude outliers using the Quartile or Fourth-Spread Method (22). GraphPad Prism 5 Software (San Diego, CA) was used to evaluate the statistical similarity between: (1) slopes and intercepts of two linear-least-squares regression lines; and (2) the slope of a linear-least-squares regression line and a line of zero slope.

RESULTS

Elemental analysis of the 248 μM Mn(III)-Tf stock solution used in all of these studies was performed on duplicate 1-mL samples. The manganese content of the metalloprotein was assayed to be 1460 and 1650 μg Mn/g dry weight of Mn(III)-Tf, respectively, for the two samples. Assuming a molecular weight of 80,000 g/mole for the metalloprotein, the mole ratio of manganese to Tf was 2.1 and 2.4, respectively; in good agreement with the expected value of 2.0.

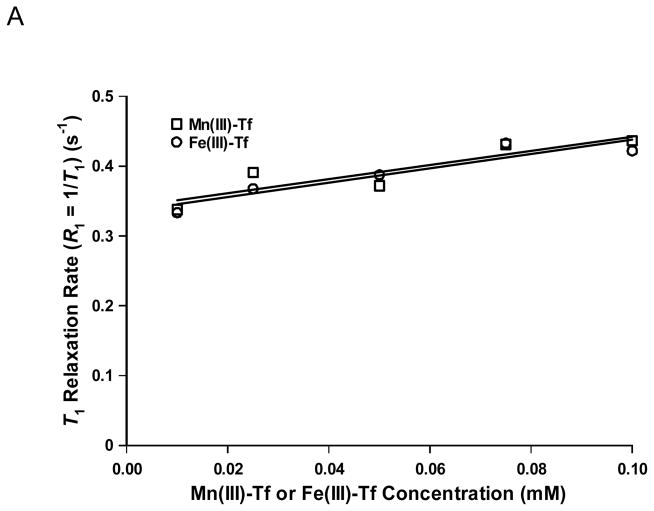

Fig. 1A shows a plot of T1 relaxation rate (R1 = 1/T1; s−1) as a function of concentration for Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf (μM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For Mn(III)-Tf, a linear-least-squares regression fit to the data yielded: R1 (s−1) = 1.0±0.3·[Mn(III)-Tf] (mM) + 0.34±0.02 (r2 = 0.80). The errors on the linear least-squares fitting parameters are ±1 SE. For Fe(III)-Tf, R1 (s−1) = 1.0±0.2·[Fe(III)-Tf] (mM) + 0.34±0.01 (r2 = 0.87). The slopes of the two lines are statistically equal.

Figure 1.

(A) Plot of T1 relaxation rate (R1 = 1/T1; s−1) as a function of concentration for Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf (mM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The r1 relaxivity values for Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf (i.e., the slope of the respective best-fit lines) are statistically equal (1.0±0.3 and 1.0±0.2 s−1mM−1, respectively) and are likely a function of metalloprotein concentration alone. (B) Plot of T2 relaxation rate (R2 = 1/T2; s−1) as a function of concentration for Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf (mM) in PBS. In contrast to r1, the r2 relaxivity of Mn(III)-Tf (21±2 s−1mM−1) is factor of three larger (and statistically different) than that of Fe(III)-Tf (7±2 s−1mM−1).

Fig. 1B shows a plot of T2 relaxation rate (R2 = 1/T2; s−1) as a function of concentration for Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf (mM) in PBS. For Mn(III)-Tf, R2 (s−1) = 21±2·[Mn(III)-Tf] (mM) + 3.0±0.1 (r2 = 0.97); for Fe(III)-Tf, R2 (s−1) = 7±2·[Fe(III)-Tf] (mM) + 2.6±0.1 (r2 = 0.82). The r2 relaxivity values for Mn(III)-Tf (21 s−1mM−1) and Fe(III)-Tf (7 s−1mM−1) are statistically different; to an extent that precluded testing whether the intercepts differed significantly.

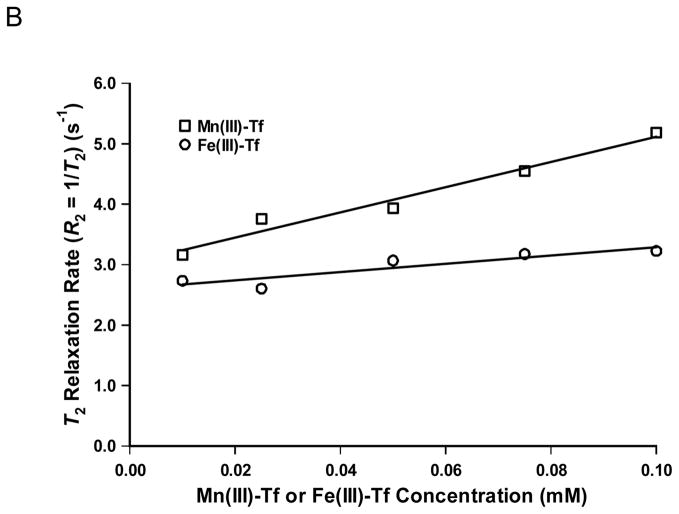

Fig. 2 shows representative T1-weighted MR images [TR/TE = 500/10.4(11.9 for Mn(III)-Tf) ms] of control, Mn(III)-Tf-treated (31.5 μM for 4h), Mn2+-treated (500 μM for 1h), and Fe(III)-Tf-treated (31.5 μM for 2h) murine hepatocytes. The control-cell pellet is outlined in white since the relatively longer T1 relaxation time (2.15 s in this case) makes the control-hepatocyte signal isointense with that of the surrounding stock D-MEM/F-12 growth medium. The similar T1 values of Mn(III)-Tf-treated (0.61 s) and Mn2+-treated (0.54 s) hepatocytes in this example yield comparable T1-weighted signal enhancement under these conditions. The T1 relaxation time of Fe(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes (1.60 s) yields T1-weighted signal enhancement between that of the control and the Mn(III)-Tf-treated and Mn2+-treated hepatocytes.

Figure 2.

T1-weighted MR images of control (outlined in white), Mn(III)-Tf-treated (31.5 μM for 4h), Mn2+-treated (500 μM for 1h), and Fe(III)-Tf-treated (31.5 μM for 2h) murine hepatocytes. The acquisition parameters are: TR = 500 ms; TE = 10.4 ms (except for Mn(III)-Tf, where TE = 11. 9 ms); FOV = 45 mm × 45 mm (cropped above to 16.4 mm × 30.0 mm for each sample vial); slice thickness = 2.5 mm (Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes), 2.6 mm (Fe(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes), and 2.7 mm (control and Mn2+-treated hepatocytes). Solution above hepatocyte cell pellets is stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media (see text for details). Images are intensity-scaled to be approximately comparable to each other.

