Abstract

Obesity is associated with lower brain volumes in cognitively normal elderly subjects, but no study has yet investigated the effects of obesity on brain structure in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer’s disease (AD). To determine if higher body mass index (BMI) is associated with brain volume deficits in cognitively impaired elderly subjects, we analyzed brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 700 MCI or AD patients from two different cohorts: the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and the Cardiovascular Health Study-Cognition Study (CHS-CS). Tensor-based morphometry (TBM) was used to create 3-dimensional maps of regional tissue excess or deficits in subjects with MCI (ADNI, N=399; CHS, N=77) and AD (ADNI, N=188; CHS, N=36). In both AD and MCI groups, higher BMI was associated with brain volume deficits in frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes; the atrophic pattern was consistent in both ADNI and CHS populations. Cardiovascular risk factors, especially obesity, should be considered as influencing brain structure in those already afflicted by cognitive impairment and dementia.

Keywords: Body mass index (BMI), brain structure, tensor-based morphometry, ADNI, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment

1. Introduction

Much ongoing research aims to discover preventable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia. Cardiovascular risk factors have long been known to increase risk for vascular dementia, but an increasing number of studies are linking higher body fat to risk for Alzheimer’s disease. In several epidemiological studies, people with a higher body mass index (BMI) during mid-life have a greater risk for developing AD (Fitzpatrick et al., 2009, Gustafson et al., 2003, Kivipelto et al., 2005, Whitmer et al., 2007). Cognitive function is, on average, somewhat impaired in elderly subjects who are obese (Elias et al., 2003). The neuropathological hallmarks of AD, amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, are also more likely to be expressed in elderly obese persons (Mrak 2009). Vascular factors are also associated with faster cognitive decline and with more rapid progression of AD (Helzner et al., 2009). This work collectively suggests that being overweight or obese may increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease and may be associated with a great level of functional impairment and pathology.

Mid-life obesity is a strong predictor of dementia late in life (Gustafson et al., 2003, Whitmer et al., 2007, Yaffe et al., 2004), but low BMI, later in life, and rapid weight loss have also been linked to dementia in the elderly (Fitzpatrick et al., 2009). Previous studies (Buchman et al., 2005, Johnson et al., 2006) support this dissociation, or “obesity paradox”; even so, body mass index and brain structure in MCI and early AD patients have not previously been correlated.

Adiposity is considered to be a part of a broader syndrome. The co-occurrence of at least three of the following cardiovascular factors including large waist circumference (or adiposity), increased triglycerides, elevated blood pressure, and fasting hyperglycemia has been referred to as “the metabolic syndrome” (Yaffe et al., 2004). Adiposity is also associated with insulin resistance and subsequent type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, degenerative joint disease, cancer and lung problems (Poirier et al., 2006).

Adiposity is typically assessed with anthropometric measures, including the most simple and commonly used measure, BMI, which is calculated as weight (kg)/ height (m2). This ratio was first described in 1832 by Adolphe Quetelet (Eknoyan 2008), and was later confirmed in 1972 by Ancel Keys as the best proxy for body fat percentage (Keys et al., 1972). While BMI is a convenient measure, it has its limitations; ethnicity and age affect BMI, and, starting in mid-life, the ratio of fat-free mass to height decreases with age, especially among women (Barlett et al., 1991). BMI strongly correlates with fat tissue and waist circumference; there is some debate as whether waist circumference is a more sensitive marker of adiposity than BMI (Janssen et al., 2004, Zhu et al., 2004).

Brain structural integrity, as indexed by the volumes of brain substructures, reflects underlying neuronal health; some progressive tissue loss occurs with normal aging but this is greatly accelerated in AD and MCI. To better understand how obesity can raise risk for AD, it is helpful to investigate how it relates to the structural integrity of the brain. In a prior study of cognitively normal elderly adults (Raji et al., 2009a), we found that greater body tissue adiposity as reflected by a higher BMI was associated with lower brain volumes in the hippocampus, orbital frontal cortex, and parietal lobes. Regions where tissue reductions were correlated with obesity were identified using tensor-based morphometry (TBM), an advanced method for computational analysis of brain structure that measures the level of brain tissue loss or excess at high resolution between groups of subjects (Hua et al., 2008a) or over time in longitudinal studies (Ho et al., 2009a, Hua et al., 2009). Recent proton MR spectroscopy studies also showed that higher BMI was correlated with lower concentrations of a spectroscopic marker of neuronal viability in frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (Gazdzinski et al., 2008, Gazdzinski et al., 2009).

Higher body tissue adiposity is known to be related to brain atrophy in cognitively normal elderly persons (Raji et al., 2009a), so a logical extension is to see if such a relationship is also found in cognitively impaired individuals. Our prior study was limited to a sample of 94 cognitively healthy individuals from the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) (Raji et al., 2009a), so we extended the design here to a sample over seven times the size. We found that the relationship between BMI and atrophy was maintained not just in healthy elderly but even in MCI and AD, and across large independent referral-based and community-based cohorts, with difference demographics and risk factors. Jointly analyzing datasets from large independent samples is also of interest to understand how well risk factors for atrophy extend from the ADNI, which is referral-based, to more general epidemiological studies, such as the CHS. In one of the largest structural brain mapping studies ever performed, we provided new evidence for the hypothesis that higher BMI is associated with additional burden on brain structure in MCI and in early Alzheimer’s disease. Possible causes of this association include poor diet and/or poor vascular health, as well as specific susceptibility genes, such as the obesity gene FTO, which affects both body mass and the brain (Ho et al., 2009b).

To evaluate associations between BMI and brain structure, we used TBM analyses of 3-dimensional volumetric brain MRI scans from two independent cohorts: the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), and the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study (CHS-CS). By comparing results of our analyses from a population based community cohort study (CHS-CS) with those from a referral clinic based population (ADNI), we sought to amplify power and replicate our findings in independent population samples. We hypothesized that the association between BMI and brain structure would be detectable throughout the brain in both samples, after statistically controlling for any effects of age, sex, and education on brain structure.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Subjects were selected from two separate cohorts: the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (see Table 1 for demographics) and the Pittsburgh Cardiovascular Health Study- Cognition Study (CHS-CS) (whose demographics are shown in Table 2).

Table 1. Subject demographics and neuropsychiatric characteristics for the ADNI sample.

The mean ± s.d. is shown for the following variables: age, education, BMI, MMSE, and sum-of-boxes CDR.

| AD (n=188) | MCI (n=399) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 75.4±7.5* | 74.8±7.4* |

| Sex (Male) | 99 | 257 |

| Ethnicity: White | 176 | 373 |

| Black | 8 | 15 |

| Other | 4 | 11 |

| Education (>high school) | 69.7% | 80.2% |

| Presence of ApoE4 | 67.0%** | 54.6%** |

| BMI | 25.5±3.9 | 26.1±4.0 |

| MMSE | 23.3±2.0 | 27.0±1.8 |

| Sum-of-boxes CDR | 4.4±1.6 | 1.6±0.9 |

An ANOVA was performed on the variable age only to determine whether the mean age differed significantly between ADNI and CHS groups. The average age was different between ADNI and CHS groups for the AD patients (F1,222 =24.5; P=1.468 × 10−6), and for the MCI patients (F1,474=32.2; P=2.404 × 10−8).

A chi-squared test was performed for the categorical variable, presence of ApoE4; the subscript indicates the number of degrees of freedom. The incidence of the ApoE4 allele was different between ADNI and CHS groups in AD patients (χ21 = 18.8; P =1.456 × 10−5) and MCI patients (χ21=16; P =6.5 × 10−5).

Table 2. Subject demographics and neuropsychiatric characteristics for the CHS-CS.

The mean ± s.d. is shown for the following variables: age, education, BMI, MMSE, and Sum-of-boxes CDR.

| AD (n=36) | MCI (n=77) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 81.9±5.2* | 79.8±4.3* |

| Sex (Male) | 12 | 39 |

| Ethnicity: White | 27 | 61 |

| Black | 11 | 20 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Education (>high school) | 41.7% | 53.2% |

| Apoe4 | 23.30%** | 27.50%** |

| BMI | 25.5±5.1 | 26.1±4.0 |

| 3MSE | 77.7±13.3 | 90.0±6.6 |

| DSST | 26.6±12.9 | 36.3±12.4 |

An ANOVA was performed on the variable age only to determine whether the mean age differed significantly between ADNI and CHS groups. The average age was different between ADNI and CHS groups for the AD patients (F1,222 =24.5; P=1.468 × 10−6), and for the MCI patients (F1,474=32.2; P=2.404 × 10−8).

A chi-squared test was performed for the categorical variable, presence of ApoE4; the subscript indicates the number of degrees of freedom. The incidence of the ApoE4 allele was different between ADNI and CHS groups in AD patients (χ21 = 18.8; P =1.456 × 10−5) and MCI patients (χ21=15.9; P =6.5 × 10−5).

