Abstract

Background

The use of zoledronic acid (ZOL) has recently been shown to significantly reduce the risk of new skeletal-related events (SREs) in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients with bone metastases. The present exploratory study assessed the cost-effectiveness of ZOL in this population, adopting a French, German, and United Kingdom (UK) government payer perspective.

Materials and methods

This cost-effectiveness model was based on a post hoc retrospective analysis of a subset of patients with RCC who were included in a larger randomized clinical trial of patients with bone metastases secondary to a variety of cancers. In the trial, patients were randomized to receive ZOL (n = 27) or placebo (n = 19) with concomitant antineoplastic therapy every 3 weeks for 9 months (core study) plus 12 months during a study extension. Since the trial did not collect costs or data on the quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) of the patients, these outcomes had to be assumed via modeling exercises. The costs of SREs were estimated using hospital DRG tariffs. These estimates were supplemented with literature-based costs where possible. Drug, administration, and supply costs were obtained from published and internet sources. Consistent with similar economic analyses, patients were assumed to experience quality of life decrements lasting 1 month for each SRE. Uncertainty surrounding outcomes was addressed via multivariate sensitivity analyses.

Results

Patients receiving ZOL experienced 1.07 fewer SREs than patients on placebo. Patients on ZOL experienced a gain in discounted QALYs of approximately 0.1563 in France and Germany and 0.1575 in the UK. Discounted SRE-related costs were substantially lower among ZOL than placebo patients (−€ 4,196 in France, −€ 3,880 in Germany, and −€ 3,355 in the UK). After taking into consideration the drug therapy costs, ZOL saved € 1,358, € 1,223, and € 719 in France, Germany, and the UK, respectively. In the multivariate sensitivity analyses, therapy with ZOL saved costs in 67–77% of simulations, depending on the country. The cost per QALY gained for ZOL versus placebo was below € 30,000 per QALY gained threshold in approximately 93–94% of multivariate sensitivity analyses simulations.

Conclusions

The present analysis suggests that ZOL saves costs and increases QALYs compared to placebo in French, German, and UK RCC patients with bone metastases. Additional prospective research may be needed to confirm these results in a larger sample of patients.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, Bone health, Cost-effectiveness, Bone metastases, Bisphosphonates

Introduction

Patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) are at a high risk for developing skeletal-related events (SREs) [1, 2]. Approximately 80% of RCC patients with bone metastases eventually require radiotherapy, 40% experience a long-bone fracture, and 30% require orthopedic surgery or develop hypercalcemia [1]. Health status, quality of life, and survival are negatively impacted by these SREs [3, 4]. In addition, the cost of managing SREs due to cancer is substantial [5, 6].

Bisphosphonates are increasingly used to prevent the burden of SREs in patients with bone metastases [7]. Zoledronic acid (ZOL) is the only bisphosphonate proven to safely and effectively reduce SREs in RCC patients with bone metastases. Specifically, ZOL was investigated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III trial in patients with bone metastases secondary to solid tumors other than breast or prostate cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer, RCC, and bladder cancer [8, 9]. The incidence of SREs was particularly high among the subgroup of patients with RCC (which included 27 patients receiving ZOL 4 mg and 19 patients receiving placebo, both administered as a 15-min infusion) [10], demonstrating the aggressive nature of bone metastases from RCC. A post hoc analysis by Lipton et al. [10] revealed that ZOL was efficacious in patients with RCC. During the 9-month trial [10], ZOL (a) significantly reduced the proportion of patients with an SRE by 50% (37% versus 74% with placebo, P ≤ 0.015); (b) consistently reduced the proportion of patients with each type of SRE; (c) significantly prolonged time to first SRE (median not reached at 270 days versus 72 days for placebo, P ≤ 0.006); (d) significantly delayed the time to first pathological fracture (median not reached at 9 months versus 168 days for placebo); (e) significantly reduced the skeletal morbidity rate by 21% (2.68 versus 3.38 events per year for placebo; P ≤ 0.014); and (f) significantly reduced the risk of SRE (risk ratio, 0.394; 95% confidence interval, 0.193–0.806; P ≤ 0.008) in an Andersen-Gill multiple event analysis (which incorporated the incidence and timing of all of the SREs throughout the study and accounts for inter- and intrapatient variations in event rate). In this trial, ZOL was well tolerated by RCC patients. The clinical adverse event (AE) profile in patients receiving ZOL was similar to placebo. Compared to placebo, AEs with greater incidences in the ZOL treatment arm included nausea, anemia, pyrexia, emesis, and dyspnea. The renal safety profile of ZOL was comparable to placebo [10]. In contrast to the available data regarding ZOL, there is no evidence regarding the effects of other bisphosphonates (e.g., pamidronate) in patients with RCC.

Given the substantial burden of SREs and the high efficacy of ZOL in the RCC patient population, we hypothesized that the use of ZOL in this setting would be highly cost-effective. This hypothesis was based on the previous analyses showing that ZOL is cost-effective in solid tumors other than RCC, such as breast [11], prostate [12], and lung [13]. Therefore, the purpose of the present analysis was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of ZOL versus placebo in RCC patients with bone metastases. The analysis was conducted from a government payer perspective in the three most populous European Union (EU) countries, namely, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (UK), which account for approximately two-fifths of the nearly 500 million European Union populations.

Materials and methods

Study design

An economic model was conducted to estimate the cost-effectiveness of ZOL versus placebo in RCC patients with bone metastases. The most universally accepted, and, in some countries, mandated method to assess value is the “cost utility analysis”, a form of cost-effectiveness analysis in which health effects are measured in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained. A QALY is a measure that incorporates both the quantity of life (how long a therapy improves survival) and the quality of life (how desirable the additional survival is). Measuring the desirability of a health state is accomplished via the use of utility, which is a quantitative expression of an individual’s preference for a particular health state.

Therefore, in the present analysis, the main outcome measure was the incremental cost-utility ratio (ICUR) of using ZOL as opposed to placebo (i.e., no bisphosphonate), which calculates the additional costs (over placebo) associated with the use of ZOL to achieve a gain of one additional QALY (over placebo).

The analysis included direct medical costs associated with ZOL drug costs, drug administration and supplies, and the direct costs of SREs. It excluded indirect (i.e., productivity) costs incurred (or avoided) by the patients, as the median age of the patients in the trial was approximately 65 years and it was assumed that the majority of them would be out of the labor force due to their age and/or the advance nature of their cancer.

The analysis was based on patient-level data (obtained from the manufacturer of ZOL, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation, Florham Park, NJ, USA) from a subset of RCC patients [10] enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of ZOL in patients with bone metastases from lung or other solid tumors [8, 9]. In the trial, patients were randomized to receive ZOL (4 or 8 mg) or placebo every 3 weeks for 9 months, followed with another 12 month in an extension study. SREs and AEs were recorded at each 3-week visit. The analysis was based on the entire 21 months, i.e., the 12 months extension study in addition to the core 9 months study.

