Abstract

A prominent phenotype of IRF8 knock out (IRF8 KO) mice is the uncontrolled expansion of immature myeloid cells. The molecular mechanism underlying this myeloproliferative syndrome is still elusive. In this study, we observed that Bax expression level is low in bone marrow (BM) preginitor cells and increased dramatically in primary myeloid cells in wt mice. In contrast, Bax expression level remained at low level in primary myeloid cells in IRF8 KO mice. However, in vitro IRF8 KO BM-differentiated myeloid cells expressed Bax at a level as high as that in wt myeloid cells. Furthermore, we demonstrated that IRF8 specifically binds to the Bax promoter region in primary myeloid cells. Functional analysis indicated that IRF8 deficiency results in increased resistance of the primary myeloid cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Our findings thus determine that IRF8 directly regulates Bax transcription in vivo but no in vitro during myeloid cell lineage differentiation.

Keywords: Bax, Fas, Myeloid cell, IRF8

Introduction

All types of immune cells are derived from the hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow (BM) through a hierarchical differentiation process. This differentiation process is tightly regulated by lineage-specific transcription factors (1). IFN regulatory factor 8 (IRF8/ICSBP) is such a key transcription factor that regulates myeloid cell and B cell differentiation under physiological conditions (2-4). IRF8 knock out (KO) mice and mice with a mutation in the IRF8/ICSBP gene develop a myeloproliferative syndrome with uncontrolled clonal expansion of undifferentiated myeloid cells (2, 5). The molecular mechanisms underlying myeloproliferative syndrome in IRF8-deficient mice is still elusive. Previous studies have identified multiple apoptosis-related genes, including FAP-1, FLIP, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, that are regulated by IRF8 in myeloid cell lines in vitro (6-12). These prominent studies suggest that the myeloproliferative syndrome of IRF8-deficient mice may be due to altered sensitivity of myeloid cells to apoptosis in vitro. However, these studies also suggest that regulation of apoptosis-related genes by IRF8 is cell type-dependent. Furthermore, it has been shown that regulation of Bcl-2 by IRF8 observed in vitro might not be observed in vivo (10).

In this study, we compared the genome-wide gene expression profiles of CD11b+ primary myeloid cells purified from wt and IRF8 KO mice and identified that Bax is an IRF8 target gene in vivo but not in vitro. Our data suggest that IRF8 directly binds to the Bax promoter region to activate Bax transcription and loss of IRF8 expression significantly decreases primary myeloid cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Thus, our results suggest that IRF8 might mediate myeloid cell differentiation partially through regulating Bax expression and the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Mice

IRF8 knock out mice (kindly provided by Dr. Keiko Ozato) were maintained as described (5). All IRF8 KO mice used for the study were between the ages of 43 to 60 days. To generate chimeric mice, wt C57BL/6 recipient mice were irradiated with a dose of 950 Rad. BM cells from IRF8 KO and age-matched littermate wt mice (5×106 cells/mouse) were injected 4h later to the irradiated mice. Mice were used 30 days after BM transplantation. All mice were studied in accordance with approved Georgia Health Sciences University protocols.

DNA Microarray

CD11b+ cells were isolated from spleen cells using anti-CD11b mAb (Biolegend) and magnetic beads. DNA microarray analysis of genome wide gene expression with mouse OneArray (Phalanx Biotech) was carried out as previously described (13).

RT-PCR analysis

RT-PCR analysis was carried out as previously described (14). The PCR primer sequences are as follows: mouse Bax: forward: 5’- GGATGCGTCCACCAAGAAGC -3’, reverse: 5’-GGAGGAAGTCCAGTGTCCAGCC-3’. Quantitative PCR reactions were done in a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystem).

Western blotting analysis

CD11b+, CD4+, CD8+ and NK+ cells were isolated from minced spleens with the respective mAb (Biolegend) and magnetic beads. Western blotting analysis was carried out as previously described (15). The blots were probed with the following antibodies: anti-IRF8 (C-19, Santa Cruz) at a 1:200 dilution; anti-Cytochrome C (BD Biosciences) at 1:500; anti-Bax (Santa Cruz) at 1:2000, anti-cleaved PARP (Cell Signal) at 1:500, and anti-β-actin (Sigma, At Louis, MO) at 1:8000. Blots were detected using the ECL Plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) Western detection kit.