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)

The ADNI is a study launched in 2004 by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), private pharmaceutical companies, and non-profit organizations, as a 5-year public-private partnership (Mueller et al., 2005a, Mueller et al., 2005b). The goal of ADNI is to determine biological markers of Alzheimer’s disease through neuroimaging, genetics, neuropsychological tests and other measures, to develop new treatments and monitor their effectiveness, and lessen the time of clinical trials. Subjects were recruited from 58 sites in the United States. The study was conducted according to the Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and U.S. 21 CFR Part 50 – Protection of Human Subjects, and Part 56 – Institutional Review Boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before protocol-specific procedures were performed. All data acquired as part of this study are publicly available (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/).

The ADNI subjects in this study met the following criteria: (1) baseline scans were available on the ADNI public database (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Data/) on June 25, 2009 (the date of download), and (2) had height and weight measurements taken at the time of the baseline scan, and (3) diagnosed as AD or MCI based on clinical and cognitive exams at time of baseline scan. Of the 823 ADNI subjects available, 587 (MCI, N=399, 74.8±7.4 years; AD, N=188, 75.4±7.5 years) met the inclusion criteria for our study described above (Table 1). All subjects underwent clinical and cognitive evaluations at the time of their MRI scan, including the clinical dementia rating (CDR) and the mini-mental state examination (MMSE). Average sum-of-boxes CDR and MMSE scores for each diagnostic group are shown in Table 1. The sum-of-boxes clinical dementia rating (CDR-SB), ranging from 0 to 18, measures dementia severity by evaluating patients’ performance in six domains: memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care (Berg 1988, Hughes et al., 1982, Morris 1993). The MMSE, with scores ranging from 0 to 30, is a global measure of mental status based on five cognitive domains: orientation registration, attention and calculation, recall, and language (Cockrell and Folstein 1988, Folstein et al., 1975). Scores below 24 are typically associated with dementia. All AD patients met NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD (McKhann et al., 1984). On average, AD patients in this study were considered to have mild to moderate - but not severe - Alzheimer’s disease, with mean baseline MMSE scores of 23.3±2.0SD and mean sum-of-boxes CDR scores of 4.4±1.6SD. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the ADNI protocol (Mueller et al., 2005a, Mueller et al., 2005b).

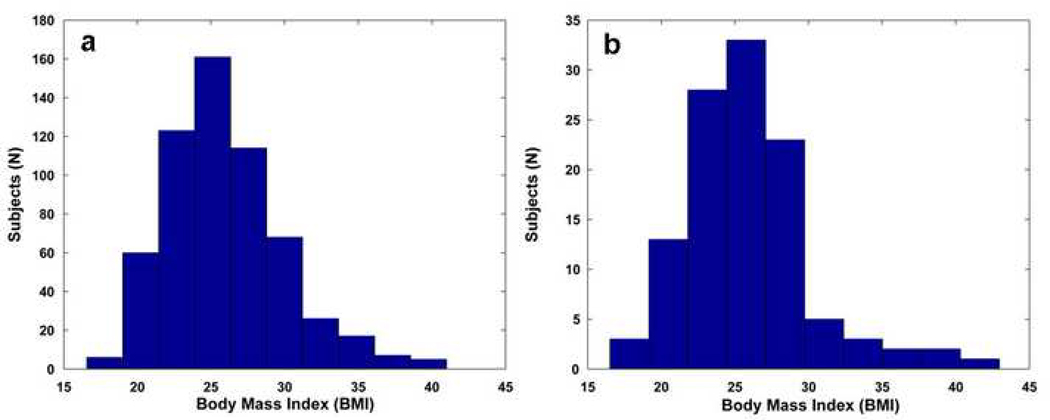

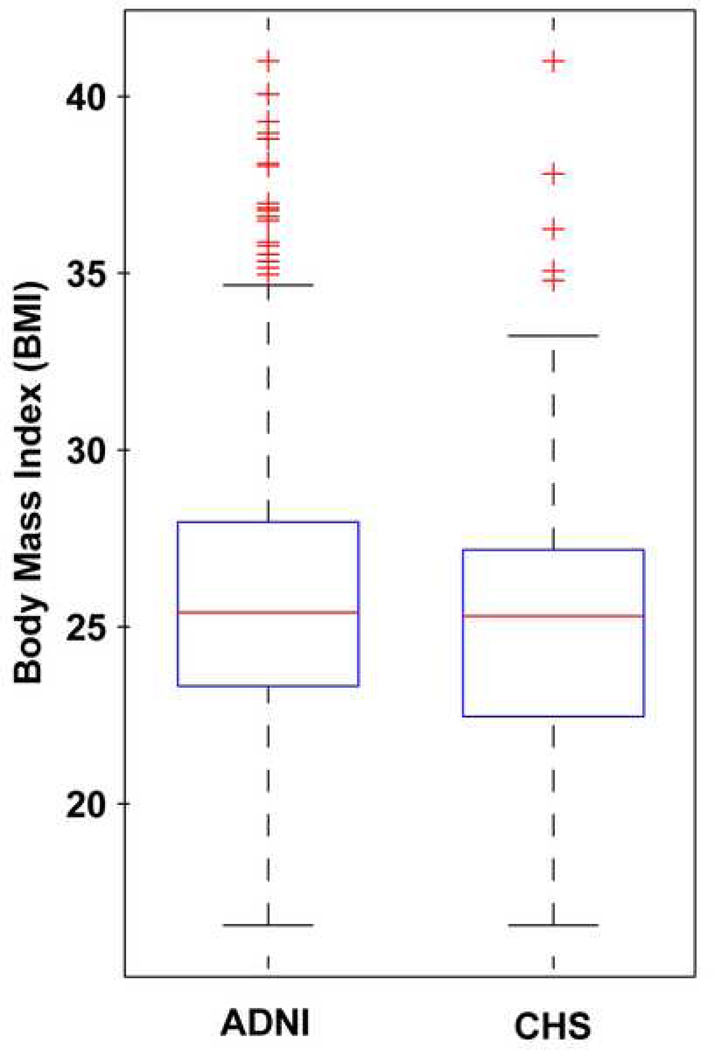

All ADNI subjects (N=587) examined in this study had weight (pounds or kilograms) and height (inches or centimeters) measurements taken during a physical exam at the time of their baseline MRI scan. All values were converted to weight (pounds) and height (inches) and BMI was computed using the following formula: weight (lb) × 703 / [height (in)]2, using a constant to account for the unit conversion. Since the distribution of BMI is slightly skewed (see histogram, Figure 1) due to the outliers which tend to be above the mean more commonly than below it (see box plot, Figure 2), we categorized the data into quartiles. By doing this, the outliers at the high end of the BMI distribution do not have undue influence and are aggregated into the highest quartile, which is then treated as a category. The association between brain atrophy and BMI was still found after binning the subjects into quartiles based on their BMI (ADNI, critical uncorrected P-value=0.022; CHS, critical uncorrected P-value=0.012). We also analyzed the data excluding outliers, shown as BMI values greater than 99.3% (Figure 2: N=17, for ADNI; N=5, for CHS) (ADNI, critical uncorrected P-value=0.024; CHS, critical uncorrected P-value=0.010) and found that all maps of associations between BMI and atrophy remained statistically significant (ADNI, critical uncorrected P-value=0.024; CHS, critical uncorrected P-value=0.010).

Figure 1.

Histogram of body mass index (BMI) values from (a) ADNI and (b) CHS cohorts.

Figure 2.

Box plot of body mass index (BMI) values from ADNI and CHS cohorts. In this type of plot, the bottom and top of the boxes show the 25th and 75th percentiles of the data (lower and upper quartiles); the band near the middle of each box shows the median (50th percentile). From the plot, the outliers are shown as observations that extend beyond the whiskers.

The Pittsburgh Cardiovascular Health Study- Cognition Study (CHS-CS)

The CHS-CS was designed to determine the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in 1998–1999 in a population of subjects identified as normal or MCI in 1991–1994 (Lopez et al., 2003). Details of the CHS design have been described previously (Fried et al., 1991, Tell et al., 1993). Briefly, subjects were recruited from a Medicare database and were eligible if they were over age 65, ambulatory, and non-institutionalized. In 1998–1999, 456 subjects had completed neurological and neuropsychological examinations and were scanned with 3D volumetric brain MRI (Raji et al., 2009b). We used MRI scans from 1998–1999 since subjects at 1989–1990 and 1992–1993 were scanned with low-resolution MRI. In 1998–1999, 116 subjects were diagnosed with AD or MCI. Of these, we analyzed 113 subjects that met the following criteria: diagnosed with either MCI (N=77; 79.8±4.3 years) or AD (N=36; 81.9±5.2 years), and had a high-resolution MRI scan and body mass index measurements taken in 1998–99 (Table 2, Figures 1,2).