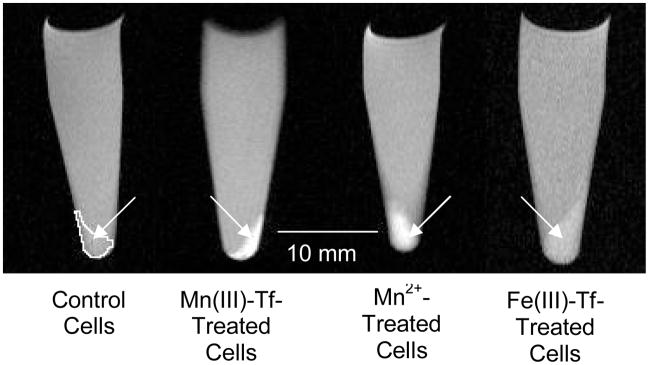

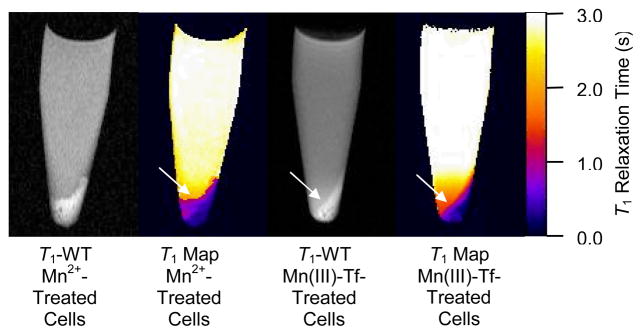

Fig. 3 shows T1-weighted MR images (TR/TE = 500/10.4 ms) and calculated T1 maps of Mn2+-treated (500 μM for 1 h) and Mn(III)-Tf-treated (31.5 μM for 3 h) hepatocytes. The solution above the hepatocyte cell pellets is stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media. For both Mn2+-treated and Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes, there is a T1-signal-enhancement gradient in the growth media adjacent to the cell-pellet boundary. Notice that the T1-relaxation-time gradient is significantly more pronounced in the vicinity of the Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes as compared to the Mn2+-treated sample. This prominent T1 gradient was also observed in two other Mn(III)-Tf samples (data not shown) and was consistently more pronounced than that of the Mn2+-treated samples.

Figure 3.

T1-weighted MR images (TR/TE = 500/10.4 ms) and calculated T1 maps of Mn2+-treated (500 μM for 1 h) and Mn(III)-Tf-treated (31.5 μM for 3 h) murine hepatocytes. The solution above the hepatocyte cell pellets is stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media (see text for details). The color scale for the calculated T1 maps is the same for both Mn2+- and Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes. There is a prominent T1-signal-enhancement gradient in the growth media adjacent to the cell-pellet boundary, which is most apparent in the T1-weighted MR image of the Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes (see arrow). This T1-relaxation-time gradient is better appreciated in the calculated T1 maps for each sample (see arrows); particularly for the Mn2+-treated hepatocytes, where the effect is more subtle. These observations are consistent with hepatocytes releasing internalized Mn2+, much in the same way that hepatocytes attempt to excrete Mn2+ into the bile in vivo.

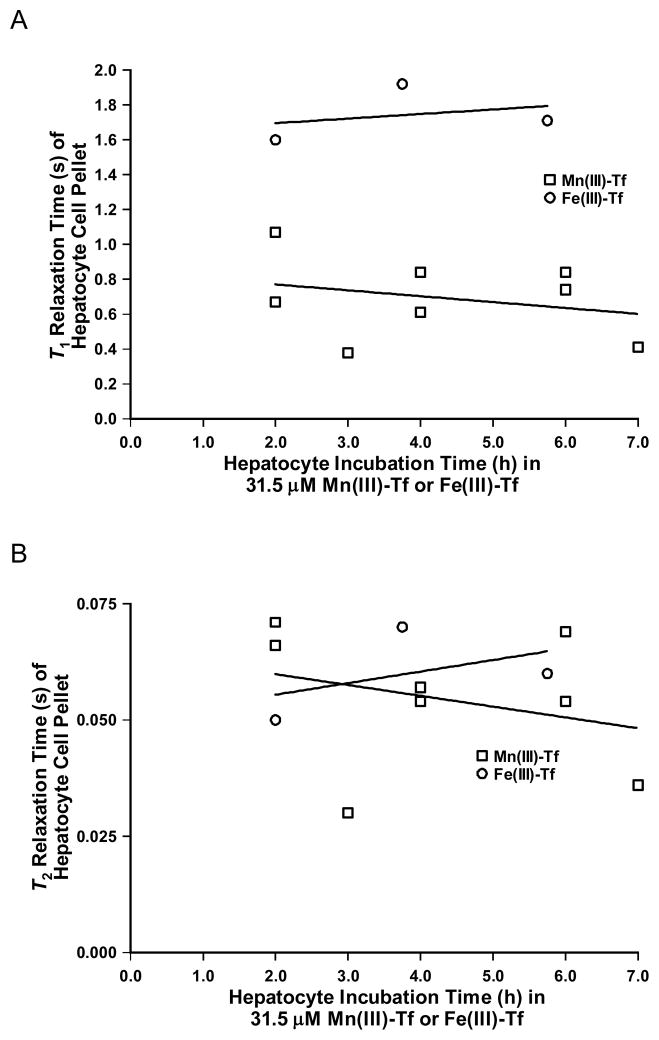

Fig. 4A shows a plot of T1 relaxation time (s) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of hepatocyte incubation time in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf or Fe(III)-Tf (h). The best-fit linear regression lines for both Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf had r2 values less than 0.1 and slopes that were not significantly different from zero. Consequently, there is no dependence of the T1 relaxation time on hepatocyte incubation time in either 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf or Fe(III)-Tf over the time period from 2–7 h.

Figure 4.

(A) Plot of T1 relaxation time (s) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of incubation time (h) in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf or Fe(III)-Tf. (B) Plot of T2 relaxation time (s) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of incubation time (h) in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf or Fe(III)-Tf. The deviation of the slopes of the best-fit linear regression lines from zero was not significant for either Mn(III)-Tf or Fe(III)-Tf in (A) or (B); indicating that there was essentially no dependence of the T1 or T2 relaxation times on hepatocyte incubation time over this time period.