Cell surface marker analysis

Spleens were minced to make single cell suspension through a cell strainer (BD Biosciences). The cell suspension was stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b mAb (BD Biosciences). The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (16).

Cytosol and mitochondra fractionation

Cytosol and mitochondrion-enriched fractions were prepared as previously described (17).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

CD11b+ cells were purified by depleting other subsets of cells with respective mAbs and magnetic beads. ChIP assays were carried out according to protocols from Upstate Biotech (Lake Placid, NY) as previously described (13). Immunoprecipitation was carried out using anti-IRF8 antibody (C-19, Santa Cruz) and agarose-protein A beads (Upstate). The PCR primers used to amplify the promoter region of the Bax gene as depicted in Figure 3A are as follows: ChIP 1: forward: 5’-GGGAAGGGCAGGTTTTAGAG-3’, reverse: 5’-TGCCTAGGGAATGGAGTCAC-3’; ChIP2: forward: 5’-TGGGTGCTTTCAGAGCTTTT-3’, reverse: 5’-TTTAATCCCAGCCCTCAGAA-3’, ChIP3: forward: 5’-GAAAGGAGGGGAGGAGAAGTAGTG-3’, reverse: 5’-GAAAGGAGGGGAGGAGAAGTAGTG-3’; ChIP4: forward: 5’-CTGGGGGTCTGTTTGCTTTTG-3’, reverse: 5’-GGGATGGATAGGTAGGCTCATAACC-3’.

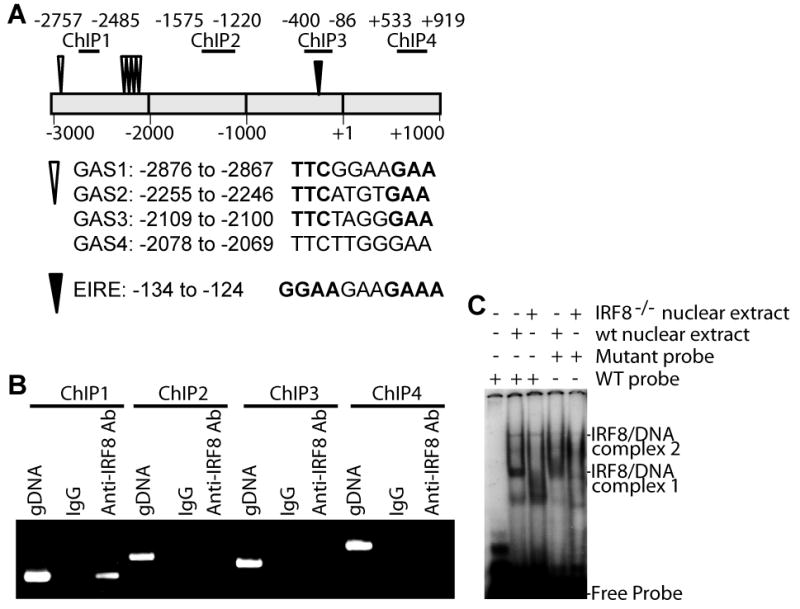

Figure 3. IRF8 binds to the Bax promoter in primary myeloid cells.

A. The mouse Bax promoter structure. The ChIP PCR regions are indicated at the top. The numbers indicate nucleotide locations relative to the Bax transcription initiation site. Locations of IRF8 binding consensus sequence elements (GAS and EIRE) are also indicated. B. ChIP analysis of IRF8 binding to the Bax promoter in purified primary myeloid cells. gDNA: Genomic DNA positive control. C. IRF8 binding to the Bax promoter DNA elements in vitro. A GAS1-containing DNA was used as probe in the EMSA. The potential probe-IRF8 complexes are indicated at the right.