No quality of life or cost outcomes were collected during the clinical trial. For the purpose of this analysis, these outcomes were modeled by supplementing the trial data with information from other sources, as described in a subsequent section (see “Quality of Life Inputs”). Specifically, for each patient enrolled in the trial, the following trial information was included: overall survival, occurrence of each type of SRE (pathological vertebral fracture; pathological non-vertebral fracture; spinal cord compression; radiation therapy; hypercalcemia; surgery to bone), and total number of infusions of ZOL (or placebo). On the basis of these data, estimates of the quality-adjusted survival and SRE-related costs were constructed for each individual by assigning to each patient experiencing a specific SRE an increase in costs (corresponding to the estimated cost of managing the SRE) and a reduction in quality of life (i.e., utility), which was then expressed in QALYs. The time spent by each patient without an SRE was assumed to be associated with the estimated utility of an average patient with advanced RCC with bone metastases but without SREs, as explained in detailed in the next sections.

Clinical inputs

As reported in Lipton et al. [10], the median overall survival in these RCC patients showed a trend toward favoring ZOL (295 days for the 4-mg ZOL group versus 216 days for the placebo group) but did not achieve statistical significance compared with placebo (P = 0.179). The average duration of survival was 264.16 days in the placebo group and 330.70 days in the ZOL group. For the purpose of the analysis, the observed survival of the patients was used and, therefore, any difference in (mean) survival between groups was included for analysis.

The number of SREs recorded in each cohort is presented in Table 1. As reported in Lipton et al. [10], the frequency of SREs was statistically significantly less among patients receiving ZOL. Specifically, the percentage of patients who experienced an SRE was reduced significantly for the 4-mg ZOL group (37%) compared with the placebo group (74%; P = 0.015) [10]. The annual incidence of skeletal complications, or skeletal morbidity rate, was reduced from a mean of 3.38 events per year for patients in the placebo group to 2.68 events per year (P = 0.014) for patients who were treated with 4 mg of ZOL [10].

Table 1.

Number of SREs in ZOL and Placebo groups

| ZOL 4 mg (n = 27) | Placebo (n = 19) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of SREs | SRE per person per yeara | Number of SREs | SRE per person per yeara | |

| Pathological vertebral fractures | 1 | 0.041 | 5 | 0.364 |

| Pathological non-vertebral fractures | 3 | 0.123 | 9 | 0.655 |

| Spinal cord compression | 1 | 0.041 | 3 | 0.218 |

| Radiation therapy | 10 | 0.409 | 12 | 0.873 |

| Surgery to the bone | 3 | 0.123 | 4 | 0.291 |

| All SREs | 18 | 0.736 | 33 | 1.349 |

Every counted SRE was followed by 20-day period during which no SRE was counted

No patients experienced hypercalcemia

aSRE/(Average survival in years × number of patients)

Cost inputs

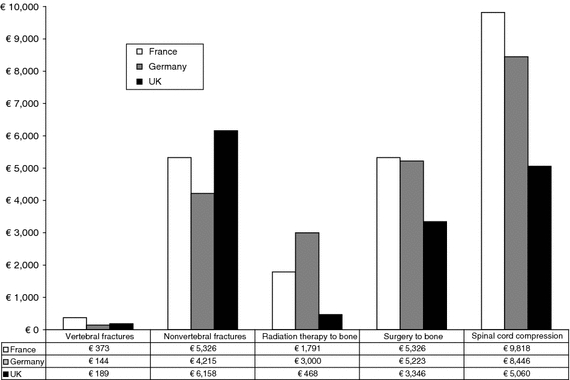

The published literature regarding costs of SREs is limited. In particular, a search did not identify cost estimates for Germany or France. Thus, SRE costs were estimated on the basis of hospital statistics regarding diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) (GHS in France, G-DRG in Germany, and HRG in the UK) (summarized in Table 2 and detailed in the Appendix).

Table 2.

Costs of drug, drug administration, and supplies by country

| France | Germany | UK | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug cost | € 270.00 | € 254.00 | € 218.32 |

| Administration costs | € 18.72 | € 17.80 | € 47.68 |

| Supplies costs | € 3.36 | € 1.72 | € 4.86 |

| Total per infusion | € 292.08 | € 273.53 | € 270.86 |

See Appendix for detail description and sources for drug, administration, and supply cost by country

Given that 34% of vertebral fractures in cancer patients [14] and 33% in the general population [15] are symptomatic and 7% [14] of fractures in cancer patients and approximately 8% in the general population [15] are managed in the hospital, the cost of treating a pathological vertebral fracture was assumed to be only 7% of the DRG costs. For example, in France the DRG cost of a hospitalized vertebral fracture was € 5,326. Therefore, in the model, the cost of vertebral fractures was estimated at only € 373 (€ 5,326 × 7%).

For each patient receiving ZOL therapy, the total cost of infusion was estimated by multiplying the number of infusions received during the trial (9.78 per patient [range: 1–30]) by the estimated cost of an infusion, including drug costs (obtained from price and/or reference lists) (summarized in Table 2 and detailed in the Appendix). The costs of labor, material, and supplies were based on a time and motion study detailing the tasks and resource consumption associated with the use of ZOL [16]. The valuation of the labor and material supplies was based on various sources (Appendix).

Quality of life inputs

Limited information exists regarding the level of utility experienced by patients with advanced stage RCC. A search of Medline identified only one study reporting on the utility of patients with metastatic RCC enrolled in a large, international, randomized Phase III trial of sunitinib (N = 375) compared to interferon alfa (N = 375) as first-line treatment therapy [17]. Health state utilities were measured via the EuroQol Group’s self-reported health status measure (EQ-5D), including the population preference-based health state utility score (EQ-5D Index) and a patient’s overall health state on a visual analog scale (EQ-VAS). Both the EQ-5D Index and the EQ-VAS have been shown to be reliable and valid for assessing health-related quality of life in cancer patients. At baseline, the EQ-5D Index was 0.76 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.23) in both groups. The EQ-VAS was 73.80 mm (SD = 18.50 mm) for sunitinib and 71.43 mm (SD = 19.51 mm) for interferon alfa patients. Thus, for the purpose of the present analysis, the baseline utility of metastatic RCC (without SRE) was assumed to be 0.76.

Consistent with previous economic analyses of bisphosphonates in cancer [11, 18], patients experiencing a SRE were expected to incur a reduction in utility for a period of 1 month. The reduction in quality of life was assumed to vary by type of SRE (Table 3), based on the previous work by Hillner et al. [18]. For example, a patient with spinal cord compression was assumed to experience a reduction in quality of life of 80% from the baseline score of 0.76 for a period of 1 month. The negative impact of vertebral fractures on utility was assumed to occur only among those patients who were symptomatic (34%), as reported in patients with vertebral fractures in another cancer [14] and in the general population [15].

Table 3.