Fig. 4B shows a plot of T2 relaxation time (s) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of hepatocyte incubation time in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf or Fe(III)-Tf (h). The best-fit linear regression lines for both Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf had r2 values of 0.09 and 0.25, respectively, and slopes that were not significantly different from zero. Consequently, there is no dependence of the T2 relaxation time on hepatocyte incubation time in either 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf or Fe(III)-Tf over the time period from 2–7 h. Since both the T1 and T2 relaxation times of hepatocytes appear to be independent of incubation time under these conditions, the hepatocyte relaxation time values for the different incubation-time periods were pooled to calculate the average values of T1 and T2 for a particular treatment regimen (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean T1 and T2 relaxation times (s) and relaxation rates (s−1) for murine hepatocytes and incubation growth media as a function of treatment regimen. Hepatocytes were incubated in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf (for time periods varying from 2–7 h; see Fig. 4), 500 μM Mn2+ (for 1 h), or 31.5 μM Fe(III)-Tf (for time periods varying from 2.0–5.75 h; see Fig. 4) prepared in stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media (see text for details). Control hepatocytes were incubated in stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media alone. Hepatocyte-incubation-media samples were acquired at the conclusion of each incubation period. Stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media samples were taken directly from the stock bottle. The number of hepatocyte or hepatocyte-incubation-media samples is given in parentheses following the table entry for each sample. Values are reported as mean ± 1 standard deviation (SD).

| Hepatocyte or Hepatocyte-Incubation-Media Sample | T1±1 SD (s) | R1±1 SD (s−1) | T2±1 SD (s) | R2±1 SD (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn(III)-Tf-Treated Hepatocytes (N = 8) | 0.7±0.2 | 1.6±0.6 | 0.05±0.01 | 20±7 |

| Mn2+-Treated Hepatocytes (N = 8) | 0.9±0.4 | 1.3±0.4 | 0.07±0.02 | 16±5 |

| Fe(III)-Tf-Treated Hepatocytes (N = 3) | 1.7±0.2 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.06±0.01 | 18±2 |

| Control Hepatocytes (N = 7) | 2.3±0.2 | 0.45±0.06 | 0.09±0.01 | 12±2 |

| Mn(III)-Tf-Treated Hepatocyte-Incubation Media (N = 8) | 1.9±0.2 | 0.52±0.06 | 0.136 (2 h)1 0.116 (7 h) |

2 |

| Mn2+-Treated Hepatocyte-Incubation Media (N = 9) | 0.42±0.06 | 2.4±0.4 | 0.025±0.002 | 40±3 |

| Fe(III)-Tf-Treated Hepatocyte-Incubation Media (N = 3) | 2.9±0.1 | 0.35±0.01 | 0.223±0.003 | 4.5±0.1 |

| Control Hepatocyte-Incubation Media (T1, N = 8; T2, N=4) | 3.0±0.2 | 0.33±0.02 | 0.30±0.01 | 3.3±0.1 |

| Stock Growth Media (T1, N = 4; T2, N=2) | 3.2±0.3 | 0.31±0.03 | 0.32±0.02 | 3.2±0.02 |

The T2 data were correlated as a function of time (r2 = 0.69) and therefore were not pooled to calculate a mean value. The reported T2 values were calculated from the best-fit line through the data (N = 8) at the endpoints of the incubation period.

Could not be calculated.

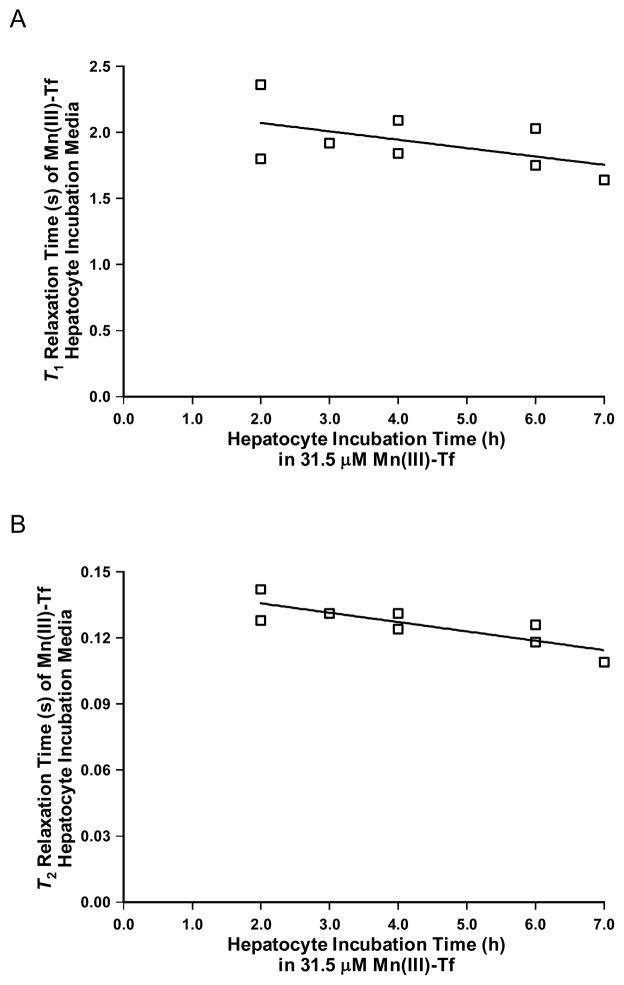

Fig. 5A shows a plot of T1 relaxation time (s) of Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation media as a function of incubation time (h) in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf. The best-fit linear regression lines for Mn(III)-Tf had an r2 value of 0.28 and a slope that was not significantly different from zero; indicating that there is no dependence of the T1 relaxation time of the Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation media on incubation time over the time period from 2–7 h.

Figure 5.

(A) Plot of T1 relaxation time (s) of Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation growth media as a function of incubation time (h) in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf. The deviation of the slope of the best-fit linear regression line from zero was not significant; indicating that there is essentially no dependence of the T1 relaxation time of the Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation growth media on incubation time over the time period from 2–7 h. (B) Plot of T2 relaxation time (s) of Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation growth media as a function of incubation time (h) in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf. The deviation of the slope of the best-fit linear regression line from zero was statistically significant; indicating that there is a dependence of the T2 relaxation time of the Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation growth media on incubation time over the time period from 2–7 h. This result is consistent with hepatocyte release of internalized Mn2+ into the incubation medium over the course of the incubation period.

Fig. 5B shows a plot of T2 relaxation time (s) of Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation media as a function of incubation time (h) in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf. The best-fit linear regression is: T2 (s) = −0.004±0.001·(Mn(III)-Tf Incubation Time; h) + 0.144±0.005 (r2 = 0.69). The deviation of the slope of the best-fit linear regression line from zero was statistically significant; indicating that there is a dependence of the T2 relaxation time of the Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation media on incubation time over the time period from 2–7 h.

Table 1 shows the mean (±1 SD) T1 relaxation times (s) and relaxation rates (s−1) of murine hepatocytes and incubation growth media samples for the various treatments regimens. For hepatocytes incubated in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf, 500 μM Mn2+, or 31.5 μM Fe(III)-Tf, the mean T1 values decrease [following the trend Mn(III)-Tf (0.7±0.2 s) < Mn2+ (0.9±0.4 s) < Fe(III)-Tf (1.7±0.2 s)] relative to that of the control hepatocytes (2.3±0.2 s). For the growth media samples used to incubate the hepatocytes, the mean T1 values decrease [following the trend Mn2+ (0.42±0.06 s) < Mn(III)-Tf (1.9±0.2 s) < Fe(III)-Tf (2.9±0.1 s)] relative to that of the growth media used to incubate the control hepatocytes (3.0±0.2 s).