Diagnosis of MCI and dementia were based on neuropsychological, psychiatric and neurological assessments described in detail here (Lopez et al., 2003). All subjects underwent extensive neuropsychiatric examinations including Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MSE) (Cockrell and Folstein 1988, Folstein et al., 1975) and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) (Salthouse 1978) with scores less than 80 or 78 being classified as possible prevalent dementia (Kuller et al., 1998). The 3MSE and DSST were not used for diagnosis or as part of a two-step diagnostic process; however these scores are included in Table 2 to show range of cognitive function in MCI and AD patient groups. The diagnosis of MCI and AD was made by an adjudication committee after reviewing the neuropsychological battery, neurological, and clinical data.

Education

The number of years of education completed was accounted for and subjects were categorized into two groups: those who completed more than 12 years of education (more than high school) or those who completed 12 or fewer years (see Table 1 and 2). Data on educational level was not recorded in exactly the same way for both cohorts (ADNI and CHS). For example, educational level in the CHS cohort was categorized into the following groups: completion of some high school (less than 12 years), completed high school (12 years), received GED (General Educational Development credential; 13 years), some college (14 years), completed college (15 years), or completed some professional school (16 years). In the ADNI, data on educational level was based on the number of years of education completed. To remain consistent in our replication analyses, we treated education as a dichotomous variable (“0” for those who did not complete high school, and “1” for those who did complete high school), to avoid using the different educational level variables, and to use a common measure that could be derived from the available data on both cohorts.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) subtypes

The MCI amnestic subtype carries greatest risk for imminent conversion to AD and is defined by the following: subjective memory problems, objective memory impairment for age, preserved general cognitive function, intact functional activities, and not demented (Petersen 2004). The MCI subjects (N=399) in the ADNI cohort are all considered as amnestic MCI (Mueller et al., 2005b). In the CHS cohort, the MCI amnestic subtype was less frequent with probable amnestic (N=9, or 8.0%) and possible amnestic (N=7, 6.2%). The total number of possible and probable CHS subjects with the amnestic MCI subtype was 16 out of 113 (or 14.2%). The neuropsychological characteristics of MCI subgroups have been identified in the CHS (Lopez et al., 2006). Since we analyzed data from two completely different types of cohorts, ADNI (referral-based) and CHS (community-based), the prevalence of amnestic MCI subtype was expected to be different (see Discussion for more details).

2.2. MRI acquisition and image correction

All ADNI subjects were scanned at multiple ADNI sites according to a standardized protocol developed after a major effort to evaluate 3D T1-weighted sequences for morphometric analyses (Jack et al., 2008). High-resolution structural brain MRI scans were acquired, in ADNI, using 1.5 and 3 Tesla MRI scanners; however, since the majority of subjects were scanned at 1.5 T, and to avoid any potentially confounding effect of scanner field strength on tissue volume quantification, which we examined in (Ho et al., 2009a), we restricted our analysis to 1.5 T MRI scans.

In the 1.5T scanning protocol, each subject underwent two 1.5 T T1-weighted MRI scans using a 3D sagittal volumetric magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) sequence. As described in (Jack et al., 2008), typical 1.5T acquisition parameters are repetition time (TR) of 2400 ms, minimum full TE, inversion time (TI) of 1000 ms, flip angle 8°, 24 cm field of view, with a 256×256×170 acquisition matrix in the x-, y-, and z-dimensions yielding a voxel size of 1.25×1.25×1.2 mm3. In-plane, zero-filled reconstruction yielded a 256×256 matrix for a reconstructed voxel size of 0.9375×0.9375×1.2 mm3. In plane, zero-filled reconstruction yielded a 256×256 matrix for a reconstructed voxel size of 1.0×1.0×1.2 mm3. To ensure consistency among scans from acquired at different sites, all images were calibrated with phantom-based geometric corrections (Gunter et al., 2006).

Additional image corrections were also applied, using a processing pipeline at the Mayo Clinic, consisting of: (1) a procedure termed GradWarp to correct geometric distortion due to gradient non-linearity (Jovicich et al., 2006), (2) a “B1-correction”, to adjust for image intensity inhomogeneity due to B1 non-uniformity using calibration scans (Jack et al., 2008), (3) “N3” bias field correction, for reducing residual intensity inhomogeneity (Sled et al., 1998), and (4) geometrical scaling, according to a phantom scan acquired for each subject (Jack et al., 2008), to adjust for scanner- and session-specific calibration errors. In addition to the original uncorrected image files, images with all of these corrections already applied (GradWarp, B1, phantom scaling, and N3) are available to the general scientific community (at www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI).

All CHS-CS MRI data were acquired at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center MR Research Center using a 1.5 T GE Signa scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, LX Version). A 3D volumetric spoiled gradient recalled acquisition (SPGR) sequence was obtained covering the whole brain (TE/TR = 5/25 msec, flip angle = 40°, NEX = 1, slice thickness = 1.5 mm/0 mm interslice gap). Images were acquired parallel to the AC-PC line, with an in-plane acquisition matrix of 256×256×124 image elements, 250 × 250 mm field of view and an in-plane voxel size of 0.98 mm3.

2.3 Image pre-processing

Image prep-processing steps have been described in previous studies (Ho et al., 2009a, Raji et al., 2009a). Briefly, all scans were corrected for intensity non-uniformities and linearly registered to the International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM-53) (Mazziotta et al., 2001) standard brain image template using a nine-parameter registration to account for global position and scale differences across individuals, including head size (Hua et al., 2008a). Globally aligned images were re-sampled in an isotropic space of 220 voxels along each axis (x, y, and z) with a final voxel size of 1 mm3.

2.4 Tensor-based morphometry (TBM) and 3D Jacobian maps

For each cohort, an ‘average’ brain image, was constructed using MRI scans of 40 cognitively normal subjects to enable automated image registration, reduce statistical bias, and to make statistically significant effects easier to detect (Hua et al., 2008a, Hua et al., 2008b, Kochunov et al., 2001). A study-specific template was created using 40 cognitively normal individuals from the ADNI database and a separate template was created using 40 subjects from the CHS sample. Both templates were age and sex matched according to their corresponding sample population. All scans were non-linearly aligned to their own study-specific template so that each cohort would share a common coordinate system. The local expansion factor of the 3D elastic warping transform, known as the Jacobian determinant, was plotted for each subject (Leow et al., 2005). These 3D Jacobian maps show relative volume differences between each individual and the common template, and reveal areas of structural volume deficits, or expansions (e.g., in the ventricles), relative to the healthy population average.

2.5. Correlations of structural brain differences with BMI

As in our prior work (Ho et al., 2009b), associations between BMI and brain structure were examined by fitting a standard multiple regression model to the data at each voxel, of the form:

| [1] |

As is standard in statistical brain mapping, a separate regression equation was fitted to the data at different voxels. At any specific voxel, the dependent variable, y, is the vector whose components represent the determinant of the Jacobian matrix of deformation at that particular voxel (a measure of regional brain volume). The independent measure, x1, is a vector whose components represent the BMI across subjects, x2 is a vector representing the age of each subject, x3 is a vector representing the sex of each subject, and ε is an error term. This regression is conducted at each voxel in the brain to determine the association of BMI with structural differences, in the subject sample, across the entire brain. Using the general linear model, a p-value map can be made for each regression coefficient, showing the significance of its fit to the data at each voxel.

At each voxel, partial correlations were computed between the Jacobian values (which represent brain tissue deficit or excess relative to the standard template) and body mass index (BMI) at baseline, controlling for age, sex and education. All correlation maps were corrected for multiple comparisons using the widely-used false discovery rate (FDR) method (Benjamini 1995). The false discovery rate (FDR) method decides whether a threshold can be assigned to the statistical map (of correlations) that keeps the expected false discovery rate below 5% (i.e., no more than 5% of the voxels are false positive findings). This threshold is based on the expected proportion of voxels with statistics exceeding any given threshold under the null hypothesis (Benjamini 1995).

The covariates (age, sex, and education) were chosen for theoretical reasons, based on a prior hypothesis that they would have an effect, rather than just testing a large number of measures and retaining only the ones that gave a good fit to the empirical data. Age, sex, and years of education were controlled for in the regression analysis as these variables have previously been found to correlate with individual differences in brain volume previously in independent samples of younger adults (Brun et al., 2009, Luders et al., 2009a). While we tested the correlations with and without the covariates, we have reported the critical uncorrected P-values and beta maps that have been controlled for age, sex, and education. It is best to show the results after adjusting these factors, as these variables are known from prior studies to be somewhat correlated with individual differences in brain volume (Brun et al., 2009, Luders et al., 2009a).