Utilities for patients with and without SREs

| Reduction in Utility due to SRE* | Implied Utility | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (no SRE) | NA | 0.76 |

| Pathological vertebral fractures | 20% in 34% of patients with symptomatic fractures | 0.7083† |

| Pathological non-vertebral fractures | 20% | 0.608 |

| Spinal cord compression | 80% | 0.152 |

| Radiation therapy | 40% | 0.304 |

| Surgery to the bone | 60% | 0.456 |

* Source adapted from Hillner et al. [18]

† i.e., 34% × 0.76 × (1–20%) + (1–34%) × 0.76

Analyses

To estimate the ICUR, the economic analysis first estimates the average total cost of treatment with ZOL (C Z) and placebo (C p) and average QALYs gained for ZOL (E Z) and placebo (E p). Next, the ICUR was calculated with the following formula:

|

1 |

Whether ZOL is cost-effective compared to placebo depends on whether its ICUR exceeds or remains below a generally accepted, societal maximum willingness to pay (WTP) (λ). That is, ZOL was considered cost-effective relative to placebo if:

|

2 |

For instance, a given therapy can be considered cost-effective if its ICUR is ≤€ 30,000 (i.e., λ = € 30,000). If the difference in cost (C Z − C p) is negative and the difference in QALY (E Z − E p) is positive, then ZOL can be considered to be the dominant or preferred option, as it both saves costs and saves QALYs. Univariate sensitivity analyses on individual model parameters (using ranges described in Table 4) were conducted to assess the uncertainty surrounding the estimate of the cost-effectiveness ratio (cost per QALY gained). To facilitate comparisons across various sensitivity analysis scenarios, the ICUR was mathematically re-arranged linearly into a net monetary benefit (NMB) framework [19]. The NMB was calculated as difference in QALYs multiplied by the WTP (λ) minus the difference in cost of therapy. Therefore, with the same parameter definitions, the NMB may be defined by:

|

3 |

If the NMB is greater than zero, then ZOL is cost-effective compared to placebo; if equal to zero, the strategies are equivalent; and less than zero, placebo is more cost-effective given the maximum WTP (λ) for a QALY gained. The greater the magnitude of the NMB, the larger the difference in cost-effectiveness will be.

Table 4.

Summary of model input parameters for sensitivity analyses

| Baseline | Lowa | Higha | Assumed distributiona | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline utilityb | 0.76 | 0.52 | 1.00 | Uniform |

| Reduction in utility due to pathological vertebral fracturesb | 20% | 0% | 40% | Uniform |

| Reduction in utility due to pathological non-vertebral fracturesb | 20% | 0% | 40% | Uniform |

| Reduction in utility due to spinal cord compressionb | 80% | 60% | 100% | Uniform |

| Reduction in utility due to radiation therapyb | 40% | 20% | 60% | Uniform |

| Reduction in utility due to surgery to the boneb | 60% | 40% | 80% | Uniform |

| Proportion of vertebral fractures that are symptomaticb | 34% | 17% | 51% | Uniform |

| Cost SREsc, b | –d | 0.5 × baseline | 1.5 × baseline | Uniform |

| Cost of labor for infusionb | –e | 0.5 × baseline | 1.5 × baseline | Uniform |

| Cost of material supplies for infusionb | –e | 0.5 × baseline | 1.5 × baseline | Uniform |

| Discount rate (France and Germany) | 5% | 0% | 10% | Not applicablef |

| Discount rate (United Kingdom) | 3.5% | 0% | 10% | Not applicablef |

NA not applicable

a For assumed normal distributions, the low and high values represent the 5 and 95% confidence interval limit, respectively; for assumed uniform distributions, the low and high values represent the minimum and maximum value, respectively

b Same assumptions across all countries

c Same assumptions across all SREs

d Actual value varies from country to country (see text and Fig. 2 for details)

e Actual value varies from country to country (see text and Table 2 for details)

f Not included in multivariate sensitivity analysis

Multivariate sensitivity analysis was addressed by a combination of bootstrapping and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA). The uncertainty from the trial data is captured by the bootstrap procedure and the uncertainty from the model is addressed by the PSA. The latter is a form of sensitivity analysis whereby the model parameters are replaced by random draws from the probability distributions that reflect the uncertainty of these parameters. For each combination of random draws, new outcomes are generated. When this process is repeated many (e.g., 1,000) times, one may picture the outcomes as distributions (given 1,000 observations). Bootstrapping is also a type of uncertainty analysis. This means that one simulates a large number of new trials (e.g. 1,000) of the same size by drawing—with replacement—from the original trial. Each new trial leads to new outcomes and as with the PSA, one may describe the results using distributions. Here, both approaches are carried out simultaneously, meaning that each combined random drawn from the PSA is linked to a newly simulated trial. As such, uncertainty from trial results and from model parameters is simultaneously assessed. The results of the joint 1,000 PSA and bootstrap replicates can then be analyzed and described using simple descriptive statistics.

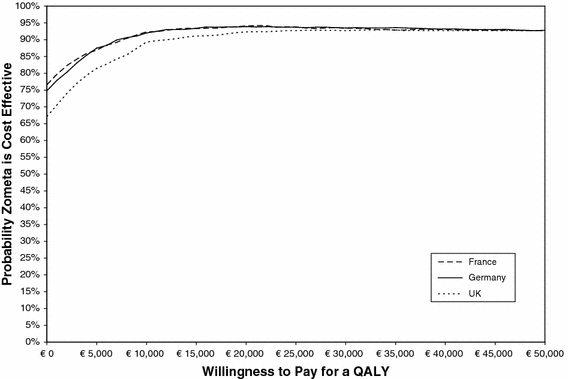

Specifically, one may estimate the proportion of the 1,000 model replications in which ZOL is cost savings or cost-effective at a given λ (e.g., € 30,000). Acceptability curves [20] can be drawn showing the proportion of model replications in which ZOL is cost-effective versus placebo for increasing levels of λ, providing an indication of the level of uncertainty associated with the results. In the present analysis, 1,000 iterations of the model were generated, using a random selection of values according to the parametric uncertainty distributions specified in Table 4.

Following widely used country-specific health technology assessment guidelines, all costs and benefits for economic and clinical outcomes occurring beyond the first year of the analysis were discounted at the rate of 5% per annum in France and Germany, and 3.5% in the UK. All costs were expressed in 2008 prices. For the purpose of comparison across countries, all costs in Great Britain pounds were converted into Euro currency at the rate of £1 = € 1.1196 (as of Dec 12, 2008).

Results

Base case economic results

The use of ZOL was associated with an estimated average of 0.67 SREs per person compared to 1.74 SREs per person in patients receiving placebo, for an average reduction of 1.07 SREs per patient (Table 5). The use of ZOL in France and Germany was associated with an estimated average of 0.6638 discounted QALYs compared to 0.5075 discounted QALYs in patients receiving placebo (Table 5). These figures were slightly different in the UK, owing to the different discounting rate. Therefore, treatment with ZOL improved QALYs by 0.1563 in France and Germany and by 0.1575 in the UK (Table 5).

Table 5.