Table 1 also shows the mean (±1 SD) T2 relaxation times (s) and relaxation rates (s−1) of murine hepatocytes and incubation growth media samples for the various treatments regimens. For hepatocytes incubated in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf, 500 μM Mn2+, or 31.5 μM Fe(III)-Tf, the mean T2 values are similar [Mn(III)-Tf (0.05±0.01 s) ≈ Mn2+ (0.07±0.02 s) ≈ Fe(III)-Tf (0.06±0.01 s)]. For the growth media samples used to incubate the hepatocytes, the T2 values decrease {following the trend Mn2+ [0.025±0.002 s] < Mn(III)-Tf [0.136 s (2 h) – 0.116 s (7 h)] < Fe(III)-Tf [0.223±0.003 s]} relative to that of the growth media samples used to incubate the control hepatocytes (0.30±0.01 s).

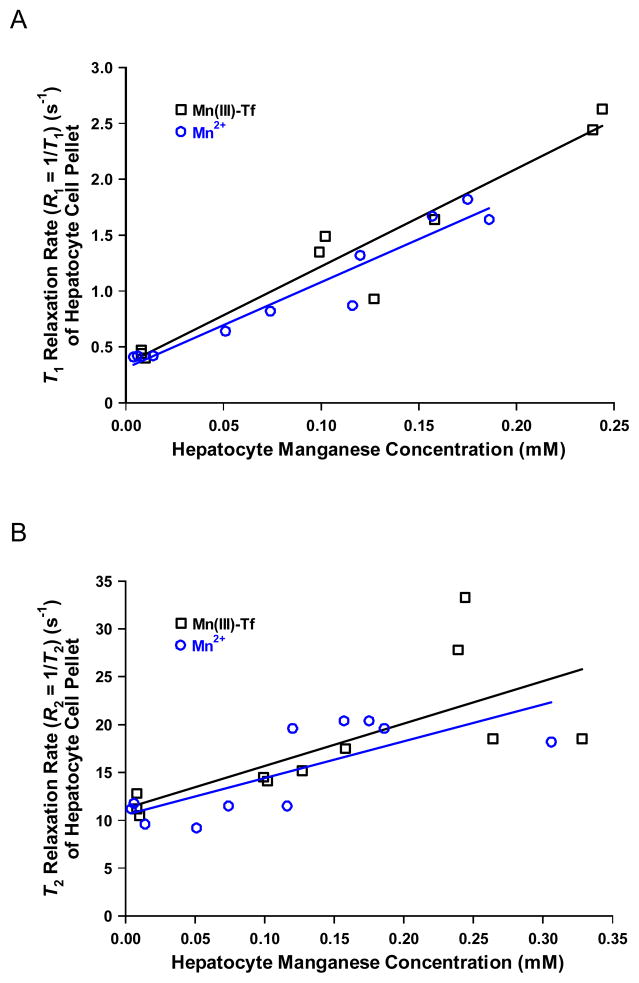

Fig. 6A shows a plot of T1 relaxation rate (R1 = 1/T1; s−1) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of hepatocyte manganese concentration (mM) following incubation in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf (for time periods ranging from 2–7 h; see Fig. 4A), 500 μM Mn2+ (for 1 h), or stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media alone. For Mn(III)-Tf, the best-fit linear regression line is: R1 (s−1) = 8.7±0.9·[Mn] (mM) + 0.34±0.13 (r2 = 0.93). For Mn2+, the best-fit linear regression line is: R1 (s−1) = 7.7±0.7·[Mn] (mM) + 0.31±0.08 (r2 = 0.93). For the Mn(III)-Tf data, two outliers ([Mn] = 0.264 mM; R1 = 1.19 s−1; and [Mn] = 0.328 mM, R1 = 1.19 s−1) were excluded from the data set based on the Quartile or Fourth-Spread Method(22), prior to performing the linear-least-squares regression analysis. For the Mn2+ data, one outlier ([Mn] = 0.306 mM, R1 = 1.49 s−1) was excluded from the data set using the same method (22). A statistical comparison between the two linear-least-squares regression lines in Fig. 6A reveal that both the slopes and the intercepts were statistically the same for the Mn(III)-Tf- and Mn2+-treatment regimens.

Figure 6.

(A) Plot of T1 relaxation rate (R1 = 1/T1; s−1) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of hepatocyte manganese concentration (mM) following incubation in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf (for time periods ranging from 2–7 h; see Fig. 4A), 500 μM Mn2+ (for 1 h), or stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media alone (the data points at [Mn2+] ≈ 0.01 mM). Both the slopes and intercepts of the respective best-fit lines through the data are statistically the same. (B) Plot of T2 relaxation rate (R2 = 1/T2; s−1) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of hepatocyte manganese concentration (mM) following incubation in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf (for time periods ranging from 2–7 h; see Fig. 4A), 500 μM Mn2+ (for 1 h), or stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media alone. Both the slopes and intercepts of the respective best-fit lines through the data are statistically the same.

Fig. 6B shows a plot of T2 relaxation rate (R2 = 1/T2; s−1) of hepatocyte cell pellets as a function of hepatocyte manganese concentration (mM) following incubation in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf (for time periods ranging from 2–7 h; see Fig. 4A), 500 μM Mn2+ (for 1 h), or stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media alone. For Mn(III)-Tf, the best-fit linear regression line is: R2 (s−1) = 44±15·[Mn] (mM) + 11±3 (r2 = 0.50). For Mn2+, the best-fit linear regression line is: R2 (s−1) = 38±11·[Mn] (mM) + 11±2 (r2 = 0.58). The Quartile or Fourth-Spread Method (22) did not identify any outliers in either of these data sets. As is the case in Fig. 6A, a statistical comparison between the two linear-least-squares regression lines in Fig. 6B reveal that both the slopes and the intercepts were statistically the same for the Mn(III)-Tf- and Mn2+-treatment regimens.

It should be mentioned that the internalized manganese that was released into the surrounding growth media during the MRI studies (see Fig. 3) is included in the elemental manganese analyses (as shown in Fig. 6). Following MRI, the cell pellets (as well as the surrounding growth media) were evaporated to dryness within their respective sample vials. The contents of each vial were then quantitatively removed and analyzed for elemental manganese.

DISCUSSION

This study investigates the feasibility of using Mn(III)-Tf for manganese labeling of murine hepatocytes via the same transferrin-receptor-dependent and/or -independent metal-transport pathways used by Fe(III)-Tf. The chemical similarities between manganese and iron [e.g., similar ionic radii; similar valence states – (II) and (III) – under physiological conditions; and similar binding affinities for Tf] suggest that the iron transport processes mentioned above can potentially be exploited to label cells with manganese using the Mn(III)-Tf analogue. The cell-labeling efficiency of Mn(III)-Tf was compared to that of Mn2+ alone; which has been shown to be an effective cell-labeling agent for lymphocytes and isolated pancreatic beta cells (23, 24). The NMR and cell-labeling properties of Mn(III)-Tf were also compared with those of Fe(III)-Tf to better characterize the NMR relaxation-time and transport behavior of Mn(III)-Tf relative to that of the iron analogue.