Protein-DNA interaction assay

Electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) was carried out as previously described (18). The DNA probes are as follows: GAS wt probe: forward: 5’- ACCTTCGGAAGAACAG-3’, reverse: 5’-CTGTTCTTCCGAAGGT-3’; GAS mutant probe: forward: 5’- ACCTAGGGAACTACAG-3’, reverse: 5’- CTGTAGTTCCCTAGGT-3; Oligonucleotides were annealed and end-labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP and used for EMSA as previously described (18).

Measurement of apoptotic cell death

Total spleen cells were cultured in the absence or presence of FasL (10 ng/ml) overnight. The cells were then collected and stained with anti-CD11b mAb (BD Biosciences) and Alex Fluor 647-conjugated Annexin V. The CD11b+ cells were gated out to determine the percentage of Annexin V+ CD11b+ cells. The percentage of cell death was calculated by the formula: % cell death=% Annexin V+ cells with FasL treatment - % Annexin V+ cells without FasL treatment.

Results

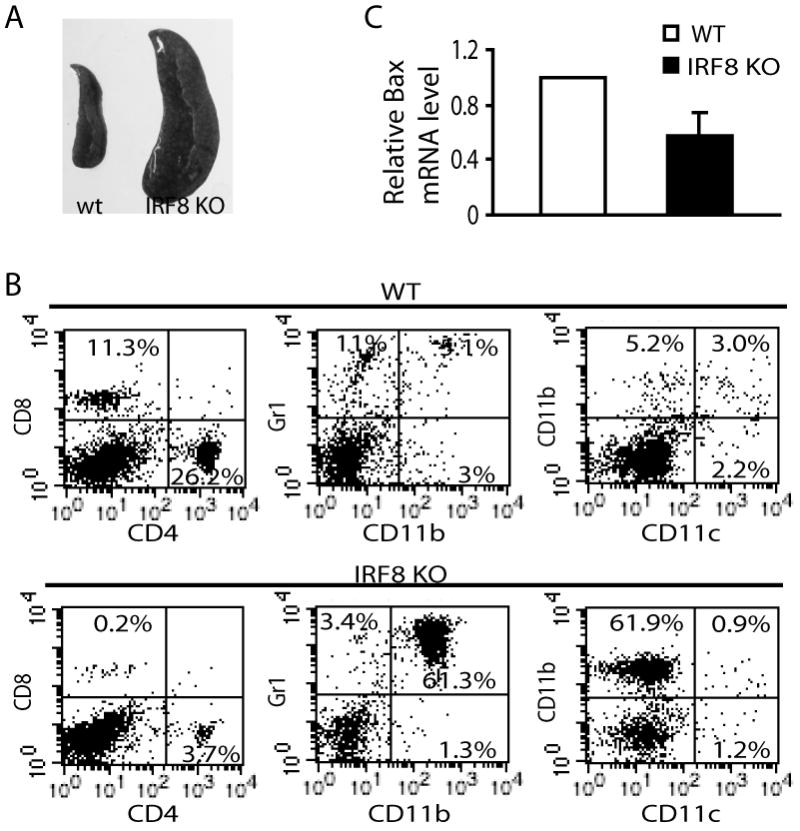

Identification of Bax as a target of IRF8

As noted before, the size of the spleen from IRF8 KO mice was significantly larger than that from wt mice (Fig. 1A). The number of Gr1+ and CD11b+ cells that likely include macrophages and granulocytes are dramatically increased in the spleen of the IRF8 KO mice and accounts for morethan 50% of the total spleen cells (Fig. 1B), thus validating the function of IRF8 as a key transcription factor in lineage-specific differentiation of myeloid cells (5, 19).