Base case QALY and costs for ZOL and Placebo groups

| Placebo (N = 19) | ZOL 4 mg (N = 27) | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | |||

| SRE per person | 1.74 | 0.67 | −1.07 |

| Discounted QALY per person | 0.5075 | 0.6638 | 0.1563 |

| Discounted SRE-related costs per person | € 6,414 | € 2,218 | −€ 4,196 |

| Discounted drug costs per person | € 0 | € 2,837 | € 2,837 |

| Discounted total costs per person | € 6,414 | € 5,056 | −€ 1,358 |

| Cost per QALY | −€ 8,689 | ||

| Net monetary benefit | € 6,049 | ||

| Germany | |||

| SRE per person | 1.74 | 0.67 | −1.07 |

| Discounted QALY per person | 0.5075 | 0.6638 | 0.1563 |

| Discounted SRE-related costs per person | € 6,347 | € 2,468 | −€ 3,880 |

| Discounted drug costs per person | € 0 | € 2,657 | € 2,657 |

| Discounted total costs per person | € 6,347 | € 5,125 | −€ 1,223 |

| Cost per QALY | −€ 7,820 | ||

| Net monetary benefit | € 5,913 | ||

| United Kingdom | |||

| SRE per person | 1.74 | 0.67 | −1.07 |

| Discounted QALY per person | 0.5086 | 0.6661 | 0.1575 |

| Discounted SRE-related costs per person | € 4,798 | € 1,443 | −€ 3,355 |

| Discounted drug costs per person | € 0 | € 2,636 | € 2,636 |

| Discounted total costs per person | € 4,798 | € 4,079 | −€ 719 |

| Cost per QALY | −€ 4,566 | ||

| Net monetary benefit | € 5,444 | ||

Compared to placebo, the use of ZOL was associated with a reduction in SRE-related discounted costs (−€ 4,196 in France, −€ 3,880 in Germany, and −€ 3,355 in the UK) (Table 5). With the addition of the drug and administration costs of ZOL (+€ 2,837 in France, +€ 2,657 in Germany, and +€ 2,636 in the UK), the net costs in the ZOL arm (Table 5) were € 1,358, € 1,223, and € 719 less than in the placebo group, in France, Germany, and the UK, respectively.

Overall, the use of ZOL appears to be associated with net savings in QALY and reduction in costs and is therefore superior to placebo Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Costs of SRE by SRE type and country see Appendix for detail description and sources of SRE cost by country

Univariate sensitivity analysis

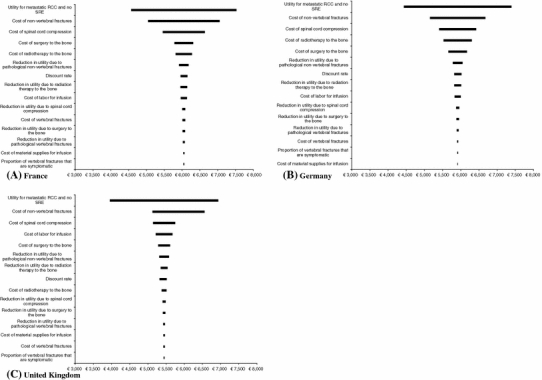

As indicated in Fig. 2, a few of the model inputs (other than the results of the trial itself) individually affect the conclusions of the analysis. Specifically, none of the changes in the individual model parameter resulted in a negative NMB (assuming a willingness to pay of € 30,000 per QALY gained). The most sensitive variables were the assumptions regarding the utility of metastatic RCC without SRE (which is used as the background utility), and the cost of SREs (in particular the costs of non-vertebral fractures and spinal cord compression). Changes in the value of the other parameters typically have less impact on the results.

Fig. 2.

Univariate Sensitivity Analysis around the NMB of Zometa versus Placebo Legend: This figure presents the results of the univariate sensitivity analysis on the NMB (assuming a λ = € 30,000) of ZOL versus placebo using tornado diagrams in the three countries of interest. The model parameters with the largest influence on the NMB (i.e., for which the change in parameter value is associated with the larges change in NMR) is placed at the top of the tornados. Other variables are placed in decreasing order of influence. The vertical lines at the center of the tornadoes represent the point estimates of the NMB (€ 6,049 in France, € 5,913 in Germany, and € 5,444 in the UK). None of the changes in the value of the parameters resulted in the NMB to be less than € 0, implying that none of these changes resulted in the Cost per QALY to be higher than € 30,000 (=λ)

Multivariate sensitivity analysis

The multivariate sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the impact of altering multiple variables simultaneously. This analysis confirmed that ZOL is cost-effective. Figure 3 presents the acceptability curves for the cost-effectiveness of ZOL versus placebo in the three countries. ZOL was cost saving and improved QALY in 67% of the 1,000 multivariate sensitivity analysis simulations in the UK and 77% of the simulations in France (with the proportion for Germany lying in the range). The incremental cost per QALY gained was below € 30,000 in approximately 93–94% of the 1,000 simulations.

Fig. 3.

Acceptability Curve for the Cost-Effectiveness of ZOL Legend: The acceptability curve shows the probability that ZOL is cost-effective compared to placebo, given the results of the 1,000 PSA simulations, across a range of maximum monetary values that decision makers might be willing to pay for a QALY saved (along the “x” axis). For instance, if decision makers are not willing to pay anything for a QALY saved (i.e., they demand that ZOL is cost saving, regardless of the impact on QALYs), then approximately 67% (for the UK) to 77% (for France) of the 1,000 model runs in PSA met this requirement (the acceptability curve crosses the Y axis at the 67% to 77% mark). As the willing to pay for a QALY saved increases, the proportion of 1,000 simulations that meet the decision makers’ criteria also increases, to reach a maximum of 94% for France and Germany around € 22,000 and 93% for the UK around € 34,000

Discussion

The results of the present analysis suggest that the use of ZOL in patients with RCC and bone metastases is highly cost-effective from a government payer perspective in France, Germany, and the UK. ZOL reduced the health care costs associated with SREs by € 3,355 per patient in the UK to € 4,196 per patient in the France (with Germany in between with cost reductions of € 3,880). Even after accounting for the drug and administration costs, ZOL remained cost saving (ranging from € 719–€ 1,358 per patient, depending on the country). Since ZOL is also predicted to improve quality of life due to the reduction in the frequency of SREs and longer survival, ZOL is economically preferred to no therapy (i.e., placebo). These results were found to be robust to variations in input parameter values. In the PSA, the incremental cost per QALY gained was € 30,000 or less in 93–94% of the 1,000 simulations, indicating at the same time that in 6–7% of model iterations ZOL is cost ineffective.

The results also indicate that the cost-effectiveness is relatively comparable across the three countries of interest, despite the differences in costing methodologies and assumptions.

The main strength of this analysis is the direct reliance on the patient-level data regarding SREs and survival to estimate the costs and quality of life impacts of these events and the benefits of therapy with ZOL. The reliance on the patient-level data allows a more comprehensive assessment of the uncertainty around the point estimate of cost-effectiveness than those presented in previous cost-effectiveness analyses of bisphoshonates [18, 21–24].