Comparison of the T1 and T2 relaxation times of the Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf concentration standards (Figs. 1A and 1B) provide some interesting insights into the relative similarities and differences between the two compounds over the same concentration range (which also encompassed that used in the cell-labeling studies in this investigation). In the T1 comparison (Fig. 1A), the slopes (i.e., r1 relaxivities) and intercepts of the two best-fit regression lines are statistically equal (1.0 s−1mM−1 and 0.34, respectively). Since both Mn(III) and Fe(III) are fully coordinated within the hydrophilic cleft of each Tf metal-binding domain, inner-sphere coordinate covalent bonding between the metal and surrounding water molecules is precluded. Furthermore, since coordinatively-saturated Mn(III) is effectively shielded from the aqueous solvent when sequestered in the two Tf-binding domains far from the protein surface, outer-sphere relaxation is not likely to be a significant contributor to the total relaxivity. Consequently, the r1 relaxivities for both Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf appear to be largely a function of Tf concentration alone; with little contribution from paramagnetic Mn(III) enhancement. This assertion is consistent with the report of Koenig and Brown (25), which indicated that Mn3+ in transferrin gives little measurable relaxation contribution.

NMR relaxation data for other Mn(III) complexes are limited and confined mainly to metaloporphyins (26). Furthermore, these compounds are not coordinatively saturated; as would be expected for Mn(III)-transferrin. However, for coordinatively-saturated Mn(II) complexes (e.g., Mn(II)-DTPA, Mn(II)-EGTA, and Mn(II)-NOTA), inner-sphere relaxation effects are minimized resulting in relatively low r1 values (e.g., ~1.6 s−1mM−1 at higher fields such as 60 MHz). The Fe(III)-Tf r1 value measured in the current study is also in accord with that of the coordinatively-saturated Fe(III)-DTPA complex (r1 = 0.83 s−1mM−1 at 60 MHz). Consequently, the r1 value of 1.0 s−1mM−1 for both Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf is consistent with both metals being bound in coordinatively-saturated environments within the metalloprotein.

The T1 study also confirmed that there was little (if any) non-specific adsorption of Mn2+ to the Mn(III)-Tf complex following the synthetic procedure and subsequent dialysis. For example, if Mn2+ was non-specifically adsorbed on the Mn(III)-Tf surface – and accessible to water exchange – an increase in water r1 might be expected due to an increase in rotational correlation time for the metal iassociated with the protein. If this were the case, the r1 values of Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf would probably have been different, if this additional contribution to r1 – other than protein concentration alone – was present. The absence of non-specific adsorption is also supported by the elemental manganese analysis of the purified Mn(III)-Tf used in these studies, which was in good agreement with the expected mole-ratio value of 2.0. These data are therefore consistent with the assumption that all of the manganese is completely sequestered within the metal-Tf binding domains.

The results of these studies suggest that murine hepatocytes can be effectively labeled with manganese using Mn(III)-Tf and at a much lower incubation concentration as compared to that of Mn2+ alone. As shown in Fig. 2, the degree of manganese cell labeling by 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf is comparable to that of 500 μM Mn2+ under these conditions (based on the similarities between their respective T1 and T2 relaxation times; see Table 1). These similarities do not appear to be due to differences in intrinsic Mn2+ tissue relaxivity between Mn(III)-Tf- and Mn2+-labelled cells; since both the r1 and r2 relaxivities are the same for both labeling regimens (as shown in Fig. 6).

In addition to the in vivo r1 and r2 relaxivities for both Mn(III)-Tf and Mn2+ being the same, the absolute values are similar to those reported for aqueous Mn2+. In vitro r1 relaxivity values for Mn2+ are on the order of 7–8 s−1mM−1 for magnetic field strengths above 1.5T, while the r2 relaxivity values are in the range 30–125 s−1mM−1 (27). The r1 value of the Mn2+ aquoion has also been measured in this laboratory to be 7.9 s−1mM−1 at 7.0T (unpublished data). In vivo relaxivity constants have been reported to be up to one order of magnitude higher than those in vitro, due to binding of Mn2+ to macromolecules (28, 29). Intracellular Mn2+ in rat hepatocytes has been shown to be partitioned between cytosolic and noncytosolic compartments (e.g., mitochondria); with the cytosolic ion tightly bound by macromolecules (30). Consequently, increased in vivo Mn2+ relaxivity, relative to the in vitro value, might also be expected for hepatocytes (31). However, large differences between in vitro and in vivo Mn2+ relaxivities were not observed for hepatocytes in this study. One explanation for this similarity is that molecular-correlation-time effects on relaxivity at 7.0T are likely reduced compared to the relatively low-field (e.g., 0.5 – 2.0T) measurements performed in earlier studies (28, 29). Alternatively, if some fraction of the manganese is sequestered such that Mn2+ is inaccessible to water, then the “apparent” in vivo r1 relaxivity would be reduced to a value more similar to that in vitro.

Although the Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocyte sample in Fig. 2 was incubated for a longer period of time (4 h) as compared to 500 μM Mn2+-treated hepatocytes (1 h), the amount of manganese cellular uptake was comparable (again based on the similarities between their respective T1 and T2 relaxation times). In fact, both the T1 and T2 relaxation times of Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes were independent of incubation time over the time period from 2–7 h (as shown in Fig. 4), suggesting that manganese uptake by murine hepatocytes incubated in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf may saturate at some point during the initial 2-h incubation period. In the case of Mn2+-treated hepatocytes (rat liver slices incubated in vitro), it has been shown that Mn2+ uptake saturates within the first 30 min of the incubation period with 100 μM Mn2+ (32). Since the Kap in the Galeotti et al. (32) studies was observed at ~100 μM Mn2+, the Mn2+ uptake observed in the current study (following incubation in 500 μM Mn2+ for 1 h) is also expected to be saturated. Consequently, if the hepatocyte Mn2+ uptake is saturated for both of the Mn(III)-Tf- and Mn2+-treatment regimens used in this study, it may explain the similarities between the T1 and T2 relaxation times under these conditions; in spite of the almost 16-fold difference in effective manganese concentration between the two treatment regimens.

Another interesting observation during the course of these studies was the apparent release of internalized manganese from the hepatocytes during the MRI studies (as shown in Fig. 3). Although observed for both Mn2+- and Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocytes, the amount of internalized manganese released following the latter treatment regimen was much more significant; based upon differences in T1 and T2 (data not shown) relaxation times of the grow media adjacent to the cell-pellet boundaries (see quantitative T1-relaxation-time color scale in Fig. 3). Although some portion of the manganese release may be from non-viable cells that did not survive the incubation procedure, precedent for these observations has been reported for cultured human hepato-carcinoma (Hep-G2) cells. The proposed model of hepatic manganese metabolism is similar to that of isolated rat hepatocytes (33). Hep-G2 cells that were pulsed for 15 min with 54Mn (in a defined salt buffer containing 0.1 μM total manganese), and then placed into a non-radioactive medium, quickly released a large fraction of their internalized manganese. For example, in the first 2 h following the 54Mn pulse, the cellular manganese concentration declined by ~25%, with most of the decrease occurring in the first hour. Given that the MRI measurements in the current study were all performed within the first 1–2 h following collection of the hepatocytes from culture, and that the stock D-MEM/F-12 growth media above the hepatocytes initially contained no Mn2+, these results are consistent with those of the Hep-G2 cell studies.