3. Results

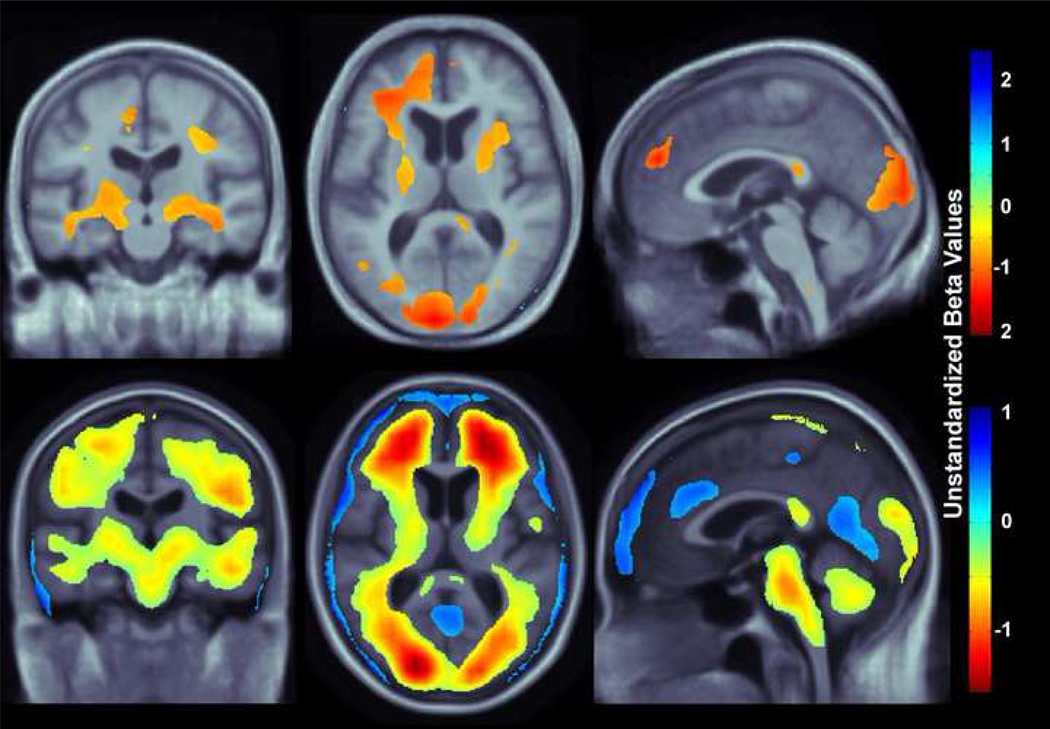

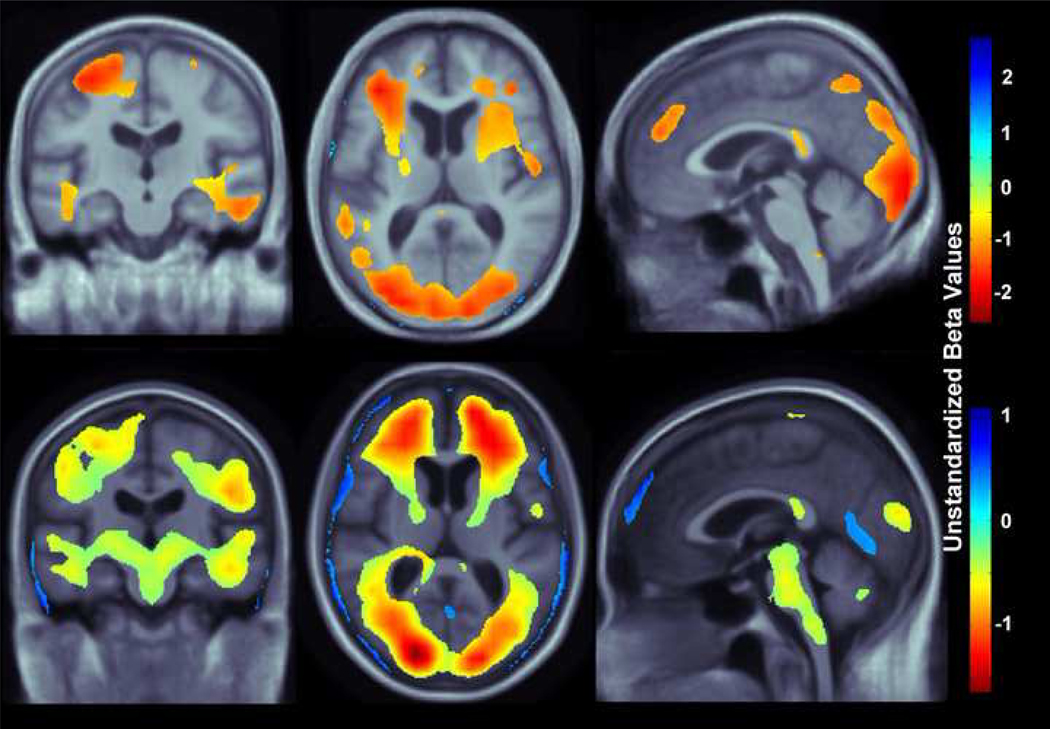

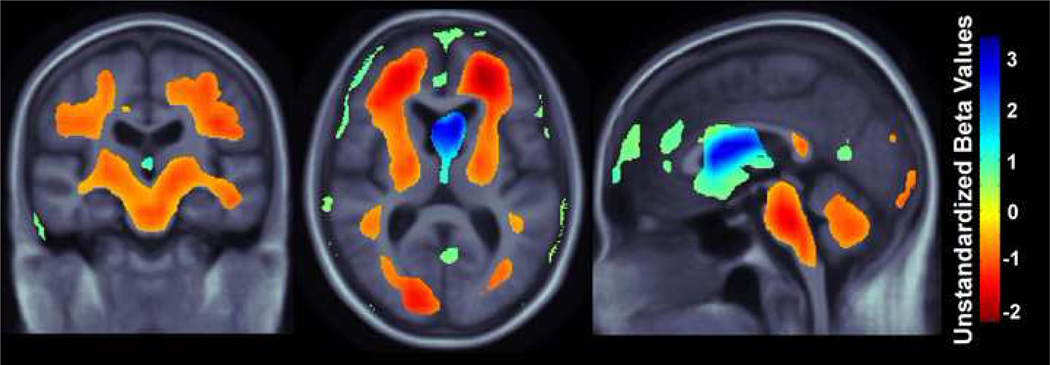

Our study had three main findings: (1) higher BMI was associated with lower brain volumes (Figure 3) in a combined group of patients diagnosed with MCI or AD replicated in two independent cohorts, ADNI and CHS, (2) affected areas included the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobe regions in two separate elderly cohorts (Figures 3,4), and (3) in AD but not MCI, ventricular expansion was also associated with higher BMI (Figure 5), but this effect was only found in the ADNI cohort, not in the CHS cohort (the high sample sizes with ADNI gave higher power).

Figure 3.

3D maps show areas where regional brain tissue volumes were significantly associated with BMI in AD and MCI subjects (pooled together) from the CHS and ADNI cohorts (N=700). In the significant areas, the regression coefficients (unstandardized beta values) are shown at each voxel for the CHS subjects (top row; N=113, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.0062) and ADNI subjects (bottom row; N=587, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.025). These represent the estimated degree of tissue excess or deficit at each voxel, as a percentage, for every unit increase in BMI, after statistically controlling for effects age, sex, and education on brain structure. They can be considered as the slope of best fitting line relating tissue deficits to BMI. Images are in radiological convention (left side of the brain shown on the right) and are displayed on a specially constructed average brain template created from the subjects within each cohort (mean deformation template, MDT).

Figure 4.

3D maps show areas where regional brain tissue volumes were significantly associated with BMI in MCI subjects in the CHS cohort (top row; N=77; critical uncorrected P-value: 0.0093) and ADNI cohort (bottom row; N=400, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.018). These represent the estimated degree of tissue excess or deficit at each voxel, as a percentage, for every unit increase in BMI, after statistically controlling for effects age, sex, and education on brain structure. Images are in radiological convention (left side of the brain shown on the right) and are displayed on a specially constructed average brain template created from the subjects within each cohort (mean deformation template, or MDT).

Figure 5.

3D maps show areas where regional brain tissue volumes were significantly associated with BMI in AD subjects only in the ADNI cohort (N=188, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.012). 3D maps for the CHS cohort did not pass FDR and are therefore not displayed. These represent the estimated degree of tissue excess or deficit at each voxel, as a percentage, for every unit increase in BMI, after statistically controlling for effects age, sex, and education on brain structure. Images are in radiological convention (left side of the brain shown on the right) and are displayed on a specially constructed average brain template created from the subjects within each cohort (mean deformation template, or MDT).