The analysis includes several important limitations. First, the results are based on a post hoc, retrospective analysis of a very small subgroup of patients with RCC who were taken from a larger pool of patients with bone metastases secondary to solid tumors other than breast or prostate cancer who were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial of ZOL versus placebo. Therefore, the present analysis must be considered exploratory and should be replicated in a larger, pre-planned study designed to formally test the hypothesis that ZOL is effective and cost-effective in a comparable population of RCC patients with bone metastases.

Another important limitation of the analysis is the very small sample size of patients on which it is based. Only 19 placebo and 27 ZOL patients were included, limiting the generalizability and power of the analysis. Nevertheless, this limited evidence was the only peer-reviewed, published [10] information at our disposal regarding the effect of ZOL in RCC patients with bone metastasis. To address the uncertainty associated with this limitation, multivariate sensitivity analysis using a combination of probabilistic sensitivity analysis and bootstrapping was used. The results of these analyses provide some cautious reassurance in that ZOL was cost saving and improved QALY in 67% of the 1,000 multivariate sensitivity analysis simulations in the UK and 77% of the simulations in France (with the proportion for Germany approximately 75%). The incremental cost per QALY gained was below € 30,000 in approximately 93–94% of the 1,000 simulations. In this context, the use of bootstrapping to estimate the level of uncertainty surrounding the estimate of cost-effectiveness is of limited value as the re-sampling is based on the same small number of patients. As such, there is no question again that the results of this analysis should be replicated in a larger group of patients.

Despite the above limitation, it may be important to place the present results pertaining to this small subgroup of RCC patients in the broader context of the effectiveness (and cost-effectiveness) of ZOL in other solid tumors. This agent has been shown to be effective compared to placebo in patients with bone metastases secondary to breast cancer [25], prostate cancer [26], and other solid tumors [9]. Economic studies adopting a European perspective have also shown that ZOL is cost-effective (i.e., cost per QALY < € 30,000) in prostate cancer [12], breast cancer [11], lung cancer [13], and other solid tumors [27]. Thus, even though the sample size upon which this analysis is based is small, its results are consistent with the broader evidence pertaining to ZOL in solid tumors.

The costs and quality-adjusted survival of the patients included in the analysis were not directly observed during the trial. Accordingly, these were estimated on the basis of the observed frequency and types of SREs combined with information collected outside of the trial, such as DRG payments. A key issue is whether the estimates of costs from DRG systems, which are typically assumed to represent averages across many patient groups, apply to RCC cancer patients. For instance, compared to patients without cancer and bone metastases, patients with bone metastases may experience far more complicated recoveries from (long-bone) fractures than other patients, as bone remodeling following a fracture may be severely compromised due to increased osteoclast and reduced osteoblast activity [28]. In addition, the cost estimates used in this analysis may be underestimated because outpatient costs were largely ignored. It is likely that a more protracted recovery from complicated SREs such as non-vertebral fracture or bone surgery will require significant outpatient care. It is likely that the exclusion of outpatient care costs contribute to important underestimations of SRE-related costs.

Likewise, preference scores for the time spent with RCC, with or without SREs, were constructed on the basis of the literature. A search of the Medline-indexed literature identified only one reference that could be used to directly estimate the base case utility of metastatic RCC [17]. As the results of the univariate sensitivity analysis showed, the background utility of patients with RCC and bone metastases (but without concurrent SRE) is an important driver of cost-effectiveness. This is because the utility of time associated with an SRE was estimated using a multiplicative model, in which the background utility level is multiplied by utility decrements adapted from those first initially proposed by Hillner et al. [18]. Therefore, the lower the assumed background utility level, the lower the gain in utility achievable from preventing a given SRE.

The present analysis included the point estimate difference in survival between the placebo and treatment groups in the calculated QALY saved. However, this inclusion of the survival difference may arguably be biased in favor of ZOL since this difference was not statistically significant, as reported in Lipton et al. [10]. More broadly speaking, a debate exists as to whether it is methodologically appropriate to include survival gains in economic analyses when these are not statistically significant [29–33]. However, the question addressed by the economic analysis is much broader: it seeks to understand whether a treatment is cost-effective when considering all costs and benefits—not just survival—and includes the uncertainty surrounding these costs and benefits. Ignoring some of these effects on the basis that they are statistically insignificant does not address whether they are clinically—or more broadly, economically important. For instance, ignoring the difference in survival would have resulted in a reduction in the estimate of QALY gained, from 0.131 to 0.018. However, if survival between placebo and treatment were to be assumed to be identical (i.e., the difference in survival is ignored), then the estimated cost of SREs and drug also must be proportionately modified to reflect the adjusted survival, which determine the level of exposure to the SRE risk and the need for additional infusion with ZOL. Specifically, the SRE and drug costs in the treatment group would have to be reduced (if it is assumed that the treatment group’s survival is exaggerated) or the cost of SRE in the placebo group would have to be increased (if it is assumed that the placebo group’s survival is underestimated). These cost adjustments would likely offset the reduction in QALY gained in the cost-effectiveness ratio. On the other hand, due to the lack of data, the analysis also excluded non-SRE cost, such as the costs of routine or palliative care, incurred by patients in both the placebo and treatment groups. Since patients in the ZOL group were assumed to live longer, it is likely that these patients also incurred higher non-SRE-related care costs. Therefore, instead of arbitrarily omitting possible effects of ZOL and trying to adjust the results to account for this omission, the present analysis included as much of the evidence at our disposal, including the degree of uncertainty surrounding this evidence.

ZOL is the only bisphosphonate specifically approved for the management of SREs in solid tumors other than breast cancer. In addition, no clinical trials have reported on the efficacy of other bisphosphonates for the management of bone metastases in patients with RCC. It would be inappropriate to assume that all bisphosphonates are equally effective. For instance, ZOL has been shown to be more effective than pamidronate for the prevention of SREs in patients with bone metastases subsequent to breast cancer [34]. While ZOL has been shown to be effective in preventing SREs in patients with bone metastases secondary from prostate cancer [35], a trial of pamidronate did not demonstrate comparable effects [36].

The clinical trial upon which the present analysis was based was initiated in early 2000. Since that time, the management of RCC has changed dramatically with the introduction of newer agents such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors [37]. These newer agents are associated with higher response rate, longer (progression-free) survival, and improved quality of life. Thus, it is unclear whether the unique economic value of ZOL therapy as estimated in the present analysis, reflecting the era of interferon therapy, will remain the same in patients treated with the newer agents.

Conclusions

The results of a retrospective subgroup analysis of patients with RCC and bone metastases have demonstrated that significant clinical benefits can be expected from ZOL therapy [10]. The results of the present analysis also suggest that ZOL is likely economically attractive and is predicted to lead to cost savings or to be very cost-effective. These results, based on a post hoc, retrospective analysis of a small sample of RCC patients from a larger trial of solid tumor patients, should be further confirmed in pre-planned analyses of larger, prospective trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the anonymous referees for their very helpful and constructive comments.