There is also support in the current study for internalized manganese release into the incubation medium during the actual treatment period. If this occurs, it would be expected that the T1 and T2 relaxation times of the incubation medium would be reduced following the treatment period, relative to their pre-incubation values. Based on the Mn(III)-Tf calibration curves in Figs. 1A and 1B, the T1 and T2 relaxation times of 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf in PBS are estimated to be 2.7 and 0.27 s, respectively; well above the post-treatment values of the Mn(III)-Tf-treated hepatocyte incubation-media samples at the same concentration (1.9 and 0.13 s, respectively; see Table 1). Furthermore, since the slopes (i.e., r1 relaxivities) and intercepts of the Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf calibration curves in PBS are essentially identical, the pre-incubation T1 value of 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf in growth media would be expected to be similar to that of Fe(III)-Tf in growth media at the same concentration. Since the mean post-incubation T1 value of 31.5μM Fe(III)-Tf in growth media is 2.9 s (Table 1), and assuming that no iron is released into the incubation medium during the incubation period, it is reasonable to expect that the pre-incubation T1 relaxation time of 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf in growth media is between 2.7 and 2.9 s. Consequently, the ~1-s decrease in the post-treatment T1 value of the Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation growth media (relative to the expected pre-incubation value) clearly supports the contention that internalized manganese is released both during the incubation period as well as in the first 1–2 h following hepatocyte isolation from culture. Furthermore, although the T1 relaxation time of the Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation growth media does not show a statistically significant dependence on incubation time over the 2–7 h time period (Fig. 5A), there is a statistically significant dependence of the T2 relaxation time of the Mn(III)-Tf hepatocyte incubation growth media as a function of incubation time (Fig. 5B) over the same time period (again consistent with the release of internalized manganese).

In the case of 500 μM Mn2+-treatment, it is doubtful that internalized manganese release from hepatocytes could be detected based on T1-relaxation-time differences between the pre- and post-treatment incubation medium. As shown in Fig. 3, the internalized manganese release following 500 μM Mn2+ treatment is much more difficult to detect than that following incubation in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf. In this case, the concentration of the released manganese would be relatively low compared to the 500 μM Mn2+ incubation medium, making it difficult to measure a relatively small change in what is already a significantly reduced T1 value (0.42 s; Table 1). Although difficult to detect by NMR, the release of internalized manganese during incubation with Mn2+ alone has also been observed in Hep-G2 cells using 54Mn isotopic studies (33); suggesting that it does in fact occur.

Release of manganese after cell loading is a problem for all labeling studies. However, it may offer an advantage. For example, manganese is actively accumulated in the liver and secreted into the bile against a strong concentration gradient (34). Although the mechanism by which manganese moves from the plasma to the bile is still not well understood, recent studies in Hep-G2 cells (33) suggest that it is an active, energy-requiring process that may involve lysosomal packaging and transport. There is strong evidence in the current study that internalized manganese is released from hepatocytes both during the incubation period (Fig. 5B and Table 1) as well as following hepatocyte isolation from culture (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with those of Finley (33) and suggest that internalized manganese release may simply be the result of normal hepatocyte metabolism; much in the same way that hepatocytes excrete manganese into the bile in vivo. In this case, manganese release from hepatocytes and liver could be exploited as an MR assay of normal liver function. Furthermore, there is also interest in developing MR assays for viability and function of hepatocytes (35) and other cell types (24) after transplantation. For these and other applications, MEMRI monitoring of Mn2+ release via normal cellular processes offers interesting possibilities for future work.

The uptake of manganese by hepatocytes incubated in Mn2+ alone is thought to proceed by different mechanisms than those for Mn(III)-Tf. Studies by Galeotti et al. (32), using in vitro incubation of rat liver slices in Mn2+, suggest that hepatocytes have three apparently saturable routes for manganese entry. These are (1) a low-affinity mechanism with Kap in the region of 100 μM; (2) a moderately-high-affinity mechanism with Kap in the range of 0.5–2 μM; and (3) a high-affinity mechanism that operates with a Kap of 0.075 μM. The first mechanism is thought to correspond to a route where Mn2+ substitutes for Ca2+ and can traverse receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in liver and other cells over the 500–1000 μM concentration range (36, 37). For the second mechanism, Mn2+ is postulated to substitute for Ca2+ and enter the cell via the Na/Ca-exchange carrier (32). Since the two relatively high-affinity Mn2+ uptake mechanisms operate in the physiological concentration range for total plasma manganese (~0.1 μM), it is likely that the low-affinity mechanism (i.e., Kap ~100 μM) plays a significant role in the current study, given the 500 μM Mn2+ incubation growth media used in these studies. The transport mechanism responsible for the low-affinity mechanism has yet to be elucidated.

In contrast to transport mechanisms that employ Mn2+ as a Ca2+ analogue, manganese cell labeling of hepatocytes with Mn(III)-Tf likely proceeds via alternative pathways. The most obvious are those employed by the iron analogue, Fe(III)-Tf, which is taken up by eukaryotic cells almost exclusively via receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME). In the case of hepatocytes, there are also a number of transferrin-receptor-independent pathways (summarized in the Introduction) available for iron accumulation via transferrin (14,15). Consequently, given the chemical similarities between manganese and iron, it is reasonable to assume that these same iron transport processes can be exploited to label cells with manganese using the Mn(III)-Tf analogue.

The efficiency of hepatocyte cell labeling with 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf is comparable to that of 500 μM Mn2+ under the conditions used in the current study. One explanation for these results is that the cyclical nature of TfR1-mediated endocytosis has the potential to label cells with relatively high concentrations of manganese, even using relatively low concentrations of Mn(III)-Tf. Furthermore, the efficiency of metal-Tf transport via transferrin-receptor-independent pathways, such as pinocytosis (which is also cyclical), may actually be much greater than via receptor-mediated endocytosis (14), making this a particularly attractive approach for practical manganese cell labeling of hepatocytes.

The relatively lower cytotoxicity of Mn(III)-Tf allowed incubation of the hepatocytes for much longer labeling times (2–7 h) – and at a much lower effective manganese concentration – as compared to the 1-hr time limit imposed by the use of 500 μM Mn2+. However, as observed in Fig. 4, increasing the Mn(III)-Tf incubation time did not significantly increase hepatocyte uptake of manganese. These results suggest that manganese uptake by hepatocytes incubated in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf saturates at some point during the first 2 h of the incubation period. Manganese uptake by hepatocytes incubated in 500 μM Mn2+ for 1 h was also saturated and may explain why the efficiency of hepatocyte cell labeling by the two methods appeared to be comparable in spite of the ~16-fold difference in effective manganese concentration. Another factor that may limit the efficiency of hepatocyte cell labeling using either Mn2+ or Mn(III)-Tf is the internalized manganese release that occurs both during the incubation period as well as after hepatocyte isolation. It may be the case that at some point early in the incubation period, the rate of internalized manganese release equilibrates with the rate of manganese uptake by the hepatocytes, resulting in a relatively constant steady-state hepatocyte manganese concentration over time. In spite of this potential limitation, the ubiquitous expression of transferrin receptors by eukaryotic cells should make Mn(III)-Tf particularly useful for manganese labeling of a wide variety of cells both in culture and in vivo.