In a whole brain analysis, every unit increase in BMI was associated with a 0.5–1.5% average brain tissue reduction (depending on the brain region) after controlling for age, sex, and education in a pooled sample of all MCI and AD patients from the CHS-CS and ADNI cohorts (Figure 3; CHS, N=113, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.006; ADNI, N=587, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.025). We used a standard false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple statistical comparisons across voxels in the brain, at the conventionally accepted level of q=0.05; this means that only 5% of the voxels shown in the thresholded statistical maps are expected to be false positives. Regression coefficient (unstandardized beta) maps are shown only for statistically significant regions, representing an estimate of the average percent brain tissue decrease for each unit increase in BMI. Warmer colors (orange and red) represent regions where every unit increase in BMI is associated with an average 1.0–1.5% reduction in brain tissue. The ADNI sample (N=587) is about 5 times larger than the CHS sample (N=113). The unstandardized beta value scales for each cohort are slightly different (Figure 3), but as unstandardized beta values are measures of effect size, they should remain somewhat stable as the sample size is increased. Yellow colors, shown in the ADNI whole brain maps (Figure 3, bottom panel) suggest that there is a roughly 0.5% decrease in brain tissue (locally) for every unit increase in BMI. Blue colors, displayed only in the ADNI whole brain maps (Figure 3, bottom panel) are found in CSF regions, and these effects are likely attributable to ventricular expansion or expansion of the interhemispheric fissure and other sulcal spaces (as seen in past studies, e.g., Hua et al., 2008). The frontal, temporal, and occipital, and to a lesser extent the parietal lobes show associations in both CHS and ADNI cohorts, with a more restricted pattern of associations with brain atrophy observed in the CHS sample. Additionally, the brainstem and cerebellum are associated with a 0.5% brain volume deficit per unit BMI increase in the ADNI cohort but associations in those regions are not detected in the CHS cohort (perhaps due to the smaller sample size).

To further investigate if BMI shows different patterns of association with brain volumetric deficits in MCI and AD, correlations were computed between BMI and Jacobian values in a whole brain analysis in subjects diagnosed with MCI only (Figure 4; CHS, N=77, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.009; ADNI, N=400, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.018). After controlling for age, sex, and education, every unit increase in BMI was associated with approximately 1–2% average brain tissue reduction in the CHS sample and 0.5–1.5% average brain tissue decrease in the ADNI sample. Again, the distribution of regions where associations were detected is more widespread in the ADNI compared to the CHS sample; however, the sample sizes differ by a factor of five, boosting ADNI’s power to detect brain regions whose volumes are significantly associated with BMI. Similar brain areas, including the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes are affected in the MCI group when compared to the atrophy pattern observed in the combined MCI and AD group; however, the pattern of decreased brain volume is more restricted in the MCI-only group. Again, the brainstem is a region showing detectable associations with BMI in the ADNI group, but these effects are undetected (or not present) in the (smaller) CHS cohort.

Patients with AD had widespread brain volume deficits and ventricular expansion associated with increased BMI (Figure 5. ADNI, N=188, critical uncorrected P-value: 0.012) in a comparable pattern to the associations observed in the MCI patients (Figure 4). After controlling for age, sex, and education, every unit increase in BMI was associated with approximately 1–2% average brain tissue reduction in the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes, brainstem, and cerebellum, shown in orange and red colors. Blue colors represent approximately a 3% expansion, associated with every unit increase in BMI, observed only in the ventricles of AD patients. 3D maps, correlating BMI and Jacobian values, in the CHS cohort (N=36) did not pass FDR correction, most likely due to limited sample size and lack of power, and are therefore not shown.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to use two separate cohorts to show that higher body tissue adiposity is correlated with brain atrophy in patients diagnosed with MCI and AD. These correlations are still found within diagnostic groups, and they persist after adjusting for other factors that influence brain volumes or brain atrophy, such as age, sex, and education. Many of the affected brain regions are responsible for cognitive function, such as the hippocampus and frontal lobes, and are consistent with regions identified in prior work that focused only on healthy subjects (Gazdzinski et al., 2008, Gazdzinski et al., 2009, Raji et al., 2009a). These findings were generated in a pooled sample of MCI and AD subjects (Figure 3) but also held when the MCI (Figure 4) and AD (Figure 5) subjects were analyzed separately. The lack of statistically significant findings in the CHS-CS AD subjects may just reflect the relatively smaller sample size in that group (N=36) compared to the number of ADNI AD subjects (N=188).

Prior work has also suggested that the amount of adipose tissue in the body can modify the metabolism of beta-amyloid, thus increasing risk for AD (Moroz et al., 2008). Obesity can also raise risk for vascular diseases such as hypertension and type II diabetes mellitus that themselves can induce deficits in brain structure and function (Dai et al., 2008, Iadecola 2004, Watson et al., 2003). Even so, associations between brain structure and BMI persist even after adjusting for the presence of diabetes (DM2) and for fasting plasma insulin levels (Raji et al., 2009). All these studies suggest that obesity can modify risk for AD through at least several mechanisms.

Even though a fairly consistent pattern of brain atrophy associated with obesity was observed in both ADNI and CHS samples, several key brain regions linked with higher BMI in the ADNI subjects but were not detected in the CHS subjects. In MCI and AD subjects scanned as a part of ADNI, higher BMI was correlated with lower brain tissue in more broadly distributed regions including the cerebellum and brainstem (i.e., pons, midbrain, and upper part of the medulla; Figure 3,4). Further, CSF expansion - an indication of lower brain volume in adjacent brain regions - was also observed in the ADNI group. These differences could be attributed to the sample size difference between the ADNI (N=587) and CHS (N=113) groups. A 5-fold increase in sample size greatly increases the power to detect a more broadly distributed pattern of brain atrophy in the ADNI sample that may go undetected in the smaller CHS sample.

In the MCI subjects, BMI is significantly correlated with volume variation in brain regions that do not completely overlap in the CHS (Figure 4, top row) and the ADNI cohorts (Figure 4, bottom row). This difference could be attributed to the percentage of amnestic MCI subjects present in the ADNI (100%) versus the CHS (8%, probable amnestic MCI; 6.2% possible amnestic MCI) groups. A previous CHS study analyzing MCI subjects found greater volume deficits in the hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior temporal, and parietal cortices of amnestic MCI subjects compared to MCI subjects without memory impairments (Lopez et al., 2006). Thus, these structural brain differences in amnestic versus non-amnestic MCI subtypes may affect the strength and location of correlations between brain structure and BMI. In ADNI, there is more widespread atrophy overall compared to the CHS group. The brainstem does not show detectable atrophy in the CHS group, but is shown to be a brain region whose volume is negatively associated with BMI. Even so, similar brain areas, including frontal, temporal, and occipital lobe regions, were correlated with BMI in both ADNI and CHS populations.

Another possibility is that the differences in the subject demographics of each cohort are contributing to the differences in these ADNI and CHS brain maps (Figures 3,4), even after controlling for effects of age, sex, and education on brain structure. For example, the AD patients are, on average, younger in the ADNI group than the CHS group (ADNI=75.4±7.5 versus CHS=81.9±5.2 years; F1,222=24.5, P-value=1.47 × 10−6). Similarly, MCI patients are also younger in ADNI (ADNI=74.8±7.4 versus CHS=79.8±4.3 years; F1,474=32.2, P-value=2.40 × 10−8). The effect of age on brain structure was corrected for in our analysis; however, the overall age difference between the ADNI and CHS groups may be an indication that the referral-based cohort, ADNI, may include subjects with more severe symptoms of AD at an earlier age.

Both samples in this study were predominantly Caucasian, so care must be exercised in generalizing the findings to other ethnic groups. There are known ethnic differences in the prevalence of known risk genes for obesity, including a commonly carried variant in the FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated) gene. For example, 51% of Yorubans (West African natives), 46% of Western and Central Europeans, and only 16% of Chinese carry the “adverse” FTO allele that is associated with a higher BMI (Frazer et al., 2007). Further, the prevalence of AD and other dementias is about two times higher in African-Americans than in elderly whites of the same age group, according to the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS) (Plassman et al., 2007). Another study showed that Hispanics were two and half times more likely than whites of the same age and sex to have AD and other dementias (Gurland et al., 1999). Other conditions including high lood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, and stroke have been shown to increase the risk for AD (Luchsinger et al., 2005), and these tend to be more common in African-Americans and Hispanics (Langa et al., 2006). The 2006 Health and Retirement Study showed that high blood pressure and diabetes tended to be more common in African-Americans and Hispanics than in whites, but heart disease was more common in whites than in African-American and Hispanic groups (Langa et al., 2006). Thus, consideration of ethnic and racial differences is critical to a complete understanding of how obesity influences brain structure and risk for cognitive impairment and AD.