Conflict of interest

M. F. Botteman, M. Meijboom, I. Foley and J. M. Stephens received a consulting grant from Novartis Pharma. S. Kaura and Y. M. Chen are employees of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp is the manufacturer of zoledronic acid.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11.

Table 6.

Cost of SREs in France

| SRE | Base | Description/source |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebral fractures | € 373 | Average of DRGs 08M11 Va and 08M11 Wb multiplied by hospitalization rate [14] |

| Non-vertebral fractures | € 5,326 | Average of DRGs 08M11 Va and 08M11 Wb |

| Radiation therapy to bone | € 1,791 | Average of inpatient and outpatient radiation therapy. Inpatient estimate taken from DRG 17K06Zc (€ 2,843.5); Outpatient cost (€ 1,700) taken from Durand-Zaleski [38]; Frequency of inpatient (8%) v. outpatient (92%) radiation taken from Groot et al. [39] |

| Surgery to bone | € 5,326 | Average of DRGs 08M11 Va and 08M11 Wb |

| Spinal cord compression | € 9,818 | DRG 01C05 Wd |

DRG diagnosis-related group

aPathologic fractures and malignant problems of the musculoskeleton and connective tissue without CMA

bPathologic fractures and malignant problems of the musculoskeleton and connective tissue with CMA

cOther radiotherapies and internal-source irradiations

dInterventions on the spine and marrow for neurologic problems with CMA

Table 7.

Cost of SREs in Germany

| SRE | Base | Description/source |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebral fractures | € 144 | DRG I65Ca multiplied by hospitalization rate [14] |

| Non-vertebral fractures | € 4,215 | DRG I13Bb |

| Radiation therapy to bone | € 3,000 | DRG I54Zc |

| Surgery to bone | € 5,223 | Average of DRG I13Ad and DRG I13Bb |

| Spinal cord compression | € 8,446 | DRG B03Xe |

aMalign neoplasia of connective tissue including pathological fracture, age > 16 years, without extremely severe concurrent diseases (€ 2,053.82)

bComplex surgery of the humerus, tibia, fibula or ankle, without several surgeries, without two-sided surgeries, without complex procedure, without complex diagnosis (€ 4,214.70)

cRadiotherapy of diseases or malfunction of the musculo-skeletal system and connective tissue, less than 9 cycles

dComplex surgery of the humerus, tibia, fibula or ankle, with several surgeries, two-sided surgeries, complex procedure or complex diagnosis (€ 6,231.89)

eSurgery of non-acute para-/tetraplegia or surgery of the spine or spinal cord when there exist malign neoplasias or when there exist (extremely) severe concurrent diseases or surgery due to cerebral paralysis, muscular dystrophy, neuropathy with severe concurrent diseases

Table 8.

Cost of SREs in the UK

| SRE | Base | Description/source |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebral fractures | € 189 | Average of HRG code HD36C, HD36B, HD36Aa weighted by the number of treatment in each HRG. NHS National Schedule of Reference Costs 2006–07, £2,405, multiplied by hospitalization rate [14] |

| Non-vertebral fractures | € 6,158 | Average of HRG code HD36C, HD36B, HD36Aa weighted by the number of treatment in each HRG. NHS National Schedule of Reference Costs 2006–07, £2,405, plus the estimated cost of outpatient care for long-bone fractures for 3 months (£5,073) assumed to be incurred by 61% of patients with non-vertebral fractures (total of £5,073 × 61% = £3,095) (based on Ross et al. [24] set of assumptions) |

| Radiation therapy to bone | € 468 |

Average of HRG code SC21Z, SC22Z, SC23Z, SC24Z, SC25Z, SC26Z, SC27Z, SC28Z,b weighted by the number of treatment in each HRG. NHS National Schedule of Reference Costs 2006–07 http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_082571?IdcService=GET_FILE&dID=159075&Rendition=Web Assumes as Ross et al. [24] that 3 sessions take place. Includes the cost of cost of a visit (code 360 Genito-Urinary Medicine contact at £145), the total cost would be £467.53 |

| Surgery to bone | € 3,346 | HRG HD36A–Pathological Fractures or Malignancy of Bone and Connective Tissue with Major CC. NHS National Schedule of Reference Costs 2006–07 |

| Spinal cord compression | € 5,060 | HRG HC25A–Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Disorders with Major CC. NHS National Schedule of Reference Costs 2006–07 |

aHRG Labels: HD36C—Pathological Fractures or Malignancy of Bone and Connective Tissue without CC; HD36B—Pathological Fractures or Malignancy of Bone and Connective Tissue with CC; HD36A—Pathological Fractures or Malignancy of Bone and Connective Tissue with Major CC

bHRG Labels: SC21Z—Deliver a fraction of treatment on a superficial or orthovoltage machine; SC22Z—Deliver a fraction of treatment on a megavoltage machine; SC23Z—Deliver a fraction of complex treatment on a megavoltage machine; SC24Z—Deliver a fraction of radiotherapy on a megavoltage machine using general anesthetic; SC25Z—Deliver a fraction of Total Body Irradiation; SC26Z—Deliver a fraction of intracavitary radiotherapy without general anesthetic; SC27Z—Deliver a fraction of intracavitary radiotherapy with general anesthetic; SC28Z—Deliver a fraction of interstitial radiotherapy

Table 9.

Cost of drug and drug administration in France

| France | Units* | Cost/unit | Sources for cost/unit | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug cost | 1.00 | € 270 | Novartis data on file (IMS price) (Oct 28th 2008) | € 270.00 |

| Labor costs (in minutes) | € 18.72 | |||

| Physician time | 11.12 | € 0.62 | Annual salary 61620.22 per year http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jopdf//jopdf/2008/0329/joe_20080329_0008.pdf | € 6.86 |

| Pharmacy technician time | 10.58 | € 0.21 | http://www.wk-pharma.fr/annonces/static.php?template=grille_salaires.html&deplies=6&selectionnes=6 | € 2.27 |

| Nurse time | 44.25 | € 0.22 | Gross hourly rate of nurse (13 Euros) http://www.syndicatinfirmier.com/article.php3?id_article = 503&var_recherche = heures | € 9.59 |

| Supplies | € 3.36 | |||

| Needle | 2.00 | € 0.19 | 0,5 cc 50U/ml http://www.lavitrinemedicale.com/pages/affProd.asp?idProduit=1478 | € 0.37 |

| Gauze | 2.00 | € 0.02 | Compresses de gaze non-steriles 17 fils, 8 plis. 5 × 7,5 cm http://www.lavitrinemedicale.com/pages/affProd.asp?idProduit=1367 | € 0.04 |

| Alcohol swab | 2.00 | € 0.04 | Tampons alcoolises http://www.lavitrinemedicale.com/pages/affProd.asp?idProduit=1472 | € 0.07 |