There is some question about whether the intracellular fate of Mn2+ differs depending up the methods of delivery; that is, via voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) – in the case of Mn2+ alone – or via RME using Mn(III)-Tf. There is preliminary evidence from this laboratory that some portion of the Mn2+ delivered via RME may end up in the same sub-cellular compartments as compared to Mn2+ delivered via VGCCs. For example, in vivo Mn2+ transport studies following direct intracerebral injections of either Mn2+ or Mn(III)-Tf in the rat have shown that the subsequent white matter tract-tracing efficiency of Mn2+ was the same in both cases (unpublished results from this laboratory). On the other hand, it may be the case that distinct transport chaperones are present following the initial arrival of Mn2+ in the cytosol by each process; which could then redirect Mn2+ to different sub-cellular compartments. However, support this hypothesis is limited in the case of Mn2+.

The stability of the metal-protein complex is a crucial consideration for any biological applications that might employ Mn(III)-Tf as an MRI contrast agent. An estimate for the stability constant of Mn(III)-Tf is ~1010 M−1 (38) and that for Fe(III)-Tf is ~1022 M−1 (39). Consistent with competitive binding studies of manganese in human and rat plasma, manganese did not bind to Tf as strongly as iron, but was considerably better than zinc and cadmium (40). For example, iron in Fe-saturated Tf could not be displaced by manganese. However, at normal plasma iron concentrations (0.9–2.8 μg/mL), normal iron binding capacity (2.5–4.0 μg/mL), and at normal Tf concentration in plasma (3 mg/mL) with 2 metal-ion binding sites per molecule (molecular weight ~80,000) of which only 30% are occupied by Fe3+, Tf has available 50 μmole of unoccupied Mn3+ binding site per liter. Consequently, manganese does not need to displace iron in order to bind to Tf in vivo (41).

The high molecular weight of Mn(III)-Tf certainly poses limitations on the maximum dose that might be delivered in vivo. Based on experiments conducted in this laboratory, the solubility of Mn(III)-Tf in PBS is limited to ~2 mM. Nevertheless, even at this concentration, direct intracerebral injection of ~ 2 mM Mn(III)-Tf in the rat striatum resulted in T1 reductions at 7.0T from ~1.4 s to ~0.4 s in the core of the injection site (unpublished data from this laboratory). On T1-weighted MRI at the same field, signal-intensity changes – relative to baseline – routinely exceeded 100% in the same region. As mentioned previously, the efficiency of in vivo neuronal tract tracing in the rat brain – following direct intracerebral injection of Mn(III)-Tf – has been observed to be similar to that of the equivalent dose of Mn2+ (unpublished results from this laboratory).

In regards to MRI contrast enhancement following intravenous injections of Mn(III)-Tf, the possibilities have yet to be investigated in this laboratory. There have been numerous studies to understand better how manganese is distributed, excreted, and accumulated in experimental animals. For example, following intravenous administration in cows, Mn(III)-Tf is removed from the plasma quite slowly, with a half-life of ~3 h. By contrast, free Mn2+ in bovine plasma is very rapidly cleared by the liver and excreted in the bile; at a rate that is ~30 times faster than that of Mn(III)-Tf (42). Consequently, it may in fact be possible to generate detectable MRI contrast via this administration route. Even at low doses of Mn(III)-Tf), the metalloprotein will circulate ~30 times longer in the blood stream relative to the much higher doses of Mn2+ that are often used in experimental studies. In this case, the use of Mn(III)-Tf should provide an opportunity for more targeted delivery of Mn2+ relative to the administration of Mn2+ alone.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of these studies demonstrate that Mn(III)-Tf is an effective MRI contrast agent for labeling murine hepatocytes. Mn(III)-Tf is thought to exploit the same transferrin-receptor-dependent and -independent metabolic pathways used by hepatocytes to transport the iron analogue Fe(III)-Tf. Comparison of the T1 and T2 relaxation times of Mn(III)-Tf and Fe(III)-Tf over the same concentration range showed that the r1 relaxivities of the two metalloproteins are the same in vitro; with little contribution from paramagnetic enhancement. The degree of manganese cell labeling following incubation for 2–7 h in 31.5 μM Mn(III)-Tf was comparable to that of hepatocytes incubated in 500 μM Mn2+ for 1 h. The intrinsic manganese tissue relaxivity between Mn(III)-Tf-labeled and Mn2+-labeled cells was found to be the same; consistent with Mn(III) being released from transferrin and reduced to Mn2+. For both treatment regimens, manganese uptake by hepatocytes appeared to saturate in the first 1–2 h of the incubation period and may explain why the efficiency of hepatocyte cell labeling by the two methods appeared to be comparable in spite of the ~16-fold difference in effective manganese concentration. Hepatocytes continuously released manganese, as detected by MRI, and this was the same for both Mn2+- and Mn(III)-Tf-labeled cells. Manganese release may be the result of normal hepatocyte function; much in the same way that hepatocytes excrete manganese into the bile in vivo.

One of the most interesting aspects of the present study is that it exploits a biological process – namely receptor binding, endocytosis, and endosomal acidification – to initiate the release of an MRI contrast agent. Indeed, the low intrinsic r1 relaxivity of the Mn(III)-Tf and the large T1 changes detected after incubation of hepatocytes with Mn(III)-Tf indicates that Mn3+ is released from the metalloprotein complex within the endosomal compartment, reduced to Mn2+ in the low-pH (~5.5) environment of the endosome, and then transported across the endosomal membrane into the cytosol via the divalent metal transporter DMT-1 (9). Consequently, cellular uptake of Mn2+ via this route involves more than receptor binding alone, conferring significantly more specificity to the entire labeling process. The ubiquitous expression of transferrin receptors by eukaryotic cells should make Mn(III)-Tf particularly useful for manganese labeling of a wide variety of cells both in culture and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

Contract/grant sponsors:

This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Sabbatical leave support from Worcester Polytechnic Institute is gratefully acknowledged (C. Sotak).