Prior studies report mixed findings regarding how the BMI-brain structure association may be influenced by sex differences. One study found a correlation between BMI and cerebral volume atrophy in Japanese men but not women (Taki et al., 2008), but another study of Swedish women showed substantial temporal lobe atrophy (Gustafson et al., 2004). Another CHS study did not detect a sex difference in BMI-related brain atrophy in 94 elderly cognitively healthy subjects (Raji et al., 2009a). These past studies focus on non-demented populations, so further study is needed on the effect of sex differences in MCI and AD subjects. In our study, we controlled for the effects of sex differences in brain structure by including sex as a covariate in our model; however, BMI by sex interactions may be detectable in future studies.

Our referral-based and community-based cohorts differ in several ways, including the percentage of subjects carrying the ApoE4 risk gene for Alzheimer’s disease. The % of patients carrying the ApoE4 genetic variant is much higher in the ADNI study compared to CHS for both the AD (ADNI=67.0% versus CHS=23.3%; X21 = 18.8, P-value=1.5 × 10−5) and MCI groups (ADNI=54.6% versus CHS=27.5%; X21 = 16.0, P-value= 6.5 × 10−5). Again, the higher % of subjects carrying the ApoE4 variant in the referral-based group supports the notion that ADNI subjects may experience more severe symptoms compared to their CHS counterparts. Prior ADNI studies found greater hippocampal (Schuff et al., 2009) and temporal lobe atrophy in ApoE4 carriers versus non-carriers (Hua et al., 2008b). Even after accounting for the presence of the ApoE4 allele, in addition to the effects of age, sex, and education, BMI was still correlated with lower regional brain volumes (ADNI: critical uncorrected P-value=0.025; CHS: critical uncorrected P-value= 0.004).

Some prior studies have reported low late-life BMI and rapid weight loss in patients with dementia (Fitzpatrick et al., 2009), yet our results provide evidence that higher BMI is associated with lower brain volumes, even in MCI (Figure 4) and AD (Figure 5). Intriguingly, with higher BMI, our AD group showed not only lower brain volumes, but also ventricular expansion – a further indicator of brain matter loss. One interpretation of these cross-sectional findings is that more rapid weight loss, and thus a lower BMI, tends to occur in the later stages of dementia, but the present results show brain structure differences resulting from a lifetime of high BMI. As a result, one might expect the relationship between brain volumes and BMI would change in degree if not in kind from early AD to late AD, depending on whether weight loss due to the disease becomes dominant. Another possibility, and a limitation to using BMI as a measure of obesity, is that conventional adiposity measures may not capture changes in lean body mass and adipose tissue related to the aging process (Stevens et al., 1999). Waist circumference and waist to hip ratio have been argued to be better measurements of adiposity, but these were not available for both the ADNI and CHS datasets.

There are, however, several caveats to consider in this work. Our study relates body mass index to brain atrophy in persons who are relatively early in the course of their cognitive decline. These results would not apply to persons in very advanced states in dementia, for whom lack of adequate food intake is often a major predictor of mortality (Franzoni et al., 1996). Rather, our work is best applied from the standpoint of understanding how control of body weight and other lifestyle factors may promote healthy brain aging and reduce the partly preventable risks for cognitive impairment and dementia.

One notable aspect of the topography of brain matter loss in Figures 3–5 is that the atrophy associated with BMI appears to lie in the white matter rather than the cortical surface. This is mainly because (1) the registration fields in TBM are spatially smooth and partial volume averaging effects diminish the signal somewhat at tissue boundaries, such as the cortex/CSF interface, and (2) the registration accuracy of TBM is poorer at the cortical surface, at least relative to some approaches designed to explicitly model the cortical surface, and align cortical regions (Lepore et al., 2010, Thompson et al., 2004).

As noted in prior work (Hua et al., 2008b, Leow et al., 2009), to better sensitize the TBM approach for detecting cortical gray matter loss, several approaches have been considered: (1) use of voxel-based morphometry (VBM) (Ashburner and Friston 2000) or a related approach termed RAVENS (Davatzikos et al., 2001), (2) adaptively smooth deformation-based compression signals at each point based on the amount of gray matter lying under the filter kernel (Studholme et al., 2003), or (3) run deformation maps at a very high spatial resolution and with less spatial regularization or with a regularization term that enforces continuity but not smoothness (Leow et al., 2005). In general, however, cortical differences in AD are better studied using cortical modeling methods that explicitly match cortical landmarks, although studies are more labor-intensive to perform (Thompson et al., 2003, Thompson et al., 2001).

There remain, however, several key implications from this work. First, body tissue adiposity is independently linked to brain atrophy in cognitively impaired persons with MCI or AD. Second, this is evident in both a community cohort study and a referral clinic population – highlighting that the relationship is reproducible. Third, the strength of the BMI-brain atrophy relationship throughout the spectrum of normal cognition, MCI, and AD underscores the need to consider being overweight and obese as modifying the risk for cognitive impairment because of the link to compromised brain structure. An extended clinical possibility arising from this line of work is that controlling body fat content even in late life may reduce risk for dementia – though this will ultimately only be tested in randomized clinical trials, or interventional studies with a longitudinal component.

Methodologically, this study pools data across cohorts to improve the reproducibility and reliability of the findings. Future studies could benefit from this data-sharing approach in much the same way genomic studies pool data across different cohorts (Thompson and Martin 2010).

The present data have a number of interesting applications. One is derived from the field of cognitive epidemiology - a relatively new field of study that examines intelligence-health associations (Deary 2009). In our current study, Tables 1,2 show that there is a difference in educational level for MCI and AD in both the ADNI (χ21=79.2; P=2.2×10−16) and CHS (χ21=4.0; P=0.05) cohorts, with the AD group having a smaller percentage of subjects with more than 12 years of education. This could suggest a hypothetical causal chain whereby a lower educational level is associated with poorer skills for choosing healthy behaviors leading to higher BMI values and lower brain volumes. Clearly, whether or not an individual chooses healthy behaviors depends on many factors – including access to exercise, education, and other cultural factors. General intelligence may also be a contributing factor.

Specifically, general intelligence has been found to contribute to overall educational achievement (Deary et al., 2007). It is unfortunate that a measure of intelligence was not consistently collected in both the datasets analyzed here, as intelligence is the best single predictor of achieved educational level (Deary et al., 2007). This hypothetical causal chain could show that poorer intellectual function leads to a lower level of educational attainment, which may be associated with poorer skills for choosing healthy behaviors, higher BMI values, and thus lower brain volumes. Interestingly, intelligence is itself positively correlated with brain volume (Luders et al., 2009b, McDaniel 2005).

If this line of reasoning is correct, cognitive epidemiology may provide some insight for public policy (Lubinski 2009). We have shown that obesity may modify the risk for cognitive impairment because of the link to compromised brain structure. Thus, when proposing behaviors for controlling body fat content, the population distribution of intelligence should also be considered as the relationship between general intelligence and healthy outcomes has been established (Arden et al., 2009, Lubinski 2009). Preventing obesity requires healthy behaviors that may already be more evident in better educated people, so healthcare systems may have greater success by developing targeting messages to populations with poorer access to education, or poorer educational attainment.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Abbott, AstraZeneca AB, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai Global Clinical Development, Elan Corporation, Genentech, GE Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Innogenetics, Johnson and Johnson, Eli Lilly and Co., Medpace, Inc., Merck and Co., Inc., Novartis AG, Pfizer Inc, F. Hoffman-La Roche, Schering-Plough, Synarc, Inc., and Wyeth, as well as non-profit partners the Alzheimer's Association and Administration. Private sector contributions to ADNI are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org <http://www.fnih.org>). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles. This research was also supported by NIH grants P30 AG010129, K01 AG030514, and the Dana Foundation.

Algorithm development and image analysis for this study was funded by grants to P.T. from the NIBIB (R01 EB007813, R01 EB008281, R01 EB008432), NICHD (R01 HD050735), and NIA (R01 AG020098), and National Institutes of Health through the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, Grants U54-RR021813 (CCB) (to AWT and PT).

The study reported in this article was supported, in part, by funds from the National Institute of Aging to O.L.L. (AG 20098, AG05133) and L.K. (AG15928), and by contract numbers N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133, grant number U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions may be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm.

This study was also funded by an American Heart Association Pre-doctoral Grant to C.A.R. (0815465D), and by NITP (Neuroimaging Training Program), ARCS, and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program funding to A.J.H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data used in this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative database (www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI). Investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. For a complete listing of ADNI investigators, see http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Collaboration/ADNI_Manuscript_Citations.pdf.

The authors have no competing financial or other interests that might have affected this research.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no potential financial or personal conflicts of interest including relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the work submitted that could inappropriately influence this work.