| Syringe | 2.00 | € 0.09 | 10 cc Source: http://www.lavitrinemedicale.com/pages/affProd.asp?idProduit=1520 | € 0.18 |

| Set of gloves | 3.00 | € 0.13 | Gants micro-touch hydracare http://www.lavitrinemedicale.com/pages/affProd.asp?idProduit=1247 | € 0.39 |

| Medical tape | 1.00 | € 0.02 | Bandes de gaze 4 m × 5 cm http://www.lavitrinemedicale.com/pages/affProd.asp?idProduit=1345 | € 0.02 |

| Sample tubes | 2.00 | € 0.16 | Tube sous vide en verre venoject terumo 3 ml serum 65 × 10,25 mm http://www.socimed.com/tube-sous-vide-verre-venoject-terumo-serum-1025mm-p-2904.html | € 0.32 |

| Disposable i.v. set | 1.00 | € 1.94 | http://www.socimed.com/catheter-intraveineux-surflo-terumo-p-3087.html | € 1.94 |

| Thermometer cover | 1.00 | € 0.04 | Lubrifiee, les 100; http://www.lavitrinemedicale.com/pages/affProd.asp?idProduit=380 | € 0.04 |

| Grand total | € 292.08 |

* Based on a micro-costing study of DesHarnais-Castel et al. [16]

Table 10.

Cost of drug and drug administration in Germany

| Germany | Units* | Cost/unit | Sources for cost/unit | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug cost | 1.00 | € 254 | Novartis data on file (IMS price) (Oct 28th 2008) | € 254.00 |

| Labor costs (in minutes) | € 17.80 | |||

| Physician time | 11.12 | € 0.42 | General physician salary, International Labour Organization. LABORSTAT. http://laborsta.ilo.org/cgi-bin/brokerv8.exe | € 4.64 |

| Pharmacy technician time | 10.58 | € 0.22 | Auxiliary nurse salary, International Labour Organization. LABORSTAT. http://laborsta.ilo.org/cgi-bin/brokerv8.exe | € 2.28 |

| Nurse time | 44.25 | € 0.25 | Professional nurse salary, International Labour Organization. LABORSTAT. http://laborsta.ilo.org/cgi-bin/brokerv8.exe | € 10.88 |

| Supplies | € 1.72 | |||

| Needle | 2.00 | € 0.03 | Normkanülen http://www.medicotec-shop.de/?p=artdetails&from_page=artliste&Artikel=52354&suchtext=&form_sortBy= | € 0.06 |

| Gauze | 2.00 | € 0.02 | Gazin-Kompressen steril groß, 10 × 10 cm (5 × 2); 56 Pack http://www.megro.de/top/is.top | € 0.03 |

| Alcohol swab | 2.00 | € 0.03 | http://www.dammeyer-selzer.de/sonderangebote/index.htm | € 0.06 |

| Syringe | 2.00 | € 0.17 | BD Plastipak Spezialspritzen 3 ml http://www.megro.de/top/is.top | € 0.33 |

| Set of gloves | 3.00 | € 0.04 | http://www.dammeyer-selzer.de/sonderangebote/index.htm | € 0.13 |

| Medical tape | 1.00 | € 0.04 | WS-Universal-Binde 5 m × 10 cm (binden elastisch) http://www.megro.de/top/is.top | € 0.04 |

| Sample tubes | 2.00 | € 0.02 | Sterican Kanülen (tube) http://www.dammeyer-selzer.de/sonderangebote/index.htm | € 0.03 |

| Disposable i.v. set | 1.00 | € 1.01 | Infusionsleitung PE 150 cm http://www.megro.de/top/is.top | € 1.01 |

| Thermometer cover | 1.00 | € 0.03 | Hygiene-Schutzhüllen http://www.medisales.de/top/is.top | € 0.03 |

| Grand total | € 273.53 |

* Based on a micro-costing study of DesHarnais-Castel et al. [16]

Table 11.

Cost of drug and drug administration in the UK

| UK | Units* | Cost/unit | Sources for cost/unit | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug cost | 1.00 | € 218.32 | British National Formulary, 2008 | € 218.32 |

| Labor costs (in minutes) | € 47.68 | |||

| Physician time | 11.12 | € 2.15 | Unit costs of health and social care 2007 [40] Consultant, Medical, p 179 | € 23.86 |

| Pharmacy technician time | 10.58 | € 0.69 | Unit costs of health and social care 2007 [40] Community Pharmacy p 116 | € 7.30 |

| Nurse time | 44.25 | € 0.37 | Unit costs of health and social care 2007 [40] Nurse, day ward, p 167 | € 16.51 |

| Supplies | € 4.86 | |||

| Needle | 2.00 | € 0.21 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/microlance-needles-16g-15-inch-per-100-p-5113.html | € 0.41 |

| Gauze | 2.00 | € 0.04 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/swabs-gauze-50-50cm-12-ply-bp-type-13-per-pack-of-100-p-3553.html | € 0.08 |

| Alcohol swab | 2.00 | € 0.03 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/swabs-non-woven-sterile-5cm-ply-per-case-of-3000-p-6779.html | € 0.05 |

| Syringe | 2.00 | € 0.12 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/1ml-plastipak-syringes-per-box-of-100-p-5134.html | € 0.25 |

| Set of gloves | 3.00 | € 0.04 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/performer-soft-vinyl-examination-glove-medium-per-1000-p-4808.html | € 0.11 |

| Medical tape | 1.00 | € 0.02 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/white-zinc-oxide-medical-tape-125cm-5m-per-24-rolls-p-8070.html | € 0.02 |

| Sample tubes | 2.00 | € 0.14 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/vacutainer-tube-plain-10ml-per-100-p-7029.html | € 0.29 |

| Disposable i.v. set | 1.00 | € 3.58 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/universal-mediflex-solution-giving-set-p-7073.html | € 3.58 |

| Thermometer cover | 1.00 | € 0.06 | http://www.medisave.co.uk/general-purpose-thermometer-probe-cover-pack-of-20-p-7014.html | € 0.06 |

| Grand total | € 270.86 |

* Based on a micro-costing study of DesHarnais-Castel et al. [16]