References

- 1.Lin Y, Koretsky AP. Manganese ion enhances T1-weighted MRI during brain activation: an approach to direct imaging of brain function. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:378–388. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pautler RG, Silva AC, Koretsky AP. In vivo neuronal tract tracing using manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:740–748. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pautler RG. Biological applications of manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Methods Mol Med. 2006;124:365–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-010-3:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malecki EA, Devenyi AG, Beard JL, Connor JL. Existing and emerging mechanisms for transport of iron and manganese to the brain. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:113–122. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990415)56:2<113::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aisen P. Transferrin, the transferrin receptor, and the uptake of iron by cells. Met Ions Biol Syst. 1998;35:585–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidsson L, Lönnerdal B, Sandström B, Kunz C, Keen CL. Identification of transferrin as the major plasma carrier protein for manganese introduced orally or intravenously or after in vitro addition in the rat. J Nutr. 1989;119:1461–1464. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.10.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Critchfield JW, Keen CL. Manganese+2 exhibits dynamic binding to multiple ligands in human plasma. Metabolism. 1992;41:1087–1092. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90290-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Gunshin Y, Romero MF, Boron WF, Nussberger S, Gollan JL, Hediger MA. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;388:482–488. doi: 10.1038/41343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrick MD, Dolan KG, Horbinski G, Ghio AJ, Higgins D, Porubcin M, Moore EG, Hainsworth LN, Umbreit JN, Conrad ME, Feng L, Lis A, Roth JA, Singleton S, Garrick LM. DMT1: A mammalian transporter for multiple metals. BioMetals. 2003;16:41–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1020702213099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colvin RA, Fontaine CP, Laskowski M, Thomas D. Zn2+ transporters and Zn2+ homeostasis in neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colvin RA. pH dependence and compartmentalization of zinc transported across plasma membrane of rat cortical neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C317–C329. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00143.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aisen P, Enns C, Wessling-Resnick M. Chemistry and biology of eukaryotic iron metabolism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:940–959. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aisen P, Aasa R, Redfield AG. The chromium, manganese, and cobalt complexes of transferrin. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:4628–4633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorstensen K, Romslo I. The role of transferrin in the mechanism of cellular iron uptake. Biochem J. 1990;271:1–10. doi: 10.1042/bj2710001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorstensen K, Trinder D, Zak O, Aisen P. Uptake of iron from N-terminal half-transferrin by isolated rat hepatocytes: Evidence of transferrin-receptor-independent iron uptake. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:129–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorstensen K, Romslo I. Uptake of iron from transferring by isolated hepatocytes. A redox-mediated plasma membrane process? J Biol Chem. 1988;263:884–8850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill JM, Ruff MR, Weber RJ, Pert CB. Transferrin receptors in rat brain: neuropeptide-like pattern and relationship to iron distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4553–4557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirschenbaum DM. Molar absorptivity and values for proteins at selected wavelengths of the ultraviolet and visible regions. XII. Anal Biochem. 1977;80:193–211. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90639-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klaunig JE, Goldblatt PJ, Hinton DE, Lipsky MM, Chacko J, Trump BF. Mouse liver cell culture. I. Hepatocyte isolation. In Vitro. 1981;17:913–925. doi: 10.1007/BF02618288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasband WS. ImageJ. U. S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland, USA: 1997–2006. http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leclercq P, Filippi C, Sibille B, Hamant S, Keriel C, Leverve XM. Inhibitions of glycerol metabolism in hepatocytes isolated from endotoxic rats. Biochem J. 1997;325:519–525. doi: 10.1042/bj3250519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs JL, Dinman JD. Systematic analysis of bicistronic reporter assay data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e160. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh157. http://www.dinmanlab.umd.edu/statistics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Aoki I, Takahashi Y, Chuang KH, Igarashi T, Tanaka C, Childs RW, Koretsky AP. Cell labeling for magnetic resonance imaging with the T1 agent manganese chloride. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:50–59. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gimi B, Leoni L, Oberholzer J, Braun M, Avila J, Wang Y, Desai T, Philipson LH, Magin RL, Roman BB. Functional MR microimaging of pancreatic beta-cell activation. Cell Tranplant. 2006;15:195–203. doi: 10.3727/000000006783982151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koenig SM, Brown RD., III Relaxation of solvent protons by paramagnetic ions and its dependence on magnetic field and chemical environment: implications for NMR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1984;1:478–495. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910010407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauffer RB. Paramagnetic metal complexes as water proton relaxation agents for NMR imaging: theory and design. Chem Rev. 1987;87:901–927. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva AC, Lee JH, Aoki I, Koretsky AP. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI): methodological and practical considerations. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:532–543. doi: 10.1002/nbm.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang YS, Gore JC. Studies of tissue NMR relaxation enhancement by manganese: dose and time dependences. Invest Radiol. 1984;19:399–407. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198409000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nordhoy W, Anthonsen HW, Bruvold M, Brurok H, Skarra S, Krane J, Jynge P. Intracellular manganese ions provide strong T1 relaxation in rat myocardium. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:506–514. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schramm VL, Brandt M. The manganese(II) economy of rat hepatocytes. Federation Proc. 1986;45:2817–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yilmaz A, Yurdakoc M, Isik B. Influence of transition metal ions on NMR proton T1 relaxation times of serum, blood, and red cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1999;67:187–193. doi: 10.1007/BF02784073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galeotti T, Palombini G, van Rossum GDV. Manganese content and high-affinity transport in liver and hepatoma. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;322:453–459. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finley JW. Manganese uptake and release by cultured human hepato-carcinoma (Hep-G2) cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1998;64:101–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klassen C. Biliary excretion of manganese in rats, rabbits and dogs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1974;29:458–468. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(74)90117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landis CS, Yamanouchi K, Zhou H, Mohan S, Roy-Chowdhury N, Shafritz DA, Koretsky A, Roy-Chowdhury J, Hetherington HP, Guha C. Noninvasive evaluation of liver repopulation by transplanted hepatocytes using 31P MRS imaging in mice. Hepatology. 2006;44:1250–1258. doi: 10.1002/hep.21382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renard-Rooney DC, Hajnóczky G, Seitz MB, Schneider TG, Thomas AP. Imaging of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ fluxes in single permeabilized hepatocytes. Demonstration of both quantal and nonquantal patterns of Ca2+ release. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23601–23610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kass GEN, Webb D-L, Chow SC, Llopis J, Berggren P-O. Receptor-mediated Mn2+ influx in rat hepatocytes: comparison of cells leaded with Fura-2 ester and cells microinjected with Fura-2 salt. Biochem J. 1994;302:5–9. doi: 10.1042/bj3020005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris CM, Candy JM, Court JA, Whitford CA, Edwardson JA. The role of trasferrin in the uptake of aluminuun and manganese by the IMR 32 neuroblastoma cell line. Biochem Soc Trans. 1987;15:498–499. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aisen P, Listowsky I. Iron transport and storage proteins. Ann Rev Biochem. 1980;49:357–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheuhammer AM, Cherian MG. Binding of manganese in human and rat plasma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;840:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(85)90115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aschner M, Aschner JL. Manganese neurotoxicity: cellular effects and blood-brain barrier transport. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1991;15:333–340. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibbons RA, Dixon SN, Hallis K, Russel AM, Sansom BF, Symonds HW. Manganese metabolism in cows and goats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;444:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(76)90218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]