References

- Arden R, Gottfredson L, Miller G. Does a fitness factor conribute to the association between inteligence and health outcomes? Evidence from medical abnormality counts among 3,654 US Veterans. Intelligence. 2009;37:581–591. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry--the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11(6 Pt 1):805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlett HL, Puhl SM, Hodgson JL, Buskirk ER. Fat-free mass in relation to stature: ratios of fat-free mass to height in children, adults, and elderly subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(5):1112–1116. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.5.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. JR Statist Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berg L. Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun CC, Lepore N, Luders E, Chou YY, Madsen SK, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Sex differences in brain structure in auditory and cingulate regions. Neuroreport. 2009;20(10):930–935. doi: 10.1097/wnr.0b013e32832c5e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Shah RC, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Change in body mass index and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65(6):892–897. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176061.33817.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockrell JR, Folstein MF. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Lopez OL, Carmichael OT, Becker JT, Kuller LH, Gach HM. Abnormal regional cerebral blood flow in cognitively normal elderly subjects with hypertension. Stroke. 2008;39(2):349–354. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.495457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davatzikos C, Genc A, Xu D, Resnick SM. Voxel-based morphometry using the RAVENS maps: methods and validation using simulated longitudinal atrophy. Neuroimage. 2001;14(6):1361–1369. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary I. Introduction to the special issue on cognitive epidemiology. Intelligence. 2009;37:517–519. [Google Scholar]