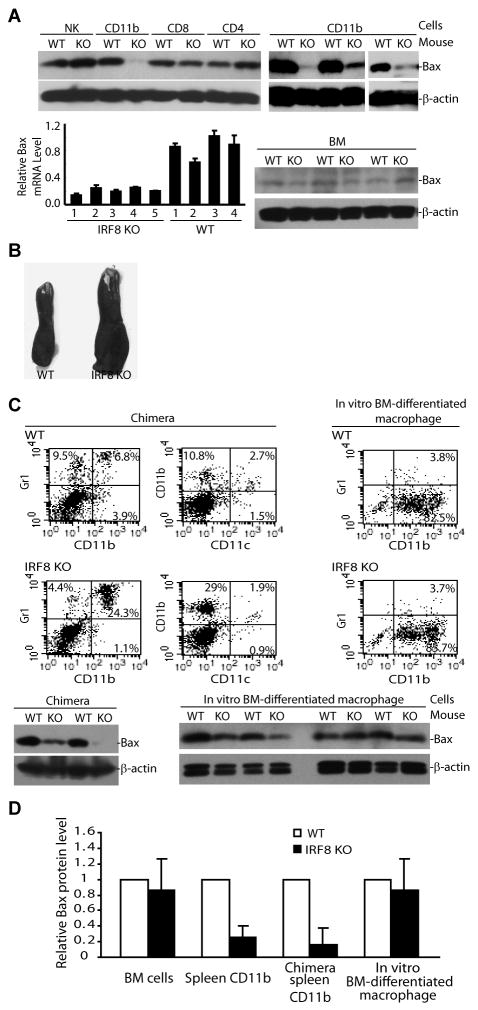

Figure 1. Identification of Bax as an IRF8 target gene in primary myeloid cells.

A. Spleens of wt (left) and IRF8 KO (right) mice. B. Single cell suspension was prepared from spleens of IRF8 KO and age-matched wt littermate control mice, and analyzed for subsets of immune cells as indicated. The number in the box indicates the percentage of that subset of cells. Shown are representative data from one of 3 pairs of mice. C. Differential Bax gene expression between wt and IRF8 KO primary CD11b+ myeloid cells. Data were derived from DNA microarray analysis. The expression of Bax in wt CD11b+ myeloid cells was set as 1.

DNA microarray analysis of purified CD11b+ cells from IRF8 KO mice and age-matched littermate control wt mice revealed that among the 26,423 transcript probes analyzed, the expression levels of 1047 genes changed at least 1.6 folds (GEO Accession # GSE31464, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE31464). Gene ontology (GO) biological process-based classification (http://www.pantherdb.org/genes/batchIdSearch.jsp) identified 42 genes (Supplemental Table 1), including Bax (Fig. 1C), with known function in apoptosis.

Western blotting analysis revealed that Bax protein level is also dramatically lower in IRF8 KO CD11b+ primary cells than in wt CD11b+ primary cells (Fig. 2A & B). However, Bax protein level is not significantly different in CD4+ CD8+ and NK cells between the IRF8 KO and wt control mice (Fig. 2A). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis indicates that the Bax mRNA level is significantly lower in IRF8 KO CD11b+ primary cells than in the CD11b+ primary cells of age-matched wt littermate control mice (Fig. 2A). The Bax protein level is low in BM cells of both wt and IRF8 KO mice (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. IRF8 regulates Bax expression in myeloid cells in vivo.

A. Western blotting analysis of Bax protein levels in subsets of immune cells (top panel) and bone marrow (BM, bottom right panel) cells. The indicated subsets of immune cells were isolated from the spleens of IRF8 KO and age-matched littermate wt control mice and analyzed by Western blotting analysis. Total RNA was also isolated from CD11b+ cells of the spleens of wt (n=4) and IRF8 KO (n=5) mice and analyzed for Bax mRNA level by real-time PCR (bottom right panel). B. Image showing the sizes of spleens from chimera mice with wt and IRF8 KO BM. C. Subsets of immune cells of spleens from chimera mice (top left panel) and in vitro-differentiated macrophage (top right panel) were analyzed as in Fig. 1B. CD11b+ cells purified from spleens of wt and IRF8 KO chimera mice (bottom left panel) and in vitro BM-differentiated macrophage cells (bottom right panel) were then analyzed for Bax protein level by Western blotting analysis. D. Quantification of Bax protein level as shown above. The levels of Bax protein in the respective wt cells were set as 1. Column: mean; bar: SD.