References

- 1.Zekri J, Ahmed N, Coleman RE, Hancock BW. The skeletal metastatic complications of renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2001;19:379–382. doi: 10.3892/ijo.19.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer. 1997;80:1588–1594. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1588::AID-CNCR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Depuy V, Anstrom KJ, Castel LD, Schulman KA, Weinfurt KP, Saad F. Effects of skeletal morbidities on longitudinal patient-reported outcomes and survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer. 2007;15:869–876. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinfurt KP, Li Y, Castel LD, Saad F, Timbie JW, Glendenning GA, Schulman KA. The significance of skeletal-related events for the health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2005;16:579–584. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delea TE, McKiernan J, Brandman J, Edelsberg J, Sung J, Raut M, Oster G. Impact of skeletal complications on total medical care costs among patients with bone metastases of lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2006;1:571–576. doi: 10.1097/01243894-200607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delea T, McKiernan J, Brandman J, Edelsberg J, Sung J, Raut M, Oster G. Retrospective study of the effect of skeletal complications on total medical care costs in patients with bone metastases of breast cancer seen in typical clinical practice. J. Support. Oncol. 2006;4:341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aapro, M., Abrahamsson, P.A., Body, J.J., Coleman, R.E., Colomer, R., Costa, L., Crino, L., Dirix, L., Gnant, M., Gralow, J., Hadji, P., Hortobagyi, G.N., Jonat, W., Lipton, A., Monnier, A., Paterson, A.H., Rizzoli, R., Saad, F., Thurlimann, B.: Guidance on the use of bisphosphonates in solid tumours: recommendations of an international expert panel. Ann. Oncol. 19, 420–432 (2008) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian S, Yanagihara R, Hirsh V, Krzakowski M, Pawlicki M, De SP, Zheng M, Urbanowitz G, Reitsma D, Seaman JJ. Zoledronic acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with lung cancer and other solid tumors: a phase III, double-blind, randomized trial–the Zoledronic Acid Lung Cancer and Other Solid Tumors Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:3150–3157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian NS, Yanagihara R, Hirsh V, Krzakowski M, Pawlicki M, De SP, Zheng M, Urbanowitz G, Reitsma D, Seaman J. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma and other solid tumors: a randomized, Phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2613–2621. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipton A, Zheng M, Seaman J. Zoledronic acid delays the onset of skeletal-related events and progression of skeletal disease in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:962–969. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botteman M, Barghout V, Stephens J, Hay J, Brandman J, Aapro M. Cost effectiveness of bisphosphonates in the management of breast cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2006;17:1072–1082. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meijboom, M., Botteman, M., Kaura, S.: Zoledronic acid is cost effective for the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases in France and Germany. Presented at the Annual American Urology Association Meeting, 25–30 April, 2009, Chicago, IL, USA 2009

- 13.Stephens, J., Kaura, S., Botteman, M.F.: Cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid versus placebo in the management of skeletal metastases in lung cancer patients: comparison across 3 European Countries. Presented at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 29–June 2, 2009

- 14.McKean H, Miller RC, Jatoi A. Non-traumatic vertebral fractures in patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer: a previously unreported, unrecognized problem. Dis. Esophagus. 2007;20:102–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross PD, Davis JW, Epstein RS, Wasnich RD. Pain and disability associated with new vertebral fractures and other spinal conditions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1994;47:231–239. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DesHarnais CL, Bajwa K, Markle JP, Timbie JW, Zacker C, Schulman KA. A microcosting analysis of zoledronic acid and pamidronate therapy in patients with metastatic bone disease. Support. Care Cancer. 2001;9:545–551. doi: 10.1007/s005200100249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella D, Li JZ, Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin A, Charbonneau C, Kim ST, Chen I, Motzer RJ. Quality of life in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib or interferon alfa: results from a phase III randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:3763–3769. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillner BE, Weeks JC, Desch CE, Smith TJ. Pamidronate in prevention of bone complications in metastatic breast cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:72–79. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stinnett AA, Mullahy J. Net health benefits: a new framework for the analysis of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Med. Decis. Making. 1998;18:S68–S80. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9801800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Hout BA, Al MJ, Gordon GS, Rutten FF. Costs, effects and C/E-ratios alongside a clinical trial. Health Econ. 1994;3:309–319. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dranitsaris G, Hsu T. Cost utility analysis of prophylactic pamidronate for the prevention of skeletal related events in patients with advanced breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer. 1999;7:271–279. doi: 10.1007/s005200050260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberato NL, Marchetti M, Tamburlini A. Pamidronate in advanced breast cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis [abstract] Eur. J. Cancer. 2000;36:S4. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De CE, Hutton J, Canney P, Body JJ, Barrett-Lee P, Neary MP, Lewis G. Cost-effectiveness of oral ibandronate compared with intravenous (i.v.) zoledronic acid or i.v. generic pamidronate in breast cancer patients with metastatic bone disease undergoing i.v. chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer. 2006;13:975–986. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0828-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross JR, Saunders Y, Edmonds PM, Patel S, Wonderling D, Normand C, Broadley K. A systematic review of the role of bisphosphonates in metastatic disease. Health Technol. Assess. 2004;8:1–176. doi: 10.3310/hta8040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H, Nakamura S, Asaga T, Iino Y, Watanabe T, Goessl C, Ohashi Y, Takashima S. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:3314–3321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, Tchekmedyian S, Venner P, Lacombe L, Chin JL, Vinholes JJ, Goas JA, Zheng M. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:879–882. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marfatia, A.A., Botteman, M., Foley, I., Brandman, J., Langer, C.: Economic value of Zoledronic Acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with solid tumors: the case of the United Kingdom (UK). Presented at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2007

- 28.Mastro AM, Gay CV, Welch DR, Donahue HJ, Jewell J, Mercer R, DiGirolamo D, Chislock EM, Guttridge K. Breast cancer cells induce osteoblast apoptosis: a possible contributor to bone degradation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004;91:265–276. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trippoli S, Messori A. Cost-effectiveness analyses of statistically ineffective treatments. JAMA. 1998;280:1992–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.1992-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobson MW. Cost effectiveness of coronary bypass surgery versus angioplasty. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:1840–1841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706193362519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hlatky, M.A.: Reply to Jacobson, M.W.: Cost effectiveness of coronary bypass surgery versus angioplasty. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 1840–1841 (1997) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Trippoli S, Vaiani M, Messori A, Tendi E. Survival gain in cost-effectiveness studies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:3318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillner, B.E.: Reply to Trippoli et al. 2000. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 3318 (2000)

- 34.Rosen LS, Gordon D, Kaminski M, Howell A, Belch A, Mackey J, Apffelstaedt J, Hussein MA, Coleman RE, Reitsma DJ, Chen BL, Seaman JJ. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid compared with pamidronate disodium in the treatment of skeletal complications in patients with advanced multiple myeloma or breast carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, comparative trial. Cancer. 2003;98:1735–1744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, Tchekmedyian S, Venner P, Lacombe L, Chin JL, Vinholes JJ, Goas JA, Chen B. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1458–1468. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Small EJ, Smith MR, Seaman JJ, Petrone S, Kowalski MO. Combined analysis of two multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled studies of pamidronate disodium for the palliation of bone pain in men with metastatic prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:4277–4284. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Kim ST, Chen I, Bycott PW, Baum CM, Figlin RA. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durand-Zaleski I. Economic evaluation of radiotherapy: methods and results. Cancer Radiother. 2005;9:449–451. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groot MT, Boeken Kruger CG, Pelger RC, Uyl-de Groot CA. Costs of prostate cancer, metastatic to the bone, in the Netherlands. Eur. Urol. 2003;43:226–232. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2007. Personal Social Services Research Unit. Canterbury: University of Kent; 2007. [Google Scholar]