- Deary I, Strand S, Smith P, Fernandes C. Intelligence and educational achievement. Intelligence. 2007;35:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Eknoyan G. Adolphe Quetelet (1796–1874)--the average man and indices of obesity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(1):47–51. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias MF, Elias PK, Sullivan LM, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB. Lower cognitive function in the presence of obesity and hypertension: the Framingham heart study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(2):260–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.802225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Diehr P, O'Meara ES, Longstreth WT, Jr, Luchsinger JA. Midlife and late-life obesity and the risk of dementia: cardiovascular health study. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(3):336–342. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzoni S, Frisoni GB, Boffelli S, Rozzini R, Trabucchi M. Good nutritional oral intake is associated with equal survival in demented and nondemented very old patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(11):1366–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Stuve LL, Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Boudreau A, Hardenbol P, Leal SM, Pasternak S, Wheeler DA, Willis TD, Yu F, Yang H, Zeng C, Gao Y, Hu H, Hu W, Li C, Lin W, Liu S, Pan H, Tang X, Wang J, Wang W, Yu J, Zhang B, Zhang Q, Zhao H, Zhao H, Zhou J, Gabriel SB, Barry R, Blumenstiel B, Camargo A, Defelice M, Faggart M, Goyette M, Gupta S, Moore J, Nguyen H, Onofrio RC, Parkin M, Roy J, Stahl E, Winchester E, Ziaugra L, Altshuler D, Shen Y, Yao Z, Huang W, Chu X, He Y, Jin L, Liu Y, Shen Y, Sun W, Wang H, Wang Y, Wang Y, Xiong X, Xu L, Waye MM, Tsui SK, Xue H, Wong JT, Galver LM, Fan JB, Gunderson K, Murray SS, Oliphant AR, Chee MS, Montpetit A, Chagnon F, Ferretti V, Leboeuf M, Olivier JF, Phillips MS, Roumy S, Sallee C, Verner A, Hudson TJ, Kwok PY, Cai D, Koboldt DC, Miller RD, Pawlikowska L, Taillon-Miller P, Xiao M, Tsui LC, Mak W, Song YQ, Tam PK, Nakamura Y, Kawaguchi T, Kitamoto T, Morizono T, Nagashima A, Ohnishi Y, Sekine A, Tanaka T, Tsunoda T, Deloukas P, Bird CP, Delgado M, Dermitzakis ET, Gwilliam R, Hunt S, Morrison J, Powell D, Stranger BE, Whittaker P, Bentley DR, Daly MJ, de Bakker PI, Barrett J, Chretien YR, Maller J, McCarroll S, Patterson N, Pe'er I, Price A, Purcell S, Richter DJ, Sabeti P, Saxena R, Schaffner SF, Sham PC, Varilly P, Altshuler D, Stein LD, Krishnan L, Smith AV, Tello-Ruiz MK, Thorisson GA, Chakravarti A, Chen PE, Cutler DJ, Kashuk CS, Lin S, Abecasis GR, Guan W, Li Y, Munro HM, Qin ZS, Thomas DJ, McVean G, Auton A, Bottolo L, Cardin N, Eyheramendy S, Freeman C, Marchini J, Myers S, Spencer C, Stephens M, Donnelly P, Cardon LR, Clarke G, Evans DM, Morris AP, Weir BS, Tsunoda T, Mullikin JC, Sherry ST, Feolo M, Skol A, Zhang H, Zeng C, Zhao H, Matsuda I, Fukushima Y, Macer DR, Suda E, Rotimi CN, Adebamowo CA, Ajayi I, Aniagwu T, Marshall PA, Nkwodimmah C, Royal CD, Leppert MF, Dixon M, Peiffer A, Qiu R, Kent A, Kato K, Niikawa N, Adewole IF, Knoppers BM, Foster MW, Clayton EW, Watkin J, Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Muzny D, Nazareth L, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Wheeler DA, Yakub I, Gabriel SB, Onofrio RC, Richter DJ, Ziaugra L, Birren BW, Daly MJ, Altshuler D, Wilson RK, Fulton LL, Rogers J, Burton J, Carter NP, Clee CM, Griffiths M, Jones MC, McLay K, Plumb RW, Ross MT, Sims SK, Willey DL, Chen Z, Han H, Kang L, Godbout M, Wallenburg JC, L'Archeveque P, Bellemare G, Saeki K, Wang H, An D, Fu H, Li Q, Wang Z, Wang R, Holden AL, Brooks LD, McEwen JE, Guyer MS, Wang VO, Peterson JL, Shi M, Spiegel J, Sung LM, Zacharia LF, Collins FS, Kennedy K, Jamieson R, Stewart J. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449(7164):851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdzinski S, Kornak J, Weiner MW, Meyerhoff DJ. Body mass index and magnetic resonance markers of brain integrity in adults. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(5):652–657. doi: 10.1002/ana.21377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdzinski S, Millin R, Kaiser LG, Durazzo TC, Mueller SG, Weiner MW, Meyerhoff DJ. BMI and Neuronal Integrity in Healthy, Cognitively Normal Elderly: A Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter JL, Bernstein MA, Borowski B, Felmlee JP, Blezek D, Mallozzi R. Validation testing of the MRI calibration phantom for the Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative study; ISMRM 14th Scientific Meeting and Exhibition; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Lantigua R, Stern Y, Chen J, Killeffer EH, Mayeux R. Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(6):481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, Lissner L, Bengtsson C, Bjorkelund C, Skoog I. A 24-year follow-up of body mass index and cerebral atrophy. Neurology. 2004;63(10):1876–1881. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000141850.47773.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, Rothenberg E, Blennow K, Steen B, Skoog I. An 18-year follow-up of overweight and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(13):1524–1528. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzner EP, Luchsinger JA, Scarmeas N, Cosentino S, Brickman AM, Glymour MM, Stern Y. Contribution of vascular risk factors to the progression in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(3):343–348. doi: 10.1001/archneur.66.3.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AJ, Hua X, Lee S, Leow AD, Yanovsky I, Gutman B, Dinov ID, Lepore N, Stein JL, Toga AW, Jack CR, Jr, Bernstein MA, Reiman EM, Harvey DJ, Kornak J, Schuff N, Alexander GE, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Comparing 3 T and 1.5 T MRI for tracking Alzheimer's disease progression with tensor-based morphometry. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009a doi: 10.1002/hbm.20882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AJ, Stein JL, Hua X, Lee S, Hibar DP, Leow A, Dinov ID, Toga AW, Saykin AJ, Shen L, Foroud T, Pankratz N, Huentelman MJ, Craig DW, Gerber JD, Allen A, Corneveaux J, Stephan DA, Webster J, DeChairo BM, Potkin SG, Jack CR, Weiner MW, Raji CA, Lopez OL, Becker JT, Thompson PM. Commonly carried allele within FTO, an obesity-associated gene, relates to accelerated brain degeneration in the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009b doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910878107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Lee S, Yanovsky I, Leow AD, Chou YY, Ho AJ, Gutman B, Toga AW, Jack CR, Jr, Bernstein MA, Reiman EM, Harvey DJ, Kornak J, Schuff N, Alexander GE, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Optimizing power to track brain degeneration in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment with tensor-based morphometry: an ADNI study of 515 subjects. Neuroimage. 2009;48(4):668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Leow AD, Lee S, Klunder AD, Toga AW, Lepore N, Chou YY, Brun C, Chiang MC, Barysheva M, Jack CR, Jr, Bernstein MA, Britson PJ, Ward CP, Whitwell JL, Borowski B, Fleisher AS, Fox NC, Boyes RG, Barnes J, Harvey D, Kornak J, Schuff N, Boreta L, Alexander GE, Weiner MW, Thompson PM, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. 3D characterization of brain atrophy in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment using tensor-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2008a;41(1):19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Leow AD, Parikshak N, Lee S, Chiang MC, Toga AW, Jack CR, Jr, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Tensor-based morphometry as a neuroimaging biomarker for Alzheimer's disease: an MRI study of 676 AD, MCI, and normal subjects. Neuroimage. 2008b;43(3):458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(5):347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrn1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Bernstein MA, Fox NC, Thompson P, Alexander G, Harvey D, Borowski B, Britson PJJLW, Ward C, Dale AM, Felmlee JP, Gunter JL, Hill DL, Killiany R, Schuff N, Fox-Bosetti S, Lin C, Studholme C, DeCarli CS, Krueger G, Ward HA, Metzger GJ, Scott KT, Mallozzi R, Blezek D, Levy J, Debbins JP, Fleisher AS, Albert M, Green R, Bartzokis G, Glover G, Mugler J, Weiner MW. The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(4):685–691. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(3):379–384. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DK, Wilkins CH, Morris JC. Accelerated weight loss may precede diagnosis in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(9):1312–1317. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.9.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovicich J, Czanner S, Greve D, Haley E, van der Kouwe A, Gollub R, Kennedy D, Schmitt F, Brown G, Macfall J, Fischl B, Dale A. Reliability in multi-site structural MRI studies: effects of gradient non-linearity correction on phantom and human data. Neuroimage. 2006;30(2):436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J Chronic Dis. 1972;25(6):329–343. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(72)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Kareholt I, Winblad B, Helkala EL, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Nissinen A. Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(10):1556–1560. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov P, Lancaster JL, Thompson P, Woods R, Mazziotta J, Hardies J, Fox P. Regional spatial normalization: toward an optimal target. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25(5):805–816. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200109000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuller LH, Shemanski L, Manolio T, Haan M, Fried L, Bryan N, Burke GL, Tracy R, Bhadelia R. Relationship between ApoE, MRI findings, and cognitive function in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 1998;29(2):388–398. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa K, Kabeto M, Weirm D. Health and Retirement Study, unpublished data from the 2006 survey provided under contract to the Alzheimer's Association. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Leow A, Huang SC, Geng A, Becker J, Davis S, Toga A, Thompson P. Inverse consistent mapping in 3D deformable image registration: its construction and statistical properties. Inf Process Med Imaging. 2005;19:493–503. doi: 10.1007/11505730_41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leow AD, Yanovsky I, Parikshak N, Hua X, Lee S, Toga AW, Jack CR, Jr, Bernstein MA, Britson PJ, Gunter JL, Ward CP, Borowski B, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Fleisher AS, Harvey D, Kornak J, Schuff N, Alexander GE, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative: a one-year follow up study using tensor-based morphometry correlating degenerative rates, biomarkers and cognition. Neuroimage. 2009;45(3):645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore N, Joshi AA, Leahy RM, Brun C, Chou YY, Pennec X, Lee AD, Barysheva M, Zubricaray GI, Wright MJ, McMahon KL, Toga AW, Thompson PM. A New Combined Surface and Volume Registration. SPIE Medical Imaging. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Becker JT, Jagust WJ, Fitzpatrick A, Carlson MC, DeKosky ST, Breitner J, Lyketsos CG, Jones B, Kawas C, Kuller LH. Neuropsychological characteristics of mild cognitive impairment subgroups. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):159–165. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.045567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, Becker JT, Fitzpatrick A, Dulberg C, Breitner J, Lyketsos C, Jones B, Kawas C, Carlson M, Kuller LH. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study: part 1. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(10):1385–1389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubinski D. Cognitive epidemiology: With emphasis on untagling cognitive ability and socioeconomic status. Intelligence. 2009;(37):625–633. [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Honig LS, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R. Aggregation of vascular risk factors and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65(4):545–551. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172914.08967.dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luders E, Gaser C, Narr KL, Toga AW. Why sex matters: brain size independent differences in gray matter distributions between men and women. J Neurosci. 2009a;29(45):14265–14270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2261-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luders E, Narr KL, Thompson PM, Toga AW. Neuroanatomical Correlates of Intelligence. Intelligence. 2009b;37(2):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta J, Toga A, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J, Zilles K, Woods R, Paus T, Simpson G, Pike B, Holmes C, Collins L, Thompson P, MacDonald D, Iacoboni M, Schormann T, Amunts K, Palomero-Gallagher N, Geyer S, Parsons L, Narr K, Kabani N, Le Goualher G, Boomsma D, Cannon T, Kawashima R, Mazoyer B. A probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain: International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1412):1293–1322. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel M. Big-brained people are smarter: A meta-analysis of the relationship between in vivo brain volume and intelligence. Intelligence. 2005;33:337–346. [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz N, Tong M, Longato L, Xu H, de la Monte SM. Limited Alzheimer-type neurodegeneration in experimental obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15(1):29–44. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrak RE. Alzheimer-type neuropathological changes in morbidly obese elderly individuals. Clin Neuropathol. 2009;28(1):40–45. doi: 10.5414/npp28040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SG, Weiner MW, Thal LJ, Petersen RC, Jack C, Jagust W, Trojanowski JQ, Toga AW, Beckett L. The Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2005a;15(4):869–877. xi–xii. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SG, Weiner MW, Thal LJ, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Jagust W, Trojanowski JQ, Toga AW, Beckett L. Ways toward an early diagnosis in Alzheimer's disease: The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Alzheimers Dement. 2005b;1(1):55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, Burke JR, Hurd MD, Potter GG, Rodgers WL, Steffens DC, Willis RJ, Wallace RB. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1–2):125–132. doi: 10.1159/000109998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113(6):898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raji CA, Ho AJ, Parikshak NN, Becker JT, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Hua X, Leow AD, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Brain structure and obesity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009a doi: 10.1002/hbm.20870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raji CA, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, O.T C, Becker JT. Age, Alzheimer's Disease, and Brain Structure. Neurology. 2009b doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c3f293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The role of memory in the age decline in digit-symbol substitution performance. J Gerontol. 1978;33(2):232–238. doi: 10.1093/geronj/33.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuff N, Woerner N, Boreta L, Kornfield T, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Thompson PM, Jack CR, Jr, Weiner MW. MRI of hippocampal volume loss in early Alzheimer's disease in relation to ApoE genotype and biomarkers. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 4):1067–1077. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17(1):87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J, Cai J, Juhaeri, Thun MJ, Williamson DF, Wood JL. Consequences of the use of different measures of effect to determine the impact of age on the association between obesity and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(4):399–407. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studholme C, Cardenas V, Maudsley A, Weiner M. An intensity consistent filtering approach to the analysis of deformation tensor derived maps of brain shape. Neuroimage. 2003;19(4):1638–1649. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taki Y, Kinomura S, Sato K, Inoue K, Goto R, Okada K, Uchida S, Kawashima R, Fukuda H. Relationship between body mass index and gray matter volume in 1,428 healthy individuals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(1):119–124. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, Manolio TA, Newman AB, Borhani NO. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3(4):358–366. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, de Zubicaray G, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, Herman D, Hong MS, Dittmer SS, Doddrell DM, Toga AW. Dynamics of gray matter loss in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23(3):994–1005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00994.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, Sowell ER, Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, de Zubicaray GI, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, Doddrell DM, Wang Y, van Erp TG, Cannon TD, Toga AW. Mapping cortical change in Alzheimer's disease, brain development, and schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2004;23 Suppl 1:S2–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Martin NG. The ENIGMA Network. 2010 http://enigmaloniuclaedu. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Mega MS, Woods RP, Zoumalan CI, Lindshield CJ, Blanton RE, Moussai J, Holmes CJ, Cummings JL, Toga AW. Cortical change in Alzheimer's disease detected with a disease-specific population-based brain atlas. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11(1):1–16. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson GS, Peskind ER, Asthana S, Purganan K, Wait C, Chapman D, Schwartz MW, Plymate S, Craft S. Insulin increases CSF Abeta42 levels in normal older adults. Neurology. 2003;60(12):1899–1903. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000065916.25128.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer RA, Gunderson EP, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Zhou J, Yaffe K. Body mass index in midlife and risk of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(2):103–109. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Kanaya A, Lindquist K, Simonsick EM, Harris T, Shorr RI, Tylavsky FA, Newman AB. The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline. Jama. 2004;292(18):2237–2242. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Heshka S, Wang Z, Shen W, Allison DB, Ross R, Heymsfield SB. Combination of BMI and Waist Circumference for Identifying Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Whites. Obes Res. 2004;12(4):633–645. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]