Lethally irradiated wt mice that received BM from IRF8 KO mice also exhibited splenomegaly (Fig. 2B). These IRF8 KO chimera mice showed similar immune cell profiles (Fig. 2C) to the conventional IRF8 KO mice (Fig. 1B). The Bax protein level of these IRF8 KO chimera mice is also dramatically lower than that in wt chimera mice (Fig. 2C). In vitro differentiation of BM cells from both wt and IRF8 KO mice with GM-CSF and M-CSF generated CD11b+ cells (Fig. 2C). However, Bax protein level of these in vitro-differentiated IRF8 KO CD11b+ cells is as high as that in wt CD11b+ cells (Fig. 2C & D). Taken together, our data suggest that IRF8 regulates Bax expression in vivo but not in vitro during myeloid cell differentiation (Fig. 2D).

IRF8 protein binds to the Bax promoter

ChIP assays were then carried out with purified wt CD11b+ primary cells to determine whether IRF8 protein is associated with the Bax promoter. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, the Bax promoter region contains several IRF8 consensus binding elements (GAS and EIRE) (Fig. 3A) (20-21). Specific IRF8 binding was detected in one region of the Bax promoter (Fig. 3B). EMSA with nuclear extracts from purified wt and IRF8 KO CD11b+ cells indicated that IRF8 directly interacts with one of the GAS elements in the Bax promoter region (GAS1, Fig. 3C). Initial attempt did not detect IRF8 binding to a DNA probe containing GAS2-4 (Data not shown). Our data thus suggest that IRF8 may directly binds to the Bax promoter in primary CD11b+ cells.

IRF8-deficient myeloid cells exhibit decreased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis

The above observation that IRF8 KO myeloid cells exhibit decreased Bax expression leads us to speculate that the IRF8 KO cells might acquire resistance to apoptosis. To test this hypothesis, we first measured cytochrome C (CytC) release, a biochemical marker for the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, in purified primary CD11b+ cells. Spontaneous CytC release is higher in purified wt CD11b+ cells ex vivo as compared to IRF8 KO cells (Fig. 4A). Treatment with FasL induced a rapid increase in CytC release in wt CD11b+ cells but not in IRF8 KO CD11b+ cells (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the CytoC release pattern, cleaved PARP, a biochemical marker of both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis, was also observed in wt but not in IRF8 KO CD11b+ primary cells (Fig. 4A). At the functional level, the wt CD11b+ primary cells exhibited significantly more spontaneous apoptosis ex vivo with FasL further increasing the apoptosis rate. However, the IRF8 KO CD11b+ cells exhibited significantly less spontaneous apoptosis and became less sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis ex vivo (Fig. 4B). Taken together, our data suggest that loss of IRF8 function decreases CD11b+ primary cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

Figure 4. IRF8 KO primary myeloid cells exhibit increased resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

A. CD11b+ primary myeloid cells were isolated from spleens of IRF8 KO and age-matched littermate control wt mice. The cells were treated with FasL in vitro (10ng/ml) for the indicated time. Cytochrome C and cleaved PARP levels in the cytosol were analyzed by Western blotting analysis. Shown is one representative result of two independent experiments. B. IRF8 KO myeloid cells exhibit increased resistance to apoptosis than the wt myeloid cells. Single cell suspension was prepared from spleens of IRF8 KO and age-matched littermate control mice. Cells were incubated with FasL (10 ng/ml) in vitro for approximately 6 h. The cells were then stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD11b mAb and Alex Flour 647-conjugated Annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD11b+ cells were gated to determine the annexin V+ cells. Shown are representative results of one of 3 independent experiments. Bottom right panel: quantification of FasL-induced apoptosis. The % FasL-induced cell death was calculated by the formula: % annexin V+ cells in the presence of FasL - % annexin V+ cells in the absence of FasL. Column, mean; Bar, SD.

Discussion

IRF8 is essential for myeloid cell differentiation and loss of IRF8 expression leads to uncontrolled clonal expansion of CD11b+ myeloid cells (5). It has been proposed that acquisition of apoptosis resistance is responsible for the impaired myeloid cell differentiation (6-12). Several apoptosis regulators, including Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, FAP-1 and acid ceramidase have been shown to play a role in regulating apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cell lines in vitro (6-8, 16). IRF8 has also been shown to regulate FLIPL expression in primary myeloid cells in vivo (17). The function of IRF8 in apoptosis has also been demonstrated in other non-hematopoietic cells (17, 22-24). In addition, it has been shown that the correlation between IRF8 and the Bcl-2 family members observed in vitro may not be observed in vivo (10). Therefore, IRF8’s function in regulation of apoptosis-related genes might be cell type-dependent and different between in vitro and in vivo conditions. Our data indicates that IRF8 directly binds to the Bax promoter to regulate Bax transcription in primary myeloid cells in vivo but not in vitro.

The Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway plays an essential role in the elimination of unwanted cells by the host immune system during lineage differentiation and homeostasis (25-26). Bax is a key mediator of the mitochondrion-dependent intrinsic apoptosis pathway (27). Our data indicate that IRF8 is a transcription activator of Bax. Therefore, IRF8 might mediate myeloid homeostasis and differentiation through regulating Bax expression to maintain the myeloid cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. However, IRF8 also regulates the expression of other apoptosis-related genes in primary myeloid cells in vivo (Supplemental Figure 1). Therefore, the relative role of Bax and other IRF8-regulated and apoptosis-related genes in IRF8-mediated myeloid cell differentiation in vivo requires further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeanene Pihkala for assistance in flow cytometry analysis.

Grant support: National Institutes of Health (CA133085 to K.L), the American Cancer Society (RSG-09-209-01-TBG to K.L).

References

- 1.Tsujimura H, Nagamura-Inoue T, Tamura T, Ozato K. IFN consensus sequence binding protein/IFN regulatory factor-8 guides bone marrow progenitor cells toward the macrophage lineage. J Immunol. 2002;169:1261–1269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tailor P, Tamura T, Morse HC, 3rd, Ozato K. The BXH2 mutation in IRF8 differentially impairs dendritic cell subset development in the mouse. Blood. 2008;111:1942–1945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saberwal G, Horvath E, Hu L, Zhu C, Hjort E, Eklund EA. The interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP/IRF8) activates transcription of the FANCF gene during myeloid differentiation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:33242–33254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng J, Wang H, Shin DM, Masiuk M, Qi CF, Morse HC., 3rd IFN regulatory factor 8 restricts the size of the marginal zone and follicular B cell pools. J Immunol. 2011;186:1458–1466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holtschke T, Lohler J, Kanno Y, Fehr T, Giese N, Rosenbauer F, Lou J, Knobeloch KP, Gabriele L, Waring JF, Bachmann MF, Zinkernagel RM, Morse HC, 3rd, Ozato K, Horak I. Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell. 1996;87:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriele L, Phung J, Fukumoto J, Segal D, Wang IM, Giannakakou P, Giese NA, Ozato K, Morse HC. Regulation of apoptosis in myeloid cells by interferon consensus sequence-binding protein. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1999;190:411–421. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang W, Zhu C, Wang H, Horvath E, Eklund EA. The interferon consensus sequence-binding protein (ICSBP/IRF8) represses PTPN13 gene transcription in differentiating myeloid cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:7921–7935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burchert A, Cai D, Hofbauer LC, Samuelsson MK, Slater EP, Duyster J, Ritter M, Hochhaus A, Muller R, Eilers M, Schmidt M, Neubauer A. Interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP; IRF-8) antagonizes BCR/ABL and down-regulates bcl-2. Blood. 2004;103:3480–3489. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middleton MK, Zukas AM, Rubinstein T, Jacob M, Zhu P, Zhao L, Blair I, Pure E. Identification of 12/15-lipoxygenase as a suppressor of myeloproliferative disease. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:2529–2540. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenigsmann J, Carstanjen D. Loss of Irf8 does not co-operate with overexpression of BCL-2 in the induction of leukemias in vivo. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:2078–2082. doi: 10.3109/10428190903296913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koenigsmann J, Rudolph C, Sander S, Kershaw O, Gruber AD, Bullinger L, Schlegelberger B, Carstanjen D. Nf1 haploinsufficiency and Icsbp deficiency synergize in the development of leukemias. Blood. 2009;113:4690–4701. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konieczna I, Horvath E, Wang H, Lindsey S, Saberwal G, Bei L, Huang W, Platanias L, Eklund EA. Constitutive activation of SHP2 in mice cooperates with ICSBP deficiency to accelerate progression to acute myeloid leukemia. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:853–867. doi: 10.1172/JCI33742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman M, Yang D, Hu X, Liu F, Singh N, Browning D, Ganapathy V, Chandler V, Choubey D, Abrams SI, Liu K. IFN-γ Upregulates Survivin and Ifi202 Expression to Induce Survival and Proliferation of Tumor-Specific T Cells. PloS one. 2010;5:e14076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang D, Ud Din N, Browning DD, Abrams SI, Liu K. Targeting lymphotoxin beta receptor with tumor-specific T lymphocytes for tumor regression. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5202–5210. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F, Hu X, Zimmerman M, Waller J, Wu P, Hayes-Jordan A, Lev D, Liu K. TNFα Cooperates with IFN-γ to Repress Bcl-xL Expression to Sensitize Metastatic Colon Carcinoma Cells to TRAIL-mediated Apoptosis. PloS one. 2011;6:e16241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu X, Yang D, Zimmerman M, Liu F, Yang J, Kannan S, Burchert A, Szulc Z, Bielawska A, Ozato K, Bhalla K, Liu K. IRF8 regulates acid ceramidase expression to mediate apoptosis and suppresses myelogeneous leukemia. Cancer research. 2011;71:2882–2891. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang D, Wang S, Brooks C, Dong Z, Schoenlein PV, Kumar V, Ouyang X, Xiong H, Lahat G, Hayes-Jordan A, Lazar A, Pollock R, Lev D, Liu K. IFN regulatory factor 8 sensitizes soft tissue sarcoma cells to death receptor-initiated apoptosis via repression of FLICE-like protein expression. Cancer research. 2009;69:1080–1088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGough JM, Yang D, Huang S, Georgi D, Hewitt SM, Rocken C, Tanzer M, Ebert MP, Liu K. DNA methylation represses IFN-gamma-induced and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-mediated IFN regulatory factor 8 activation in colon carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1841–1851. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura T, Nagamura-Inoue T, Shmeltzer Z, Kuwata T, Ozato K. ICSBP directs bipotential myeloid progenitor cells to differentiate into mature macrophages. Immunity. 2000;13:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanno Y, Levi BZ, Tamura T, Ozato K. Immune cell-specific amplification of interferon signaling by the IRF-4/8-PU.1 complex. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:770–779. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li P, Wong JJ, Sum C, Sin WX, Ng KQ, Koh MB, Chin KC. IRF8 and IRF3 cooperatively regulate rapid interferon-{beta} induction in human blood monocytes. Blood. 2011;117:2847–2854. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egwuagu CE, Li W, Yu CR, Che Mei Lin M, Chan CC, Nakamura T, Chepelinsky AB. Interferon-gamma induces regression of epithelial cell carcinoma: critical roles of IRF-1 and ICSBP transcription factors. Oncogene. 2006;25:3670–3679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang D, Thangaraju M, Greeneltch K, Browning DD, Schoenlein PV, Tamura T, Ozato K, Ganapathy V, Abrams SI, Liu K. Repression of IFN regulatory factor 8 by DNA methylation is a molecular determinant of apoptotic resistance and metastatic phenotype in metastatic tumor cells. Cancer research. 2007;67:3301–3309. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang D, Thangaraju M, Browning DD, Dong Z, Korchin B, Lev DC, Ganapathy V, Liu K. IFN Regulatory Factor 8 Mediates Apoptosis in Nonhemopoietic Tumor Cells via Regulation of Fas Expression. J Immunol. 2007;179:4775–4782. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha P, Chornoguz O, Clements VK, Artemenko KA, Zubarev RA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells express the death receptor Fas and apoptose in response to T cell-expressed FasL. Blood. 2011;117:5381–5390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel RM, Chan FK, Chun HJ, Lenardo MJ. The multifaceted role of Fas signaling in immune cell homeostasis and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:469–474. doi: 10.1038/82712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science (New York, N Y) 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.